IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO HAVE a chronic condition without being a self-manager. Some people manage by withdrawing from life. They stay in bed or socialize less. The disease becomes the center of their existence. Other people with the same condition and symptoms somehow manage to get on with life. They may have to change some of the things they do or the way that things get done. Nevertheless, life continues to be full and active. The difference between these two extremes is not the illness but rather how the person with a chronic condition decides to manage the illness. Please note the word decides. Self-management is always a decision: a decision to be active or a decision to do nothing, a decision to seek help or a decision to suffer in silence. This book will help you with these decisions.

Like any skill, active self-management must be learned and practiced. This chapter will start you on your way by presenting the three most important self-management tools: problem solving, decision making, and action planning. Remember: you are the manager. Like the manager of an organization or a household, you must do all of the following things:

1. Decide what you want to accomplish.

2. Look for various ways to accomplish this goal.

3. Draft a short-term action plan or agreement with yourself.

4. Carry out your action plan.

5. Check the results.

6. Make changes as needed.

7. Reward yourself for your success.

Problems sometimes start with a general uneasiness. Let’s say you are unhappy but not sure why. Upon closer examination, you find that you miss contact with some relatives who live far away. With the problem identified, you decide to take a trip to visit these relatives. You know what you want to accomplish, but now you need to make a list of ways to solve the problem.

In the past you have always driven, but you now find driving tiring, so you seek other ways of travel. You consider leaving at noon instead of early in the morning and making the trip in two days instead of one. You consider asking a friend along to share the driving. There is also a train that stops within 20 miles of your destination, or you might fly. You decide to take the train.

The trip still seems overwhelming, as there is so much to do to prepare. You decide to write down all the steps necessary to make the trip a reality. These include finding a good time to go, buying a ticket, figuring out how to handle luggage, seeing if you can make it up and down the stairs to get on the train, wondering if you can walk on a moving train to get food or go to the bathroom, and figuring out how you will get to the station. Each of these steps can be an action plan.

To start making your action plan, you promise yourself that this week you will call and find out just how much the railroad can help. You also decide to start taking a short walk each day, including walking up and down a few steps so that you will be steadier on your feet. You then carry out your action plan by calling the railroad and starting your walking program.

A week later you check the results. Looking back at all the steps to be accomplished, you see that a single call answered many questions. The railroad can help people who have mobility problems and has ways of dealing with many of your concerns. However, you are still worried about walking. Even though you are walking better, you are still unsteady. You make a change in your plan by asking a physical therapist about this, and he suggests using a cane or walking stick. Although you don’t like using it, you realize that a cane will give you the extra security needed on a moving train.

You have just engaged in problem solving to achieve your goal to take a trip. Now let’s review the specific steps in problem solving.

1. Identify the problem. This is the first and most important step in problem solving—and usually the most difficult step as well. You may know, for example, that stairs are a problem, but it will take a little more effort to determine that the real problem is fear of falling.

2. List ideas to solve the problem. You may be able to come up with a good list yourself, but you may sometimes want to call on your consultants. These can be friends, family, members of your health care team, or community resources. One note about using consultants: these folks cannot help you if you do not describe the problem well. For example, there is a big difference between saying that you can’t walk because your feet hurt and saying that your feet hurt because you cannot find walking shoes that fit properly.

3. Pick an idea to try. As you try something new, remember that new activities are usually difficult. Be sure to give your potential solution a fair chance before deciding it won’t work.

4. Check the results after you’ve given your idea a fair trial. If all goes well, your problem will be solved.

5. If you still have the problem, pick another idea from your list and try again.

6. Use other resources (your consultants) for more ideas if you still do not have a solution.

7. Finally, if you have gone through all of the steps until all ideas have been exhausted and the problem is still unsolved, you may have to accept that your problem may not be solvable right now. This is sometimes hard to do. The fact that a problem can’t be solved right now doesn’t mean that it won’t be solvable later or that other problems cannot be solved. Even if your path is blocked, there are probably alternative paths. Don’t give up. Keep going.

Making decisions is an important tool in our self-management toolbox. There are some steps that are a little like problem solving to help us make decisions.

1. Identify the options. For example, you may have to make a decision about getting help in the house or continuing to do all the work yourself. Sometimes the options are to change a behavior or to not change at all.

2. Identify what you want. It may be important for you to continue your life as normally as possible, to have more time with your family, or not have to shovel the walkways, cut the grass, or clean the house. Sometimes identifying your deepest, most important values (like spending time with family) helps set priorities and increase your motivation to change.

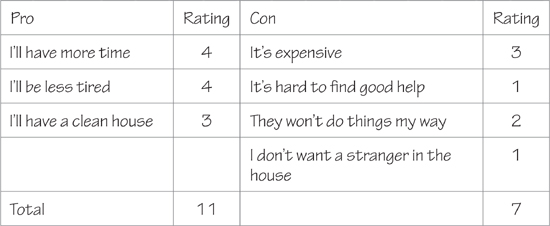

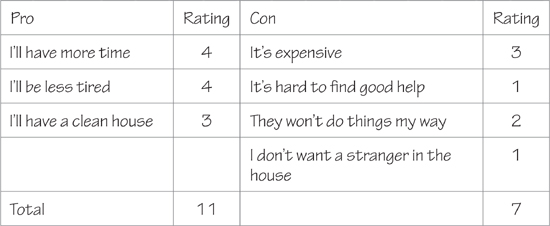

3. Write down pros and cons for each option. List as many items as you can for each side. Don’t forget the emotional and social effects.

4. Rate each item on the list on a 5-point scale with 0 indicating “not at all important” and 5 indicating “extremely important.”

5. Add up the ratings for each column and compare them. The column with the higher total should give you your decision. If the totals are close or you are still not sure, skip to the next step.

6. Apply the “gut test.” For example, does going back to work part-time feel right to you? If so, you have probably reached a decision. If not, the way you feel should probably win out over the math.

Should I get help in the house?

Add up the points for the pro and con lists. The decision in this example would be to get help because the pro score (11) is significantly higher than the con score (7). If this feels right in your gut, you have the answer.

Now it’s your turn! Try making a decision using the following chart. It’s OK to write in your book.

Decision to be made

The key to successful problem solving and decision making is taking action. We will talk about this next.

You have looked at a problem or made a difficult decision. Knowing what to do is not enough. It is time to do something, to take action. We suggest that you start by doing one thing at a time.

Before you can take action, you must decide what you want to do first. You must be realistic and specific when stating your goal. Think of all the things you would like to do. One self-manager wanted to climb 20 steps to her daughter’s home so that she could join her family for a holiday meal. Another wanted to overcome anxiety and attend social events. Still another wanted to continue to ride his motorcycle but could no longer lift his 1,000-pound bike when it was laying on the ground.

One of the problems with goals is that they often seem like dreams. They are so far off, big, or difficult that we are overwhelmed and don’t even try to accomplish them. We’ll tackle this problem next. For now, take a few minutes and write your goals below (add more lines if you need to).

Goals

_______________________________________

_______________________________________

_______________________________________

_______________________________________

Put a star ( ) next to the goal you would like to work on first.

) next to the goal you would like to work on first.

Don’t reject a goal until you have thought about alternatives. Sometimes we reject alternatives without knowing much about them. In the earlier example, our traveler was able to make a list of alternative travel arrangements and then chose the train.

There are many ways to reach any specific goal. For example, our self-manager who wanted to climb 20 steps could start off with a slow walking program, could start to climb a few steps each day, or could look into having the family gathering at a different place. The man who wanted to attend social events could start with going on very short outings, asking a friend to go along to help, using distraction techniques when feeling anxious, or talking to the health care team about therapy or medication. Our motorcycle rider could buy a lighter motorcycle, use a sidecar, put “training wheels” on his bike, buy a three-wheeled motorcycle, or give up riding.

As you can see, there are many options for reaching each goal. The job here is to list the options and then choose one or two to try out.

Sometimes it is hard to think of all the options yourself. If you are having problems, it is time to use a consultant. Share your goal with family, friends, and health professionals. You can call community organizations such as the American Heart Association or the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. You can use the Internet. Don’t ask what you should do. Rather, ask for suggestions. It is always good to have a list of options.

A note of caution: many options are never seriously considered because you assume they don’t exist or are unworkable. Never make this assumption until you have thoroughly investigated the option. One woman we know had lived in the same town all her life and felt that she knew all about the community resources. When she was having problems with her health insurance, a friend from another city suggested contacting an insurance counselor. However, the woman dismissed this suggestion because she was certain that this service did not exist in her town. It was only when, months later, the friend came to visit and called the Area Agency on Aging (which exists in most counties in the United States) that the woman learned that there were three insurance counseling services nearby. Our motorcycle rider thought that training wheels on a Harley was a crazy idea but investigated. He added 15 years to his riding life using training wheels. In short, never assume anything. Assumptions are major self-management enemies.

Write the list of options for your main goal here. Then put a star ( ) next to the two or three options on which you would like to work.

) next to the two or three options on which you would like to work.

Options

_______________________________________

_______________________________________

_______________________________________

_______________________________________

Once a decision has been made, we have a pretty good idea of where we are going. However, this goal may be overwhelming. How will I ever move, how will I ever be able to paint again, how will I ever by able to ___________________ (you fill in the blank)? The secret is to not try to do everything at once. Instead, look at what you can realistically expect to accomplish within the next week. We call this an action plan: something that is short-term, is doable, and sets you on the road toward your goal. The action plan should be about something you want to do or accomplish. It is a tool to help you do what you wish. Do not make action plans to please your friends, family, or doctor.

Action plans are probably your most important self-management tool. Most of us can do things to make us healthier but fail to do them. For example, most people with chronic illness can walk—some just across the room, others for half a block. Most can walk several blocks, and some can walk a mile or more. However, few people have a systematic exercise program.

An action plan helps us do the things we know we should do, but we should start with what we want to do. Let’s go through all the steps for making a realistic action plan.

First, decide what you will do this week. For a step climber, this might be climbing three steps on four consecutive days. The man who wants to continue riding his motorcycle might spend half an hour on two days researching lighter motorcycles and motorcycle training wheels.

Make very sure that your plans are “action-specific”; that is, rather than just deciding “to lose weight” (which is not an action but the result of an action), you will “replace soda with tea.”

Next, make a specific plan. Deciding what you want to do is worthless without a plan to do it. The plan should answer all of the following questions:

Exactly what are you going to do? Are you going to walk, how will you eat less, what distraction technique will you practice?

Exactly what are you going to do? Are you going to walk, how will you eat less, what distraction technique will you practice?

How much will you do? This question is answered with something like time, distance, portions, or repetitions. Will you walk one block, walk for 15 minutes, eat half portions at lunch and dinner, practice relaxation exercises for 15 minutes?

How much will you do? This question is answered with something like time, distance, portions, or repetitions. Will you walk one block, walk for 15 minutes, eat half portions at lunch and dinner, practice relaxation exercises for 15 minutes?

When will you do this? Again, this must be specific: before lunch, in the shower, upon coming home from work. Connecting a new activity with an old habit is a good way to make sure it gets done. Consider what comes right before your action plan that could trigger the new behavior. For example, brushing your teeth reminds you to take your medication. Another trick is to do your new activity before an old favorite activity such as reading the paper or watching a favorite TV program.

When will you do this? Again, this must be specific: before lunch, in the shower, upon coming home from work. Connecting a new activity with an old habit is a good way to make sure it gets done. Consider what comes right before your action plan that could trigger the new behavior. For example, brushing your teeth reminds you to take your medication. Another trick is to do your new activity before an old favorite activity such as reading the paper or watching a favorite TV program.

How often will you do the activity? This is a bit tricky. We would all like to do things every day, but that is not always possible. It is usually best to decide to do an activity three or four times a week to give yourself “wiggle room” if something comes up. If you do more, so much the better. However, if you are like most people, you will feel less pressure if you can do your activity three or four times a week and still feel successful. (Note that taking medications is an exception. This must be done exactly as directed by your doctor.)

How often will you do the activity? This is a bit tricky. We would all like to do things every day, but that is not always possible. It is usually best to decide to do an activity three or four times a week to give yourself “wiggle room” if something comes up. If you do more, so much the better. However, if you are like most people, you will feel less pressure if you can do your activity three or four times a week and still feel successful. (Note that taking medications is an exception. This must be done exactly as directed by your doctor.)

There are some general guidelines for writing your action plan that may help. First, start where you are or start slowly. If you can walk for only one minute, start your walking program by walking one minute once every hour or two, not by trying to walk a block. If you have never done any exercise, start with a few minutes of warm-up. A total of 5 or 10 minutes is enough. If you want to lose weight, set a goal based on your existing eating behaviors, such as having half portions. For example, “losing a pound this week” is not an action plan because it does not involve a specific action; “not eating after dinner for 4 days this week,” by contrast, would be a fine action plan.

Second, give yourself some time off. All people have days when they don’t feel like doing anything. That is a good reason for saying that you will do something three times a week instead of every day.

Third, once you’ve made your action plan, ask yourself the following question: “On a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being totally unsure and 10 being totally certain, how sure am I that I can complete this entire plan?”

If your answer is 7 or above, this is probably a realistic action plan. If your answer is below 7, you should look again at your action plan. Ask yourself why you are unsure. What problems do you foresee? Then see if you can either solve the problems or change your plan to make yourself more confident of success.

Once you have made a plan you are happy with, write it down and post it where you will see it every day. Thinking through an action plan is one thing. Writing it down makes it more likely you will take action. Keep track of how you are doing and the problems you encounter. (A blank action plan form is provided at the end of this chapter. You may wish to make photocopies of it to use weekly.)

If the action plan is well written and realistically achievable, completing it is generally pretty easy. Ask family or friends to check with you on how you are doing. Having to report your progress is good motivation. Keep track of your daily activities while carrying out your plan. Many good managers have lists of what they want to accomplish. Check things off as they are completed. This will give you guidance on how realistic your planning was and will also be useful in making future plans. Make daily notes, even of the things you don’t understand at the time. Later these notes may be useful in establishing a pattern to use for problem solving.

For example, our stair-climbing friend never did her climbing. Each day she had a different problem: not enough time, being tired, the weather being too cold, and so on. When she looked back at her notes, she began to realize that the real problem was her fear of falling with no one around to help her. She then decided to use a cane while climbing stairs and to do it when a friend or neighbor was around.

At the end of each week, see if you completed your action plan and if you are any nearer to accomplishing your goal. Are you able to walk farther? Have you lost weight? Are you less anxious? Taking stock is important. You may not see progress day by day, but you should see a little progress each week. At the end of each week, check on how well you have fulfilled your action plan. If you are having problems, this is the time to use your problem-solving skills.

When you are trying to overcome obstacles, the first plan is not always the most workable plan. If something doesn’t work, don’t give up. Try something else; modify your short-term plans so that your steps are easier, give yourself more time to accomplish difficult tasks, choose new steps toward your goal, or check with your consultants for advice and assistance. If you are not sure how to go about this, go back and read page 16.

The best part of being a good self-manager is the reward that comes from accomplishing your goals and living a fuller and more comfortable life. However, don’t wait until your goal is reached; rather, reward yourself frequently for your short-term successes. For example, decide that you won’t read the paper until after you exercise. Thus reading the paper becomes your reward. One self-manager buys only one or two pieces of fruit at a time and walks the half-mile to the supermarket every day or two to get more fruit. Another self-manager who stopped smoking used the money he would have spent on cigarettes to have his house professionally cleaned, and there was even enough left over to go to a baseball game with a friend. Rewards don’t have to be fancy, expensive, or fattening. There are many healthy pleasures that can add enjoyment to your life.

One last note: not all goals are achievable. Chronic illness may mean having to give up some options. If this is true for you, don’t dwell too much on what you can’t do. Rather, start working on another goal you would like to accomplish. One self-manager we know who uses a wheelchair talks about the 90% of things he can do. He devotes his life to developing this 90% to the fullest.

Now that you understand the meaning of self-management, you are ready to begin learning to use the tools that will make you a successful one. Most self-management skills are similar for all diseases. Chapters 15 through 18 contain information on some of the more common chronic illnesses. If your illness is not covered, we apologize. If we had included everything, you would not be able to carry this book. We talk about medications and their uses in Chapter 13. The rest of the book is devoted to tools of the trade. These include exercise, nutrition, symptom management, preventing falls, communication, making decisions about the future, finding resources and information about advance directives for health care, and sex and intimacy.

In writing your action plan, be sure it includes all of the following:

1. What you are going to do (a specific action)

2. How much you are going to do (time, distance, portions, repetitions, etc.)

3. When you are going to do it (time of the day, day of the week)

4. How often or how many days a week you are going to do it

Example: This week, I will walk (what) around the block (how much) before lunch (when) three times (how many).

This week I will _______________________________________ (what)

_______________________________________________ (how much)

___________________________________________________ (when)

_______________________________________________ (how often)

How sure are you? (0 = not at all sure; 10 = absolutely sure) _____

Comments

Monday _________________________________________________

Tuesday _________________________________________________

Wednesday ______________________________________________

Thursday ________________________________________________

Friday __________________________________________________

Saturday ________________________________________________

Sunday _________________________________________________