Onna Village, located on the west coast of mainland Okinawa (Figure 19.1), has a population of 10,838 people (as of 2015) and occupies an area of 50.77 km². The village used to subsist on agriculture and fisheries until a tourism boom arrived following Expo ’75 in Okinawa. With the emergence of tourism, conflicts arose between fisheries and this new industry, in particular related to marine water pollution caused by hotel construction and golf course maintenance, which negatively affected fishery species. Spatial conflicts on the water were the biggest concern from the mid-1970s to the late 1980s, due to a number of different uses which overlapped in the limited coastal area. The Fisheries Cooperative Association of Onna Village has been at the forefront of initiatives to address these problems and has attempted to lead the village through a period of rapid economic growth with a balanced use of the coastal area and its resources. Based on the I-ADApT framework (Bundy et al. 2016), this chapter first explains these large-scale changes and the mechanisms that generated them. Second, it illustrates the responses of society (Onna Village) to the issues and analyzes the reasons for success. Finally, it discusses several policy challenges in dealing with marine and global change.

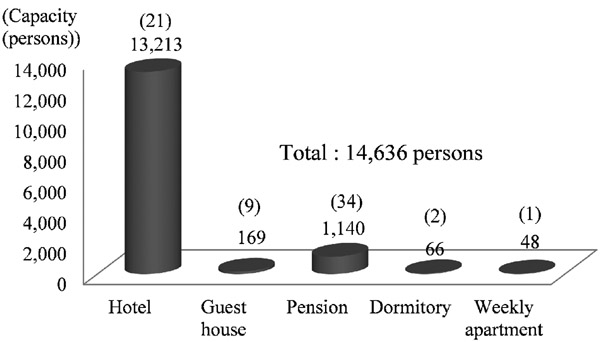

Following Expo ’75, which was held to commemorate Okinawa’s return to Japanese administration in 1975, Onna Village received an avalanche of tourists seeking to explore the rich natural environment of the local ocean and coral reefs. In 1973, prior to Expo ’75, there were only two accommodation facilities. However, by 2014 there were 79 accommodation facilities in Onna Village (Figure 19.2a), with a total capacity of 14,636 persons (Figure 19.2b). The hotel occupancy rate in Onna Village was 71.6 percent in 2012, according to data released by the Okinawa Development Finance Corporation (September 3, 2013). Considering that the hotel capacity was 11,794 persons per night in 2012 (Sightseeing Handbook of Okinawa 2012), this indicates that more than 3 million tourists visited the village in 2012. Such a large tourism boom caused inter-industry conflicts, including severe pollution of the marine environment and damage to fisheries, detailed in the following section.

Figure 19.2Tourism boom in Onna Village, Okinawa, Japan

a) Number of accommodation facilities in Onna Village; b) capacity in accommodation facilities by type in 2014. Number of facilities in each type is in parentheses; total capacity of each accommodation type is in bold. Source: Sightseeing Handbook of Okinawa (2014).

According to Okinawa Prefecture (Department of Environmental Affairs 2013) and the Eco Future Fund (2016), large-scale public construction and resort development projects have occurred continuously since Okinawa’s reversion to Japanese administration in 1972. Consequently, large quantities of red clay flowed into coral reef areas, causing considerable damage to the marine environment. In Onna Village, for example, where the beautiful coastline of coral reefs was an important tourist attraction after Expo ’75, a large amount of red clay flowed into rivers and sea areas as a result of resort construction, damaging the marine environment. Red clay refers to fine-grained soils, including the reddish-brown soil commonly seen in the Ryukyu Islands (e.g. Kunigami Merge and Shimajiri Merge), gray-colored soil (e.g. Jahgaru and Kucha, its parent material) and other soils (Okinawa Green Network 2015). When this red clay flows into the sea, it interferes with the growth of coral reefs by causing damage to them and the reef ecosystems and obstructing photosynthesis, which causes further damage to seaweed, fish and other marine life.

Table 19.1 shows measurements of red clay concentrations in bottom sediments in the coastal area from 1985 to 1990, at the height of the red clay runoff. Higher suspended particle in sea sediment (SPSS) concentrations are given higher ranks. The data illustrate that several coastal areas had ranks of 5 or more. Rank 5 is divided into 5a when the SPSS value is from 10kg/m3 to 30 kg/m3 and 5b when the SPSS value is from 30 kg/m3 to 50 kg/m3. Rank 5a is regarded as the SPSS upper limit rank for a vibrant coral reef (Omija 2003). For this reason, an area where the rank is 5a or more means severe red clay pollution. Note in particular that the highest value (1720 kg/m3) occurred in the Akase Coastal area near Onna Village. It had rank 8 and was the worst-affected coastal area.

Area |

Geographical feature |

SPSS(Suspended Particle in Sea Sediment) (kg/m3) |

Rank |

Date |

Inbu Beach |

Sea bed |

62.5 |

6 |

1986/9/3 |

Wetland |

24.8 |

5a |

1986/9/3 |

|

Other |

4.2 |

3 |

1986/9/3 |

|

Atutahara Coast |

Sea bed |

202 |

7 |

1990/8/22 |

Other |

2 |

3 |

1990/8/22 |

|

Akase Coast |

Sea bed |

1720 |

8 |

1989/4/18 |

Ota |

Sea bed |

31.5 |

5b |

1986/4/7 |

Other |

247 |

7 |

1985/11/11 |

|

Manza Resort |

Sea bed |

29.5 |

5a |

1986/9/16 |

Other |

0.9 |

2 |

1986/9/16 |

|

Onna Fishing Port |

Sea bed |

394 |

7 |

1990/4/1 |

Yakatakatabara |

Sea bed |

10.3 |

5a |

1986/4/9 |

Sea bed |

66 |

6 |

1989/4/7 |

|

Wetland |

271 |

7 |

1989/0703 |

|

Wetland |

113 |

6 |

1985/11/29 |

|

Nakadomari |

Wetland |

52 |

6 |

1985/11/29 |

Source: Okinawa Prefecture (1993)

Reference: Modified from “Department of Environmental Affairs (1993), 113pp”

Red clay outflows also inflict intolerable damage on fisheries. For instance, in addition to coral reefs being buried completely, fish disappeared, and ‘Mozuku’ seaweed (Cladosiphon okamuranus)/giant clam (Tridacna gigas) aquaculture was seriously damaged in 1989. Additionally, in 1990, 200 sheets of aquaculture nets (Asa seaweed [Ulva]) were damaged, and problems for ‘Mozuku’ seaweed aquaculture continued (Department of Environmental Affairs 1993). Natural factors including rainy weather, relatively high terrain such as mountains, lack of water-stable aggregates, highly dispersive soil and anthropogenic factors including hotel construction, golf course maintenance and agricultural land development were found to be the causes of red clay outflows. Red clay weathered by rainfall flows from the rivers into the sea, where it is spread and deposited on the seabed. When disturbed by tides or waves, it becomes resuspended and harms the marine environment (Okinawa Green Network 2015).

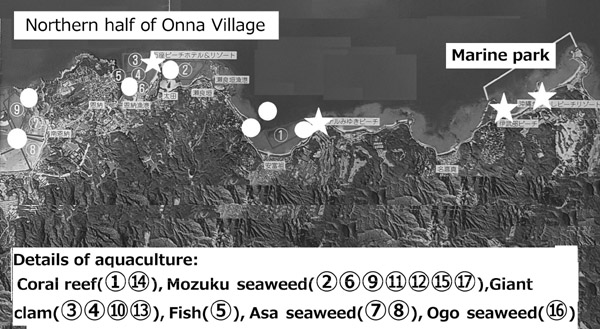

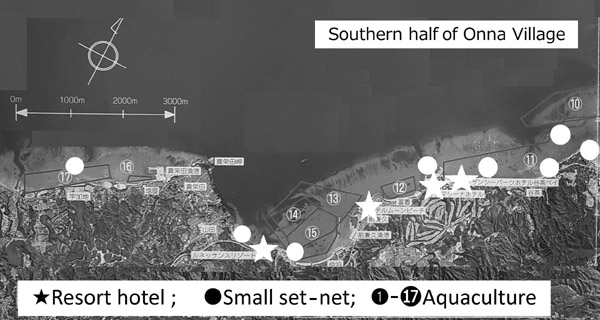

The tourism boom caused spatial conflicts between fisheries and the recreational marine industry. Figure 19.3 shows the coastal use in Onna Village. The types of coastal use are divided into four main groups: aquaculture, small set-net fisheries, marine parks and resort hotels. The types of aquaculture include the coral reef, ‘Mozuku’ seaweed, giant clam, fish, ‘Asa’ seaweed and ‘Ogo’ seaweed (Gracilaria asiatica). Against the backdrop of the tourism boom, the recreational marine industry, including resort hotel construction, diving and cruise ships, has grown at a fast pace, and a number of different uses have overlapped in the limited coastal area. As a result, there is a high incidence of conflict between industries. For instance, some hotels enclose part of the coastal area for their private use, or scuba divers enter into aquaculture areas without permission, eventually damaging fish species (Harada et al. 2009).

Figure 19.3 Types of coastal uses in Onna Village

Source: Modified from “Integrated coastal management council of Onna Village (2005), 4–5pp”.

To help deal with the problem, fishery operators who had long been burdened by this problem began by going into action. In 1980 they asked the village office to investigate the cause of red clay outflows, and in 1985 they demanded compensation for fishery damage due to red clay outflows. Additionally, the following year (1986) they had a huge sea protest against the exclusive use of the coastal area by the recreational marine industries. Taking the opportunity afforded by the initiative of the fishery operators, the village office, led by the mayor of the village at the time, facilitated the formation of various local rules for coastal use and conservation in Onna Village.

As Table 19.2 illustrates, these local rules fell into three major classifications: the prior consultation system (1985), co-existence and co-prosperity relationships (1986) and rules on coastal use and conservation (2005). First, the prior consultation system (1985) was introduced between the fisheries and the Onna Village Office. This meant that if there were no ‘red clay outflow’ prevention measures in place that had received prior approval by the fisheries association, there would be no development activities. Second, a co-existence and co-prosperity relationship (1986) was introduced among fisheries and tourism industries. Rules were specified for fishery development, chartering vessels, employment and coastal use. These included resort hotels providing a ‘Fishery Promotion Fund’ to fisheries, diving service operators chartering fishing vessels from fishermen, resort hotels putting a priority on hiring fishermen as crew members or as captains to operate vessels, fishers providing high-quality marine products at a reasonable price to hotels, tourism industries allowing free use of coastal areas, etc. (Lou 2013).

Local rules |

Contents |

Prior consultation system (1985) |

Introduced between fisheries and the Onna Village office. Agrees that if no ‘red clay outflow’ prevention measures are approved by the fisheries association and adopted in advance, there will be no development activities either. |

Co-existence, co-prosperity relationship (1986) |

Introduced among fisheries and tourism: • Resort hotel outlays ‘Fishery Promotion Fund’ to fisheries. • Diving service operators charter fishery vessels from fishermen. • Resort hotels put a priority on hiring fishermen as crew members or as captains when operating cruisers. • Fishery side provides high-quality aqua products at a reasonable price to the hotels. • Tourism side uses coastal area freely. |

Rules on coastal use and conservation (2005) |

Introduced by integrated coastal management council of Onna Village: • Rules prohibiting the harvest of fish, shellfish and seaweed, such as Asa seaweed, sea urchin, Mozuku seaweed, and giant clam. • Rules on preventing accidents in marine sports such as diving and jet skis. • Rules on conservation of coral reefs, spawning grounds of sea turtles, habitats of migratory birds, etc. |

Source: Reference: Lou (2013) and Harada et al. (2009)

Third, rules on coastal use and conservation (2005) were introduced by the integrated coastal management council of Onna Village (Integrated coastal management council of Onna Village 2005). These actions were part of the inquiry on the implementation of comprehensive governance of the oceans in open coastal seas conducted in 2005 by the National and Regional Planning Bureau of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. In making these new rules, the co-existence and co-prosperity relationship (1986) played a large part because of its prior formulation of local rules for the village. Examples include rules on prohibition on the harvest of fish, shellfish and seaweed, such as Asa seaweed, sea urchin (Echinoidea), Mozuku seaweed and giant clam; rules on preventing accidents in marine sports, such as diving and jet skis; and rules for the conservation of coral reefs, spawning grounds of sea turtles and habitats of migratory birds.

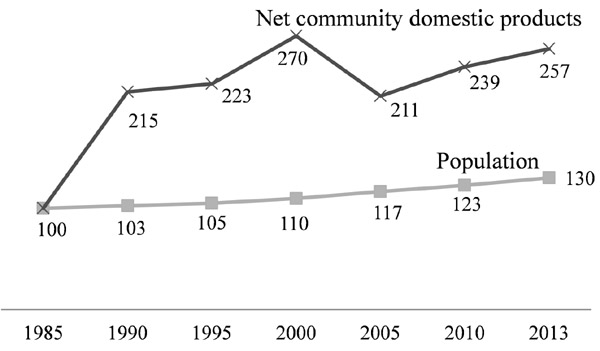

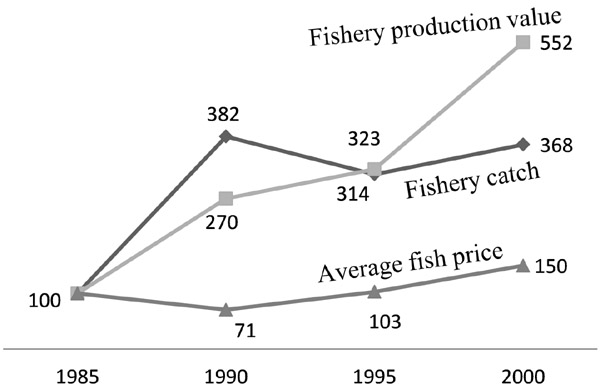

The results of this social response can be seen from the two aspects of economic impact and improvement of the marine environment. First, regarding economic impact, Figure 19.4 shows the trends in the population, net domestic product of the village (equivalent to the gross domestic product of Onna Village minus the depreciation cost of capital goods), fishery catch, fishery production value and average fish price index of Onna Village. The Okinawa Statistical Yearbook affirms that the net domestic products of Onna Village increased from 128.6 million yen in 1985 to 330.9 million yen in 2013. The village population also increased 1.3 times during these 28 years, which was contrary to the decreasing population trend and exodus from other rural areas of Japan (Figure 19.4a). Economic benefits can also be seen in the growth of fishery values. In particular, there has been a significant growth in fishery catch (3.6-fold), fishery production value (5.5-fold) and average fish price (1.5-fold) from 1985 to 2000 (Figure 19.4b).

The improvement of the marine environment is another example. The SPSS values of Akase Coast, which was severely polluted by red clay, are depicted in Figure 19.5. It can be seen that, despite the original high rank, the SPSS values generally declined throughout the 1990s in this worst-affected coastal area, which reached rank 5a with an SPSS value of 23.2 (kg/m3) in 2013. Additionally, the coverage by raw corals in Akase Coast, with a focus on the spectacular staghorn coral, increased from 1 percent around 1990 to 30 percent in 1996, and 50 percent or more in 1998 (Nakasone et al. 2000). The water quality has also greatly improved in all coastal areas of Onna Village, as can be seen from the great improvement of the severely contaminated Akase Coast so far (Figure 19.6). Note that three sites of the Akase Coast undergo monitoring every year, and this site has the highest SPSS value among the three sites.

Sources: Okinawa Statistical Yearbook (2013) and Onna Village Fisheries Cooperative (2001).

Figure 19.5 Trends in the extent of pollution in Akase Coast, Onna Village, Okinawa, Japan

Sources: Nakasone, et al. (2000) and Okinawa Prefecture (2013)

As described earlier, rates of economic performance and marine environmental quality have improved. This is a direct result of local rules and formation of mechanisms which ensure that the rules are followed effectively. The resulting restriction of unregulated acts of development and harmonious coastal use by various users translated into a significant contribution to mutual economic growth.

Several factors contributed to why this social response was successful. First, the new local rules acted as entry restrictions. As discussed earlier, the coastal environment and resource status of Onna Village are currently sound, meaning that various human activities that can have an influence on the coastal environment are conducted within the range of the environmental carrying capacity. Furthermore, local rules formed under agreements among stakeholders made this possible. For instance, placing restrictions on development activities based on mitigation of deleterious environmental results, such as requiring that red clay overflow prevention measures be approved in advance by the Fisheries Cooperative Associations and be in place prior to construction, and imposing a fishery promotion fund and chartering of fishing boats for recreational marine activities. With these, authorized users of the coastal areas are made clear, and the situation is transformed from a ‘global commons’, where the resources are available to everyone, to a ‘local commons’, in which access rights are limited to a given population, as described by the theory of the commons (Ostrom 1990).

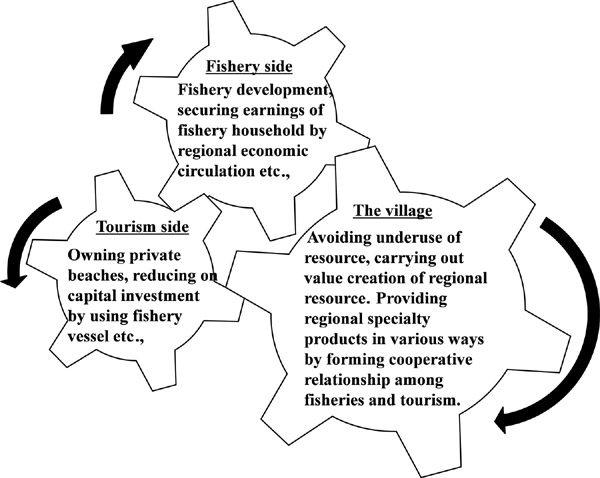

Second, behind the formation of these local rules, economic rationality among the various parties concerned can actually occur (Lou 2013). For instance, the merits include fishery promotion by the acquisition of the fishery promotion fund, fishery income security by regional economic circulation and avoidance of fishery operation problems for fishery operators. It also has possible merits, including improvement in the degree of freedom of coastal use such as private beaches, in human resources recruitment and in reduction of initial investment costs by using fishing vessels for tourism. Furthermore, these improvements benefit the village as a whole. For instance, the village can be spared the underutilization of local resources by avoiding problems and conflicts of coastal use, as well as the building of a collaborative relationship among various stakeholders and value creation of local resources (Figure 19.7).

Third, it includes initiatives of fishery operators in dealing with global change. There are several reasons why the efforts of fishery operators can help to achieve such a successful outcome. First, the fishing industry depends strongly on the natural environment. Next, organizations such as the Fisheries Cooperative Associations exist for fishery operators. A number of studies have accumulated which demonstrate how the Fisheries Cooperative Associations can help to provide effective resource management (Asano and Tanaka 2014). Organizational characteristics which help to explain why these associations are effective include their organizational structure, low inter-organizational conflict, appropriate decision making, guarantee of anticipated controllable profits, equitable distribution of profits, equitable cost sharing and leadership (Lou and Ono 2001). Finally, the association is not only for fisheries, but also for the promotion of the village as a whole because it has gained legitimacy as a local resource management organization.

Sources: Lou (2013) and Harada et al. (2009)

The story of Onna Village is a groundbreaking example of the resolution of marine environmental problems and conflicts between industries, which is now being used by Okinawa Prefecture to resolve similar issues elsewhere. What kind of social responses towards global change are desirable? Several policy challenges can be drawn here in conclusion. First, the formation of a structurally defined organization that can represent various stakeholders who use coastal resources is required. In this case, the ‘Coastal Waters Activity Coordination Board’, composed of various concerned parties, including fishery operators, recreational marine industries, resort hotel operators and the village office, was established. Consensus discussions within the board led to a series of local rules and a mechanism to ensure that these rules would be followed effectively. Second, functional factors, including the granting of economic incentives, formulation of rules following economic rationality and the granting of legitimacy, were needed for the organization to work effectively. In this case, these factors were absolutely imperative. Lastly, it goes without saying that the enhancement of capacity for such an organization by financial support, capacity building and education for this organization was essential. When these requirements are met, there is great promise for this story to be repeated in other areas.

The authors wish to express their sincere thanks to the FCA and the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Division of Onna Village for providing them with total cooperation in the progress of this research.

Asano, K. and Tanaka, M. (2014). Rural and urban sustainability governance, United Nations University Press, pp. 1–332.

Bundy, A., Chuenpagdee, R., Cooley, S.R., Defeo, O., Glaeser, B., Guillotreau, P., Isaacs, M., Mitsutaku, M. and Perry, R.I. (2016). A decision support tool for global change in marine systems. The IMBeR-ADApT framework. Fish and Fisheries 17: 1183–1193.

Department of Environmental Affairs, Okinawa prefecture. (1993). Report on red-clay pollution and the damages, pp. 1–204. (In Japanese)

Department of Environmental Affairs, Okinawa prefecture. (2013). Monitoring results on red-clay pollution area, pp. 1–386. (In Japanese)

Eco Future Fund HP. (2016). Activity report of forest prevention. www.eco-future.net/result/japan/okinawa/ (accessed July 2016).

Harada, S., Namikawa, T., Sinbo, T., Kinoshita, A. and Lou, X. (2009). Studies on multi use of coastal zone and the management rules – A case study of Onna Village, Okinawa Prefecture. Journal of Coastal Zone Studies 22(2): 13–26. (In Japanese)

Integrated coastal management council of ONNA Village. (2005). Rules on coastal use and conservation. www.vill.onna.okinawa.jp/Defaultf5fc.html (accessed July 2016).

Lou, X. (2013). The age of “Umigyo”- challenge towards fishery village’s revitalization. Rural Culture Association Japan 19 (rural revitalisation): 1–358. (In Japanese)

Lou, X. and Ono, S. (2001). Fisheries management of the Japanese Coastal fisheries and management organization. The Report of Tokyo University of Fisheries 36: 31–46. (In Japanese)

Nakasone, K., Omija, T., Mitsumoto, H., Uehara, M. and Oshiro, T. (2000). Monitoring water pollution caused by Reddish soil run-off. Journal of Okinawa Prefectural Institute of Health and Environment 34: 85–95. (In Japanese)

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 1–280.

Okinawa Green Network HP. (2015). http://okinawagreen.net/akatsuchi/index.html (accessed June 2015).

Okinawa prefecture. (2013). Basic Plan of Okinawa on Prevention Measures of Red-clay-outflow, pp. 1–65. (in Japanese)

Omija, T. (2003). Convenient measuring method of content of suspended particles in sea sediment. Journal of Okinawa Prefectural Institute of Health and Environment 37: 99–104. (In Japanese)

Onna Village Fisheries Cooperative. (2001). Statistical data from the 30th anniversary comemorable issue of the foundation of Onna Village Fisheries Cooperative, and the business report of Onna Village Fisheries Cooperative. (In Japanese)