| ∎ | 7 | ∎ |

UTOPIAN REALISM IN ONLINE COMMUNITIES

Drawing on Ernst Bloch’s work in The Principle of Hope, Fredric Jameson distinguishes between utopia as program and utopia as impulse. Utopian programs include all systematic efforts to found a new society, such as a revolution and a commune. While utopian programs are limited in number, utopia as impulse is pervasive, “finding its way to the surface in a variety of covert expressions and practices.”1 Jameson mentions such examples as political and social theory and social democratic and liberal reforms. For Jameson, the value of utopia lies in its “critical negativity as a conceptual instrument designed, not to produce some full representation, but rather to discredit and demystify the claims to full representation of its opposite number.”2 He sees its function “not in itself, but in its capability radically to negate its alternative.”3

Jameson’s work represents only the most recent intellectual project to affirm the value of utopia in a dystopian world. Anthony Giddens’s notion of “utopian realism” is another.4 For Giddens, utopian realism is hope rooted in reality rather than in fancy. By affirming the theoretical possibilities of immanent institutional self-transformation and embracing the project of human emancipation and self-actualization, Giddens sounds a note of hope in the face of what appears to be a doomed modernity. For both Jameson and Giddens, reaffirming the value of utopia provides a critical approach to the postutopian world of global capitalism.

The visions articulated by Jameson and Giddens are intellectual visions. Jameson’s is a study of science fiction. Giddens’s vision issues from his critical theory of contemporary Western modernity, but it is expressed more as a conviction than as an analysis of practical struggle. Neither of them uncovers the utopian impulse in social practice.

The practical struggle in contemporary China contains a utopian impulse. It is discernible in many areas of the new citizen activism, such as the environmentalists’ yearning for alternative world views and an alternative society. But nowhere else is it more vibrant than in Chinese online communities. A new digital formation that emerges through the use of the Internet,5 online communities are perhaps the most important new associational form to have emerged since the 1990s. Numbering in the millions, they exist in newsgroups, mailing lists, chat rooms, BBS forums, and blogs. Their sheer size means that they encompass the spectrum of human motivations and behavior, high and low. My goal in this chapter is to analyze a particularly vibrant yet neglected aspect in this spectrum: the utopian impulse.

What is most striking about Chinese online communities is not their practical and utilitarian functions, which are numerous, but how they nurture moral sentiments. Like any utopia, this utopian impulse is a critique of the present and a yearning for a better world. It originates in the social, cultural, and political displacements associated with the market transformation. Under the conditions of displacement, online communities become a space for reorientation. They are where people exert their “work of the imagination,” as Arjun Appadurai might put it.6 The alternative world envisioned is often colored by some degree of idealization. Yet such idealization, or utopian thinking, is by no means rootless. It originates in discontents with social reality. Nor is the utopian impulse only expressed in thinking. It is just as often found in social practice. The construction of online communities is one such social practice, for this process is about defining and affirming common values, the most sacred values being those often considered damaged in contemporary society—freedom, trust, and justice. The practical expressions of the utopian impulse are also seen in offline action. My case study later in this chapter will demonstrate how the utopian impulse moves between thinking and action and between online and offline communities. It is because the utopian impulse is rooted in reality, in hope, and in action that I will consider it as a form of utopian realism, to borrow Giddens’s language.

Space, Community, and Chinese Modernity

In general social science, online communities have attracted much attention. Earlier studies debated about whether online communities are “real” or virtual and whether the Internet “will create wonderful new forms of community or will destroy community altogether.”7 Barry Wellman and Milena Gulia, the authors of the above statement, begin their article with the following questions: “Can people use the Internet to find community? Can online relationships between people who never see, smell, or hear each other be supportive and intimate?”8 The earnestness to prove the realness of online communities led to a research focus on the practical functions of online communities and, by extension, an emphasis on their practical and utilitarian aspects. Little attention is given to nonutilitarian issues of pleasure, play, identity, and morality.

Despite the boom of online communities in Chinese cyberspace, there are few scholarly studies. Among existing works, Michel Hockx has examined online literary communities through a case study of the literary Web site Rongshu xia [Under the banyan tree]. He finds a high degree of continuity between today’s online literary communities and literary journals of the early twentieth century. For example, online literary communities use some similar methods of community building, such as organizing literary clubs, conducting workshops for readers, and holding literary competitions.9 Furthermore, both the literary journals of earlier times and online literary communities today involved readers in debates on social issues and helped to bring critical issues into the public sphere. Hockx’s study thus highlights the historical links of online communities with respect to both the goals and methods of community construction.

Online communities have attracted some attention among scholars inside China. The most systematic empirical study so far is anthropologist Liu Huaqin’s ethnography of Tianya communities.10 Liu shows that Tianya communities take on features of social stratification and social conflicts common in offline social organizations. Her analysis focuses purely on the internal features of online communities without linking them to the broader social context. She rejects the hypothesis that the rise of online communities responds to the decline of offline communities and represents a search for meaning in a disorienting society. Instead, she resorts to Maslow’s psychology of the hierarchy of needs to argue that online communities exist because they meet different needs, including ones people cannot satisfy in reality. Her detailed analysis of the internal structures of Tianya.cn implies that online communities are replications of offline social forms and downplays their unique features and the ways in which online communities transcend offline communities. It is inevitable that familiar social practices will be brought into cyberspace, but I will argue that online communities differ from existing social structures in some fundamental ways.

The paucity of scholarship on Chinese online communities is partly due to the concentration of research energies on the political dimensions of the Internet, such as political control. There has also emerged an uncritical new conventional wisdom, perpetuated by mass-media stories and corroborated by survey reports, that Chinese Internet users go online mostly for entertainment and not for politics. Not only is politics understood in a misleadingly narrow sense, but the view of entertainment as mere play devoid of politics is simplistic.11

Outside the field of Internet studies, a sophisticated literature on the spatial transformation of China has raised important questions with direct bearings on the analysis of online communities. Essays in Urban Spaces in Contemporary China (1995) capture the growing sense of personal autonomy and the rise of new community forms in the 1980s and early 1990s.12 The volume indicates how changes in the physical environment are linked to the transformation of urban public and private life and how social practices in physical locations transform them into social spaces. Nancy Chen’s “Urban Spaces and Experiences of Qigong” is an interesting case in point. She explores popular qigong practices that came into fashion in the mid-1980s. These practices take place in a variety of public venues—urban parks, workunit compounds, and streets and sidewalks. The activities in these public arenas, such as “breathing exercises” and tango,13 turned them into social spaces for organizational life. It was in these spaces, Chen argues, that various kinds of official and unofficial qigong associations mushroomed.14 Falun Gong was originally one of those qigong associations.

The deepening of the market transformations since the 1990s creates a crisis of spatial dislocation. In urban and rural China alike, spaces become sites of political struggle and resistance. Anthropologists Xin Liu, Mayfair Yang, and Li Zhang, among others, have all posited the centrality of space as an analytical category for understanding contemporary urban China. In interrogating the urban question, Liu argues that “the current problematic of understanding the transition in China is to understand its spatial character,” because “space has become a dominant form of everyday consciousness” and the production of social relations increasingly takes place through spatial production.15 Li Zhang offers an account of China’s pursuit of modernity by analyzing “how temporal notions such as ‘progress’ and ‘backwardness,’ ‘modern’ and ‘lagging behind’ have produced a particular kind of city restructuring.”16

Mayfair Yang’s study of a rural Wenzhou community shows that rural ritual spaces of popular divinities are battlegrounds “for the reappropriation of space by local communities”:

In these spatial havens, people construct new alternative identities and come together through pathways not forged by state administration. Here, they conduct rituals in which bodies mediate between earthly and divine realms, helping dispel the monopoly of state-capital abstract space. They also experiment with new forms of organization and decision making, the production of community spaces, and collective acts of resistance.17

As a new spatial form, online communities are “spatial havens” and sites of resistance as much as these rural communities are. They are another frontier where citizens construct alternative identities, imagine new worlds, experiment with new organizational forms, and engage in new forms of resistance.

The Development of Chinese Online Communities

Chinese online communities are the products of historical circumstances. From the very beginning, they met people’s social, cultural, and political needs. The earliest Chinese online communities appeared among the Chinese diaspora in the 1980s. The newsgroups and online magazines among overseas Chinese students were primitive forms of online communities. A distinct feature of these communities was that they were built by people away from their families and native country. They had only the traditional media—airmail and telephones—to maintain contact, and these were slow and expensive.18 For Chinese students at that time, the main source of news about China was the Chinese newspapers in main university libraries, which usually arrived several weeks late. Unsurprisingly, the online newsletters and magazines they edited and circulated online became important sources of information.19

The earliest Chinese online magazines were set up in the early 1990s by Chinese students in North America. They were often based in a university. Some of these disappeared after a while, others have persisted, and still others have evolved into influential nonprofit organizations or commercial portal sites. Among the best-known online magazines are Olive Tree (wenxue. com) and China News Digest (cnd.org). Both are now nonprofit organizations based in the United States. Olive Tree is a literary monthly founded in 1995. Its mission is “to establish a mass-media outlet for new literary works and culture commentaries in Chinese, a platform with a lot less political, social, and economic restrictions normally associated with mass market.”20 Its editors are volunteers in China, North America, and other parts of the world. They claim no identification with any nation-state.

China News Digest was launched on March 6, 1989, by four Chinese students in Canada and the United States. Originally published only in English and intended as a communication network for Chinese students in North America, CND has developed into a global network of English-language news services, a weekly Chinese-language online magazine, discussion forums, and online archives of significant historical events in Chinese history, including archives on China’s Cultural Revolution and the democracy movement in 1989. Its readership has been growing steadily. When it was first set up in 1989, CND had only four hundred subscribers, all in Canada and the United States. By 1999, it had about fifty thousand subscribers in 111 different countries or regions of the world. Table 7.1 shows the growth of CND readership from 1989 to 1999.

In production, distribution, and contents, overseas online Chinese magazines manifest important new features associated with the new medium. One feature is voluntary self-publishing. The production and distribution of print magazines are centralized in China, with stringent licensing procedures and editorial control. In contrast, the publishing of online Chinese magazines was self-organized and voluntary from the very beginning. Some were affiliated with Chinese student associations; others were launched and run by individuals. Even those affiliated with student associations, such as Feng Hua Yuan in Canada, rely on volunteers in the editing and production process.

Another crucial feature in the production of these online magazines is that it involves transnational collaboration. The editorial staff of most online magazines consists of volunteers scattered throughout the world. Residing in different time zones and with no central editorial office to speak of, volunteer editors work primarily via e-mail. On the occasion of the publication of its hundredth issue, an editor of CND’s Hua xia wen zhai wrote:

Hua xia wen zhai is a Chinese magazine. Yet because we are scattered in all corners of the world, much of the discussion among editors takes place in English via e-mail. With the appearance of Chinese software aimed to promote Internet communication in Chinese (especially ZWDOS written by Ya Gui), more and more editors have, as Wen Bing puts it, “taken to Chinese e-sisters.”21

Sometimes we “talk” about CND business over the Internet. Once I chatted with Xiong Bo for a whole night until day broke on his side. Sometimes we “talk” with readers and authors. We are quite used to modern computer networking technology. But one experience has left a particularly strong impression on me. That was early July last year. I was “talking” with Ming Hui thousands of miles away and it was the first time I used ZWDOS22 to write Chinese characters. It was very slow. Each of us wrote only a few characters, but that was enough to drive me mad with joy. I stomped my feet and shouted wildly.23

TABLE 7.1 CND Readership, 1989–1999

Source: CND, March 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1997, 1999.

*This number is based on my estimate. According to CND, it had 47,600 subscribers among an estimated total readership of 150,000 in 1997. CND estimated that its readership had reached 180,000 by March 1999, but it did not publish the number of subscribers. Since 47,600 accounts for 31.7% of a readership of 150,000, it can be inferred that given a readership of 180,000, 31.7%, or 57,120, are subscribers.

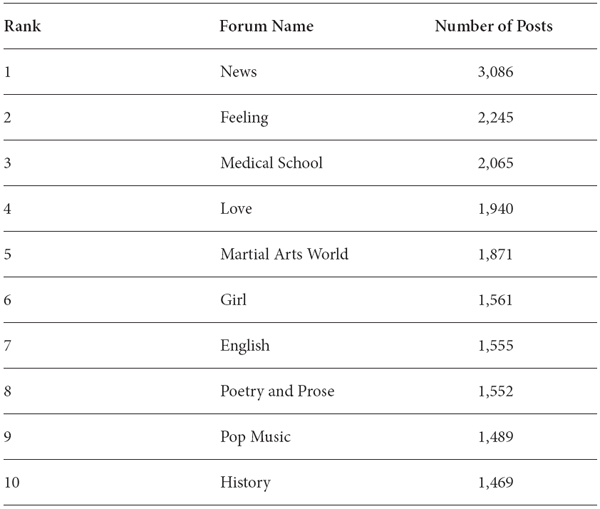

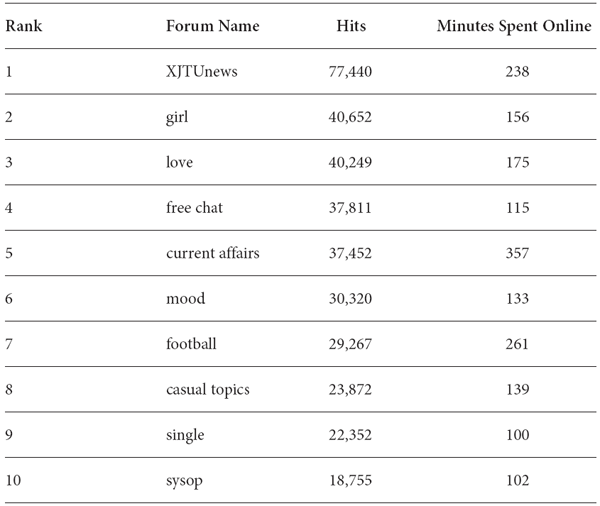

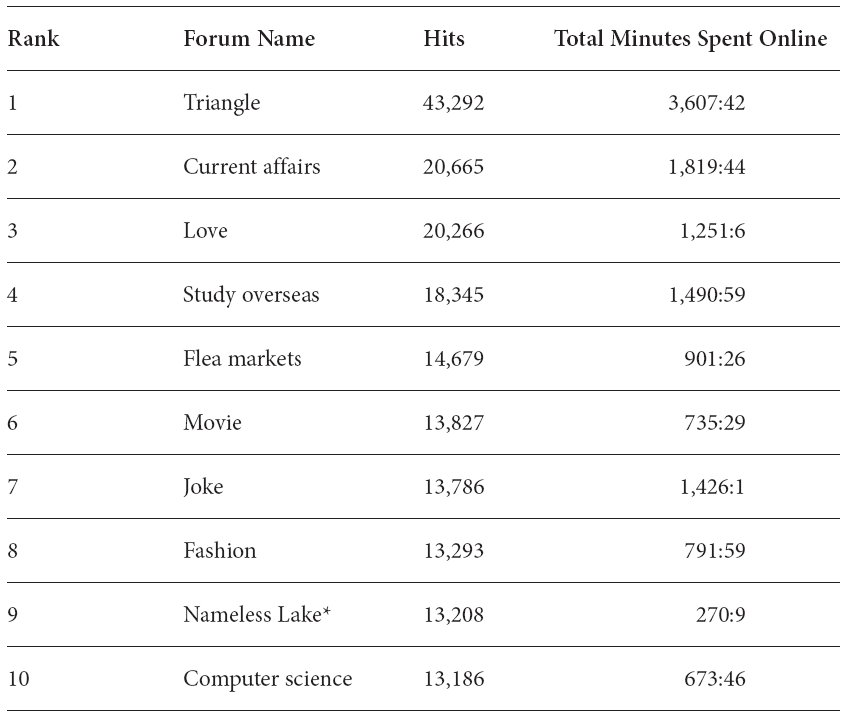

Inside China, the earliest online communities were BBS forums among college students. BBSs were first opened in universities and then in commercial portal sites. Thus the first contingent of BBS-based online communities appeared among college students. Tsinghua University led the way, where China’s first BBS, called SMTH (short for Shuimu Tsinghua), opened in 1995. Others quickly followed at Beijing University, Nanjing University, Zhejiang University, Fudan University, Xi’an Jiaotong University, and so forth. In November 2000, Sohu.com listed seventy university-based BBSs.24 In almost all cases, one BBS system supports numerous forums classified by topics of interest. For example, on December 8, 2000, Beijing University had 149 forums in its BBS and Xian Jiaotong University had 129 forums.25 Forums about current affairs and personal relationships were usually popular, but the broad range of topics indicated that people joined the forums for diverse reasons. Tables 7.2 and 7.3 list the ten most popular BBS forums in Shantou University and Xi’an Jiaotong University respectively, as of May 21, 2000. Table 7.4 shows the top ten BBS forums in Beijing University on April 23, 2002.

TABLE 7.2 Top Ten Forums in Tulip BBS, Shantou University, May 21, 2000

Source: bbs.stu.edu.cn/bbs-cgi/bbsall, accessed May 21, 2000.

As BBSs appeared in universities, official media institutions began to go online and commercial Web sites offered free Web space for personal homepages. BBS-based communities proliferated. The first government-sponsored magazine to go online was Shenzhou xueren [China scholars abroad], a magazine targeting overseas Chinese students. This happened in 1995, the same year as the launching of the SMTH BBS at Tsinghua University. Also in 1995, Zhongguo maoyi bao [China trade news] and China Daily went online. By the end of 1996, more than thirty newspapers had launched online editions.26

The first commercial Internet service provider (ISP) was started in 1995 by Jasmine Zhang.27 Zhang’s company was probably the first private business to offer BBS services. It also opened the first Internet cafe in China. The next two years, 1996 and 1997, saw the first major wave of commercialization of the Internet in China. As a result, as Ernest Wilson III puts it, “by 1996 the average Chinese could, with adequate financial and cognitive resources, gain access to a national network for e-mail and other services on the global Internet.”28

TABLE 7.3 Top Ten BBS Forums at Xi’an Jiaotong University, by Number of Hits, May 20, 2000

Source: bbs.xjtu.edu.cn/cgi-bin/bbsanc?path=/bbslist/board2, accessed May 20, 2000.

These other services included BBSs and free Web space for personal homepages. Sitong Lifang, or Sisnet, which would later merge with the Silicon Valley–based Sinanet (Huayuan) to form Sina.com in 1998, was already offering BBS services in 1996. Initially, Sitong set up BBS forums to provide customer support. Its CEO, Wang Zhidong, personally used the BBS forum to answer customers’ questions. But soon they found that the users of their BBS forum were from all over the world and the discussions quickly moved from technical problems to all kinds of topics. As Wang recalls,

Later, people no longer talked about technical issues but started to chat about all kinds of things. After we found out this problem, our first reaction was to try to kick them out of the forum and remove things not related to technical discussions. But the customers did not listen. So we thought about splitting the forum into two. We set up a forum called “Talk Heaven and Speak Earth,” separate from the technical forum. People could go there to talk about anything they wanted.29

TABLE 7.4 Top Ten BBS Forums in Beijing University by Number of Hits, April 23, 2002

Source: bbs.pku.edu.cn, accessed May 20, 2000.

* Nameless Lake is a lake at the center of the campus and the symbol of Beijing University.

An influential event in the expansion of personal Web pages was the launching of Netease.com in May 1997. Netease.com offered sizeable free Web space for hosting personal homepages, and many Chinese took advantage of the service. According to one estimate, as of 1999, more than 80 percent of China’s personal homepages were hosted by Netease.com.30 Although these were personal homepages, many became small online communities through multiple links to other Web sites, e-mail communication among site owners, and interaction through guest books or BBS forums. They were the predecessors of the blogs.

TABLE 7.5 Chinese-Language BBS Forums by Thematic Category, Geocities.com, April 13, 2002

| Thematic Category | Number of BBSs |

| General | 45 |

| Politics | 77 |

| Military affairs | 21 |

| Culture, sports, and art | 113 |

| Campus, overseas students, and overseas life | 70 |

| Science and economy | 70 |

| Emotional communication | 47 |

| Total | 443 |

Source: http://www.geocities.com/Paris/Lights/4323/top20.html.

When blogs appeared, some people predicted that they would soon replace the BBS forums. This has not happened. On the contrary, BBS-based online communities have become more and more popular and dynamic. In 1999, 28 percent of all Internet users (over one million) were frequent BBS users. Despite fluctuations, BBS use has remained at high levels (see tables 5.2 and 5.3). According to one estimate, there were 100,000 BBS communities in China as of 2003.31 By 2005, over 40 percent of China’s 103 million Internet users were using BBS forums. Table 7.5 shows Geocities.com’s listing of the number of BBS forums classified by theme as of April 13, 2002. Table 7.6 shows the top ten Chinese-language BBS forums measured by the number of posts on November 27, 2000.

TABLE 7.6 Top Ten Chinese-Language BBS Forums Listed by Geocities.com, November 27, 2000

| Forum Name | Number of Posts |

| Strengthening the Nation | 1,258,720 |

| Sina Sports Salon | 808,912 |

| Shida BBS on military affairs | 277,931 |

| World Military Forum | 234,327 |

| Renaissance | 75,863 |

| North America Freedom Forum | 67,340 |

| China forum for sexual love | 54,014 |

| Everyone’s Forum | 44,622 |

| Asia Military Affairs | 44,050 |

| Muzi Forum | 20,000 |

Source: www.geocities.com/Paris/Lights/4323/top20.html, accessed November 27, 2000.

With a new awareness of the importance of user-generated content among business entrepreneurs, online communities have grown bigger today. A typical online community integrates BBS forums, blogs, podcasting, videocasting, and other such functions into one massive system. The largest online communities, such as Tianya.cn, have millions of registered users. On July 20, 2007, China Internet Weekly published a cover story about online communities. One of the articles claims that “if you do not understand online communities, your life and business in the next twenty years will suffer enormous costs.”32 Another describes a community project in Nanjing City which integrates an online community with an offline neighborhood. The project was built on the basis of its brand-name online community, xici.net. The real-estate developer that built the new neighborhood contracted with the owner of the online community to use some of the names in the online community in the offline neighborhood. For example, xici.net has a popular forum on film reviews called “Watching Films from the Back Window” (houchuang kan dianying). A main film center in the neighborhood was then named after the forum. With this new offline community, members of the online community can easily move between their online and offline worlds in their social interactions.33 The same special issue lists the twenty most influential online communities as of July 2007 (reproduced here as table 7.7).

TABLE 7.7 Top Twenty Online Communities in China Listed by China Internet Weekly, July 20, 2007

| Web site | Year established |

| Mop.com | 1997 |

| Xici.net | 1998 |

| Tianya.cn | 1999 |

| Xilu.com | 1999 |

| bbs.people.com.cn | 1999 |

| 55188.com | 1999 |

| xitek.com | 2000 |

| doyouhike.net | 2000 |

| hl365.net | 2001 |

| tiexue.net | 2001 |

| xcar.com.cn | 2002 |

| Verycd.com | 2003 |

| 55bbs.com | 2004 |

| Wealink.com | 2004 |

| Ipart.cn | 2005 |

| Douban.com | 2005 |

| 51credit.com | 2005 |

| tudou.com | 2005 |

| maxpda.com | 2006 |

| babytree.com | 2007 |

These online communities cater to special groups of Internet users. For example, Tianya.cn and xilu.com are known for their intellectual orientations. Mop.com and Ipart.cn are popular with young people. 55bbs.com is a favorite with white-collar female consumers, while Babytree.com is a new Web site targeting young parents. The likelihood of the communities becoming spaces for activism varies with the areas of interest. Because it has many forums covering current affairs and social and cultural issues, Tianya.cn has been a hotbed for contention. This is also true of other general-interest online communities such as those hosted by sina.com, sohu.com, and netease.com. It is perfectly likely that members of specialized online communities may mobilize as well when issues of special concern to them arise. Were the members of babytree.com, who are most likely to be young parents, to find that the powered milk they feed their babies is a counterfeit brand, then the chances of mobilization would be high.

Images of Freedom in Online Communities

One way of capturing people’s idealizations of online community is to look at the images they use to describe them. Although people imagine their communities in all sorts of ways, in my research I found three groups of images to be especially prominent. One consists of such images as the public square (guangchang), tea house, coffee shop, and marketplace (jishi). These are images of openness and freedom. The second consists of images of family and home. These images emphasize sociality, solidarity, fellowship, belonging, and camaraderie. The third group of images is borrowed from the language of martial-arts fiction and films. The central image here is “Rivers and Lakes” (jianghu), which epitomizes the martial artist’s vision of the world as a world of freedom, adventure, and justice, but also of intrigue and betrayal.

These three sets of images, freedom, solidarity, and justice, are not separate. The yearning for freedom is sometimes expressed as a yearning for solidarity and justice, and vice versa. To varying degrees and in different mixtures, they are present in all kinds of online communities. Yet a pattern of change is discernible on closer examination. The images of freedom were most common in the earlier years of Internet diffusion in China, from about 1997 to 2000. They conveyed most vividly people’s initial enthusiasm for the newfound freedom of expression in online forums. Today, as Chinese cyberspace expands and becomes more of a space of adventure, social expression, and political struggle, martial-arts images have become more common. The yearning for freedom of expression is dampened by growing political control, but it is never lost. Instead, it manifests itself more as self-conscious struggles in a cyberworld increasingly seen as torn between the good and the evil, a world of Rivers and Lakes. The images of home and family have remained strong throughout and are often mixed with the other two images.

These images crystallize people’s visions of online communities, the values they treasure, and the ideals they aspire to. Below, I highlight the importance of these images through the voices of community members. Then I turn to a case study of a contentious event to show how a yearning for these values guides civic action and how the desire to maintain the purity of the community can lead to online radicalism such as Web hacking.

Images of freedom were prevalent in the early years of the Internet and may be found in numerous postings and personal stories about experiences with the Internet. Sina.com used to maintain an online archive of roughly eighty personal stories describing people’s encounters with Internet bars in various parts of the country, including some very remote and small towns. Many of these stories conveyed the sense of freedom people found on the Internet. For example, in February 1999, when Internet bars were beginning to sprout across China, one patron in the city of Nanjing wrote the following:

If you think about it, the virtual space constructed on the Internet is much more expansive and boundless than the oceans imagined by generations of poets. On the Internet, people travel freely in the boundless spaces of their imagination, so much less constrained by the limited spaces in real life. To use boundless imagination to change the bounded reality and improve the quality of human existence—this is perhaps a basic principle in the progress and development of human civilization.34

Notwithstanding the romanticized notion about the progress of human civilizations, the author of this passage conveyed clearly the importance of the Internet for “the work of the imagination.” The Internet autobiographies I collected similarly convey this sense of freedom. One author, a twenty-one-year-old male college student, wrote: “Going online is like my second life. You do what you want to do, say what you want to say. It’s easy to make friends. If you meet people you cannot get along with, you can easily stop meeting them. How nice.”

While people express excitement about social freedom online, it is the newfound sense of political freedom they are most excited about. In chapter 4, I discussed popular enthusiasm about the Internet as reflected in a sample of 289 posts archived in the Strengthening the Nation forum (SNF). That people devoted time and energy to writing lengthy messages about the forum was in itself a sign of enthusiasm. By my count, the 289 posts contain at least 150 specific suggestions about how to improve SNF. One type of suggestion concerns matters of operating and managing the forum. They include some technical advice, but the central concern is about how to develop an open and clearly formulated system of management. “As in real life, a forum also needs order,” the author of post 14 explained: “I think the key issue in the management of the forum is to establish a clear and precise set of rules. These rules should be publicized. Whether the rules are just or reasonable enough is not a big problem (after all this is a forum of a party newspaper; it cannot be free from its own biases). The important thing is to follow rules. Then net friends will not have so many complaints.”35

In post 168, the author discussed two contradictions in SNF: it is a free online space, yet this freedom is a contributing factor to meaningless quarrels and personal attacks. As an online forum, SNF should have freedom of speech, yet because of its official background, it necessarily exerts some control. The author then explained that because of these contradictions, some compromise between SNF users and hosts is necessary for the proper operations of the forum. SNF should develop and strictly follow a system of rules. These rules are essential for rational online discussions. At the same time, because of SNF’s popularity and special status, it should create an open and free atmosphere in order to demonstrate to the Chinese government how the new medium may operate in a free atmosphere and to show Internet users how to use their rights of freedom of speech.

Another type of suggestion concerns the format and content of the discussions. One suggestion is that SNF should not artificially limit discussion topics or issues. Postings critical of the government should be welcome, because, as the author of post 149 argued, the purpose of having an online forum is not to have another place to sing eulogies for the government—the official newspapers serve that purpose only too well!

Finally, some posts discuss SNF’s potential functions. Users are aware that SNF is beginning to play an important role as “a clearinghouse for world news, different viewpoints, and people’s voices” (post 199). Their suggestions collectively amount to a vision of what an ideal forum should look like. Some proposed that SNF could serve China’s democratic governance. Post 8 submits that SNF could become an online RAND company for the Chinese government. Post 82 suggests that “SNF should be a place for hearing people’s voices and providing input for government decision making.” Others emphasized democratic participation: SNF should become a channel for ordinary citizens to participate in government. “The forum should become a people’s democratic square” (post 50). The multiple voices in the forum should be published in the pages of official news media (posts 23 and 99). A persistent theme was for SNF to make use of its special space to promote democratic politics in China.

Images of Home in Online Communities

The second group of images of online communities centers on family and home. In the late 1990s, when people first began to go online and set up personal Web sites, it was customary to compare their Web sites to a home. Site owners often published personal statements about why and how they built their sites. Some published diaries to chronicle the changes they made to their Web sites. The owner of one such personal homepage wrote: “It is almost two years since I went online. I always wanted to create a beautiful personal home page, but because I didn’t know [homepage making] very well, my first homepage did not go up until May 1999. In any case, I finally had a ‘home’ online.”36 A diary entry dated August 25, 2000, reads: “Today I decided to make a homepage. I have wanted to do this for a long time. I want to set up a home online and put some of my favorite stuff here. I have never created a homepage before, but have used FP2000.37 I thought it doesn’t matter whether it is good or bad. Just create one first.”38 A diary entry dated September 2, 2000, reports, “Today, I finally uploaded my home page. I felt as happy as a sparrow. Although I found a few bugs, still I finally got a home. Hehe.”39

The image of home comes across most strikingly in the Internet autobiographies I collected. For example, a young man wrote the following about his online experiences:

I remember there was a BBS called “Search 3.” It attracted many trendy young people. I was lured there too. There was a literary forum there for literature lovers to communicate and discuss things. There were also many works of literature you could read…. Gradually, I was attracted by this BBS. There, you could talk about anything without constraint. It was different from school, where you had to follow the ideas in the textbooks whenever you spoke and you would be scolded by teachers if you were not cautious. Here if there was anything you disagreed with or didn’t like, you could talk back. I often quarreled with people endlessly. Sometimes we debated all night without any sleep. That kind of fun I never experienced in the offline world. After a period of communication, I became very close to those net friends. We became such good friends that we would talk about anything. But that was after all on the Internet, a virtual world. We decided to organize a gathering of net friends and make the virtual real. We shared the expenses of the party. At the party, we were like long-separated old friends. It was hard to describe how excited we felt in our hearts (Male, 21, BioH1).

The young man quoted above is most fascinated by the sense of freedom and sociality he found in cyberspace. Debate is a pleasure; even quarreling becomes fun. He contrasts what he can do with his online friends with what he cannot do at school, where he feels he has to follow the mode of thinking prescribed in school textbooks. Below is a young girl’s tale:

Today two years ago, I met “Flower’s baby” in “Sister rabbit’s” personal message board [tieba]40—the queen of watering41 in the “Youba” message board. We got along very well. Therefore, me, Rabbit, and Flower began our career of watering the “Youba.”… At the end of 2005, Flower applied for and set up a message board called “Watching Water.” Thereafter, our “Watching Water” team was formally established…. “Watching Water” gradually turned into a big family. We lived in harmony and heart-warming joy. However, just when I was happily watering these message boards, my senior year in high school befell me. My family felt the computer was too much of an interference for me. Thus in January 2006 my computer was taken away. It is not that I did not protest, but there was no use…. I said goodbye to my net friends in tears. Four months passed…. During this period, whenever I had nothing to do and felt lonely, I couldn’t help thinking of my home on the Internet, as if that place had become my spiritual pillar. That was a place I could always return to, where there were friends waiting. Whenever I thought of these things, my heart was filled with warmth (Female, 19, college student, Bio10).

Here we see the same sense of excitement and thrill about online communities, but again, it is not about the practical functions but rather about the sense of freedom and fellowship. This sense of joy became more acute when the young girl had to abandon her online friends under pressure. In times of loneliness, as she put it, she recalled with great warmth her “home in cyberspace.” The autobiography she wrote has a distinctive tone and is conveyed in an unconventional language and style. Many terms and ID names may sound bizarre and incomprehensible, but she spoke of them as if they were a natural part of her life.

The authors of these two stories are college students. But what about their parents’ generation? The following story, by a former sent-down youth (of the Cultural Revolution generation), conveys the same kind of joy:

I have used the computer for five or six years, mainly for typing, which is very convenient. Occasionally, I would surf online, but felt there wasn’t much fun. One reason was that the speed was slow…. Then my home computer was connected to the broadband network and the speed became fast. Whenever I get a chance I would surf online, mainly to search for Web sites about former zhiqing. For many years, I kept a strong “zhiqing complex.” I wanted to establish some kind of connection with former zhiqing who had similar life experiences. I wanted to find a home that belonged to former zhiqing. Yet for about half a year, I didn’t even find one. At that time, I really felt sad for us zhiqing. I thought former zhiqing had either retired or been laid off and, as a social group, had already been forgotten by the society. I thought I was a lonely ghost wandering on the Web…. Once, after a random click, however, I entered hxzq.com, and then “Huaxia zhiqing Forum,” “Random Talk” forum, and “Old Three Classes” forum. A brand-new world appeared in front of me. Isn’t this the home I have been earnestly searching for!42

Martial-arts Images of Online Communities

The third group of images is borrowed from the language of martial-arts fiction. The central image here is Rivers and Lakes. Epitomizing the martial artist’s image of the world, Rivers and Lakes refers to a world away from the established social and political order: a second world. It is a world of adventure, freedom, transgression, and divine justice, but also a world of betrayal, intrigue, and evil. The hero in this world strives for fame and honor by seeking to restore justice. The supreme code of behavior in Rivers and Lakes is therefore honor, embodied by xia, the knight-errant. The character-ideal of xia has been an important part of popular culture for thousands of years. It was first captured as early as in the Han dynasty by the historian Sima Qian, in his Records of the Grand Historian: “Their words were always sincere and trustworthy, and their actions always quick and decisive. They were true to what they promised, and without regard to their own persons, they would rush into dangers threatening others.”43 This ideal informs the modern-day martial-arts novel. As John Hamm puts it in his study of this modern genre:

The world of the Rivers and Lakes constitutes an activist alternative to the “hills and woods” (shanlin) of the traditional Daoist or Confucian recluse, equally removed from the seats of power but not content with quiet self-cultivation. The marginal terrain of the Rivers and Lakes, the creation of an alternative sociopolitical system, and the bandits’ chivalric imperative to “carry out the Way on Heaven’s behalf” (ti tian xing dao) all harbor a potential threat to the established order, traditionally conceptualized as comprehensive, hierarchic, and exclusively sanctioned by divine authority.44

Yet, as John Hamm also points out, the world of Rivers and Lakes is “structured around a fundamental opposition between the forces of good and the forces of evil.”45 Thus it is also a treacherous world of intrigue and evil.

For many Internet users, online communities (and cyberspace in general) are their Rivers and Lakes, where they seek freedom, adventure, and even a sense of heroism. The image of the Internet as Rivers and Lakes did not become popular until recent years. A book about the culture of Flash movies published in 2006, titled The Rivers and Lakes of the Flash Creators, compared the world of Flash makers to that of the Rivers and Lakes.46 In 2006, Sina named its tenth-anniversary celebrations “Ten Years of Rivers and Lakes.” A letter addressed to its community members contains the following passage:

Ten years—do you still remember those people and events in the Rivers and Lakes? … Those stories of the past—some may have been forgotten, some may be remembered for a long time and slowly become legends. Rivers and Lakes are full of stories. When people look back in the future, will they remember us? Making bricks,47 watering, quarreling—these are the three superb skills of the Rivers and Lakes. The world is yours to travel!48

A message posted in December 2007 in the BBS forums of oeeee.com published a list of sixty heroes for the year 2007 and compared them explicitly to martial-arts heroes.49 The message prefaced the list with the following statement: “The Internet is Rivers and Lakes. BBS forums are its battleground. Looking back on 2007, oeeee BBS forums were alive with gusty winds and clouds. One ID appeared after another in endless succession. Some died a hero’s death, others proudly stood. All sorts of people went on stage in full makeup.”50

The promotional statement for a popular Internet novel called Wangluo jianghu you [Travels in the Rivers and Lakes of the Internet] depicts the Internet as a world of good and evil, sacredness and seduction:

What is Rivers and Lakes?

Rivers and Lakes is a devil!

Rivers and Lakes is Dao!

Rivers and Lakes is blood!

What is the Internet?

The Internet is God!

The Internet is devil!51

The comparison of the Internet to Rivers and Lakes reflects current views of Chinese society. Some Chinese intellectuals have suggested that contemporary Chinese society is turning into jianghu—Rivers and Lakes.52 It is becoming lawless, where police officers collude with organized crime, local government is utterly corrupt, established institutions no longer function properly, and power and money dominate everything. In such a society, citizens must organize themselves for self-defense, justice, and freedom. It is against this background of a society turning into Rivers and Lakes that the following case study becomes particularly illuminating.

A Plea for Help Creates a Community of Compassion

Many cases of mobilization in online communities show that the values of freedom, solidarity, and justice motivate online activism and are reaffirmed in the process. One particularly influential and complicated case happened in 2005 and is known as the case of “selling my body to save mom” (mai shen jiu mu). The story started on September 15, 2005, when a post titled “Selling my body to save mom” appeared in a popular BBS forum in the Tianya communities. The author of the posting, whom I will call XY, claimed she was a twenty-year-old college student in Chongqing and that her father had died of liver disease when she was eleven years old. She explained that her mother was now also dying of liver disease and needed a liver transplant. She described in moving detail the hardships she and her mother had experienced in seeking medical treatment and pleaded for help at the end of the message: “How I hope some good-hearted people will save my mom!!! I’d rather sell myself!!! I would sell myself in any manner or I’m willing to work for him/her unconditionally after I graduate. I guarantee that my personal qualities are good. I pledge on my dignity and honor that this is a cry for help from the bottom of the heart of a college student to save the life of her dying mother.”53 She added two phone numbers and an e-mail address.

In her study of public sympathy in the 1930s, Eugenia Lean shows how the mediated outpourings of public sympathy “hailed into being” new forms of publics. The XY case involved a similar process. After she posted her plea for help, community members responded immediately. XY’s message appeared in “Tianya Chats” (Tianya zatan) at 20:23. The first response came at 20:48, which read: “Don’t lose hope. We will all be trying to figure out how to help you.” One minute later, another responded with the following: “We’ll all support you. There is hope.” And a third message, posted at 20:55, stated: “Young girl, be strong. Let us first publicize the information in other forums, to let others know of the girl’s situation.” Several posts asked XY to provide her bank-account information for receiving donations. Although some people cautioned about the possibility of swindling and requested verification of the information, the overwhelming sentiments were of sympathy and support. One person made a comment by citing a famous line from Qu Yuan’s poem: “Lamenting the many hardships of people’s lives, I often sigh and shed my tears.” Another wrote: “My mother is also ill, has cancer…. Let’s try together to let our mothers recover.” And finally: “I have great sympathy for you. Your filial heart is commendable. I am willing to do my little bit to help you.”54 Monetary donations immediately began to pour in. XY reportedly had received RMB 16,000 in donations by September 17. The local newspapers in Chongqing covered her story. Fundraising activities were launched both in her college and in her mother’s work-unit.55 On November 8, a message was posted on behalf of XY, which provided a detailed account of the donations she received. Altogether 217 people made donations, including Canadian and American dollars and euros sent from foreign banks. XY did not claim the foreign currency and left a few other small sums unclaimed. Other than that, the monetary donations she received added up to RMB 114,550.56

A Knight-errant Is Born in Cyberspace

While community members showered sympathy on XY, things took an unexpected turn on September 18, when a “Lan Lian’er” posted a message questioning the credibility of XY’s story. The author of the post claimed that he or she knew XY personally and that XY wore the newest models of Adidas and Nike shoes, used both a cellphone and a “Little Smart” phone, owned contact lenses priced at RMB 500, and mixed with people of dubious character.57 The posting suggested that XY was not as desperate as she pretended to be. Lan Lian’er’s post plunged the community into a crisis. If indeed XY was deceiving the community, it amounted to an abuse of the enormous trust and sympathy people had extended to her. The values of the community were under threat. One message posted on September 30, 2005, proposed that the community should select ten trustworthy members to go to Chongqing to find out the truth, because “We can’t bear any more living in a society full of deception and with no one you can trust.”58

While no such selection took place, an Internet user known as “Eightcent Meal” (ba fen zhai), or “Eight-cent” for short, took it upon himself to undertake an investigation. Born in 1975, he worked as a Web editor in Shenzhen. In two messages posted on September 30 and October 4 respectively, he asked XY to publish her account and turn over the donations to a charity organization for management. Receiving no response, Eight-cent decided to travel to Chongqing to investigate. He explained:

I thought about this issue carefully and felt that goodwill must not be allowed to be trampled upon, that goodwill action must not be allowed to be violated. The only solution is to do a field investigation, to find out the truth and restore goodwill…. I thought about the goodhearted netfriends in Tianya. They have put this valuable goodwill into action. They talked, and then they acted. This was a qualitative change, not an easy one! What I didn’t expect was that these energies grew so strong. The surging passions compelled people to voluntarily organize into teams. Some supported the idea of an investigation; others were ready to cover the expenses. In a world that some consider as virtual, true feelings of human care are so real…. And yet the [XY] incident worried and angered these good-hearted people…. Only an independent investigation can offer a final solution.59

In a response on October 8, XY extended an invitation for community members to investigate. Eight-cent flew to Chongqing on October 9, where he was joined by two local members of the Tianya online community and another who had come from Shanghai. They visited XY’s college, her dorm, and her family’s apartment, interviewed XY and her mother, and studied her bank account. They found that she was not forthright with her donations and that there were loopholes in her story.60 Back in Shenzhen, Eightcent began to publish his report, which appeared in nine installments in the Tianya communities from October 19 to October 22.

The publishing of Eight-cent’s investigation report energized the community. There was an outpouring of posts in praise of Eight-cent and his fellow investigator Jin Guanren for undertaking a heroic act at their own expense. The posts I downloaded for the period from October 19, 2005 (when Eight-cent published the first installment), to December 23, 2005 (the last day of the cached postings on Tianya), run up to 1,960 single-spaced pages. In praising Eight-cent and Jin Guanren, members articulated and reaffirmed the values of their ideal community. Some praised their compassion: “What a compassionate deed! A great contribution to the institutionalization of Internet charity in the future (2005–10–19 23:16:51).”61 Others called them xia (knight-errants) and lauded their courage, bravery, and strength: “I respect Eight-cent and Jin Guanren for their spirit and bravery of a knight-errant (2005–10–21 14:08:02).” Some postings used gendered language and spoke of the investigators as exemplars of masculinity. One acclaims: “Eight-cent my cute brother is truly a knight-errant!!!!!!!! (2005–10–23 2:04:59).” And another: “Big Brother Jin and Brother Eight-cent are both true men. Men who have the courage to do what they want to do (2005–10–19 23:26:46).”

Many commentators said they saw hope in a corrupt world because there were still brave people fighting for justice. Said one: “I admire those who made the field trip. You made me feel that there is still justice in this world (2005–10–19 23:47:31).” Another elaborated:

I agree that we should contribute money to cover Eight-cent’s and Jin Guanren’s salary loss due to absence from work as well as their travel and investigation expenses. I pay my highest respects to Eight-cent and Jin Guanren for seeking justice in the spirit of knight-errants!!! I propose all netfriends in “Tianya Chats” stand, let go of the mouse, and clap hands warmly for three minutes to welcome the triumphant return of the two great knight-errants!!! (2005–10–20 00:25:54)

Privacy and Trust

The praise of Eight-cent continued for days. Each new installment of his investigative report generated endless expressions of admiration and enthusiastic discussions, which branched into a broad range of topics touching on major critical issues in contemporary society, from trust and justice to charity, filial piety, privacy, and sexuality. People became aware of the historical significance of this event. One person suggested that this may well be one of the most important Internet incidents in 2005 and perhaps even a major incident in the history of Chinese Internet culture.62

These excited discussions about justice, heroism, selflessness, trust, and charity revealed a strong yearning for the purity of the community and, indeed, an impulse to purify the community. It was in the middle of these discussions that the most radical forms of action took place. In the name of seeking justice and exposing XY’s deceptive behavior, hackers accessed XY’s personal e-mail and chat records on qq.com and posted them online. The hackers were immediately hailed as xia—heroes of the Rivers and Lakes. Yet there were also dissenting voices that questioned the hacking of XY’s personal information. In a posting that ran over two thousand Chinese characters, one person argued:

I should note that the QQ chat records basically documented [XY] and her mother’s original intentions and their psychology in the process of implementing their plans…. We denounce them morally, because our moral values reflect social equity and justice. These values must constrain the immoral means of action in reality that put personal interests above everything else. [XY] and her mother’s behavior basically damaged the equal relations of all of us in economic interests and basic rights and violated the rights of those who are really in need of help. This is my personal view of the nature of this matter.

But is [XY] and her mother’s behavior so wicked as to be unpardonable?… I wish to condemn those smart knights-errant [xia] who broke into [XY]’s computer accounts. Shouldn’t we also denounce the methods you used? … If today you hacked [XY]’s computer accounts and exposed her privacy without being condemned, then tomorrow you will invade more people’s computers and expose more people’s privacy to broad daylight…. I firmly believe that we should not accept the truth or results that are obtained using illegitimate means.63

The debates over privacy and justice were intense. They brought up multiple concerns beyond the issues of justice and trust. In the middle of these debates came the news of XY’s mother’s death during surgery on October 24. The news threw the community into another crisis. Some members accused Eight-cent of hastening her mother’s death because of his relentless effort to expose her. They claimed that XY’s mother underwent surgery instead of awaiting a liver transplant because she knew she could die from the surgery and she wanted to clear her daughter’s name with her death. Others condoled the death but stood by Eight-cent, insisting that the issue was about trust. One person defended Eight-cent, arguing that although many people talked about finding out the truth, he alone took the trouble of doing it by traveling to Chongqing for a field investigation. For this reason, many people insisted that XY should still publish an accounting of the donations she had received. One person argued that if XY did not publish a detailed account of the donations, she would be betraying both the trust of those who had donated money and of the entire Tianya community, where she had pleaded for help and met with an outpouring of sympathy and support.64 Another wrote two simple words: “Support trust (2005–10–24 11:19:13).” Another elaborated:

Some people thought, now that [XY]’s mother had passed away, in order not to put salt on [XY]’s wound, it is no longer necessary to hold her accountable. This is a humanitarian position. I believe that [the incident of] “selling my body to save mom” is emblematic of the new social phenomenon of Internet charity. To give a clear account of the event, to draw experience and lessons from it, to explore a feasible path for Internet charity in the future, to provide assistance to more people who are in need of it—all this makes it imperative to have a clear result.65

For Eight-cent’s supporters, therefore, the crux of the matter was to repair and reestablish trust in a community that had initially acted together on trust and then was threatened by its violation. On November 8, a message was posted in Tianya on behalf of XY, providing a detailed accounting of the donations. Of the RMB 114,550 she received, 42,707.06 was spent on her mother’s surgery. The remaining 71,842.94 was turned over to a local foundation for children suffering from leukemia.66 The event quieted down afterward.

Altruistic Action in an Egoistic Society

For several reasons, the XY incident is an important case of online activism. First, it exemplifies the complex dynamics in the mutual constitution of online community and Internet activism. Here, the Tianya community provided a social structure for articulating social concerns and organizing collective action. The contention both affirmed the values of a moral community and exposed some of its weaknesses. Second, the issue of Internet-based charity is relatively new and constitutes part of the broader landscape of the proliferation of issue areas in contemporary activism. Charity has always existed; the number of charity organizations, both official and nonofficial, has increased. Yet the use of the Internet as a platform for voluntary, self-organized charitable action is new. Third, the forms of action are exemplary in their multidimensional dynamics and persuasive means of action. The case involved the interfacing of online and offline action and interactions among multiple actors, including the individual and the collective, the Internet and the official media. The interfacing of online and offline action is particularly significant, because it shows both that online communities with strong collective sentiments and solidarity can generate effective offline action and that offline action can contribute to the regeneration of online communities.

Fourth, the nature of the issue suggests that this Internet-based charity action has a different politics than is commonly associated with social movements in China. To begin with, it is a powerful symbolic statement about the social crisis in China today. As such, it is a critique of social reality. Two aspects of the social crisis come across most strikingly. One is the acute need for social assistance for the weak, the poor, and the sick. XY’s plea for help reflects the depth of desperation; its resonance with the community reflects the prevalence of the crisis. The other aspect of the social crisis that is exposed in this case is the badly damaged condition of trust in Chinese society. Throughout the incident, a central concern of community members was the restoration of trust.

Further, the case exposes the sorry condition of China’s state-welfare system. Community members frequently mentioned the lack of state institutions of social welfare and the inability of existing institutions to tackle the scope of the problems. Taking a very different view of the government than in Western liberal democracies, they argued that it was the government’s responsibility to take care of its citizens. One post cited a spokesperson from a charity organization in Chongqing as saying that it was illegal for their organization to take over the donations to XY because only a few national-level organizations were authorized to accept donations.67 Another explained that he or she would not make a donation because the root of the problem lay in the government’s lack of social-welfare institutions and its poor performance.68

Finally, this is a case about the coming to consciousness of an active and participatory citizenship in the Internet age. In response to an Internet plea for help, members of the Tianya communities mobilized swiftly and participated actively. They used their own actions to show that where government fails, citizens will take it upon themselves to reconstruct community and morality. When 217 people donated money in response to a BBS posting, it was a strong statement that they still had faith in a society threatened by the collapse of morality and trust. And if only two of them traveled long distances to find out the truth, they were not alone in their cause. Their action drew support, inspired the community, and brought into relief values that are under assault in contemporary society—values of care, sympathy, trust, responsibility. These are the values of citizenship. Ultimately, the larger significance of this and other cases lies in the affirmation of these values.69

In his study of contemporary social movements, Alberto Melucci examines altruistic action as a peculiar new form of social movement, one “characterized by a voluntary bond of solidarity among those who participate in it, and by the fact that they do not derive any direct economic benefit from that participation.”70 He considers such action as social movements because of its symbolic dimension, “where conflictual forms of behavior are directed against the processes by which dominant cultural codes are formed. It is through action itself that the power of the languages and signs of technical rationality are challenged. By its sheer existence, such action challenges power, upsets its logic, and constructs alternative meanings.”71

The case I studied dovetails with this notion of collective action. It is the manifestation of altruistic collective action under conditions of Chinese modernity. For some, even to talk about altruistic action in an increasingly commercialized and egoistic society is utopian thinking. The generation brought up in a socialist culture of altruism retains only memories of their ideals.72 A new “Generation Me” has emerged, with all of its narcissistic aspirations.73 All this happens in the middle of social polarization and fragmentation. Perhaps it is precisely from the soil of the disillusionment caused by these contradictions that a utopian impulse begins to rise. Online activism is one of its most powerful expressions, but by no means is it the only expression. The utopian impulse is pervasive in Chinese life. As Jameson might put it, it reveals itself in the daily life of things and people through such utopian figures as beauty, wholeness, energy, perfection, and, I might add, a yearning for justice, trust, and solidarity.

Conclusion

This chapter argues that online communities are where people exert their work of the imagination. One of the most important products of this imaginative work is what Giddens refers to as utopian realism and what Jameson calls the utopian impulse. In the numerous Chinese online communities may be detected a strong yearning for belonging, freedom, and justice. The yearning emerges against the historical background of an increasingly fractured Chinese society and expresses both strong critiques of Chinese reality and aspirations for an alternative world. This yearning is expressed both in language and action. The process of its articulation turns online communities into moral spaces74 where idealized visions of society are tested, contested, and affirmed. By showing how utopian values both activate community and compel moral action, this chapter shows how Chinese netizens affirm the positive value of utopia in a dystopian age. They affirm the possibility of change and alternatives. It is in this sense that this utopian impulse is realistic.

The online communities are not free of their own problems. A much discussed issue is “flaming.” The Chinese term often used to label this behavior is wangluo yuyan baoli, “Internet verbal violence.” When I visited Beijing in the summer of 2007, there was much talk in the Chinese mainstream media about how Chinese cyberspace was plagued by verbal violence and that the Internet, because of its anonymity and interactivity, must be held responsible for it. This line of argument typically leads to the conclusion that the government should tighten Internet control. The ideological underpinning of this argument is as clear as the argument is wrong. First, the argument is based on an exaggerated reality. Online verbal violence—call it violent talk—is not as prevalent as is often depicted.75 In the BBS forums I frequent, sociable and engaging conversations and discussions are much more common. People do often use more curse words when it comes to protesting against social injustices. Given the situation and the nature of the discussion, this could hardly be otherwise. After all, they are engaged in contentious activities. A more serious flaw in this argument is that it puts the blame on the medium, as if people would automatically engage in verbal violence when they are given the freedom to talk. It ignores the larger picture of Chinese reality, where not only violent talk but also violent forms of collective action such as demonstrations and riots have been on the rise. If violent talk has indeed increased in cyberspace, then it is rooted in the same conditions that have led to the frequent protest activities in the streets. Crises of communication are rooted in crises of community.

The utopian impulse in Chinese online communities does have a somber tone, which conveys the crisis of community. The martial-arts image of Rivers and Lakes, perhaps the most common metaphor of the Chinese Internet today, is an image of individual heroism in a world torn between good and evil. It is a metaphor that captures at once an ideal and a reality. The reality is not just about the Internet but also about society. The reality of Chinese society, like the Internet, has a dark side. Like the Internet, Chinese society is becoming Rivers and Lakes, where the weakening of institution, culture, and community appears to be leading to a state of lawlessness,76 where citizens are increasingly called upon, as martial-arts heroes once were, to restore trust, justice, and morality. The challenges are as evident as is the urgency.

Hope lies in the reconstruction of community. Writing of new communal forms at the transnational and subnational levels, Arjun Appadurai argues that “they are communities in themselves but always potentially communities for themselves, capable of moving from shared imagination to collective action.”77 This chapter shows one instance of this move, when members of an online community not only attempted to collectively imagine new values but also tried to put them into practice. The utopian impulse in Chinese online communities is a yearning for a moral community.