“AMONG THE [HO-CHUNK] INDIANS there has been a systematic teaching of courage from infancy to the grave,” wrote Henry Roe Cloud in the early twentieth century. “The old-time Indian had respect for the aged, developed art, and had a love for the beautiful. He developed thrift. He was always willing to work. We [as Ho-Chunk warriors] have all inherited these characteristics.”1 The words of Henry Roe Cloud hold true today. Even after the United States government removed the Ho-Chunk and other tribes to reservations and disrupted their traditional cultural practices, the Ho-Chunk maintained most of their warrior traditions and continue to hold their veterans in high esteem.

The Ho-Chunk have participated in many of the United States’ wars. During the War of 1812 they sided with the British against the United States, and during the Civil War they fought for the Union. Seventy-two Ho-Chunk warriors joined the Omaha Scouts and saw action during the Civil War, patrolling the Indian frontier west of the Mississippi. Some individual Ho-Chunk fought with other units, including John Hazen Hill, who enlisted with the 14th Cavalry in Kansas, and John Greencloud “Green Thunder,” who served in the army as a scout with the Comanches (see pages 97 and 98).

After the Civil War, the opportunity for Ho-Chunk to fight as warriors was limited, but they still maintained many of their traditional warrior practices. Warrior songs were handed down, and many of the clans still held war bundle feasts, as some still do today. When the United States entered into World War I in 1917, the opportunity for Ho-Chunk to become warriors and receive the honor and privileges associated with warrior status resulted in a large number of Ho-Chunk enlisting.

To ensure the warriors’ success, each clan gave the warriors items from their war bundles to carry with them as they left for service. Many World War I veterans returned with trophies to show proof of their bravery. When the warriors returned home, victory dances were held and the veterans were honored in the warrior tradition. The Ho-Chunk again had warriors to carry on the traditions and tell their stories at wakes. New warrior songs were composed to add to the traditional repertoire, including songs for each branch of the military in which Ho-Chunk served. Today there are Ho-Chunk veterans from every branch of the armed services.

The warrior tradition was given new life after World War I and in the wars that followed, from World War II through the current conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Today, the Ho-Chunk warrior tradition remains a vital part of the Ho-Chunk way of life—a fact evident to anyone attending the annual Ho-Chunk Memorial weekend powwow in Black River Falls, which pays honor to all veterans, Ho-Chunk and non-Ho-Chunk.

Civil War veteran James Bird (WeeJukeKah or MaKeSucheKaw), ca. 1900. The emblem on his hat is made of two crossed arrows, the insignia of a Civil War Indian scout. James Bird was a private with Company A of the Omaha Scouts, a Civil War outfit consisting of six white officers and seventy-two Ho-Chunk soldiers.

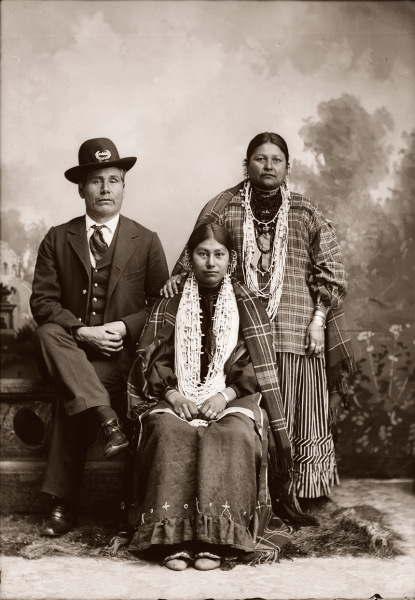

Non-Ho-Chunk Charlie Saunders with his Ho-Chunk wife, Mary Eagle (ChaUkShePaRooEWinKah), and her daughter, Annie Davis Bigsoldier White Rogue (KeeReeJayWinKah), ca. 1900. Saunders served in the Civil War as a private in Company B of the 1st Wisconsin Cavalry and was twice a prisoner of war. The first time, he was captured in Bloomfield, Missouri, and released in exchange for a Confederate prisoner. He was captured again on July 30, 1864, and held at the infamous Andersonville Prison. Saunders is wearing the GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) emblem on his hat. Saunders spoke the Ho-Chunk language and was close to the Ho-Chunk community, but it is not known whether he received Ho-Chunk warrior privileges.

Homer Snake wears a hat with a GAR emblem, signifying he is a Civil War veteran, ca. 1900. Snake served as a private with Company A of the Omaha Scouts.

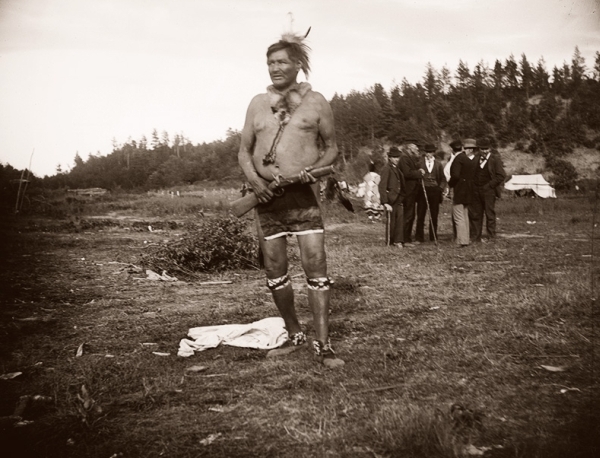

Henry Rice Hill (SanJanMonEKah), ca. 1900. Henry was a private in Company A of the Omaha Scouts during the Civil War. He is wearing a beaded choker around his neck and two Ho-Chunk bandolier bags across his chest, and he holds a pipe tomahawk. The golden eagle tail feather in his hat signifies warrior or veteran status.

John Hazen Hill (XeTeNiShaRaKah), ca. 1910, served in the Civil War as a scout leader with the 14th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry Regiment.

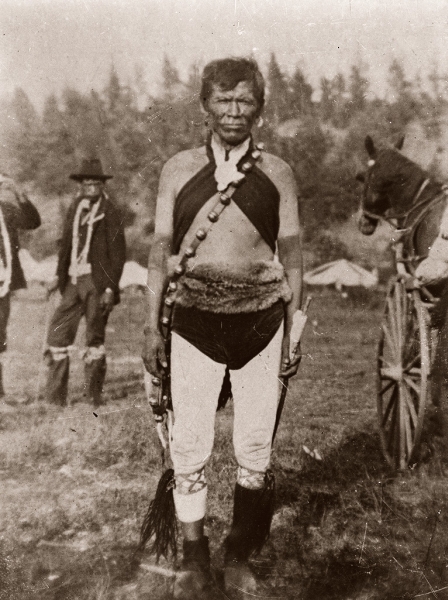

John Greencloud “Green Thunder” (WauKonChawChoKah), ca. 1906. John served in the Civil War as a scout for the U.S. Army with the Comanches.

Army veteran George Standingwater (HaNaKah), ca. 1906.

John Mike Jr. (HayShooKeekah), rear left, pictured with his family, ca. 1901. Standing from left to right are daughters Ada Mike (HunkEWinKah), Lizzie Mike (WeHunKah), and Belle (Mattie) Mike (ENooKah). Wife Kate Mike (ENooKeeKah) is seated with son Dewey Mike (WaHoPinNeKeKah) in her lap. Dewey Mike, who became an army private, was killed in action on August 30, 1918, in France. A member of Company A, 128th Infantry, he was among the twelve thousand Native Americans on active duty during World War I. At the time, most Native Americans were not United States citizens and were not granted citizenship until the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. Dewey was honored posthumously in May of 1933 when his mother visited his grave in France. Kate Mike was the only Native American Gold Star Mother to be invited by the government to France. She made the trip despite her limited ability to speak English, laying a wreath of pine boughs from the trees Dewey played beneath when he was a boy on his grave.

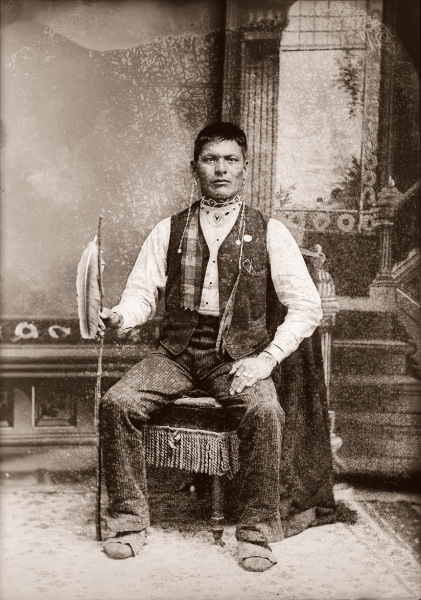

John Johnson, ca. 1885. John was a private with Company A of the Omaha Scouts. He is wearing traditional Ho-Chunk moccasins and earrings. In his hand is a staff with an eagle feather attached, indicating his warrior status.

World War II veteran Ruby Whiterabbit is wearing an eagle feather war bonnet (mąąšų wookąnąk). The war bonnet was not traditional among the Ho-Chunk but came to them from the Sioux (Lakota), with whom the Ho-Chunk participated in Wild West shows. The eagle feather bonnet is only worn by chiefs and warriors among the Ho-Chunk.