Chapter 8

Examining Offensive Plays and Strategies

In This Chapter

Running specialized pass offenses and exploring new offensive formations

Running specialized pass offenses and exploring new offensive formations

Defeating different defensive fronts

Defeating different defensive fronts

Discovering how to gain yards

Discovering how to gain yards

Deciding when to gamble on offense

Deciding when to gamble on offense

Choosing a goal-line offense

Choosing a goal-line offense

When I played defense, I knew that the offensive coaches were trying to get into my head and into the minds of my defensive buddies. When calling a specific play, the offensive coaches wanted to not only beat us but also make us look foolish. This chapter unmasks some of the tricky tactics those offensive geniuses come up with when they’re burning the midnight oil studying defensive tendencies.

When football teams decide which play or formation to use, they base the decision on the personnel matchups they want. Coaches study the opposition and examine hours of film hoping to find the weak links in the opposing defense. No defensive team has 11 great players. So, the offense’s design is to move away from the opposition’s strengths and attack the weaknesses.

Here’s another thing you should know about offensive strategy: No perfect play exists for every occasion. In strategy sessions prior to a game, a play may look like it will result in a long gain, but in reality it may not succeed for various reasons. It may fail because someone on the offensive team doesn’t execute or because a defensive player simply anticipates correctly and makes a great play. Things happen!

Here’s another thing you should know about offensive strategy: No perfect play exists for every occasion. In strategy sessions prior to a game, a play may look like it will result in a long gain, but in reality it may not succeed for various reasons. It may fail because someone on the offensive team doesn’t execute or because a defensive player simply anticipates correctly and makes a great play. Things happen!

In this chapter, I explain the basic offensive approaches to the game and walk you through some particular plays and overall schemes. Then I discuss which offensive plays or formations work well against particular defenses and in specific situations. When does a quarterback sneak work? When is play-action passing ideal? What goal-line run plays really work? What does a team do on third-and-long? This chapter has answers for all these questions and a whole lot more.

Offense Begins with Players

The first thing you should know about offense is that players win games — schemes, formations, and trick plays don’t. If a player doesn’t execute, none of the decisions that the coaches made will work. And I’m not talking merely from the point of view of an ex-player; coaches, owners, and scouts all know that this is true.

The opposite scenario applies, too: A play designed to gain the offense only a couple of yards can turn into a score unexpectedly if a defensive player misses a tackle or turns the wrong way or if an offensive player makes a spectacular move. Having been a defensive player, I know that we sometimes had players placed in the right situations to defend a play perfectly, but the play still succeeded because of an offensive player’s outstanding effort.

And look at the size of today’s offensive players — who can stop them? So many runners and receivers weigh 200 pounds or more, and they all can run 40 yards in 4.5 seconds or faster. (The 40-yard dash is a common test that teams use to measure players’ talents.) Peyton Manning, quarterback of the Denver Broncos, weighs 230 pounds and is 6 feet 5 inches tall. Quarterback Ben Roethlisberger of the Pittsburgh Steelers is 6 feet 5 inches tall and weighs 241 pounds.

And it isn’t just the quarterbacks, runners, and receivers who are growing in size. Some teams have 325-pound offensive linemen who can run 40 yards in 5 seconds flat, and some are as agile as men half their size. They’re as big as the defensive linemen, therefore giving the skilled players on offense an opportunity to succeed. Every great ball carrier will tell you that he can’t gain his 1,000 yards a season without a very good offensive line.

Zeroing in on Specialized Pass Offenses

Few passes travel more than 10 or 12 yards. I’m sure you’ve heard about the bomb — a reference to a long pass — but those 35- to 40-yard or longer pass plays are pretty rare, thanks to the modern pass offenses that are run in the NFL and college football. As a fan, you should be aware of two types of pass offenses, which I describe in the sections that follow.

West Coast offense

Currently, Aaron Rodgers and a handful of other NFL quarterbacks operate a short, ball-control passing game called the West Coast offense. It got this name because it was developed by coach Bill Walsh, who directed the San Francisco 49ers to three Super Bowls. The West Coast offense’s popularity spread throughout the NFL as Walsh disciples such as Mike Holmgren, Mike Shanahan, and Jon Gruden began using it. Many college teams use variations of this offense, depending on the talent of their receivers.

The West Coast offense uses all the offense’s personnel in the passing game, as opposed to an I-formation team that’s structured to run the ball and rarely throws to the running backs. (I tell you all about the I formation in Chapter 6.) Rather than running long routes downfield, the wide receivers run quick slants or square-out patterns toward the sidelines, hoping to receive the ball quickly and gain extra yards after the catch. The receivers run a lot of crossing routes, meaning they run from left to right or right to left in front of the quarterback, maybe 10 yards away. Crossing routes are effective because they disrupt many defensive secondary coverages.

If a running back is good at catching the ball, he becomes a prime receiver in the West Coast offense. This offense also uses a tight end on deeper routes than most other offenses. Because the offense has so many potential pass catchers (two receivers and two running backs or three receivers and one running back) on a typical pass play, the tight end can often find open areas after he crosses the line of scrimmage. The defensive players in the secondary tend to focus their attention on the wide receivers. The West Coast offense incorporates the tight end into most pass plays, so that player must be an above-average receiver.

The premise of the West Coast offense is to maintain possession of the ball. Although it has quick-strike scoring possibilities, it’s designed to keep offensive drives alive by passing rather than running the ball. One of the basic theories of this offense is as follows: If the defense is suspecting a run, pass the ball to the running back instead.

The premise of the West Coast offense is to maintain possession of the ball. Although it has quick-strike scoring possibilities, it’s designed to keep offensive drives alive by passing rather than running the ball. One of the basic theories of this offense is as follows: If the defense is suspecting a run, pass the ball to the running back instead.

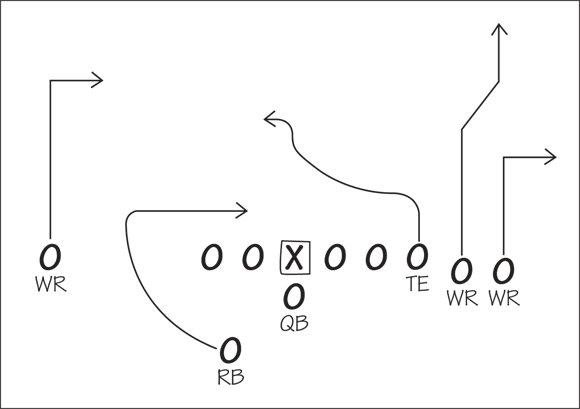

Shotgun offense

For obvious passing downs, some teams use the shotgun offense. In the shotgun, the quarterback (QB) lines up 5 to 7 yards behind the center and receives a long snap, as shown in Figure 8-1. The pass plays used in this offense are identical to those used when the quarterback is under center; offenses use the shotgun simply to allow the quarterback more time to visualize the defense, particularly the secondary’s alignment. On an obvious passing down, nothing can be gained by keeping the quarterback under center. Why have him spend time dropping back to pass when he can receive a long snap and be ready to throw?

The QB is positioned 5 to 7 yards behind the center in the shotgun offense.To run this offense, you want a quarterback who’s quick with his decisions and also able to run with the football if the defense’s actions make it possible for him to gain yardage by carrying the ball himself.

The best shotgun quarterback I ever saw was John Elway of the Denver Broncos. Jim Kelly of the Buffalo Bills truly excelled in the shotgun, too. Elway and Kelly seemed more comfortable and confident in this formation than other quarterbacks.

The best shotgun quarterback I ever saw was John Elway of the Denver Broncos. Jim Kelly of the Buffalo Bills truly excelled in the shotgun, too. Elway and Kelly seemed more comfortable and confident in this formation than other quarterbacks.

From a defensive lineman’s viewpoint, the shotgun is okay because you don’t have to concentrate on defending the run; you know that the offense is going to pass. In other formations, a defender has to be prepared for both possibilities: run or pass. He has to think before reacting. When facing the shotgun, a defensive lineman has only one mission: to get to the quarterback as fast as he can.

Looking at Some Newfangled Offenses

One of the great pleasures of following the game of football is seeing it evolve over time. Coaches are always trying innovative new schemes on offense and defense to catch their opponents off guard. Consequently, the game keeps changing. If you watch a football game from years past (you can watch these games on DVD, on ESPN Classic, and at www.nflnetwork.com/nflnetwork), the first thing you notice is how different the game is now, especially on offense. The previous century saw offenses use and abandon these formations: the flying wedge, the single wing, the wing T, the Notre Dame Box, and the wishbone. Recent years have seen three new offensive formations: the wildcat, the spread, and the pistol. I describe them in the next sections.

The wildcat

The wildcat formation is unique in football because, when an offense runs the wildcat, the quarterback isn’t on the field. His place is taken by a running back or sometimes a wide receiver, who takes the snap shotgun-style from 5 to 7 yards behind the center. The running back or receiver then runs the ball (or sometimes hands it to another running back).

The wildcat offers a couple advantages to the offense. Without a quarterback on the field, the offense has an extra blocker to help the runner advance the ball. And because the halfback takes the snap from center, the offense wastes no time handing off the ball. The runner can make his move as soon as the ball is snapped. Moreover, by starting from 5 to 7 yards behind the offensive line, the runner has a good field of vision. He can better see where the defenders are and where his offensive line has busted a hole in the defense for him to run through.

In the 2008 season, the Miami Dolphins ran the wildcat with talented running backs Ricky Williams and Ronnie Brown, and they won 11 games. But for the most part the wildcat is used sparingly in the NFL and in college. If a team runs the wildcat, it frequently does so only when it needs 2 to 3 yards to get a first down. The wildcat is a one-dimensional offensive formation. Most of the advantages of running the wildcat are cancelled out by the fact that the defense can focus on the run — it doesn’t have to defend against a player who is good at passing the ball — when it sees its opponent lining up in the wildcat.

The spread

The spread gets its name because, in this formation, the offense spreads out across the width of the field, causing the defensive players to spread out accordingly. The quarterback takes the snap shotgun-style, after which he can run the ball, pass it, or hand it off, often to a runner who’s going in motion across the backfield. The idea behind the spread is to open up the field and create more offensive opportunities — more seams for runners to attack and more space in which receivers can get open.

The spread is used far more often in college football than in the pro game for a very important reason: In the spread, the quarterback runs as well as passes the ball, and in the NFL, where players are faster and bigger, and where the quarterback is a very valuable commodity, teams don’t want to risk an injury to the quarterback by allowing him to run the ball.

Still, with all its option and misdirection plays, the spread formation makes for very exciting football, and many college teams have found success with the spread. The 2011 Bowl Championship Series (BCS) championship game (see Chapter 16 for information about the BCS) featured two teams that ran the spread offense — the Oregon Ducks and the Auburn Tigers.

The pistol

The pistol, like the wildcat and the spread formation, is run from a shotgun snap. The quarterback lines up 4 yards behind center, and a running back lines up 3 yards behind the quarterback. The pistol combines the advantages of the shotgun formation and the I formation. Lining up 4 yards behind center gives the quarterback a better view of the defense and allows him the opportunity to throw quick passes without having to drop back before passing the ball. The running back, meanwhile, also gets a good look at the defense, because he’s even farther behind the line of scrimmage than the quarterback. Like the spread, the pistol requires a quarterback who can run as well as pass. Running quarterbacks, however, take a lot more hits than pocket quarterbacks, and injuries are often a factor over the course of a season. Colin Kaepernick of the San Francisco 49ers and Robert Griffin III of the Washington Redskins both have had success running plays from the pistol formation.

Beating a Defense

One of the primary factors that helps a coach decide what offense to run and what plays to call is how the defense sets up. Various defenses call for different strategies to beat them. The following sections describe some defenses and the offensive plays or formations that may work against those defensive schemes. For more information about any of these defenses, flip to Chapter 11.

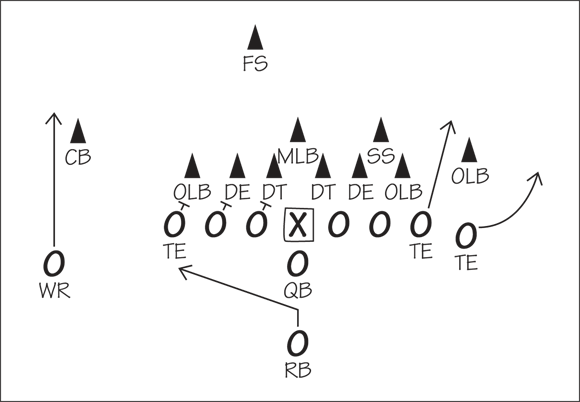

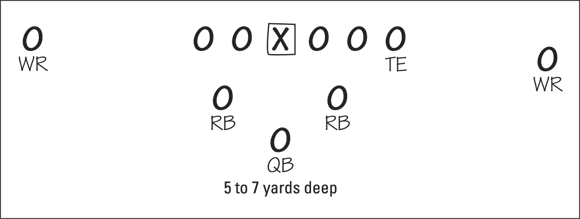

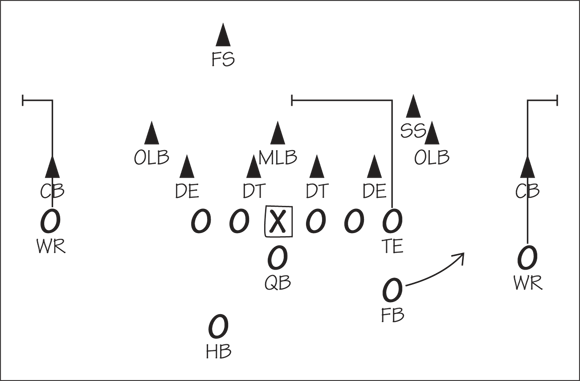

Battling a 3-4 front

When facing a 3-4 front (three down linemen and four linebackers), the offense’s best strategy is to run weak side, or away from the tight end (which is always the strong side of any offensive formation). One possible running play is called the weak-side lead. With this play, the defensive end (DE) usually attempts to control and push the offensive tackle (LT) inside toward the center of the line, leaving the linebacker behind him (OLB) to defend a lot of open area. The offense is in the I formation, and the fullback (FB) runs to the weak side and blocks the linebacker, shoving him inside. The left offensive tackle allows the defensive end to push him a little, letting the defender believe that he’s controlling the play. However, the offensive lineman then grabs the defender, containing him, and moves him out of the way to the right. The ball carrier should have a clear running lane after he hits the line of scrimmage. Figure 8-2 diagrams this play.

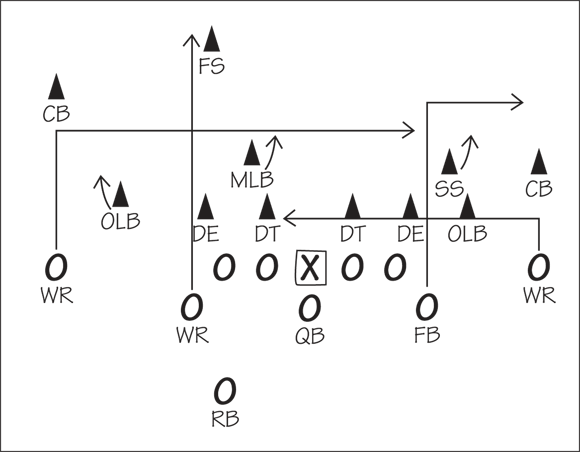

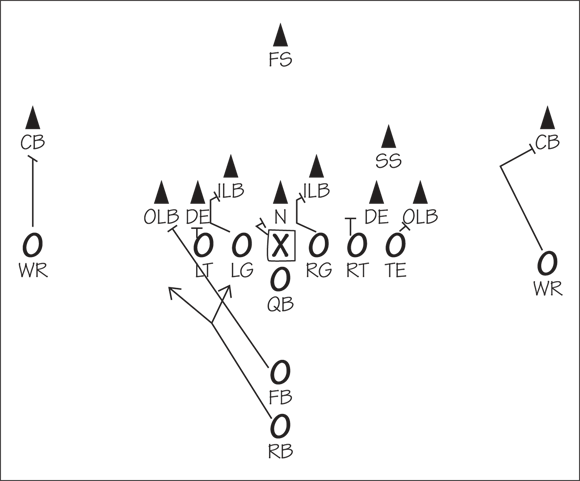

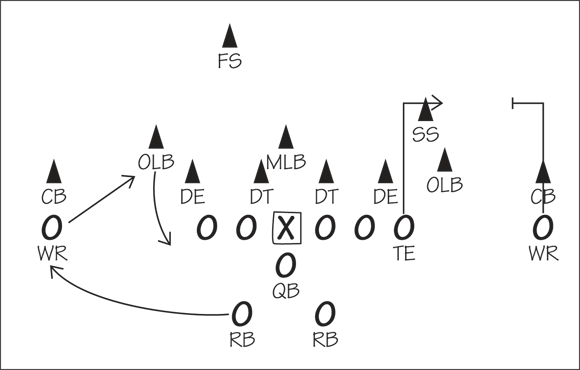

Running against a 4-3 front

An offense can attack a 4-3 front (four down linemen, three linebackers) in many different ways, but one common strategy is to attack what coaches call the bubble side (the defensive side where the two linebackers are positioned). Remember, the 4-3 defense employs both over and under slants that the four-man defensive line uses. Overs and unders are basically the alignments of defensive linemen to one particular side of the offensive center (see Chapter 11 for further details). When the defensive front lines up in an under look, the offense attacks the bubble.

The offensive play shown in Figure 8-3 is called a delay draw to the strong side (the tight end side) of the offensive formation. When the defense is positioned like this, three defensive linemen line up over the center, left guard, and left tackle. These offensive linemen are also called the weak-side guard and tackle. This defensive alignment leaves only one lineman and two smaller linebackers (DE, ILB, and OLB) to defend the strong side of the offense’s I formation (turn to Chapter 6 for the scoop on this formation).

On the delay draw, the right guard (RG) blocks down on the defensive nose tackle (N), and the fullback (FB) runs into the hole and blocks the front-side linebacker (ILB). The right tackle (RT) blocks the defensive end (DE), keeping him out of the middle, and the tight end (TE) blocks and contains the outside linebacker (OLB). This approach is known as running at the defense’s weakest point. When the ball carrier reaches the line of scrimmage, he should find open space between the offense’s right guard and right tackle.

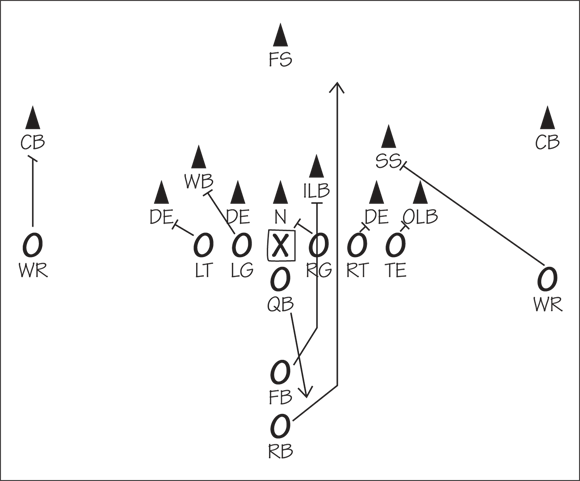

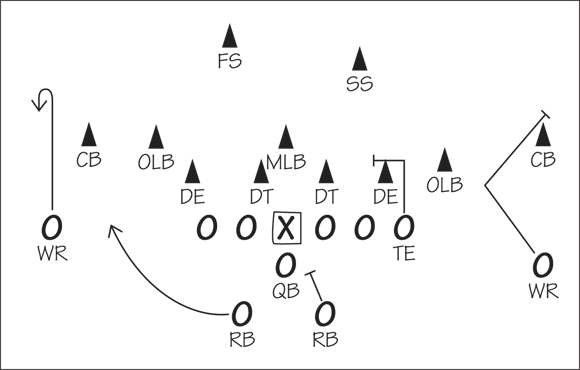

Defeating the four-across defense

In the four-across defense, the defense plays all four secondary players deep, about 12 yards off the line of scrimmage. To beat this defense, the offense wants to have two wide receivers (WR) run comeback routes, have the tight end (TE) run a 16-yard in route, and have the two backs (RB) swing out to the right and left. The running back to the quarterback’s left side should run more of a looping pass pattern. The quarterback (QB) throws the ball to the wide receiver on the left, as shown in Figure 8-4.

The quarterback throws to his left because the ball is placed on the left hash mark, which is the short side of the field. Throwing a 15-yard comeback pass to his left is much easier than throwing a 15-yard comeback to the right, or the wide side of the field. The pass to the wide side would have to travel much farther, almost 42 yards, as opposed to just 15 yards. From the left hash mark to the numbers on the right side of the field, the distance is more than 19 yards. And the comeback to the right is always thrown beyond those numbers (10, 20, 30, 40), going down the length of the field.

The quarterback throws to his left because the ball is placed on the left hash mark, which is the short side of the field. Throwing a 15-yard comeback pass to his left is much easier than throwing a 15-yard comeback to the right, or the wide side of the field. The pass to the wide side would have to travel much farther, almost 42 yards, as opposed to just 15 yards. From the left hash mark to the numbers on the right side of the field, the distance is more than 19 yards. And the comeback to the right is always thrown beyond those numbers (10, 20, 30, 40), going down the length of the field.

If the defense senses that the quarterback is going to throw to the wide receiver on the left side and then decides to drop a linebacker into underneath coverage, hoping to intercept, the quarterback can’t throw that pass. By underneath, I mean that the linebacker is dropping back to defend the pass, but safeties are still positioned beyond him. Hence, the linebacker is underneath the safeties. Instead, the quarterback throws to the running back on the same side. The quarterback simply keys (watches) the linebacker. If the linebacker drops into coverage, the quarterback throws to the running back because he won’t be covered. If the linebacker takes the running back, the quarterback throws to the receiver.

Beating press coverage

Press coverage is when the defensive team has its two cornerbacks on the line of scrimmage, covering the outside receivers man-to-man. One tactic against this defense is to throw to the tight end (TE), who runs to the middle of the field, as shown in Figure 8-5. Another option is to throw to the running back (RB), who’s swinging out to the left. The wide receivers (WR), who are being pressed, run in the opposite direction, away from the area in which either the tight end or the running back is headed, as shown in Figure 8-6.

Passing against a zone coverage

When I say “passing against a zone coverage,” I’m talking about a defensive secondary that’s playing zone — meaning the cornerbacks are playing off the line of scrimmage. They aren’t in press coverage. The best pass against a zone coverage is the curl, and the best time to use it is on first-and-10. A receiver (WR) runs 10 to 12 yards and simply curls, or hooks back, toward the quarterback (QB), as shown in Figure 8-7. He usually curls to his left and attempts to run his route deep enough to gain a first down. The coverage should be soft enough (meaning the defensive back, CB, is playing 5 to 7 yards off the receiver) on these routes that the receiver’s size shouldn’t matter. However, against a man-to-man scheme, a smaller receiver may be ineffective when running patterns against a taller, stronger defensive back.

Selecting an offense versus a zone blitz

Pittsburgh Steelers defensive coordinator Dick LeBeau invented the zone blitz in the late 1980s, giving his team the nickname “Blitzburgh” (see Chapter 11 for details on the zone blitz). Sustaining a running offense is difficult against teams that run a zone blitz. Some offenses have had success running against zone blitz defenses, but I don’t think you can beat them consistently by running the ball.

When facing a defense that blitzes a lot off the corner (linebackers or safeties coming from either wide side of the line of scrimmage against your offensive tackles), the offense should align with two tight ends in order to help pass-protect. To beat a zone blitz with a passing attack, the offense must find its opponent’s weakest defender in the passing game (be that cornerback, safety, or linebacker).

The quarterback must throw to the side opposite where the defense is overloaded (has more players). For example, if the defense positions four players to the quarterback’s left, as shown in Figure 8-8, the quarterback should throw to his right. But the offense must still block the side from which the defense is attacking.

Throwing the post versus blitzing teams

Most defenses protect against quarterbacks attempting to throw the post route, which is when a receiver fakes to the outside and then runs straight down the field toward the goalpost. The quarterback lines up the throw by focusing on the hash marks. When he releases the ball, he tries to lead the receiver, or throw the ball slightly in front of him, so that the pass drops to the receiver over his shoulder. That way, if a defensive player is chasing the receiver, the defender shouldn’t be able to intercept the pass.

The deep post doesn’t really work well against zone blitz defenses. Why? Because these teams rarely leave the post open. They defend it pretty well.

However, other teams that blitz from a basic 4-3 defense may use a safety to blitz the quarterback. When a team uses a safety to blitz, usually the defense is vulnerable in the center of the field, where both safeties should be. Still, very few teams leave the deep post wide open because it can give the offense a quick six points.

Wearing out a defense with the no-huddle offense

In need of a score late in a game, every team runs a no-huddle offense in an attempt to move down the field quickly. (See “Doing the two-minute drill” later in this chapter for more info on late-game tactics.) In essence, by quickly running plays without pausing to huddle, the offense prevents the defense from substituting players and changing its scheme. The quick pace of play can tire out a defense, leaving it vulnerable to a score.

A handful of teams with elite quarterbacks — the New England Patriots with Tom Brady, the Denver Broncos with Peyton Manning, the New Orleans Saints with Drew Brees, and the Green Bay Packers with Aaron Rodgers — run their two-minute, or no-huddle, offense, throughout the game.

Gaining Better Field Position

Of course, scoring is always an offense’s ultimate goal, but to score, you have to move down the field toward your opponent’s end zone. In the next sections, I describe the various strategies for gaining yards and, consequently, a better field position.

Throwing a field position pass

When offenses face third down and more than 6 yards, which is known as third-and-long, the safest play is for the quarterback to throw to a running back who’s underneath the coverage of the defensive secondary. Why? Because in such situations, the defensive secondary, which is aligned well off the line of scrimmage, is always instructed to allow the receiver to catch the ball and then come up and tackle him, preventing a first down.

Early in the game, when your offense is down by ten or fewer points, you want to run a safe play on third-and-long, knowing that you’ll probably end up punting the ball. In other words, your offense is raising its white flag and giving up. That’s why this pass to the running back is called a field position pass. Maybe the back will get lucky, break a bunch of tackles, and gain a first down, but basically you’re playing for field position. The odds of beating a good defensive team under third-and-long conditions are pretty slim.

Opting for possession passes

Most of the time, a possession pass is a short throw, between 8 and 10 yards, to either a running back or a tight end. The intent isn’t necessarily to gain a first down but to maintain possession of the ball while gaining yardage. Often, teams call possession passes several times in a short period to help the quarterback complete some easy passes and build his confidence.

If the quarterback wants to throw a possession pass to a wide receiver and the defensive secondary is playing off the line of scrimmage, his best option is to throw a 5-yard hitch. A 5-yard hitch is when the receiver runs up the field 5 yards, stops, and then turns back so that he’s facing the quarterback. When the receiver turns, the ball should almost be in his hands. Coaches call these throws when the quarterback has thrown some incompletions, giving him a chance to calm down and complete a few easy passes.

Moving downfield with play-action passes

In a play-action pass, the quarterback fakes a handoff to a running back and then drops back 4 more yards and throws the football. The fake to the running back usually causes the linebackers and defensive backs to hesitate and stop coming forward after they realize that it isn’t a running play. They stop because they know they must retreat and defend their pass responsibility areas.

If neither team has scored and the offense is on its own 20-yard line, that’s a perfect time to throw the football. Some conservative offensive teams run play-action only in short-yardage situations (for example, second down and 3 yards to go). But play-action works whenever the defense places its strong safety near the line of scrimmage, wanting to stuff the run. Because the defensive pass coverage is likely to be soft, the offense has a good opportunity to throw the ball. And the defense shouldn’t be blitzing, which in turn gives the quarterback plenty of time to throw.

Surveying Offenses for Sticky Situations

One of the biggest challenges of being a coach — or a quarterback, for that matter — is to lead your team out of the sticky situations that arise. This section explains some of the strategies that offenses use to gain the necessary yardage for a first down, move downfield with little time left on the clock, and more.

Deciding whether to gamble on fourth-and-1

The game is tied, and on fourth-and-1 you have a decision to make: Should your team kick a field goal or go for the first down and maintain possession, hoping to end your offensive possession with a touchdown?

For most coaches, the decision depends on the time of the game and the team they’re playing. If a team is on the road against a solid opponent, one that has beaten the team consistently in the past, most coaches elect to kick a field goal. In the NFL, some teams are especially difficult to beat at home. For example, the New England Patriots won 21 consecutive home games (including playoff games) in the 2002 through 2005 seasons. The thought process is that any lead, even a small one, is better than risking none at all against such a team when you’re on the road. So, at Gillette Stadium, where the Patriots play, you kick the field goal and take your three points.

A coach’s strategy may change drastically when his team is playing the same opponent in its own stadium. If I’m playing in my stadium and I’m leading 17–7 in the fourth quarter, I may go for it on fourth-and-1 — especially if we’re inside the other team’s 20-yard line. I may let my team take a shot, especially if the offense hasn’t been very effective. If my team doesn’t make the first down, the other team has to go more than 80 yards to score, and it has to score twice to beat me. You’d rather be in the other team’s territory when you gamble. Never gamble in your own territory — it could cost your team three points or a touchdown.

A coach’s strategy may change drastically when his team is playing the same opponent in its own stadium. If I’m playing in my stadium and I’m leading 17–7 in the fourth quarter, I may go for it on fourth-and-1 — especially if we’re inside the other team’s 20-yard line. I may let my team take a shot, especially if the offense hasn’t been very effective. If my team doesn’t make the first down, the other team has to go more than 80 yards to score, and it has to score twice to beat me. You’d rather be in the other team’s territory when you gamble. Never gamble in your own territory — it could cost your team three points or a touchdown.

The toughest area in which to make a decision is between your opponent’s 35- and 40-yard lines — a distance that may be too far for your field goal kicker but too close to punt. If your punter kicks the ball into the end zone, for example, your opponent begins possession on the 20-yard line, giving you a mere 15-yard gain in field position. When you’re making the decision whether to kick or punt in this 35- to 40-yard line area, you may as well toss a coin.

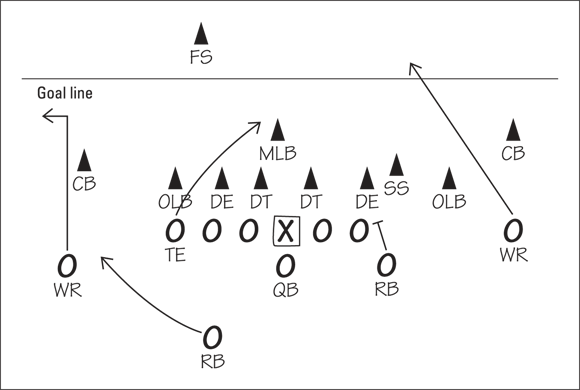

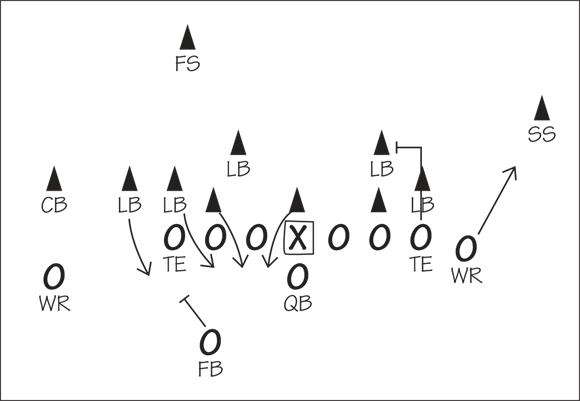

Making a first down on a fourth-down gamble

It’s fourth down and 1 yard to go for a first down, and your offense just crossed midfield. You want to gamble, believing that your offense can gain enough yards for a first down. The best play to call in this situation is a run off the tackle and the tight end on the left side of the formation, as shown in Figure 8-9.

Your offense has three tight ends in the game: the standard short-yardage personnel. These players always practice running a few specific plays during the week. Your offense knows that the defense plans to plug up the middle; they don’t want an interior running play to beat them. They’ll defend that area. To fool the defense and maximize the offense’s chance to succeed, the offensive alignment puts two tight ends to the right, hoping the defense will react to the formation and slant its personnel to that side because it believes that the play is centered there. With the defense slanted to prevent a run to the right, the offense runs to the left.

Running a quarterback sneak

The quarterback sneak is one of the oldest plays in the book. But it isn’t that simple to execute, and it doesn’t always succeed. The play is designed for the quarterback to run behind one of his guards, using the guard as his principal blocker. Teams run the quarterback sneak when they need less than a full yard, sometimes only a few inches, for a first down.

To be successful with the sneak, the quarterback delays for a moment and determines the angle the defensive linemen are coming from. Then he dives headfirst, pushing his shoulders into the crack behind whichever guard (the right or left side) is called in the huddle.

The quarterback wants to run at the weakest defensive tackle. For example, you don’t want to run at the Seattle Seahawks’ Kevin Williams; you want to run at the other tackle. If the Baltimore Ravens’ Haloti Ngata is aligned over your right guard, you want to sneak over your left guard. You make the sneak work by having your center and guard double-team the defensive tackle (or whoever’s playing in this gap opposite the two offensive linemen). These two blockers must move the defensive tackle or the defender in that gap.

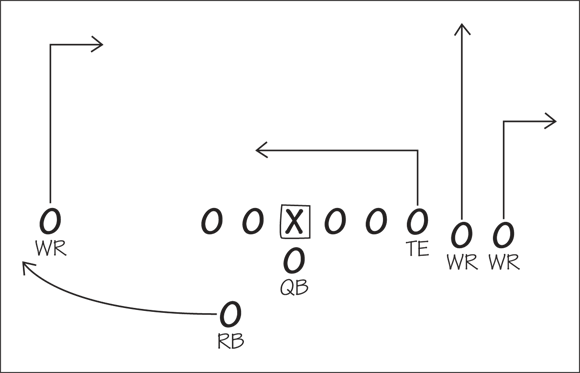

Doing the two-minute drill

Your team has two minutes left in the game to drive 70 yards for a score. You must score a touchdown (and successfully kick the extra point) to tie the game. As an offensive coach, you’re hoping the defense decides to play a prevent defense, which means they use seven players in pass coverage while rushing only four linemen or linebackers at the quarterback. When a defense plays a prevent defense, you may want to run the ball because the running back has plenty of room to run after he crosses the line of scrimmage.

The best pass play to use in this situation is the triple stretch, which is also known as the vertical stretch. In this play, one receiver runs a deep pattern through the secondary, another receiver runs a route in the middle, and another simply runs underneath, as shown in Figure 8-10. The underneath route may be only 5 yards across the line of scrimmage and underneath the linebackers’ position in pass coverage.

The intermediate receiver runs a route behind the linebackers and in front of the secondary coverage players. Teams don’t necessarily want to throw deep, knowing that the defense is focused on preventing a huge gain, but that receiver must stretch the defense, or force the defense to retreat farther from the line of scrimmage. You use the deep receiver as a decoy.

The quarterback’s intention is to find the intermediate receiver (WR who comes in from the left). If the intermediate receiver can run behind the linebackers and catch the ball, he’ll probably have a 15-yard gain, but he’ll have to make sure that he runs out of bounds to stop the clock and conserve time. If the short receiver catches the ball, the linebackers are probably playing deep to prevent the intermediate receiver from catching the ball. In this situation, you dump it to the running back. He catches it and has a chance to run, but he must make sure he gets out of bounds, too. If the defense blitzes, you may be able to complete the deep route for a long touchdown pass. The quarterback normally reads progression from deep to intermediate and underneath, knowing that the defense is set up for the middle route.

Scoring Offenses

After you get the ball downfield and get out of all those sticky situations, your offense is ready to score. In the following sections, you can find plays for various scoring situations.

Making the best run play on the goal line

Actually I can’t tell you the best run play on the goal line because there’s no best play. But I can tell you that teams that have the most success running on the goal line have a great back like Hall of Famers Jim Brown or Marcus Allen in their backfield. Teams are always searching for a great running back, someone who can fight through three defenders, for example, and still reach the end zone.

The best running back in the NFL isn’t necessarily the one that coaches choose when their teams are near the goal line. The “dodger and dancer” type of runner who can break out in the open field isn’t as valuable near the goal line as the “pound it in there” guy. Down on the 1-yard line, you need a powerful runner — a tough, physical player — who can bowl over people. Because he’s going to be hit, he needs to be able to bounce off one or two tacklers. Well, okay. The best play at the goal line is always something straight ahead.

The best running back in the NFL isn’t necessarily the one that coaches choose when their teams are near the goal line. The “dodger and dancer” type of runner who can break out in the open field isn’t as valuable near the goal line as the “pound it in there” guy. Down on the 1-yard line, you need a powerful runner — a tough, physical player — who can bowl over people. Because he’s going to be hit, he needs to be able to bounce off one or two tacklers. Well, okay. The best play at the goal line is always something straight ahead.

Scoring inside the opponent’s 10-yard line

One pass in today’s NFL offenses is perfectly suited to the part of the field inside the 10-yard line: the quick out. As shown in Figure 8-11, the outside receiver (WR on the left) runs straight for 5 to 7 yards and then breaks quickly to the outside. Offenses use this pass play a lot because many defenses play the old college zone defense of putting their four defensive backs deep and back, which is called the four-across alignment (see the earlier “Defeating the four-across defense” section for more).

If you have a big, physical receiver, the quick out is the ideal pass. The receiver and the quarterback have to be in unison and time it right. If the quarterback completes the pass, the receiver has a chance to break a tackle and run in for a touchdown. The opportunity to score is there because in the four-across alignment, the defensive back doesn’t have help on that side; he must make the tackle by himself. If he doesn’t, the receiver can score an easy six points. Of course, the quick out is also a dangerous pass to throw. If the cornerback reads the play quickly and the quarterback fails to throw hard and accurately, the ball is likely to be intercepted by the defensive player and returned for a touchdown.

Going for two-point conversions

After scoring a touchdown, a team has two options: kick the ball through the uprights for one point or try for a two-point conversion. The team earns two points if it successfully reaches the end zone on either a pass or a run after a touchdown.

For a two-point conversion in the NFL, the ball is placed on the 2-yard line, the same spot as for a kick. (College and high school teams must score from the 3-yard line.) You’d think that the two points would be automatic, but over the years, two-point conversions have been successful just 47 percent of the time, whereas kickers convert extra-point attempts at a rate of around 99 percent.

Coaches have a universal chart that tells them when to kick and when to attempt a two-point conversion (the chart was supposedly devised by UCLA coach Tommy Prothro in 1970 with the help of his offensive coordinator, Dick Vermeil). Coaches like the chart because they dislike being second-guessed by players and the media for making the wrong choice — a decision that may result in a defeat. Here’s what the chart says:

-

If you’re behind by 2, 5, 9, 12, or 16 points, attempt a two-point conversion.

-

If you’re ahead by 1, 4, 5, 12, 15, or 19 points, attempt a two-point conversion.

-

If you’re behind by 1, 4, or 11 points, you have to make the dreaded judgment call — it can go either way.

Teams elect to go for two points when they need to close the point differential with their opponent. For example, if a team is behind by five, kicking the extra point would close the gap to four. That means the team could kick a field goal (worth three points) and still lose the game. But a two-point conversion would reduce the deficit to three, and a field goal would tie the game. When behind by nine points, a two-point conversion reduces the deficit to seven, meaning that a touchdown and an extra point could tie the game.

Teams elect to go for two points when they need to close the point differential with their opponent. For example, if a team is behind by five, kicking the extra point would close the gap to four. That means the team could kick a field goal (worth three points) and still lose the game. But a two-point conversion would reduce the deficit to three, and a field goal would tie the game. When behind by nine points, a two-point conversion reduces the deficit to seven, meaning that a touchdown and an extra point could tie the game.

The two-point conversion, with the right multiples of field goals and touchdowns, can close a deficit or widen it, depending on the situation. It’s a gamble. But when a team is trailing, it may be the quickest way to rally and possibly force overtime. Most coaches prefer to tie in regulation and take their chances with an overtime period. However, some coaches, especially if their teams have grabbed the momentum or seem unstoppable on offense, may elect to try two points at the end of the game and go for the win rather than the tie. The previous play is more common in high school and college football than in the NFL, where coaches tend to be conservative because of playoff implications — and because a loss might mean unemployment.

Most teams use zone pass plays in two-point conversion situations because defenses aren’t playing man-to-man coverages as much anymore. So the following play was designed to succeed against a zone defense. Remember that the offense simply has to gain 2 yards (or 3 in high school and college) to reach the end zone, which doesn’t sound complicated.

To attempt a two-point conversion, the offense lines up three receivers to one side. One receiver runs the flat; another receiver runs up about 6 or 7 yards and runs a curl; and the third receiver runs to the back of the end zone, turns, and waits. Figure 8-12 shows three receivers (TE and WR) to one side — the right side. This group of receivers can be a tight end and two wide receivers — it doesn’t matter as long as the receivers are bunched together in a close group. One receiver runs straight ahead and about 2 yards deep into the end zone. Another receiver is the inside guy. He runs straight up the field. He heads first to the back of the end zone and turns to run a deep square-out. The other receiver just releases into the flat area, outside the numbers on the field. If the quarterback looks into the secondary and believes that he’s facing a zone defense, he wants the receiver running the 6'yard curl to come open.

If the defense is playing a man-to-man coverage, the quarterback wants the receiver in the flat to come open immediately. If the defense reads the play perfectly, the quarterback is in trouble because he must find a secondary target while under a heavy pass-rush. Still, this pass is almost impossible to defend because the offense is prepared for every defensive concept.

If the coverage is man-to-man, the offense opens with a double pick, which is illegal if the officials see it clearly. By a pick, I mean that an offensive receiver intentionally blocks the path of a defensive player who’s trying to stay with the receiver he’s responsible for covering. Both the tight end and one receiver on the right side attempt to pick the defensive player covering the receiver (refer to Figure 8-12) running toward the flat area. If the receiver who’s benefiting from the illegal pick doesn’t come open, the first receiver attempting a pick runs 2 yards into the end zone and curls, facing the quarterback. After trying to pick a defender and if he believes he’s wide open, the tight end settles, stops to the right of the formation, and waves his arm so the quarterback can see him.

Disguising a Successful Play

During the course of a game, a team often finds that one pass play works particularly well against a certain defense and matchup. To keep using the play in that game and to continue to confuse the defense, the offense often runs the pass play out of different formations while maintaining similar pass routes.

As an example, here’s what an offense originally does: It lines up with three receivers (WR), a tight end (TE), and a running back (RB), as shown in Figure 8-13. One receiver is to the left, and the running back is also behind the line to the left, behind the left tackle. The tight end is aligned to the right, and two other receivers are outside of him. The receiver on the left runs down the field 18 yards and runs a square-in (for more on this passing route, see Chapter 5). The tight end runs a crossing route, about 7 or 8 yards from the line of scrimmage. The running back swings out of the backfield to the left.

The receiver located in the slot to the right simply runs right down the middle of the field. He’s the deep decoy receiver who’s going to pull all the defensive players out of the middle. The quarterback wants to hit the receiver who lined up on the left side. If he isn’t open, he tries the middle with the tight end; lastly, he dumps the ball to the running back.

To modify this successful play, the same receiver on the left runs the same 18-yard square-in, as shown in Figure 8-14. The running back on the left releases to that side, but this time he runs across the line of scrimmage 7 or 8 yards and curls back toward the quarterback. The back is now assuming the role of the tight end in the original formation. This time, the tight end runs down the middle of the field. The receiver in the slot now runs right between the two hashes and hooks. So it’s pretty much the same play. The offense’s target remains the receiver to the left. And all those other receivers are simply decoys.

Running specialized pass offenses and exploring new offensive formations

Running specialized pass offenses and exploring new offensive formations Defeating different defensive fronts

Defeating different defensive fronts Discovering how to gain yards

Discovering how to gain yards Deciding when to gamble on offense

Deciding when to gamble on offense Choosing a goal-line offense

Choosing a goal-line offense Here’s another thing you should know about offensive strategy: No perfect play exists for every occasion. In strategy sessions prior to a game, a play may look like it will result in a long gain, but in reality it may not succeed for various reasons. It may fail because someone on the offensive team doesn’t execute or because a defensive player simply anticipates correctly and makes a great play. Things happen!

Here’s another thing you should know about offensive strategy: No perfect play exists for every occasion. In strategy sessions prior to a game, a play may look like it will result in a long gain, but in reality it may not succeed for various reasons. It may fail because someone on the offensive team doesn’t execute or because a defensive player simply anticipates correctly and makes a great play. Things happen!

The best shotgun quarterback I ever saw was John Elway of the Denver Broncos. Jim Kelly of the Buffalo Bills truly excelled in the shotgun, too. Elway and Kelly seemed more comfortable and confident in this formation than other quarterbacks.

The best shotgun quarterback I ever saw was John Elway of the Denver Broncos. Jim Kelly of the Buffalo Bills truly excelled in the shotgun, too. Elway and Kelly seemed more comfortable and confident in this formation than other quarterbacks.

The quarterback throws to his left because the ball is placed on the left hash mark, which is the short side of the field. Throwing a 15-yard comeback pass to his left is much easier than throwing a 15-yard comeback to the right, or the wide side of the field. The pass to the wide side would have to travel much farther, almost 42 yards, as opposed to just 15 yards. From the left hash mark to the numbers on the right side of the field, the distance is more than 19 yards. And the comeback to the right is always thrown beyond those numbers (10, 20, 30, 40), going down the length of the field.

The quarterback throws to his left because the ball is placed on the left hash mark, which is the short side of the field. Throwing a 15-yard comeback pass to his left is much easier than throwing a 15-yard comeback to the right, or the wide side of the field. The pass to the wide side would have to travel much farther, almost 42 yards, as opposed to just 15 yards. From the left hash mark to the numbers on the right side of the field, the distance is more than 19 yards. And the comeback to the right is always thrown beyond those numbers (10, 20, 30, 40), going down the length of the field.

A coach’s strategy may change drastically when his team is playing the same opponent in its own stadium. If I’m playing in my stadium and I’m leading 17–7 in the fourth quarter, I may go for it on fourth-and-1 — especially if we’re inside the other team’s 20-yard line. I may let my team take a shot, especially if the offense hasn’t been very effective. If my team doesn’t make the first down, the other team has to go more than 80 yards to score, and it has to score twice to beat me. You’d rather be in the other team’s territory when you gamble. Never gamble in your own territory — it could cost your team three points or a touchdown.

A coach’s strategy may change drastically when his team is playing the same opponent in its own stadium. If I’m playing in my stadium and I’m leading 17–7 in the fourth quarter, I may go for it on fourth-and-1 — especially if we’re inside the other team’s 20-yard line. I may let my team take a shot, especially if the offense hasn’t been very effective. If my team doesn’t make the first down, the other team has to go more than 80 yards to score, and it has to score twice to beat me. You’d rather be in the other team’s territory when you gamble. Never gamble in your own territory — it could cost your team three points or a touchdown.