Cimetière du Père Lachaise

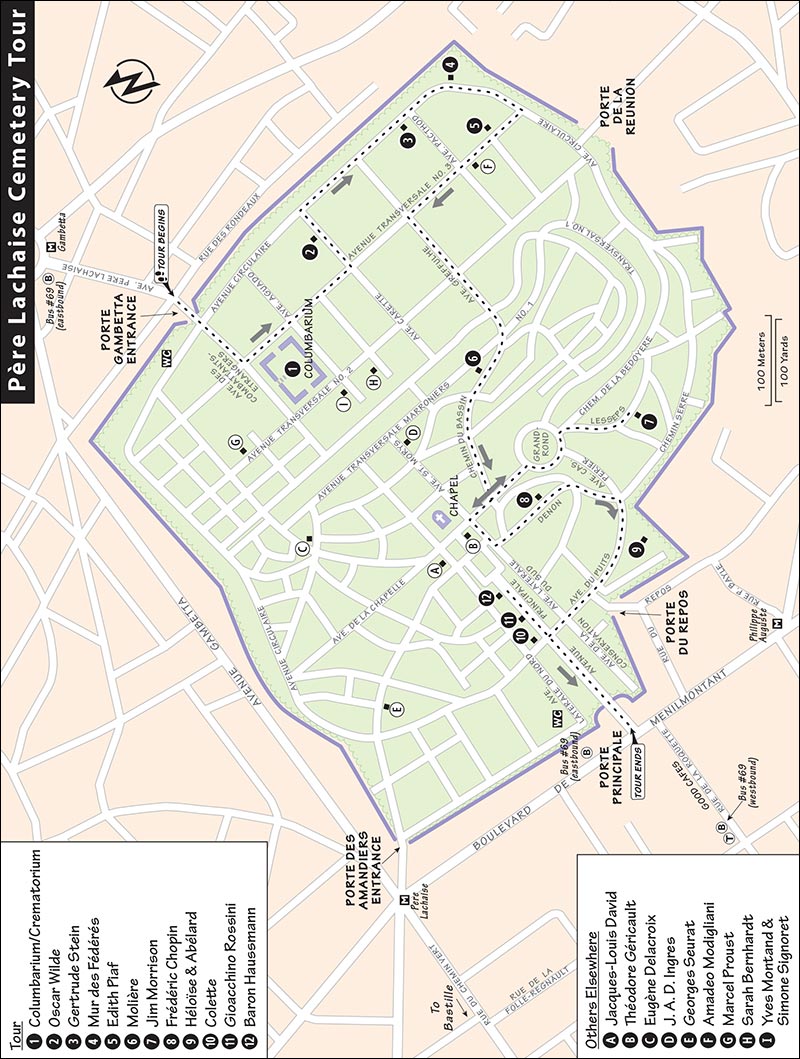

Map: Père Lachaise Cemetery Tour

Héloïse (c. 1101-1164) and Abélard (1079-1142)

Héloïse (c. 1101-1164) and Abélard (1079-1142)

Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868)

Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868)

Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann (1809-1891)

Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann (1809-1891)

Enclosed by a massive wall and lined with 5,000 trees, the peaceful, car-free lanes and dirt paths of Père Lachaise cemetery encourage parklike meandering. Named for Father (Père) La Chaise, whose job was listening to Louis XIV’s sins, the cemetery is relatively new, having opened in 1804 to accommodate Paris’ expansion. Today, this city of the dead (pop. 70,000) still accepts new residents, but real estate prices are sky high (a 21-square-foot plot costs more than €11,000).

The 100-acre cemetery is big and confusing, with thousands of graves and tombs crammed every which way, and only a few pedestrian pathways to help you navigate. The maps available from a nearby florist or from street vendors can help guide your way (see below), but you’re better off taking my tour as you play grave-hunt with the cemetery’s other visitors. This walk takes you on a one-way tour between two convenient Métro/bus stops (Gambetta and Père Lachaise), connecting a handful of graves from some of this necropolis’ best-known residents.

(See “Père Lachaise Cemetery Tour” map, here.)

Cost: Free.

Hours: Mon-Fri 8:00-18:00, Sat 8:30-18:00, Sun 9:00-18:00, until 17:30 in winter.

Getting There: Take bus #69 eastbound to the end of the line at Place Gambetta (see the Bus #69 Sightseeing Tour chapter), or ride the Métro to the Gambetta stop (not to the Père Lachaise stop), exit at Gambetta Métro, and take sortie #3 (Père Lachaise exit). From Place Gambetta, it’s a two-block walk past McDonald’s and up Avenue du Père Lachaise to the cemetery.

Information: Maps are sold at J Poulain & Fils, a florist across from the Porte Gambetta entrance (about €2), or from wandering street vendors for a little more. An unofficial website, www.pere-lachaise.com, has a searchable map. Tel. 01 55 25 82 10.

Length of This Tour: Allow 1.5 hours for this walk and another 30 minutes for your own detours. Bring good walking shoes for the rough, cobbled streets.

Services: WCs are at the start of this tour, just inside the Porte Gambetta entrance (up to the right), and at the end of this tour, to the right just before you exit Porte Principale.

Eating: You’ll pass several cafés and a small grocery shop between Place Gambetta and the cemetery. After the tour, you can walk downhill from the cemetery on Rue de la Roquette to a gaggle of lively, affordable cafés on the right side of the street, near the return stop for bus #69.

Starring: Oscar Wilde, Edith Piaf, Gertrude Stein, Molière, Jim Morrison, Frédéric Chopin, Héloïse and Abélard, Colette, and Rossini.

From the Porte Gambetta entrance, we’ll walk roughly southwest (mostly downhill) through the cemetery. At the end of the tour, we’ll exit Porte Principale onto Boulevard de Ménilmontant, near the Père Lachaise Métro entrance and another bus #69 stop. (You could follow the tour heading the other direction, but it’s not recommended—it’s confusing, and almost completely uphill.)

Be sure to keep referring to the map on here, and follow street signs posted at intersections. The layout of the cemetery makes an easy-to-follow tour impossible. It’s a little easier if you buy a more detailed map to use along with our rather general one. Be patient, make a few discoveries of your own, and ask passersby for graves you can’t locate.

(See “Père Lachaise Cemetery Tour” map, here.)

• Entering the cemetery at the Porte Gambetta entrance, walk straight up Avenue des Combattants Étrangers past World War memorials, cross Avenue Transversale No. 3, pass the first building, and look left to the...

Columbarium / Crematorium

Columbarium / CrematoriumMarked by a dome with a gilded flame and working chimneys on top, the columbarium sits in a courtyard surrounded by about 1,300 niches, small cubicles for cremated remains, often decorated with real or artificial flowers.

Beneath the courtyard (steps leading underground) are about 12,000 smaller niches, including one for Maria Callas (1923-1977), an American-born opera diva known for her versatility, flair for drama, and affair with Aristotle Onassis (niche #16258, down aisle J).

• Turn around and walk back to the intersection with Avenue Transversale No. 3. Turn right, heading southeast on the avenue, turn left on Avenue Carette, and walk half a block to the block-of-stone tomb (on the left) with heavy-winged angels trying to fly.

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900)

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900)The writer and martyr to homosexuality is mourned by “outcast men” (as the inscription says) and by wearers of heavy lipstick, who used to cover the tomb and the angels’ emasculated privates with kisses. (Now the tomb is behind glass, which has not stopped committed kissers.) Despite Wilde’s notoriety, an inscription says, “He died fortified by the Sacraments of the Church.” There’s a short résumé scratched (in English) into the back side of the tomb. For more on Wilde and his death in Paris, see here.

“Alas, I am dying beyond my means.”

—Oscar Wilde

• Continue along Avenue Carette and turn right (southeast) down Avenue Circulaire. Almost two blocks down, you’ll reach Gertrude Stein’s unadorned, easy-to-miss grave (on the right, just before a beige-yellow stone structure—if you reach Avenue Pacthod, you’ve passed it by about 30 yards).

Gertrude Stein (1874-1946)

Gertrude Stein (1874-1946)While traveling through Europe, the twentysomething American dropped out of med school and moved to Paris, her home for the rest of her life. She shared an apartment at 27 Rue de Fleurus (a couple of blocks west of Luxembourg Garden) with her brother Leo and, later, with her life partner, Alice B. Toklas (who’s also buried here, see gravestone’s flipside). Every Saturday night, Paris’ brightest artistic lights converged chez vingt-sept (at 27) for dinner and intellectual stimulation. Picasso painted her portrait, Hemingway sought her approval, and Virgil Thompson set her words to music.

America discovered “Gerty” in 1933 when her memoirs, the slyly titled Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, hit the best-seller list. After 30 years away, she returned to the United States for a triumphant lecture tour. Her writing is less well known than her persona, except for the oft-quoted, “A rose is a rose is a rose.”

Stein’s last words: When asked, “What is the answer?” she replied, “What is the question?”

• Ponder Stein’s tomb again and again and again, and continue southeast on Avenue Circulaire to where it curves to the right. Emaciated statues remember victims of the concentration camps and Nazi resistance heroes. Pebbles on the tombstones represent Jewish prayers. About 50 yards past Avenue Pacthod, veer left off the road where you see the green Avenue Circulaire street sign to find the wall marked Aux Morts de la Commune.

Mur des Fédérés

Mur des FédérésThe “Communards’ Wall” marks the place where the quixotic Paris Commune came to a violent end.

In 1870, Prussia invaded France, and the country quickly collapsed and surrendered—all except the city of Paris. For six months, through a bitter winter, the Prussians laid siege to the city. Defiant Paris held out, even opposing the French government, which had fled to Versailles and was collaborating with the Germans. Parisians formed an opposition government that was revolutionary and socialist, called the Paris Commune.

The Versailles government sent French soldiers to retake Paris. In May of 1871, they breached the west walls and swept eastward. French soldiers fought French citizens, and tens of thousands died during a bloody week of street fighting (La Semaine Sanglante). The remaining resisters holed up inside the walls of Père Lachaise and made an Alamo-type last stand before they were finally overcome.

At dawn on May 28, 1871, the 147 Communards were lined up against this wall and shot by French soldiers. They were buried in a mass grave where they fell. With them the Paris Commune died, and the city entered five years of martial law.

• Return to the road, continue to the next (unmarked) street, Avenue Transversale No. 3, and turn right. A half-block uphill, Edith Piaf’s grave is on the right. It’s one grave off the street, behind a white tombstone with a small gray cross (Salvador family). Edith Gassion-Piaf rests among many graves. Hers is often adorned with photos, fresh flowers, and love notes.

Edith Piaf (1915-1963)

Edith Piaf (1915-1963)A child of the Parisian streets, Piaf was raised in her grandma’s bordello and her father’s traveling circus troupe. The teenager sang for spare change in Paris’ streets, where a nightclub owner discovered her. Waif-like and dressed in black, she sang in a warbling voice under the name “La Môme Piaf” (The Little Sparrow). She became the toast of pre-WWII Paris society.

Her offstage love life was busy and often messy, including a teenage pregnancy (her daughter is buried along with her, in a grave marked Marcelle Dupont, 1933-1935), a murdered husband, and a heartbreaking affair with costar Yves Montand.

With her strong but trembling voice, she buoyed French spirits under the German occupation, and her most famous song, “La Vie en Rose” (The Rosy Life) captured the joy of postwar Paris. In her personal life she struggled with alcohol, painkillers, and poor health, while onstage she sang, “Non, je ne regrette rien” (“No, I don’t regret anything”).

• From Edith Piaf’s grave, continue uphill, cross Avenue Pacthod, and turn left on the next street, Avenue Greffulhe. Follow Greffulhe straight (even when it narrows) until it dead-ends at Avenue Transversale No. 1. Cross the street and venture down a dirt section that veers slightly to the right, then make a hard right onto another dirt lane named Chemin Molière et La Fontaine. Molière lies 30 yards down, on the right side of the street, just beyond the highest point of this lane.

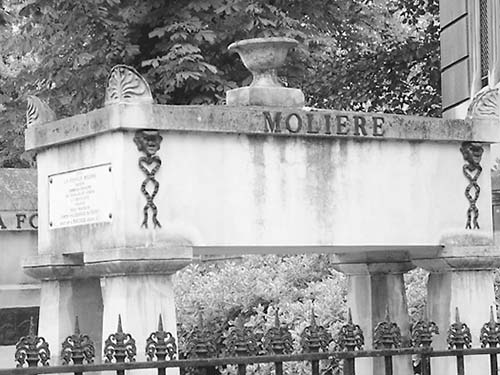

Molière (1622-1675)

Molière (1622-1675)In 1804, the great comic playwright was the first to be reburied in Père Lachaise, a publicity stunt that gave instant prestige to the new cemetery.

Born in Paris, Molière was not of noble blood, but as the son of the king’s furniture supervisor, he had connections. The 21-year-old Molière joined a troupe of strolling players, who ranked very low on the social scale, touring the provinces. Twelve long years later, they returned to Paris to perform before Louis XIV. Molière, by now an accomplished comic actor, cracked the king up. He was instantly famous—writing, directing, and often starring in his own works. He satirized rich nobles, hypocritical priests, and quack doctors, creating enemies in high places.

On February 17, 1675, an aging Molière went on stage in the title role of his latest comedy, The Imaginary Invalid. Though sick, he insisted he had to go on, concerned for all the little people. His role was of a hypochondriac who coughs to get sympathy. The deathly ill Molière effectively faked coughing fits...which soon turned to real convulsions. The unaware crowd roared with laughter while his fellow players fretted in the wings.

In the final scene, Molière’s character becomes a doctor himself in a mock swearing-in ceremony. The ultimate trouper, Molière finished his final line—“Juro” (“I accept”)—and collapsed while coughing blood. The audience laughed hysterically. He died shortly thereafter.

Irony upon irony for the master of satire: Molière—a sick man whose doctors thought he was a hypochondriac—dies playing a well man who is a hypochondriac, succumbing onstage while the audience cheers.

Molière lies next to his friend and fellow writer, La Fontaine (1621-1695), who wrote a popular version of Aesop’s Fables.

“We die only once, and for such a long time.”

—Molière

• Continue downhill on Chemin Molière et La Fontaine (which becomes the paved Chemin du Bassin), and turn left where it ends on Avenue de la Chapelle. This leads to the Rond Point roundabout intersection.

Cross Carrefour Rond Point and continue straight (opposite where you entered, on unmarked Chemin de la Bédoyère). Just a few steps along, turn right onto Chemin Lauriston. Keep to the left at the fork (now on Chemin de Lesseps), and look (immediately) for the temple on the right with three wreaths. Jim Morrison lies just behind, often with a personal security guard. You can’t miss the commotion.

Jim Morrison (1943-1971)

Jim Morrison (1943-1971)An American rock star has perhaps the most visited tomb in the cemetery. An iconic, funky bust of the rocker, which was stolen by fans, was replaced with a more toned-down headstone. Even so, Morrison’s faithful still gather here at all hours. The headstone’s Greek inscription reads: “To the spirit (or demon) within.” Graffiti-ing nearby tombs, fans write: “You still Light My Fire” (referring to Jim’s biggest hit), “Ring my bell at the Dead Rock Star Hotel,” and “Mister Mojo Risin’” (referring to the legend that Jim faked his death and still lives today).

Jim Morrison—singer for the popular rock band The Doors (named for the “Doors of Perception” they aimed to open)—arrived in Paris in the winter of 1971. He was famous, notorious for his erotic onstage antics, and now a burned-out alcoholic. Paris was to be his chance to leave celebrity behind, get healthy, and get serious as a writer.

Living under an assumed name in a nondescript sublet apartment near Place de la Bastille (see here), he spent his days as a carefree artist. He scribbled in notebooks at Le Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots ( see the Left Bank Walk chapter), watched the sun set from the steps of Sacré-Cœur, visited Baudelaire’s house, and jammed with street musicians. He drank a lot, took other drugs, gained weight, and his health declined.

see the Left Bank Walk chapter), watched the sun set from the steps of Sacré-Cœur, visited Baudelaire’s house, and jammed with street musicians. He drank a lot, took other drugs, gained weight, and his health declined.

In the wee hours of July 3, he died in his bathtub at age 27, officially of a heart attack, but likely from an overdose. (Any police investigation was thwarted by Morrison’s social circle of heroin users, leading to wild rumors surrounding his death.)

Jim’s friends approached Père Lachaise Cemetery about burying the famous rock star there, in accordance with his wishes. The director refused to admit him, until they mentioned that Jim was a writer. “A writer?” he said, and he found a spot.

“This is the end, my only friend, the end.”

—Jim Morrison

• Return to Rond Point, cross it, and retrace your steps—sorry, but there are no straight lines connecting these dead geniuses. Retrace your steps up Avenue de la Chapelle. At the intersection with the small park and big chapels, turn left onto Avenue Laterale du Sud. Walk down two sets of stairs and turn left onto narrow Chemin Denon. “Fred” Chopin’s grave—usually adorned with flowers, burning candles, and his fans—is about 80 yards down on the left.

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)Fresh-cut flowers and geraniums on the gravestone speak of the emotional staying power of Chopin’s music, which still connects souls across the centuries. A muse sorrows atop the tomb, and a carved relief of Chopin in profile captures the delicate features of this sensitive artist.

The 21-year-old Polish pianist arrived in Paris, fell in love with the city, and never returned to his homeland (which was occupied by an increasingly oppressive Russia). In Paris, he could finally shake off the “child prodigy” label and performance schedule he’d lived with since age seven. Cursed with stage fright (“I don’t like concerts. The crowds scare me, their breath chokes me, I’m paralyzed by their stares...”) and with too light a touch for big venues, Chopin preferred playing at private parties for Paris’ elite. They were wowed by his technique; his ability to make a piano sing; and his melodic, soul-stirring compositions. Soon he was recognized as a pianist, composer, and teacher and even idolized as a brooding genius. He ran in aristocratic circles with fellow artists, such as pianist Franz Liszt, painter Delacroix, novelists Victor Hugo and Balzac, and composer Rossini. (All but Liszt and Hugo lie in Père Lachaise.)

Chopin composed nearly 200 pieces, almost all for piano, in many different styles—from lively Polish dances to the Bach-like counterpoint of his Preludes to the moody, romantic Nocturnes.

In 1837, the quiet, refined, dreamy-eyed genius met the scandalous, assertive, stormy novelist George Sand ( see the Left Bank Walk chapter). Sand was swept away by Chopin’s music and artistic nature. She pursued him, and sparks flew. Though the romance faded quickly, they continued living together for nearly a decade in an increasingly bitter love-hate relationship. When Chopin developed tuberculosis, Sand nursed him for years (Chopin complained she was killing him). Sand finally left, Chopin was devastated, and he died two years later at age 39. At the funeral, they played perhaps Chopin’s most famous piece, the Funeral March (it’s that 11-note dirge that everyone knows). The grave contains Chopin’s body, but his heart lies in Warsaw, embedded in a church column.

see the Left Bank Walk chapter). Sand was swept away by Chopin’s music and artistic nature. She pursued him, and sparks flew. Though the romance faded quickly, they continued living together for nearly a decade in an increasingly bitter love-hate relationship. When Chopin developed tuberculosis, Sand nursed him for years (Chopin complained she was killing him). Sand finally left, Chopin was devastated, and he died two years later at age 39. At the funeral, they played perhaps Chopin’s most famous piece, the Funeral March (it’s that 11-note dirge that everyone knows). The grave contains Chopin’s body, but his heart lies in Warsaw, embedded in a church column.

“The earth is suffocating. Swear to make them cut me open, so that I won’t be buried alive.”

—Chopin, on his deathbed

• Continue walking down Chemin Denon as it curves down and to the right. Stay left at the Chemin du Coq sign and walk down to Avenue Casimir Perier. Turn right and walk downhill 30 yards, looking to the left, over the tops of the graves, for a tall monument that looks like a church with a cross perched on top. Under this stone canopy lie...

Héloïse (c. 1101-1164) and Abélard (1079-1142)

Héloïse (c. 1101-1164) and Abélard (1079-1142)Born nearly a millennium ago, these are the oldest residents in Père Lachaise, and their story is timeless.

In an age of faith and Church domination of all aspects of life, the independent scholar Peter Abélard dared to say, “By questioning, we learn truth.” Brash, combative, and charismatic, Abélard shocked and titillated Paris with his secular knowledge and reasoned critique of Church doctrine. He set up a school on the Left Bank (near today’s Sorbonne) that would become the University of Paris. Bright minds from all over Europe converged on Paris, including Héloïse, the brainy niece of the powerful canon of Notre-Dame.

Abélard was hired (c. 1118) to give private instruction to Héloïse. Their intense intellectual intercourse quickly flared into physical passion and a spiritual bond. They fled Paris and married in secret, fearing the damage to Abélard’s career. After a year, Héloïse gave birth to a son (named Astrolabe), and the news got out, soon reaching Héloïse’s uncle. The canon exploded, sending a volley of thugs in the middle of the night to Abélard’s bedroom, where they castrated him.

Disgraced, Abélard retired to a monastery and Héloïse to a convent, never again to live as man and wife. But for the next two decades, the two remained intimately connected by the postal service, exchanging letters of love, devotion, and intellectual discourse that survive today. (The dog at Abélard’s feet symbolizes their fidelity to each other.) Héloïse went on to become an influential abbess, and Abélard bounced back with some of his most critical writings. (He was forced to burn his Theologia in 1121 and was on trial for heresy when he died.) Abélard used logic to analyze Church pronouncements—a practice that would flower into the “scholasticism” accepted by the Church a century later.

When they died, the two were buried together in Héloïse’s convent and were later laid to rest here in Père Lachaise. The canopy tomb we see today (1817) is made out of stones from both Héloïse’s convent and Abélard’s monastery.

“Thou, O Lord, brought us together, and when it pleased Thee, Thou hast parted us.”

—From a prayer of Héloïse and Abélard

• Continue walking downhill along Avenue Casimir Perier, and keep straight as it merges into Avenue du Puits (passing the exit to the left). Stay the course until you cross Avenue Principale, the street at the cemetery’s main entrance. Cross Principale to find Colette’s grave (third grave from corner on right side).

Colette (1873-1954)

Colette (1873-1954)France’s most honored female writer led an unconventional life—thrice married and often linked romantically with other women—and wrote about it in semi-autobiographical novels. Her first fame came from a series of novels about naughty teenage Claudine’s misadventures. In her 30s, Colette went on to a career as a music hall performer, scandalizing Paris by pulling a Janet Jackson onstage. Her late novel, Gigi (1945)—about a teenage girl groomed to be a professional mistress, who blossoms into independence—became a musical film starring Leslie Caron and Maurice Chevalier (1958). Thank heaven for little girls!

“The only misplaced curiosity is trying to find out here, on this side, what lies beyond the grave.”

—Colette

• Take a few steps back to Avenue Principale and go uphill a half-block. On the left, find Rossini, with Haussmann a few graves up.

Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868)

Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868)Dut. Dutta-dut. Dutta dut dut dut dut dut dut dut dut, dut dut dut dut dut dut dut dut...

The composer of the William Tell Overture (a.k.a. the Lone Ranger theme) was Italian, but he moved to Paris (1823) to bring his popular comic operas to France. Extremely prolific, he could crank out a three-hour opera in weeks, including the highly successful Barber of Seville (based on a play by Pierre Beaumarchais, who is also buried in Père Lachaise). When Guillaume Tell debuted (1829), Rossini, age 37, was at the peak of his career as an opera composer.

Then he stopped. For the next four decades, he never again wrote an opera and scarcely composed anything else. He moved to Italy, went through a stretch of bad health, and then returned to Paris, where his health and spirits revived. He even wrote a little music in his old age. Rossini’s impressive little sepulcher is empty, as his remains were moved to Florence.

• Four graves uphill, find...

Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann (1809-1891)

Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann (1809-1891)(Look through the green door long enough for your eyes to dilate.) Love him or hate him, Baron Haussmann made the Paris we see today. In the 1860s, Paris was a construction zone, with civil servant Haussmann overseeing the city’s modernization. Narrow medieval lanes were widened and straightened into broad, traffic-carrying boulevards. Historic buildings were torn down. Sewers, bridges, and water systems were repaired. Haussmann rammed the Boulevard St. Michel through the formerly quaint Latin Quarter (as part of Emperor Napoleon III’s plan to prevent revolutionaries from barricading narrow streets). The Opéra Garnier, Bois de Boulogne park, and avenues radiating from the Arc de Triomphe were all part of Haussmann’s grand scheme, which touched 60 percent of the city. How did he finance it all? That’s what the next government wanted to know when they canned him.

Have you seen enough dead people? To leave the cemetery, return downhill on Avenue Principale and exit onto Boulevard de Ménilmontant. The Père Lachaise Métro stop is one long block to the right. To find the bus #69 stop heading west to downtown, cross Boulevard de Ménilmontant and walk downhill on the right side of Rue de la Roquette; the stop is four blocks down, on the right-hand side.