NOBODY WANTS TO HAVE a chronic long-term illness. Unfortunately, most of us will experience two or more of these conditions during our lives. This book has been written to help people with chronic illness explore healthy ways to live with a physical or mental condition. This may seem like a strange concept. How can you have an illness and live a healthy life? To answer this, we need to look at what happens with most chronic health problems. These diseases, be they heart disease, diabetes, depression, liver disease, bipolar disorder, emphysema, or any one of a host of others, cause most people to experience fatigue as well as to lose physical strength and endurance. In addition, they may cause emotional distress, such as frustration, anger, anxiety, or a sense of helplessness. Health is soundness of body and mind, and a healthy life is one that seeks that soundness. Therefore, a healthy way to live with a chronic illness is to work at overcoming the physical, mental, and emotional problems caused by the condition. The challenge is to learn how to function at your best regardless of the difficulties life presents. The goal is to achieve the things you want to do and to get pleasure from life. That is what this book is all about.

Before we go any further, let’s talk about how to use this book. Throughout this book you will find information to help you learn and practice self-management skills. This is not a textbook; you might think of it as a workbook. You do not need to read every word in every chapter. Instead, read the first two chapters and then use the table of contents to find the information you need. Feel free to skip around and to take notes right in the book. This will help you learn the skills you need in order to follow your individual path.

You will not find any miracles or cures in these pages. Rather, you will find hundreds of tips and ideas to make your life easier. This advice comes from physicians and other health professionals, as well as people like you who have learned to positively manage their chronic health problems. Please note that we said “positively manage.” There is no way to avoid managing a chronic condition. If you choose to do nothing, that is one way of managing. If you only take medication, that is another management style. If you choose to be a positive self-manager and undergo all the best treatments that health care professionals have to offer, and to be proactive in your own day-to-day management, you will live a healthier life.

In this chapter we discuss chronic illness in general as well as point out the most common problems. In addition, we give some guidance on the self-management skills that are unique to particular conditions. You will soon see that the problems and skills have much more in common than you might think, no matter what the health problem may be. This is good news in that most people have more than one chronic condition. Therefore, learning the common life skills allows you to successfully manage your life, not just a single condition. The rest of the book gives you the tools needed to become a great manager of both your chronic conditions and all the other aspects of your life.

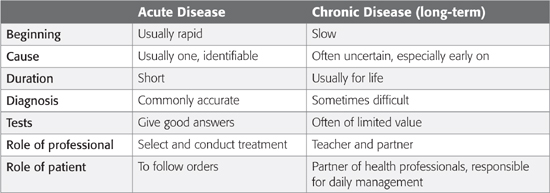

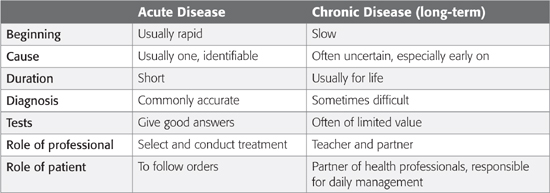

Health problems can be characterized as either “acute” or “chronic.” Acute health problems usually begin suddenly, have a single cause, are often easily diagnosed, last a short time, and get better with medication, surgery, rest, and time. Most people with acute illnesses are cured and return to normal health. There is usually relatively little uncertainty for the patient or the doctor; both usually know what to expect. The illness typically follows a cycle of getting worse for a while, carefully treating or observing the symptoms, and then getting better. Finally, the care of acute illness depends on the body’s ability to heal itself and sometimes on a health professional’s knowledge and experience in finding and administering the correct treatment.

Appendicitis is an example of an acute illness. It typically begins rapidly, signaled by nausea and pain in the abdomen. The diagnosis of appendicitis, once established by examination, leads to surgery for removal of the inflamed appendix. There follows a period of recovery and then a return to normal health.

Table 1.1 Differences Between Acute and Chronic Disease

Chronic illnesses are different (see Table 1.1). They usually begin slowly and proceed slowly. For example, a person may slowly develop blockage of the arteries over decades and then might have a heart attack or a stroke. Arthritis generally starts with brief annoying twinges that gradually increase. Unlike acute disease, chronic illnesses usually have multiple causes that vary over time. These causes may include heredity, lifestyle (smoking, lack of exercise, poor diet, stress, and so on), and exposure to environmental factors such as secondhand smoke or air pollution and to physiological factors such as low levels of thyroid hormone or changes in brain chemistry that may cause depression.

The combination of many causes and unknown factors can be frustrating for those of us who want quick answers. It is difficult for both the doctor and the patient when clear answers aren’t available. In some cases, even when diagnosis is rapid, as in the case of a stroke or heart attack, the long-term effects may be hard to predict. The lack of a regular or predictable pattern is a major characteristic of most chronic illnesses.

Unlike acute disease, where full recovery is expected, chronic illness usually leads to more symptoms and loss of physical or mental functioning. With chronic illness many people assume that the symptoms they are experiencing are due to the disease itself. While the disease can certainly cause pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, and the like, it is not the only cause. Each of these symptoms can contribute to the other symptoms. What’s more, the symptoms can feed on each other. For example, depression causes fatigue, pain causes physical limitations, and these can lead poor sleep and more fatigue. The interactions of these symptoms make the condition worse. It becomes a vicious cycle that only gets worse unless we find a way to break the cycle (see Figure 1.1 on the next page).

Throughout this book we examine ways of breaking the cycle and getting away from the problems of physical and emotional helplessness.

Figure 1.1 The Vicious Cycle of Symptoms

To answer this question, we need to understand how the body operates. As you know, cells are the building blocks of tissues and organs: the heart, lungs, brain, blood, blood vessels, bones, and muscles—in fact, everything in the body. For a cell to remain alive and function normally, three things must happen: it must be nourished, receive oxygen, and get rid of waste products. If anything goes wrong with any of these three functions, the cell becomes diseased. If cells are diseased, the organ or tissue suffers. If this happens you may experience limitations in your ability to be active in daily life. The differences among chronic diseases depend on which cells and organs are affected and the processes by which the disruption occurs. For example, during a stroke, a blood vessel in the brain becomes blocked or bursts. Oxygen and nutrition are cut off for part of the brain supplied by that artery. As a result, the part of your body controlled by the damaged brain cells, such an arm, a leg, or a portion of your face, loses function.

If you have heart disease, heart attacks occur when the vessels supplying blood to the heart muscle become blocked. This is called a coronary thrombosis. When this happens, oxygen is cut off, the heart muscle is injured, and pain results. After the injury the heart may be less effective in supplying the rest of your body with oxygen-carrying blood. Because the heart is pumping blood less efficiently through the body, fluid accumulates in tissues, and you may experience shortness of breath and fatigue.

With diseases of the lungs, either there is a problem getting oxygen to the lungs, as with bronchitis or asthma, or the lungs cannot effectively transfer oxygen to the blood, as with emphysema. In both cases the body is deprived of oxygen.

In diabetes, the pancreas does not produce enough insulin or produces insulin that cannot be used efficiently by the body. Without this insulin the body’s cells are not able to use the glucose (sugar) in the blood for energy.

In liver and kidney disease, the cells of these organs do not work properly, making it difficult for the body to get rid of waste products.

The basic consequences of these diseases are similar: loss of function due to a reduction in oxygen, accumulation of waste products, or inability of the body to use glucose for energy.

Loss of function also occurs in arthritis, but for other reasons. In osteoarthritis, cartilage (the cushioning material found on the ends of bones and as the “disks” between the vertebrae of the back) becomes worn, frayed, or displaced, causing pain. We often do not know exactly why the cartilage cells begin to weaken or die. But the results are pain and disability.

Most mental illnesses are caused by imbalances in chemicals and structural changes in the brain. Too much or too little of these chemical neurotransmitters can affect our moods, thoughts, and behaviors. Treatment of such conditions as depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia often includes restoring chemical balance with medications as well as changes in the environment or self-care practices to support effective coping.

Because chronic illness starts with a malfunction at the cellular level, we may not notice the disease until it intrudes in our life by causing symptoms or declares itself through an abnormal test result.

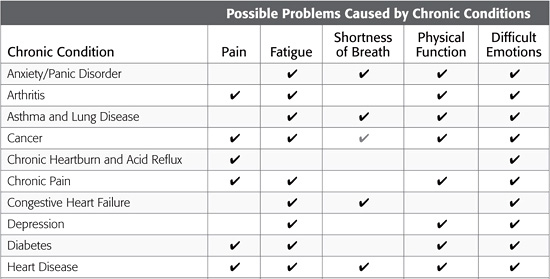

Although the biological causes of chronic illnesses differ, the problems they cause for people are similar. For example, most people with chronic conditions suffer fatigue and loss of energy. Sleeping problems are common. In one case there is pain, while in another case there is trouble breathing. Disability, to some extent, is a part of chronic disease. It may be the inability to use your hands well because of arthritis or stroke or difficulty in walking due to shortness of breath, stroke, arthritis, or diabetes. Sometimes disability is caused by a lack of energy, extreme fatigue, or change in mood.

Depression can be both the reflection of a chronic or recurrent imbalance in brain chemicals and “feeling down” or “feeling blue” that results from having other chronic illnesses. It is hard to maintain a cheerful disposition when your condition causes annoying problems that are unlikely to go away. Along with the depression come fear and concern for the future. Will I be able to remain independent? If I can’t care for myself, who will care for me? Will I get worse? How bad will it get? Both disability and depression may bring loss of self-esteem.

Because there are similarities among chronic illnesses, the essential management tasks and skills you need to learn in order to live with different chronic illnesses are also similar.

Perhaps the most important skill of all is learning to respond to your illness on an ongoing basis to solve day-to-day problems. After all, you live with your condition 24 hours a day; your health care provider sees you only a tiny portion of this time. This means that you must manage your condition. Table 1.2 on page 7 illustrates some of the self-management problems caused by chronic conditions.

From this brief introduction you can see that chronic illnesses have more in common than first meets the eye. In this book we talk about managing these illnesses. For most of the book, however, we will talk more about the management tasks common across many illnesses. If you have more than one health problem, you need not be confused about how to start. The approaches that work for heart disease will also help with lung disease, arthritis, depression, or a stroke. Start with the problem or condition that bothers you most. Table 1.3 on pages 8 and 9 outlines some of the management skills that may be needed to deal with disease-specific problems. Some of these skills are also discussed later in the book in the chapters dealing with specific diseases.

Table 1.2 Self-Management Problems for Common Chronic Conditions

Arthur suffers from severe arthritis. He is in pain most of the time and can’t sleep. He took early retirement because of his arthritis and now, at age 55, he spends his days sitting at home bored. He avoids most physical activity because of the pain, weakness, and shortness of breath. He has become very irritable. Most people, including his family, don’t enjoy his company. It even seems too much trouble when the grandchildren he adores come to visit.

Isabel, age 66, also suffers from severe arthritis. Every day she manages to walk several blocks to the local library or the park. When the pain is severe, she practices relaxation techniques and tries to distract herself. She works several hours a week as a volunteer at a local hospital. She also loves going to see her young grandchildren and even manages to take care of them for a while when her daughter has to run errands. Her husband is amazed at how much zest she has for life.

Arthur and Isabel both live with the same condition with similar physical problems. Yet their abilities to function and enjoy life are very different. Why? The difference lies largely in their attitudes toward the disease and their lives. Arthur has allowed his life and physical capacities to wither. Isabel has learned to take an active role in managing her chronic illness. Even though she has limitations, she controls her life instead of letting the illness control it.

Attitude cannot cure chronic illness. But a positive attitude and certain self-management skills can make it much easier to live with. Much research now shows that the experience of pain, discomfort, and disability can be modified by circumstances, beliefs, mood, and the attention we pay to symptoms. For example, with arthritis of the knee, a person’s degree of depression has been found to be a better predictor of how disabled, limited, and uncomfortable the person will be than the evidence of physical damage to the knee on X-rays. What goes on in a person’s mind is at least as important as what is going on in the person’s body.

In other words, why is it that two people with similar chronic conditions can function in their lives so differently? One may be able to minimize the effect of symptoms, while the other is extremely disabled. One may focus on healthy living, while the other is completely concentrated on the disease. One of the keys in shaping the impact of any disease is how effective and engaged the person is in self-management.

Table 1.3 Management Skills for Dealing with Chronic Conditions

The first responsibility of any chronic condition self-manager is to understand the disease. This means more than learning about what causes the illness, what symptoms it may cause, and what you can do. It also means observing how the disease and its treatment affect you. An illness is different for each person, and with experience you and your family will become experts at determining the effects of the disease and its treatment. In fact, you are the only person who lives with your health problem every minute of every day. Therefore, observing how it affects you and making accurate reports to your health care providers are essential parts of being a good manager. Most chronic illnesses go up and down in intensity. They do not follow a steady path. Let’s look at an example.

John, Sandra, and Mary all have a blood pressure of 160/100, which is too high.

Mary tells her doctor that she sometimes forgets her medications and is not getting much exercise. She is also overweight. Her doctor talks with her, and together they work out a plan to help her remember her medications, to start an exercise program, and to cut down on the amount of food she eats.

John says he is taking his medications, exercising, and eating well. The doctor decides to change his medications, as what he is currently taking is probably not working.

Sandra does not want to take medication. She is doing everything she can to lower her blood pressure: eating well, losing weight, and exercising. Unfortunately, though her blood pressure has improved a bit, it is not good enough. The doctor talks to her about the dangers of high blood pressure and advises starting a medication. In the end Sandra decides that this might be best.

The successful management of high blood pressure varied for each of these patients but depended on each one’s communicating his or her unique situation, experiences, and preferences to the doctor. In other words, effective control of the illness involved an observant patient communicating openly with the health care provider.

When you develop a chronic illness, you become more aware of your body. Minor symptoms that were ignored may now cause concerns. For example, is this chest pain a signal of a heart attack? Is this pain in my knee a sign that the arthritis has gotten worse? There are no simple reassuring answers. Nor is there a fail-safe way of sorting out serious signals from minor temporary symptoms that can be ignored.

It is helpful to know and understand the natural rhythms of your chronic illness. In general, symptoms should be checked out with your doctor if they are unusual, severe, or persistent or if they occur after starting a new medication or treatment plan.

Throughout this book we give some specific examples of what actions to take if you experience certain symptoms. But this is where your partnership with your health care provider becomes critical. Self-management does not mean going it alone. Get help or advice when you are concerned or uncertain.

From what has just been said, self-management may seem like a simple enough concept. Both at home and in the business world, managers direct the show. They don’t do everything themselves; they work with others, including consultants, to get the job done. What makes them managers is that they are responsible for making decisions and making sure that their decisions are carried out.

As the manager of your illness, your job is much the same. You gather information and hire a consultant or team of consultants consisting of your physician and other health professionals. Once they have given you their best advice, it is up to you to follow through. All chronic illnesses need day-to-day management. We have all noticed that some people with severe physical problems get on well while others with lesser problems seem to give up on life. The difference often lies in their management style.

Managing a chronic illness, like managing a family or a business, is a complex undertaking. There are many twists, turns, and midcourse corrections. By learning self-management skills, you can ease the problems of living with your condition.

The key to success in any undertaking is, first, deciding what you want to do; second, deciding how you are going to do it; and, finally, learning a set of skills and practicing them until they have been mastered. Success in chronic disease self-management is the same. In fact, mastering such skills is one of the most important tasks of life.

We will describe hundreds of skills and tools to help relieve the problems caused by chronic illness. We do not expect you to use all of them. Pick and choose. Experiment. Set your own goals. What you do may not be as important as the sense of confidence and control that comes from successfully doing something you want to do. We have learned that knowing the skills is not enough. We need a way of incorporating these skills into our daily lives. Whenever we try a new skill, the first attempts may be clumsy, slow, and show few results. It is easier to return to old ways than to continue trying to master new and sometimes difficult tasks. The best way to master new skills is through practice and evaluation of the results.

What you do about something is largely determined by how you think about it. For example, if you think that having a chronic illness is like falling into a deep pit, you may have a hard time motivating yourself to crawl out, or you may even think the task is impossible. The thoughts you have can greatly determine what happens to you and how you handle your health problems.

Some of the most successful self-managers are people who think of their illness as a path. This path, like any path, goes up and down. Sometimes it is flat and smooth. At other times the way is rough. To negotiate this path one has to use many strategies. Sometimes you can go fast; other times you must slow down. There are obstacles to negotiate.

Good self-managers are people who have learned three types of skills to negotiate this path:

Skills needed to deal with the illness. Any illness requires that you do new things. These may include taking medicine, using an inhaler, or using oxygen. It means more frequent interactions with your doctor and the health care system. Sometimes there are new exercises or a new diet. Even diseases such as cancer require self-management. Chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery can all be made easier through good day-to-day self-management. All of these constitute the work you must do just to manage your illness.

Skills needed to deal with the illness. Any illness requires that you do new things. These may include taking medicine, using an inhaler, or using oxygen. It means more frequent interactions with your doctor and the health care system. Sometimes there are new exercises or a new diet. Even diseases such as cancer require self-management. Chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery can all be made easier through good day-to-day self-management. All of these constitute the work you must do just to manage your illness.

Skills needed to continue your normal life. Just because you have a chronic illness does not mean that life does not go on. There are still chores to do, friendships to maintain, jobs to perform, and family relationships to continue. Things that you once took for granted can become much more complicated in the face of chronic illness. You may need to learn new skills or adapt the way you do things in order to maintain the things you need and want to do.

Skills needed to continue your normal life. Just because you have a chronic illness does not mean that life does not go on. There are still chores to do, friendships to maintain, jobs to perform, and family relationships to continue. Things that you once took for granted can become much more complicated in the face of chronic illness. You may need to learn new skills or adapt the way you do things in order to maintain the things you need and want to do.

Skills needed to deal with emotions. When you are diagnosed as having a chronic illness, your future changes, and with this come changes in plans and changes in emotions. Many of the new emotions are negative. They may include anger (“Why me? It’s not fair”), fear (“I am afraid of becoming dependent on others”), depression (“I can’t do anything anymore, so what’s the use?”), frustration (“No matter what I do, it doesn’t make any difference. I can’t do what I want to do”), or isolation (“No one understands, no one wants to be around someone who is sick”). Negotiating the path of chronic illness, then, also means learning skills to work with these negative emotions. We will teach you some skills to manage these emotions.

Skills needed to deal with emotions. When you are diagnosed as having a chronic illness, your future changes, and with this come changes in plans and changes in emotions. Many of the new emotions are negative. They may include anger (“Why me? It’s not fair”), fear (“I am afraid of becoming dependent on others”), depression (“I can’t do anything anymore, so what’s the use?”), frustration (“No matter what I do, it doesn’t make any difference. I can’t do what I want to do”), or isolation (“No one understands, no one wants to be around someone who is sick”). Negotiating the path of chronic illness, then, also means learning skills to work with these negative emotions. We will teach you some skills to manage these emotions.

With this as background, you can think of self-management as the use of skills to manage the work of living with your illness, continuing your daily activities, and dealing with emotions brought about by chronic illness.

You are not to blame. Chronic diseases are caused by a combination of genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors. For example, stress alone does not cause most chronic illnesses. Mind matters, but mind cannot always triumph over matter. If you fail to recover, it is not because of lack of right mental attitude. There are many things you can control that will help you cope with chronic illness. Remember, you are not responsible for causing the disease or failing to cure it, but you are responsible for taking action to manage your illness.

You are not to blame. Chronic diseases are caused by a combination of genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors. For example, stress alone does not cause most chronic illnesses. Mind matters, but mind cannot always triumph over matter. If you fail to recover, it is not because of lack of right mental attitude. There are many things you can control that will help you cope with chronic illness. Remember, you are not responsible for causing the disease or failing to cure it, but you are responsible for taking action to manage your illness.

Don’t do it alone. One of the side effects of chronic illness is a feeling of isolation. As supportive as friends and family members may be, they often cannot understand what you are experiencing as you struggle to cope with a chronic illness. Chances are, however, that there are others who know firsthand what it is like to live with a chronic condition just like yours. Connecting with other people with similar conditions can reduce your sense of isolation, help you understand what to expect based on a fellow patient’s perspective, offer practical tips on how to manage symptoms and feelings on a day-to-day basis, give you the opportunity to help others cope with their illness, help you appreciate your strengths and realize that things could be worse, and inspire you to take a more active role in managing your illness by seeing others coping successfully. Support can come from reading a book or a newsletter about how someone lives with a chronic illness. Or it can come from talking with others on the telephone, in support groups, or even linking online through computer and electronic support groups.

Don’t do it alone. One of the side effects of chronic illness is a feeling of isolation. As supportive as friends and family members may be, they often cannot understand what you are experiencing as you struggle to cope with a chronic illness. Chances are, however, that there are others who know firsthand what it is like to live with a chronic condition just like yours. Connecting with other people with similar conditions can reduce your sense of isolation, help you understand what to expect based on a fellow patient’s perspective, offer practical tips on how to manage symptoms and feelings on a day-to-day basis, give you the opportunity to help others cope with their illness, help you appreciate your strengths and realize that things could be worse, and inspire you to take a more active role in managing your illness by seeing others coping successfully. Support can come from reading a book or a newsletter about how someone lives with a chronic illness. Or it can come from talking with others on the telephone, in support groups, or even linking online through computer and electronic support groups.

You’re more than your disease. When you have a chronic disease, too often the center of attention becomes your disease. But you are more than your disease—more than a “heart patient” or “lung patient.” And life is more than trips to the doctor and managing symptoms. It is essential to cultivate areas of your life that you enjoy. Small daily pleasures can help balance the other parts in which you have to manage uncomfortable symptoms or emotions. Find ways to enjoy nature by growing a plant or watching a sunset, or indulge in the pleasure of human touch or a tasty meal, or celebrate companionship with family or friends. Finding ways to introduce moments of pleasure is vital to chronic disease self-management. Focus on your abilities and strengths rather than disabilities and problems. Helping others is one way to increase your own sense of what you can do instead of focusing on what you can’t. Celebrate small improvements. If chronic illness teaches anything, it is to live each moment more fully. Within the true limits of whatever disease you have, there are ways to enhance your function, sense of control, and enjoyment of life.

You’re more than your disease. When you have a chronic disease, too often the center of attention becomes your disease. But you are more than your disease—more than a “heart patient” or “lung patient.” And life is more than trips to the doctor and managing symptoms. It is essential to cultivate areas of your life that you enjoy. Small daily pleasures can help balance the other parts in which you have to manage uncomfortable symptoms or emotions. Find ways to enjoy nature by growing a plant or watching a sunset, or indulge in the pleasure of human touch or a tasty meal, or celebrate companionship with family or friends. Finding ways to introduce moments of pleasure is vital to chronic disease self-management. Focus on your abilities and strengths rather than disabilities and problems. Helping others is one way to increase your own sense of what you can do instead of focusing on what you can’t. Celebrate small improvements. If chronic illness teaches anything, it is to live each moment more fully. Within the true limits of whatever disease you have, there are ways to enhance your function, sense of control, and enjoyment of life.

Illness can be an opportunity. Illness, even with its pain and disability, can enrich our lives. It can make us reevaluate what is really important, shift priorities, and move in exciting new directions that we may never have considered before.

Illness can be an opportunity. Illness, even with its pain and disability, can enrich our lives. It can make us reevaluate what is really important, shift priorities, and move in exciting new directions that we may never have considered before.

Jill has breast cancer. Since her diagnosis, she lives more fully than ever: “I was a housewife, lost and aimless after my children grew up and left home. One of the first things I did after the diagnosis was go and teach myself to swim with my head in the water. I had always kept it above, too scared to put my whole self in. That had been the story of my life. Now I do whatever I want. I don’t think about how much time there is, just what I want to do with mine. Surprisingly, I feel less afraid of living.”

A heart attack sometimes makes people decide to slow down. They would rather have more time to deepen relationships with family and friends. A chronic disease that restricts movement may lead some to think again about unused intellectual talents. Meg learned a new language and found an overseas pen pal; Fred dared write the novel he always thought he was “too stupid” to write. Though chronic illness may close some doors, you can choose to open new ones.

Cousins, Norman. Anatomy of an Illness as Perceived by the Patient. New York: Norton, 2005.

Gruman, Jessie. AfterShock. What to Do When the Doctor Gives You—or Someone You Love—a Devastating Diagnosis. New York: Walker, 2010. See also Gruman’s Web site, which offers a selection of further resources: http://www.aftershockbook.com/

Selak, Joy H., and Steven M. Overman. You Don’t Look Sick: Living Well with Invisible Chronic Illness. Binghamton, N.Y.: Haworth Medical Press, 2005.

Sobel, David, and Robert Ornstein. The Healthy Mind, Healthy Body Handbook. Los Altos, Calif.: DRX, 1996.

Sobel, David, and Robert Ornstein. Healthy Pleasures, 2nd ed. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1997.

Sobel, David, and Robert Ornstein. Mind and Body Health Handbook: How to Use Your Mind and Body to Relieve Stress, Overcome Illness, and Enjoy Healthy Pleasures, 2nd ed. Los Altos, Calif.: DRX, 1998.

Weil, Andrew. Healthy Aging: A Lifelong Guide to Your Physical and Spiritual Well-Being. New York: Knopf, 2005.