HOWARD W. BUFFETT

By 2009, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) was deeply entrenched in military conflicts across Afghanistan. That same year the U.S. government released an updated multiagency Counterinsurgency (COIN) Guide aimed at creating a “blend of comprehensive civilian and military efforts designed to simultaneously contain insurgency and address its root causes.”1 In line with this approach, the Secretary of Defense called on an economic development team to work in tandem with military command in theater to promote stability programs and business development throughout Afghanistan.2 Relying on military assets for the mission was critical, but the team’s combined civilian and military efforts were not combat-related, they were in support of economic stability goals.3 As the COIN guidebook stated, “Non-military means are often the most effective elements, with military forces playing an enabling role.”4 This multipronged approach was also in line with certain Afghan perspectives. In 2008, former finance minister (and future president) of Afghanistan Ashraf Ghani wrote that “collaborative partnerships across state, market, and civil society boundaries” were required to stabilize and rebuild economies in countries such as Afghanistan.5

The mission of the DoD economic development team spanned multiple industry sectors, numerous programs, and many provinces. The team brought together experts and investors from diverse backgrounds to consider “private-sector strategies to create a sustainable Afghan economy.”6 The agriculture sector in Afghanistan quickly became an obvious focus for the team, a perspective that senior military officials also supported at the time.7 This chapter outlines the strategy and project development that supported the DoD’s economic stability efforts in Afghanistan’s agricultural sector, specifically in Herat Province. The importance of cross-sector partnerships between the DoD and a number of private and public sector organizations is also explored.

The DoD’s initiatives addressed underlying economic and infrastructure challenges that led to improved agricultural output and employment in rural areas. This strategy was built on an early iteration of social value investing, with a primary goal of transforming beneficiaries of the programs into shareholders of the initiative’s outcomes.8 Specifically, the management approach and resulting programs treated the people of Herat as co-owners of the investments, with a sense of place-based permanence. Four closely linked and interrelated projects were initiated in the Herat area. These projects (1) increased a community’s production of agricultural commodities and (2) expanded nearby food processing capacity and job opportunities. The initiative also (3) organized large groups of farmers into more prosperous and stable cooperatives and (4) built a new agricultural college and related program capacity to serve important educational and research needs for the country.

AGRICULTURE IN AFGHANISTAN

Afghanistan is an agrarian economy: agriculture is its most important economic activity. Nearly 80 percent of Afghans live in rural areas,9 producing wheat, rye, rice, potatoes, fruits, and nuts.10 However, Afghanistan’s agricultural production faces significant challenges. Fewer than 12 percent of the country’s 161 million acres are arable,11 and a majority of farmers engage in subsistence or near-subsistence irrigated or rain-fed agriculture, cultivating only a few acres or less (figure 7.1).12

Figure 7.1 An Afghan village surrounded by subsistence farming. Smallholder plots such as those seen here characterize agricultural production throughout the country. Photo © Howard G. Buffett.

In the twenty-two years following the 1979 Soviet invasion, Afghanistan’s agriculture sector grew by only 0.2 percent annually.13 This compares with 2.2 percent growth during preconflict between 1961 and 1978.14 In 2010, the World Bank estimated that an annual rate of 5–6 percent growth (or more) would be required to support the country’s employment and economic needs.15 In addition, approximately 90 percent “of Afghanistan’s manufacturing industry and most of its exports” rely on agricultural production.16

Shortly after the DoD launched its economic development team in Afghanistan, it engaged the Norman Borlaug Institute for International Agriculture (the Borlaug Institute), centered at Texas A&M University. Borlaug Institute personnel traveled to Afghanistan to assess and identify ideal locations to develop new agriculture-based programs. These assessments, outlined later in the chapter, illustrated that investing in Herat Province’s agricultural sector would be an effective way to employ Afghans and improve food security and stability.

FOOD INSECURITY AND POVERTY IN HERAT

Herat Province suffers from pervasive food insecurity and malnutrition. At the time of the economic development team’s first assessments in 2009, one-third of Afghans lived below the minimum healthy daily caloric intake.17 Such chronic malnutrition diminishes physical and mental development for children and limits work productivity in adults.18 Herat’s food insecurity was largely the result of cyclical poverty perpetuated by decades of war and conflict.19 Researchers have documented the link between poverty and recurring conflict in many poor countries. For example, Oxford professor Paul Collier found that 73 percent of the world’s poorest citizens suffered a civil war during the ten-year period between 1993 and 2003.20 Afghans understood this well: in a 2009 survey, 70 percent of those interviewed perceived poverty and unemployment as the major causes of conflict in their country.21

Rural or remote areas often magnify the effects of poverty and conflict because residents lack access to advanced health and human services, wholesale or retail markets for commodities, or steady employment.22 In 2009, over 70 percent of the nearly two million residents of Herat Province were living in rural areas.23 DoD research estimated that approximately two-thirds of these residents were unemployed and that 300,000 additional jobs would be required by 2020 just to maintain the status quo.24 Reports also estimated that this unemployment would spike to as high as 90 percent of residents during winter seasons when reliable agricultural jobs disappeared.25 The Borlaug Institute estimated that 46 percent26 of the residents of rural Herat Province earned less than $2 a day, or about $600 per year.27 Without reliable employment and livable wages, most of Herat’s residents could not purchase nutritious food throughout the year. According to Afghanistan’s Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development, this situation threatened security and stability throughout the province.28 Because of economic instability and unemployment, and because control of the district shifted frequently, the military classified Guzara district,29 a focal point for the development team’s efforts in Herat, as “amber” (transitional conflict).30

The region’s insecurity exacerbated already poor living conditions for its most vulnerable residents. Recurring hunger and limited economic opportunities disproportionately affected women and children in the area, which contributed to a worsening cycle of instability.31 To achieve successful and sustainable development, particularly in areas such as Herat, U.S. government efforts had to consider this. Therefore, the DoD strategy prioritized collaboration with women-focused organizations on economic empowerment programs—with investments going beyond typically funded prenatal, child health, and nutritional projects.32 In fact, engaging and empowering women through agriculture provides the best protection against the long-lasting effects of child malnutrition, according to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to food.33 Connecting these facts from a policy perspective, the Afghan government and the United Nations recently developed a countrywide strategy on women in agriculture. The strategy stated, “Empowerment of women is fundamental to reduce poverty, hunger, and improve food security,” arguing that successful agricultural projects require gender equity and greater economic integration across gender lines.34

A FOCUS ON AGRICULTURAL INFRASTRUCTURE

Food insecurity can corrode social cohesion and prolong conflict around limited natural resources. Agricultural productivity gains in the early stages of development can be indispensable, especially if they demonstrate a visible and meaningful impact on local communities.35 Because of this, Herat’s development plan had to take into account economic, social, and environmental realities, and its strategy had to focus on long-term sustainability rather than short-term assistance. The DoD economic development team determined that one of the most effective ways to do this was to invest in the agricultural sector value chain. As discussed in chapter 4, a value chain typically encompasses the various inputs, activities, and business functions that go into a product’s development, production, and delivery.36 It can be customized to include industry or sector-specific attributes. For example, stability and development programs that aim to support an agricultural value chain must consider year-round access to adequate nutrition as a core component of food security, and as a foundational aspect of prosperity, particularly in rural parts of the world.37

At the time of the DoD’s assessments, Herat’s agricultural sector faced several structural deficiencies: seasonal shocks (such as drought), limited skilled labor, dated scientific knowledge, and market failures along a broken and unpredictable value chain.38 Typically, during the traditional harvesting season from May through October, rural families in Herat produced sufficient staple crops of vegetables and grains.39 During peak season, processing capacity usually could not keep pace with production, nor was there adequate cold, cool, or dry storage for excess crops. Because there were few opportunities for processing, preserving, or storing raw goods, rural families did not have enough food for the entire year. In a province home to tens of thousands of malnourished children and adults, crops rotted in the fields during peak season.40 The need to alleviate market disjunctions in the food supply chain was obvious. The top priority of the project team was to support links between agricultural production and processing to ensure more consistent food availability in Herat and develop a steady source of income for families.

ASSESSING WHAT COULD AND SHOULD BE DONE

Because of the importance of agriculture in Afghanistan, the DoD economic stability team launched a dedicated group focused on agricultural development (the DoD Ag team). The DoD Ag team settled on a broad mission for its agricultural strategy: improve food supply and agriculture-related infrastructure to promote security, stability, and rural development throughout Herat. Because it was relatively secure, Herat was an attractive area for investment. Using counterinsurgency language, the DoD felt it could develop the region as an expandable “ink blot” of stability, which could spread to adjoining, less stable areas.41 As the economic benefits spread, they hoped Herat could drive commercial integration and intracountry trade throughout more of Afghanistan.

The DoD Ag team engaged the Borlaug Institute to identify and assess specific, actionable opportunities for agricultural development across Afghanistan.42 This study identified several important attributes of Herat Province, including its inexpensive and somewhat dependable electricity in the capital, suitable climate for crop growth, soil that was comparably rich, and relatively limited insurgent violence. The assessments also identified some isolated agricultural activities, including fruit and vegetable production, which were promising given the local conditions. These assessments reviewed potential areas for investment, as well as specific projects, using four categories (and a number of subcriteria):

■ Impact: the amount of revenue, employment, and political effect a successful project in the area would generate;

■ Feasibility: the condition of the existing supply chain, including reliable electricity, human capital, and financial investments;

■ Sustainability: the presence of clear and consistent market demand, and dependable logistics necessary for commodity trade; and

■ Speed: the time required to create a desired effect. In an unstable environment, projects that take too long often run the risk of disruption by insurgent actors or by funding interruptions. Therefore, timing was an important consideration to ensure that local communities actually benefited from successful project implementation.

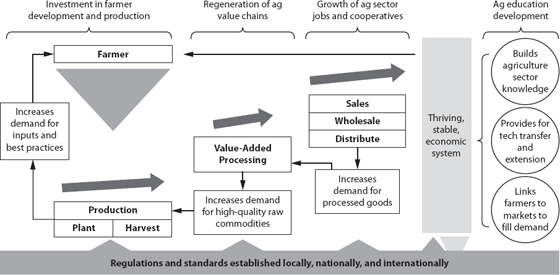

The first four potential project evaluations were for a poultry hatchery, a wholesale market, expansion of a grape farm, and development of a vegetable packaging and processing operation. Between the four, the vegetable packaging initiative received the highest score, in part because it supported and built on other investments in the value chain. The team conducted a preliminary analysis of external activities required to support the vegetable packaging initiative. Figure 7.2 illustrates a rudimentary list of partners and their functions relative to that analysis.43

Figure 7.2 Adapted from Norman Borlaug Institute Field Surveys and Analysis, this figure illustrates various partners and their functions relative to an integrated vegetable packing and processing operation under funding consideration.

INFORMING STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT

Following the research and assessment phase, the team developed a strategy centered on improving farm outputs, filling gaps in agribusiness processing, and driving demand for agricultural sector jobs. Further, these efforts strengthened the production, agribusiness, processing, livestock, crop, and horticulture subsectors of the broader agricultural industry throughout other parts of Afghanistan.

Many of the programs aimed to help farmers cultivating between one and five acres of land (figure 7.3). This group’s support would be valuable for rural long-term stability efforts because these farmers were often members of prominent local governing councils. They accounted for 60 percent of the population, farmed 80 percent of the land, and produced more than 80 percent of the agricultural output.44 When income increased for these farmers, so would the demand for rural nonfarm goods and services, which would create economic multiples and drive employment for many of the poorest citizens. Research indicated that this type of “middle market” farmer would more than double agriculture employment growth in Herat’s economy between 2010 and 2020.45

Figure 7.3 A smallholder farmer cultivating land in central Afghanistan. Photo © Howard G. Buffett.

Strategy development benefited from hundreds of in-field missions for data gathering, farmer interviews, and relationship building. Time in the field is particularly important when working with rural communities because it allows for consistent contact and for collaborative working relationships to develop. The team engaged local agribusiness and learned about the state of quality assessment and quality control, food safety, processing capacity, and product sourcing. Regional military commands were making their own investments in local agricultural development, which factored into the strategy, as did the existing capacity of farmer support services and programming at Herat University, especially as it related to cooperatives in the area.

The strategy also had to align with the broader military missions and the preexisting objectives and resources of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, which included:

■ Supporting operational needs of commanders in the field;

■ Maximizing measurable results in the early months of operation; and

■ Prioritizing opportunities for market-driven solutions.

The DoD Ag team strategy led to four mutually supporting projects in areas around Herat Province. The first project helped a group of rural farmers improve their access to underground water so they could irrigate their crops and expand their food production. The second project built nearby food processing centers, allowing expanded crop production to undergo value-added processing (turning tomatoes into tomato sauce, or wheat into flour for cooking). These centers also provided jobs, equipment, and training for underemployed women and increased local demand for raw agricultural commodities. The third project focused on forming cooperatives for large groups of farmers who were further out from the city of Herat. By pooling their resources, farmers could get bulk discounts and diversify their risk. The final project included construction of a new agricultural college at Herat University, along with staff resources, training, and laboratories for critical agricultural research.

MAKING THE STRATEGY WORK

The team developed its plans in line with the State Department’s recommendations in its “Afghanistan and Pakistan Regional Stabilization Strategy.”46 In broad terms, the strategy had four focus areas with objectives and implementation methods for each.

Strategic Area 1: Regenerate Agribusiness Value Chains

The team facilitated infrastructure and equipment investment to spur business creation and fill gaps in local supply chains by addressing market failures. Objectives included:

■ Improve crop production and inputs;

■ Prevent postharvest loss (through cold, cool, or dry storage);

■ Increase processing capacity and market access;

■ Enhance water usage and irrigation; and

■ Deliver resources and appropriate mechanization to cooperatives.

Agribusiness development in this strategic area relied on joint civilian-military efforts to connect farmers and farmer associations to markets through trade corridors, and it supported transborder facilitation.

Strategic Area 2: Invest in Farmer Development

The second strategic area supported farmer access to improved extension services. Extension programs, often operated as partnerships between local governments and universities, provide farmers with applicable scientific knowledge through non-formal education and training (by extending research and the classroom to the field).47 Improving extension would improve technical assistance to farmers through better procedures, curriculum, information delivery, and outreach services. This also supported a secondary goal of regaining rural support for the local Afghan government.

DoD partnered with leading U.S. agricultural extension universities (including faculty at Texas A&M University and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln) to gain their expertise.48 DoD also partnered with a new initiative, the Center on Conflict and Development, to add staff and research capacity focused on agricultural development in conflict regions, with an initial focus on Herat.49

Strategic Area 3: Grow Demand for Ag Sector Jobs and Cooperatives

The team prioritized increases in agricultural production through support to cooperatives. The main objectives were to create jobs and increase rural household income and prosperity. This also led to support for labor-intensive programs, such as watershed rehabilitation and rebuilding irrigation infrastructure, to help reintegrate former combatants into the economy. The team cooperated with initiatives already under way, such as the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Local Governance and Community Development program50 and the Commander’s Emergency Response Program (CERP) operated by the military.51 The team could then influence preexisting strategies and direct funding and support into related programs. Overlapping with existing government programs through interagency collaboration meant agribusiness activities and stability operations would be better coordinated and better resourced.

Strategic Area 4: Expand Agricultural Education and Research

The team’s final strategic area focused on the development of long-term national agricultural education, including infrastructure, curriculum, and both practical and advanced research capacity. The team worked with existing faculty and staff at Herat University’s College of Agriculture, as well as with the district office of the Afghan government’s Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Livestock (MAIL). Specific objectives for this strategic area included:

■ Expand the overall knowledge base for the agricultural sector through instruction and research;

■ Improve the quality of technology transfer from university research to producers;

■ Increase extension and outreach services provided by staff of the university and the Ministry of Agriculture; and

■ Provide linkages between farmers and local and regional sales markets, including capability for international exports.

INTEGRATING SOCIAL VALUE INVESTING

The DoD Ag team’s strategy used an early version of the social value investing framework described previously. Specifically, programs closely aligned with the framework’s people, process, and place elements.

People

By partnering with the Borlaug Institute, the DoD Ag team accessed world class talent, broad skill sets, and deep knowledge bases. The Borlaug team provided leadership and expertise needed for effective local capacity building and for identifying outside resources to support the program. Team members had training and advanced degrees in numerous agronomic subjects relevant to the strategy: agronomy, horticulture, marketing, quality control, value-added processing, cooperatives, extension, university education, and livestock. The team operated in a decentralized manner, conducting field visits throughout the villages and, at times, provinces around Afghanistan. They worked with local communities on a daily basis to identify opportunities to unlock intrinsic value that would have otherwise gone unnoticed by outsiders.

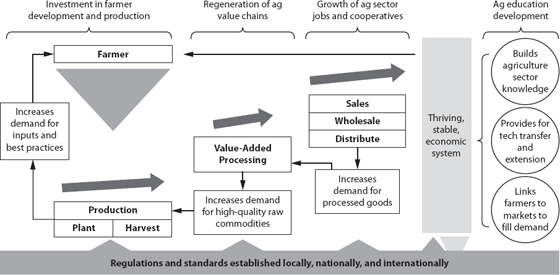

The team’s partnership process resulted in an expansive cross-sector approach, organized as a holistic value chain solution for the local community in Herat. The team recognized that a single break in the value chain would likely mean that funds invested upstream or downstream of that disruption would fail to have a sustained impact on a community. This collaborative approach required equipping and empowering people and institutions throughout the province, and it required new mechanisms to get products and services to market and create sufficient return on stakeholder investment. The team developed a simple value chain analysis mapped against the initiative’s key strategic areas (see figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4 Value chain analysis helps partners develop a comprehensive overview of program activities and gaps to fill in a region’s economic system. This diagram maps out aspects of Herat’s agricultural value chain within the context of the DoD economic development team’s four strategic areas.

Place

The team’s place-based strategy focused on investing in regional ownership and management to integrate local context into the design, development, and deployment of all aspects of the initiative. Stakeholders (including community groups and local political leadership) were involved in decision making from the beginning. These stakeholders were willing to coinvest their time, energy, and expertise in building a functioning, long-term, and healthy economic system that engaged the community in addressing its own challenges and maintaining long-term solutions. The DoD Ag team partnered with local institutions—both cooperatively and privately owned—as coinvestors in the projects. As articulated at the time, this strategy intended that the population receiving the benefit would become shareholders of the project’s outcomes rather than remain reliant as dependents on foreign assistance or donor aid.

The people, process, and place elements of social value investing were all represented by the initiative. Furthermore, financing for the program followed many of the principles of the portfolio element of social value investing. However, the programs relied heavily on the place-based aspects of the framework through locally driven project development and economic ownership for the communities.

HERAT’S PLACE-BASED INITIATIVE

Following the assessments and evaluation of proposals, the DoD Ag team identified four program areas for Herat’s place-based initiative.

Increase Community Production

Creating an economically sustainable model requires a comprehensive suite of solutions to fill gaps along the value chain. One critical gap in Afghanistan’s agriculture sector is access to water and irrigation infrastructure for crops. Herat is a semiarid climate, and irrigation is required for most crops during the dry season.52 Afghanistan once had an elaborate system of wells and belowground irrigation canals (called karez), but much of it was destroyed by decades of war and conflict.53 Conflict also hampered modern water management, resulting in inefficient resource use upstream (through methods such as flood or furrow irrigation) inadvertently harming farmers downstream by depriving their crops and livestock of water. Flood irrigation requires very little infrastructure, but it is incredibly wasteful and inefficient.54 Modern irrigation applies water through a long line of sprinklers that pivots in a circular pattern over large areas of land, often 160 acres. Such pivots apply water relatively slowly, can use low-pressure nozzles, and can reach as high as 98 percent water application efficiency. By comparison, flood irrigation is only 40 to 50 percent efficient.55 However, pivots typically require large fields and specialized maintenance, and they are capital intensive.

During the assessment phase, the Borlaug Institute spent time in a district east of Herat City, in the Rabāţ-e Pīrzādah village.56 The head of the local governance council (called a shura), Ghulam Jalani (figure 7.5), welcomed the DoD Ag team into the community to consider how the village could be more prosperous. Members of the community, as well as the Ag team’s assessments, identified the lack of irrigation as a chief constraint for crop production.57

Figure 7.5 Ghulam Jalani with a center pivot irrigation machine, installed in 2012, outside of the Rabāţ-e Pīrzādah village. Photo courtesy of Saboor Rahmany.

Some community members had seen a small demonstration irrigation pivot in Kabul and proposed the system as a solution for their farms. Jalani, a local farmer himself, knew that this project could make a significant difference for his village, and he worked closely with the DoD team to develop ideas. At first, it was unclear how a center pivot covering a large area could meet the needs of many individual small-scale farmers. The community proposed that its farmers coordinate their production cycles, adjust field boundaries, and grow complementary crops in specific zones under the pivot.

With community approval, the DoD Ag team evaluated well sites and tested water availability.58 They then managed procurement, delivery, and construction of new pivots, as well as maintenance and operations training programs with Herat University. Project success depended on a long-term and substantial commitment from the governor of Herat, who provided additional electricity infrastructure to power the pivots. Local government officials were continuously engaged to maintain their support for the project and to build support for similar projects based on lessons learned. In addition, the Borlaug Institute arranged for new varieties of crop seed to be available for sale to the farmers, so that they could take advantage of the improved water supply.59

Previous experience and contacts with global irrigation companies expedited the design and shipment process for the pivots, and the local community was eager to deploy the systems and benefit from better access to scarce water resources. By providing high-efficiency moisture application, these farmers could significantly increase yields for their wheat and double crop plants such as melon, cucumber, onion, eggplant, or tomato.60 This was especially important during the low rainfall months.

Near Herat city is the Urdu Khan Research Farm (a government-sponsored demonstration farm and research facility).61 Researchers at the farm were similarly interested in deploying a center pivot to conduct field research and rigorous data collection and analysis. Urdu Khan, the DoD team, and Herat University partnered on a research program to inform expanded use of irrigation systems in Herat and potentially elsewhere in Afghanistan. This included adaptive and comparative research on varieties of corn, cereals, and other vegetables and plants.62 Following this project, the World Bank issued a tender for improved crop inputs and capacity development at Urdu Khan through its Afghanistan Agricultural Inputs Project (AAIP) initiative.63 As of 2016, the Afghanistan government’s Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Livestock was actively working to expand this project and its research at the Urdu Khan facilities.64

Build Community-Based Value

Increases in crop production meant increases in raw produce as well. It was critical that additional output from the pivots be met immediately with expanded value-added processing capacity. Otherwise, local prices could suffer, and excess production might spoil.65 The DoD Ag team worked concurrently on new, women-owned cooperative food processing centers. These centers were reasonably straightforward to develop with short start-up times, they increased living standards for employees, and they helped stabilize local food supplies. New jobs and improved food security also created positive visibility in the communities, which yielded additional direct short-term benefits.

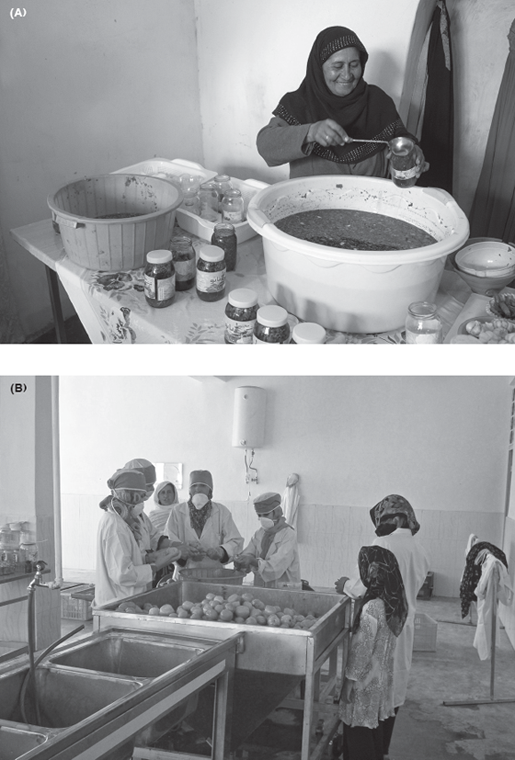

Simple food processing activity was already taking place in communities neighboring the center pivot projects. A local Afghan NGO, for example, focused on providing jobs for women by supporting in-home, rudimentary operations. However, these activities were limited in scope and had little or no quality control (figure 7.6a). The DoD Ag team hoped to leverage the preexisting relationships and experience in place and collaboratively established new Women’s Food Processing Cooperatives (WFPCs).

The team conducted a thorough planning process, integrating the full range of stakeholders. In line with the social value investing framework, the team ensured that local Afghan community members played a leading role in designing each processing center and collaboratively developed marketing and distribution plans. These plans integrated local production and logistics information and provided a clear path for market expansion to Herat city and other rural towns. The team worked with technicians and employees at the centers to differentiate their product lines and expand processing operations from the current crop-dependent schedule of six to eight months to a more consistent schedule of nine to ten months. With proper training and equipment, the centers’ employees learned to meet quality and control standards (which was necessary for exporting), and the rural processing centers became profitable, self-sustaining, and scalable (figure 7.6b).

Figure 7.6 (a): In-home preparation and sale of processed goods in 2010 before project investments into the community. (b): A thriving cooperative store in the Herat area selling the community’s processed goods in 2017, years after the cross-sector partnership concluded. (a) © Howard W. Buffett, (b) courtesy of SIPA Case Collection.

Local residents worked with the team to build small-scale hot houses fitted out with the necessary supplies and equipment. This allowed local growers to jump-start production for the first growing season and provide high-quality produce to the food processing centers very quickly. By allowing farmers to grow fruits and vegetables throughout much of the year, the hot houses extended the time line of income-generating activity for farmers and employees at the processing centers. Developing the WFPC program included the training of technicians to assume responsibility for the full-spectrum of business and processing operations as well as creation of a maintenance fund for the building and equipment.66

Upon completion, the WFPC immediately led to new full-time jobs for local women, with a strong prospect for additional jobs as operations expanded. More goods and capital were exchanged between local farmers and the rural processing centers, and the production of pastes, sun-dried fruits, jams, and jellies processed from locally grown and harvested vegetables and fruits showed a significant increase.

This all led to a successful agricultural development model that was transferable, sustainable, and scalable for other parts of rural Afghanistan, especially other communities with similar demographic, economic, and political characteristics. The DoD Ag team focused on this effort because the early agricultural assessments indicated that fruit and vegetable processing had a high potential for success. Over time, the team continued to provide expertise, capital, and infrastructure to develop more fruit and vegetable cooperatives, also run by women.

Project team leaders for the WFPC adhered to two critical guidelines. First, they ensured buy-in from the local stakeholders every step of the way. Second, they maintained consistent stakeholder communication to ensure that funders and implementers were delivering a project that met local needs. The team engaged local stakeholders from the outset of the project, investing the time and energy to develop trusted relationships. Furthermore, the team did not develop the project until invitations for the initial assessments were received from the local shura and from the preexisting NGOs.

The community also assisted by helping to secure a location for the team to work while they oversaw the project and by maintaining frequent communication during program development. It was a truly balanced partnership; each group brought their own skills, expertise, and resources, and the project team coordinated outside private sector capital to construct the processing centers. Collaborative planning and open communication in the early stages of project implementation proved critical for success.

Ultimately, the program established stable, women-owned and -operated cooperatives that sourced, processed, and marketed local fruits and vegetables in Herat and the surrounding region. One of the processing centers, in the village of Ziaratja, prospered very quickly (figure 7.7). A year after the center opened, Afghanistan’s minister of agriculture named the center’s leader, Zainab Sufizada, the best commercial farmer of Herat Province.67

Figure 7.7 (a): Zainab Sufizada’s in-home processing operation in early 2011 before the cross-sector partnership. (b): A cooperative food-processing center operated by Zainab in late 2011, around the time of the project’s completion. (a) © Howard G. Buffett, (b) courtesy Mark Q. Smith.

Establish a Community-Centered Cooperative Model

Rural farmers’ associations existed in Herat long before the DoD Ag team began working in the area. However, farmers often struggled because their operations were small and they had rudimentary equipment, usually limited to hand and animal power.68 In rural areas, food from locally produced crops was readily available only during the growing season, but farmers frequently had to sell or eat what they grew immediately because there were few ways to store, package, or ship crops after the harvest.69 Farmers’ associations could not adjust production to changing market conditions, and income levels varied wildly throughout the year. Without better production and marketing capacity, the agriculture value chain remained disjointed, and rural citizens faced food insecurity and hunger throughout much of the year.70

To address these challenges, the DoD Ag team worked with the Borlaug Institute to establish a large farmer-owned group of cooperatives, the Herat Cooperative Council Growers Association (Cooperative Council). The project organized more than fourteen hundred farmers across several districts into “producer associations.” These associations connected farmers to processing facilities so they could access more reliable markets. This project complemented other projects implemented by the regional military command, which was in charge of security forces in the Herat region. This, in turn, supported more secure conditions for sourcing food, more equitable market prices, a more stable rural economy, and, most important, a sense of hope for a better life.

The Cooperative Council helped organize business activities and provided technical advice to fruit and vegetable grower’s associations in each active district. This initiative served three primary functions. First, it provided assistance to the coalition forces and Afghan communities through security, stability, and economic investments that would encourage conditions for reconstruction and development. Next, it assisted the adoption of effective business models among rural farmers and agribusinesses that were open, transparent, and reliable. Finally, it developed a comprehensive farm-to-table approach for small fruit and vegetable growers.

The DoD Ag team worked with Afghanistan’s Ministry of Agriculture and Herat University’s College of Agriculture to enhance the university’s applied research for improved fruit and vegetable cultivation. It also provided technical assistance including field inspection staff, crop variety selection, advice on planting and harvest dates, evaluation of soil fertility and water use, integrated pest management plans, and diagnostics on fruit and vegetable growing problems.71

In turn, the Cooperative Council supported adoption of new methods and technologies to compete with products from other countries (such as imported wheat from neighboring Iran). For example, the Council was better able to identify market demand fluctuations and forward pricing, and schedule increased or decreased processing capacity as a result. It also improved brand identity for local products. Jointly with the DoD Ag team, the group trained farmers in the cooperatives on how to develop business plans, including distribution, advertising, and overall market growth. Furthermore, the group identified supporting customer services that would increase market share for its raw goods and for the food processing center’s products.72

The Herat Cooperative Council Growers Association aimed to reduce hunger, poverty, and conflict by increasing economic well-being and food security in Herat’s rural communities. The initiative worked to coordinate on-farm planning, assist in the timely production of vegetables, and develop skills that Herat’s subsistence farmers needed to operate their rural fruit and vegetable farms. It also developed programs to provide literacy and technical skills these farmers did not have. The projects used or augmented existing agricultural infrastructure, which made them more likely to succeed. Moreover, the strategy developed small- and medium-size farms and strengthened local value chains, including the weak links, such as research and development, production, processing and preservation, and distribution.

In the first year of operations, funding from the development team provided base salaries for Afghan field consultants to work on quality control issues with participating farmers. In addition to providing a framework that would create new rural jobs, the field consultants advised the Council on operations critical to each surrounding community: crop planning, marketing, weed and pest management, and equipment maintenance and operations. From a trade and sales perspective, the training focused on developing marketing channels and on logistics such as shipping and payment processing. These activities increased participants’ professional and technical skills, bolstered the long-term economic viability of each village, and reduced the need to migrate from rural areas to city centers.

The program worked quickly to engage the fourteen hundred small-scale farmers identified across key villages and added new extension staff who could support agricultural efforts.73 University staff and students were involved in a collaborative exchange of data and information. The Council supported financial instruments for contracts and cooperative planning for more efficient product delivery. The DoD Ag team hired local staff as technical field personnel who could resolve issues the farmers faced, and this staff developed training for self-directed leadership based on improved and more accountable business practices.

In the end, the Cooperative Council initiative was a co-ownership model truly emblematic of the social value investing framework. By design, the model was directly applicable to other regions across Afghanistan. It was immediately scalable to twenty-seven thousand small-scale farmers in four surrounding districts to support the larger area’s development into a reliable source of products for wholesalers, processors, and exporters.74 The Council helped stabilize the region and improve the perception of Afghanistan’s military security there. The partnership also strengthened relationships between the government of Afghanistan and coalition forces—and support for the U.S. presence among local Afghans.

Invest in Long-Term Stability: Herat University

In addition to supporting a resilient end-to-end agricultural supply chain, an integrated development model requires investment in place-based institutions to advance human capital, conduct research, and translate academic expertise into value for farmers. To this end, the DoD Ag team worked on construction of a new agricultural college at Herat University. Agricultural colleges are one of the most important building blocks of a thriving, stable, productive agrarian economy. As institutions of higher education, they are committed to the long-term development of agricultural sciences, horticulture, and related subjects.

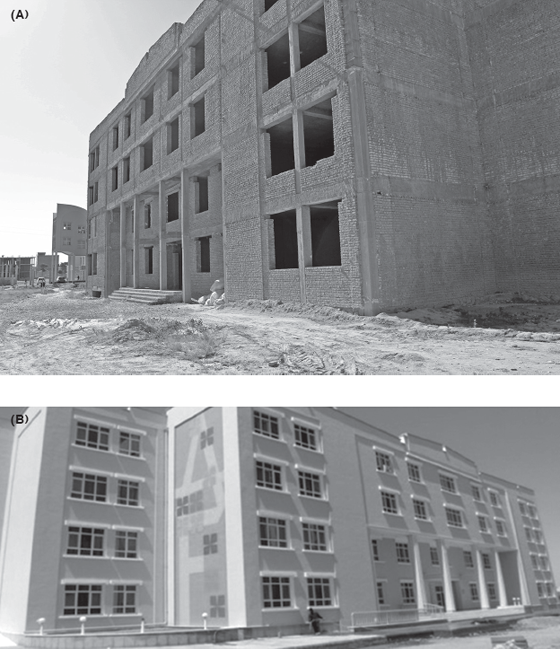

Plans for a new agricultural college at Herat University began years before the DoD Ag team arrived. The framework of a partially constructed building stood on campus for years, incomplete due to a lack of funding and political support.75 The DoD Ag team obtained the original blueprints for the building’s construction and worked with the university, the Borlaug Institute, and local contractors on cost and time estimates to complete the facility. The team had experience with this kind of project, having previously coordinated construction of the Dr. Abdul Wakil Agriculture College building at Nangarhar University in eastern Afghanistan.76

Once complete, the new agricultural college at Herat University was able to house thousands of students studying in existing agriculture-related departments as well as new departments created by the program (figure 7.8).77 The college was fitted with advanced laboratories for commodity and soil testing, and 130 students were able to learn from laboratory instruction at a given time.78 The DoD Ag team also coordinated equipment procurement, greenhouse construction, supplies for current and future operations, and provided technical expertise.

Figure 7.8 (a): Herat University’s agricultural college building sat partially constructed for years. (b): It was completed in 2013 as a result of the collaborative efforts of numerous partners. (a) courtesy of Lou Pierce, (b) courtesy of Richard Ford.

New programs provided the training and technical capacity for farmers in the area to increase production, meet advanced processing needs, and gain the skills and knowledge to access markets. By building an institution centered on enhancing agricultural productivity for years to come, the team anchored the other agricultural projects in the region—creating a truly comprehensive partnership process for one of the largest long-term stability challenges in Afghanistan.

As a first step, the team established a research-training program to train agricultural faculty to use the new laboratory facilities. This program was also open to regional agricultural ministry personnel, local staff of the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, as well as workers from a local flour processor.79 Prior to this program, neither the agriculture faculty nor the regional government staff had access to this type of advanced laboratory or the requisite training in analytical methods.80 The community benefited directly as the quality of teaching and research at the university improved significantly, as did the value of the government’s services to farmers. Rather than an academic research lab for a limited few, this project emphasized the importance of teaching and extension efforts to engage many in the agricultural community. The university developed a uniform curriculum of twelve classes that covered basic statistics and laboratory practices, lab work, and exams.81 It opened the course to all students, regardless of their gender, religion, background, or area of study.

Although some of the students failed the initial assessment test required to enroll in the course, these students worked with the instructors to develop a special independent study program outside of normal business hours. Fifty-five students enrolled in the first one-month program, of which fourteen were from outside the university (nine from the regional government).82 During interviews, the instructors spoke highly of the motivation of the students, especially because many of them were taking the course in addition to their normal employment or academic obligations. The class demographic was unusually diverse, attracting both men and women.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE AFGHANISTAN INITIATIVES?

The development team’s community-driven approach created a comprehensive and complementary set of place-based solutions for farmers in Herat. Each project aligned with the implementation strategy’s four strategic areas:

■ Investment in Farmer Development and Production was supported by the Herat center pivot irrigation systems, which allowed for more quantity and consistency of production.

■ Regeneration of Agribusiness Value Chains was supported by establishment of the Women’s Food Processing Centers, which provided new processing capacity to meet the increase in production from the center pivots.

■ Growth of Agricultural Sector Jobs and Cooperatives was supported by the Herat Cooperative Council Growers Association, which organized farmers for economies of scale, broader distribution and wholesaling of food, and a reduction in unemployment.

■ Expansion of Agricultural Education and Research was supported by the new College of Agriculture at Herat University, which provided support for the entire agricultural sector through extension, workforce readiness, technology transfer, cooperative advancement, and technical staff.

The Herat initiative was the most comprehensive set of place-based projects undertaken by the DoD’s economic development team, and it was an invaluable field test for the social value investing framework.83 This initiative was the team’s most ambitious effort to build cross-sector partnerships for agriculture in Afghanistan, and it engaged stakeholders across the entire agricultural value chain. The development team’s experiences in Herat were unique given the complexity of the setting, the resources brought to bear, the challenges, and the partners involved. Nevertheless, some of the lessons learned may be applicable to agricultural development projects elsewhere.

To succeed, these projects required local buy-in and the commitment from community residents to contribute what they were able to, such as the specialized labor for the women’s cooperatives. Building local buy-in may take time and is challenging in high-risk environments, but it was a significant contribution to the on-time and on-budget delivery of services—particularly the equipment installation and training at the women’s cooperatives and the successful implementation of the center pivots and the university training and development programs. The Herat team built productive working relationships with the military, USAID, and foreign government entities operating in the province, which further strengthened the programs.84

The working relationship between the U.S. and Afghan governments, private investors, and public institutions was a uniquely appropriate military-civilian collaboration for stabilizing the local environment. NGOs and the private sector often can move quicker and with more flexibility than government. Millions of investment dollars from public and private funding poured into Herat in alignment with the U.S. government’s objectives for regional agriculture and stability operations.85 Furthermore, funders would not have had the opportunity to survey these initiatives without support from the military for transportation and security. We have found only limited instances of cross-sector partnerships with military-civilian collaboration in conflict settings that combined private sector investment and philanthropic support for stability operations.86

Significant cultural barriers between the military, private sector, and the NGO community remain, but a clear and coordinated plan to facilitate cross-sector partnerships can overcome organizational differences. Under such difficult operating conditions, this was important for developing effective programming that did not solely rely on traditional fee-for-service contracts. The DoD Ag team acted as a broker for efforts in the region; in future partnerships, a similar secretariat could provide clear communication and manage various activities, relationships, and cultural nuances that develop throughout the partnership.

The Herat project looked comprehensively at the entire agricultural environment, well beyond isolated aspects of the agricultural industry. Addressing only one dimension of agricultural development could lead to more harm than good. Focusing on farmer production alone may serve a rural population’s needs for a short time, but failure to link those farmers to broader market opportunities could be disastrous.87 The assessment team saw this in parts of Afghanistan when farmers had a bumper crop but faced bottomed-out market prices. Some five thousand farmers in a district the Borlaug team evaluated planted tomatoes with the promise of later selling them to a development-aid-funded processing plant. However, these farmers were told four years in a row that the local “market disappeared” when they went to sell, and they were left with excess production and struggling incomes.88

The team’s assessments in Afghanistan relied on an expansive, context appropriate value chain analysis that looked at various links between training, crop production, processing, and marketing. The assessments informed key investment and resource allocation decisions such as focusing on vegetable and fruit processing and cooperatives. But the Herat project went beyond business supply chain analysis by factoring in the physical and human costs and benefits of the project. By implementing programs to improve human capital, cultivation methods, and the capability of agricultural institutions, the Herat team created a framework to strengthen the links in the value chain and create a healthier economic system that included support structures for agribusiness that have prospered in other places.

The teams focused on engaging experienced local management, and on fully integrating local preferences into strategic planning and program implementation. The team’s early assessments ensured that the necessary local capacities were in place to create effective partnerships. This was a productive collaboration between the government, private sector, philanthropic organizations, local NGOs, and the community, and everyone involved shared in the program’s successful outcomes.89