Chapter 10

The Secondary: Last Line of Defense

In This Chapter

Meeting the secondary’s members: Cornerbacks, safeties, and nickel and dime backs

Meeting the secondary’s members: Cornerbacks, safeties, and nickel and dime backs

Getting to know the tricks of the secondary trade

Getting to know the tricks of the secondary trade

Recognizing the difference between zone and man-to-man coverages

Recognizing the difference between zone and man-to-man coverages

Understanding the eight men in a box and Nickel 40 coverage variations

Understanding the eight men in a box and Nickel 40 coverage variations

The secondary is the name given to the group of players who make up the defensive backfield. The basic defensive backfield consists of four position players: a right cornerback, a left cornerback, a strong safety, and a free safety. The secondary is the final line of defense, right after the defensive line and the linebackers (head to Chapter 9 for details on these defenders). The players who make up the secondary are known collectively as defensive backs, or DBs. Basically, their job is to tackle runners who get past the defensive line and the linebackers and to defend — and hopefully break up — pass plays.

Depending on the defensive scheme the coaching staff employs, the secondary can consist of anywhere from three to seven defensive backs on the field at the same time. (In rare instances, I’ve even seen eight defensive backs on the field at once.) However, most conventional defensive alignments use four defensive backs: two cornerbacks and two safeties. If all of this sounds confusing, never fear — this chapter is here to help you understand how and why a secondary acts in a particular way.

Be aware that a majority of big offensive plays (gains of 25 yards or more) and touchdowns come from the offense’s ability to execute the passing game. Therefore, on the defensive side of the ball, a great deal of attention on television is devoted to the secondary. Often, a defensive back is in proper position or has good coverage technique, but the offensive receiver still catches the pass. Other times, the secondary player is out of position, failing to execute his assignment, or is physically beaten by a better athlete. If you know the difference and what to look for, you’ll be regarded as an expert.

Be aware that a majority of big offensive plays (gains of 25 yards or more) and touchdowns come from the offense’s ability to execute the passing game. Therefore, on the defensive side of the ball, a great deal of attention on television is devoted to the secondary. Often, a defensive back is in proper position or has good coverage technique, but the offensive receiver still catches the pass. Other times, the secondary player is out of position, failing to execute his assignment, or is physically beaten by a better athlete. If you know the difference and what to look for, you’ll be regarded as an expert.

Presenting the Performers

All the players who make up the secondary are called defensive backs, but that category is further divided into the following positions: cornerbacks, safeties, and nickel and dime backs. In a nutshell, these players are responsible for preventing the opponent’s receivers from catching the ball. If they fail, they must then make the tackle, preventing a possible touchdown. The different players work in slightly different ways, as you find out in the following sections.

Cornerbacks

The cornerback is typically the fastest of the defensive backs. For example, Deion Sanders, who played on Super Bowl championship teams in the 1990s with the San Francisco 49ers and the Dallas Cowboys, had Olympic-caliber speed and the explosive burst necessary for this position. The burst is when a secondary player breaks (or reacts) to the ball and the receiver, hoping to disrupt the play.

The ideal NFL cornerback can run the 40-yard dash in 4.4 seconds, weighs between 180 and 190 pounds, and is at least 6 feet tall. However, the average NFL cornerback is about 5 feet 10 inches tall. Although speed and agility remain the necessary commodities, height is becoming a factor in order to defend the ever-increasing height of today’s wide receivers. How many times have you seen a great little cornerback like Antoine Winfield, who’s 5 feet 9 inches, put himself in perfect position simply to be out-jumped for the ball by a much taller receiver with longer arms?

The ultimate thrill for a cornerback is the direct challenge he faces on virtually every play, but this is especially true on passing downs. A defensive lineman can win 70 percent of his battle against an offensive lineman and leave the field feeling relieved. However, the same odds don’t necessarily apply to a cornerback. He can’t afford to lose many challenges because he’s exposed one-on-one with a receiver. If his man catches the ball, everyone in the stadium or watching on television can see. And if he’s beaten three out of ten times for gains over 25 yards, he may be in the unemployment line or find himself demoted come Monday. Cornerback is a job that accepts no excuses for poor performance. The next sections describe the cornerback’s role in two specific types of coverage.

Cornerbacks in man-to-man coverage

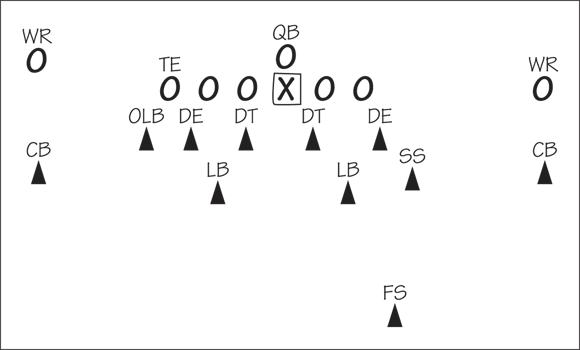

Most defensive schemes employ two cornerbacks (CB) in man-to-man coverage (which I explain further in the later “Man-to-man coverage” section) against the offense’s wide receivers (WR), as shown in Figure 10-1. The cornerbacks align on the far left and right sides of the line of scrimmage, at least 10 to 12 yards from their nearest teammate (usually a linebacker or defensive end) and opposite the offense’s wide receivers. The distance varies depending on where the offensive receivers align themselves. Cornerbacks must align in front of them.

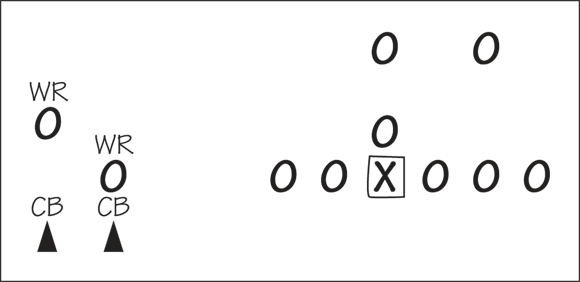

Most teams attempt to place their best cornerbacks against the opposition’s best receivers. Coaches generally know who these players are and design their defenses accordingly. Often, they simply need to flop cornerbacks from one side to the other. Some offensive formations place a team’s two best receivers on the same side of the field, requiring the defense to place both of its cornerbacks accordingly, as in Figure 10-2.

Cornerbacks in zone coverage

Cornerbacks are also used in zone coverage (which I fill you in on in the later “Zone coverage” section). If a team’s cornerbacks are smaller and slower than its opponent’s receivers, that team usually plays more zone coverages, fearing that fast receivers will expose its secondary’s athletic weaknesses. However, if you have two talented cornerbacks, like the Cincinnati Bengals had in the 2010 season with Leon Hall and Johnathan Joseph, your team can play more man-to-man coverage.

Safeties

Most defenses employ two safeties — a strong safety and a free safety. Safeties often are called the defense’s quarterbacks, or the quarterbacks of the secondary. They must see and recognize the offense’s formations and instruct their teammates to make whatever coverage adjustments are necessary. These instructions are different from what the middle linebacker (whom I describe in Chapter 9) tells his teammates.

For example, the middle linebacker focuses more on his fellow linebackers and the alignment of the defensive linemen. Also, he’s generally too far away from the defensive backs to yell to them. The safeties must coordinate their pass coverages after finding out what assistance the linebackers may offer in specific situations. They often have to use hand signals to convey their instructions in a noisy stadium.

Strong safety

Of the two types of safeties, the strong safety is generally bigger, stronger, and slower.

Coaches often refer to (and judge) their safeties as small linebackers. These players should be above-average tacklers and should have the ability to backpedal and quickly retreat in order to cover a specified area to defend the pass (which is called dropping into pass coverage). The strong safety normally aligns to the tight end side of the offensive formation (also known as the strong side, hence the name strong safety), and 99 percent of the time, his pass coverage responsibility is either the tight end or a running back who leaves the backfield.

Good strong safeties like Polamalu are superior against the run offense. Many strong safeties are merely adequate in pass coverage and below average when playing man-to-man pass defense. When you hear a television analyst inform viewers that the strong safety “did a great job of run support,” he means that the strong safety read his key (the tight end) and quickly determined that the play was a run rather than a pass. (Chapter 8 has more information on keys.)

Good strong safeties like Polamalu are superior against the run offense. Many strong safeties are merely adequate in pass coverage and below average when playing man-to-man pass defense. When you hear a television analyst inform viewers that the strong safety “did a great job of run support,” he means that the strong safety read his key (the tight end) and quickly determined that the play was a run rather than a pass. (Chapter 8 has more information on keys.)

The sole reason strong safeties are more involved with the run defense is because they line up closer to the line of scrimmage. Coaches believe that strong safeties can defend the run while also having the necessary speed and size to defend the tight end when he runs out on a pass pattern.

Free safety

The free safety (FS) is generally more athletic and less physical than the strong safety. He usually positions himself 12 to 15 yards deep and off the line of scrimmage, as shown in Figure 10-3. He serves the defense like a center fielder does a baseball team: He should have the speed to prevent the inside-the-park home run, which in football terms is the long touchdown pass. He also must have the speed and quickness to get a jump on any long pass that’s thrown in the gaps on the field. Ed Reed of the Baltimore Ravens is a quality free safety.

I would be remiss if I didn’t talk about Ronnie Lott, a Hall of Fame safety. What made Lott so special was that he could play either safety position. And he was so fast that he began his career as a cornerback. Never has a more intuitive player played in the secondary than Lott, who always seemed to know where the pass was headed.

I would be remiss if I didn’t talk about Ronnie Lott, a Hall of Fame safety. What made Lott so special was that he could play either safety position. And he was so fast that he began his career as a cornerback. Never has a more intuitive player played in the secondary than Lott, who always seemed to know where the pass was headed.

Being the final line of the defense against the long pass, the free safety must be capable of making instant and astute judgments. Some people say that an excellent free safety can read the quarterback’s eyes, meaning he knows where the quarterback is looking to throw the football. The free safety is the only defensive back who’s coached to watch the quarterback as his key. The quarterback directs him to where the ball is going.

A free safety must also be able to cover a wide receiver in man-to-man coverage, because many offenses today employ three wide receivers more than half the time. (The first two are covered by the cornerbacks.)

Nickel and dime backs

Some experts try to equate learning the nickel and dime defensive schemes with learning to speak Japanese. Not so! All it’s about is making change. When defensive coaches believe that the offense plans to throw the football, they replace bigger and slower linebackers with defensive backs. By substituting defensive backs for linebackers, defensive coaches ensure that faster players — who are more capable of running with receivers and making an interception — are on the field.

The fifth defensive back to enter the game is called the nickel back, and the sixth defensive back to enter is termed the dime back. The nickel term is easy to explain — five players equal five cents. The dime back position received its name because, in essence, two nickel backs are on the field at once. And, as you well know, two nickels equal a dime. However, each team has its own vernacular for the nickel and dime back positions. For example, the Raiders used to refer to their nickel back as the pirate. Regardless of the name, these players are generally the second-string cornerbacks. In other words, no team has a designated nickel back or dime back job.

The one downside of using a defensive scheme that includes nickel and dime backs is that you weaken your defense against the running game. For instance, many modern offenses opt to run the ball in what appear to be obvious passing situations because they believe that their powerful running backs have a size and strength advantage over the smaller defensive backs after the ball carrier breaks the line of scrimmage. Although defensive backs should be good tacklers, the prerequisite for the position is being able to defend pass receivers and tackle players who are more your size.

Substituting nickel and dime backs is part of a constant chess game played by opposing coaching staffs. Defensive coaches believe they’ve prepared for the occasional run and that these extra defensive backs give the defense more blitzing and coverage flexibility.

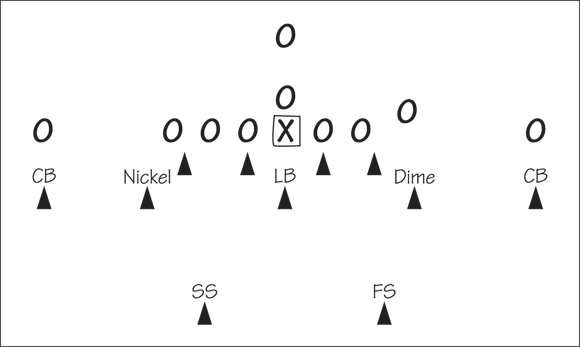

Figure 10-4 shows a common nickel/dime alignment that has a good success rate against the pass, especially when offenses are stuck in third-and-20 situations. This alignment enables teams to use many different defensive looks, which help to confuse the quarterback. But this scheme is poor against the run, so the defense has to remain alert to the possibility that the offense will fake a pass and run the ball instead.

Studying Secondary Tricks and Techniques

Being a defensive back is pretty scary. Often, the entire weight of the game is on your shoulders. One misstep in pass coverage or one missed tackle can lead to a touchdown. Also, a defensive back may be the only player between the ball carrier and the end zone. So this means that the defensive back has to be a good, smart tackler rather than an aggressive one.

When defensive backs line up, they rarely know whether the play will be a pass or a run. In a split second after the ball is snapped, they must determine the offense’s intentions and, if it’s a pass play, turn and run with one of the fastest players (the wide receiver) on the field. In the following sections, I introduce you to some of the tricks of their trade.

Doing a bump and run

The meaning of the term bump and run has been altered through the years. Thirty years ago, a cornerback could bump a receiver and then bump him again. Many cornerbacks held on for dear life, fearful the receiver would escape and catch a touchdown pass. Mel Blount, a Hall of Fame cornerback with the champion Pittsburgh Steelers of the 1970s, may have had the strongest hands of any defensive back. When he grabbed a receiver, even with one hand, the man could go nowhere; Blount would ride him out of the play. By ride I mean Blount (or any strong defensive back) could push the receiver away from his intended pass route. Most defensive backs tend to ride their receivers, if they can, toward the sidelines.

Blount perfected his hands-on technique so well that in 1978, the NFL’s Competition Committee (coaches, owners, and general managers who are appointed to study and make rule changes) rewrote the chuck rule, or what’s known as the bump in bump and run. Consequently, defensive backs are still allowed to hit receivers within 5 yards of the line of scrimmage, but beyond that, hitting a receiver is a penalty. The penalty for this illegal use of the hands gives the offense an automatic first down and 5 free yards (turn to Chapter 3 for the full scoop on penalties).

Today, you may see defensive backs with their hands on receivers beyond 5 yards. Sometimes the officials catch them, and sometimes they don’t. The intent remains the same: Defensive backs want to get in the faces of the receivers and chuck them or jam them (using both hands) as they come off the line of scrimmage. The idea is to disrupt the timing of the pass play by hitting the receiver in the chest with both hands, thereby forcing the receiver to take a bad step. Often, the defensive back pushes the receiver in order to redirect him. A defensive back generally knows which way a receiver wants to go. By bumping him to one side, the defensive back may force the receiver to alter his pass route.

Today, you may see defensive backs with their hands on receivers beyond 5 yards. Sometimes the officials catch them, and sometimes they don’t. The intent remains the same: Defensive backs want to get in the faces of the receivers and chuck them or jam them (using both hands) as they come off the line of scrimmage. The idea is to disrupt the timing of the pass play by hitting the receiver in the chest with both hands, thereby forcing the receiver to take a bad step. Often, the defensive back pushes the receiver in order to redirect him. A defensive back generally knows which way a receiver wants to go. By bumping him to one side, the defensive back may force the receiver to alter his pass route.

Staying with a receiver

After bumping or attempting to jam a receiver, a defensive back must be able to turn and run with the receiver. Sometimes, the defensive back (especially a cornerback) ends up chasing the receiver. When he needs to turn, the defensive back should make half-turns, rotating his upper body to the same side as the receiver. When the receiver turns to face the ball in the air, the defensive player should turn his body to the side of the receiver to which his arms are extended.

A defensive back must practice his footwork so he can take long strides when backpedaling away from the line of scrimmage while covering a receiver. When he turns, he should be able to take a long crossover step with his feet while keeping his upper body erect. This technique is difficult because the defensive back often has to move backward as quickly as the receiver runs forward. When he turns to meet the receiver and the pass, the defensive back should be running as fast as he can to maintain close contact with the receiver.

Stemming around

The term stemming around sounds foolish, and, in all honesty, defensive backs may look foolish while they’re stemming around. Well, at least they’re not standing around. Anyway, stemming describes the action of the defensive backs when they move around after appearing to be settled in their alignments prior to the offense’s snap of the ball. By stemming, they attempt to fool the quarterback and force him into making a bad decision about where to throw the football. This tactic is becoming quite popular in defensive football (all players can do it, but it’s most noticeable in defensive backs and linebackers) because it creates an uncertainty in the quarterback’s mind, thus disrupting his decision making.

The most successful stemming ploy by the secondary is to give the quarterback the impression that they’re playing man-to-man coverage when they’re really playing zone coverage. This ploy usually results in a poor read (an inaccurate interpretation of the defense) by the quarterback. A poor read can lead to a deflected pass, an incomplete pass, or an interception — the secondary’s ultimate goal.

Making a Mark: A Good Day in the Life of a Defensive Back

Quarterbacks and receivers tend to pick on defensive backs. Former Miami Dolphins quarterback Dan Marino passed them silly, and receivers like Andre Johnson and Larry Fitzgerald simply push them aside with their size and strength. The only way a defensive back can retaliate is to make a play.

This list shows some of the positive plays a defensive back can use to make his mark. The first three plays are reflected on the statistical sheet after the game; the rest just go into the receiver’s or quarterback’s memory bank. Of course, all tackles are recorded, but the ones I list here have a unique style of their own.

This list shows some of the positive plays a defensive back can use to make his mark. The first three plays are reflected on the statistical sheet after the game; the rest just go into the receiver’s or quarterback’s memory bank. Of course, all tackles are recorded, but the ones I list here have a unique style of their own.

-

Interception: The ultimate prize is an interception, which is when a defensive back picks off a pass intended for a receiver. An even bigger thrill is returning the catch for a defensive touchdown, which is called a pick-six (pick because the pass was picked off, and six because returning the catch for a touchdown scores six points).

-

Pass defensed: Pass defensed is a statistic that a defensive back achieves every time he deflects a pass or knocks the ball out of a receiver’s hands. You can also say that the defensive back broke up a pass. A pass defensed means an incompletion for the quarterback.

-

Forced fumble: A forced fumble is when a defensive back forces the ball away from a receiver after he gains possession of the ball. Defensive backs have been known to use both hands to pull the ball away from the receiver’s grasp. This play is also known as stripping the ball. Any defensive player can force a fumble, and forced fumbles can happen on running plays, too.

-

Knockout tackle: The knockout tackle is the ultimate tackle because it puts a wide receiver down for the count. Every safety in the league wants a knockout tackle; it’s a sign of intimidation. Defensive backs believe in protecting their (coverage) space and protecting it well. Cornerbacks want these hits, too, but many of them are satisfied with bringing an offensive player down any way they can.

-

Groundhog hit: A groundhog hit is a perfectly timed tackle on a receiver who’s leaping for the ball. Instead of aiming for the body, the defensive back goes for the feet, flipping the receiver headfirst into the ground.

The Problem of Pass Interference and Illegal Contact

When a receiver is running in a pass pattern and is more than five yards away from the line of scrimmage, a defensive player can’t push, shove, hold, or otherwise impede the progress of the receiver. If he does any of those things before the quarterback throws the ball, he’s called for either defensive holding or illegal contact. Both penalties result in five yards and an automatic first down for the offense.

When a pass is in the air, if a defensive player pushes, shoves, holds, or otherwise physically prevents an offensive receiver from moving his body or his arms in an attempt to catch the pass, he’s called for pass interference. Except for being ejected from a game, pass interference is the worst penalty in professional football for any member of the defensive team. Why? Because the number of yards that the defense is penalized is determined by where the penalty (or foul) is committed. So when the officials call pass interference against a defensive player on a pass attempt that travels 50 yards beyond the line of scrimmage, the penalty is 50 yards. The offensive team is given the ball and a first down at that spot on the field. If a defensive player is flagged (penalized) in the end zone, the offensive team is given the ball on the 1-yard line with a first down. (The offense is never awarded a touchdown on a pass interference penalty.)

This penalty is a judgment call, and you often see players from both sides arguing for or against a pass interference penalty. Officials don’t usually call pass interference when a defensive player, who also has a right to try to catch any ball, drives his body toward a pass, gets his hand or fingers on the ball, and then instantaneously makes physical contact with the receiver. The critical point is that the defensive player touched the ball a split second before colliding with the receiver. On these plays, the defensive back appears to be coming over the receiver’s shoulder to knock down the pass. Often, you can’t tell whether the official made the right call on these types of plays until you see them in a slow-motion replay on television. These plays (called bang-bang plays) occur very quickly on the field.

In recent years, the NFL has asked officials to pay special attention to defensive coverage of receivers. The result has been a tremendous increase in the number of holding, illegal contact, and pass interference penalties on the defense. Defensive players feel like they can’t even breathe heavily on receivers without getting flagged. Any sort of incidental bumping or pushing now warrants a flag.

Defensive backs (safeties and cornerbacks) now can’t afford to cover receivers tightly, so they have to give the receivers a bit of a cushion. This softer style has allowed offenses throughout the league to rack up huge passing numbers. Receivers are catching more passes and offenses are gaining more yards. If you like this style of football, the game is more exciting. But if you prefer low-scoring defensive struggles, you’re not a happy fan.

Examining the Two Types of Coverage (And Their Variations)

Football teams employ two types of pass coverage: man-to-man coverage and zone coverage. Both coverages have many variations and combinations, but the core of every coverage begins with either the man-to-man concept or a zone concept. I get you familiar with the core coverages first, and then I show you some of the variations.

Man-to-man coverage

Simply stated, man-to-man coverage is when any defensive back, or maybe even a linebacker, is assigned to cover a specific offensive player, such as a running back, tight end, or wide receiver. The defender must cover (stay with) this player all over the field until the play ends. His responsibility is to make sure the receiver doesn’t catch a pass. The most important rule of man-to-man coverage (which is also known as man coverage) is that the defensive back must keep his eyes on the player that he’s guarding or is responsible for watching. He’s allowed to take occasional peeks toward the quarterback, but he should never take his eyes off his man.

Here are the three main types of man-to-man coverage:

-

Man free: In this coverage, all defensive backs play man-to-man coverage except the free safety, who lines up or drops into an area and becomes a safety valve to prevent a long touchdown completion. This style of coverage is used when the defense blitzes, or rushes four or five players at the quarterback. So, man free is man-to-man coverage with one roaming free safety. Linebackers also cover running backs or even tight ends man-to-man.

-

Straight man: The free safety doesn’t serve as a safety valve in this alignment — or, as coaches say, no safety help is available. Each defender must know that he (alone) is responsible for the receiver he’s covering. The phrase “the player was stuck on an island” refers to a cornerback being isolated with an offensive receiver and having no chance of being rescued by another defensive back. This style of man-to-man coverage is generally used when the defense is blitzing or rushing a linebacker toward the backfield, hoping to sack the quarterback. Defenses use it depending on the strength and ability of their own personnel and the receiving talent of the offense they’re facing. So, straight man is pure man-to-man coverage with no roaming free safety.

-

Combo man: This category contains any number of combinations of man-to-man coverage. For example, when a team wants to double-team a great wide receiver (with two defensive backs), it runs a combo man defense. A great receiver is someone like Jerry Rice, who owns virtually every pass-receiving record in the history of pro football. The object of such a defense is to force the quarterback to throw the football to a less-talented receiver than someone like Rice (namely, anybody but him!).

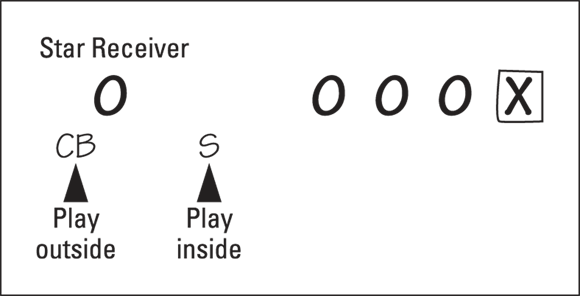

In Figure 10-5, the cornerback (CB) is responsible for the star receiver’s outside move, while the safety (S) is prepared in case the star receiver decides to run his route inside, or toward the middle of the field. A team’s pass defense may be vulnerable on the side of the field opposite where it’s double-teaming a receiver. Also, the pass defense may be vulnerable to a short pass on the same side of the field and underneath the double-team.

What’s fun about man-to-man coverages, especially for players, are the endless personnel matchup possibilities that they provide. Also, against an excellent throwing quarterback like the Denver Broncos’ Peyton Manning or the New Orleans Saints’ Drew Brees, these combinations create something of a chess match between the quarterback and the defensive secondary.

Zone coverage

In zone coverage, the defensive backs and linebackers drop into areas on the field and protect those zones against any receivers who enter them. The biggest difference between zone coverage and man-to-man coverage is that in the latter coverage, a defender is concerned only about the player he’s covering. In virtually all zone coverages, two defensive backs play deep (12 to 15 yards off the line of scrimmage) and align near the hash marks.

In a zone coverage, each defensive back is aware of the receivers in his area, but his major concentration is on the quarterback and reacting to the quarterback’s arm motion and the ball in flight. Coaches employ zone coverage against teams that love to run the football because it allows them to better position themselves to defend the run. Other teams use zone coverage when the talent level of their secondary personnel is average and inferior to that of the offensive personnel they’re facing.

For defensive backs, zone coverage is about sensing what the offense is attempting to accomplish against the defense. Also, in zone coverage, each defensive player reacts when the ball is in the air, whereas in man-to-man coverage, he simply plays the receiver.

The simplest way to recognize a zone defense is to observe how many defenders line up deep in the secondary. If two or more defensive players are aligned deep (12 to 15 yards off the line of scrimmage), the defense is in a zone.

The simplest way to recognize a zone defense is to observe how many defenders line up deep in the secondary. If two or more defensive players are aligned deep (12 to 15 yards off the line of scrimmage), the defense is in a zone.

Eight men in the box

I’m sure you’ve heard television commentators mention the term eight men in the box. They aren’t talking about a sandbox, and they aren’t discussing a new pass coverage. Instead, they’re talking about a setup that enables a team to defend the run more effectively when it has a strong secondary.

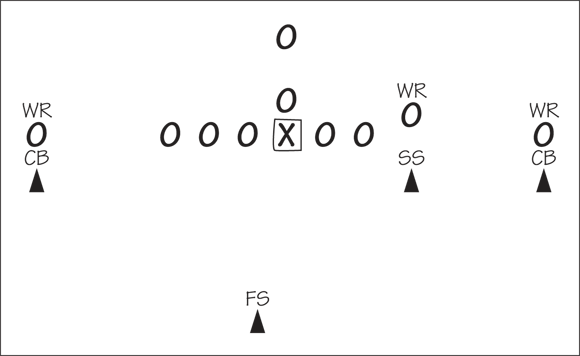

The box is the imaginary area near the line of scrimmage where the defensive linemen and linebackers line up prior to the offense putting the ball into play. Usually, a team puts seven defenders, known as the front seven, in that box. But a team can put an eighth man — the strong safety (SS) — in the box, as shown in Figure 10-6, if it has two outstanding cornerbacks (CB) who can cover wide receivers (WR) man to man.

So how does a talented pair of cornerbacks drastically improve a team’s defense against the run? By allowing the defense to play an extra (eighth) man in the box, where the defense has to deal with the runner. By placing eight defenders against six blockers — five offensive linemen and a tight end — the odds are pretty good that the running back will have trouble finding open territory. And when a team has talented cornerbacks who can defend the pass effectively, the defensive linemen and linebackers perform with the utmost confidence. They know that they can attack without worrying about their pass coverage responsibilities.

The Nickel 40 defense

By definition, the Nickel 40 defense is strictly a pass defense that can employ either a linebacker or another defensive back as the sixth player in pass coverage. It’s a substituted defense (one that generally isn’t used on every down) by skill and ability level. A defensive team wants to put its four best pass-rushers on the line of scrimmage, with one linebacker and six defensive backs.

The sixth, or dime back (DB), position can end up being a defensive back as well as a linebacker at times. In this alignment, the linebacker aligns in the middle about 5 yards away from the line of scrimmage (see Figure 10-7). He should be one of the team’s fastest linebackers as well as a good tackler. Most teams use four defensive backs near the line of scrimmage with two safeties playing well off the ball, toward the middle of the field near the hash marks.

The object of the Nickel 40 is to pressure the quarterback, hoping to either sack or harass him. Teams use their four best pass-rushers on the field in this alignment, and these four players will most likely be opposed by only five offensive linemen. Defenses use a Nickel 40 defense only when the offense uses three or more receivers in its alignment.

The object of the Nickel 40 is to pressure the quarterback, hoping to either sack or harass him. Teams use their four best pass-rushers on the field in this alignment, and these four players will most likely be opposed by only five offensive linemen. Defenses use a Nickel 40 defense only when the offense uses three or more receivers in its alignment.

From this defensive look, the pass-rushers may stem or stunt (move about on the line of scrimmage), trying to apply pressure by using their best linemen against the offense’s weakest blockers. Defenses also have been known to blitz the quarterback with one of the defensive backs or a linebacker in order to overwhelm the offensive blocking scheme. The defensive pass coverage in the secondary can be a mixture of man-to-man and zone alignments.

The Nickel 40 is a good defense against an offense that’s fond of play-action passes (when the quarterback fakes a handoff to a running back, keeps the ball, and then attempts a pass; see Chapter 8 for more on these) or against an offense that likes to substitute a lot of receivers into the game. I’m talking about offenses that use formations that employ four wide receivers rather than the customary two wide receivers. The Nickel 40 defense, with faster personnel, can compensate and deal with an offense that prefers to always have a player in motion prior to the snap of the ball. It’s also adept against other unusual formations.

Meeting the secondary’s members: Cornerbacks, safeties, and nickel and dime backs

Meeting the secondary’s members: Cornerbacks, safeties, and nickel and dime backs Getting to know the tricks of the secondary trade

Getting to know the tricks of the secondary trade Recognizing the difference between zone and man-to-man coverages

Recognizing the difference between zone and man-to-man coverages Understanding the eight men in a box and Nickel 40 coverage variations

Understanding the eight men in a box and Nickel 40 coverage variations Be aware that a majority of big offensive plays (gains of 25 yards or more) and touchdowns come from the offense’s ability to execute the passing game. Therefore, on the defensive side of the ball, a great deal of attention on television is devoted to the secondary. Often, a defensive back is in proper position or has good coverage technique, but the offensive receiver still catches the pass. Other times, the secondary player is out of position, failing to execute his assignment, or is physically beaten by a better athlete. If you know the difference and what to look for, you’ll be regarded as an expert.

Be aware that a majority of big offensive plays (gains of 25 yards or more) and touchdowns come from the offense’s ability to execute the passing game. Therefore, on the defensive side of the ball, a great deal of attention on television is devoted to the secondary. Often, a defensive back is in proper position or has good coverage technique, but the offensive receiver still catches the pass. Other times, the secondary player is out of position, failing to execute his assignment, or is physically beaten by a better athlete. If you know the difference and what to look for, you’ll be regarded as an expert.

I would be remiss if I didn’t talk about Ronnie Lott, a Hall of Fame safety. What made Lott so special was that he could play either safety position. And he was so fast that he began his career as a cornerback. Never has a more intuitive player played in the secondary than Lott, who always seemed to know where the pass was headed.

I would be remiss if I didn’t talk about Ronnie Lott, a Hall of Fame safety. What made Lott so special was that he could play either safety position. And he was so fast that he began his career as a cornerback. Never has a more intuitive player played in the secondary than Lott, who always seemed to know where the pass was headed.

This list shows some of the positive plays a defensive back can use to make his mark. The first three plays are reflected on the statistical sheet after the game; the rest just go into the receiver’s or quarterback’s memory bank. Of course, all tackles are recorded, but the ones I list here have a unique style of their own.

This list shows some of the positive plays a defensive back can use to make his mark. The first three plays are reflected on the statistical sheet after the game; the rest just go into the receiver’s or quarterback’s memory bank. Of course, all tackles are recorded, but the ones I list here have a unique style of their own.