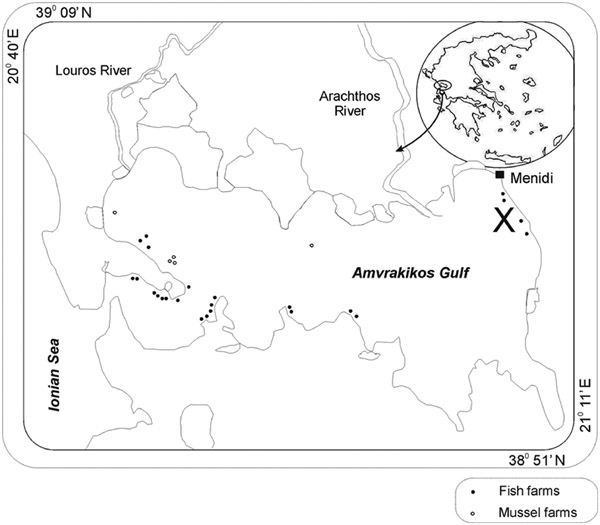

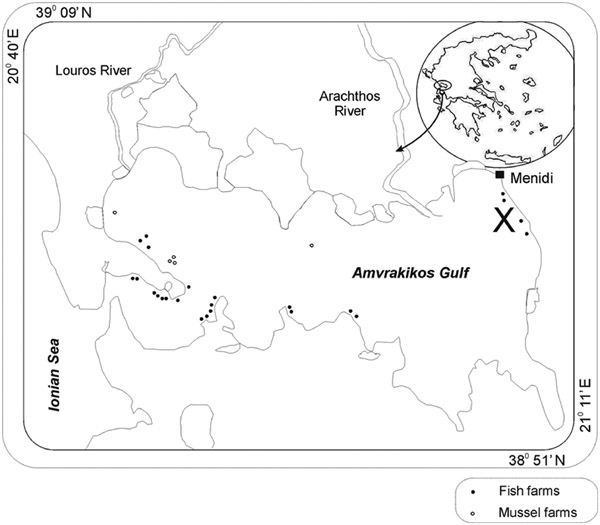

Figure 6.1 The location of Amvrakikos Gulf and the distribution of marine fish farms

The massive fish kill occurred close to the municipality of Menidi (marked with an ‘X’ in the northeast sector of the gulf).

Amvrakikos Gulf is a natural, protected (Natura 2000 Network), semi-enclosed, fjord-like embayment characterized as a ‘national park’ in Greek legislation (Figure 6.1). It is 35 km long and 15 km wide. Along the coastline of the gulf is a complex of 18 lagoons covering approximately 20 percent of the surface, most of which are natural reserves for wild life. Traditionally, these sites are used by local communities for activities such as capture-based aquaculture of diadromous fish.

Fresh water inputs to the gulf come from the Louros River (mean annual flow 19 m3/s; length 80 km; drainage basin 785 km²) and the Arachthos River (mean annual flow 69 m3/s; length 140 km; drainage basin 1894 km²) which also has a hydroelectric dam (since 1981) at the northern part of the gulf. Both systems contribute to the high nutrient loading of the gulf due to the effluent of urban areas, intensive agriculture and livestock production. As a consequence the gulf is a high productivity system, with high phytoplankton and zooplankton abundances (Panagiotidis et al. 1994). Several pollutants, including heavy metals, sewage and pesticides, are directed into the gulf through the drainage canals and rivers (Kotti et al. 2005; Ferentinos et al. 2010).

Water from the Ionian Sea enters the gulf through a shallow elongated strait, providing partial but inadequate replacement of the internal seawater masses of the gulf. It is estimated to take a year for complete renewal of the Amvrakikos waters (Papayannis et al. 1986).

The fjord-like hydrological regime, combined with the eutrophic profile of Amvrakikos, causes strong vertical stratification of the oxygen all year round. Despite the surface waters being well mixed to a depth of 10 m, below that the dissolved oxygen decreases to less than 2 mg/L at 20 to 25 m and almost disappears below 35 m. Dysoxic or anoxic seawater masses have expanded to more than half of the surface area of the gulf (Ferentinos et al. 2010).

Upwelling of anoxic bottom water masses to the surface can occur during periods of strong winds, causing massive fish mortalities. The massive mortality incident described in this study occurred in the area of Menidi City, northeast Amvrakikos Gulf (Figure 6.1). About 42 percent of the municipal district population (2,032 individuals in 2011) are residents of the city, which is located on the shoreline.

Figure 6.1 The location of Amvrakikos Gulf and the distribution of marine fish farms

The massive fish kill occurred close to the municipality of Menidi (marked with an ‘X’ in the northeast sector of the gulf).

The six lagoons in the northern part of the gulf act as a natural reserve and host extensive capture-based fish culture systems. The lagoons are natural habitats for euryaline species such as grey mullets, European silver eels, grass gobies and sea bream. Other species that occur in limited harvesting quantities include soles, sea bass and caramote prawn (Katselis et al. 2013). The main bivalves of commercial interest are Mediterranean mussels (Rodrigues et al. 2015), and populations with potential exploitation interest include scallop and several other benthic species. Amvrakikos is also the main habitat of protected aquatic animals such as the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncates) (Bearzi et al. 2008a) and the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta).

Approximately 80,000 people live around the Amvrakikos Gulf. Most of them (62.5 percent) inhabit two big cities, Arta and Preveza, located on the northern part of the gulf. The rest of the population is spread among communities of 2,000 to 10,000 people (five municipalities) and fewer than 2,000 people (30 municipalities and communities). The major livelihood activities are agriculture and livestock production, which is mostly distributed in the northern part of the gulf. The land is fertile and well irrigated with the main products being corn, clover and cotton. Intensive cultivation of orange, citrus, olives and kiwis also occurs, whereas garden products are farmed indoors in expanded greenhouses. Amvrakikos Gulf is characterized as a fisheries-dependent area according to Tzanatos et al. (2005) with an average annual catch by Greek fishermen of approximately 530 tons (Spyratos 2008). Fresh water and diadromous species such as trout, eels and mullets are produced intensively or semi-intensively in land-based facilities in the north but production capacity is limited. Farming of marine species (mainly sea bass and sea bream) has developed during the last three decades, and an effort to cultivate mussels is under way (Theodorou et al. 2015). With such rich resources, supplementary small and medium food packing and processing industries have developed to add value to the local products. These include slaughterhouses, meat processing factories, dairy/cheese, orange and lemon juice factories and fish packing and processing facilities. Despite the area being highly productive, with rich natural resources, the gross product (GP) per person (Arta inhabitants) is significantly lower than the national average. Traditional extensive activities such as lagoon fisheries, grazing and marginal agriculture are not economically viable but continue to be operated for supplementary income (Spyratos 2008).

The major stakeholders directly affected by the massive fish kill phenomenon included fish farmers, fishermen and the tourist industry. Among the fish farming industry, there are 22 grow-out cage farms of Mediterranean marine species, mainly sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) and sea bream (Sparus aurata), around the gulf (Karras et al. 2010) with a total annual production of 7,000 tons (Gonzalvo et al. 2015). Most (18 farms) are concentrated in the southwest and northwest part of the gulf (Vonitsa to Preveza). Four more cage farms are located in the northeastern part of the gulf (Menidi area) where the mass mortality occurred (Figure 6.1).

The fishermen’s society of Amvrakikos Gulf, a medium dependence fishing area in Greece (Tzanatos et al. 2005), includes 360 active small-scale fishing boats. The average age of the fishermen (2008) was about 54 years, with a basic educational level (70 percent elementary and 30 percent secondary school graduates). Fishing also provides employment to 30 percent of fishermen’s wives, of the rest, 15 percent work in agriculture and 30 percent in housekeeping. Since the 1990s, traditional coastal fishing communities around the gulf have been reduced due to declining catches and decreased incomes from fishing (Tzanatos et al. 2005). The continuity of fishing between generations has been reduced from 60 percent between first and second generations to 39 percent between the second and the third. Alternative and supplementary incomes now come from seasonal employment in agriculture and construction industries (Gonzalvo et al. 2015). Only 5 percent of the professional fishing boats are now located in Menidi (NE Amvrakikos), the area most affected by the fish kill, while the rest are shared between Preveza (NW) (80 percent) and Amphilochia (SE) (15 percent) (Spyratos 2008).

The tourism industry and leisure activities are restricted to 5 percent of the land area of the Amvrakikos coastal region, with most of the remaining space used for traditional primary sectors such as agriculture, fisheries and aquaculture. The natural park and environmental protected area of Amvrakikos has the potential for development of ecotourism activities. This strategy could be further improved if it supplements the tourism that is well developed in the outer part of the gulf and the Ionian Sea by providing alternative opportunities to visitors to the wider area (Gonzalvo et al. 2015). The tourism stakeholders affected by the mass fish kills were several small family-owned businesses such as residences (one hotel and seven apartments/rooms to let) and catering businesses (about a dozen taverns and cafeterias) in the city of Menidi.

The governance of Amvrakikos Gulf is shared between three prefectures belonging to two different regions: i) the prefecture of Aitoloacarnania (western Greece), which covers the southern and the major eastern part of the gulf, and ii) Preveza and Arta prefectures (region of Epirus) mainly in the northern part. Decisions about coastal activities in each region are made through the relevant authorities. For the management of the entire Amvrakikos Gulf, a consortium (Corporation for South Epirus and Amvrakikos Gulf development: ET.AN.AM AE) has been formed between the neighboring counties.

The coastal location in which the mass mortality event occurred (Menidi) is under the direction of the prefecture of Aitoloacarnania close to the border with the prefecture of Arta. As a result, the responsible authority to manage the crisis was the Fisheries Directorate of Aitoloacarnania Prefecture. Supplementary support was offered by the Veterinary Directorate of the prefecture, the port/coast guard authority of Menidi and the Management Agency of Amvrakikos Gulf.

Legislation regarding the Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) of the region has recently been developed by updating, upgrading or replacing the existing rules which referred to the coastal users, that is, the Common Spatial Planning Framework for Aquaculture (Theodorou et al. 2015). Because Amvrakikos is a Ramsar Convention Site (https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/61) belonging to the EU Natura 2000 network, several additional European rules (mainly provisions of Directive 92/43/CEE “Habitats”) are in effect to protect local endangered species such as sea turtles (a priority species of community importance listed in annexes II and IV of the Habitats Directive), dolphins (Council Decision 1999/337/EC) and Dalmatian pelicans (registered in Annex I of the Directive 2009/147/EC for the Conservation of Wild Birds).

Reports of massive fish mortalities due to upwelling events have been increasing in the literature. Despite the same outcome (fish kills), the causes may differ from site to site and are often related to local environmental conditions (McInnes and Quigg 2010; Stauffer et al. 2012). La and Cooke (2011) demonstrated that in most of the cases studied in the United States, the causes may originate from anthropogenic activities, in association with physical phenomena. These events are commonly detected in lakes, lagoon ecosystems or semi-enclosed embayments, usually with significant fresh water inputs and restricted water circulation and water renewal.

This study analyzes a similar case in Amvrakikos Gulf, north central Greece, emphasizing the management of the outcomes rather than the possible causal agents, which have been described in detail in other studies (Ferentinos et al. 2010). Several previous short-term local mass mortality events were ‘underestimated signals’ and required limited management actions. Our effort is focused on the crisis management of a large volume of dead fish and the socio-economic governance of the consequences. The practical manipulations of such unexpected and large disasters, including crisis communications to the public during the event, are also discussed.

Fish reared in cages along the coast of Menidi (northeastern Amvrakikos) started losing their normal swimming activity during the night of February 17, 2008, and then began dying and accumulating at the bottom of the cage nets. Sea bass and sea bream were predominantly the fish killed, shared between 68 cages in three neighboring farm sites. Four cages had a biomass between 35 and 40 tons of fish each, and 14 cages had more than 20 tons of fish per cage. The total collapsed farmed fish population, remaining stagnant on the bottom of each cage net 13 to 19 m deep, had to be harvested as soon as possible to avoid pollution from the decay of this huge biomass. An estimation based on the stocking densities of each cage gives a total loss of approximately 950 tons of fish. It was reported (18/2/08) that the sea temperature was unusually high (up to 16°C) for the end of the winter with a sharp decrease of oxygen saturation from 40 percent at 2 m down to a complete absence below 10 m. Histopathological analysis of fish samples showed the lack of any causal pathological agent. It was clear that the fish kill occurred due to an upward movement of the anoxic bottom water masses to the surface (Dimitriou et al. 2011). A week after the initial event the dead fish from the bottom of the cages rose upward to the surface of the cages, starting the decomposition of the biomass.

The problems of managing the outcomes of the fish kill concerned the large volume of the submerged (13–19 m) dead biomass and the inadequacy of the existing equipment (vessels, cranes, etc.) to remove the dead fish. During extensive meetings on 19/2/08 between the three affected fish farm owners, the scientific staff of the relevant fisheries, veterinary services, public health and environment directories and the vice-prefect responsible for crisis management under the civil protection authorities, it was decided to engage a specialized company for marine pollution management which had equipment for this purpose. However, the closest company (based in the port of Patras) equipped with the relevant technology (airlifts) had limited available capacity (up to 200 tons within a two-week period). In order to be insured for a bigger capacity, the company requested that service be provided by another company farther away, in Piraeus. Two vessels were engaged, one with the lifting equipment, and the second a ferry boat to transfer the dead biomass. The harvesting capacity ranged up to 100 tons/day (working 14 hours per day). This increased the cost of this operation to 350,000 euros. Identifying public funding of this operation was the next urgent step. The proposed solution was communicated to the Regional Direction (western Greece) and the Athens-based General Secretariat of Civil Protection (Ministry of Citizen Protection), the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Rural Development and Food.

The next question was where to put the dead biomass. The initial proposal to release the harvested biomass in the open Ionian Sea was unsuitable because it would spread pollution. Public resistance by the coastal communities made finding suitable local coastal public areas with access by boats difficult. The local sewage plant was unsuitable due to lack of specification for this purpose. An alternative solution was proposed based on a fish kill event ten years previously, in which the dead fish were buried in private grounds. The request to land owners to provide this service was met with a positive response. In addition, the area had to develop a quick dock with a 30- to 50-m dock (ramba) road in order for the ferry boat to be discharged directly onto the private field. This infrastructure was quickly prepared by the prefecture, including the necessary excavations. Inner surfaces were covered by plastic to prevent leakage of the dead biomass, and excess lime was spread to reduce pollution as much as possible.

Cage and net manufacturing specifications were not designed for these heavy weights and were sensitive to breakage at any time during the operation. The special anti-pollution vessel with the lifting equipment (dredge pump for mud and sand and solids) and the ferry boat suitable to carry away the dead cargo started operating on 24/2/08 and finished on 8/3/2008. Initial underwater efforts by laterally pumping the fish from the side of the cages were unsuccessful. Placing the lifter within the cage made pumping the dead biomass more efficient. In addition, a hand-made dredge (1 m2) manipulated by the crane of the vessels was used to harvest the dead biomass at the surface. When the biomass had been reduced by 50 percent efforts to remove the rest by removing the cage net were only partially successful, as the net materials were not adequate for such heavy loads. For this purpose, new stronger cage nets were passed underneath the existing ones, but again some of them crashed or were destroyed by these heavy loads. Lime was spread on the surfaces of the ferry boat to reduce the strong odors, but with limited success. In addition, sand was spread on the ferry boat to prevent leakage of liquids into the sea. The operation was carried out under calm weather. The outcome might have been completely different if there had been stormy weather.

During the mass mortality event, because the dead fish biomass was extracted from the sea cages within a week, the environmental impact of the organic loading from the leaked body fluids remained low and was limited to the vicinity of the farms.

The Arachthos River plays a critical role in the water dynamics of the gulf. Before the construction of the hydropower dam in 1981, frequent floods would induce deep water mixing. The frequency and quantity of the fresh water floods are now controlled and redirected based on the power needs (Panagopoulos 2008). The dam reduced the velocity of the river and minimized the potential for sedimentation at the estuaries. The fresh water entering the gulf also reduces the density of the upper water layers, which reduces vertical mixing. As a consequence, this eliminates the ‘flushing effect’ of the river on the deep waters of Amvrakikos Gulf (Spyratos 2008), thereby promoting the expansion of the dysoxic or anoxic water masses.

The official identification of the causes of this crisis by the fisheries and veterinary prefecture authorities was debated not only by the local communities, but also by the Public Environmental Agency. As the problem was visible only in the farm cages, coastal communities, environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the media suggested that fish farmers were responsible for this disaster. It was suggested that the problem might have come from diseases spread around the cages as an outcome of overstocking of fish in the farms – a common practice at that time in Greek mariculture. Furthermore, there were discussions in the media about disease transmission to wild populations as well as directly to humans. This caused fear among the local citizens and among the harvesting business staff. Similar opinions of academic professors and opinion leaders/makers through interviews on national broadcasts and TV channels suggested the problem was pollution rather than lack of oxygen. Public trust in the risk management organizations always is critical during a disaster (Nakayachi 2015). The view of the relevant Prefectural Fisheries and Veterinary authorities was strongly supported by providing documented measurements of hypoxia caused by upwelling. If disease was the causal agent, mortality would have appeared gradually in the cages, taking more than a day to become apparent. Pollution was not a direct causal factor as the lack of oxygen was clearly demonstrated.

The three cage farms (out of four) located in the Menidi coastal area were totally destroyed by the loss of their livestock capital. Today, they are bankrupt or out of business. The fourth did not have fish in their cages during this event and avoided the disaster. This farm has now established an early warning monitoring system with backup liquid oxygenation equipment on the land base facility for emergency purposes. An estimate of the money lost because of this crisis, assuming the value of the 950 tons as a final product (4 euros/kg) was about 3,800,000 euros (100 percent loss of the livestock capital). In addition to that, 350,000 euros must be added for the removal of the dead biomass.

Furthermore, the event stimulated fear among Greek consumers about the health and safety of farmed fish, which was expressed by a short-term (a few weeks) drop in demand. Dead fish were not directed to the supply chain and consequently the crisis did not have any serious effect on the image of the product. The farmed fish (sea bass/bream) is an export-oriented commodity with limited market dependence for local/regional consumption.

The massive mortality of the farmed fish in Amvrakikos Gulf had a limited effect on the fishermen and was restricted to the area of Menidi, where fishing activity makes a marginal (5 percent) contribution to the total Amvrakikos fisheries. The problems were mainly focused on the trading of the catches during the period of the event as consumers, at least for few weeks, avoided purchasing local seafood.

Fish farming sites are located away from the city, but the odors from 900 tons of dead fish were widely dispersed, making unsuitable short visits to taverns and restaurants in Menidi on the weekend. This was a major problem at that time, as a Greek bank holiday was close with many visitors expected. So the tourist industry together with the inhabitants of Menidi put pressure on the prefectural authorities to intensify as much as possible the removal of the dead biomass. Because the event occurred in early spring outside of the peak summer tourism season, limited impacts to the annual turnover of the tourism businesses occurred.

La and Cooke (2011) estimated that about 66.9 percent of the mass fish mortalities in the United States are human induced, whereas only 10 percent are due to natural causes. In Amvrakikos Gulf, fish mortalities occurred due to a natural cause (anoxic layer upwelling) that was potentially induced by a human activity (such as stress from the dam flooding). This is consistent with the conclusions of La and Cooke (2011) that fish kills are often linked with heavy rainfalls that increase runoff into aquatic ecosystems. In addition the coastal spatial misplaning of aquaculture exposed the activity to potential risks that otherwise may not have existed. In unsuitable farm site locations, the caged fish are unable to move away from the hypoxic/anoxic conditions and consequently fish kills occur. Insurance claims for farmed fish losses in the same area, as well as past experience from two previous mass mortality incidents (Τheodorou et al. 2003; Koutsikopoulos et al. 2008), indicated the sensitive risk status of the fish farming sites, but were ignored by the decision makers and the relevant stakeholders. The first incident (1/1992) was restricted to the area of Loutraki (south-central Amvrakikos), but resulted in a complete loss of the livestock and closure of the farm. It was reported to be due to a lack of oxygen and unusual increases in surface temperature (7°C–9°C). The second mass mortality event was an extended fish kill in the central-west gulf, which was responsible for 20 percent of the livestock losses in 11 cage farms (12/1998). Both cases occurred during the winter, after heavy rains and very cold weather. During the second (2002) and the third (2008) incidents (data are lacking for the 1998 case), changes of the flow from the Arachthos River dam were reported, indicating that anoxic upwelling may have been induced by the hydrological stress of the rapid introduction of large quantities of fresh water into the ecosystem. This rapid and strong deep vertical mixing of cold fresh water may have affected the bottom of the seawater column. In the last two cases the seawater temperatures (12°C and 16.5°C before the fish kills) were reduced at the surface (12.5°C and 13°C) but increased at the bottom (17.5°C and 16.5°C), indicating mixing of the fresh and salt water masses. The present case of the 950 tons of farmed fish losses at Menidi is a result of underestimation of the ‘risk signals’ from the past events by the stakeholders. The lack of detailed knowledge of how the ecosystem functions, despite a lot of money having been spent in this direction, makes the public administration decision making ineffective regarding the licensing of the marine farms. As the phenomenon has been repeated, there are no further measures to mitigate possible consequences. Furthermore, there is no risk management plan to minimize the possible effects of the Arachthos dam to the ecosystem. In addition, problems of fragmented legislation with gaps in its application must be harmonized in order to improve stakeholders’ management efficiency. The role of the floods as a causal agent of this phenomenon still remains to be studied, to identify practices that could mitigate possible hazardous results. Fish farms may need to be relocated or equipped with relevant oxygenation technologies for these emergencies. Despite this, the fish farmers’ perception is that even under these circumstances (of a permanent threat of an anoxic upwelling) they wish to remain in the same cage sites because the environmental conditions are favorable for the growth of premium quality fish. So they prefer to invest in oxygenation technology as a risk-mitigating action, even if it is an extra overhead cost.

The anthropogenic activities that could induce anoxic upwelling must be identified and studied further in order to provide regional mitigation management plans for each gulf or lagoon ecosystem. The spatial planning of development activities (i.e. aquaculture, power dams) in these areas have to take into account these issues prior to approving the licensing of the projects. In Amvrakikos Gulf, the Arachthos River dam management must become ecosystem oriented rather than meeting only the power demands. Flooding from dams is a key factor causing vertical mixing of gulf waters. The fish kill crisis communication can be effective when data are available regarding the causal agents and decision makers’ positions are understandable and strongly supported. Finally, the technical limitations to remove dead fish have to be taken into account proactively for future crisis management plans. However, harmonization/modernization of the existing legislation and compatibility of practical risk-mitigating actions with the legal implementation are recommended for the development of efficient risk management policies.

Albanis, T.A., Danis, T.G. and Hela, D.G. (1995). Transportation of pesticides in estuaries of Louros and Arachthos rivers (Amvrakikos Gulf, N.W. Greece). Science of the Total Environment 171: 85–93.

Bearzi, G., Agazzi, S., Bonizzoni, S., Costa, M. and Azzellino, A. (2008a). Dolphins in a bottle: Abundance, residency patterns and conservation of bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus in the semi-closed eutrophic Amvrakikos Gulf, Greece. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 18: 130–146.

Dimitriou, E., Parpoura, A.C., Liourdi, M., Milios, C. and Koutsikopoulos, C. (2011). Facts and reactions about the massive farmed – fish mortality in Amvrakikos Gulf, Greece. Proceedings of the 14th Hellenic Ichthyology Congress 14: 363–366.

Ferentinos, G., Papatheodorou, G., Geraga, M., Iatrou, M., Fakiris, E., Christodoulou, D., Dimitriou, E. and Koutsikopoulos, C. (2010). Fjord water circulation patterns and dysoxic/ anoxic conditions in a Mediterranean semi-enclosed embayment in the Amvrakikos Gulf, Greece. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 88: 473–481.

Gonzalvo, J., Giovos, I. and Moutopoulos, D.K. (2015). Fishermen’s perception on the sustainability of small-scale fisheries and dolphin – fisheries interactions in two increasingly fragile coastal ecosystems in western Greece. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 25: 91–106.

Karras, P., Koukou, K., Ramfos, A. and Katselis, G. (2010). Spatial distribution and technical characteristics of west and central Greece marine aquaculture farms. In: Proceedings of the 14th Pan-Hellenic Conference of Ichthyogists, pp. 209–212.

Katselis, G.N., Moutopoulos, D.K., Dimitriou, E.N. and Koutsikopoulos, C. (2013). Long-term changes of fisheries landings in enclosed gulf lagoons (Amvrakikos Gulf, W Greece): Influences of fishing and other human impacts. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 131: 31–40.

Kotti, M.E., Vlessidis, A.G., Thanasoulias, N.C. and Evmiridis, N.P. (2005). Assessment of river water quality in Northwestern Greece. Water Resources Management 19: 77–94.

Koutsikopoulos, C., Ferentinos, G., Papatheodorou, G., Geraga, M., Christodoulou, D., Fakiris, H., Iatrou, M., Spala, K., Moutopoulos, D.K., Dimitriou, N., Katselis, G. and Roussi, A. (2008). Fishing Activity in Amvrakikos Gulf: Current Situation and Perspectives. Final Report. Ministry of Rural Development and Food of Greece, Direction of Fisheries, p. 157 (in Greek).

La, V.T. and Cooke, S.J. (2011). Advancing the science and practice of fish kill investigations. Reviews in Fisheries Science 19: 21−33.

McInnes, A.S. and Quigg, A. (2010). Near-annual fish kills in small embayments: Casual vs. causal factors. Journal of Coastal Research 26: 957−966.

Nakayachi, K. (2015). Examining public trust in risk-managing organizations after a major disaster. Risk Analysis 35(1). doi:10.1111/risa.12243.

Panagiotidis, P., Pancucci, M.A., Balopoulos, E. and Gotsis-Skretas, O. (1994). Plankton distribution patterns in a Mediterranean dilution basin: Amvrakikos Gulf (Ionian sea, Greece). P.S.Z.N. Marine Ecology 15: 93–104.

Papayannis, Th. (Coordinator) and associates. (1986). Amvrakikos Gulf Area. Development of Resources and Environmental Protection. Hellenic Ministry of Physical Planning, Housing and the Environment; Commission of the European Communities, 407 p.

Rodrigues, L.C., van den Bergh, J.C.J.M., Massa, F., Theodorou, J.A., Ziveri, P. and Gazeau, F. (2015). Sensitivity of Mediterranean bivalve mollusc aquaculture to climate change and ocean acidification: Results from a producers’ survey. Journal of Shellfish Research 34: 1161–1176.

Spyratos, V. (2008). Strategic diagnosis of the environmental management of Amvrakikos Wetlands in Greece with emphasis on their water requirements. MSc thesis Water Management, Montpellier, France, p. 181.

Stauffer, B.A., Gellene, A.G., Schnetzer, A., Seubert, E.L., Oberg, C., Sukhatme, G.S. and Caron, D.A. (2012). An oceanographic, meteorological, and biological ‘perfect storm’ yields a massive fish kill. Marine Ecology Progress Series 468: 231–243.

Τheodorou, J., Mastroperos, Μ., Pantouli, P. and Cladas, Υ. (2003). Insurance requirements of mariculture in Epirus. 11th Hellenic Congress of Ichthyology, Preveza, Greece.

Theodorou, J.A., Perdikaris, C. and Filippopoulos, N.G. (2015). Evolution through innovation in aquaculture: The case of the Hellenic mariculture industry (Greece). Journal of Applied Aquaculture 27: 160–181.

Tsotsios, D. (2008). Spat recruitment of the pectinids Chlamys varia and Flexopecten glaber in Mazoma Bay, Amvrakikos Gulf, Greece. MS thesis, University of Thessaly, p. 110.

Tzanatos, E., Dimitriou, E., Katselis, G., Georgiadis, M. and Koutsikopoulos, C. (2005). Composition, temporal dynamics and regional characteristics of small-scale fisheries in Greece. Fisheries Research 73: 147–158.