Chapter 5

The Passing Game

In This Chapter

Catching up with the receivers

Catching up with the receivers

Getting a handle on common passing-game terms

Getting a handle on common passing-game terms

Finding out about different pass patterns

Finding out about different pass patterns

Although the strategies of offenses change and sometimes favor running over passing, throwing the football is a major part of football’s excitement. Some of the most memorable plays in football are those long passes (or throws) that win games in the final seconds or pull a team ahead in the score and turn the game around. Who can resist joining in the collective cheer that erupts when the ball is hurtling through the air and looks as if it’s about to drop into a receiver’s hands? And when the defense catches the ball (known in football jargon as an interception), the play can be just as exciting and influential to the outcome of the game.

An offense scores points by moving the ball into the opponent’s end zone. This chapter focuses on one half of the offensive attack: the passing game. The other half, the running game, is covered in Chapter 6. In the 1980 NFL season, pass plays exceeded running plays for the first time since 1969, and that trend has continued ever since.

Getting to Know the Passing Game

To many fans, the passing game is the most exciting aspect of football. Seeing the quarterback throwing a long pass and a fleet-footed receiver jumping up to grab it is exciting. Earl “Curly” Lambeau, the founder and player/coach of the Green Bay Packers, made his offenses throw the football in the mid-1930s. But teams eventually moved away from throwing the ball. In the 1960s and 1970s, the running game and zone defenses (where players defended deep and covered every area of the field) choked the life out of the passing game.

Two significant rule changes in 1978 spurred the growth of the passing game in the NFL. First, defenders were permitted to make contact with receivers only within 5 yards of the line of scrimmage. Previously, defenders were allowed to hit, push, or shove (“chuck”) a receiver anywhere on the field. (In 2014, NFL officials were instructed to pay close attention to illegal contact by defenders against receivers, further opening up the passing game.) Also, offensive linemen were allowed to use open hands and fully extend their arms to block a pass-rusher. The liberalization of this offensive blocking technique led to better protection for the quarterback and ultimately more time for him to throw the football.

Prior to these rules, offenses had begun to rely on running backs as their main pass receivers. Then Bill Walsh became the head coach of the San Francisco 49ers in 1979, and he melded every aspect of these new rules and the running-back-as-receiver concept into his West Coast offense. For the first time, teams were running out of passing formations, and the pass was setting up running plays instead of vice versa.

To make a pass successful, quarterbacks and receivers (wide receivers, tight ends, and running backs) must work on their timing daily. To do so, the receivers must run exact pass patterns with the quarterback throwing the football to predetermined spots on the field. Although passing the football may look like a simple act of the quarterback throwing and a receiver catching the ball (often in full stride), this aspect of the game is very complex. For it to be successful, the offensive linemen must provide the quarterback with adequate protection so that he has time to throw the football (more than two seconds), while the receivers make every attempt to catch the ball, even if it’s poorly thrown. Sometimes, a receiver must deviate from his planned route and run to any open space to give the quarterback a target.

To make a pass successful, quarterbacks and receivers (wide receivers, tight ends, and running backs) must work on their timing daily. To do so, the receivers must run exact pass patterns with the quarterback throwing the football to predetermined spots on the field. Although passing the football may look like a simple act of the quarterback throwing and a receiver catching the ball (often in full stride), this aspect of the game is very complex. For it to be successful, the offensive linemen must provide the quarterback with adequate protection so that he has time to throw the football (more than two seconds), while the receivers make every attempt to catch the ball, even if it’s poorly thrown. Sometimes, a receiver must deviate from his planned route and run to any open space to give the quarterback a target.

Recognizing the Role of Receivers

A quarterback wouldn’t be much good without receivers to catch the ball. Wide receivers and tight ends are the principal players who catch passes, although running backs also are used extensively in every passing offense. (See Chapter 6 for more on running backs.) During the 2014 season, 23 players in the NFL had over 1,000 receiving yards, and of those 23, only 2 were tight ends. The rest were wide receivers.

Receivers come in all sizes and shapes. They are tall, short, lean, fast, and quick. To excel as a receiver, a player must have nimble hands (hands that are very good at catching the ball) and the ability to concentrate under defensive duress; he must also be courageous under fire and strong enough to withstand physical punishment. Although receiving is a glamorous job, every team expects its receivers to block defensive backs on running plays as well (head to Chapter 7 to find out more). Every team wants its receivers to be able to knock a defensive cornerback on his back or at least prevent him from making a tackle on a running back.

Tight ends aren’t as fast as wide receivers because they play the role of heavy-duty blockers on many plays. Teams don’t expect tight ends, who may outweigh a wide receiver by 60 pounds, to have the bulk and strength of offensive linemen, but the good ones — like Vernon Davis of the San Francisco 49ers and Rob Gronkowski of the New England Patriots — are above-average blockers as well as excellent receivers.

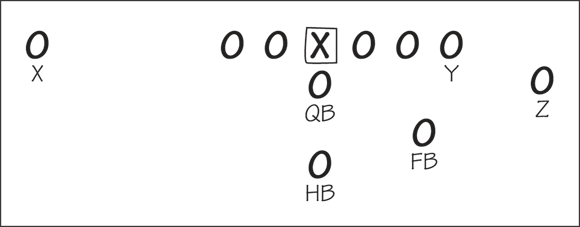

Basic offenses have five possible receivers: the two running backs, the tight end, and the two wide receivers. The wide receivers are commonly referred to as X and Z receivers. The X receiver, or split end, normally aligns to the weak side of the formation, and the Z receiver, or flanker, aligns to the strong side of the formation. The tight end is known as the Y receiver. (In simplest terms, the strong side of the formation is the side with the most distance to the sideline.)

Basic offenses have five possible receivers: the two running backs, the tight end, and the two wide receivers. The wide receivers are commonly referred to as X and Z receivers. The X receiver, or split end, normally aligns to the weak side of the formation, and the Z receiver, or flanker, aligns to the strong side of the formation. The tight end is known as the Y receiver. (In simplest terms, the strong side of the formation is the side with the most distance to the sideline.)

The split end received his name because he was the end (the offenses of the 1930s used two ends) who aligned 10 yards away from the base offensive formation. Hence, he split from his teammates. The other end, the tight end, aligned next to an offensive tackle. The flanker position was originally a running back, and as offenses developed, he flanked to either side of the formation, but never on the line of scrimmage like the split end and tight end.

In many offenses, on passing downs, the tight end is replaced by another receiver. In Figure 5-1, the Y receiver is the one who replaces the tight end.

The following sections offer insight into the nitty-gritty details of the receiver’s role in the passing game. Read on to find out everything from the stance that receivers use to the ways they overcome man-to-man coverage.

Achieving the proper stance

Before receivers work on catching the ball, they need to learn the proper stance to create acceleration off the line of scrimmage while also using their upper bodies to defend themselves from contact with defensive backs. Receivers must understand, even at the beginning level, that they must get open before they can catch the ball and that the proper stance enables them to explode from the line of scrimmage. A quarterback won’t throw the ball to a receiver who isn’t open, and when it comes to being able to complete a pass to an open receiver, every step counts.

In the stand-up stance, the receiver’s feet remain shoulder width apart and are positioned like they’re in the starting blocks — with his left foot near the line of scrimmage and his right foot back 18 inches. With his shoulders square to the ground, he should lean forward just enough so that he can explode off the line when the ball is snapped. The receiver’s lean shouldn’t be exaggerated, though, or he may tip over.

A good receiver uses the same stance on every play because he doesn’t want to tip off the defense to whether the play is a run or a pass. Bad receivers line up lackadaisically on running plays.

A good receiver uses the same stance on every play because he doesn’t want to tip off the defense to whether the play is a run or a pass. Bad receivers line up lackadaisically on running plays.

Lining up correctly

One wide receiver, usually the split end, lines up on the line of scrimmage. The other receiver, the flanker, must line up 1 yard behind the line of scrimmage. A combination of seven offensive players must always be on the line of scrimmage prior to the ball being snapped. A smart receiver checks with the nearest official to make sure he’s lined up correctly.

The tight end and the split end never line up on the same side. If a receiver is aligned 15 to 18 yards away from the quarterback, he can’t hear the quarterback barking signals. Therefore, he must look down the line and move as soon as he sees the ball snapped. Once off the line of scrimmage, a receiver should run toward either shoulder of a defensive back, forcing the defender to turn his shoulders perpendicular to the line of scrimmage to cover him. The receiver hopes to turn the defender in the direction that’s opposite of the one in which he intends to go.

Catching the ball

Good receivers catch a football with their hands while their arms are extended away from their bodies. They never catch a football by cradling it in their shoulders or chest, because the ball frequently bounces off.

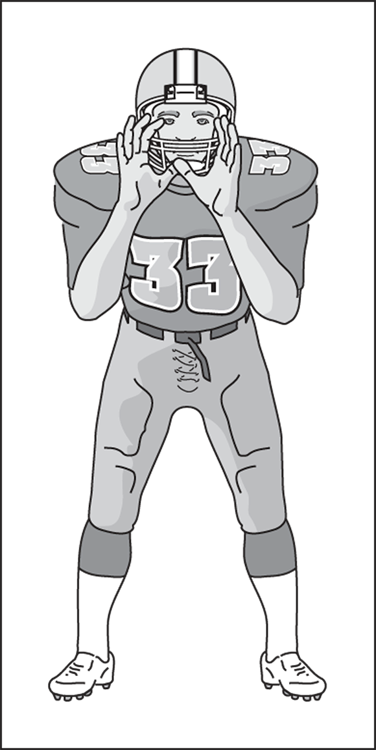

The best technique a receiver has for using his hands is to place one thumb behind the other while turning his hands so that the fingers of both hands face each other. He spreads his hands as wide as possible while keeping his thumbs together. Then he brings his hands face-high, like he’s looking through a tunnel (see Figure 5-2). He wants the ball to come through that tunnel. He wants to see the point of the ball coming down the tunnel, and then he wants to trap it with his palms, thumbs, and fingers. This technique is called getting your eyes in line with the flight of the ball. If a ball is thrown below a receiver’s waist, he should turn his thumbs out and his little fingers should overlap. A receiver with good fundamentals also keeps his elbows close to his body when catching a football, which adds power to his arms.

Beating man-to-man coverage

Man-to-man coverage is a style, like in basketball, in which one man guards (or defends) another. The defender stays with a single receiver no matter where he runs. His responsibility is to make sure the receiver doesn’t catch a pass. (Head to Chapter 10 for more on man-to-man coverage.)

Defensive players use the in-your-face technique of putting their bodies on the line of scrimmage and trying to knock the receivers off stride and out of their routes (see the later section “Looking at Passing Patterns” for more info on routes). The defensive back’s objective is to “hurt” the receiver first and then try to push him out of bounds (it’s illegal for a receiver to return to the field and catch a pass) while trying to get the receiver’s mind off running a perfect route and making a catch. The entire defensive attitude is to take the receiver out of the game, mentally and physically.

A receiver must approach this in-your-face technique as if he’s in an alley fight against someone who wants to take him down. When the center snaps the ball, the receiver must bring his arms and hands up to his face just like a fighter would. The receiver wants to prevent the defensive player from putting his hands into his chest by counter-punching his attempts. The working of the receiver’s hands is similar to the “wax on, wax off” style taught in the movie The Karate Kid.

After the receiver fights off the defensive back’s hands, he must dip his shoulder and take off running. This technique is called dip and rip because the receiver dips his shoulder and rips through the defender’s attempt to hold or shove him with a strong punch, like a boxer throwing a great uppercut to his opponent’s chin. This move was a favorite of Hall-of-Famer Jerry Rice, who’s possibly the greatest receiver of all time.

Another method of defeating man-to-man coverage is to use the swim technique. With the swim, the receiver’s arms and hands are still in the same position as the dip and rip, and the receiver must again get his hands up in a boxing position. But at the snap of the ball, instead of lowering his shoulder and ripping through, the receiver tries to slap the defensive back’s hands one way while heading in the opposite direction. When the defensive back reacts, the receiver uses his free arm and takes a freestyle stroke (raises an arm up and forward and then brings it back to the side) over the defensive back while trying to pull the arm back underneath and behind him. This entire action takes a split second. With the swim technique, it’s critical that the receiver doesn’t allow the defensive back to catch his arm and grab hold under his armpit to prevent him from running downfield.

Note:

Bigger, stronger receivers use the dip and rip method, whereas smaller, faster receivers usually use the swim technique.

Defining Important Passing Terms

This section lists the words and descriptions frequently mentioned when discussing the passing game. As a player, my favorite word was sack: a defender’s dream and a quarterback’s nightmare (you can find a definition in the following list). I had 84 sacks in my career, every one a great thrill. I deflected quite a few pass attempts, too. Read on and you’ll get my meaning:

-

Deflection: A deflection happens when a defensive player uses his hands or arms to knock down (or deflect) a pass before it reaches the receiver. This act usually occurs near the line of scrimmage when defensive linemen jump, arms raised, into a quarterback’s visual passing lane, hoping to deflect the pass. Deflections can lead to an interception or incompletion.

-

Holding: Holding is the most common penalty called against the offense when it’s attempting to pass. The offense receives a 10-yard penalty (and repeat of down) when any offensive player holds a defensive player by grabbing his jersey or locking his arm onto the defensive player’s arm while that player is trying to sack the quarterback. This penalty is also known as illegal use of the hands, arms, or any part of the body.

-

Illegal forward pass: A quarterback can’t cross the line of scrimmage and throw the ball. This penalty often occurs when the quarterback runs forward, attempting to evade defensive players, and forgets where the line of scrimmage is. The offense is penalized 5 yards from the spot of the foul and loses a down.

-

Intentional grounding: This penalty occurs when a quarterback standing in the pocket deliberately throws the ball out of bounds or into the ground. It can be interpreted in the following three ways, with the first two drastically penalizing the offense:

-

No. 1: The quarterback is attempting to pass from his own end zone and, prior to being tackled, intentionally grounds the ball, throwing it out of bounds or into the ground. The defense is awarded a safety, worth two points, and the offense loses possession of the ball and has to kick the ball from its own 20-yard line. (NFL teams usually kick off from the 30-yard line.)

-

No. 2: The quarterback is trapped behind his own line of scrimmage and intentionally grounds the ball for fear of being tackled for a loss. This penalty is a loss of down, and the ball is placed at the spot of the foul, which in this case is where the quarterback was standing when he grounded the ball. Otherwise, the intentional grounding penalty calls for loss of down and 10 yards.

-

No. 3: The quarterback steps back from the center and immediately throws the ball into the ground, intentionally grounding it. This is referred to as spiking the ball. This play is common when an offense wants to stop the clock without calling a timeout because it either wants to preserve its timeouts or is out of timeouts. For this type of intentional grounding, the penalty is simply a loss of a down.

-

Interception: An interception is the act of any defensive player catching a pass. Along with a fumble, an interception is the worst thing that can happen to a quarterback and his team. It’s called a turnover because the defensive team gains possession of the ball and is allowed to run with the ball in an attempt to score. (Deion Sanders was probably the greatest threat on an interception because of his open-field running ability.)

-

Roughing the passer: This penalty was devised to protect the quarterback from injury. After the ball leaves the quarterback’s hand, any defensive player must attempt to avoid contact with him. Because a defensive player’s momentum may cause him to inadvertently run into the quarterback, he’s allowed to take one step after he realizes that the ball has been released. But if he hits the quarterback on his second step, knowing that the ball is gone, the referee (the official standing near the quarterback) can call roughing. It’s a 15-yard penalty against the defense and an automatic first down. This penalty is difficult to call unless the defensive player clearly hits the quarterback well after the quarterback releases the ball. After all, it’s pretty tough for defensive ends, who are usually over 6 feet and weigh 250 pounds, to come to an abrupt stop from a full sprint.

Roughing the passer penalties can also be called on defenders who

-

Strike the quarterback in the head or neck area, regardless of whether the hit was intentional

-

Flagrantly hit the quarterback in the knee area or lower when the defender has an unrestricted path to the quarterback

Keep in mind that these penalties apply only when the quarterback is acting as a passer. If the quarterback tucks the ball and runs, defenders can hit him just like any other ball carrier. However, quarterbacks have the option of giving themselves up while running, which basically means that they slide feet first to avoid being hit. If a defender hits a sliding quarterback, he’s assessed a 15-yard unnecessary roughness penalty.

-

Sack: A sack happens when the quarterback is tackled behind the line of scrimmage by any defensive player. The sack is the most prominent defensive statistic, one the NFL has officially kept since 1982. (All other kinds of tackles are considered unofficial statistics because individual teams are responsible for recording them.) Colleges have been recording sacks for the same length of time.

-

Trapping: Receivers are asked to make a lot of difficult catches, but this one is never allowed. Trapping is when a receiver uses the ground to help him catch a pass that’s thrown on a low trajectory. For an official to not rule a reception a trap, the receiver must make sure either his hands or his arms are between the ball and the ground when he makes a legal catch. Often, this play occurs so quickly, only instant replay can show that the receiver wasn’t in possession of the ball — instead it shows that he trapped it.

Looking at Passing Patterns

When watching at home or in the stands, you can look for basic pass patterns used in all levels of football. These pass patterns (also known as pass routes) may be a single part of a larger play. In fact, on a single play, two or three receivers may be running an equal number of different pass patterns.

By knowing passing patterns, you can discover what part of the field or which defensive player(s) the offense wants to attack, or how an offense wants to compete with a specific defense. (Sometimes, a pass pattern is run to defeat a defensive scheme designed to stop a team’s running game by moving defenders away from the actual point of attack.) The following list includes the most common patterns receivers run during games:

By knowing passing patterns, you can discover what part of the field or which defensive player(s) the offense wants to attack, or how an offense wants to compete with a specific defense. (Sometimes, a pass pattern is run to defeat a defensive scheme designed to stop a team’s running game by moving defenders away from the actual point of attack.) The following list includes the most common patterns receivers run during games:

-

Comeback: Teams use this pass pattern effectively when the receiver is extremely fast and the defensive player gives him a 5-yard cushion, which means that the defensive player stays that far away from him, fearing his speed. On the comeback, the receiver runs hard downfield, between 12 and 20 yards, and then turns sharply to face the football. The comeback route generally is run along the sideline. To work effectively, the quarterback usually throws the ball before the receiver turns. He throws to a spot where he expects the receiver to stop and turn. This kind of pass is called a timing pass because the quarterback throws it before the receiver turns and looks toward the quarterback or before he makes his move backward.

-

Crossing: The crossing pattern is an effective pass against man-to-man coverage because it’s designed for the receiver to beat his defender by running across the field. The receiver can line up on the right side of the line of scrimmage, run straight for 10 yards, and then cut quickly to his left. When the receiver cuts, he attempts to lose the man covering him with either a head or shoulder fake (a sudden jerk with his upper body to one side or the other) or a quick stutter-step. This route is designed for two receivers, usually one on either side of the formation. It allows one receiver to interfere with his teammate’s defender as the two receivers cross near the middle of the field. The play is designed for the quarterback to pass to the receiver on the run as the receiver crosses in front of his field of vision.

-

Curl: For this 8- to 12-yard pass beyond the line of scrimmage, the receiver stops and then turns immediately, making a slight curl before facing the quarterback’s throw. The receiver usually takes a step or two toward the quarterback and the ball before the pass reaches him. The curl tends to be a high-percentage completion because the receiver wants to shield the defender with his back, and the intention is simply to gain a few yards. Big tight ends tend to like the curl.

-

Hook: This common pass play, which is also known as a buttonhook, is designed mostly for a tight end, who releases downfield and then makes a small turn, coming back to face the quarterback and receive the ball. A hook is similar to a curl, except the turn is made more abruptly and the pass is shorter, at 5 to 8 yards. It’s a timing pass, so the quarterback usually releases the ball before the tight end starts his turn.

-

Post: This is a long pass, maybe as long as 40 to 50 yards, in which the receiver runs straight downfield, and then cuts on a 45-degree angle toward the “post,” or goalposts. (Most teams use the hash marks as a guiding system for both the quarterback and the receiver.) A coach calls this play when one safety is deep and the offense believes it can isolate a fast receiver against him. The receiver runs straight downfield, possibly hesitating a split second as if he might cut the route inside or outside, and then cuts toward the post. The hesitation may cause the safety, or whoever is positioned in the deep center of the field, to break stride or slow down. The receiver needs only an extra step on the defender for this play to be successful. The quarterback puts enough loft on the ball to enable the receiver to catch the pass in stride.

-

Slant: This pass is designed for an inside receiver (a flanker) who’s aligned 5 yards out from the offensive line, possibly from a tight end or the offensive tackle. The receiver runs straight for 3 to 8 yards and then slants his route, angling toward the middle of the field. A slant is effective against both zone and man-to-man coverage because it’s designed to find an open space in either defensive scheme (see Chapter 10 for details on both of these types of coverage).

-

Square-out: The receiver on this pattern runs 10 yards down the field and then cuts sharply toward the sideline, parallel to the line of scrimmage. The square-out is also a timing play because the quarterback must deliver the pass before the receiver reaches the sideline and steps out of bounds, sometimes before he even cuts. The quarterback must really fire this pass, which is why commentators sometimes refer to it as a bullet throw. The route works against both man-to-man and zone coverage. The receiver must roll his shoulder toward the inside before cutting toward the sideline. The quarterback throws the pass, leading the receiver toward the sideline.

-

Streak (or Fly): This is a 20- to 40-yard pass, generally to a receiver on the quarterback’s throwing side (which is right if he’s right-handed or left if he’s left-handed). The receiver, who’s aligned wide and near the sidelines, runs as fast as he can down the sideline, hoping to lose the defensive man in the process. This pass must be thrown accurately because both players tend to be running as fast as they can, and often the cornerback is as fast as the receiver. This play is designed to loosen up the defense, making it believe the quarterback and the receiver have the ability to throw deep whenever they want to. Moving a defense back or away from the line of scrimmage allows the offense an opportunity to complete shorter passes and execute run plays. To complete this pass, the quarterback makes sure a safety isn’t playing deep to that side of the field. Otherwise, with the ball in the air for a long time, a free safety can angle over and intercept the pass. If the quarterback sees the safety near his streaking receiver, he must throw to another receiver elsewhere on the field.

-

Swing: This is a simple throw to a running back who runs out of the backfield toward the sideline. The quarterback generally throws the pass when the running back turns and heads upfield. The swing is usually a touch pass, meaning the quarterback doesn’t necessarily throw it as hard as he does a deep square-out (described earlier in this list). He wants to be able to float it over a linebacker and make it easy for the running back to catch. The area in which the back is running is known as the flat because it’s 15 yards outside the hash marks and close to where the numbers on the field are placed. The receiver’s momentum most likely will take him out of bounds after he catches the ball unless he’s able to avoid the first few tacklers he faces.

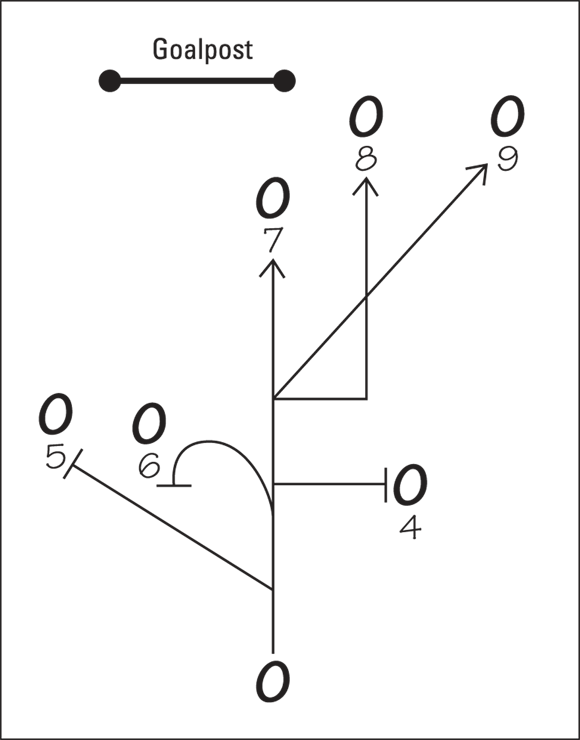

Figure 5-3 shows the many pass patterns and how they funnel off what’s called a route tree. The tree is numbered: 4 is a square-out; 5 is a slant; 6 is a curl or a hook; 7 is a post; 8 is a streak or fly; and 9 is a corner route. When calling a pass play, these numbers, which can vary by team, refer to the specific pass pattern (or route) called by the quarterback.

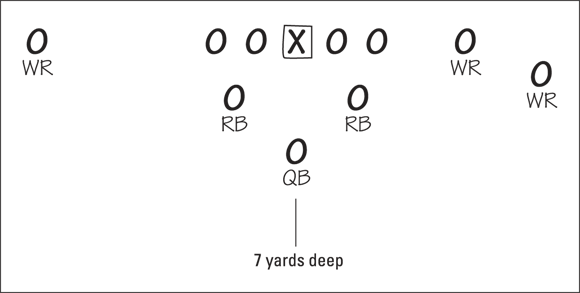

Getting into the Shotgun Formation

In football terminology, formation describes how the players on offense line up before the ball is snapped. As football has evolved, so have the formations. The shotgun passing formation was devised by San Francisco 49ers head coach Red Hickey in 1960. Hickey feared the Baltimore Colts’ great pass rush, so he had his quarterback, John Brodie, line up 7 yards behind the line of scrimmage (see Figure 5-4). Hickey figured that Brodie would have more time to see his receivers and could release the ball before the defensive rush reached him. The strategy worked, and the 49ers upset the mighty Colts.

Offenses use the shotgun when they have poor pass blocking or when they’re facing excellent pass rushers. Teams also use the shotgun when they want to pass on every down, usually when they’re behind. However, many offenses use the shotgun simply because the quarterback and the coach like to use it. Other teams use the shotgun only when they’re in obvious passing situations — such as on third down when they need 4 or more yards for a first down, or anytime they need more than 10 yards for a first down.

Despite its versatility, the shotgun formation has a couple downsides:

Despite its versatility, the shotgun formation has a couple downsides:

-

The center must be able to make an accurate, chest-high, 7-yard snap to the quarterback.

-

You can’t fool the defensive players; they know you’re probably throwing the ball, and the pass rushers won’t hesitate to sprint for your quarterback in hopes of a sack.

Teams need a quick-thinking quarterback who can set his feet quickly in order to use the shotgun formation effectively.

Catching up with the receivers

Catching up with the receivers Getting a handle on common passing-game terms

Getting a handle on common passing-game terms Finding out about different pass patterns

Finding out about different pass patterns To make a pass successful, quarterbacks and receivers (wide receivers, tight ends, and running backs) must work on their timing daily. To do so, the receivers must run exact pass patterns with the quarterback throwing the football to predetermined spots on the field. Although passing the football may look like a simple act of the quarterback throwing and a receiver catching the ball (often in full stride), this aspect of the game is very complex. For it to be successful, the offensive linemen must provide the quarterback with adequate protection so that he has time to throw the football (more than two seconds), while the receivers make every attempt to catch the ball, even if it’s poorly thrown. Sometimes, a receiver must deviate from his planned route and run to any open space to give the quarterback a target.

To make a pass successful, quarterbacks and receivers (wide receivers, tight ends, and running backs) must work on their timing daily. To do so, the receivers must run exact pass patterns with the quarterback throwing the football to predetermined spots on the field. Although passing the football may look like a simple act of the quarterback throwing and a receiver catching the ball (often in full stride), this aspect of the game is very complex. For it to be successful, the offensive linemen must provide the quarterback with adequate protection so that he has time to throw the football (more than two seconds), while the receivers make every attempt to catch the ball, even if it’s poorly thrown. Sometimes, a receiver must deviate from his planned route and run to any open space to give the quarterback a target.

By knowing passing patterns, you can discover what part of the field or which defensive player(s) the offense wants to attack, or how an offense wants to compete with a specific defense. (Sometimes, a pass pattern is run to defeat a defensive scheme designed to stop a team’s running game by moving defenders away from the actual point of attack.) The following list includes the most common patterns receivers run during games:

By knowing passing patterns, you can discover what part of the field or which defensive player(s) the offense wants to attack, or how an offense wants to compete with a specific defense. (Sometimes, a pass pattern is run to defeat a defensive scheme designed to stop a team’s running game by moving defenders away from the actual point of attack.) The following list includes the most common patterns receivers run during games: