In this chapter, I provide information that you should have about over-the-counter (OTC), herbal, alternative, and vitamin products before giving them to your children. Although OTC drug products are generally regarded as safe to use without a physician’s approval or prescription, they continue to have potential for serious adverse effects or toxicity if not given correctly. Herbal and alternative products, which are not well regulated and are heavily marketed, may not produce the benefits for your child that manufacturers would like you to believe.

Parents often give OTC medicines to infants and children, most commonly acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) to treat fever. Because OTC medicines are, by definition, available without a prescription, it is not necessary to speak with a pharmacist or pediatrician before administering them. Getting advice from your pharmacist or pediatrician would certainly be helpful, however, because administration of OTC medicines can result in adverse effects, some potentially serious. Published studies have shown that parents easily make mistakes when giving OTC products to their children. Some OTC medicines, although marketed and available as pediatric products, are best not given to children.

The use of herbal products, alternative medicines, and vitamin products in adults and children has increased in recent years. Unlike prescription and OTC medicines, herbal and vitamin products and alternative medicines are not stringently regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This lack of regulation has significant implications for their potential safe use and raises questions about their effectiveness.

OTC medicines are regulated by the FDA using different methods than those used to regulate prescription medicines, and this difference has important implications for their safety and efficacy in pediatrics. Prescription medicines undergo extensive animal and human testing—actual use studies—prior to entering the commercial marketplace and becoming available for prescribing by physicians. Actual use testing is not required for OTC drug products. Instead, the active ingredients contained in OTC drug products are regulated by drug “monographs.” Drug monographs are developed for therapeutic categories of medicines, such as the category of medicines for pain (acetaminophen, ibuprofen).

In 1972, the FDA began one of its most extensive projects, referred to as the OTC Drug Review, by evaluating the safety and efficacy of all active ingredients in these therapeutic categories. This process is ongoing and has not yet been completed. It is estimated that more than 100,000 OTC products are available today, with approximately several hundred different active ingredients contained in these products. Product active ingredients are grouped into more than 80 different therapeutic categories. OTC drug products containing active ingredients determined to be unsafe or ineffective during the Drug Review process have been removed from the marketplace and are no longer available.

How do these regulatory differences between OTC and prescription medicines relate to pediatrics? And what are the implications for giving OTC medicines to your child? For one thing, dose recommendations for children listed on most OTC drug products have been developed by extrapolation of adult doses, which involves reducing doses by percentages based on an adult’s weight (for example, 25 percent of an adult drug dose for a child who weighs 25 percent of what an adult weighs). We now know that this method is not accurate and does not reflect the numerous differences between an infant or child’s body as compared to an adult’s body. This is well illustrated by the use of OTC cough and cold drug products in infants and children (see chapter 1 and below for more about this) and their potential dangers. Thus, although OTC drug products are generally regarded as safe enough to use for self-diagnosis and self-treatment by adults (meaning that a physician’s prescription is not needed), their use in the pediatric population may not be as similarly safe and effective.

Over the past five years the instructions for using OTC liquid drug products for children have improved, and consequently these medications are easier to use. In 2011 the FDA published specific guidelines for pharmaceutical manufacturers of OTC liquid drug products. The national trade organization representing OTC drug product manufacturers, the Consumer Healthcare Products Association, released similar recommendations at about the same time. Prior to the publication of these guidelines, an important study was published in the pediatric medical literature in 2010. Researchers in this study evaluated 200 top-selling pediatric liquid OTC drug products and concluded that the vast majority of them contained numerous types of confusing and problematic dosing directions that could easily lead parents to make dosing errors when administering the medications to their children. These potentially problematic dosing directions included, for example, lack of inclusion of a dosing device with the product, inconsistent and confusing dosing directions, and markings on differing parts of the product and packaging, among others.

After release of guidelines by the FDA and industry trade group, another study published by different researchers evaluated pediatric OTC liquid drug products in a similar manner. These researchers concluded that most products had improved and were largely adhering to these guidelines. However, some products were not sufficiently improved, and the potential for parents to easily make mistakes when using them remained. For example, some pediatric OTC liquid drug products may still be using “teaspoonful” or “tablespoonful” as the measurement in dosing directions.

In 2015, the American Academy of Pediatrics and several other major medical organizations recommended that liquid medicines not be dosed with “teaspoonful” or “tablespoonful” measurement directions, and that mL (milliliter) be used instead (see chapter 2 for more information on dosing). Although many OTC liquid drug products are now less likely to be administered incorrectly, the potential remains. As a parent, you should be aware of the possibility of dosing errors with OTC liquid products.

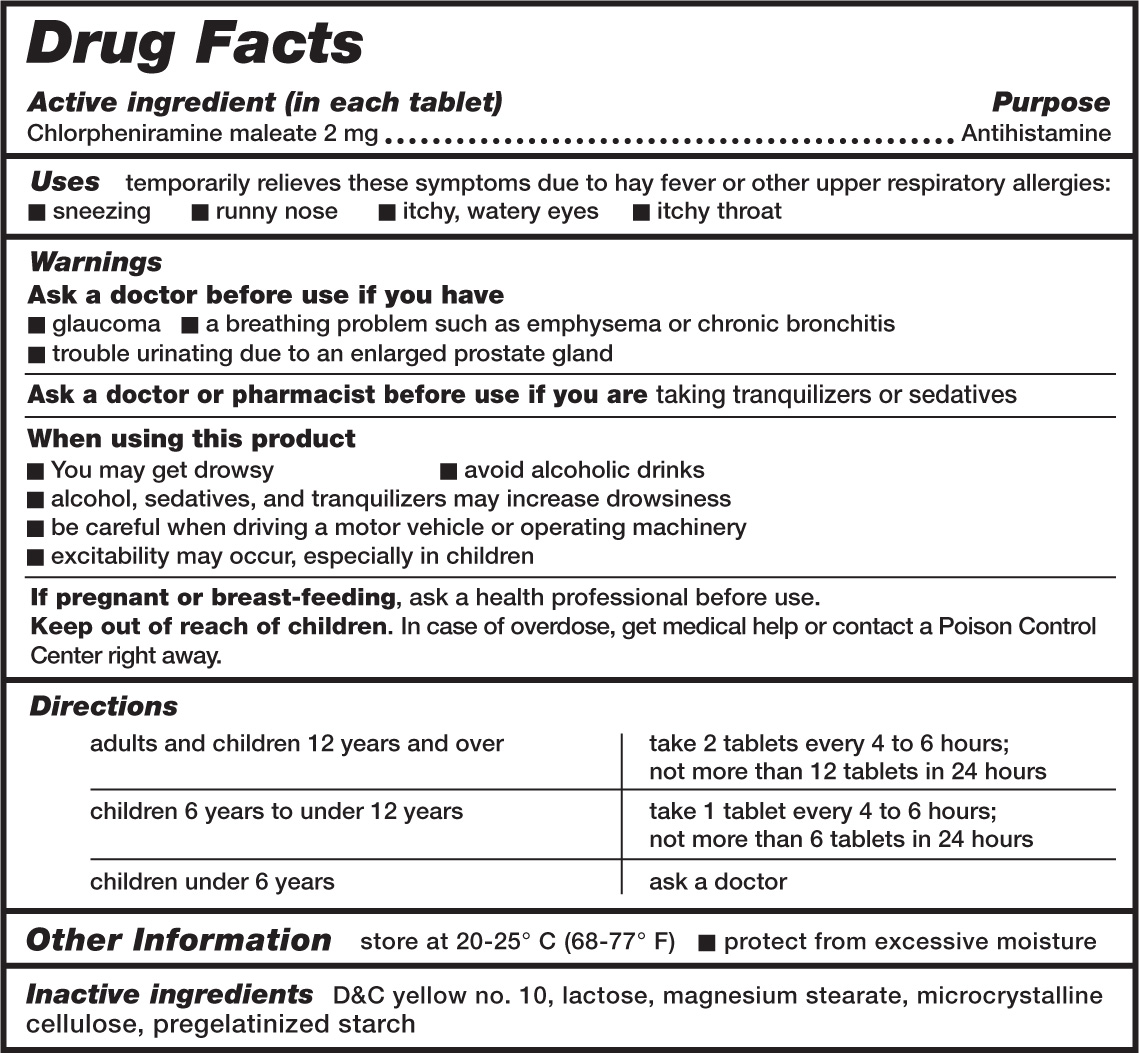

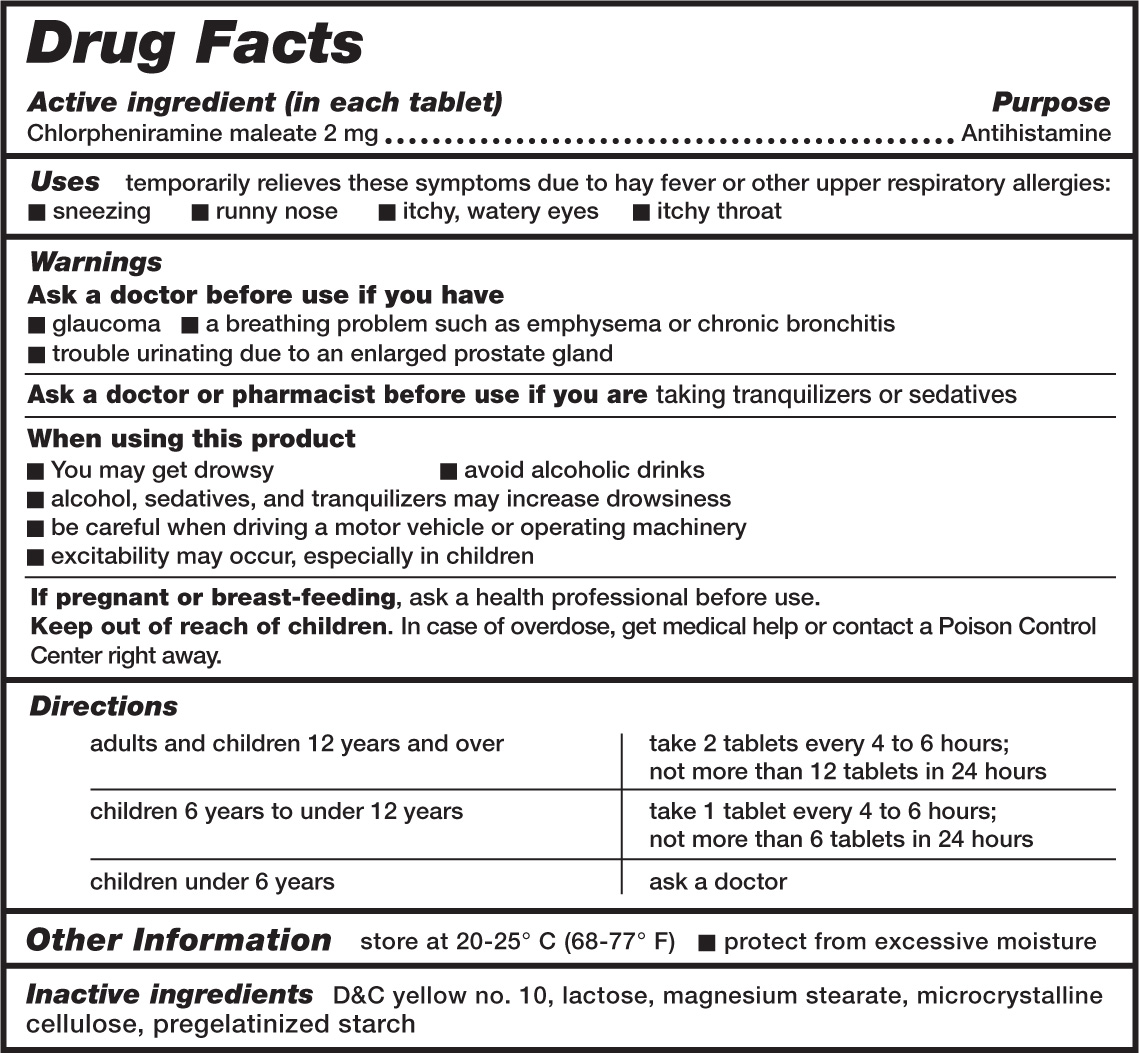

Because OTC medicines can be easily purchased from numerous sources without the benefit of instruction or advice from a physician or pharmacist, the FDA has recently instituted changes to improve product label directions. All OTC drug products are now required to contain standardized “Drug Facts” information (figure 3.1). All OTC drug product labels will provide information in the following categories:

• Active ingredient

• Uses

• Warnings

• Ask a doctor before use if you have . . .

• Ask a doctor or pharmacist before use if you are taking . . .

• When using this product . . .

• Other information

• Inactive ingredients

These standardized and simplified label directions should allow parents to use OTC products appropriately while minimizing administration errors.

You will more likely choose and administer safe and effective OTC liquid drug products for your child when you keep the following points in mind:

• Use your child’s weight, rather than age, when determining the appropriate dose.

• Use caution when choosing a product with more than one active ingredient. The extra ingredients may not benefit your child, and they may even cause adverse effects.

• Use only the dosing device that comes with the product package. Errors are more likely to occur if you substitute another measuring device.

• Read the label. Be sure to carefully read the Drug Facts to make sure the OTC product is considered safe and effective for your child.

• Be aware that some OTC pediatric drug products should not be given to children. Even though their availability may suggest otherwise, some OTC drug products, such as antidiarrheal medications, may not be safe and effective for children.

FEVER

Treating a fever in infants and children is the top reason parents and other caregivers reach for OTC medicines. You likely have given acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) to your child on numerous occasions. Fever is the most common concern when parents call their pediatrician, and it is a major reason why infants and children are taken to acute care clinics and hospital emergency departments.

3.1. Example of a “Drug Facts” medicine label. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration, fda.gov

Fortunately, the vast majority of fevers are not dangerous to your child. Many parents harbor “fever phobia,” a fear of fever that is often not based in medical reality. The phrase “fever phobia” was coined in 1980 by Dr. Barton Schmitt, the author of a published study that surveyed parents about fever and its effects. Dr. Schmitt found that many parents’ concerns and actions about fever did not match medical science. For example, many parents believed that a fever could damage an infant’s or child’s brain. And some parents would administer acetaminophen or ibuprofen to reduce a fever even when their child appeared comfortable. Several other recently published surveys of parents’ thoughts about fever show similar findings: the bottom line is that parents often over-treat their children with regard to fever.

The body temperature many parents consider to be a fever is often not evaluated as a fever by a health care professional. Medically, a normal body temperature is defined as between 97.8°F and 100.3°F, and a fever is defined as a body temperature of 100.4°F (38.0°C) or higher. These published surveys have found that while many parents would consider a specific body temperature to be high for their child, pediatricians would not, and they would not diagnose a fever at that body temperature. An elevated body temperature is not harmful unless a person has very high temperatures, greater than about 106°F, for a prolonged period. This occurs very rarely in children with an infection. Higher body temperatures, temperatures above 105°F to 106°F, can occur with hyperthermia or heat stroke, but these conditions are rare in children.

A fever is not an illness per se but a symptom of an illness or medical condition. Pediatricians are most concerned about the cause of the fever, and they consider the actual body temperature as less important. Studies and surveys have found that parents are often most focused upon, and concerned with, their child’s actual body temperature. From a medical science perspective, fever is an indication that the child’s immune system is active and functioning normally to combat the cause of fever, which most commonly results from a viral or bacterial infection. Many published studies of laboratory animals with fever have shown that suppressing a fever increased the likelihood of the animals dying from the infection that was causing the fever. So, a strong argument can be made that fever is a beneficial response to infection.

National guidelines on the treatment of fever have been published by the American Academy of Pediatrics. These guidelines state that the primary goal of treating fever “should be to improve the child’s overall comfort rather than focus on the normalization of body temperature.” Certainly all parents would like their ill child to be comfortable and feel better, but reducing a child’s body temperature to 98.6°F is not necessary to achieve his or her comfort. Acetaminophen and ibuprofen—antipyretic medicines—have benefits, such as improving comfort and allowing your child to return to normal eating, drinking, and sleeping behaviors. Some parents may believe that treating fever and decreasing body temperature reduces the duration and severity of the underlying condition producing the fever. No scientific evidence supports this for the majority of children. A decrease in body temperature can benefit some children with certain specific chronic diseases or severe illnesses by reducing metabolic complications of the illness, but these conditions are uncommon.

When your infant or child develops a fever, you may need to call your pediatrician. When you speak with your pediatrician’s office, they likely will want to know your child’s temperature and how you measured it. Depending upon your child’s age, underlying medical conditions, and other symptoms, the pediatrician may recommend that you bring your child into his or her office or to the hospital emergency department. However, this is often not necessary, and you may be able to treat your child at home, with careful observation for worsening symptoms. Your pediatrician will ask you about your child’s activities, behavior, and eating and drinking. Infants and children with a fever often do not eat and drink as much as they normally do, and they can quickly become dehydrated. Young infants, about 6 months of age and younger, should be very carefully observed, as they can become ill more quickly than older infants or children.

A normal dose of acetaminophen or ibuprofen will likely lower your child’s body temperature by about 2 or 3°F. So if your child has a fever of 103°F to 104°F, acetaminophen or ibuprofen will decrease the temperature to about 100°F or 101°F, and not 98.6°F. But this temperature reduction will likely allow your child to feel better, which is the goal of treatment. Focus on how your child feels and the activities or other symptoms you discuss with your pediatrician; don’t focus on the actual body temperature.

Either acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) can be used to treat your child’s fever. They are both effective and safe for infants and children when used appropriately. There are some differences between them, however, that may be important for your child. Your pediatrician will offer guidance. The most important point to understand when using either acetaminophen or ibuprofen is not which product to use. Rather, the key considerations are to give an appropriate dose to your child, not to give this dose too often, and to use your child’s comfort and activity, not body temperature, as a guide to help you decide if further doses should be given.

Table 3.1 compares features of acetaminophen and ibuprofen. Note that the dose differs between the two, and that ibuprofen can be given less often since its duration for lowering fever is about two hours longer. Also note that ibuprofen is not recommended for children younger than 6 months, as it has not been well studied and tested in these younger ages. Weight-based doses for acetaminophen and ibuprofen are listed in the table as well. Doses based on your child’s weight are most accurate, although dosing by your child’s age can be also be used. For example, dosing by age is listed on the bottle and packaging of infants’ and children’s liquid Tylenol and Motrin products. When you determine a weight-based or age-based dose for your child, always use the dosing device (oral syringe or dosing cup) that comes with the product, and use the closest appropriate volume marking on the device, such as 2.5 mL, 5 mL, 7.5 mL, and so on.

Ibuprofen is more likely to produce adverse effects to an infant or child’s kidneys as compared to acetaminophen. This may occur if your child is dehydrated or has other medical conditions that your pediatrician will discuss with you. Several studies have evaluated the potential benefit of treating fever with acetaminophen and ibuprofen combined, or by alternating doses of acetaminophen and ibuprofen. These studies have not demonstrated a clear advantage to giving acetaminophen and ibuprofen together or by alternating doses. The guidelines published by the American Academy of Pediatrics discussed above do not recommend alternating or combining doses of acetaminophen and ibuprofen, as it may be confusing or cause more adverse effects than using either acetaminophen or ibuprofen alone.

Table 3.1 Acetaminophen and ibuprofen for fever

|

Acetaminophen* |

Ibuprofen |

Dose |

• 4½–6½ mg per pound, every 4–6 hours when needed |

• 2½–4 mg per pound, every 6–8 hours when needed |

|

• do not give more than 5 times in 24 hours |

• do not give more than 4 times in 24 hours |

Age |

• any age* |

• 6 months of age and older |

Duration of fever reduction |

• 4–6 hours |

• 6–8 hours |

Dosage forms available for infants and children |

• infants’ and children’s liquid—both contain 160 mg per 5 mL • “junior” chewable tablets—160 mg per tablet |

• infants’ liquid—50 mg per 1.25 mL • children’s liquid—100 mg per 5 mL • “junior” chewable tablets—100 mg per tablet |

*Although acetaminophen can be given to young infants, speak with your pediatrician before administering, especially to infants younger than 2 months.

I tell parents that acetaminophen is a very safe and effective drug to treat fever when it is used appropriately, which means giving correct doses and not giving it too often. However, acetaminophen can be dangerous when an excessive amount is given or when it is given too frequently, which can be toxic to the liver and lead to liver failure, which can be fatal. Many case reports have been published in the literature describing this danger. Risk factors for administering toxic amounts of acetaminophen in these case reports include dosing errors, such as accidentally measuring too much or determining too large of a dose when using liquid acetaminophen products, or giving acetaminophen doses too often. Some of these case reports have described parents accidentally giving their child an adult dosage form of acetaminophen, and consequently an excessive dose. Other scenarios that have occurred involved giving acetaminophen inadvertently from several different OTC medicines, such as giving separate OTC drug products for colds and for fever, all of which contained acetaminophen, without realizing that the overdosing with acetaminophen was occurring.

A stroll down the “cough/cold” and “pain” aisles of your local pharmacy will highlight the vast array of different OTC drug products you can purchase to treat your child’s cold or fever. It can be bewildering (and potentially dangerous) deciding which product is best for your child. Most OTC pediatric drug products for cold symptoms that contain several active ingredients will list acetaminophen in yellow highlighted print on the packaging box or bottle if it is one of the active ingredients. If your child has a common cold and a fever, be cautious about giving a multi-ingredient OTC cold product in addition to another OTC product with acetaminophen just for fever.

COUGHS AND COLDS

The common cold occurs more frequently in the pediatric population than in the adult population. In fact, infants and children will suffer between six and ten colds each year. With a typical cold producing symptoms of congestion, mild fever, cough, and throat irritation or discomfort for up to ten days, and the possibility of up to ten colds per year, it may seem that your infant or child is nearly continuously ill. When your child has a cold, he or she likely sleeps less, which means that you also sleep less. Parents want their child to feel better, and it becomes tempting to give an OTC drug product to relieve these symptoms. Multi-ingredient OTC cough/cold products contain a variety of active ingredient medicines, most commonly combinations of medicines to treat cough, nasal congestion, antihistamines (supposedly to reduce a runny nose), and perhaps acetaminophen or ibuprofen for fever.

Until about ten years ago, many OTC drug products were available to treat colds in infants and younger children, and these products were advertised and marketed specifically for treating infants and younger children. In 2008, upon recommendations from the FDA and additional voluntary changes from OTC product manufacturers, package labeling and instructions for OTC cough/cold products were changed to read, “Do not use in children under the age of 4 years.” Despite their previous availability for these young ages, and their continued availability for children 4 years of age and older, there are no data from clinical studies demonstrating that cough/cold products effectively and safely treat cold symptoms in infants and children. Instead, many published studies and summary reviews of these studies have shown that cough/cold products do not reduce symptoms of the common cold in infants and children, and they can be dangerous to use.

Yet many of these products remain available for purchase. If clinical studies have shown that these products are not effective and safe in children, why do they continue to be available as OTC products? The answer relates to the difference in effectiveness of OTC cough/cold products in children as compared to adults.

The active drug ingredients in OTC cough/cold products have shown some benefit in clinical studies of adults, and due to a lack of similar studies in children, it was assumed over 40 years ago, when OTC drug ingredients began to be formally evaluated, that cough/cold ingredients would have similar benefits in children. Pediatric doses were extrapolated from adult doses based solely on body weight, which is an inaccurate method to determine safe and effective drug doses for infants and children.

Although no data from clinical studies have demonstrated that OTC cough/cold products are effective in infants and children younger than 12 years of age, information has accumulated over the past 40 years showing that these products can be dangerous, and even fatal. From 2004 to 2005 an estimated 1,519 children younger than 2 years of age, as reported by the FDA, were treated in hospital emergency departments for adverse effects, including overdoses, associated with cough and cold drug products. Well over 100 deaths of infants and young children have been described in published reports where OTC cough/cold products were the sole cause or important contributive causes.

Although several doses of pediatric OTC cough/cold products are unlikely to be toxic, these reports have described scenarios where the products were used inappropriately by administration of doses too large, doses given too frequently, doses measured inaccurately (too much liquid), or administration of similar active ingredient medicines given from numerous OTC products resulting in accumulative large doses. These mistakes were easily made by parents, considering the difficulty in accurately measuring out small liquid doses and a desire for the medicines to help (as many people mistakenly believe, when it comes to medicine, that more is better). Thus, the FDA is continuing to review the effectiveness and availability of OTC cough/cold products for children older than 4 years, and new regulations may be issued on their use in the near future. It is best not to give an OTC product marketed for cough and cold symptoms to your child if he or she is younger than 12 years of age.

Your child may also develop a cough from a cold, and this can be troublesome especially at night, reducing sleep. Many OTC drug products are marketed for cough (antitussive), as single-ingredient products or as part of multi-ingredient cough/cold products. The most common antitussive ingredient in OTC products is dextromethorphan, found in products such as Robitussin DM. In 1997 the Committee on Drugs of the American Academy of Pediatrics published recommendations on the treatment of cough and stated that there are no data from clinical studies demonstrating that dextromethorphan effectively and safely reduces cough in children. Similar to other OTC cough/cold drug products, dextromethorphan has remained available in OTC products likely because it can be effective in adults, and this efficacy had been assumed years ago to be similar in children. However, children are not small adults, and this assumption is not accurate.

Two well-done studies have recently been published describing the beneficial effects of honey in treating children’s coughs. These studies evaluated various types of honey (such as buckwheat honey) given at bedtime, and demonstrated that cough was reduced. It is not known if other types of honey, such as clover honey (amber in color, and widely available in grocery stores), are as effective. Doses of honey given in these studies were ½ to 1 teaspoonful (2.5 to 5 mL) for children 1 to 5 years of age, 1 teaspoonful (5 mL) for ages 6 to 11 years, and 2 teaspoonsful (10 mL) for older children. Other than a single bedtime dose, how often these doses can be repeated was not studied, although every 3 to 4 hours as needed seems reasonable. Note that “teaspoonful” is described here, although I discussed in chapter 2 that current recommendations state not to use teaspoons or tablespoons as liquid medication measuring devices. This is still true. The accuracy of dosing honey, a food item, for cough is not nearly as important as it is for liquid medicines. Because honey may contain bacterial spores that can be dangerous to infants younger than 1 year, honey should not be given to any infant younger than 12 months of age.

Codeine is another drug that has been used to treat cough for many years; it continues to be available in some states without a prescription. Although codeine remains available in some OTC cough products, and is also included in several prescription liquid cough medicines, it should not be used as a cough suppressant in children. Evidence has accumulated over the past ten years demonstrating that codeine can produce a significant decrease in breathing in some infants and children. More than 20 cases of fatal respiratory depression have been documented in infants and children.

Codeine does not have any pharmacologic effect in the body and it is chemically altered (metabolized) by the liver to form morphine and another active metabolite. We have learned that the amount of morphine produced from codeine liver metabolism can vary widely from person to person. Some individuals may convert codeine to a lot of morphine, while others may convert codeine to much less morphine. Morphine is a potent inhibitor of respiration, or breathing. This concept that inherited genetic differences may affect how an individual responds to a drug is termed pharmacogenetics, and is an active area of drug research. For many years we have known that no studies exist to support the use of codeine as an effective cough suppressant in children, and in 1997 the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended not to use codeine for this purpose. In 2015 the FDA similarly recommended that codeine not be used to treat cough in children. In 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics published additional warnings on the dangers of administering codeine to infants and children, recommending that its use for all purposes in children, including cough and pain, be limited or stopped.

So what can you do to help your infant or child with a cough or cold feel better? As with all of the illnesses discussed in this book, an important first step when treating your child is to speak with your pediatrician. Some severe infections may initially appear to be a cold or fever in your child, but can quickly progress to a more serious illness. Your pediatrician will talk with you and monitor your child for changes. If your child has a common cold, consider using some of the treatments described below. They are likely to be beneficial and much safer than OTC multi-ingredient cough/cold drug products.

The common cold can produce many annoying and troubling symptoms in infants and children. A stuffy or runny nose can be especially troublesome to infants younger than 6 months of age because they have difficulty breathing through their mouths like older children can. Not being able to breathe while feeding can be especially distressing for a young infant. Several simple remedies are likely to help. Bulb suctioning devices for removing nasal mucus from infants and young children can clear nasal passages. A similar device is a nasal aspirator that allows you, through attached but separate tubing, to use your inspiratory breathing force to suck out congestion from your infant’s nose. Your infant’s nasal contents do not come into contact with your lips or mouth, but are collected into a separate chamber. An example is BabyComfyNose nasal aspirator (available online for about $15).

Other products that relieve symptoms and are likely to be safer than OTC cough and cold products include the following:

• Saline solution drops or sprays for nasal stuffiness help to loosen dried and plugged nasal mucus and to decrease nasal congestion and improve breathing.

• Cold water humidifiers (vaporizers) humidify the air in your child’s room, which will decrease nasal congestion.

• Honey for cough, for ages 12 months and older.

DIARRHEA

Diarrhea, called acute gastroenteritis, is another common reason that parents call their pediatrician or bring their child into a pediatrician’s office. The majority of diarrheal episodes in infants and children are due to viral causes, often referred to as “stomach viruses” or “stomach bugs,” and they usually self-resolve with time. Parents often focus on trying to stop their child’s diarrhea, but a more appropriate focus is to prevent the dehydration that often results from excessive loss of fluid.

Although several OTC products are marketed to treat children with diarrhea, they should not be used in children. These products include Imodium AD, Kaopectate, and Pepto-Bismol. Imodium AD contains loperamide, which is an antimotility drug. It slows down the movement of fecal material through the intestinal tract. While this may seem to be beneficial for stopping diarrhea, loperamide has been known to cause severe slowing of intestinal movement and intestinal blockage in some children, resulting in death. Kaopectate and Pepto-Bismol both contain the drug bismuth subsalicylate, which is chemically similar to aspirin and may result in dangerous adverse effects when given to children. These medicines may be helpful when taken by adults with diarrhea, but as I have stated often throughout this book, children are not small adults.

If your pediatrician assesses that your child is dehydrated, you will likely be told to give some type of oral rehydration solution (ORS). Common brands of ORS widely available in pharmacies and grocery stores are Pedialyte and Enfalyte. Pedialyte and other ORS products contain a specifically balanced mixture of glucose, sodium, potassium, and additional electrolytes. These body chemicals are lost in diarrheal fluid and need to be replaced to rehydrate your child and prevent further dehydration. Infants and young children can quickly become dehydrated from diarrhea and may need to be hospitalized if dehydration is severe.

It may be tempting to give your child water, juice, or other liquids. These should not be used, however, as they do not contain the balanced mixture of glucose and electrolytes that your child needs. Juices can increase diarrhea and fluid loss because they contain a lot of sugar and can produce additional fluid loss from the intestines. Unfortunately, many children dislike the taste of the commonly available ORS products. Pedialyte and other oral rehydration solutions are available in flavors (grape, bubblegum, mixed fruit, and others) and these probably have a better taste than the unflavored Pedialyte. Chilling Pedialyte in the refrigerator will also improve the taste. For older children, ORS products are available as freezer pops. It is best to give only small amounts (about 1 ounce) of ORS, but give it frequently, about every 10 to 15 minutes. If you allow your child to drink as much as he or she wants, the fluids will likely be vomited back up. This happened to me when my son was about 4 years old and suffering from diarrhea. I gave him too much fruit Pedialyte, a bright red liquid, and he vomited it up after a few minutes all over the white t-shirt I was wearing!

The term complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is used to describe a group of diverse medical and health care therapies and practices that are not considered to be part of conventional, or western, medicine. CAM is also referred to as holistic or integrative medicine. There are many forms of CAM, including herbal medicines, probiotics, homeopathy, acupuncture, hypnosis, meditation, and yoga, among many others. Some of these therapies, such as herbals and probiotics, are taken orally as capsules, tablets, or as powder formulations. Herbal medicines (such as echinacea), probiotics, and melatonin are products commonly available in many pharmacies and can be purchased without a prescription. The term “supplements” is also used to describe these alternative orally administered products. The FDA defines dietary supplements as herbal products, vitamins, minerals, and other dietary substances.

CAM therapies are commonly used in the pediatric population. The National Health Interview Survey, a large survey of representative US households conducted in 2012 (17,321 interviews) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), evaluated CAM use in children 4 to 17 years of age. This survey revealed that CAM therapies were used by 11.6 percent of children. CAM therapies are used to treat anxiety, musculoskeletal conditions, recurrent headaches, and colds in both children and adults. Parents who use CAM therapies themselves are most likely to use them with their children. The supplements most commonly used in 2012 by children 4 to 17 years of age were fish oil, melatonin, probiotics, and echinacea. Some parents give fish oil to their children with attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (see chapter 4 for more on this topic). Melatonin, probiotics, and echinacea are discussed below.

It is important to have an appreciation for the significant differences between CAM supplements and traditional prescription and OTC medicines. Laws regulating the manufacture and evaluation of product safety and efficacy of traditional medicines and CAM therapies are notably different. These laws are significantly less stringent for CAM therapies. As discussed in chapter 1, prescription medicines must be demonstrated to be safe and effective in animal and human clinical studies before they are approved by the FDA and made available to the public. For a typical prescription drug, documentation of product safety and efficacy entails thousands of pages of data and information that are submitted to FDA officials for careful review. Although the regulations and processes for labeling of OTC drug product ingredients are not as in-depth as those for prescription medicines, the FDA has been extensively reviewing all categories of OTC drug product ingredients for safety and efficacy for over 40 years, and this process is continuing.

In 1994, Congress approved the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), which regulates the manufacture and availability of CAM supplements. This law strives to reach a balance between consumer access to CAM products and the ability of the FDA to remove dangerous products from public availability when necessary. However, it is not nearly as powerful or stringent as the laws regulating the safety and efficacy of prescription and OTC medicines, a point that is important to appreciate and keep firmly in mind.

Under DSHEA, supplement manufacturers do not have to demonstrate stringent purity and potency standards as do pharmaceutical manufacturers of prescription and OTC medicines, nor do they have to prove safety and efficacy from human clinical studies prior to marketing and public availability. There are thousands of supplement manufacturers, and it becomes very difficult for the FDA to carefully inspect supplement manufacturing facilities to ensure that appropriate procedures are used to safely produce supplement products. The FDA has reported that supplement products are sometimes being manufactured in residential basements or laboratories the size of a bathroom.

The manufacturers of supplements evaluate the product safety, purity, and potency by the honor system. They do not conduct stringent human testing as is done with prescription and OTC medicines. As you may imagine, this invites problems. Consumers assume that supplements are safe and contain the ingredients listed on the product label, but there is no guarantee.

And what about efficacy? Although supplements are not rigorously tested for effectiveness, manufacturers cannot claim false statements of efficacy either. A common statement found on supplement product labels regarding potential benefits of the product is, “This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent disease.” Thus, when you buy a supplement product, there is often no proof that the product will effectively do what the packaging label or its advertising claims, or that the product actually contains the amount of active ingredient stated on the label.

Some conventional medicines, such as digoxin and aspirin, were originally discovered and synthesized from natural plant sources. Digoxin, derived from the foxglove plant, is a drug used for some heart problems. Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) is made from willow tree leaves. Clearly some plants have natural medicinal properties. However, there is a significant difference between the theoretical and potential medical value of a plant and the real, proven therapeutic benefits of its chemical components, and in what parts of the plant the medicinal chemicals are found.

The bottles and packaging of supplement products on display at the local pharmacy have a professional appearance, similar to OTC products. It is easy for a consumer to be lulled into thinking that herbal and supplement products are as safe and effective as OTC medicines, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen. However, this may be a false assumption. The specific plant components that are safe and effective to use by humans, including the exact amount, is best determined through rigorous testing by the standards and procedures used for studying conventional medicines. This testing often is not done with herbal products, and it is not currently required by law.

Some supplement products include wording like “all natural” or “natural” on the product bottle and packaging. It is easy to understand why someone might assume that because an herbal or other supplement product is “natural,” it must therefore be safe, perhaps even safer than prescription medicines. However, this assumption may not be accurate. There are recent reports providing evidence that supplements can be dangerous. The FDA has received over 6,000 reports of adverse effects, including more than 1,000 considered to be serious, and 92 deaths from supplements in recent years. Most recently, the FDA issued a “warning” about homeopathic teething tablets and gels available in at least one major national pharmacy chain after seizures and breathing difficulties occurred with their use.

Because supplement products are not rigorously evaluated for purity and potency, they may not always contain what is stated on the package label, and incidents of these inaccurate labels have recently been reported. In 2015 the New York Attorney General’s office evaluated several popular herbal products for their content and found that the majority did not contain the active ingredients listed on the product’s label. These products were sold at major national retailers, such as Target, Walgreens, Walmart, and GNC. Instead of the stated active ingredients, many of the products tested contained rice, houseplants, carrots, asparagus, beans, or peas. Some even contained peanuts, a potent allergen for some children. Although these products have since been removed from store shelves or reformulated to more accurately contain labeled ingredients, it is likely, since supplement manufacturing is not strongly regulated, that other products similarly do not contain what their labels list. Other published studies have included case reports of various herbal products contaminated with lead or potent prescription medicines, with high potential for toxicity when given to children.

Recent studies supported by the federal government’s National Institutes of Health have demonstrated that the human body contains up to ten times the number of bacteria, termed the human microbiome, as human cells. We are accustomed to associating bacteria with infection or disease, but many of the ones found in our bodies are termed “good” bacteria, since they aid in essential processes like digestion and maintenance of a healthy immune system. Most of these good bacteria are found in our gastrointestinal tract (where you might find about 500 different species of bacteria). What do these bacteria do for us? Recent studies suggest that they contribute to food digestion, help our immune systems defend against other dangerous types of bacteria, and assist with synthesizing vitamins, among other benefits. When an infant is born, his or her gastrointestinal system contains no bacteria, but immediately after birth it begins to become populated with good bacteria from the mother and the infant’s environment. We are beginning to learn and investigate the relationship between alterations in the human microbiome and human diseases.

Probiotics are “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” (International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics, 2014). A prebiotic is “a non-digestible food ingredient that benefits the host by selectively stimulating the favorable growth and/or activity of 1 or more indigenous probiotic bacteria” (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2010). The idea of giving “good” bacteria to humans is not new; it was first suggested over a hundred years ago. Each year medical journals publish hundreds of studies evaluating the benefits of probiotics. Their use in children has increased many fold in recent years. Your local health food store, and pharmacy, likely contains many different probiotic products on their shelves, as capsules, tablets, powder, and liquids. Some infant nutritional formulas also contain probiotics.

Probiotics have been studied for many uses in infants and children, and recent summary reviews and guidelines describing these studies have been published. Not all of these potential uses, however, have been shown by clinical studies to be effective. Benefits demonstrated by clinical studies and accepted by pediatricians include:

• decreasing the amount and frequency of viral diarrhea in otherwise healthy children—probiotics can decrease the amount and frequency of diarrhea by about 1 day, if given early, within 48 hours of the onset of diarrhea; and

• preventing diarrhea associated with using antibiotics—antibiotics can destroy normal good bacteria in the intestines, causing diarrhea.

Other studies have suggested additional benefits of probiotics, although the evidence is not as convincing as it is for the uses above. Studies are continuing, and we may have additional evidence of more probiotic benefits in the near future. Probiotics are considered supplements and some probiotic products may make claims on the package labeling that infer greater benefits than clinical studies have demonstrated. Before giving your child a probiotic product, talk with your pediatrician.

If you and your pediatrician decide that a probiotic will benefit your child, it is important to consider the type of bacteria contained in the product, and the amount, or dose, of the bacteria. Many probiotic products are available, and they differ widely by the specific bacteria and the amount of bacteria contained in them. Clinical studies documenting the benefit of a specific bacterial species of probiotic may not confirm that the same benefits apply to a different bacterial species. Also important is the dose, or the number of bacterial organisms contained in the product. Bacterial species demonstrated to be effective in the studies of viral diarrhea treatment and prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea are Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) and the yeast Saccharomyces boulardii. Listed below are specific probiotic products containing an appropriate number of these bacterial and yeast species and likely to be effective:

• Culturelle Kids

• Florastor Kids

• Florajen4Kids

Melatonin is a natural hormone produced in the brain and it functions to help regulate circadian rhythms (distinguishing day and night) and sleep. Melatonin is sold as a supplement to help people sleep and is available in different strengths and dosage forms. As reported in the 2012 National Health Interview Survey of children 4 to 17 years of age, melatonin is among the most commonly used supplements.

Before considering giving melatonin or an OTC drug to help your child sleep, speak with your pediatrician about using good sleep hygiene practices to help your child sleep better. When these steps are implemented, children often do not need a supplement or OTC drug. Good sleep hygiene includes having regular bedtime and wake-up times, avoiding screen time (television, computer use) just before bedtime, and other practical steps.

Studies have shown melatonin to be beneficial to children with attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other neurodevelopmental disorders. However, in otherwise healthy children, there are few data from clinical studies to support the use of melatonin to improve sleep. The most appropriate dose and the long-term adverse effects of melatonin use in otherwise healthy children are also not known. Some pediatric references maintain that it is reasonable to try melatonin for a short time if additional help is still needed after implementing good sleep hygiene practices. A dose of 2 to 3 mg may be tried. Some pediatric experts have expressed concerns about giving a medicine, and a hormone (melatonin is a hormone), to help otherwise healthy children sleep. If you try melatonin, keep your pediatrician informed, and it’s best to use it short-term only, no longer than one or two weeks.

Echinacea is a natural herb obtained from parts of the echinacea plant, including the leaves and roots. Because supplements are loosely regulated, herbal products advertised as containing a specific plant, such as echinacea, may contain widely varying amounts of different species of the plant and various parts of the plant. The effectiveness of the supplement depends on these fine points, which can make it quite confusing when trying to choose a specific product from the store shelf.

Echinacea is marketed for the treatment and prevention of the common cold and other upper respiratory tract infections. A relatively large number of studies have been published on echinacea, mostly in adults. Reviews of this information demonstrate that some studies have shown a mild benefit, while other studies have not demonstrated any benefit. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, part of the federal government’s National Institutes of Health, describes the overall treatment effects of echinacea as “weak.” One published study found that echinacea caused an increased risk of rash in children.

I don’t recommend that you give your child echinacea until additional studies demonstrating its benefit to children are completed and published. There are several safe treatments you can use to help your child feel better from a cold (see the section on common colds, above), and they are likely safer and more effective than echinacea.

Vitamin products are a big business, as a visit to your pharmacy will demonstrate. It is likely that one entire aisle is dedicated to carrying various types of vitamin products, including multivitamins, separate vitamin products for vitamins B, C, D, and E, and various combinations of these vitamins. Children are the intended market for chewables, gummy vitamins, Flintstones vitamins, and more. Does your child need a vitamin supplement if he or she is a good eater? Would your child benefit from a vitamin supplement if he or she is a picky eater? Do vitamins have adverse effects if too much is given? These are good questions to ask your pediatrician, and I address them below.

The American Academy of Pediatrics states that healthy children who have a well-balanced diet do not need vitamin supplements. Children who do not eat well, are very picky eaters, or have specific diets, such as vegetarian with few dairy products, may benefit from a vitamin supplement. If you have such a child, it is best to speak with your pediatrician before purchasing a vitamin supplement. Some diseases and medicines may increase the need for specific vitamins. If your child requires additional vitamins because of a medical condition, your pediatrician will discuss this with you.

It is easy to think of vitamins as natural and safe, but it is possible to have too much of a good thing, with adverse effects. Some vitamins, namely fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) remain in parts of the body that have higher concentrations of fat for a significantly longer time than other vitamins, such as water-soluble vitamins (B and C).

Vitamin D has received specific attention recently by the American Academy of Pediatrics. In 2011, the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of vitamin D in pediatrics was raised. A major function of vitamin D is to increase the absorption of calcium and phosphorus from foods, and to increase and support bone function and strength. About one-half of an adult’s bone mass is stockpiled during adolescence, and by 18 years of age, we have about nine-tenths of our peak bone mass. Thus, obtaining sufficient quantities of calcium and vitamin D from a good diet are important throughout childhood.

Recent studies have shown that the majority of adolescents do not receive enough calcium through their diet. High amounts of vitamin D are found in many food sources, mostly dairy products, but also in shitake mushrooms and other vegetables (spinach, collards, and broccoli, for example), fatty fish (salmon, tuna, and other fishes), and some supplemented foods, including orange juice and various cereals. Milk is an excellent source of vitamin D. Dairy products, including yogurt, are also great sources of calcium.

Young infants sometimes require a vitamin D supplement. Since human breast milk does not contain an adequate amount of vitamin D, an infant who is sustained entirely on breast milk will need a supplement. If your newborn infant is entirely breastfed or even partially breastfed and partially formula-fed, your pediatrician will likely recommend a vitamin D supplement. All commercial infant formulas contain vitamin D, but an adequate amount of formula has to be consumed to meet daily vitamin D requirements (about 32 ounces of formula a day). Most newborn and young infants consuming formula will still require a daily vitamin D supplement. The current recommended dose of vitamin D is 400 international units (IU) daily for infants until the age of 12 months.

Milk is an excellent source of vitamin D and calcium. However, because the protein in cow’s milk is more difficult for infants to digest, and cow’s milk does not contain enough iron and other nutrients that young infants need, milk should not be given to infants younger than 12 months of age. However, starting at 12 months, children benefit from drinking milk.

Infants 1 year of age and children up to the age of 18 years require 600 IU of vitamin D daily. If your infant or child is healthy and has a good diet, including food sources high in vitamin D and calcium, especially dairy products, supplemental vitamin or calcium is likely not necessary. Children with certain medical conditions (such as cystic fibrosis) or those who use particular prescription medications may require supplemental vitamin D and calcium. Your pediatrician will discuss this further with you.

If you and your pediatrician decide that your child may benefit from a probiotic, vitamin, or other supplement, you will need to learn to select carefully. Because supplements are not as stringently regulated for purity, efficacy, and safety as prescription and OTC drug products, you should be aware of several characteristics that indicate if the product is likely to contain what its package label states.

When deciding on a specific product to purchase, be skeptical of words like “natural,” “all natural,” “certified,” or “approved” on the bottle or packaging. These words are meaningless and have no scientific or clinical benefit. There are seals from independent testing organizations that you can look for, however, and these do have some practical meaning and benefit.

• US Pharmacopeia (USP)

• Consumerlab.com

• NSF International

Supplement companies must pay a fee to the testing laboratories to evaluate their products. This testing is typically done one or several times per year. Look for the seal and name of these testing organizations on the product bottle.

One or more of these seals on a supplement product indicates that the product is more likely to contain what is stated on the product label and package, that it was produced using good manufacturing procedures, and that it does not contain other substances that can be dangerous to infants and children (as noted, some supplements recently tested have been found to contain lead, or even prescription medicines, so we know that some products are poorly manufactured).

Although the presence of the seals from the testing organizations indicates that the product is more likely to contain only what is on the product label, it does not imply that the product is therapeutically effective for a specific illness or medical condition, nor that the active ingredients have been proven safe by clinical studies. If your child is receiving any supplement product, be sure to inform your pediatrician and other health care providers. Parents often do not consider a supplement, such as vitamin, herbal product, or probiotic, a “medicine,” and they neglect to include it in a list of medications the child is receiving. However, it is important for health care providers to know what your child is receiving, including supplements, because some supplements may interact negatively with prescription or OTC medicines, and their use may affect additional treatment decisions and therapies that your health care provider may consider for your child.

Several reliable and informative Internet sites can help you evaluate specific supplement products to help you decide if your child will benefit from a supplement. These websites are:

• www.usp.org/USPVerified/dietarySupplements

website for the U.S. Pharmacopiea

website for the U.S. Pharmacopiea

lists many products that have been tested

lists many products that have been tested

website for NSF International, a public health and safety organization

website for NSF International, a public health and safety organization

• The cause of your child’s fever is more important than your child’s actual body temperature, as fever is not inherently dangerous.

• The goal of treating your child’s fever should be to increase comfort and improve eating and drinking, not to lower body temperature to normal.

• Either acetaminophen or ibuprofen can be used to treat your child’s fever, with some differences between them.

• When using acetaminophen or ibuprofen, it is important to systematically determine an appropriate dose and measure liquid doses carefully.

• Many OTC drug products for colds contain additional acetaminophen—be careful not to give your child more than one product containing acetaminophen.

• Acetaminophen can be toxic if too much is given.

• OTC drugs for cough and cold are not effective in young children and can be dangerous to use.

• Some remedies, such as saline nasal sprays and honey, can be effectively and safely used to treat your child’s cold symptoms.

• When your child has diarrhea, give oral rehydration solutions and not antidiarrheal OTC drug products.

• Complementary and alternative medicine products are not stringently regulated for potency, efficacy, and safety.

• Very little scientific information supports a benefit for use of echinacea or melatonin in children.

• Probiotics may help some children with diarrhea.

• Most children with a good diet do not require supplemental vitamins.

• Infants and some children will benefit from supplemental vitamin D.

• Be careful when choosing a supplement product, and look for products that have been evaluated by testing laboratories.