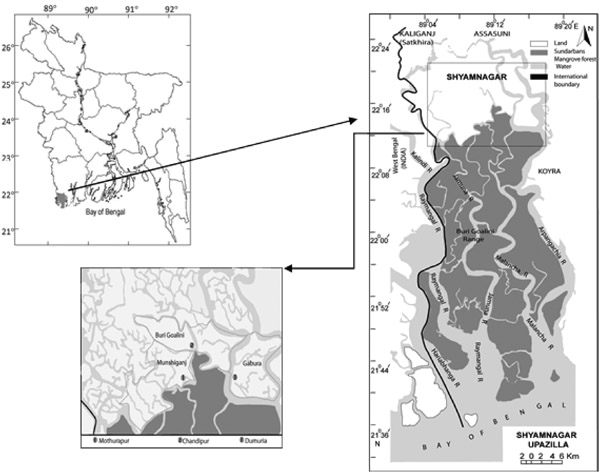

Figure 12.1 Map of the three study areas in the Sundarbans region of Bangladesh

Rapid environmental change and its impacts on human society and vice versa is a growing concern. Climate change and different anthropogenic disturbances affect natural systems, which affects their ability to function and deliver goods and services on which humans depend for their survival and well-being. The coastal zone is the focal point of changes at which different events originating from land and sea interact. Globally, in recent decades the coastal zone has experienced unprecedented social, cultural, economic and environmental challenges from the combination and interaction of different processes. This situation is particularly devastating because of high population density at the coast where heavy exploitation of resources and rapid development activities take place (Bundy et al. 2016). Thus any disturbance has negative impacts on the livelihoods of the populations.

The coastal zone of Bangladesh faces multiple challenges that threaten its ecosystem and production processes and dependent livelihoods. The geographic setting, hydrological, morphological, geophysical and biophysical characteristics of coastal areas shape the conditions and the challenges these areas face, which are compounded by widespread poverty and the poor asset base of coastal residents. Coastal communities continuously attempt to adapt to changing situations, such as when they suffer several shocks within a short period and/or multiple simultaneous pressures. Consequently, vulnerability becomes starkly apparent, making it increasingly hard for any individual to cope (Islam and Chuenpagdee 2013).

Recently, the southwest coast of Bangladesh has been affected by cyclones such as Sidr (November 15, 2007) and Bijli (April 18, 2009). On May 25, 2009, the region was struck by another tropical cyclone, Aila, that generated a storm surge 3 meters above the normal tidal level and devastated a major part of the Sundarbans mangrove ecosystem. The cyclone claimed 190 lives, injured 7,000 people and caused US$170 million worth of economic damage (UNDP 2010). The loss of fisheries resources of the Sundarbans was immense. Salt water intrusion by the cyclone caused fish eggs and larvae to suffer osmotic stress, resulting in high mortalities. Huge numbers of people who depend on the Sundarbans became destitute and had to rebuild their livelihoods from scratch. Because natural resources were destroyed, dependent coastal people were desperate to exploit the dwindling resources, which further affected the sustainability of the mangrove ecosystem.

Responses are taken continuously by relevant parties to overcome threats, stress and pressures, yet identifying the most appropriate responses at a given time to given circumstances remains a challenge (Bundy et al. 2016). Using the case of Cyclone Aila, this study describes the changes of the Sundarbans and related systems and evaluates the various responses to improve decision making when dealing with such situations, including effective allocation of scarce resources. Using the I-ADApT framework as an analytical tool has multiple benefits. The framework enables systematic identification of factors that facilitate changes, of possible preventive options and of the conditions under which these options are feasible. This framework adopts an interdisciplinary approach that takes account of the effects of various stressors on the linked natural and human systems and incorporates the vulnerability of these systems (Bundy et al. 2016).

Information was collected through an extensive review of the literature, with empirical fieldwork conducted in three fishing villages situated adjacent to the Sundarbans mangrove forest in Satkhira district of Bangladesh (Figure 12.1). The main fieldwork was conducted in 2011, with follow-up data collection through telephone interviews with 15 key informants in 2015.

The Sundarbans is the largest mangrove ecosystem on earth and stretches across Bangladesh (60 percent) and India (40 percent) along the coast of the Bay of Bengal. In the Bangladesh Sundarbans, approximately 100,000 to 200,000 people work in the area for at least six months, and the number of people entering the forest in a year can be as high as 3,000,000. Of these, about 25,000 people work in fish drying and 60,000 to 90,000 people in shrimp post-larvae collection inside and around the Sundarbans (Abdul 2014). The livelihoods of resource harvesters of the Bangladesh Sundarbans are characterized by high levels of poverty in terms of income and human development. Women are particularly underprivileged and marginalized, with minimum access to income, livelihood opportunities, education and healthcare. Moreover, there is no mobilization and organization of resource extractors in order for them to be recognized as stakeholders in the management of the Sundarbans (Mitra 2000).

The Sundarbans region is highly exposed and vulnerable to climatic disaster risks. The region is also a locus of extreme poverty. In 2007 one of the most devastating cyclones in Bangladesh history, Cyclone Sidr, hit the region and left more than 3,000 dead, affecting the lives of more than 4 million people and leaving a trail of devastation, including destroyed houses and physical infrastructure, flattened standing crops, dead livestock, contaminated water and disrupted road connections. About 36 percent of the total area of the Sundarbans mangrove forest was damaged by this super cyclone (CEGIS 2007) (Figure 12.2). Many of these areas had not recovered when Cyclone Aila hit 14 districts on the southwest coast of Bangladesh on May 25, 2009. It was the second major blow for the region in less than two years. Although Cyclone Aila was not as strong as Sidr and the initial death toll was considerably lower, Aila has had a devastating long-term impact because embankments which were breached during the storm surges remain unrepaired and affected villages were regularly flooded during high water.

People continue to live on embankments – the only place above water – without sufficient food, water, shelter or protection. In the study area, the main economic activities (e.g. fishing, agriculture, shrimp farming) were shattered by this extreme event. People accustomed to going deep into the forest and collecting fish and crab, fuel woods, snails and oyster, honey and wax, wood and timber for their own use and for sale have been affected by the cyclone. To forestall further degradation, the government of Bangladesh (GoB) banned the extraction of wood resources to conserve what remained of the forest. This led many bawalis (timber collectors), whose livelihoods were already strained by the impacts of these cyclones, to turn to fishing as an additional form of income generation (Islam and Chuenpagdee 2013). According to Mallick et al. (2011), almost 80 percent of workers lost their jobs, 40 percent had to change their profession and at least one person among the affected family members looked for relief aid and rehabilitation support either from the government and/or development organizations.

Mangrove ecosystems are recognized as being highly productive (UNEP 2014). The Sundarbans is a globally significant UNESCO World Heritage and Ramsar site. The forest was declared a reserve in 1869, and since then the physical boundary of the Bangladesh Sundarbans has hardly changed. However, overexploitation of forest resources is a major concern. Increased salinization due to withdrawal of fresh water from upstream Farrakka barrage in India, irregular rainfall and introduction of brackish water shrimp culture are additional major challenges. Increased salinity may cause changes in fish species distribution and loss of fresh water species in the region. Because there are many export-oriented commercial shrimp farms in the periphery of the forest, eutrophication and biological pollution can happen.

The Sundarbans ecosystem was negatively affected by Cyclone Aila. According to fishers’ perceptions, the cyclone struck during the breeding period of many commercially important aquatic species, and hot water associated with the cyclone ‘burned’ the eggs and larvae of many species. As a consequence, catches of many species were reduced substantially (Shamsuddoha et al. 2013). Fishers lost their fishing gear and crafts, and their capacity to fish was crippled (UN 2010). Although no data are available about the disruption of ecosystem functions of the Bangladesh Sundarbans, research in similar ecological settings and in the Indian Sundarbans suggest that the ecosystem function of the Bangladesh Sundarbans may have been negatively affected by the cyclone. After Cyclone Aila, the level of salinity became unstable in the forest, creating an unfavorable situation for mangrove species. The banks of rivers and canals lost a noticeable amount of land that settled onto river beds, which resulted in decreases in channel depths and reductions in the refuge, breeding and nursery grounds of mangrove-related fish species. Further, sediment carried by tidal surges was deposited on the forest floor as the surge receded, causing mangrove mortality by interfering with root and soil gas exchange. Sedimentation also decreased breeding and degraded the nursery grounds of mangrove riverine systems. It is estimated that 40 percent of the forest was destroyed by the cyclone. The most affected mangroves had broken stems or were uprooted due to massive erosion or died due to prolonged inundation (Figure 12.2).

Cyclone Aila inflicted enormous damage to the Indian Sundarbans as well. Significant changes in fish assemblages in the Indian Sundarbans after the cyclone included a reduction of species diversity and variation in their seasonal patterns of abundance. Although these changes were mainly attributed to increasing temperature and salinity, Cyclone Aila was also responsible to a certain extent (Mukherjee et al. 2012). Bhattacharya et al. (2014) concluded that mesozooplankton distributions in the Indian Sundarbans might have been affected by Cyclone Aila, as the extreme event could remove diverse feeding guilds of mesozooplankton, consequently causing imbalance in trophic interactions, altering food web structure and subsequent changes in ecosystem function and fisheries productivity.

In the study areas, fishing was the most prominent occupation of 67 percent of households, and crab catching was the main occupation of 14 percent of the population (Getzner and Islam 2013). Post-larvae of shrimp and prawn were collected by about 70 percent to 75 percent of the households living on the river bank bordering the forest. Other major activities in the region were timber collection, fodder exploitation, honey collection and nypa palm exploitation from the forest. Some people worked as day laborers in aquaculture, agriculture and tourism. A national study indicated that 65 percent of the populations of Shyamnagar and Satkhira districts were below the lower poverty line (UN 2010). Limited ownership of different capitals restricted their livelihood space and reduced well-being and resilience. High dependency on mangrove forests entail livelihood insecurity in case of the collapse of fisheries stocks. Thus fishers were more vulnerable to extreme events and disasters.

The Sundarbans communities were already in a distressed situation due to Cyclone Sidr in 2007 when Cyclone Aila slammed into the region and caused massive destruction. This ‘double blow’ created long-term impacts to the communities who depend on the Sundarbans for their livelihoods. Cyclone Aila caused enormous destruction of local infrastructure and community assets such as housing, fishing boats and gear, decimating the capacity to fish for immediate survival. Moreover, as many failed to pay back previous loans due to losses following Cyclone Aila, micro-credit financial non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have not provided further loans to support re-establishment of their livelihoods. This fall in agricultural, fishing and other mangrove-related activities significantly affected the local labor markets and led to decreased employment opportunities and income for agriculture and fishing wage laborers. Casual laborers found only 7 to 10 days of work per month, compared to 20 to 25 days in a normal year. As a result, food deficiency in the region lasted for four to six months in 2009 (UN 2010). The income of each affected household was decreased by approximately 44 percent (Joint Assessment Consortium 2009), and unemployment increased from 11 percent to 60 percent after the cyclone (Akter and Mallick 2013).

Prior to Cyclone Aila, the majority of people in the affected areas were largely self-sufficient (UN 2010). After the extreme event, there was limited scope for communities (either living on the embankments or for those who returned to their previously inundated land) to re-engage in their previous livelihood, given the dominance of the largely destroyed shrimp industry. Consequently, many people went into mangrove fisheries to secure income and food as opportunities for land-based livelihoods constricted. Local communities, mainly women and children, are involved in shrimp and prawn post-larvae collection that require minimum investment capital. This activity, however, is considered environmentally destructive as it kills larvae of other non-target aquatic species. The loss of fisheries negatively affected other fishers in the area. The school dropout rate was high because many households employed child labor as one of the adaptation strategies to help extract forest resources.

The Sundarbans is governed by a hierarchical system. The Department of Forest has top-down management of the Sundarbans with no involvement of the local people and perceives resource management from its own perspective. A specialized division called the Aquatic Resources Division (ARD) within the department is responsible for management of aquatic resources of the Sundarbans. The long-term objectives of forest management are to ensure adequate supplies of forest products while maintaining the sustainability. The primary goal of the ARD is to put into place an effective management system for aquatic biodiversity (fishes, crustaceans and mollusks) of the Sundarbans, to protect vulnerable species and to allow sustainable harvesting of fish resources over the long term.

A number of regulations and policy directives are in place to achieve the objectives of fisheries management in the Sundarbans. However, the management regimes are primarily revenue oriented, although a number of legislations provide prohibitions and restrictions regarding Sundarbans resources. To allow breeding of species, seasonal bans on exploitation are imposed on a number of commercially important fish species. There is a regulation on the collection and export of live crab that prohibits catches during their breeding season. All gears operated by fixed engine boats are permanently prohibited. Fine-mesh gears which catch larvae of fish and shrimps are prohibited. Eighteen canals are permanently closed to fishing to allow fish to breed. Fishing without a permit is illegal. However, breaches of these regulations are rampant as many people are involved in illegal logging, poaching of wildlife and using banned and destructive fishing practices such as poison and fine-meshed nets and catching undersized (e.g. shrimp and prawn postlarvae) and berried (e.g. crab) species (Islam and Chuenpagdee 2013). Fishers complain that they need to pay bribes to forest officials in order to fish in the forest. Thus their already insufficient income becomes further dissipated. To compensate for this additional cost, fishers resort to illegal fishing and overexploitation of forest resources, which affects the sustainability of the mangrove forest.

In terms of power relationships, the patron–client relationship is dominant in the communities that wield the most social power in the area. Many fishers take loans (dadon) from local patrons to buy fishing gear or to purchase food and other household items. It is estimated that more than 95 percent of the working capital of Sundarbans resource extractors is from dadon (Islam et al. 2011). In return fishers sell their catches at prices lower than the market price due to contractual obligations. Around 34 percent of the Sundarbans products are traded within a 20-km band surrounding the Sundarbans. About 63 percent of the catches are traded to other parts of the country, and around 3 percent (mainly live crab) are exported to foreign countries. A series of intermediaries exist in the marketing of Sundarbans products that causes rent dissipation, for example, in the case of hilsa shad (Tenualosa ilisha), fishers get around 63 percent of the price that consumers pay (Islam et al. 2011).

After facing the devastation of two consecutive cyclones and being the worst affected, many fishers left the fishing profession. Some of them migrated temporarily in the immediate aftermath but returned to the coast after a short time. Sometimes it was only the men who migrated, leaving women and children behind to survive on small earnings by catching shrimp seedlings using stationary gear (estuarine setbag net, push and pull net). This environmentally destructive exploitation put further pressure on the mangrove fishery. As the productivity decreased, many fishers switched target species (e.g. from fish to crab). Fishers who remained in the area often reduced their food purchases and compromised their food consumption by having fewer meals per day (UN 2010). Other responses included reducing the frequency and quality of meals, searching for wild foods from the forest to replace normal diets, using savings to meet basic needs and taking loans from NGOs. Many fishers were unable to get back to their profession as their productive assets and houses were damaged or destroyed. Most of them were living on broken embankments, relying on relief distributed by governments and NGOs. Starting from scratch, fishers as well as other professional groups were at first involved in shrimp and prawn post-larvae collection, as it requires only net or mosquito curtains with no fishing skills. Other forest-goers also became involved in fishing, as it requires little capital, putting further pressure on the resources.

Although community responses were mostly at the local level, their consequences were felt at regional and national levels. A mass exodus of Sundarbans communities to nearby cities of Satkhira and Khulna, even to Dhaka, occurred because their villages had been inundated by tidal flows and their means of survival were mostly lost. In these destinations, they lived in slum areas and were involved in daily labor and rickshaw pulling to eke out a living.

Different ministries of the GoB, such as the Ministry of Disaster Management, the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock and the Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperative (LGRD), are actively involved in recovery in the region. Immediately after Cyclone Sidr, the Department of Fisheries banned all kinds of wood, honey and golpatta extraction from the forest to allow natural regeneration of mangroves. Consequently, those people who were dependent on woodcutting switched to fishing. Thus, fishers in the Sundarbans increased tenfold after Cyclone Aila (Islam and Chuenpagdee 2013). Because the Sundarbans is a UNESCO World Heritage as well as Ramsar site, relevant agencies were also concerned regarding sustainability of the forest. In support of GoB, a number of local and international development agencies were involved in the rehabilitation of mangrove communities after the disaster of Cyclone Aila, where a section of local communities also provided labor. The GoB also provided relief support for immediate survival of the affected communities and to generate income. The long-term objective was to restore the health of mangrove ecosystems to their previous states before cyclones Aila and Sidr struck by leaving the forest to recover itself. To a lesser extent, replenishment programs were implemented in the peripheral zone of the forest. The governing system responses were intended to increase resilience of both the social and natural systems of the forest.

In terms of management measures, the government continued the ban on the exploitation of wood resources from the forest that was imposed after the Cyclone Sidr. There was no specific management option for aquatic resources in the context of Cyclone Aila’s negative impacts. After the cyclone, the GoB distributed relief assistance, including food, cash, drinking water, emergency medicine and other non-food materials to the affected communities and later initiated reconstruction efforts that continued until 2013. Different NGOs distributed fishing gear and gave training on aquaculture. A major part of the GoB assistance was distributed under existing networks such as Vulnerable Group Feeding, which is targeted to vulnerable people in society. Some of these assistance programs continued until 2010. The government also rolled out a ‘Cash for Work’ program for the rehabilitation of physical infrastructure in the affected districts. The program generated post-cyclone employment to support the normal livelihood strategies of vulnerable households, as well as to stimulate the local economy.

Responses also occurred at international and local levels. International donor organizations provided relief materials. NGOs and other international organizations are still working to improve the current situation. Yet their efforts have not been very successful due to limited funds, shortcomings of the operational system or lack of coordination among NGOs for efficient use of these funds. The objective of the response was the immediate survival from the disasters through alternative livelihood options in other economic sectors to sustain income to meet food security and housing needs of the affected people.

On a positive note, a humanitarian disaster was averted without any spread of disease and mass starvation. Other aspects of human well-being were severely affected by the cyclone, making it difficult for the area to recover. Many fishers still suffer food insecurity due to inadequate income from fishing. Without much scope for alternative income generation, dependency on the Sundarbans fishery further increased. Many fishers took their children away from school and involved them in the collection of shrimp seedlings to reduce schooling costs and increase family incomes.

With regard to long-term results, the negative impacts of Aila were long-lasting on the livelihoods of fishing communities. Many fishers permanently left fishing after migrating to the city. A majority of fishers returned to their profession, but as species abundances fluctuate, fishers often change their target species. Through interaction with relief organizations, many fishing households realized the importance of education in obtaining other economic opportunities. The sufferings of communities were long, even after four years of the disaster. Thousands of people still live in the coastal belt of Khulna and Satkhira districts in makeshift tents and are only just returning to their homes due to the delayed reconstruction of damaged embankments, parts of which were broken during Cyclone Aila (Oxfam 2012).

Relief support from GoB and different organizations helped with the immediate survival of communities. The open-access nature of the Sundarbans allowed immediate access to fishing so that many fishers could sustain their incomes, although in moderate amounts. In terms of limiting factors, most of the rehabilitation activities were short term. Very few initiatives focused on the long-term resilience of the communities. In terms of cost–benefit comparisons, the prohibition of wood collection caused the loss of income options for some; thus social costs were higher. However, ecological benefits far outweighed the costs because they enhance long-term ecosystem services to the communities.

The responses of the governing system were inadequate for enhancing the resilience of the social and natural systems. GoB efforts to reconstruct coastal embankments were delayed almost two years after the disaster, and as a result, many fishing hamlets were regularly flooded by tidal flows. Fishers had to live in makeshift structures built on shattered embankments. The governing response did not explicitly address the sustainability of fisheries resources with respect to the impacts of the disaster. The resilience of fishing communities was addressed as part of the total population. Apart from providing relief for immediate survival, government responses were inadequate and delayed. There was no compensation scheme for loss of livelihood options from the forest. Initially, the government did not appeal for international assistance (UN 2010). After a delay, on June 19, 2009, the Bangladesh government made an appeal to the international community for reconstruction work and rehabilitation. Different humanitarian agencies participated in rehabilitation and livelihood recovery programs in the areas affected by Aila. However, coordination was weak. Most of the agencies implemented stand-alone programs, resulting in overlapping services in some areas, whereas other areas remained underserved. The recovery process was interrupted several times by delays to the repair of embankments. So far, there has been no formal evaluation of the responses. The relief and reconstruction work has not been sufficient, and people had to live in vulnerable conditions for longer than expected.

The GoB moratorium to enable regeneration of mangrove species was implemented, which helped to restore the forest to a certain extent. The cost of implementing a mangrove management plan in response to Cyclone Aila was less, as no extra resources were allocated to monitor the ban on wood exploitation. The successful regeneration of mangrove forests to satisfactory levels indicate the success of the governance responses to some extent. However, as there were no specific short-term responses for the loss of the mangrove fishery, degradation of fishery resources continues. Two types of factors determined the outcome of the responses. The government policy of not exploiting forest resources or the removal of damaged trees was a positive factor which allowed regeneration of mangroves, as well as provided food for aquatic resources. In terms of barrier factors, without the payment of ecosystem service schemes, many forest-goers continued their profession illegally. From a cost–benefit comparison, the benefits of mangrove enhancement have been achieved, although it caused increased pressure on fisheries resources. Ultimately, mangrove resources played an important role in the survival of Aila-affected, mangrove-dependent communities. The cost of rehabilitation of affected communities was much higher. However, such responses acted as a buffer against widespread livelihood crises after exposure to Cyclone Aila.

In response to repeated extreme events in the coastal zone, fostering policies for appropriate mitigation and adaptation to changes using limited resources is a challenge for Bangladesh. Such responses require timely, effective and well-coordinated actions with all parties at multiple levels. In designing appropriate responses, it is important to consider the inter-dependency of the three linked systems. The analysis of the impacts of Cyclone Aila on the Sundarbans system reveals that the cyclone did transform the three systems in question; however, the different responses were insufficient to make the system resilient to recurring changes. Although the immediate response to the cyclones was to focus on recovery of the mangroves through a ban on timber exploitation, the governance system did not consider the spillover and undesirable effects on fisheries and livelihoods, with more people involved for their own subsistence. Better coordination between GoB and NGOs and among the NGOs’ response and recovery programs could have produced better utilization of limited resources and resulted in equal distribution of services and resources to all affected parties, which would have benefited the entire system. Because the Sundarbans ecosystem is subjected to a complex set of natural, social and/or governance drivers, with responses and interactions occurring at multiple levels and scales, the application of I-ADApT was useful in identifying factors affecting the effectiveness of certain responses. These findings can also help decision makers address issues that threaten resilience and overall human well-being in the context of rapid environmental change.

Abdul, A.M. (2014). Analysis of environmental pollution in Sundarbans. American Journal of Biomedical and Life Sciences 2: 98–107.

Akter, S. and Mallick, B. (2013). An empirical investigation of socio-economic resilience to natural disasters. UFZ Economics Working Paper Series 04/13, Munich Personal RePEc Archive MPRA, Munich, Germany, mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/50375/.

Bhattacharya, B.D., Bhattacharya, A., Rakshit, D. and Sarkar, S.K. (2014). Impact of the tropical cyclonic storm ‘Aila’ on the water quality characteristics and mesozooplankton community structure of Sundarban mangrove wetland. Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences 43: 216–223.

Bundy, A., Chuenpagdee, R., Cooley, S.R., Defeo, O., Glaeser, B., Guillotreau, P., Isaacs, M., Mitsutaku, M. and Perry, R.I. (2016). A decision support tool for response to global change in marine systems: the IMBeR-ADApT Framework. Fish and Fisheries 17: 1183–1193.

CEGIS. (2007). Effect of cyclone Sidr on the Sundarbans a preliminary assessment. Center for Environmental and Geographic Information Services, CEGIS, Dhaka.

Getzner, M. and Islam, M.S. (2013). Natural resources, livelihoods, and reserve management: A case study from Sundarbans mangrove forests, Bangladesh. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 8: 75–87.

Hoq, M.E. (2007). An analysis of fisheries exploitation and management practices in Sundarbans mangrove ecosystem, Bangladesh. Ocean and Coastal Management 50: 411–427.

Islam, M.M. and Chuenpagdee, R. (2013). Negotiating risk and poverty in mangrove fishing communities of the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Marine Studies 12:1–20.

Islam, K.M., Islam, M.N., Mia, M. and Aktaruzzaman, M. (2011). Economics of extraction of products from SundarBans reserve forest. Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Economics 34: 29–53.

Joint Assessment Consortium. (2009). In-depth recovery needs assessment of cyclone Aila affected areas. reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/F6603B7EF22A16B4C125768D004B1190-Full_Report.pdf (accessed uly 3, 2017).

Mitra, M. (2000). The Sundarbans: A riparian commons in search of management. Eighth Conference of theInternational Association for the Study of Common Property. Bloomingdale, Indiana, USA.

Mukherjee, S., Chaudhuri, A., Sen, S. and Homechaudhuri, S. (2012). Effect of cyclone Aila on estuarine fish assemblages in the MatlaRiver of the Indian Sundarbans. Journal of Tropical Ecology 28: 405–415.

Oxfam. (2012). Three years after cyclone Aila many Bangladeshis are still struggling with food and water shortages. https://oxf.am/2t9TKty#sthash.b9tQUu2Y.dpuf (accessed July 3, 2017).

Shamsuddoha, M., Islam, M., Haque, M.A., Rahman, M.F., Roberts, E., Hasemann, A. and Roddick, S. (2013). Local perspective on loss and damage in the context of extreme events: Insights from cyclone-affected communities in coastal Bangladesh. Center for Participatory Research and Development (CRPD), Dhaka.

UNEP. (2014). The importance of mangroves to people: A call to action. van Bochove, J., Sullivan, E., Nakamura, T. (Eds). United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, p. 128.

UN. (2010). Cyclone Aila: Joint UN multi-sector assessment and response framework. www.lcgbangladesh.org/derweb/Needs%20Assessment/Reports/Aila_UN_Assessment Framework_FINAL.pdf (accessed January 22, 2015).