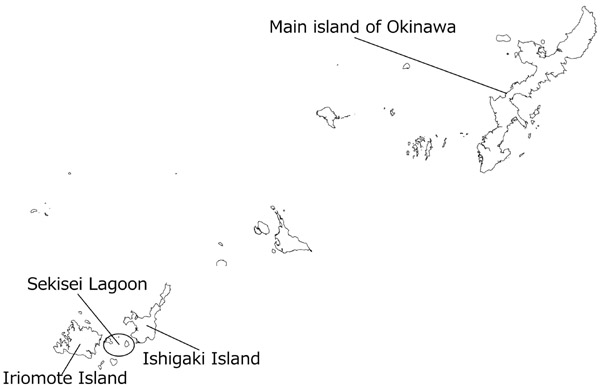

Coral reefs worldwide are under heavy pressure: 27 percent are permanently lost, and with current trends, a further 30 percent are at risk of being lost in the next 30 years. With such devastating levels of destruction, the social and economic implications for the millions of people who depend on coral reefs are of great concern (Cesar 2003). Consequently, the necessity of coral reef conservation and optimal management is urgent (Hughes et al. 2007; Olsson et al. 2008). Coral reef management by the ‘Sekisei Lagoon Nature Restoration Committee’ (SNC) is the focus of this chapter. The SNC aims to restore coral reef areas in the Sekisei Lagoon, located between Ishigaki Island and Iriomote Island in Okinawa, Japan (Figure 20.1). The goals of this chapter are to assess the background and conditions of the initiatives of the SNC to restore deteriorating coral reef resources and to discuss the institutional characteristic of the organization.

The SNC was established based on the Act for the Promotion of Nature Restoration enforced in January 2003. In 2009 a total of 20 nature restoration organizations were formed across the country, of which 3 (SNC, Takegashima Marine Park Nature Restoration Committee and Tatsukushi Nature Restoration Committee) were established with respect to the sea. All three are aimed at the restoration of coral communities, and the Sekisei Lagoon (SNC) is the largest marine area.

The value of coral reefs is diverse and includes ecological, genetic, environmental, cultural and marine leisure resource values together with social and economic development. The use of coral reef resources is also diversifying from use as a fishery resource and as sources of construction material in the past to use for marine environmental education or marine leisure (Beukering 2007). This diversification of uses and the expansion of human social activities are giving rise to the destruction and degradation of coral resources.

In Japan, coral reefs are legally positioned as a ‘common good’ as general fishery resources, and several legal limits are set with regard to their use. But, because they are a ‘common good’, coral reefs are predisposed to the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’ (Ostrom 1990). For that reason, there is a need to critically assess the management of coral reefs to avoid degradation. The analyses of what kinds of initiatives are being developed in SNC and if restoration committees are able to function as an effective management structure are needed.

Sekisei Lagoon extends across Iriomote Island and Ishigaki Island of Okinawa, in the southernmost prefecture of Japan (Figure 20.1). It extends about 20 kilometers from north to south and 30 kilometers from east to west, with depths of up to 20 meters. It supports a rich coral reef ecosystem, and 403 reef species have been confirmed throughout the area (Tsuchiya et al. 2004). This species richness is comparable to that of Philippine waters, one of the most diverse marine areas in the world (414 species) and exceeds the species richness (330 species) of the Great Barrier Reef (Tsuchiya 2010).

The Sekisei Lagoon “has the potential to be the source of coral larvae to the main island of Okinawa and plays a great role in supporting coral communities in Japan” (Tsuchiya 2010) due to the Kuroshio Current, which flows along the northern side of Sekisei Lagoon and then moves toward the north along the Pacific side of the Japanese archipelago.

However, the coral reefs of Sekisei Lagoon have been widely destroyed and have deteriorated over the last few decades. In a Ministry of the Environment (MOE) report on the Sekisei Lagoon (Japan Wildlife Research Center 2005), the history of the coral reef ecosystem of Sekisei Lagoon from the 1980s onward was analyzed (Figure 20.2).

According to a survey of the coral reef communities conducted in 1980, coral reef communities were distributed throughout the entire area of the Sekisei Lagoon (Japan Wildlife Research Center, 2005:5). However, since the beginning of the 1980s, there has been a population explosion of crown-of-thorns starfish, which prey upon coral reefs in Sekisei Lagoon, except those in the north of Kohama Island, where divers and fishing operators have been working to capture crown-of-thorns starfish. According to an investigation conducted by the MOE in 1991, “the coral reef area was reduced almost by half in 1991 by the occurrence of crown-of-thorns starfish” (Japan Wildlife Research Center 2005:6). The corals of the lagoon showed some recovery throughout the 1990s, but a distributional survey in 2002 indicated that the coral reef area was only 18 percent of the former area compared to around 1980 (Japan Wildlife Research Center 2005:7).

There was extensive coral bleaching caused by an increase in ocean temperature in 1998. Bleaching has been frequently observed over large areas of the region since then, and feeding damage caused by the outbreak of the crown-of-thorns starfish has also assumed serious proportions after 2000. Thus the corals of Sekisei Lagoon are facing threats from bleaching, predation and other factors, and coverage has decreased considerably since 1980.

Natural factors and anthropogenic factors can be cited as factors behind the degradation of coral reefs in Sekisei Lagoon (SNC 2007). Natural factors include the increase in ocean temperature leading to coral bleaching (Kamezaki and Ui 1984); typhoons leading to coral destruction; and abrupt increase in predators such as crown-of-thorns starfish (Kamezaki et al. 1987), operculate snails (Yokochi 2004) and fish causing damage to corals, although the abrupt increase in predators is often linked to anthropogenic causes. Anthropogenic factors include disease outbreak attributed to declining quality of water due to release of chemical substances and eutrophication due to human sewage, agricultural effluent (Nakano 2002, Hasegawa 2002 and Yamashiro 2004) red soil and sediment runoff; increasing tourist marine leisure use; coastal area utilization by traditional fishing businesses and the aquaculture industry; well-travelled sea-lane use by ferries and high-speed boats; land improvement projects for agricultural promotion and construction of hotels and inns for tourism promotion; poaching of corals by tourists and scuba divers; and coastal reclamation. Together these cause significant damage.

The city of Ishigaki and Taketomi Town in Okinawa Prefecture are the communities using the marine areas of Sekisei Lagoon (Figure 20.1). The livelihoods and production of these communities are founded on the rich coral reefs of the area. The three primary modes of use include fishery use, tourism use (including diving and underwater sightseeing boats) and transportation.

The ‘Business Report’ of the Yaeyama Fishery Cooperative reports that fishery operators have been declining since the 1980s, with a total of 322 local fishery operators in 2014 compared to 767 in 1988, 626 in 1993 and 503 in 2003. As a result of the collapse of the skipjack fishery, the leading fishery industry in the 1970s, overall fishery production in the region, including the lagoon area, was also severely diminished from 9,690 tons in 1974 to 2,574 tons in 2014.

In addition to the skipjack and tuna fishery on the high seas, the main gears used in fisheries around the lagoon include tuck-net, basket trap, gillnet, small size set-net and diving fisheries with lights. There is also aquaculture for the Japanese tiger prawn (Marsupenaeus japonicas) and Okinawa Mozuku seaweed (Cladosiphon okamuranus). With the collapse of offshore and deep-sea fisheries, the importance of coastal fishery in the lagoon is dramatically increasing.

Major fish species of the coastal fishery are reef fishes such as the Pacific yellowtail emperor (Lethrinus atkinsoni), sawtail (Prionurus scalprum Valenciennes), coral trout (Plectropomus leopardus), grouper (Epinephelinae), banana fish (Pterocaesio digramma), tridacna shells, squid (Teuthida) and octopus (Octopoda). In addition, local residents pick Asa seaweed (Ulva linnaeus) and Okinawa Mozuku seaweed and catch juvenile rabbitfish (Siganidae) for personal consumption.

The growing demand for leisure, the development of transport systems and the evolving demands of consumers have led to an increasing number of tourists since the 1980s and the region’s burgeoning tourism industry. According to the ‘Yaeyama Handbook of Okinawa Prefecture’, the number of tourists entering Ishigaki City reached more than 1 million in 2014, which represents a five-fold increase since 1975. Similarly, since 1975 the number of tourists arriving at Taketomi Town has increased 120-fold to 1.2 million people in 2014.

Rich natural resources and traditional culture represent important tourism resources in the region, with marine leisure use of coral reef areas becoming the region’s typical tourism activity (Lou 2013). The tourism services offered are mainly ecotours, using snorkeling, diving, sport fishing and canoes; coral reef tours using glass boats; and fishing-oriented tours that use traditional fishing boats such as the ‘Sabani’ (fishing boats used in the Ryukyu Islands since the early days). The number of diving operators using Sekisei Lagoon and surrounding waterways in 2009 numbered approximately 80 within Ishigaki City and 20 in Taketomi Town, thereby supporting the development of the regional economy.

Typical types of tourism-related pollution are the destruction of the corals during diving and snorkeling due to fin kicking, trampling and picking of corals, especially by beginners; the anchoring of diving and sport-fishing boats; and the contamination of the marine environment due to littering. Now with land development related to the construction of tourism/accommodation facilities on land, the load from the land, as typified by red soil runoff, also becomes bigger.

Marine transportation is linked with tourism. With the growing tourism industry and the consequent economic expansion, ferries, high-speed boats and sightseeing boats increasingly commute between the islands. The general movement pattern of tourists visiting this region is to cross Ishigaki Island from Okinawa or Honshu via airplanes or cruise ships, high-speed boats and ferries departing from Ishigaki Port and then to tour Taketomi Island, Iriomote Island and other remote islands via Sekisei Lagoon.

According to statistics compiled by Ishigaki City, the number of ships entering Ishigaki Port increased from around 20,000 in 1988, when Ishigaki Port was developed, to 51,000 in 2005. Cargo throughput has also been swelling, with imports superseding exports. Demand for the transport of goods has been growing every year. The combined total number of passengers who embark/disembark from ships going to Ishigaki Port stood at around 10,000 people in 1980 and reached 2.06 million in 2005. Furthermore, according to the ‘Transport Handbook’ of the Okinawa General Bureau, the number of sailings of high-speed boats and other vessels that tour the neighboring remote islands dramatically jumped to 964,000 in 2005 from 200,000 recorded in 1995. The rise in transport volume in the lagoon necessitated the dredging of new channels and further development, which resulted in the increased pollutant load to the sea.

The following two measures may be seen as examples of conventional formal systems. More specifically, the first one has to do with the setting of legally regulated areas, and the other concerns the usage regulations pursuant to the Fisheries Adjustment Regulations of Okinawa Prefecture. These formal regulations apply not only to Sekisei Lagoon, but also to the wider marine area.

There are three legally regulated areas comprising a) marine park zones according to the Natural Parks Act, b) special marine zones with a protected natural environment according to the Nature Conservation Act and c) protected waters according to the Act on the Protection of Fisheries Resources.

The marine park zone is designated for the purpose of preserving the natural landscape at sea in accordance with the Natural Parks Act, and in this designated area, acts such as the capture of designated animals and plants, coastal reclamation and the modification of the shape of the seabed are regulated. Sekisei Lagoon was designated as the Iriomote National Park (name changed to Iriomote-Ishigaki National Park in 2007), and then in 1977, four marine park zones 213.5 ha (2.135 km2) in area, about 1.6 percent of the 13,000 ha (130 km2) total area of the coral colony of Sekisei Lagoon, were designated. However, fishery species in these designated areas are excluded from the capture regulations, so it cannot be expected that the marine ecosystem will be adequately protected. Furthermore, the primary objective of the Natural Parks Act is the preservation of the landscape of national parks, so it is not very effective in the maintenance of the ecosystem itself.

The special marine zones that protect the natural environment aim to designate and protect marine areas in accordance with the Nature Conservation Act. Similar to the marine park zones, the capture of designated animals and plants, coastal reclamation and the modification of the shape of the seabed are strictly regulated. But unlike the marine park zones, these special zones basically aim to keep the excellent nature of these areas in their current state. The Sakiyama Bay (128 ha, 1.28 km2) has been designated among the marine areas adjacent to Sekisei Lagoon.

The waters with fishery resource protection have been set in a bid to protect and multiply the number of aquatic plants and animals that have been markedly dwindling in abundance and to take rigid conservation measures such as banning fishing and prohibiting reclamation and other modification acts in accordance with the Act on the Protection of Fisheries Resources. Two protected waters have been set around Ishigaki Island. However, the waters with aquatic resource protection aim at protecting individual aquatic species, but not technically protecting coral reefs in their entirety, so it could not be expected to effectively restore the deteriorating coral reefs.

According to the Fisheries Adjustment Regulations of Okinawa Prefecture, there are four capture regulations that aim to protect fishery resources: a) setting of fishing ban periods, b) size of fish caught, c) special catch permits and d) rules on reef breakage within the fishing zones. Even the regulations based on the Fisheries Adjustment Regulations pertained to the use of fishery resources and were not effective rules for solving problems regarding the deterioration of coral reefs which has affected Sekisei Lagoon since the 1980s.

The MOE took on a substantial leadership role in a bid to restore and conserve the Sekisei Lagoon ecosystem and established the SNC as an implementing body pursuant to the Act for the Promotion of Nature Restoration. The latter was enforced in January 2003, in light of the policy direction made under the ‘New National Biodiversity Strategy’ formulated in March 2002 by MOE, which indicates that the reinforcement of ecosystem conservation, sustainable use and the restoration of nature ought to be tackled. The act, which laid down the fundamental principles and procedures of nature restoration, was positioned as a cross-cutting law for the comprehensive promotion of policies related to nature restoration. The ‘Basic Plan for Natural Restoration’ was adopted at a Cabinet meeting in April of that year and brought out detailed measures.

Nature restoration is

the conservation, restoration, generation and control of the natural environment with the participation of the related administrative institutions, relevant local government units, local residents, specified non-profit organizations (hereinafter referred to as ‘NPOs’), experts and various other local units toward the restoration of the ecosystem and other natural environments that were lost in the past.

(MOE 2008)

The MOE defined five fundamental principles for nature restoration, namely, a) securing biodiversity, b) participation and partnership of diverse groups in the region, c) implementation based on scientific knowledge, d) adaptive procedures and e) promotion of learning about the natural environment.

To achieve these principles, each region is taking the following measures in accordance with the ‘Basic Nature Restoration Plan’ formulated by the government. First, it will be based on requests of the implementers (administrative institutions, NPOs). As of June 2007, the percentage of calls from the country’s ministries and agencies stood at 22 percent, whereas those of regular public organizations came to 39 percent, NPOs at 18 percent, private groups at 18 percent and scholars at 3 percent. Second, the calls at the first step lead to the launch of the ‘Nature Restoration Committee’. Third, overall concepts are made through consultative meetings. Fourth, the committee formulates the ‘Implementation Plan for the Nature Restoration Project’ based on the overall concept, and this plan is sent to the state ministers in charge and the governors and then approved by the state ministers. Fifth, implementers of nature restoration projects will be selected according to the approved implementation plan. Sixth, the implemented project is monitored, and the results of assessment will be fed back and then reflected in the implementation of restoration (Figure 20.3).

As a result of the implementation of the Act for the Promotion of Nature Restoration, the ‘Sekisei Lagoon Nature Restoration Master Plan’ was formulated in July 2005 in collaboration with the relevant organizations, with the MOE playing a central role. Comprehensive initiatives that integrate the management of terrestrial and marine areas are necessary to restore the nature of Sekisei Lagoon, and it was advocated that it is important for local residents, administrative agencies, various local groups and coral reef ecosystem specialists to share information and cooperate based on this common understanding. To that end, the MOE, the Cabinet Office and Okinawa Prefecture became implementers based on the act. In particular, they called on stakeholders such as fishers, farmers, scuba diving service operators, NPOs and academic experts and by holding a series of meetings with them, finally established the SNC in February 2006.

According to the ‘1st SNC Proceedings’, by agreeing to the call of the implementers, there were 64 participating SNC committee members at first (24 individuals, 19 groups/companies, 15 local public agencies and 6 national government representatives). The SNC bylaws were approved at the inaugural meeting, and various matters concerning, for example, the name, purpose, target area, affairs under jurisdiction, composition of committee members, selection of chairman and vice-chairman, establishment of subcommittees, establishment of secretariat and operation were discussed. Members are elected with the approval of the committee based on public invitation and original member recommendations, and the number of members continued to increase after the initial meeting, with 108 members as of February 2013.

The secretariat of the SNC is the Naha Nature Conservation Office, Kyushu Regional Environment Office, MOE and Port Planning Division, Development Construction Department, Okinawa General Bureau and Cabinet Office, and the Naha Nature Conservation Office is in charge. There are five subsidiary organizations, established in 2012 based on the bylaws of the committee: the task force on livelihood and utilization, fund steering committee, land area measures working group, marine area measures working group and public awareness working group. Furthermore, the committee drew up the ‘Sekisei Lagoon Nature Restoration Overall Plan’ in July 2007 after holding five meetings based on the Act for the Promotion of Nature Restoration and formulated the ‘Implementation Plan for the Sekisei Lagoon Nature Restoration Project’ during the seventh meeting held in March 2008. After this consultation process, a basic policy for the restoration of the nature of Sekisei Lagoon was developed.

First, the Sekisei Lagoon Nature Restoration has long- and short-term goals: the long-term goals are “to realize a healthy interaction between man and nature and to restore the rich coral reef ecosystem that existed at the time of park designation in 1972” to be accomplished in 30 years; the short-term goal is “to eliminate the negative environmental impacts on corals to stop further degradation” to be accomplished in 10 years.

Second, there are ten main principles of the Sekisei Lagoon Nature Restoration: comprehensive approach, use of natural regeneration, scientific recognition, precautionary principle, simultaneous pursuit of local industries and natural regeneration, adaptive management, implementation of continuing and feasible initiatives, collaboration by various organizations and individuals, information publication and sharing and environmental education.

By incorporating these main principles, 22 points of the following six items have been established as initiatives to be developed for nature restoration: (i) removal of threatening factors (response to feeding damage by crown-of-thorns starfish and disease, red soil runoff prevention measures, drainage measures, promotion of fishery resource management, improvement of tourism methods, lifestyle improvement, measures against marine litter, measures against abnormal weather); (ii) creation of a favorable environment (restoration of coral reef ecosystems, restoration of coastal ecosystems, establishment of eco-friendly structures); (iii) promotion of sustainable resource use (promotion of proper use, designation of protected habitats); (iv) communication, education and public awareness (promotion of understanding regarding coral reef ecosystem, improvement of awareness in related industries and livelihood, establishment of tourism which leads to improvement of tourists’ consciousness); (v) research and monitoring (understanding and monitoring of coral reef ecosystem health, sociological survey) and (vi) continuation of efforts (promotion and support of activities by private sector, project assessment, publicity of initiatives) (SNC 2007).

Based on the previous information, the following points can be extracted as the methodical features of the organization of SNC. First, even though MOE played a large role at the beginning of the SNC’s establishment, the SNC’s initiative has avoided the conventional administrative method of a top-down approach from national to prefectural or municipal governments, and currently the projects are promoted based on a system incorporating bottom-up decision making, which respects ideas and suggestions from rural areas. Second, local autonomy and independence are respected, and originality and ingenuity are valued. Third, government participation and cooperation across the government are emphasized, with an eye toward the “implementation of comprehensive measures” with cooperation across the government. More specifically, SNC pursues the “utilization of the system of various projects” composed of national and local governments, NPOs and various funds. Fourth, the participation of diverse entities and roles of the members are clarified. For instance, members of the committee go through formalities of approval from the committee in principle, but it is premised on free participation by public invitation. Fifth, the SNC aims at unanimous consensus formation (in the formulation of basic concepts) through in-depth discussions. To that end, for instance, the SNC decides on weekend meetings, observer participation, complete information disclosure and provision, publication of meeting rules, establishment of subcommittees for hearing a wide spectrum of opinions and occasional collection of feedback on the contents of project execution and committee operations. Sixth, the SNC places emphasis on scientific knowledge, with many researchers participating as committee members.

As seen, the committee aims at adaptable management. It manages a highly steady and open network in terms of organizational principles and is trying to enforce governance based on co-management as an organizational principle. Co-management, which encourages active participation of citizens and stakeholders, is set to be the basic principle of the committee, while it breaks through inefficient sectionalism-oriented management and sets cross-sectional administrative participation and initiatives as its basic stance. Functionally, the SNC puts emphasis on an adaptive management method, based on a Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle and a preventive principle.

However, at this point the ten-year-old committee has already held 18 meetings and seven years have passed since the implementation plan was formulated; assessments on how its initiatives are implemented and how it pays off are needed. It would be important to determine how features of the institutional design of the committee identified earlier work in real life or how various administrative and organizational issues like leadership and authority, duty and responsibility, budget and cost, enforcement and penalty, and incentive and motivation are cleared in actual initiatives.

The first question is whether participation of citizens and stakeholders is achieved. In this case, participation in SNC – in other words, being a member of the SNC – is the participation mechanism for citizens and stakeholders. Since the number of SNC members increased to 114 in 2015 from 84 when SNC was first established, citizen participation has been developed. In addition, there are 39 individual members and 41 group members in the committee (as of 2015), showing active participation by various stakeholders.

However, the participation of citizens and stakeholders is on a voluntary basis; therefore, those who applied for membership at the beginning stage were all approved without any procedure, and those who applied afterwards were approved by a clap of hands in the annual meeting. The latter style became a customary process of the committee since then. No applicant to become a member of the SNC has been refused up to now.

Excellent co-management seems to be achieved by free participation in the committee, but it makes decision making difficult for the committee because the legitimacy of a committee member can be called into question. There is no guarantee of whether respective members have enough representation to reflect citizens’ and stakeholders’ opinions. Consequently, when selection of difficult management methods and management rules are demanded, the legitimacy of decision making of the committee itself is likely to be called into question.

The second question is about whether there is horizontal cooperation among administrative sections. There are 27 sections and organizations from the local government and 7 sections and organizations from the central government present in the SNC, and it seems the entire administrative organization related to Sekisei Lagoon is participating. Respective sections are supposed to take part in one of the following lower branches of SNC, including a task force section, fund organization section and four working groups. As seen, formally, the committee is designed to perform cross-sectional cooperation in terms of management. However, in actuality, some working groups are still working on the projects from conventional vertically divided administration, and because the working group members are not fixed, not many substantial discussions have been conducted in annual meetings due to lack of consistency and continuity.

As described earlier, though the SNC is a co-management–oriented organization institutionally designed to satisfy certain requirements, it could not be said that it is performing according to substantial principles of co-management, and therefore further discussions on the desirable way to achieve stakeholder participation and administrative cooperation are needed.

Beukering, V.P. et al. (2007). The economic value of Guam’s coral reefs. University of Guam Marine Laboratory Technical Report No. 116.

Cesar, H., Burke, L. and Pet-Soede, L. (2003). The economics of worldwide coral reef degradation, Cesar Environmental Economics Consulting (CEEC), 6828GH Arnhem, The Netherlands, 23 p.

Hasegawa, H. (2002). Environmental damages of coral island area due to land reforming projects, WWF Japan Annual Report 2001: 18–33. (in Japanese)

Hughes, T.P., Gunderson, L.H., Folke, C., Baird, A.H., Bellwood, D., Berkes, F., et al. (2007). Adaptive management of the Great Barrier Reef and the Grand Canyon world heritage areas. Ambio 36(7): 586–592.

Japan Wildlife Research Center. (2005). Sekisei Lagoon Nature Restoration Master Plan, Ishigaki Ranger Office, Naha Nature Conservation Office, Ministry of the Environment, 1–82 pp (in Japanese). http://sekiseisyouko.com/szn/pdf/7-1.pdf (accessed April 2016).

Kamezaki, N. and Ui, S. (1984). Bleaching of hermatypic corals in Yaeyama Islands. Marine Parks Journal 61: 10–13. (in Japanese)

Kamezaki, N., Nomura, K. and Ui, S. (1987). Population Dynamics of stony corals and Acanthaster plance in Sekisei Lagoon, Okinawa (1983–1986). Marine Parks Journal 74: 12–17. (in Japanese).

Lou, X. (2013). The era of Umigyo: Local challenges toward reactivating fishing villages. Rural Culture Association Japan, 1–358 pp. (in Japanese)

MOE. (2008). Nature restoration projects in Japan towards living in harmony with the natural environment, 1–24 pp. (in Japanese). www.env.go.jp/nature/saisei/tebiki/pdf/all.pdf (accessed April 2016).

Nakano, Y. (2002). A review of physiological and ecological researches on responses of hermatypic corals by environment impacts. Coral Reef Research in Japan I, Japanese Coral Reef Society, 43–49 pp. (in Japanese)

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1–280 pp.

Olsson, P., Folke, C. and Hughes, T.P. (2008). Navigating the transition to ecosystem-based management of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 105: 9489–9494.

SNC. (2007). Sekisei Lagoon Nature Restoration Overall Plan, Ministry of the Environment, 1–83 pp. (in Japanese). www.env.go.jp/nature/saisei/law-saisei/sekisei/sekisei0_full.pdf (accessed April 2016).

Tsuchiya, M. (2010). Restoring coral reefs: An introduction from the Sekisei Lagoon nature restoration project. Environmental Research, 158 p. (in Japanese)

Tsuchiya, M., et al. (2004). Coral reefs of Japan, Ministry of the Environment and Japanese Coral Reef Society. (in Japanese)

Yamashiro, H. (2004). Coral diseases. Coral Reefs of Japan, 58–61 pp. (in Japanese)

Yokochi, H. (2004). Predation damage to corals. Coral Reefs of Japan, 51–57 pp. (in Japanese)