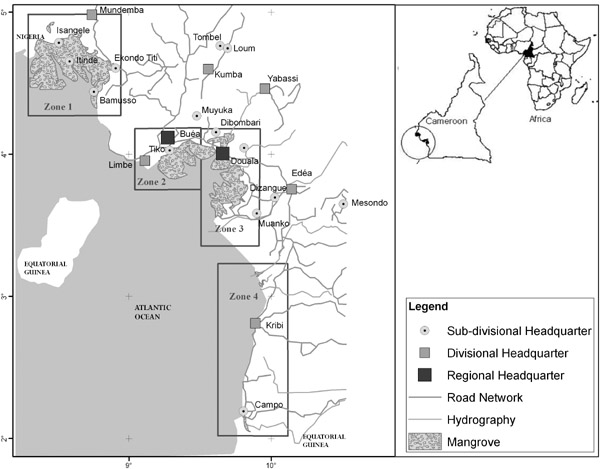

Figure 18.1 Map showing the distribution of mangrove areas along Cameroon’s coast

Mangroves are generally defined as a complex of intertidal wetlands supporting swampy forests and associated habitats that occur in the tropical and subtropical areas (Banque Mondiale 2004). In addition to assaults of tides that they incur every day, mangroves receive land-based runoffs charged with minerals and organic matter (Lafrance and Myre 1994). Their importance in Cameroon stems from the fact that their uses are as varied as their components (Tiotsop 2002). Due to their exceptional biodiversity, mangroves provide an invaluable range of specific goods and services with potential for boosting socio-economic development and alleviating poverty. Their value is notably attributed to their carrying capacity for biodiversity conservation and accretion, thereby enhancing fish growth and productivity of coastal fisheries and, in some cases, offshore fisheries (Choudhury 1997).

Yet, like other parts of the world, Cameroon’s mangroves incur degradation of various kinds and magnitude due to anthropogenic activities (FAO 1994). The rapid population growth in the country, around 2.5 percent per annum between 2010 and 2015 (UNFPA 2013), and the increase in the demand for fuelwood exacerbate human-related pressures, and management and control measures become indispensable. Mangrove degradation is a major threat that, in the long run, could jeopardize mangrove sustainability and thus that of marine fisheries and ultimately the livelihood of the fisheries-dependent communities. The goal of this chapter is to better understand the causes and consequences of this degradation and the governing system of this special ecosystem, using the country’s main mangroves, namely those found around Rio del Rey and Cameroon estuaries.

Cameroon’s mangroves form part of the regional complex of the Gulf of Guinea’s mangroves, stretching between latitudes 2°N to 12°30'N and longitudes 9°30'E to 16°E and are located in two subsystems: the Rio del Rey estuary in the north and the Cameroon estuary1 in the south. The Rio del Rey estuary (zone 1 on the map, Figure 18.1) is situated between the River Akwayafe at the Nigerian border and Njangassa village; the Cameroon estuary (zones 2 and 3) stretches from Cape Bimbia around Tiko to the mouth of the River Sanaga. Forest mangroves in these two estuaries cover an area of about 2,800 km2 (or 280,000 ha) distributed as follows (Zogning 1993; Din 2001; Tiotsop 2002): Rio del Rey estuary (170,000 ha or 60.7 percent of the total area) and Cameroon estuary (110,000 ha or 39.3 percent). Note that zone 4 (or the Ntem estuary) is not included in this case study due to its tiny mangrove area (about 10,000 ha).

The estuaries and the mouths of coastal rivers (Bimbia, Mungo, Wouri, Dibamba and Sanaga rivers) are the main habitats in the two mangrove zones concerned. From the Nigerian border to the mouth of the River Nyong through the Rio del Rey and Cameroon estuaries the coastal area is flat and swampy; it is also characterized by important sediment discharge from rivers, which favor mangrove growth. Marine and terrestrial factors such as microclimate, rainfall, hydrographical network, geomorphology, salinity and the nature of the soils also have a significant impact on growth (Zogning 1993; Din 2001). These factors, coupled with the frequency and duration of inundation, dominant winds and tide dynamics, largely influence the local distribution and succession of mangrove species.

The Rio del Rey estuary is administratively located in the southwest region, mainly in the Ndian division, whereas the Cameroon estuary spans the southwest (Fako division, zone 2) and littoral regions (Wouri and Sanaga-Maritime divisions, zone 3). The two estuaries were selected because of the importance of the mangrove in terms of area covered and magnitude of degradation.

Six indigenous woody species, which are generally grouped as ‘mangrove forests’, have been identified in Cameroon’s mangroves (Zogning 1993; Din 2001; Tiotsop 2002; Ajonina 2008): Rhizophora racemosa, R. mangle, R. harrisonii (referred to as red mangrove), Avicennia germinans, Languncularia racemosa (white mangrove) and Conocarpus erectus. Mangrove forests (red and white mangroves) are locally called ‘matanda’. These species are often found in association with more than 40 other herbal species regarded as ‘companion’ or ‘accidental’ species.

Coastal communities, paramount of whom are the autochthonous populations of various ethnic groups (Malimba, Duala, Bassa, Bakoko, Bakweri, etc.), as well as allochthonous people from the highlands of the west, the northwest and far north regions of the country, coexist with Nigerian, Ghanaian, Beninese and Togolese immigrants. In 2009 there were 4,553 Cameroonian fisheries operating in the area (14 percent of the total) and 28,071 immigrant fisheries operating (86 percent) (MINEPIA/MINADER 2009).

In general, these communities are organized into self-help family and/or development associations of their village of origin, mostly among immigrant fishers. These associations, which are basically informal, can constitute social safety nets in the fishing camps, but there are no cooperative organizations to protect the rights of fishers. A few common initiative groups composed exclusively of Cameroonians have been opportunely established to benefit from subventions and credits (fishing materials and equipment) made available by the government through development projects.

Fishing camps and villages are well structured with a community leader assisted by several other people. Community leaders are themselves supervised by Cameroonian leaders; the latter are administrative auxiliaries charged with solving intracommunity and intercommunity issues. When issues cannot be tackled at the camp level, the camp leader refers them to the competent administrative authorities under which the camp is placed. As such, there is some hierarchy from the community leader to the administrative authority who is territorially competent through the camp leader. However, there is virtually no organization entrusted with decision-making power in the fishing camps and villages.

The institutional framework governing the management of Cameroon’s mangroves is complex and characterized by a multiplicity of decision-making bodies and actors intervening at various levels and in various sectors of activities (MINFOF 2012). These include several ministries charged with sector policy formation, implementation and monitoring and can be grouped as follows depending on the level and magnitude of their interventions on the mangrove:

The key stakeholders include the artisanal fishers in fishing camps and villages, the main group in terms of number, indigenous knowledge and vulnerability, and mangrove woodcutters and sand extractors from neighboring towns, whose growing numbers, although reflecting the crucial role of activities that this ecosystem supports, seriously threaten its sustainability. In fact, the anarchic exploitation of the mangrove adversely affects not only the livelihoods of resource users, but also the coastal population at large, considering the resultant reduction in the availability of fish and fishery products, fuelwood, coastal protection, pollution abatement and carbon sequestration (FAO/GEF 2011).

According to available statistics (Njifonjou 1998), the 1,300 artisanal fishers operating around Limbe and Idenau (Cameroon estuary) land about 6,500 tons of fish worth CFAF 1.9 billion every year. This generates a monthly net income of CFAF 40,364 and 30,000 to the skipper and each crew member within a bottom gillnet fishing unit, on average, respectively. This compares with CFAF 102,000 to the boat owner and CFAF 30,000 to each of the two crew members, on average, within an artisanal fishing unit using surface gillnets (Mindjimba and Tiotsop 2012).

On the other hand, the 8,000 tons of oysters produced mainly by women around Mouanko, Mbiako and Yoyo I and II (Sanaga-Maritime division, Cameroon estuary) every year are valued at over CFAF 500 million (Ajonina et al., cited in MINEPDED 2012).

Regarding mangrove wood harvesting, the 200 woodcutters operating in the Cameroon estuary in 2001 to 2002 cut about 41,600 trees/yr or 208 trees per person on average. The resultant 30,000 m3 of fuelwood represent an annual turnover of CFAF 124.8 million or a monthly net income of CFAF 52,000 to 64,000 for each woodcutter on average (Din 2001; Tiotsop 2002). Artisanal fisheries operators are ranked first in terms of employment, production and turnover, followed by woodcutters. The other stakeholders have not been assessed in detail. Yet their impacts, as well as those of the foregoing on the mangrove, are far from negligible.

A number of frame surveys have been carried out along the coast to determine the size of the artisanal fisheries population (1987, 1995 and 2009), but very few systematic censuses of the entire population living in and around Cameroon’s mangroves have been conducted regularly. By some estimates (FAO/GEF 2011), the total population in the two main mangrove areas in 2010 stood at some 3,545 million people, or 99.6 percent of the entire population in the coastal area (17.7 percent of the country’s population of 20 million [UNFPA estimates]). Of this population, it is estimated that 268,000 people (representing 7.6 percent of the coastal population) live in mangrove areas. Although the Rio del Rey estuary has a smaller overall population (365,000) than the Cameroon estuary (3.18 million), relatively more people live in mangrove areas there (63 percent versus 1.2 percent, respectively).

Uncontrolled exploitation is undoubtedly the main issue faced by Cameroon’s mangroves, jeopardizing their long-term sustainability and that of the fisheries. In the past only fishers exploited the mangrove for their subsistence needs (fish smoking, fuelwood, boat making, etc.), whereas nowadays exploitation pressures have expanded to include commercial activities (logging, construction poles) and reclamation of vast mangrove areas for human settlements (urbanization, industrialization, port development, etc.). Reportedly, the first industrial exploitation of mangroves in sub-Saharan Africa started in the Cameroon estuary at Manoka in 1919 by a French company (Din 2001; Tiotsop 2002). Over 3,000 tons of mangrove wood were harvested within less than a decade and transformed into railway sleepers (the Trans-Cameroonian) and wooden barrels for the conservation of palm oil and table wine in Europe (Din 2001).

With the advent of the 1990s economic crisis, which notably led to salary cuts in the administration, drastic reduction of staff and laying off of numerous private-sector workers, trading of mangrove wood became a flourishing alternative activity; laid-off workers invested their last salaries in motorized chain saws, boats and even outboard motors (Din 2001; Tiotsop 2002). It is from this period that the anarchic and clandestine exploitation of the mangrove (particularly the mangrove forest) became more pronounced (Tiotsop 2002), making the trading of mangrove wood the activity which most threatens the mangrove.

The populations mostly affected are the artisanal fisherfolk. In addition to numerous invaluable goods and services, mangrove ecosystems provide crucial nursery habitats and spawning grounds for fish and many other aquatic animals. Their clearance therefore directly affects fisheries production and hence fisheries-dependent communities. In 2009 there were 32,624 operators along the value chain in the area representing 88.9 percent of the total fisherfolk along the entire coast (MINEPIA/MINADER 2009). They comprise fishers and crew members, fish traders and smokers, outboard motor mechanics, boat builders and other actors of various origins: Nigerians (78 percent), Cameroonians (14 percent), Beninese (4.3 percent), Ghanaians (3.7 percent) and Togolese (less than 0.1 percent).

Mangrove management is complex, sectoral conflicts are commonplace and there is no specific legal text governing the norms and standards for the use of mangrove resources or that could enable coherent action to solve inherent problems. Although the law on the environment has specifically identified mangroves as an ecosystem to be conserved, its implementation is restricted for want of enforcement text and ineffective monitoring of environmental impact assessment. Furthermore, the existing zoning plan does not encompass the southwest and littoral regions, thus sidelining the mangroves existing here (MINFOF 2012). Arguably, this makes an appropriate strategy and management plan for the mangrove backed up by effective control measures all the more essential.

It has been demonstrated (Ajonina and Usongo 2001; Din 2001; Tiotsop 2002, 2005) that the anarchic exploitation of mangrove wood for smoking fish in fishing camps and sale as fuelwood and construction poles in adjoining urban centers is the main stressor driving the degradation of this ecosystem. The dominant Rhizophora is the most commonly used species for these purposes. However, the findings of these studies, which primarily cover the Cameroon estuary, differ with regard to the rate of degradation of the mangrove. Din (2001) observed that 1,100 ha of mangrove were cleared every year to supply the city of Douala, compared to 231 ha found Tiotsop (2002) a year later. The difference may be due to the size of the sampled population in the two studies (120 and 10 informants, respectively). Ajonina and Usongo (2001) noted that about 140 ha of mangrove in the Douala-Edea Wildlife Reserve were cut every year, 99 percent of which was destined for smoking fish in nearby fishing camps (Yoyo I and II and Mbiako).

These studies show that mangrove areas located in the vicinity of urban centers are more stressed than mangroves located farther away. Therefore, the mangrove in the Rio del Rey estuary is less affected due to its remoteness, inaccessibility and lower urbanization compared with the Cameroon estuary. The estimated degradation of 1,100 ha/yr in the Cameroon estuary represents only 1 percent of the mangrove area, meaning it would take up to 100 years to deplete the entire mangrove in this estuary if no remedial action were taken.

Urbanization, port development and sand extraction also seriously affect the mangrove ecosystem. The extension of the Douala port, for instance, has led to the clearance of some 100 ha of mangrove (Din 2001), which is a relatively small area, representing less than 0.1 percent of the mangrove area in the Cameroon estuary. Pollution and eutrophication from direct and indirect discharge of liquid and solid effluents and aromatic hydrocarbons, excessive use of chemical fertilizers and non-biodegradable pesticides on agro-industrial plantations are additional stressors. These in turn contribute to mangrove degradation and biodiversity loss.

Human-induced impacts on the mangrove are well documented (Zogning 1993; Din 2001; Tiotsop 2002), and the major ones are (Figure 18.2) the depletion of the mangrove areas and biodiversity loss (including flora, aquatic and terrestrial fauna, mainly non-quantified except for the mangrove forest); the degradation of the mangrove for the extension of the Douala port or sand extraction; and the exposure of the coast to erosion and inundation with at times flooding of some fishing camps and pollution of the coastal area. There had been severe inundations in Douala and Limbe in 2000 and 2001 during which several people are reported to have died, especially in areas where the mangrove had been cleared, whereas some fishing camps in the Cameroon estuary had been abandoned due to flooding (Tiotsop 2002). Less inundation would therefore be expected and fewer people affected in areas where the mangrove had been conserved.

In the absence of reliable statistics, the steady decline in fish catches witnessed by artisanal fishers (Tiotsop 2002) is also a major concern resulting from the clearance of mangrove; this is coupled with a fall in fishers’ incomes, which in turn adversely affects their livelihoods.

Concerning governance, the overexploitation of fishery resources recorded in the coastal area prompted MINEPIA to prohibit the use of small mesh fishing gears as well as twin-trawling. MINFOF reinforced its control system in the field by creating new protected areas and intensifying control measures in existing ones. According to FAO/GEF (2011), the new protected areas include 20,000 ha of mangrove forests in the Ndongore National Park (covering 11.8 percent of the Rio del Rey estuary) and 20,500 ha in the Douala-Edea National Park adjoining the Douala-Edea Wildlife Reserve (covering 18.6 percent of the Cameroon estuary). MINFOF personnel in each park comprise a guard and a forestry agent, supported by staff from NGOs.

Human-induced degraded areas are globally characterized by the loss of the pristine vegetation of Rhizophora, which is replaced by few remnant shrubs and trees of low economic value, and the overall character of the vegetation and tree structure corresponds to a senescent formation (Din 2001) where swampy forest species progressively colonize the site. It has been observed (Din 2001) that Rhizophora spp. and Avicennia germinans re-colonize areas where the rocky substrate does not favor mangrove growth, whereas Nypa fruticans still grows normally in such areas. Some of these peculiar areas are found around Limbe. It is also noticed (Din 2001) that the number of species belonging to the genera Acrostichum, Avicennia, Conocarpus, Nypa, Laguncularia and Rhizophora has declined with the clearance of mangrove.

Mangrove density varies from 1,000 trees/ha in the old formations to 10,000 trees/ha in the young ones (MINEPDED 2012). Average standing volume is estimated at 1,537 m3/ha (2,350 trees/ha) in the Rio del Rey estuary and 1,335 m3/ha (2,000 trees/ha) in the Cameroon estuary. Mangrove trees in these two estuaries are morphologically tall, attaining heights of 50 m on average (Ajonina 2008), making them among the tallest in the world (Blasco et al. 1996). They are also among the largest and probably the best conserved in comparison with mangroves in Asia and West Africa, many of which have high degradation rates and have been completely depleted (Zogning 1993; Din 2001). In contrast with the practice in these countries, human activities such as aquaculture, rice cultivation, construction of salt pans and grazing, which can cause the depletion of mangroves on a large scale, are not yet practiced in Cameroon’s mangroves (Tiotsop 2002).

Artisanal fisheries are the mainstay and principal source of livelihood for coastal communities in mangrove areas. Fishing is generally practiced in the coastal area with motorized canoes, and in estuarine areas and creeks with non-motorized canoes. Fish is usually sold fresh in the fishing camps located in the vicinity of urban centers, or smoked in the farther camps. Fish smoking is controlled by women and provides a living for many coastal households (Njifonjou 1998; Tiotsop 2002). Annual nominal fish catch from artisanal marine fisheries along the entire coast is estimated at 93,000 tons (Mindjimba and Tiotsop 2012).

There are a number of other livelihood opportunities in the area, including:

Besides the previously mentioned ministries responsible for the management of mangroves at the national level, other influential bodies include regional and international organizations such as the Wild World Fund for Nature (WWF), the African Mangrove Network – which regroups civil society organizations and has several national centers, including the Cameroon Mangrove Network – and other development partners that provide technical and financial support for mangrove conservation through related programmes and projects.

Cameroon is a member of the following regional and sub-regional organizations: Central African Forests Commission (COMIFAC), Conference on Central African Rainforest Ecosystems (CEFDHAC) and Forestry Ecosystems in Central Africa (ECOFAC), among others. The country is also a signatory to relevant conventions: Ramsar Convention, Abidjan Convention for the Protection of Marine and Coastal Areas in Western and Central Africa, etc. Other international non-conventional instruments, such as the work plan of the International Tropical Timber Organisation (ITTO), also contribute to the mangrove conservation.

The long-term management of mangroves in Cameroon rests on a national strategy on sustainable management whose overall objective is to ensure sustainable conservation and use of this ecosystem such that it can optimally meet the needs of present and future generations at local, national and regional levels (MINEP/ENVIREP 2010).

To achieve this objective, the country has put in place an institutional, legal, regulatory and pragmatic framework, including a law governing environmental management and a law on the forestry, faunal and fisheries regime and its enforcement texts; it has also internalized international instruments such as the Principles for a Code of Conduct for the Management and Sustainable Use of Mangrove Ecosystems. As mentioned earlier, the multiplicity of institutions involved and their overlapping roles and inadequate coordination do not help in the implementation of these rules, regulations and instruments.

Many types of conflicts occur between the various actors in this ecosystem. The first one is the conflict between fishers and woodcutters from towns: the former complain that the latter destroy the mangrove. This results from the ignorance of the texts governing user rights in forestry and land tenure by these stakeholders (MINFOF 2012). Neither the forestry law of 1994 nor the strategy on the environment has identified the mangrove as a specific agro-geographical area.

The second type of conflict occurs between artisanal fishers and oil exploring and exploiting companies in the coastal area, particularly in the Rio del Rey estuary. In fact, some fishing grounds have been allocated to these companies, thus excluding any fishing activities in the area (MINFOF 2012).

Artisanal fishers also complain about the frequent encroachment of trawlers within the three-nautical-mile zone exclusively reserved for them by regulation. Such conflicts are compounded by Chinese vessels using twin-trawling (despite being prohibited by ministerial order of February 16, 2000) since their arrival in the area in the early 2000s. These conflicts usually lead to insecurity of fishers on the fishing grounds, destruction of their fishing gears and oftentimes deaths (Tiotsop 2002). Finally, also common are conflicts between artisanal fishers employing different fishing gear types and methods (e.g. those using drift nets and those using poles to set bottom gillnets).

Despite the short-term results from the reforestation of some areas in the Wouri estuary, it is apparent that the main issue we are concerned with is not adequately addressed because the degradation of the mangrove persists. According to MINFOF (2012), between 1980 and 2010, 20 percent to 25 percent of Cameroon’s mangrove areas had been depleted as a result of anthropogenic activities. Woodcutters continue to harvest mangrove forests with total impunity, marketplaces for associated products around Douala and Tiko are well known and coastal pollution by local industries continues unabated. This degradation trend is likely to continue if no remedial action is taken and the concerns of the resource users taken into consideration in the management and conservation processes.

Among the factors that hinder the achievement of the stated objectives in the short term are the ineffective organization of the riparian communities, the low involvement of these communities in the management of woody and fishery resources, the inadequate operational means among not only organized communities (those in Mouanko are a good example) but also public institutions charged with the management of mangrove and the complacency of certain forestry agents towards woodcutters from adjacent urban centers (no penalty is applied to them; on the contrary, forestry agents collect wood exploitation taxes).

Immigrant fishers have not adopted the improved fish smoking ovens developed by research, projects or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) with a view to minimizing the use of fuelwood; they are also reluctant to invest in durable infrastructure even if it is environmentally friendly. This annihilates de facto any other relevant initiatives, notably those related to reforestation.

Regarding institutional frameworks, the regulatory measures taken are poorly implemented, as are the relevant strategies and other measures aimed at addressing mangrove degradation. Moreover, relevant projects are not implemented, with some still at the design stage, or have already been designed but are awaiting implementation. Also, the fisheries bill tabled to the National Assembly since 2004 has yet to be passed.

Some of the main hindrances to the achievement of the long-term objectives are minimal environmental impact assessment for large investment projects or environmental audits for firms already operating in the area; ineffective monitoring for the implementation of existing environmental management plans; inter-sectoral conflicts of competence due to the multiplicity of institutions with overlapping roles, and in particular, the lack of coordination of actions and absence of strategic planning to guide development projects; inadequate national environmental and forestry policies for management of wetlands and fragile ecosystems; legal vacuum concerning land tenure; insufficient staff; ineffective surveillance system and equipment for control of fishing gears and methods; marginalization of issues pertaining to the management of mangrove compared to other developmental challenges; and non-compliance with the biological rest period in fragile and critical habitats.

Paramount among the factors causing the degradation of Cameroon’s mangroves is the lack of concern by competent authorities regarding the management of this ecosystem. This has led to anarchic exploitation, thereby threatening mangrove wood and fishery resources (Tiotsop 2002) with biological, ecological, socioe-conomic and cultural consequences. At present, the mangrove management plan and the relevant national regulations are inappropriate and unable to ensure proper mangrove conservation. This leads to illegal encroachment into this ecosystem. It is suggested that the management regime presenting maximum opportunities for enhancing economic growth without compromising long-term development options is the one based on sustainable management and use of the mangroves. To this end, it is imperative to address the threats identified in the present case study that hinder the conservation of this ecosystem.

This case study has highlighted the main cause of degradation of the mangrove, namely the ignorance of resource users and managers of the importance of this ecosystem. Thus there is a need to enhance their awareness of its importance. In particular, for coastal communities (composed mainly of fishers) for whom the mangrove forms part of the land tenure system, sustainable development options mainly involve awareness and environmental education on the contribution of mangrove particularly to fisheries production and protection of the coast against natural disasters. By adhering to the sustainable use of resources, the fishers would become the primary custodians of these resources vis-à-vis woodcutters from the towns, and this may also reduce the quantities of wood cut for minor needs (Din and Blasco 2003).

In parallel, it would be necessary to examine measures aimed at formalizing the extraction of wood and sand. To this effect, the identification of exploitable areas and implementation of an appropriate management and conservation system in these areas could be a possible solution. The development of an appropriate institutional framework for the management of this ecosystem and the adoption of an appropriate legal and regulatory framework constitute major strategic avenues for the sustainable management and use of Cameroon’s mangroves. Further investigation into the extent to which the destruction of mangroves affects the previously mentioned activities is also clearly warranted.

Finally, the government has recently drawn up a long-term national strategy for the sustainable management of mangroves, the overall objective of which is to ensure sustainable conservation and use of the resources for optimal contribution to meeting the needs of present and future generations at all levels and the national economy (MINEPDED 2012; MINFOF 2012). What remains, if the expected results were to be achieved, is to implement this strategy.

The authors hereby acknowledge the pertinent comments made by two anonymous reviewers. The incorporation of these comments has improved the quality of the chapter. The usual disclaimer applies.

Ajonina, G.N. and Usongo, L. (2001). Preliminary quantitative impact assessment of wood extraction on the mangroves of Douala-Edea Forest Reserve, Cameroon. Tropical Biodiversity 7(2–3): 137–149.

Ajonina, G.N. (2008). Inventory and modelling mangrove forest stand dynamics following different levels of wood exploitation pressures in the Douala-Edea Atlantic coast of Cameroon, Central Africa, Mitteilungen der Abteilungen für Forstliche Biometrie, Albert Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, February 2008, 215 p.

Banque Mondiale. (2004). Évaluation Environnementale du Programme de Relance des Activités Économiques et Sociales de la Casamance (PRAESC), Rapp. Final, Buursink International Consultants in Environmental Management. 124 p.

Blasco, F., Saenger, P. and Janodet, E. (1996). Mangroves as indicators of coastal change. Catena 27(3–4): 167–178.

Choudhury, J.K. (1997). Aménagement durable des forêts côtières de mangrove: développement et besoins sociaux. www.fao.org/forestry/fodal/wforcong/publi/v6/t386f/1-4.htm (accessed February 28, 2002).

Din, N. (2001). Mangroves du Cameroun: Statut écologique et perspectives de gestion durable, Thèse présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Docteur d’État ès Sciences, option écologie végétale, Université de Yaoundé I. 252 p.

Din, N. and Blasco, F. (2003). Gestion durable des mangroves sous pression démographique et paupérisation, Mémoire soumis au XIIe congrès forestier mondial, Québec city, Canada, [Online] www.fao.org/docrep/ARTICLE/WFC/XII/0394-B2.HTM (accessed March 24, 2015).

FAO. (1994). Mangrove forest management guidelines. Forestry Paper 117, FAO, Rome, 319 p.

FAO/GEF. (2011). Project document: Integrated management of mangrove ecosystems in the Republic of Cameroon. 84 pp.

Gabche, C.E. (1997). An appraisal of fisheries activities and evaluation of economic potentials of the fish trade in the Douala-Edea Reserve-Cameroon, Consultancy Report, Cameroon Wildlife Conservation Society, Yaoundé. 39 p.

Lafrance, S. and Myre, G. (1994). Pêche et environnement: document de sensibilisation, Centre spécialisé des pêches, Grande – Rivière, Québec. 38 p.

Mindjimba, K. and Tiotsop, F. (2012). Formulation de la seconde phase du Projet d’appui au développement de la pêche artisanale maritime et continentale (ADPAM). 101 p. (mimeo).

MINEP/ENVIREP. (2010). Études préliminaires de la deuxième phase du projet de Conservation et de Gestion participative des Écosystèmes de Mangrove au Cameroun, mangroves de Douala-Edéa et du sud, Rapp. Final. 125 p.

MINEPDED. (2012). Stratégie nationale de gestion durable des mangroves et des écosystèmes côtiers au Cameroun et son plan de mise en œuvre, Rapport prévalidé, Ministère de l’Environnement, de la Protection de la Nature et du Développement durable (MINEPDED). 111 p.

MINEPIA/MINADER. (2009). Enquête-cadre et étude socio-économique auprès des communautés de pêche de la façade maritime du Cameroun, Rapport définitif. 85 p.

MINFOF. (2012). Schéma Directeur d’Aménagement Participatif des Ecosystèmes de Mangroves et des Bassins Versants de la Zone Côtière de la Réserve de Faune de Douala-Edéa, Cameroun (Estuaire du Cameroun). 98 p.

Njifonjou, O. (1998). Dynamique de l’exploitation dans la pêche artisanale maritime des régions de Limbé et de Kribi au Cameroun, Thèse présentée à l’Université de Bretagne Occidentale pour l’obtention du titre de Docteur, École doctorale des sciences de la mer, Spécialité: Océanologie biologique, 339 p.

Tiotsop, F. (2002). L’importance des mangroves dans le système halieutique au Cameroun, M.Sc. en gestion des ressources maritimes, Université du Québec à Rimouski. x+88 p. (mimeo).

Tiotsop, F. (2005). Importance socio-économique des écosystèmes de mangroves dans les communautés côtières du Cameroun. Revue Congolaise des Transports et des Affaires maritimes 2: 51–75.

UNFPA. (2013). State of world population 2013: Motherhood in childhood: Facing the challenge of adolescent pregnancy, New York: UNFPA, p.116.

Zogning, A. (1993). Les mangroves du Cameroun. Conservation et utilisation rationnelle des forêts de mangrove de l’Amérique latine et de l’Afrique Vol. II, version française du rapport sur l’Afrique, ITTO/ISME Project PD114/90 (F): 189–207.