Jennifer Marie S. Amparo, Dhino B. Geges, Ma. Charisma T. Malenab, Emilia S. Visco, Maria Emilinda T. Mendoza, Carla Edith G. Jimena, Sue Liza C. Saguiguit, Marlo D. Mendoza and Larah O. Ibanez

Background

“They say that there are two sides of development. However, we only experience the negative side of it” (a woman fishpond operator and president of a fishery organization in Meycauayan, Bulacan, Philippines)

Global social-ecological changes are a paradox. Despite the accelerated rate of changes in human activity and innovation, they have also created greater complexity and increased negative impacts from overconsumption and pollution. This paradox is being played out in the world of fisheries. The critical role of fisheries and aquaculture in livelihood provision, food and nutrition security was recognized at the Rio+20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012. The livelihoods of 357 million people directly rely on small-scale fisheries and they employ more than 90 percent of the fish workers in the world’s capture fisheries (World Bank 2008). Fisheries remain a primary source of livelihood and income to approximately 58 million people, with 87 percent of fish and fish farmers residing in Asia. They also contribute to food and nutrition security. In the Philippines, a majority (75 percent) of the national animal protein requirement is provided by fish (Israel and Roque 1999). However, the Philippines’ fishery industry is affected by both internal (overfishing, fish extraction by commercial and small-scale fishers) and external (upstream infrastructure development, changes in water allocation) pressures (Perez et al. 2012). Failure to address these pressures could result in the collapse of this important industry (Perez et al. 2012; Weeratunge et al. 2014).

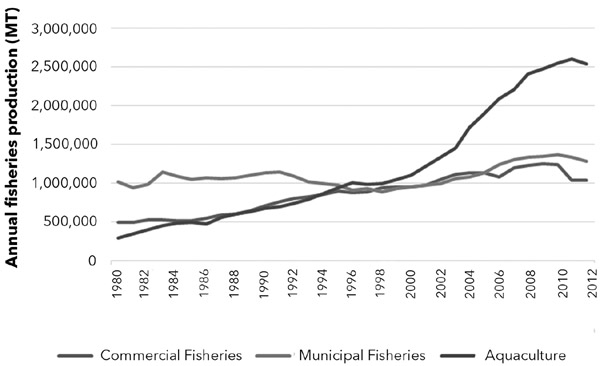

The Philippines is one of the top fish producers in the world, ranking seventh in total fish production in 2012. Due to its archipelagic nature, it is blessed with a long coastline (17,460 kilometers) and a total water area of 220.84 million hectares. Also, the Philippines was an early adopter of co-management in fisheries and has developed national fisheries plans and policies. Total production has increased, with aquaculture accounting for the majority of total fish production in the Philippines from 1996 to 2012 (Figure 11.1). However, the Philippines is also considered to be vulnerable and under threat in terms of food security, fisheries and marine ecosystems (Cabral et al. 2013; Hughes et al. 2012).

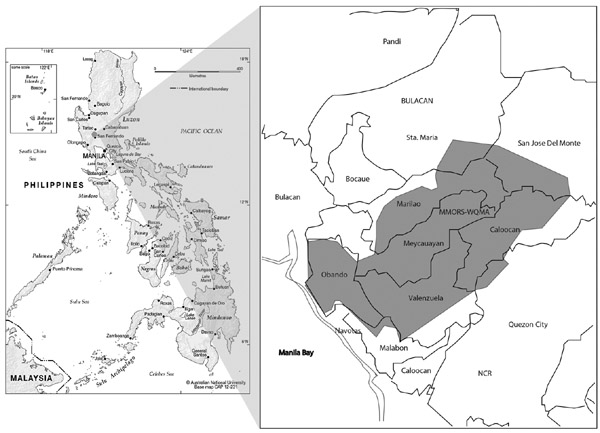

One of the primary aquaculture producers in the Philippines is the province of Bulacan, located north of Manila, with aquaculture accounting for an average of 91 percent of the total fish production of the province from 1980 to 2012 (Bureau of Agricultural Statistics, 1980–2012). As identified by fish farmers from Meycauayan City, Marilao, Obando in Bulacan and Valenzuela City in Manila, the fish and shellfish species grown in these fishponds include tilapia (49 percent), milkfish (31 percent), prawn (12 percent) and shrimp (8 percent) (Malenab et al. 2013). In 2012 it was one of the top three provinces producing tilapia and milkfish. Due to its proximity to the main hub of the Philippines, the flows of development, production and people tend to accelerate in these areas. An important river system in the province is the Marilao-Meycauayan-Obando River System (MMORS). MMORS is a 52-kilometer-long river system with a total size of 130 km2. This river is classified as Class C, meaning the water is beneficial for fishery production and recreational and industrial water supply. Fresh water and brackish water fishes found in the area include tilapia, common carp, lacustrine goby, Indo-Pacific tarpon, different goby species (‘bia’), river mullet and other mullet species. MMORS drains into one of the important marine resources of the country, Manila Bay (Figure 11.2). The major marine fish and shellfish species in Manila Bay and near MMORS include squid, blue crab, anchovies, mullet, threadfin bream, Acetes and Indo-Pacific mackerel.

The MMORS is also home to numerous households, agricultural farms and industries. There are 794 firms along MMORS representing 21 industry types mapped out in 2010 (David 2011). These include tanneries, gold smelting and other manufacturing firms which handle hazardous and regulated substances such as heavy metals. The upstream areas of MMORS like Valenzuela, Meycauayan and Marilao are more urbanized because the industries prefer these areas rather than downstream areas like Obando. The presence of these industries was believed to have contributed to the MMORS’ inclusion as one of the polluted places in the world that poses significant health risks to its surrounding communities (Blacksmith Institute 2007). MMORS’ water quality exceeded its allowable levels of heavy metals and failed in other water quality and biota standards (Blacksmith Institute 2009a). The MMORS’ heavy metal pollution is a result of both active and legacy pollution. Some of the industries that deal with heavy metals like gold smelting and tanneries have been in Meycauayan since the 1950s.

The river pollution heavily affected the aquaculture industry along MMORS. This chapter discusses the effects of heavy metal pollution on fisheries and fish farming along the MMORS. This pollution poses significant risks to the ecosystem, public health and the fishing industry located at the midstream and downstream areas of the MMORS. It also outlines the fish farm practices prior to the main issue, stressors, vulnerabilities and governance and provides an initial evaluation of the responses to the main issue using the I-ADApT decision support tool (Bundy et al. 2016). This chapter is based on 2008 to 2014 research and action projects1 of Blacksmith Institute (renamed Pure Earth in 2014) conducted by researchers and scientists from the University of the Philippines Los Banos, in partnership with the MMO Water Quality Management Area (MMO WQMA) Board (Alfafara et al. 2012).

Traditional fish farming practices and management structure in MMORS

Fish farming occurred in 20 coastal communities of the cities of Valenzuela, Meycauayan, Marilao and Obando. As of 2013, the majority of the fishponds found along MMORS were small (<4 hectares) (Malenab et al. 2013). The type of aquaculture system in the MMORS is traditionally an earth-diked fishpond system. In this type, the first step is to prepare the pond by repairing the pond wall, plowing the pond soil, growing plankton and moss and opening the water gate to a settling pond before water is directed into the grow-out pond. The earth dike enables the fishpond operator to regulate the water quality and quantity in the pond. Stocking of fry and fingerlings follows. The plankton and moss are the initial food for the fish. Commercial feeds are added to hasten fish growth. After two to three months, the fish are ready for harvesting. Depending on the fish catch, 5 kilos or less will be used for household consumption. The rest of the harvest will be sold to the market or to a direct buyer, which is then sold in Bulacan and Metro Manila. Most (80 percent) of the household income in the coastal communities comes from fishing or fish farming.

Small-scale fishers or families living along the MMORS own most of the fish farms. Thus, social power in the area prior to the main issue was characterized as dispersed to a number of small-scale fishers rather than concentrated on limited individuals or investors. The key people in managing a fish farm are the fishpond or landowner, fish farm operator, fish farm caretaker and laborers. The landowner may operate his own fishpond or rent it to a fishpond operator. A fishpond operator pays an annual fee for the use of the fishpond from the landowner. The operator provides the capital, inputs and management of the fish farm and the sale of the harvest. The fishpond operator employs a fish farm caretaker who manages the day-to-day tasks (i.e. feeding the fish, ensuring the security of the farm, dike maintenance, etc.). Caretakers are either paid monthly or/and get a percentage of the proceeds of the harvest. Additional laborers are hired during pond preparation and harvest.

Regulatory agencies such as the Bureau of Fisheries and Agriculture (BFAR) and the agriculture office of the province/municipality provide technical training on good aquaculture practices. However, they focus on small-scale farm operators and provide training upon request. Aquaculture knowledge and practices are commonly passed on to family members who are expected to manage the farm.

The role of women in fisheries

The role of women has been invisible in earlier studies on fisheries (Siason et al. 2001). Women are usually involved in post-harvest activities and marketing fisheries (Center 2010). However, women also play a significant role in actual fisheries and fish farming in MMORS. Women usually catch fish near their coastal communities where they do not need to travel or use a boat to gather fish and shellfish. In an interview with a woman fisher leader in Meycauayan, she shared that their house was built from her earnings from crablets, which she usually gathers just outside her house (personal interview, December 2014). The women also help in feeding the fishes by traversing the earth dike of the pond. They also manage the finances, as women are usually in charge of the sales of the fish.

The MMORS: upstream and downstream stressors and impacts

Fish farming along the river has been practiced for decades. The river and its banks are also home to mangrove forests and a diversity of fish and shellfish. This is evident in the former names of Obando and Meycauayan. Obando, the municipality at the downstream areas of MMORS near Manila Bay, was formerly known as Catanghalan – from the local term ‘tangal’, which is a local species of mangrove. Meycauayan, on the other hand, comes from the word ‘kawayan’, or bamboo.

Due to its proximity to Manila, Bulacan experienced rapid population growth and industrialization over the years. It is also a gateway from the provinces in the north to the national capital region (NCR). Most of the areas, including mangrove forests along the MMO river system, were converted into fish farms and residences. In 1965 the Philippines’ total mangrove area was about 4,500 square kilometers. However, it was reduced to 2,500 square kilometers by 1981; mangrove conversion to fishponds accounts for 60 percent of the decrease. Rice fields along the river were also converted into fishponds due to saline water intrusion.

Industries are commonly located along the upstream river banks, because it is more convenient for wastewater discharge. These areas are attractive for in-migration because they are near to the source of urban employment and livelihoods like fisheries. Population growth ranges from 2.27 percent to 2.73 percent for areas along MMORS and, as of 2007, there were estimated to be 1.28 million residents in the area.

Environmental damage of fresh water and marine waters

The MMORS water quality continues to deteriorate (DENR-EMB 2014). Heavy metals such as chromium, cadmium and lead were found in the Meycauayan and Marilao rivers. The biological oxygen demand (BOD) of the Meycauayan River increased by 213 percent from 2003 to 2005 (Blacksmith Institute 2009b). According to DENR-EMB, the domestic pollution load accounts for 75 percent of the estimated BOD.

Manila Bay has been the focus of regular national clean-up efforts. As early as the 1990s, tons of refuse and industrial waste flowed annually into the bay (Castello et al. 2009). The continued pollution prompted the country’s Supreme Court to issue a continuing mandamus ordering 13 Philippine government agencies to rehabilitate Manila Bay and restore its waters to make them fit for swimming, skin-diving and other forms of recreation. Aside from water pollution, the bay is affected by frequent typhoons and storms which affect water quality, fisheries and fish farm management.

Fisheries plans and projects: from intensification to integration

Since the 1970s, the focus of the government has been on intensification of production to satisfy both domestic and international demands for fish and shellfish. This is evident in the government’s policies and plans on promoting fish production and intensification (Perez et al. 2012). Thus, most of the country’s fisheries projects are aligned with this priority – technology and aquaculture practices development, biological improvement of fish species and distribution of equipment and materials to enhance fish production and fish catch. However, with the adoption of the sustainable development framework in national policies such as the Philippine Agenda 21, fisheries policies have moved towards more integration of livelihood, social equity and habitat conservation and management in fisheries plans and policies.

The Philippines has two major national fisheries policies: Republic Act (RA) 8550 Fisheries Code of the Philippines and the RA 8435 Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act of the Philippines (AFMA). The Fisheries Code “seeks to manage the country’s fishery and aquatic resources in a manner consistent with an integrated coastal area management and to protect the right of fisherfolk, especially of the local communities” (Philippine Judicial Academy 2012). The AFMA promotes the modernization of the agriculture and fisheries sector for improved profitability. Both policies highlight the importance of sustainable development, balancing economic, environmental and social aspects (Israel and Roque 1999).

Natural resource management in the Philippines and MMORS

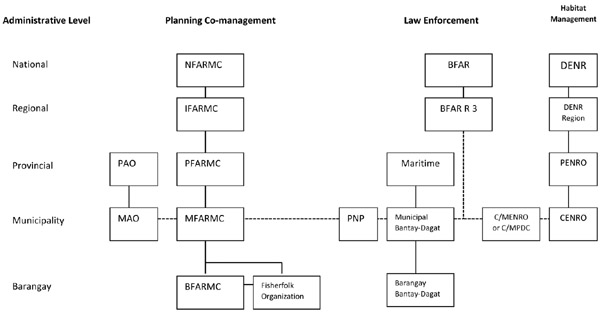

The Philippines is one of the early adopters of co-management in natural resource management and decentralization in governance (Ratner et al 2012). BFAR under the Department of Agriculture directly manages commercial fishing and aquaculture, and the local government units (LGUs) manage the municipal fisheries. Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Management Councils (FARMCs) from the national to the barangay (the smallest unit of Philippine governance), composed of fisherfolk, local government units, regulatory agencies and civil society representatives, are mobilized to help in the planning and policy initiatives for fisheries development. Bantay Dagat (Sea Guards), composed of volunteers from the municipal and barangay level, were formed to help with the enforcement of fisheries laws and to protect marine resources (Figure 11.3).

In MMORS, the FARMCs are only organized in two coastal barangays of Meycauayan and in all barangays of Obando. A farmers’ organization composed of farmers and fishpond operators was formed in Marilao. Valenzuela does not have an active FARMC or fisher organization. Some of the challenges of FARMCs and Bantay Dagat include lack of logistical resources, weak enforcement and application of the fishery law and lack of FARMC engagement in local planning and policy development.

Although it’s the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) function to manage, conserve and protect the various ecosystems, they also work closely with BFAR (for coastal and marine ecosystems) and local government units in implementing these functions. One of the policies that promotes the integration of efforts for river management is the Clean Water Act of the Philippines (RA 9275). This Act encourages the creation of Water Quality Management Areas (WQMA) to consolidate efforts to rehabilitate water resources, as well as to protect the livelihoods of stakeholders along the river system. WQMA adopts an integrated river basin approach to water management through the formation of WQMA governing boards – these streamline the different agencies’ and local government units’ efforts on river rehabilitation. Before the enactment of this Act, there were few opportunities where the resource stakeholders could interact.

MMORS fishery industry: a vulnerable sector

The changes in the natural, social and governance system in MMORS, primarily water pollution but including national and regional social-ecological changes, increased the vulnerability of the fisheries sector. The impacts of these changes range from reduced fish catch and proliferation of invasive species, to changes in fish farm management, land use, and the roles of women in local fisheries.

Although Bulacan province remains one of the main sources of aquaculture products in the Philippines, the total production and growth rate have declined since 2002. The proliferation of invasive species, specifically the black chin tilapia (Sacrotherodon melanotheron), is a major concern in MMORS. This species is more resilient to poor water quality, competing with other tilapia species and bangus (Chanos chanos) for food. This affects the carrying capacity of the fishpond. The black chin tilapia is sold at less than half a dollar compared to two US dollars per kilo for traditional species such as the native tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) and pla-pla (O. niloticus).

Due to flooding, ground subsidence and reduced profits from the fishery, earth-diked fishponds are being transformed into netted fishponds. This type of fishpond reduces the capacity of the fish farmer to control the water quality of the pond, prevent the entry of invasive fish species and prevent fish losses and increases the risk of fish theft. Food security is also an issue in coastal communities due to reduced fish diversity and fish catch. Small-scale fishers and fish farmers are also more vulnerable to pollution and natural calamities because they do not have sufficient capital and institutional support to sustain their livelihood.

Another impact of the changes in the river quality and level is its effect on land use. Former fishponds are now being sold by their landowners and converted into residential or commercial areas. Some areas were converted into a sanitary landfill. Furthermore, the higher cost of inputs and water treatment changes the fishpond ownership and management. These are now concentrated into fewer people with the capital to continue fish farming. The local fishers have become caretakers or laborers to the operators.

These changes have also affected women’s roles in fish farming. Women do not engage in fish farming of netted fishponds because it requires more manual labor and poses higher risks, like drowning. The river pollution has also caused decreases in fish found in areas near the shore because it is believed that capture fishers now need to go farther to other coastal towns.

Most importantly, the fisheries sector commonly located in downstream areas are severely affected by the industrial and agricultural development in the upstream areas. Although the downstream communities also contribute to the pollution challenges in MMORS, heavy metal pollution comes primarily from industries located upstream. The local fishery sector has now been mobilized by the local and regional agencies for co-management and co-planning, but the challenge is for the conflicting resource users to come up with a common plan to solve this concern. Aside from external stakeholders, fishers and fish farmers are at the mercy of the traders for the price of their catch.

Current responses and challenges

The main issue in this study is the water pollution of MMORS that affects the quality and sustainability of the fishery livelihoods, posing health risks to fish consumers. Water bodies and other natural resources do have the capacity to regenerate. However, the current status of the MMORS, particularly in the upstream areas, has already crossed this threshold. Eutrophication and apoxia are evident in some parts of the river near the industries. Fishing is an industry that is highly dependent on natural processes and changes. Fishers and fish farmers have learned to adapt through local environmental knowledge, local innovations and changes in fishery practices and household consumption. Despite the poor water quality, these fish farmers have implemented adaptations and responses as a means to maintain their fishing livelihoods. Examples of their short-term responses include changes in fish farm management (use of nets vs. earth dikes), use of technology (pumps and aerators) depending on their financial capacity, use of less expensive inputs during the grow-out period and introduction of commercial feeds near the harvest period to promote growth and early harvest to take advantage of competitive prices and to reduce loss from flooding during the rainy season. These short-term adaptations helped them sustain their fish farms, albeit at reduced profits. However, these are not fully effective in addressing the water pollution problems and sustainable fish farming along the MMORS.

Furthermore, these adaptations were done only by the individual fish farmer and have yet to be institutionalized at the sectoral level. Long-term responses to river pollution and its impacts on fish farming include institutional capacity building. The FARMCs could serve as a venue for an institutional approach to integrate the interventions to improve fish farm management and to resolve the river pollution issue. However, not all areas have FARMCs, despite the policy requiring their formation in coastal and fishing communities. There is a lack of incentives and material support to mobilize and sustain the FARMCs. These prevent the engagement of fishers in local development planning and implementation.

At the governance level, the short-term responses include regular river quality monitoring (RQM), including biota sampling to validate the presence of heavy metals in the fish and shellfish in the area. The RQM results helped put pressure on government agencies and local government to implement projects and support research to rehabilitate the river system. However, the government regulatory agencies and local officials have expressed concerns about reporting the results to the public because this may affect the fishing livelihood and economy of the areas.

The long-term responses include the declaration of MMORS into a WQMA because RA 9275 promotes the integration of water resource rehabilitation through the formation of WQMA. This response would address the fragmented interventions of different agencies and local government units. In 2008 the MMO became one of the first areas declared a WQMA. A WQMA governing board is composed of representatives from regional regulatory agencies, local government units, academia, civil society and industry from the areas covered. From 2005 to 2010, local stakeholders, together with ADB, JICA and Blacksmith Institute, focused on the formation of multi-sectoral groups, baseline research, capacity building and pilot testing of cost-effective technologies for gold smelting and tannery industries.

Upscaling and sustaining these initial gains is necessary to ensure effective river rehabilitation. Some of the limitations include political and financial support to MMO WQMA projects, weak conflict resolution between LGUs and different agencies, weak law enforcement and lack of dedicated staff to coordinate and provide logistical support. In addition, there are no representatives from fishery organizations in the MMO WQMA governing board. Although BFAR is part of the MMO WQMA, the livelihood concerns of the industry are not well integrated in their plans.

The government’s current fisheries program covers a wide range of approaches to address fishery issues in the area. The projects include database management, livelihood assistance through technology, equipment and fishery processing development, capacity building and coastal resource management. Nevertheless, there is still weak integration and coordination among the objectives of providing sustainable livelihoods, such as food security, natural resource conservation and rehabilitation and social equity. There is also a lack of focus on gender and intra-generational concerns in fishery programs, such as the engagement of women in fisheries production systems and technical fisheries education for youth in coastal areas.

Practices that work and areas for improvement

In general, the short-term responses implemented to address the main issue of river pollution in MMORS have similar costs and benefits. Currently, the cost of the long-term responses, particularly at the fish farmer level, are higher compared to their benefits due to lack of institutional support and mainstreaming in regular fisheries and development policies and programs. The insights and lessons gained from this case study are discussed next.

The whole-of-policy cycle approach

The Philippines has enacted a number of major national laws on fisheries and water resource management. These laws served as an institutional basis to intensify initiatives at local to national levels to address major challenges in these sectors. However, one of the gaps is enforcement and localization of these laws through municipal fisheries codes and integration with local development plans/programs of fisheries and water resource management. Changing priorities every new political term (three to nine years in the Philippines) is also a limitation in sustaining the implementation of such a policy or plan. Monitoring and evaluation of policies at least every three years should also be done to check the relevance, effectiveness and impacts to target sectors or specific challenges that the policy tries to address.

Livelihood and ecosystem-based approach to fisheries and water resource management

The current river rehabilitation and fisheries development approaches heavily focus on enforcement, but impacts to livelihood dynamics are not often incorporated in these plans and projects. Coastal community members see the river and marine ecosystem primarily as a source of resources and livelihoods; however, the data and information on the impacts of their activities and those of other sectors and industries are not fully disclosed. A mechanism should be set in place to promote understanding and dialogue between the different sectors. Conflict resolution systems should also be institutionalized.

Co-management and multi-stakeholder engagement

Engaging stakeholders is vital for effective natural resource management. Challenges include maximizing the inputs of stakeholders in discussions and processes and sustaining their active participation. Accountability of multi-stakeholder groups for the performance and achievement of targets for river rehabilitation should be established, particularly if inaction will lead to greater human and environmental risk.

Co-management is integrated in the current fisheries and natural resource management programs of the Philippine government. There is also heightened awareness and appreciation for the need to engage local stakeholders, evident in the formation of local councils and their role in development planning and implementation. However, each stakeholder’s role should be clearly stipulated, and they should be facilitated through technical and skills training, logistical and financial support, political support and venues for sharing lessons learned within their sector and among different stakeholders.

Scientific and local ecological knowledge integration

There are numerous studies and projects by local and external experts and organizations to support the initiative to rehabilitate the MMORS WQMA and sustain fisheries livelihoods in the area. These should be maximized to guide local planning and development. Local fishers, fish farmers and their organizations also have rich experiences and local ecological knowledge about the river system and fisheries. The adaptive capacities of fisherfolk helped in making short-term responses successful in terms of sustaining the fish farm operation.

The national and local fisheries policies provide enabling mechanisms to encourage stakeholder engagement in fisheries and river rehabilitation. Pilot studies and projects by private and civil society in partnership with fisheries and multi-stakeholder groups could also be scaled up and mainstreamed. There is a need to strengthen the institutional mechanisms for these types of collaborations through the use of more participatory tools and approaches to projects and research.

Conclusion

The main issue of interest in this case study is water pollution in a river system in the Philippines affecting the fisheries and fish farming in the area. This issue is not unique to the Philippines. Pollution is increasingly a major concern in regional and global water resources. It is an indication of the conflicting uses and fragmented values of various stakeholders in a common pool resource such as a river system.

The I-ADApT decision support tool guided the researchers of this case study in evaluating the whole-of-system concerns of river pollution and fisheries in MMORS. This tool facilitated a better understanding of the dynamics within and across the natural, social and governing systems in MMORS. The case study showed how legacy development and responses can affect the long-term river water quality and exposed the vulnerability of the MMORS fishing industry to these changes. The tool also highlighted current capacities of the system in terms of adaptation, governance and strategies, which could be further improved and expanded. These include the use of a whole-of-policy approach, co-management and multi-stakeholder engagement, including their accountability, and scientific and local ecological knowledge integration.

Thus, initial lessons, gains and limitations from this case study can serve as input to similar cases and challenges on river pollution elsewhere. As noted by the woman fishery leader quoted earlier, having received just the negative side of development, there is a need to balance it with the positive. This way, the marginalized sectors of society like fish farmers and poor communities along the river system will no longer experience only negative impacts. Providing cases to share lessons, insights and a framework to assess the whole-of-system approach is a move towards this end.

Acknowledgements

This chapter is based on the following projects supported by international funding agencies and local stakeholders: Clean the Marilao-Meycauayan-Obando River System Project (2008–2010) funded by Coca-Cola Foundation, Inc., and Green Cross Switzerland; Reducing Mercury Contamination in the Marilao-Meycauayan-Obando River System (2009–2010) funded by the Asian Development Bank; Protecting Livelihoods, Ecosystem and Human Health in the Philippines supported by the Hong Kong Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC); post-graduate research on “Dynamics of Social-Ecological Traps: The Case of Small-Scale Fisheries in the Philippines” of Jennifer Marie Amparo in Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University supported by the Australia Awards Scholarship; and logistical and technical support of the MMO WQMA board during the conduct of the projects. MMO WQMA board is composed of regional (Region 3) regulatory agencies such as Environmental Management Bureau – Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR-EMB); Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR)-Department of Agriculture (DA); Department of Health (DOH); Department of Science and Technology (DOST); Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG); the provincial government of Bulacan; the local government units of Marilao, Meycauayan, Obando, San Jose Del Monte, Sta. Maria, Valenzuela and Caloocan; and academe and industry representatives

Note

References

Alfafara, C., Maguyon, M.C., Laurio, M.V., Migo, V., Trinidad, L., Ompad, E., Mendoza, M.D., et al. (2012). Scale-up and operating factors for electrolytic silver recovery from effluents of artisanal used-gold-jewelry smelting plants in the Philippines. Journal of Health and Pollution 2: 32–42.

Blacksmith Institute. (2007). The world’s worst polluted places. New York City. www.blacksmithinstitute.org.

Blacksmith Institute. (2009a). Reduction of mercury and heavy metal contamination resulting from Artisanal Gold refining in Meycauayan, Bulacan River System: Final report. Asian Development Bank, Water for All.

Blacksmith Institute. (2009b). Clean the Meycauayan-Marilao-Obando river system. Los Banos, Laguna, Philippines. www.uplb.edu.ph

Bundy, A., Chuenpagdee, R., Cooley, S.R., Defeo, O., Glaeser, B., Guillotreau, P., Isaacs, M., Mitsutaku, M. and Perry, R.I. (2016). A decision support tool for response to global change in marine systems: the IMBeR-ADApT Framework. Fish and Fisheries 17: 1183–1193.

Cabral, R., Cruz-Trinidad, A., Geronimo, R., Napitupulu, L., Lokani, P., Boso, D., Alino, P., et al. (2013). Crisis sentinel indicators: Averting a potential meltdown in the Coral Triangle. Marine Policy 39: 241–247.

Castello, L., Viana, J.P., Watkins, G., Pinedo-Vasquez, M. and Luzadis, V.A. (2009). Lessons from integrating fishers of arapaima in small-scale fisheries management at the Mamirauá Reserve, Amazon. Environmental Management 43: 197–209.

Center, W. (2010). Gender and fisheries: Do women support, complement or subsidize men’s small-scale fishing activities? In: WorldFish (Ed.) CGIAR and WorldFish Center (Vol. 2108). Penang, Malaysia: WorldFish Center.

David, C.P.C. (2011). Pollution loading in the Marilao-Meycauayan-Obando River System. Paper presented at the EAS Conference http://pemsea.org/eascongress/international-conference/presentation_t6-2_david.pdf

Dowling, J. (2011). ‘Just’ a disherman’s wife: A post structural feminist expose of Australian commerical fishing women’s contributions and knowledge, ‘Sustainability’ and ‘Crisis’. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge, UK.

Hughes, S., Yau, A., Max, L., Petrovic, N., Davenport, F., Marshall, M., Cinner, J.E., et al. (2012). A framework to assess national level vulnerability from the perspective of food security: The case of coral reef fisheries. Environmental Science & Policy 23: 95–108.

Israel, D.C. and Roque, R.M.G.R. (1999). Toward the sustainable development of the fisheries sector: An analysis of the Philippine fisheries code and agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act. Philippine Institute for Development Studies, Discussion Paper Series No 99–01, 88 p.

Malenab, M.C.T., Visco, E.S., Torio, D.A. and Amparo, J.M.S. (2013). Fish farm management study. Social Development Services, College of Human Ecology. University of the Philippines Los Banos, Los Banos, Laguna.

Perez, M.L., Pido, M.D., Garces, L. and Salayo, N.D. (2012). Towards sustainable development of small scale fisheries inthe Philippines: Experiences and lessons learned from eight regional sites. Penang, Malaysia. http://pubs.iclarm.net/resource_centre/WF_3225.pdf

Philippine Judicial Academy. (2012). Citizen’s handbook on environmental justice. Philippines: Philippine Judicial Academy.

Ratner, B.D., Oh, E.J.V., and Pomeroy, R.S. (2012). Navigating change: Second generation challenges of small-scale fisheries co-management in the Philippines and Vietnam. Journal of Environmental Management 107: 131–139.

Rola, W.R. (2007). Economics of aquaculture feeding practices: The Philippines. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 505: 121.

Siason, I.M., Tech, E., Matics, K.I., Choo, P., et al. (2001). Women in fisheries in Asia. In: Williams, M.J., et al. (Eds.) Global symposium on women in fisheries. ICLARM – The World Fish Center, Penang, Malaysia, pp. 21–48.

Weeratunge, N., Béné, C., Siriwardane, R., Charles, A., Johnson, D., Allison, E.H., Badjeck, M.C., et al. (2014). Small-scale fisheries through the wellbeing lens. Fish and Fisheries 15: 255–279.

World Bank. (2008). Small-scale capture fisheries: a global overview with emphasis on developing countries. PROFISH series. World Bank, Washington, DC.