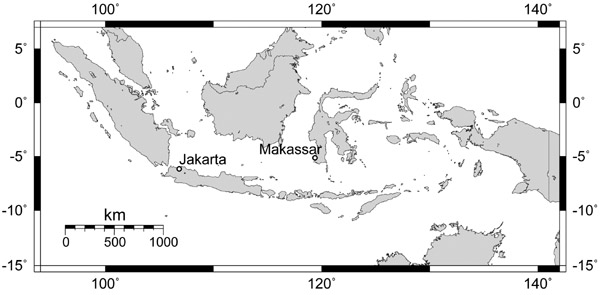

Indonesia is a global marine biodiversity hotspot. Unsustainable use of marine resources pose major threats to the viability of its coastal and marine ecosystems (Burke et al. 2011; Siry 2011). It has been predicted that Indonesia faces the strongest decline in marine fisheries of any nation until 2055, with a potential decrease of over 20 percent (Cheung et al. 2010). Without adequately addressing the continuous degradation of coastal and marine ecosystems, this will have a tremendous impact on the livelihoods of coastal populations. This case study assesses the responses that have been developed to address this issue in the Spermonde Archipelago, South Sulawesi Province (Figures 4.1 and 4.2) and follows the I-ADApT framework, template and methodology as outlined in the introductory chapter of this volume.

The Spermonde Archipelago is home to one of the largest reef fisheries in Indonesia (Pet-Soede and Erdmann 1998). Marine resources are crucial to provide the islands’ households with income (Pet-Soede et al. 2001). Long-term environmental data are difficult to obtain for the area, as there are no dedicated and systematic monitoring programs, but available anecdotal information indicates that degradation has accelerated considerably in the last 30 to 40 years. Today, the fisheries resources are heavily depleted (Ferse et al. 2012; Glaeser and Glaser 2010, 2011; Glaser et al. 2010; Hoeksema 2004), and a growing number of fishermen compete for increasingly scarce marine resources, resulting in continuously degrading marine ecosystems (Deswandi 2012; Bruckner and Borneman 2006). The large and growing number of inhabitants, in combination with low environmental awareness, results in an overuse of marine resources and fresh water lenses, scarcity of available land for construction and farming and pollution. Climate change further exacerbates the situation by adding environmental stressors to the system (Glaser and Glaeser 2014).

Fieldwork included five research excursions of about 10 days each to the Spermonde islands in 2009, 2010, 2012 and 2013, each with over 20 members from natural and social science disciplines. In addition, multiple individual research visits of several weeks to the region were carried out between 2009 and 2013. The methods employed included a survey with fishers and anthropological fieldwork. Key interviews and focus group discussions were conducted with fishers, traders, middlemen, elders and young women and men in Spermonde, Makassar and the city of Pangkajene (Glaser et al. 2015). The research covered 20 of the inhabited Spermonde islands (Figure 4.2).

The Spermonde Archipelago is part of the province of South Sulawesi (Sulawesi Island, also known as Celebes) in Indonesia. It covers an area of approximately 2,500 km2, consisting of about 67 low-lying coral atoll islands; 54 of these islands are inhabited. The islands’ inhabitants are almost exclusively dependent on marine resources for their livelihoods (Ferse et al. 2014).

The shelf area extends up to 60 km from mainland Sulawesi and stretches around 80 km along the west coast of South Sulawesi. It is situated in front of the city of Makassar, home to about 1.8 million people, or almost 3 million in the wider metropolitan area. A few islands have been inhabited for several centuries, but most were settled more recently (Schwerdtner Máñez and Ferse 2010). All islands have seen considerable population growth during the past 50 to 60 years.

The predominant livelihood activity in the area is fishing, using multiple fishing gears and targeting numerous fish species. However, a wide range of species are harvested in an unsustainable and even destructive manner (Hoeksema 2004; Pet-Soede and Erdmann 1998). A number of different species, economically and ecologically important and in some cases endangered, have been severely overharvested, with little signs of recovery. These include groupers, sea cucumbers, turtles, dugongs, sharks and a number of stony corals sold to the international marine aquarium trade. As returns are diminishing and competition and demands for profits increase, there is an inevitable race for ever more efficient fishing technologies. Fishermen are motivated to forage in the waters surrounding islands other than their home islands and to use distant fishing grounds outside the Spermonde Archipelago. Island fishing grounds are not only exploited by the adjacent islanders, but also by outside fishermen (Deswandi 2012). As a result of the links to external markets, the variety of fishing gear the low effectiveness of law enforcement and the widespread perception that marine resources are inexhaustible, there is little concern as to overfishing. Burgeoning rules on access to marine waters, previously considered free for all (Glaser et al. 2010), indicate a closing of the marine frontier, mimicking developments in the forests of the Sulawesi highlands (Li 2014).

The shelf area is confined to the east by the Sulawesi mainland and to the west by deep waters of the Makassar Strait. There is a strong current system along the western boundary of the shelf (Indonesian through-flow), characterized by complex current patterns within the archipelago (predominantly from northwest to southeast). Three major rivers discharge into the marine system on the eastern side, with a strong gradient in nutrients (and to some extent in salinity) across the shelf from east to west (Cleary et al. 2005). Two main seasons with associated changes in wind patterns (rainy northwest monsoon and dry southeast monsoon) define the annual climate pattern (Cleary and Renema 2007). According to local informants, however, seasonality has changed. Research revealed that local inhabitants perceive that rain and storms have become less frequent but more intense and seasons have become less predictable.

Habitats consist of coral reefs, seagrass beds and a few mangroves along the shore. Most mangroves have been destroyed for shrimp and fish ponds, and reefs have been declining in coral cover as well as associated fauna over the past four decades. Although many reefs closer to shore are degraded, some along the shelf edge in the west are in better condition. Directly along the mainland shore, reefs are highly eutrophied, with strong sedimentation and low visibility and reduced diversity. High trophic levels (sharks, groupers, snappers) and larger individuals are very rare, and abundances of most groups (except some planktivorous fishes and some invertebrates) have declined (Hoeksema 2004). Dugongs (sea cows) and turtles are rare. Corallivorous crown-of-thorn starfish are becoming more and more common (Plass-Johnson et al. 2015). Many reefs areas have been reduced to rubble due to blast fishing and bleaching (Edinger et al. 1998). As in most coral reefs, high light levels, constant temperatures and salinity and low nutrient levels are the prerequisite for healthy and diverse coral communities and associated fauna.

The archipelago is home to some 45,000 people (official data vary) and an estimated 6,500 fishing households. Fifty years ago, only a few islands were inhabited by just a few people. Migration from the mainland has increased population density ever since. People even settled on islands without drinking water (Schwerdtner Máñez et al. 2012). Most of the islands are densely inhabited, with densities of up to 750 people/ha (Schwerdtner Máñez et al. 2012). Two main ethnicities live on the islands: Buginese and Makassarese from South Sulawesi, in addition to descendants of the Bajau/Bajo (sea gypsies) and other minor ethnicities.

Regarding economic aspects, the ‘system’ extends over a very large geographic area. The dominant source of income is fishery based, including fish processing and trading (Ferse et al. 2012), for 80 percent of the population. Approximately 70 percent of the fishery operations are small scale (one to four people per boat), with the remainder of the fishers engaged in medium-scale operations (purse seining and mobile lift-net fishery with 10 to 20 people per boat). Within a wide variety of target species and fishery types (Breitkopf 2014), the Spermonde fishery includes the live reef fish and sea cucumber fisheries with traders and exporters in Makassar and customers in Singapore and China (Ferrol-Schulte et al. 2014; Ferse et al. 2014), all of which influence the social system of Spermonde. This holds true for ornamental fish and markets in North America, Europe and East Asia. The type of fishing varies from island to island. People target certain species and adopt the gear accordingly. Some fishers earn a very good living, whereas others are rather poor. Fishers employing destructive methods (e.g. blast fishing) belong to the most affluent fishers on the islands. Poor fishers are those with only small boats and a small net or hook.

The vast majority of fishers are organized in a patron–client system (locally called punggawa-sawi). Although there are also independent fishermen, patron–client relationships play an important role in the Spermonde fishery and other parts of Indonesia (Ferrol-Schulte et al. 2014). Such patron–client systems have long been a customary feature in traditional Indonesia and wider Southeast Asia, not only in the fishery industry (Acciaioli 2000; Li 2014; Merlijn 1989). Fishing patrons provide credit in times of hardship, access to markets, fishing gear and licenses (Yusran 2002; Nurdin and Grydehøj 2014). In particular, those punggawas involved in trading fish caught by destructive practices and those involved in the live reef food fish trade are usually powerful and wealthy patrons. They use their contacts with law enforcement agencies to provide insurance against prosecution in case illegal fishing gear is used or protected species are caught (Chozin 2008; Radjawali 2011). However, these Punggawas may also go bankrupt, be heavily indebted or change back to fishing or other occupations. Sawis (linked fishers) are bound to Punggawas (patrons) by social contracts, usually involving debt. They fish around local or adjacent island waters unless ordered elsewhere by the captains of their boats (Punggawa laut). Punggawas who are traders do not influence the choice of fishing location (Breitkopf 2014). Punggawas sell the catch on Makassar or Surabaya (Java) markets or via middlemen internationally to Hong Kong and elsewhere. Sawis sell their catch to their supporting Punggawa (usually at a lower price if indebted to these traders), whereas independent fishermen can choose between different traders.

Fishing and trading are almost exclusively a male activity. Men are also engaged in auxiliary fishery activities, such as boat building, carpentry and net fixing (Figures 4.3 and 4.4). In all our research, we came across only one female patron. However, household finances are usually the women’s domain. Fishermen’s wives sell fish to traders or intermediaries and sometimes at the local markets. Usually, the fish fetching the best prices is sold, whereas the lesser-quality ones are used for household consumption. Women are involved in seaweed cultivation, sell goods in local (partly mobile) shops for consumption (food, sweets, drinks, textiles, etc.) and work in small-scale enterprises such as a crab factory on one of the islands. The wives of traders often do the accounting. The fishers’ wives cook food for their husbands and the fishing crew. Outside the fishery, artisans, petty traders, religious leaders and some people with government jobs (nurse, teacher, etc.) can be found on the islands.

Alternative livelihood options are generally scarce. Very few extensive aquaculture activities can be found: shrimp ponds and seaweed, grouper, sea cucumber husbandry and coral culture (Glaser et al. 2015). In most cases, these activities are rather ephemeral; very few operations have been sustained for more than a few years. Post-harvesting activities are varied: drying fish, crabs, seaweeds and sea cucumbers; boiling and smoking sea cucumbers; boiling and peeling crabs; and packing live ornamental organisms and live grouper. The high dependence on diminishing marine resources, the restricted space available on the islands, the population growth, the weak educational system and the lack of alternative livelihood approaches prevent economic development at a local level.

Figure 4.3 Construction of wooden jolloros. Carpenters display precise workmanship.

Photo: Bernhard Glaeser

Figure 4.4 Trader Musbari estimates the value of fisherman Sikki’s sea cucumber catch

Photo: Bernhard Glaeser; all names changed by the authors

The social system looks quite resistant to change at first sight. Fishermen stick to their habits and methods. Nevertheless, changes are happening if opportune. Fishers are quick to adopt new fishing techniques or target species or enter new social contracts if opportunities arise, shifting to new patrons for novel species and markets (Ferse et al. 2014). Fishers are often in a permanent search for opportunities to improve their income. Baits are changed or adapted every few years as fish are perceived to ‘learn’ (Breitkopf 2014). On a larger scale, shifts in target species are visible as distinct peaks in the volume of caught species are followed by declines. In recent years, the time between increase and decline of new fisheries has shortened (Ferse et al. 2014).

In the course of decentralization following the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998, more authority was relegated from the central to provincial and district government agencies (Satria and Matsuda 2004; Wever et al. 2012). As a result, the Spermonde Archipelago governance system is based on regulations that are nested across multiple levels, from the international level (such as the Coral Triangle Initiative, a joint initiative by six Southeast Asian and Melanesian countries to improve coral reef and marine management and coastal livelihoods) to the local level. This situation has led to difficulties in coordination between different levels of government and sometimes overlapping and unclear responsibilities for managing marine resources (Ferrol-Schulte et al. 2015; Satria and Matsuda 2004; Wever et al. 2012).

The Spermonde Archipelago is part of the province of South Sulawesi and encompasses five districts: Makassar, Maros, Takalar, Pangkajene dan Kepulauan (Pangkep) and Barru. At the district level, the administrative responsibility for the archipelago’s waters and islands only rests with two districts: Makassar and Pangkep (Figure 4.2). Administrative sub-levels below the regency/district are the sub-districts (kecamatan) followed by the village level (desa = rural village and kelurahan = urban village/neighborhood). Each village is again organized in additional smaller administrative units (Beard 2002). The social organization is highly hierarchical, which has also strong effects on the governance structure (Gorris 2015).

Diverse government departments nested across multiple administrative levels have particular responsibilities for managing marine resources in the Spermonde Archipelago. Key informant interviews showed that the general government responsibilities in marine resource management include strategic planning, implementation of programs, monitoring and enforcement of marine resource–related regulations. The strategic planning creates a mix of bottom-up and top-down approaches. The standard procedure for program planning takes one year and involves different government and non-government stakeholders. The result of the annual planning cycle is a program plan for government-funded projects for one year. The standard procedure to be followed in these projects consists of three phases: implementation, monitoring and evaluation.

On the national level, the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries was newly established (first as a department in 2000 and later as a ministry in 2010). Prior to this, marine resources management was under the Ministry of Forestry (Dudley and Ghofar 2006). In addition, the Balai Konservasi Sumber Daya Alam (BKSDA) is a national government department responsible for marine species protection and the in situ conservation of endangered marine species, including their habitat. It has offices in different parts of Indonesia, including Makassar.

On both the province and district levels, the regional planning and development agency BAPPEDA (Badan Perencana Pembangunan Daerah) is responsible for marine spatial planning. The fisheries department Dinas Kelautan dan Perikanaan (DKP), however, is the main government department concerned with marine resource management. DKP is organized on the province level as well as on the district level. But the district DKPs are not line agencies of the provincial DKP. Rather, they have to coordinate but operate independently. The general objective of DKP is, first, the enhancement of fisheries production and, second, the conservation of the marine ecosystems. Additional agencies responsible for trade, credit, development, etc., also influence marine resource management.

The laws and guidelines that regulate and affect the use of marine resources in Spermonde range from national law to village regulations (Peraturan Desa). The responsibility of enforcing fishery and marine conservation–related laws such as the prohibition of destructive fishing (i.e. bomb and poison fishing) in Spermonde Archipelago primarily rests with the DKP Seksi Pengawasan, the DKP enforcement unit. In addition, both the police and military have sections which are also involved in the enforcement of maritime law. Going beyond the enforcement of laws pertaining to the management of marine resources, their responsibility also includes the enforcement of laws prohibiting the use of destructive fishing gear. Polair or Polairut (the water police), which is responsible for the Spermonde area, has its main headquarters in the city of Makassar. To increase effectiveness of enforcement, a Polairut section was also created in Pangkep in 2010. Similarly, the Angkatan Laut (navy) assists in the enforcement of fisheries and conservation laws. Yet neither the police nor the military has been subject to the decentralization legislation for multiple reasons, including political stability in the aftermath of the shift of the political system in Indonesia, but instead they have remained under national authority (Hadiz 2010; Jansen 2008). Hence, neither the province nor the district governments have strong influence on the performance of the military or the police.

Responses have been developed by a variety of government and societal actors in the Spermonde Archipelago to adapt to the changing circumstances and mitigate the degradation of natural resources.

Different types of responses have been made by the government at multiple levels. Quotas for, or a total ban of, fishing of protected species; the ban of destructive fishing gear; and the implementation of marine protected areas (MPAs), from community-based MPAs to a marine national park, are the main instruments of marine resource management in the area. The following details the main responses made by the government.

Pangkep district is one of the sites of the Coral Reef Rehabilitation and Management Program (COREMAP), a multi-year program funded by the World Bank and Asian Development Bank and currently Indonesia’s largest program supporting formal community-based MPA development. The objective of the COREMAP program is to protect, rehabilitate and sustainably manage the use of coral reefs and related marine resources. A community-based MPA program is implemented, explicitly aiming to involve local communities in MPA management. In order to meet regional-scale conservation objectives, no-take MPAs are declared for and by each village in the Pangkep district. These small-scale, local-level MPAs are implemented in 15 villages on 42 islands (Glaser et al. 2015). As an outcome of the second phase of COREMAP, a Kawasan Konservasi Laut Daerah (KKLD, i.e. a multi-use MPA under Indonesian law) was created in the area. The locally administered MPAs created by village law called Perdes (Peraturan Desa), which are no-take-zones, mark the core zones of the KKLD. The management plan for the KKLD has recently been accomplished, and the implementation of the management scheme is ready to start. However, a management board has not yet been defined in relation to the task. In Pangkep district, local officials who are part of the organizational structure created and funded by COREMAP assist in marine management of community-based MPAs. Several of the MPAs were gazette, with socio-economic and ecological monitoring reports being published. Credit funds were created and distributed, although they usually only reached a certain circle of people (Glaser et al. 2015).

In Makassar district, one major focus of DKP relates to the establishment of POKWASMAS (kelompok pengawas masyarakat, or community guard groups) in the islands. The POKWASMAS consist of about 10 islanders each. Their main responsibility is to assist the government in implementing projects and the protection of the waters around their island from destructive fishing. In most islands, they are not really active and lack funds to carry out their tasks.

In both districts, fishing gear has been distributed and micro-finance institutions established by the government. Capacity-building activities are carried out by DKP, local universities or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) as a long-term activity. The capacity-building events (such as workshops) not only target the village organization, but also aim to improve knowledge of government staff.

The level of education is low, and only few options to engage in alternative livelihood strategies exist. Local populations have thus adopted a number of coping strategies to mitigate the impacts of overuse of natural resources jeopardizing their livelihoods.

A strategy to mitigate the continuous impacts of destructive fishing by local populations includes the development of locally enforced rules surrounding some inhabited islands in all of Spermonde (Deswandi 2012). These rules are mainly based on informal agreements about fishing gear and restrictions. They usually prohibit the use of destructive methods in the waters that are considered to ‘belong’ to a certain island (Deswandi 2012). These regulations thus apply to a small sea territory surrounding various islands, creating a polycentric structure of informal conservation measures (Glaser et al. 2010). Their formation as well as their enforcement highly depend on local leaders (Deswandi 2012; Idrus 2009), which creates a dependency on these individuals for the successful implementation of such area-based measures.

To cope with sudden disturbance events such as storms or loss of gear, the patron–client system provides fishers with an alternative type of social security, allowing them to overcome times of hardship (Ferse et al. 2014). De facto, fishing patrons and village heads also play important roles in governing fishing activities (Ferse et al. 2012).

Another coping strategy to deal with coastal erosion included the construction of wave breakers (Figure 4.5). With the aid of government funds, they addressed the perceived coastal erosion. However, coral stone was used as a construction material to build the wave breakers, which is a highly unsustainable resource use practice. The irony was that, because using building materials from the mainland is extremely expensive, there were not enough funds to bring in materials from the outside. The coral cays of Spermonde are naturally highly dynamic systems, with complex patterns of erosion and accretion (de Klerk 1983). The local perception of a link between reef degradation and coastal erosion may thus be a result of the increased exposure to programs such as COREMAP that underline climate change as a cause of reef degradation, coupled with increased density of settlement on the islands that reduces the scope for reacting to dynamic coastlines by relocating to different parts of the island (Polewali and Karanrang).

Local populations are to some extent supported by NGOs and COREMAP in the development or implementation of coral farming, mariculture and cultivation of seaweeds to provide alternative livelihood options. These actors introduced credits to empower self-employment in mobile restaurants or shops (drinks, snacks, tools).

Photo: Bernhard Glaeser

Human impact in the Spermonde Archipelago by far exceeds the capacity of reefs to recover. Exploited stocks show little to no signs of recovery. A wholesale phase shift into a macroalgae-dominated state has not yet happened, indicating that some key ecological functions (e.g. herbivory) are still sustained (Plass-Johnson et al. 2015), but marine resource depletion probably increases in speed.

Human development and sustainable resource management are often considered an objective of governance (Li 2007). With regard to the government’s responsibility for addressing the problem of overuse, that certainly is true, although with mixed outcomes. Two rather conflicting objectives are found in the governance system. One major aim is to ensure the conservation of marine ecosystems, whereas another major objective is to increase fishery production. This Janus face becomes particularly apparent when taking a look at the DKP. Whereas their objective is both marine conservation and fisheries production, they clearly focus on increasing productivity in order to meet the production goals, particularly in Makassar district, at the expense of long-term sustainability. Enhancing fisheries production may have short-term positive effects on the social system which outweigh the negative impact on the natural system, but it undermines any conservation effort.

Government responses are generally obstructed by flaws in the implementation of laws and management projects. Implementation of management measures particularly suffers from conflicting interests of government departments, power struggle and corruption (Idrus 2009; Wever et al. 2012). Environmental awareness and alternative livelihood trainings were set up, but do not meet the needs of islanders. Available information and decisions taken are frequently not made transparent, which results in limited outreach (Glaser et al. 2010). Collusion and mismanagement of funds have tremendous negative impacts on the effectiveness of the government responses (Idrus 2009). Neither police nor the navy, both with fundamental responsibilities in the governance system, have been subject to decentralization, and lower-level governments have only limited means to improve the performance of these agencies. Participatory programs also do not appear to be very effective, as local communities remain barely integrated in management efforts. The COREMAP program consists of an elaborate structure for local implementation, including provisions for community participation. Yet research suggests that the process of selection of personnel and the zoning and implementation of MPAs were not particularly participatory (Glaser et al. 2010).

Local populations have generated two main responses to deal with the changing circumstances: the long-established intricate patron–client links and informal rules on resource use (Ferrol-Schulte et al. 2014; Ferse et al. 2014). Conservation considerations seem to play only minor roles, however, and local economic interests prevail. We find a high dependence of the island population on increasingly scarce marine resources, which has led to a race for the ‘last fish’ (Deswandi 2012). The enforcement of local rules for marine territories may thus be perceived rather as to aim at protecting the local economy against outsiders instead of conservation objectives (Polunin 1984). Nevertheless, this response also benefits the marine environment. Although the existing patron–client system can be seen as an alternative type of social security against sudden shocks, the capacity to cope with more extensive stressors such as the complete loss of ecosystem services (fisheries resources, protection from erosion) appears limited (Ferse et al. 2014). The self-perpetuating patron–client system entrenches existing power inequalities and locks in undesirable trajectories, undermining the long-term sustainability of the system (Ferse et al. 2014; Grydehøj and Nurdin 2015). There are no signs that patrons would forego benefits in favor of environmental sustainability.

In conclusion, the patron–client links may serve as a short-term coping strategy (Ferse et al. 2014), and informal rules may be seen as a long-term mitigation measure. Both seem to be locally more feasible solutions than the rather ineffective official government responses. Local elites, to some extent in tandem with outsiders, are mainly responsible for the development of these local responses which have to be backed by the local populations. Responses with higher impact are a collaborative effort driven by local actors with the active involvement of local elites.

Mirroring national-level marine policy, governmental programs in Spermonde fail to adequately address exposure of island communities to marine resource degradation, while also remaining inadequate in their attempts to increase adaptive capacity (e.g. by provision of credit or alternative livelihoods). Shortcomings in marine management and ineffective law enforcement make it unlikely for the official governance system to respond adequately to the degradation of marine ecosystems. Island community responses seem to be better positioned to address the issue. The patron–client links and informal rules on marine resource use developed at a local level are more effective responses compared to the rather ineffective measures taken by the government. Judging from the current poor state of the system, it appears unlikely that there will be an adequate governance response in due time. The I-ADApT template can be considered a useful tool to harmonize case studies and to improve their comparability so that conclusions can be drawn for management decisions in different world regions, responding to different coastal and marine problems and issues.

This research was supported by the German Ministry for Research and Education (BMBF) in the frame of the SPICE project, grant numbers 03F0474A and 03F0643A. We would like to extend our deep gratitude to the communities of the various islands in Spermonde that patiently tolerated years of scientific inquiry and were generous hosts throughout. Many thanks also to our colleagues and student participants of the various research visits. This work developed from shared experiences and lengthy discussions over several years, and we are grateful for this interaction, in particular, with Marion Glaser, Muhammad Neil, Kathleen Schwerdtner-Máñez, Sainab Husain and Hafez Assad.

Acciaioli, G. (2000). Kinship and debt. The social organization of Bugis migration and fish marketing at Lake Lindu, Central Sulawesi. Bijdr Taal Land Volkenkd 156: 588–617.

Beard, V.A. (2002). Covert planning for social transformation in Indonesia. J Plan Educ Res 22: 15–25. doi: 10.1177/0739456X0202200102

Bruckner, A.W. and Borneman, E.H. (2006). Developing a sustainable harvest regime for Indonesia’s stony coral fishery with application to other coral exporting countries. In: Y. Suzuki, T. Nakamori, M. Hidaka et al. (Eds.) 10th International coral reef symposium, Okinawa, Japan, June 28–July 2, 2004. Japanese Coral Reef Society, Tokyo, Japan, pp. 1692–1697.

Burke, L., Reytar, K., Spalding, M. and Perry, A. (2011). Reefs at risk revisited. World Resource Institute (WRI), Washington.

Cheung, W.W.L., Lam, V.W.Y., Sarmiento, J.L., Kearney, K., Watson, R.E.G., Zeller, D. and Pauly, D. (2010). Large-scale redistribution of maximum fisheries catch potential in the global ocean under climate change. Global Change Biol 16: 24–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365–2486.2009.01995.x

Chozin, M. (2008). Illegal but common: Life of blast fishermen in the spermonde archipelago, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. MA Thesis, Ohio University.

Cleary, D.F.R. and Renema, W. (2007). Relating species traits of foraminifera to environmental variables in the Spermonde Archipelago, Indonesia. Marine Ecology-Progress Series 334: 73–82. doi: 10.3354/meps334073

Cleary, D.F.R., Becking, L.E., de Voogd, N.J., Renema, W., de Beer, M., van Soest, R.W.M. and Hoeksema, B.W. (2005). Variation in the diversity and composition of benthic taxa as a function of distance offshore, depth and exposure in the Spermonde Archipelago, Indonesia. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science 65: 557–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2005.06.025

De Klerk, L.G. (1983). Zeespiegels, riffen en kustvlakten in Zuidwest Sulawesi, Indonesie: een morfogenetisch – bodemkundige studie. PhD thesis, Utrecht University, p. 174.

Deswandi, R. (2012). Understanding institutional dynamics: The emergence, persistence, and change of institutions in capture fisheries in Makassar, Spermonde Archipelago, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. PhD Thesis, University of Bremen.

Dudley, R.G. and Ghofar, A. (2006). Technical Report no 2: Marine and coastal resource management. Marine and Fisheries Sector Strategy Study (ADB TA 4551 – INO), Prepared by Uniconsult International Limited (UCIL), Jakarta. 74p +app.

Edinger, E.N., Jompa, J., Limmon, G.V., Widjatmoko, W. and Risk, M.J. (1998). Reef degradation and coral biodiversity in Indonesia: Effects of land-based pollution, destructive fishing practices and changes over time. Marine Pollution Bulletin 36(8): 617–630. doi: 10.1016/S0025–326X(98)00047–2

Ferrol-Schulte, D., Ferse, S.C.A. and Glaser, M. (2014). Patron-client relationships, livelihoods and natural resource management in tropical coastal communities. Ocean and Coastal Management 100: 63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.07.016

Ferrol-Schulte, D., Gorris, P., Baitoningsih, W., Adhuri, D.S. and Ferse, S.C.A. (2015). Coastal livelihood vulnerability to marine resource degradation: A review of the Indonesian national coastal and marine policy framework. Marine Policy 52: 163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.09.026

Ferse, S.C.A., Knittweis, L., Krause, G., Maddusila, A. and Glaser, M. (2012). Livelihoods of ornamental coral fishermen in South Sulawesi/Indonesia: Implications for management. Coastal Management 40: 525–555. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2012.694801

Ferse, S.C.A., Glaser, M., Neil, M. and Schwerdtner Máñez, K. (2014). To cope or to sustain? Eroding long-term sustainability in an Indonesian coral reef fishery. Regional Environmental Change 14: 2053–2065. doi: 10.1007/s10113-012-0342-1

Glaeser, B. and Glaser, M. (2010). Global change and coastal threats: the Indonesian case. An attempt in multi-level social-ecological research. Human Ecology Review 17: 135–147.

Glaeser, B. and Glaser, M. (2011). People, Fish and Coral Reefs in Indonesia. A contribution to social-ecological research. GAIA 20: 139–141.

Glaser, M., Radjawali, I., Ferse, S.C.A. and Glaeser, B. (2010). ‘Nested’ participation in hierarchical societies? Lessons for social-ecological research and management. International Journal of Society Systems Science 2: 390–414.

Glaser, M. and Glaeser, B. (Eds.) (2014). Linking regional dynamics in coastal and marine social-ecological systems to global sustainability. Regional Environmental Change (REC) 14(6), special issue

Glaser, M., Breckwoldt, A., Deswandi, R., Radjawali, I., Baitoningsih, W. and Ferse, S.C.A. (2015). Of exploited reefs and fishers – a holistic view on participatory coastal and marine management in an Indonesian archipelago. Ocean Coastal Management 116: 193–213.

Gorris, P. (2015). Entangled? Linking governance systems for regional-scale coral reef management: Analysis of case studies in Brazil and Indonesia. PhD thesis, Jacobs University, Humanities and Social Sciences, Bremen.

Grydehøj, A. and Nurdin, N. (2015). Politics of technology in the informal governance of destructive fishing in Spermonde, Indonesia. GeoJournal 81(2): 281–292. doi: 10.1007/s10708–014–9619-x

Hadiz, V.R. (2010). Localising power in post-authoritarian Indonesia. A Southeast Asia perspective. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Hoeksema, B.W. (2004). Biodiversity and the natural resource management of coral reefs in Southeast Asia. In: L.E. Visser (Ed.) Challenging coasts: Transdisciplinary excursions into integrated coastal zone development. Amsterdam University, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, pp. 49–71.

Idrus, M.R. (2009). Hard habits to break, investigating coastal resource utilisations and management systems in Sulawesi, Indonesia. PhD Thesis, University of Canterbury.

Jansen, D. (2008). Relations among security and law enforcement institutions in Indonesia. Contemporary Southeast Asia 30(3): 429–454. doi: 10.1355/cs30–3d

Li, T.M. (2007). The will to improve. Governmentality, development, and the practice of politics. Duke University Press, Durham and London.

Li, T.M. (2014). Land’s end: Capitalist relations on an indigenous frontier. Duke University Press, Durham and London.

Merlijn, A.G. (1989). The role of middlemen in small-scale fisheries: a case study of Sarawak, Malaysia. Development and Change 20: 683–700.

Nurdin, N. and Grydehøj, A. (2014). Informal governance through patron – client relationships and destructive fishing in Spermonde Archipelago, Indonesia. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 3: 54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.imic.2014.11.003

Pet-Soede, L. and Erdmann, M. V. (1998). Blast Fishing in Southwest Sulawesi, Indonesia. Naga ICLARM Q 21: 4–9.

Pet-Soede, L., Van Densen, W.L.T., Hiddink, J.G., Kuyl, S. and Machiels, M.A.M. (2001). Can fishermen allocate their fishing effort in space and time on the basis of their catch rates? An example from Spermonde Archipelago, SW Sulawesi, Indonesia. Fisheries Management and Ecology 8(1): 15–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365–2400. 2001.00215.x

Plass-Johnson, J.G., Ferse, S.C.A., Jompa, J., Wild, C. and Teichberg, M. (2015). Maintenance of fish herbivory as key ecological function in a heavily degraded coral reef system. Limnology and Oceanography 60(4): 1382–1391 (published online). doi: 10.1002/lno.10105

Polunin, N.V.C. (1984). Do traditional Marine “Reserves” conserve? A view of Indonesian and New Guinean evidence. Senri Ethnology Studies 17: 267–283.

Radjawali, I. (2011). Social networks and the live reef food fish trade: Examining sustainability. Journal of Indonesian Social Sciences and Humanities 4: 65–100. doi: URN:NBN:NL:UI:10–1–101744

Satria, A. and Matsuda, Y. (2004). Decentralization of fisheries management in Indonesia. Marine Policy 28(5): 437–450. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2003.11.001

Schwerdtner Máñez, K. and Ferse, S.C.A. (2010). The history of Makassan Trepang fishing and trade. PLoS ONE 5, e11346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011346

Schwerdtner Máñez, K., Husain, S., Ferse, S.C.A. and Mánez Costa, M. (2012). Water scarcity in the Spermonde Archipelago/Sulawesi, Indonesia: Past, present and future. Environmental Science and Policy 23: 74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.07.004

Siry, H.Y. (2011). In search of appropriate approaches to coastal zone management in Indonesia. Ocean and Coastal Management 54(6): 469–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.03.009

Wever, L., Glaser, M., Gorris, P. and Ferrol-Schulte, D. (2012). Decentralization and participation in integrated coastal management: Policy lessons from Brazil and Indonesia. Ocean and Coastal Management 66: 63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.05.001

Yusran, M. (2002). Ponggawa-sawi relationship in co-management: An interdisciplinary analysis of coastal resource management in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. PhD Thesis, Dalhousie University.