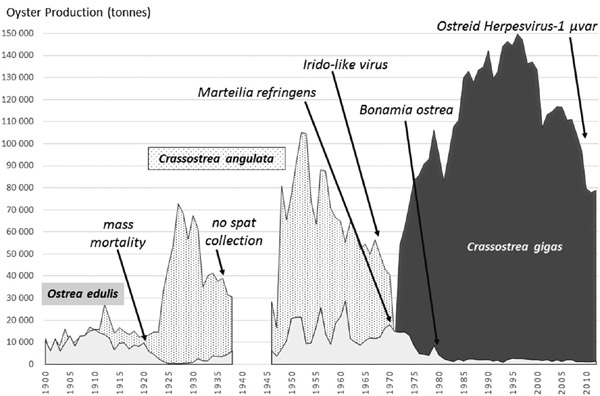

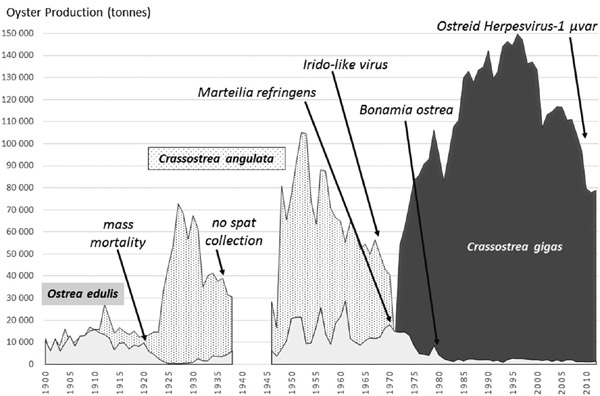

Figure 3.1 Major crises affecting the shellfish farming industry in France

Source: C. Lupo (Ifremer) and V. Le Bihan (LEMNA) with data from Ifremer (Buestel et al. 2009)

Several critical episodes of mass mortality depleted entirely the oyster stocks in France within the past century (Figure 3.1). Harvested since the antique Roman period, the natural beds of flat native oysters (Ostrea edulis) faced a first collapse because of overfishing in the mid-nineteenth century. The fishery was replaced by a more intensive farming activity from that period until a sudden second collapse put an end to the culture of O. edulis in the early 1920s. A more robust species (O. angulata, also called the Portuguese oyster) had been accidentally introduced after a shipwreck in 1868 and colonized the Atlantic French coast. From 11,700 tons of O. angulata produced in 1925, the domestic production rapidly reached 67,500 tons in 1930 (Le Bihan 2015). This industry grew for decades until a third depletion caused by a viral epizooty of the Iridovirus type occurred in the late 1960s and killed the remaining cultivated stocks. Farmers responded by importing a new resistant species (Crassostrea gigas) in the early 1970s. The most recent epizooty striking the oyster stocks concerns this latter species.

The outbreaks started during summer 2008 and were still ongoing in 2016. The environmental stress introduced by the presence of an Ostreid herpes virus mutant species (OsHV1-μVar; Maurer et al. 1986, EFSA 2010) has resulted in higher vulnerability of oyster larvae and juveniles of cupped oysters (C. gigas), bad quality of shell and new epizooty episodes (Vezina and Hoegh-Guldberg 2008), suffering tremendous mortality rates (up to 80 percent–100 percent) for juveniles. Mass mortality of living organisms is generally defined by a loss exceeding 30 percent of stocks (Soletchnik et al. 2007). This sudden mortality may have been caused by recent changes in environmental conditions, like higher temperatures (with a critical threshold of 16°C), but no clear causal relationship has been found so far on a scientific basis, suggesting that several concurrent stressors have caused this recurrent outbreak every summer (Pernet et al. 2011).

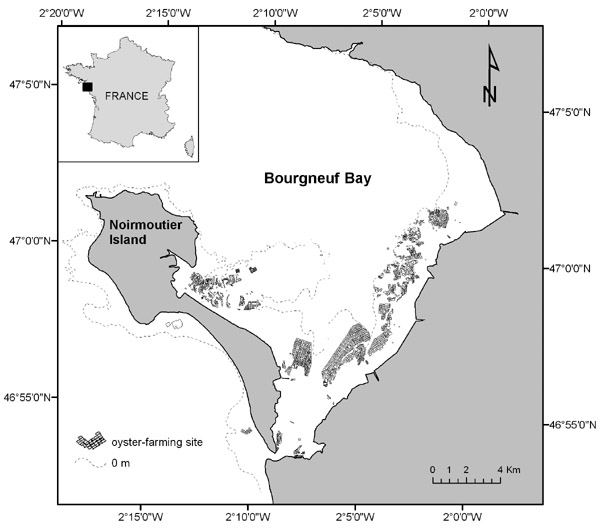

Although the phenomenon hits all oyster basins in France, we chose to focus our analysis on one single case study: the Bay of Bourgneuf. This case study is particularly relevant for the I-ADApT project because an extreme shock (pathogen possibly linked with climate change) is jeopardizing the future of a coastal industry, therefore pressing the oyster farmers and the collective management institutions to respond firmly in order to avoid bankruptcy. This issue is not specific to France because the same pathogen has been found with similar consequences in Australia and New Zealand (Castinel et al. 2015). The Bay of Bourgneuf is located in the Bay of Biscaye, off the Atlantic French coast. Oyster farming represents the major activity in the bay, with an average production (prior to the issue) of approximately 10,000 tons (representing 13 percent of domestic output) produced by 283 farms. The total area of the bay is 340 km², including 100 km² of tidal flat foreshore where oysters are mostly settled (exposed at ebb tides; Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.1 Major crises affecting the shellfish farming industry in France

Source: C. Lupo (Ifremer) and V. Le Bihan (LEMNA) with data from Ifremer (Buestel et al. 2009)

The Bay of Bourgneuf is a semi-open, funnel-shaped bay (mouth is 12 km in the north and 0.8 km in the south for a 30-km-long bay), with muddy and sandy flat grounds and a few patches of rocky grounds. In the north of the bay, the average depth is 10 meters, separated by three channels of 13 to 17 m deep. In the south, where oyster farming is concentrated, a vast sandy and muddy foreshore, uniformly flat, has a depth of 1 to 3 meters unveiled at ebb tide.

Figure 3.2 Map of the Bay of Bourgneuf on the French Atlantic coast

Source: Laurent Barillé, Researcher in marine ecology at the University of Nantes, personal communication

The bay is subject to a semi-diurnal tidal cycle (magnitude between 1.5 and 6 meters and tidal coefficients of 100). Several small rivers flow in, but they are insufficient to influence the ecology of the bay, unlike the estuary of the Loire River in the north which brings sediments to the bay (0.5 m yr–1). The natural well of groundwater provides a constant temperature of 13°C, favorable for primary production of high-quality microalgae for oysters. The water temperature varies between 4°C in winter and 23°C in summer. A rise of +1.5°C was observed in the Bay of Biscaye (0–50 m depth) between 1970 and 2000 (Koutsikopoulos et al. 1998).

The water in the bay is one of the most turbid in Europe because of the Loire sediments: 154 mg l–1 in the north and 34 mg l–1 in the south around the oyster tables (Haure and Baud 1995). Such turbidity is not the best environment for oyster growth because of less photosynthesis, but this is partially compensated for by the rich groundwater and the high salinity (28–36 g/l). Concerning the pH, it varies seasonally between 7.9 and 8.5, without any change observed recently in the bay (Barille-Boyer et al. 1997), but a 0.1 decrease of pH has been observed in the larger Bay of Biscaye throughout the twentieth century, and a 0.5 decrease is predicted for the twenty-first century (Pörtner 2008, Caldeira and Wickett 2005), with potentially dramatic consequences for shelled animals.

All in all, the natural productivity of the bay is considered low compared to other oyster basins in France. The ratio between the Bay of Bourgneuf and the most productive basin (northern Brittany) is around 1 to 1.4 (Le Bihan and Pardo 2012).

On the social side, the Bay of Bourgneuf is surrounded by several small towns, separated by a few kilometers, and with a few thousand people living in each of them. Overall, some 90,000 inhabitants (up to 320,000 in the summer) live around the bay, with the island of Noirmoutier bordering the western side. On a broader scale in France, oyster farming represents a current production of 104,000 mt per year (87 percent of the European production), with 36,600 leaseholds managed by 2,500 farm units employing 10,000 workers. Oyster farming is a family business. Men usually work at sea (on the oyster shelves) while women work on shore (triage, sales). In 2014 the tonnage of sold oysters represented 58 mt per business unit with a standard deviation of 77 mt, showing the small firm size and the great dispersion amongst them.

Most of the cultured oysters are sold in the domestic market. Imports and exports amount to only 6 percent and 8 percent of total production, respectively (Le Bihan et al. 2013). Oysters reaching the commercial size are sorted by size and sold directly by producers to end consumers in stall markets (80 percent), while the remaining sales go to other buyers (restaurants, retailing chains). There is an important business to business (B-to-B) activity, with some oystermen being hatchers, whereas others are only growers, brokers or shippers. Firms are increasingly vertically integrated towards more upstream integration since the beginning of the mass mortality issue, with farmers wishing to hold more leased grounds where they can collect natural spat to complement the inputs from hatcheries.

The number of active oystermen is declining, and the average age of farmers is increasing because of tough working conditions. The whole industry is getting more concentrated: the number of business units was reduced by 13 percent between 2001 and 2006, and the number of lease holders had fallen even more dramatically within the past decades: -35 percent between 1991 and 2004 (Le Bihan et al. 2008).

The area hosts a few other activities, such as tourism and agriculture mainly. Agriculture is not affected by the oyster mortality issue, but rather can be considered another source of trouble for oyster growers because of the pesticides flowing to the watershed and affecting the quality of the coastal sea. Conflicts between oystermen and land farmers are quite frequent and usually debated within the local water committees.

The governing system is vertically organized first at the national level, through the National Shellfish Council (Conseil National de la Conchyliculture or CNC), and then at the regional level through the shellfish regional committees in charge of implementing the national laws and rules (Comités Régionaux de la Conchyliculture or CRC). CNC and CRCs thus represent the interests of the industry before the state, the European Commission or consumers. The number of CRCs is between 5 and 10, with this number being set by law but subject to changes when several management regions are merged to follow the dynamics of the industry. Each committee includes 50 to 60 members. They are self-funded by member fees, along with additional support from public subsidies. Shellfish producers and workers represent 60 percent of the membership, with the other members coming from the hatcheries, processing and retailing sectors. Members are nominated through bylaws for four years by the state (Préfet de Région), which sets the number and distribution of seats. Besides the CRC, the Regional Committee of Fisheries and Aquaculture (COREPEM) is a private organization funded by its own members‘ fees and in charge of representing both fishers and farmers. Although the chairman of the CRC is also a member of the COREPEM board, COREPEM is not a key structure of the shellfish industry: no specific working group is dedicated to shellfish matters, and most management decisions concerning the latter are made within the CRC and CNC.

The prevailing rule governing the activity concerns the access to intertidal grounds and to marine areas. Lease holds are granted by the state to growers on the public maritime domain and as such cannot theoretically be traded. The grounds are usually leased for a period of several decades (e.g. 30 years) and transmitted from generation to generation. However, because some of the grounds bear higher productivity than others, the best growing areas are subject to grey market transactions between lease holders (Bailly 1994).

The management rules in the Bay of Bourgneuf area are decided within the community of producers. The nominated chairman and the management committee have full power over the working rules in force at the basin scale and bed levels. In the specific case of the Bay of Bourgneuf, the chairman of the CRC is one of the largest oystermen in the area and he owns grounds outside the area in foreign and other French basins. Also a member of COREPEM and CNC, he enjoys great influence over any decision adopted by the regional committee.

In spite of this concentrated power, one may consider that the management rules are not really binding for the industry. Stock externalities between the shellfish beds should command that every producer is limited in the allowed amount of inputs (spat) put on the shelves (Le Bihan 2015). This common limitation of effort is decided by law at the regional level through the structural management scheme (schéma des structures). The number of oyster meshbags allowed for breeding is capped by the CRC management committee. Quotas are fixed by species (mussels, oysters, cockles, etc.), by technique (bottom, shelf, subtidal), number of shelves/ha and number of meshbags per shelf through the management scheme. No other rule has been enforced to determine the number of seeds per meshbag, leaving farmers free to decide their own amount of spat introduced in the system. Resource management is thus weak in the Bay of Bourgneuf, with the oystermen acting rather individually.

When the issue of mass mortality first occurred in summer 2008, the natural system responded by higher mortality rates striking 80 percent to 100 percent of young oysters. Because of transfers from basin to basin, pathogens have been broadly disseminated at the national and international levels (virus OsHV-1 μ-var, and bacteria Vibrio splendidus and V. aestuarianus). These outbreaks usually take place during the spring and summer seasons, starting in April or May, with a gradient of mortality spreading from south to north along the French coast. The causes of these sudden viral outbreaks are not clearly understood, but scientists hypothesize a link with a water temperature threshold of 16°C and beyond (Pernet et al. 2011).

On the governing side, the fear of bankruptcy for the industry led the government to release a large amount of financial support. Between 2008 and 2010, nearly 135 M€ were granted by the state to the industry (Le Bihan 2015). It represents a substantial amount for an industry generating a sales value of 562 M€ in 2011. Under the pressure of the industry, the state also invested a lot in research and development (R&D) to look for the root causes of the phenomena. Among the set of actions, the government and CNC enforced restrictions on the transfer of oysters between basins to contain the dissemination of the viruses, under the European regulation 175/2010 setting the conditions to organize quarantine areas and transfers of animals (e.g. transfers allowed only if the host destination is also contaminated).

In 2010 the CNC, Ifremer (Research marine institute), the CRCs and five private hatcheries launched a replenishment program to select resistant species (R-oysters), preferably from triploid seeds. This program was extended in 2011 and 2012. Out of the 26 analyzed samples, results show that some significant survival rates had been obtained for 2nR and 3nR, particularly beyond the 16°C threshold (survival rate of 2nR oysters 62 percent vs. 88 percent for non-R diploid oysters) (Chavanne et al. 2013). The CRC also decided to cap the number of bags per shelf during that crisis period. Though interesting, the effects of these measures were limited in space and tonnage, and oystermen had to develop individually their own strategy of self-protection and self-insurance.

Far more effective and fast was the response from the industry itself (social system). A paramount number of spat collectors were immersed by oyster farmers, who also leased new grounds in the areas of larvae emissions. A consequence was the fivefold increase of leasehold exchange prices between 2008 and 2013. Farmers have also been granted access fishing rights for wild oysters by the public authorities in order to replenish the beds in culture. In addition, growers have purchased more seeds from hatcheries, particularly of the triploid type. They have also experimented with new culture strategies, such as positioning shelves at different depth levels of the intertidal zone, testing for different densities of seeds in the meshbags, developing offshore techniques, importing species from Brazil (hatchery oysters) or Japan (natural oysters), etc. It is not easy to report all the responses adopted by the industry because very little information has been made public due to competition between farmers.

In summary, the major response has certainly been a large increase in the number of cultured juveniles and a massive investment in hatchery triploid spat to anticipate the high mortality rates and keep a constant level of output. Such a strategy is criticized by many scientists who consider that over-investment and higher density increase the risk of dissemination (Pernet et al. 2011), but these measures have possibly saved many business units from bankruptcy.

The issue of oyster mass mortality cannot be considered as being addressed because the mortality rates were still very high (50 percent–80 percent) eight years after the first outbreak. Production levels have logically decreased, but the French oyster industry is still alive and quite prosperous. How can such a paradox be explained?

The natural system is hard to describe in the present case study, as well as the concept of resilience defined by Holling (1973) or Pimm (1984). Resilience is understood as the capability of ecosystems to absorb as rapidly as possible unexpected shocks and still persist, both in structure and function (same biodiversity, trophic relationships, habitats, etc.). In the present case study, the ecosystem results from the massive introduction in the early twentieth century of an alien oyster species (C. angulata and C. gigas) for aquaculture purposes. Far away from the pristine state of the natural ecosystem, the anthropic influence shows a certain degree of control over the ecosystem services in the case of aquaculture. Resilience here means that the same level of resource extraction (shellfish production) should have recovered after the shock.

The domestic oyster production in France fell to 75 percent of the pre-crisis level before stabilizing around 80,000 mt since 2011. The causes of the mass mortality summer episodes remain unknown, although several hypotheses of virus outbreaks (Ostreid herpes virus and Vibrio spp.) are high on the research agenda. No resistant species has been successfully discovered so far. On a more positive side, it can be reported that the ecosystem is less loaded in cultured oysters, resulting in greater quantity of feed for trophic competitors.

At the national level, the number of shellfish farming units has slightly decreased between 2008 and 2011 (-1.1 percent), but the number of jobs has remained fairly stable. In order to cope with the high mortalities, the strategic choices have been different in other French oyster basins, according to the characteristics of oyster farms and those of the ecosystem. In the region where the Bay of Bourgneuf is located, the number of full-time equivalent jobs has even increased by 4 percent because of the development of spat collection to respond to the mortality shocks (DPMA/BSPA, aquaculture survey).

A major consequence of the response has been an intensification of sales of intermediate goods between farmers: +10 percent of tonnage between 2008 and 2011, but +94 percent in sales value because of the sharp increase in prices, whereas the sales to final consumers dropped by 25 percent from 105,000 mt to 79,000 mt between 2008 and 2011 (Le Bihan 2015). If the number of domestic firms selling to end consumers had fallen by 13 percent between 2008 and 2011 (from 1,957 to 1,695), the number of B-to-B units had increased by 17 percent (from 1,083 to 1,265), compensating partially for the loss. Managers observe that the crisis may have led the industry to get rid of the most vulnerable firms (oldest and smallest business units, people involved part-time in this industry) in a sort of selection process for the survival of the fittest. Those companies that resisted the shock seem to show better economic performance.

The price increase (+76 percent for intermediate goods and +51 percent for final goods) was an unexpected outcome of the mass mortality crisis. The market responded quite instantaneously to the shock by a demand shift and higher willingness by end consumers to pay for what they considered to be a threatened species. Oysters are particularly appreciated by households during Christmas periods, explaining why consumers are less sensitive to price changes. But this rising price was partially offset by the twofold augmentation of input costs between 2010 and 2011 due to the increasing supply of hatchery and natural spat. This type of cost now represents 25 percent to 30 percent of total production costs, which have increased by 18 percent to 76 percent in the regions between 2007 and 2011 (Le Bihan 2015). Based on a survey carried out in 2014 of 264 farms, 57 percent reported stable or a higher level of profits after the crisis, whereas 32 percent saw a decline of their sales value, and 8 percent faced higher debt levels (Ibid.).

With strong state support and the EC regulation 175/2010, the main existing institutions (CNC and CRCs) framing the management rules have been quite fast in responding to the mass mortality issue striking the French oyster industry. Substantial public financial aid was given to farmers in the first years of the crisis, which allowed most of them to survive. More research has been funded to identify the causes and search for resistant species through various public and private organizations such as Ifremer, universities and private hatcheries. If the short-term response can be considered timely and effective, it cannot be so in the long run because the actual causes of the disease have not been discovered and the problem remains unsolved.

If a quarantine scheme and some measures of transfer restrictions have been decided, very little has been done to improve the management system towards less density and fewer animals left in the water. A single measure of meshbag number limitation was taken, and the quantity of oyster seeds put in the bags by shellfish growers has sharply increased. In spite of the structural management scheme implemented at the oyster bed level, the current institutions have very little power to impose restrictions onto the input and output levels. Information is barely transmitted to the committee, and top-down measures often fail to be fully enforced. The lack of knowledge regarding the quantity of cultured stocks is considered as hindering the implementation of a risk hedging or risk management policy for the shellfish industry (Le Bihan 2015).

The mass mortality of cupped oysters faced by the French industry since 2008 is neither new nor specific to this country (Soletchnik et al. 2007). What is peculiar in the present case study is the repetition of severe mortality crises throughout the history of shellfish farming in France. Different causes (cold winters, overinvestment, virus, bacteria, etc.) have resulted in a sudden collapse of the cultured stocks every few decades. The response has often been the same: to introduce a new resistant (and often alien) species instead of the previous one. A focus on a French sub-region (the Bay of Bourgneuf) and the use of the I-ADApT framework allow for a more accurate look at the variety of responses invented by local stakeholders to the pathogen issue affecting a man-made shellfish ecosystem.

Against all scientific recommendations claiming for a limitation of animal transfers between basins and a reduction of spat as inputs of the shellfish production, the oyster growers have intensified their production by collecting more oyster spat, leasing more grounds for natural spat collection and purchasing more triploid oyster seeds from hatcheries. By doing so, they increased substantially the transfers of animals between areas, hence the risk of pathogen dissemination.

Eight years after the first disease outbreak, the core issue remains unsolved (mortality rates reaching very high values above 50 percent), but the shellfish industry has escaped general bankruptcy by adapting the investment in inputs to the current mortality rates. The market response following the 25 percent decline of production has been a large price increase (50 percent–75 percent) standing still at this high level several years after. Small business units left the market, particularly those selling to end consumers, but others have been created at the stage of seeds and juvenile production. Whatever the level of vertical integration, most of the surviving firms have even increased their profit levels since the mortality crisis.

It can therefore be concluded that the social system proved to be resilient, even though the resilience of the natural system is harder to define when it comes to such artificial and anthropized marine systems (Guillotreau et al. 2017). In that respect, some lessons can be drawn from this case study in which the origin of the crisis remains uncertain; meanwhile the industry can nonetheless cope with the disease in the short-term, thanks to the rapid adaptability of farmers, the firmness of markets and state aid during the first months of the issue. However, the response given by the industry cannot be considered satisfactory in the long run according to many observers, even though no one can deny a certain short-term success in social and economic terms. Monoculture systems in shallow coastal waters are more vulnerable than other systems to global warming and ocean acidification, which can be considered ‘slow variables’ (Walker and Salt 2006). The lack of redundancies and diversity in the system, known as key factors of natural resilience, may jeopardize it in the long run.

This research was supported by the French ANR-Agrobiosphere program GIGASSAT. We are grateful to our colleagues Fabrice Pernet (Ifremer) and Pierre Gernez (University of Nantes), the two coordinators of this inter-disciplinary project dealing with oyster mass mortality issues in France.

Bailly, D. (1994). Economie des ressources naturelles communes: la gestion des bassins conchylicoles. PhD Thesis, University of Rennes 1.

Buestel, D., Ropert, M., Prou, J. and Goulletquer, P. (2009). History, status, and future of Oyster culture in France. Journal of Shellfish Research 28(4): 813–820.

Caldeira, K. and Wickett, M.E. (2005). Ocean model predictions of chemistry changes from carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere and ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research Oceans (1978–2012) 110(C9): 2156–2202.

Castinel, A., Dhand, N., Fletcher, L., Rubio, A., Taylor, M. and Whittington, R. (2015). OSHV-1 mortalities in Pacific Oysters in Australia and New Zealand: The farmer‘s story. Cawhthron Institute, Report No. 2567, New Zealand, 69 p.

Chavanne, H., Maurouard, E., Yonneau, C., Heroin, D., Ledu, C., Degremont, L. and Benabdelmouna, A. (2013). Plan de sauvegarde 2011: synthèse des résultats 2011–2012. Technical Report, Ifremer.

Guillotreau, P., Allison, E.H., Bundy, A., Cooley, S.R., Defeo, O., Le Bihan, V., Pardo S., Perry, R.I., Santopietro, G. and Seki, T. (2017). A comparative appraisal of the resilience of marine social-ecological systems to bivalve mass mortalities. Ecology and Society 22(1): 46.

Haure, J. and Baud, J.-P. (1995). Approche de la capacité trophique dans le bassin ostréicole (Baie de Bourgneuf). http://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00000/6441/.

Holling, C.S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4: 1–23.

Koutsikopoulos, C., Beillois, P., Leroy, C. and Taillefer, F. (1998). Temporal trends and spatial structures of the sea surface temperature in the Bay of Biscay. Oceanologica acta 21(2): 335–344.

Le Bihan, V. (2015). Analyse économique du risque en conchyliculture. PhD thesis, University of Nantes.

Le Bihan, V., Pardo, S. and Guillotreau, P. (2013). Risk perceptions and risk management strategies in French Oyster farming. Marine Resource Economics 28: 285–304.

Le Bihan, V. and Pardo, S. (2012). La couverture des risques en aquaculture. Une réflexion sur le cas de la conchyliculture en France. Economie rurale 329: 16–32.

Le Bihan, V., Le Grel, L. and Perraudeau, Y. (2008). Aquaculture. In: P. Guillotreau (Ed.) Mare Economicum: Enjeux et avenir de la France maritime et littorale. Presses Universitaires de Rennes, France, pp. 139–191.

Maurer, D., Comps, M. and His, E. (1986). Caractéristiques des mortalités estivales de l’huître Crassostrea Gigas dans le bassin d’Arcachon. Haliotis 15: 309–317.

Pernet, F., Barret, J., Le Gall, P., Lagarde, F., Fiandrino, A., Huvet, A., Corporeau, C., Boudry, P., Quéré, C., Dégremont, L., Pépin, J.-F., Saulnier, D., Boulet, H. and Keck, H. (2011). Mortalités massives de l’huître creuse: causes et perspectives, Final report on Mortalities affecting C. gigas in the Thau pond, Ifremer RST/LER/LR 11–013, 75 p.

Pimm, S.L. (1984). The complexity and stability of ecosystems. Nature 307(26): 321–326.

Pörtner, H.-O. (2008). Ecosystem effects of ocean acidification in times of ocean warming: A physiologist’s view. Marine Ecology Progress Series 373: 203–217.

Soletchnik, P., Ropert, M., Mazurié, J., Fleury, P.G. and Le Coz, F. (2007). Relationships between oyster mortality patterns and environmental data from monitoring databases along the coasts of France. Aquaculture 271: 384–400.

Vezina, A. and Hoegh-Guldberg, O. (2008). Effects of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems: introduction. Marine Ecology Progress Series 373:199–201.