A HO-CHUNK PHOTOGRAPHER LOOKS AT CHARLES VAN SCHAICK

Tom Jones

AS A MEMBER OF THE HO-CHUNK NATION and a photographer, I am honored to be part of this collaboration on Charles Van Schaick’s photographs of the Ho-Chunk. This essay draws on visual records from the Charles Van Schaick collection housed at the Wisconsin Historical Society, combined with the oral histories of our elders. As I studied these photographs and shared them with family and tribal members, I discovered stories I had never known before. I began to understand that these photographs come with history, stories, and lives I could not fully know or experience. Even though I am culturally connected to the people represented in these photographs, I was uncertain at the outset whether I would be able to read these images truthfully or adeptly. Each photograph and each person comes with their own life history, and I was reading these photographs with twenty-first-century eyes. In the process of selecting images for the book, questions began to arise about viewership, my own and that of the general public: How do our ancestors shape our identities? When do we have to adapt our culture or our lives in order to survive? Is the physical home as important as the psychological home? How do non-Ho-Chunk perceive these photographs? To what extent does the viewer place falsehoods or misconceived histories onto an image?

When I look into the faces of the people within these photographs, I find that looking back are the faces of individual Ho-Chunk I see today. Anthropologists and historians who study and photograph particular ethnic groups have often used the word “typical,” as in “a typical Ho-Chunk.” This ethnographic code for describing a people as a tribe cannot be applied to the Ho-Chunk, because our history, like many American Indian peoples’ histories, is so complex. As I showed the photographs to tribe members, many said, “That person looks like this family or that family.” When a Ho-Chunk looks at these photographs, we distinguish each family differently. One has to understand that people came into the tribe in many different ways. There were raids, intermarriages with other tribes or with non-Indians, and rapes of our women by United States soldiers during the forced Indian removals. My grandfather, Jim Funmaker, who was born in 1904 and lived to be 100 years old, shared with me that members of other tribes were adopted as Ho-Chunk. As a result, each family looks different. So, what is a “typical” Ho-Chunk? This cannot be answered visually, but I believe it can be answered culturally.

There is an unstated complexity in the way a photograph is read by individuals from different cultures and backgrounds. Each time a photograph is encountered, the viewer will decipher the image with constructed imagination or constructed knowledge. There are also the intentions of the photographer and subject. What has the photographer decided to show us and what has the sitter decided to reveal? I believe that in the end, Van Schaick’s studio portraits become more about the sitter than the photographer or viewer. To understand the photographs more fully, it is our task as viewers to add the historical contexts back in. Whether we read these photographs through the lens of tribal history or through family stories, the interpretation we place on the image today comes from our understanding of what the people in the photographs have experienced.

Without stories or history, the photographs in this collection have little meaning. Take the copy photograph that Van Schaick made from an unknown photographer for the sitters, Henry Thunder and my great-grandfather George Funmaker Sr. Both men look directly at the camera, each firmly positioned for the long camera exposure. Henry holds a traditional pipe, while my great-grandfather nonchalantly holds a cigar. A Ho-Chunk finger-woven sash is draped over his shoulders. The two young men exhibit a casual comfort with the camera. Both wear a mixture of Ho-Chunk and Western clothing. Their long earrings graze their suitcoats. The viewer who takes this photograph at face value might think, “Look at the visual contrast of traditional and contemporary.” In reality, only ten years before, my great-grandfather was ice-skating on a pond when the United States soldiers rounded him up at gunpoint along with the rest of his village. He was twelve at the time. In the dead of winter, they herded them onto railroad boxcars to be sent west in one of the last forced Ho-Chunk removals in the 1870s. When they were relocated they were allowed to bring only what they could carry. Many families were separated, the villages were burned, and sacred objects were lost. Numerous Ho-Chunk lost their lives along the way. I marvel at the casualness of this image and the visual power that the two men evoke. Is this only because I bring the stories that I have heard to the photograph?

Henry Thunder (WahQuaHoPinKah), left, and George Funmaker Sr. (WojhTchawHeRayKah), ca. 1888.

What the photographs in this collection cannot convey are the hardships and struggles of the removals of the Ho-Chunk, especially during the removal period of the 1830s to the 1870s. For many years my ancestors lived as refugees in Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Nebraska. Each time they were deprived of food and warmth. As many as eight hundred people died of starvation during these journeys. The Ho-Chunk were removed from their homeland at least eleven times over the course of more than forty years by the United States government. Dissatisfied with the conditions of the land in which they were placed, they returned again and again to their original territory. They would travel at night and hide during the day. I asked my mother, Jo Ann Jones, why our people continued to return to Wisconsin. Her reply was, “My father told me that the Great Spirit placed us here and we were to take care of our ways of life here.”

When viewing these photographs one has to imagine the period of the 1870s, when many groups of Ho-Chunk returned to Wisconsin for the last time on foot, horseback, or canoe from Nebraska. They eventually settled in sixteen counties throughout Wisconsin where we originally resided. Around 1880, Charles Van Schaick began photographing the Ho-Chunk in Black River Falls as part of his work as a studio photographer. He continued until the early 1940s. By that time, Ho-Chunk were returning to the Nebraska reservation in cars to visit relatives and tribal members from whom they had been physically separated years before.

Despite the terrible history of the removals and the poor treatment of Native peoples by the U.S. government, Van Schaick’s photography of the Ho-Chunk is not exploitative or intrusive. He worked as a commercial photographer and the Ho-Chunk were his clients. Photographers who were his contemporaries took different approaches when photographing the Indian; Edward Curtis used his photographs to depict what he saw as a vanishing race, and H. H. Bennett to promote tourism in the Wisconsin Dells. The photographs Van Schaick produced of the Ho-Chunk who settled in and around Black River Falls were not used as a commodity to be distributed to the public. The Ho-Chunk commissioned these postcard photographs for their homes and to be given as gifts to family and friends. They were shared with family members in Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota, and Nebraska. Van Schaick would often make multiples of the photographs so family members could come to his studio and buy them at a later date.

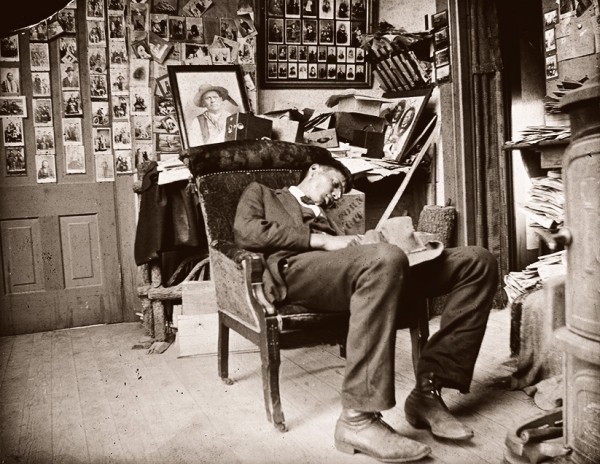

A man sleeping in a chair, possibly Thomas Thunder (HoonkHaGaKah). On the back wall of Van Schaick’s studio are photographs he made available for purchase.

Because Van Schaick’s photographs of Ho-Chunk were for personal rather than public consumption, their worth is unique. The Ho-Chunk were not visual props for the photographer. The Ho-Chunk presented themselves to the camera the way they wanted to be seen, often, especially in earlier years, in traditional Ho-Chunk regalia. In terms of technique, Van Schaick preferred to photograph his clients in a full-body style—from head to toe, rather than a head portrait or half-frame. He rarely did any type of close-up on the Ho-Chunk until later years. It is likely Van Schaick’s Ho-Chunk clients wanted to show their complete outfits. In later years, as Ho-Chunk began to wear Western clothing, Van Schaick employed a close-up style that he was already using with white subjects. In the majority of photographs, early and late, the Ho-Chunk sitter looks directly at the viewer. The sitter is not stoically looking off in the distance as seen in the work of many of Van Schaick’s contemporaries. This direct view is consistent with the way Van Schaick photographed white subjects and may simply have been Van Schaick’s style for taking portraits (see below).

To the viewer with no cultural background in Ho-Chunk history, the stories behind the photographs are not easily accessible. Such stories give the background necessary to understand particular images. In an interview with Flora Thundercloud Funmaker Bearheart conducted by Frances Perry, the Black River Falls librarian and the town’s unofficial historian, Flora tells a story from her mother, Annie Blowsnake Thundercloud’s youth. Annie came to the studio to have her picture taken wearing the new appliqué dress she had sewn for herself (see page 44). The photograph was not what she expected. Moments before it was taken, her mother draped several necklaces of white bugles and shells around Annie’s neck. They completely covered the fine handwork of her appliqué. As viewers, would we ever be able to discern this in her expression? Further, would we guess that the picture was taken to send to relatives and friends in other settlements to notify eligible young men about her looks and her eligibility as a future wife?

An unidentified white man and woman.

Susie Kingswan (HeNuKah) and her son Fred Kingswan (MaHeNoGinKah), ca. 1894.

When I looked closely at another photograph of a group of beautifully dressed Ho-Chunk, I recognized a few of these people as members of the medicine lodge (see page 51). I was not sure why the seated woman, Lucy Emerson Brown, had the markings on her cheeks that are worn when a new member joins the medicine lodge. An elder, Delphine Swallow, explained to me that Lucy was trying to be pretty. This was the Ho-Chunk interpretation of white women wearing rouge, and it can be seen in other photographs of the time (see page 160). Amy Lonetree, whose great-great-grandfather, Alex Lonetree, stands directly behind Lucy, related another story about this image to me. Many non-Ho-Chunk would ask, “What kind of shirt is he wearing?” and “Is it traditional?” In fact, Alex was in downtown Black River Falls and saw the jester-like shirt in the store window. He liked the shirt and bought it.

Van Schaick did not limit his work to studio photography. Outside the studio, his photographs act as snapshots. They lose the formality of the studio and become loose and carefree. Starting around 1895, he used the 4 × 5 glass plate negative camera like a brownie camera; although it was not compact, it was mobile, and didn’t require the long exposure times of the studio. With this camera Van Schaick chronicled what happened in real time at powwows, in home settings, and on the streets of Black River Falls (see pages 105, 124, and 129). He was not staging a romantic ideal of what was, or intruding where he was not welcome; like other whites, he was a spectator at powwows, which were not closed to outsiders. The Ho-Chunk were his neighbors, his fellow townspeople with whom he interacted outside the studio. His outdoor environmental photography shows us the everyday, the celebrations, the harvest, the sick, the homes, the religious, and the ceremonial.

On the surface it may seem that going to where one’s subjects live is more authentic than having them come to the studio. Is this really so? Do our preconceptions play a part? Take the image of the home compared to the portrait in the studio (see pages 122 and 171). Some individuals who came to Van Schaick’s studio to be photographed in their finery were living in canvas-covered tents or ciiporoke. Does this knowledge affect the viewer’s interpretation? In a newspaper article for the Chicago Daily Tribune on December 22, 1931, Rev. Ben Stucki of Neillsville gives us a glimpse into the Ho-Chunk culture. He writes,

The Indian knows no social inequality. A man is a man whether he is dressed in rags or beautiful robes, and the Indian always shares his food with those less fortunate. The Indian feels that all he has belongs to the Great Spirit and that it was sent for the needs of all. Indians are naturally honest and there is no thievery among them. They lock their tents by laying a stick in front of the door and no Indian would think of entering a tent marked in that way.

“In the forty years we lived with the Winnebagos in Jackson county,” states Rev. Stucki, “Nothing was stolen from our home by the Indians, but I cannot say as much for the White people.” An example of locking their ciiporoke in order to let people know they were not home can be seen in the image of a board leaning near the door (see page 124). My grandfather, Jim Funmaker, who was born near Trempeleau, Wisconsin, lived in a traditional ciiporoke with his family.

When my grandfather was ninety-eight years old, my mother asked him who his friends were when he was young. His reply was, “I didn’t have any friends.” Because our elders are constantly joking I thought he was too, so I laughed. He paused and then continued to say that his father, George Funmaker Sr., kept his family and children away from others during times of sickness. Tuberculosis and influenza were going around at this time. It was a few years before my grandfather’s birth in 1904 that smallpox was brought into the tribe again. These diseases killed many people within the tribe and also some of the individuals who are represented in these photographs.

Van Schaick’s photographs preserve this difficult time in our history. When he photographed the smallpox epidemic of 1901, what was his original intent? Who was the audience for these images? Seeing the heartbreaking photographs of the children with smallpox was painful for me. I wanted to look away, but at the same time I also wanted it burned into my memory in order to never forget a disastrous part of our history. This is a tragic story that I have heard countless times, passed down from our elders, about the devastation of diseases like smallpox and influenza on the tribe’s population. One of the earlier smallpox epidemics was purposely introduced through contaminated blankets from the United States government as a means of wiping out Native populations.

During the 1901 outbreak, government officials conjectured that Indians from Nebraska had brought the disease to Black River Falls. In a letter dated September 2, 1901, to Wisconsin Attorney General E. R. Hicks, State Board of Health Secretary Dr. U.O.B. Wingate requested that the Ho-Chunk pay for the expenses of his mandated quarantine by deducting the costs from their monthly allotment money.

George Funmaker Sr. (WojhTchawHeRayKah) is surrounded by his three youngest sons, ca. 1915. Standing left to right are George Funmaker Jr. (HoonkMeNukKah), Harold Jones (WaNaChaySheNaSheKah), and James (Jim) Funmaker (HaHayMonEKah).

These photographs, and that letter, are evidence of a devastating time in Ho-Chunk and American history and should never be silenced. It is through the photographs that we have been given a concrete image of this human suffering. Here is a visual record of why so many families were extinguished. Do these images affect a Native American differently than they would a non-Indian? These horrific images place a new burden on all viewers of these photographs to learn more about the history of the American Indian and the devastating policies enacted by the American government.

Two unidentified young Ho-Chunk girls with smallpox are kneeling outside their lodge. Some of the Ho-Chunk suffering from smallpox were quarantined during the 1901 outbreak.

An unidentified young Ho-Chunk boy and girl with smallpox stand outside of their home.

It is important that there be no silencing of history or censoring of photographic images that Ho-Chunk and non-Ho-Chunk do not want to be seen. They are a part of our lives, our truths, and our history. Another burden of our history that can be seen in these photographs is the drinking of alcohol. A common photographic convention during Van Schaick’s career was for sitters to be photographed with a glass or bottle of alcohol. These bottles were props that Van Schaick furnished for his sitters. A liquor bottle, shot glasses, and a round carafe can be seen in photographs of both white and Ho-Chunk sitters (see page 206). Here is a case that is ripe for censorship. Alcoholism is an issue that many Indians do not want to confront, but these photographs document this issue and should not be ignored. When we view these photographs we maybe able to laugh it off, but it is important to not turn away from this destructive problem.

One of Van Schaick’s most iconic images of the Ho-Chunk is a photograph of two seated Ho-Chunk women, laughing with one’s arm wrapped around the other’s shoulder and their hands slightly raised. The viewer with an untrained eye is often drawn to this image because the women are joking, animated, and smiling. A closer look reveals that part of the photo has been retouched: in the women’s hands, etched out, is the shape of a whiskey bottle. Who etched the bottle out? Was it Van Schaick, or one of his assistants? Was it etched out at a later date? Who decided to censor the evidence of alcohol, and why? Could it have been at the request of the sitters themselves?

Is the evidence of alcohol in the image a means of coping or are the Ho-Chunk in these images acting out in a humorous fashion? It is the Ho-Chunk humor that I believe has helped us cope with the tragedies we face and have faced as a people. The span of Van Schaick’s career coincided with the turbulent transition in Ho-Chunk culture from being able to freely hunt for food to feed one’s family to needing a permit to hunt or needing to rely on the government relief office for food. Decisions about permits and relief were often made on a whim by relief workers, who could take an individual’s drivers’ license or car keys away. Only then would they offer relief. As I read the Banner Journal articles of Ho-Chunk journalist Charles Low Cloud for inspiration, I came across this writing, “Shoes Don’t Grow,” from November 22, 1939, by a young girl that sums up the relationship with the government relief office and our Ho-Chunk humor (see page 209). Doris (Dolly) Stacy writes, “One day a mother went up to the relief lady and said, ‘May I have some shoes for my girl?’ The relief lady answered, ‘I think not, as you had a big garden last summer.’ The mother answered, ‘But I did not grow shoes in the garden.’”

Three unidentified white men dressed in bib overalls holding cigarettes and beer bottles, ca. 1900.

Clara St. Cyr, a Nebraska Winnebago, left, and Lucy Davis (NukZeeKah), the sister of John Davis (KaRoJoSepSkaKah), ca. 1900.

This Ho-Chunk humor does not always come through within the photographs of Van Schaick, but there are glimpses, such as Frisk Cloud riding a cow during a gathering for a powwow, or the quirky image of the man with an apple in his mouth.

Many visual codes make these images specifically Ho-Chunk. Take the example of a group of men standing outside at a powwow (see page 113). Standing shoulder to shoulder, each of the men holds what appears to be a walking stick. In actuality, this lets other Ho-Chunk know that these men are from the Bear clan, whose responsibility it is to police the people and keep order within the tribe. Another example is the man wrapped in a blanket leading a horse during winter. The man, who is identified as David Good-village, is shown in the process of moving his camp in order to hunt and trap at the Mississippi River near Marshland, Wisconsin. It was common for Ho-Chunk to have summer and winter camps during this period. One was for farming and the other for hunting and trapping. The horse carries on its back the cattail reed mats that would be used to cover David’s home; snowshoes hang from the other side.

Throughout the history of photography the photographic image has simulated cultures, but there are times when members of a distinct culture also use photography to their own advantage. Does Van Schaick’s photography show the evolution of culture or does it contribute to the misconception of culture? Visual cues can be misleading if we do not know the context. For instance, the dominant stereotype of the Indian man with long hair is rarely visible in these photographs. This was not the hairstyle of Ho-Chunk men during the time period that Van Schaick photographed. Only a few examples of long hair exist in the collection. These are men who traveled the world as performers in Wild West shows (see page 110). They were Indians playing Indian for the general public. Who perpetuated this myth? The Ho-Chunk who participated or the whites who attended the performances?

Frisk Cloud (MauhHeTaChaEKah) riding a cow at a powwow, ca. 1905. Watching Frisk, left to right, are two unidentified men, likely Ho-Chunk, Albert Thunder (CheNunkEToKaRaKah), George Monegar (EwaOnaGinKah), Andrew Bigsoldier (WaConChaShootchKah), and an unidentified white man.

An unidentified man, seated with his family, with an apple in his mouth.

Ironically, Wild West shows did influence Ho-Chunk dress. The Plains Indian war bonnet was introduced at the turn of the nineteenth century, during Wild West shows in which many Ho-Chunk participated. Though it was used initially only when performing, it has become a part of the Ho-Chunk culture that continues today, a visual marker of those who have warrior or chief status. Thomas Thunder, pictured in full regalia with an elaborate war bonnet, was a powwow organizer and performer in Wisconsin Dells (see page 85). Benjamin Raymond Thundercloud was photographed in similar clothing in 1912 (see page 45). Traditionally, an eagle feather on a stick also signifies warrior status, as in the portrait of Civil War veteran John Johnson (see page 100). Today we see eagle staffs that are elaborate, with many feathers.

David Goodvillage (WauHeTonChoEKah) with his horse loaded with supplies, including cattail mats, snowshoes, and canvases, for a hunting and trapping trip at Marshland near the Mississippi River.

Taken over a sixty-year span, these photographs show the visual evolution of Ho-Chunk culture. Van Schaick does not create a static fiction like Edward Curtis, who constructed his photographs in order to create a visual record and a way of life before white contact. Ours is not a stagnant culture. The Ho-Chunk were adapting to, not assimilating to, societal changes, just like any other persons of this time. Do we ask the German farmer why he no longer uses a horse and plow to till the earth? Why, then, does contemporary culture question the shift to modern dress and modern textiles? Originally, buckskin was the material used to make clothing, but with the introduction of European trade cloth, Ho-Chunk women adapted to this more readily available textile. While each woman has her own variation in style or design, they keep the basic design in this transformed traditional woman’s dress (hįnųkwaje). The Ho-Chunk women in these photographs continued to hold hard to their traditional dress style, just as Ho-Chunk women continue to do today, in turn keeping the Ho-Chunk heritage alive while adapting to the current culture.

The studio and environmental portraits created by Charles Van Schaick in collaboration with the Ho-Chunk are a valuable archive of a people. They do much to dispel the popular myth of a “typical Ho-Chunk.” The Ho-Chunk came to the studio in control of how they wanted to be represented. Through these incredible photographs they preserved and passed on their identity as a people and a way of life. For me, the photographs have become a reminder and a memorial of a people who had a strength, determination, and resilience to survive and fight for their people, their land, and their culture.