S PARQUE NACIONAL DESEMBARCO DEL GRANMA

S MAREA DEL PORTILLO TO SANTIAGO DE CUBA

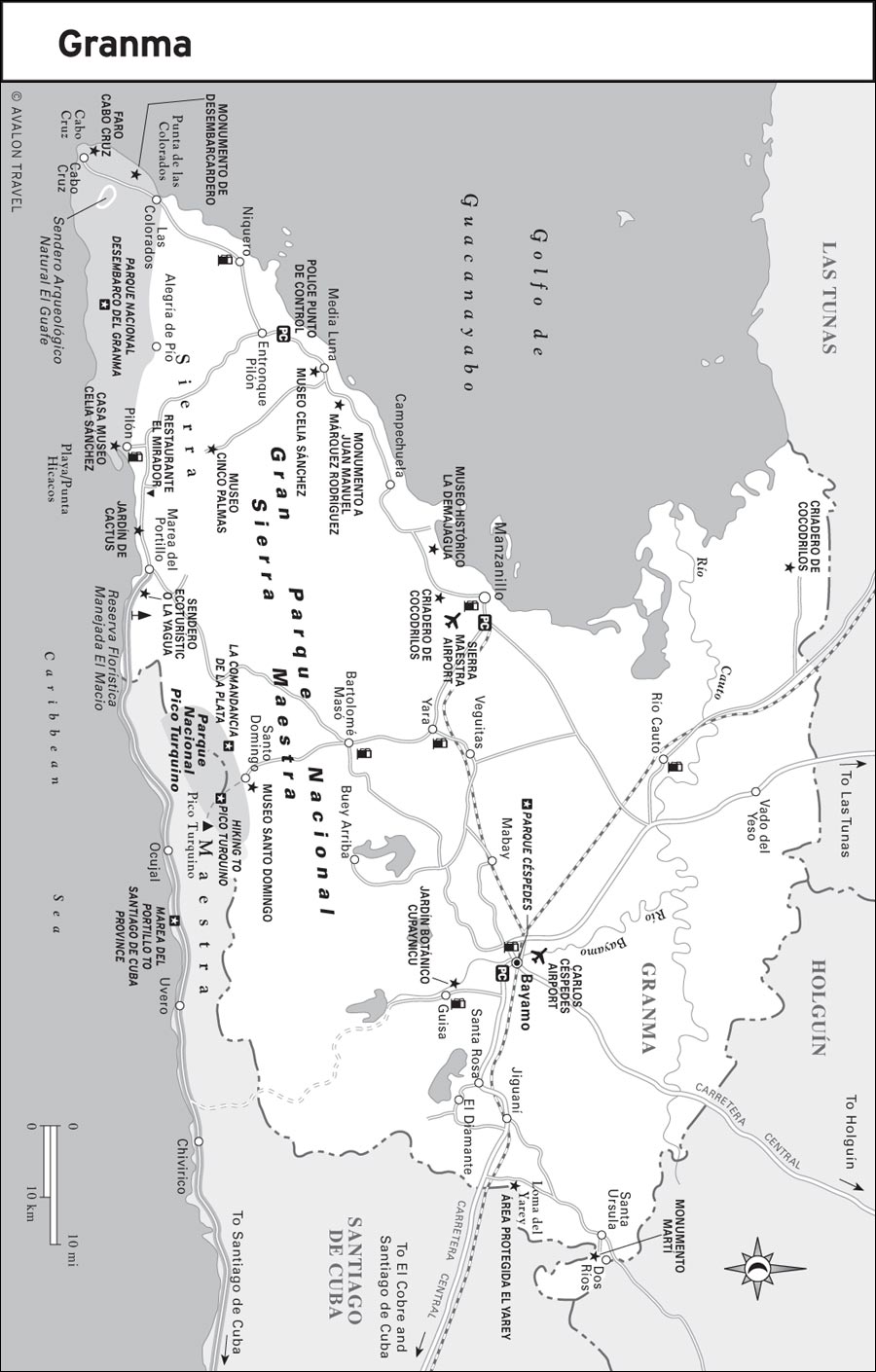

Cuba’s southwesternmost province abounds with sites of historical import. Throughout Cuba’s history, the region has been a hotbed of rebellion, beginning in 1512 when Hatuey, the local Indian chieftain, rebelled against Spain. The citizens of Bayamo were at the forefront of the drive for independence, and the city, which became the capital of the provisional republic, is brimful of sites associated with the days when Cuba’s criollo population fought to oust Spain. Nearby, at La Demajagua, Carlos Céspedes freed his slaves and proclaimed Cuba’s independence. And Dos Ríos, in the northeast of the province, is the site where José Martí chose martyrdom in battle in 1895.

The region also became the first battleground in the revolutionary efforts to topple the Batista regime, initiated on July 26, 1953, when Castro’s rebels attacked the Bayamo garrison in concert with an attack on the Moncada barracks in Santiago. In 1956, Castro, Che Guevara, and 80 fellow revolutionaries came ashore at Las Colorados to set up their rebel army. The province is named for the vessel—the Granma—in which the revolutionaries traveled from Mexico.

Several sites recall those revolutionary days, not least La Comandancia de la Plata (Fidel Castro’s guerrilla headquarters), deep in the Sierra Maestra. An enormous swath is protected within Gran Parque Nacional Sierra Maestra, fabulous for bird-watching and hiking. You can even ascend the trail to Pico Turquino, Cuba’s highest mountain.

For physical drama, Granma Province is hard to beat. The province is neatly divided into plains (to the north) and mountains (to the south). The Río Cauto—Cuba’s longest river—runs north from these mountains and feeds the rich farmland of the northern plains. The river delta is a vast mangrove and grassy swampland (birding is spectacular, not least for its roseate spoonbills). Whereas the north side of the Sierra Maestra has a moist microclimate and is lushly foliated, the south side lies in a rain shadow. Greenery yields to cacti-studded semi-desert.

Most sites of interest can be discovered by following a circular route along the main highway that runs west from Bayamo, encircles the Sierra Maestra, and travels along the south coast (road conditions permitting).

If you’re into the urban scene, concentrate your time around Bayamo, the provincial capital. Its restored central plaza—Parque Céspedes—and adjoining Plaza del Himno have a delightful quality and several historic buildings worth the browse. If you’re in a rush to get to Santiago de Cuba, it’s a straight shot along the Carretera Central, perhaps with a short detour to Dos Ríos (with a monument commemorating José Martí’s martyrdom here in 1895).

Fancy some mountain hiking? Then the Sierra Maestra calls. This vast mountain chain runs about 140 kilometers west-east from the southwest tip of the island (Cabo Cruz) to the city of Santiago de Cuba. The only area developed for ecotourism is at Santo Domingo, gateway to the trailhead to Pico Turquino (overnight hike) and La Comandancia de la Plata (same-day hike). The access road to Santo Domingo is not for the faint of heart; hill grades appear like sheer drops.

The town of Manzanillo has few sites of interest. The coast road south of Manzanillo, however, has sites sufficient for a day’s browsing. Of modest interest are the Criadero de Cocodrilos (croc farm) and Museo Histórico La Demajagua, the former farm where Carlos Manuel de Céspedes became the first landowner to free his slaves. Students of revolutionary history might check out the Museo Celia Sánchez (in Media Luna) and Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma, where Castro and his guerrillas landed to pursue the Revolution. The latter makes for a fleeting visit, unless you want to hike the trails (good for birding and caving) on the western slopes of the Sierra Maestra.

A singular reason to visit this region is the spectacular drive between Marea del Portillo and Santiago de Cuba. Running along the coastline for more than 100 kilometers, with the Sierra Maestra rising sheer from the shore, this roller-coaster ride turns a scenic drive into a fantastic adventure. There are virtually no communities en route. You’ll need your own wheels; public transport is extremely limited. At last visit, the road was dangerously deteriorated. Break the drive at Marea del Portillo, a ho-hum beach resort used by budget charter groups.

The region was the epicenter for an outbreak of cholera in 2012, centered on Manzanillo. The government acknowledged a reoccurrence in Bayamo in early 2013. At my last visit containment efforts were still in effect, including compulsory bleaching stations.

Bayamo (pop. 130,000) lies at the center of the province, on the Carretera Central, 130 kilometers northwest of Santiago and 95 kilometers southwest of Holguín. The town was the setting for remarkable events during the quest for independence from Spain. The historic core is a national monument.

Bayamo, the second settlement in Cuba, was founded in 1513 by Diego Velázquez as Villa de San Salvador de Bayamo on a site near contemporary Yara. It was later moved to its present site. Almost immediately Diego Velázquez set to enslaving the indigenous population. Slaves began to arrive from Africa as sugar was planted, fostering a flourishing slave trade through the port of Manzanillo.

By the 19th century, Bayamo’s bourgeoisie were at the forefront of a swelling independence movement. In 1867, following the coup that toppled Spain’s Queen Isabella, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes and the elite of Bayamo rose in revolt. The action sparked the Ten Years War that swept the Oriente and central Cuba. Other nationalists rallied to the cause, formed a revolutionary junta, and, in open defiance of Spanish authority, played in the parochial church the martial hymn that would eventually become the Cuban national anthem. With a small force of about 150 men, Céspedes seized Bayamo from Spanish forces on October 20.

In January 1869, Spanish troops were at Bayamo’s doorstep. The rebellious citizens razed Bayamo rather than cede it to Spanish troops. Internal dissent arose among the revolutionary leadership and the Ten Years War fizzled. Spanish troops left Bayamo for a final time on April 28, 1898, when the city was captured by rebel leader General Calixto García during the War of Independence.

Bayamo is laid out atop the eastern bluff of the Río Bayamo, which flows in a deep ravine. The historic core sits above the gorge.

The Carretera Central (Carretera Manuel Cedeño) from Holguín enters Bayamo from the northeast and skirts the historic core as it sweeps southeast for Santiago. Avenida Perucho Figueredo leads off the Carretera Central and runs due west to Parque Céspedes. Calle General García—the main commercial street and a pedestrian precinct—leads south from Parque Céspedes, paralleled by Calles José Martí and Juan Clemente Zenea, which merge south with the Carretera Central. To the north they merge into Avenida Francisco Vicente Aguilera, which begins one block north of Parque Céspedes and leads to a Y fork for Las Tunas and Manzanillo.

This pedestrian street (General García) runs south from Parque Céspedes for six blocks. It’s graced by ceramic tiles and sculptures, including lampposts turned into faux trees and bottles.

At Masó, four blocks south of the square, are four key sites. First up, the Gabinete de Arqueología (tel. 023/42-1591, Tues.-Fri. 8am-5pm, Sat.-Sun. 9am-noon, CUC1) displays pre-Columbian stoneware and other artifacts. The Acuario (no tel., Tues.-Sat. 9am-5pm and Sun. 9am-1pm, free) has two dozen tanks with tropical fish.

The Museo de Cera (Calixto García #254, tel. 023/42-5421, Tues.-Fri. 9am-5pm, Sat. 10am-1pm and 7pm-10pm, Sun. 9am-noon, CUC1 entrance, CUC5 camera), Cuba’s only wax museum, displays 10 life-size waxworks, from world-renowned Cuban musician Compay Segundo to Ernest Hemingway and Fabio di Celmo, the Italian tourist killed by a terrorist bomb in a Havana hotel in 1997.

La Maqueta (tel. 023/42-3633, Mon.-Fri. 8am-noon and 1pm-5pm, one peso), displays scale models of the city.

This beautiful square, bordered by Libertad, Maceo, General García, and Cacique Guamá streets, is surrounded by important buildings. At its center is a granite column topped by a larger-than-life bronze statue of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. There’s also a bust of local patriot Perucho Figueredo (1819-1870), inscribed with the words (in Spanish) he wrote for the himno nacional, “La Bayamesa”:

To the battle, run, Bayamesas

Let the fatherland proudly observe you

Do not fear a glorious death

To die for the fatherland is to live.

Céspedes was born on April 18, 1819, in a handsome two-story dwelling on the north side of the square. The house, Casa Natal de Carlos Manuel de Céspedes (Maceo #57, tel. 023/42-3864, Tues.-Fri. 9am-5pm, Sat. 9am-3pm and 8pm-10pm, Sun. 10am-1pm, CUC1, camera CUC5, guide CUC1) was one of only a fistful of houses to survive the fire of January 1869. Downstairs are letters, photographs, and maps, plus Céspedes’ gleaming ceremonial sword. The ornately decorated upstairs bedrooms are full of his mahogany furniture. His law books are there, as is the printing press on which Céspedes published his Cubana Libre, the first independent newspaper in Cuba.

The Museo Provincial (Maceo #58, tel. 023/42-4125, Wed.-Mon. 9am-5pm, Sat.-Sun. 9am-1pm, CUC1 entrance, CUC5 cameras) is in the house where Manuel Muñoz Cedeño, composer of the himno nacional, was born.

On the east side of Parque Céspedes is the house, now the Poder Popular (town hall), where Céspedes, as president of the newly founded republic, announced the abolition of slavery.

Parque Céspedes opens to the northwest onto the charming Plaza del Himno, dominated by the beautifully restored Iglesia Parroquial del Santísima Salvador (tel. 023/42-2514, daily 9am-11:30am), a national monument that amazingly survived the fire. The revolutionary national anthem was sung for the first time in the cathedral (by a choir of 12 women—the Bayamesas) during Corpus Christi celebrations on June 11, 1868, with the dumbfounded colonial governor in attendance. The church’s most admirable feature is the beautiful mural of Céspedes and the Bayamesas above the altar. The church occupies the site of the original church, built in 1516, rebuilt in 1733, and rebuilt again following the fire of 1869. It has a Mudejar ceiling and a baroque gilt altarpiece. On the north side of the cathedral is a small chapel—Capilla de la Dolorosa—that dates back to 1630.

The quaint Casa de la Nacionalidad Cubana (tel. 023/42-4833, Mon.-Fri. 8am-noon and 1pm-5pm, alternate Saturdays 8am-noon, free), on the west side, houses the town historian’s office and displays period furniture.

Also known as Plaza de la Patria, this small plaza is named for a revolutionary hero who, along with 24 other members of Fidel Castro’s rebels, attacked Batista’s army barracks on July 26, 1953. López survived, fled to Mexico, and was with Fidel aboard the Granma (he was killed shortly after landing in Cuba in 1956).

López is honored on the Retablo de los Héroes (Calles Martí and Amado Estévez), a bas-relief in the center of the square; in the Museo Ñico López (Abihail González, tel. 023/42-3742, Tues.-Sat. 9am-noon and 1:30pm-5pm, Sun. 9am-1pm, CUC1), in the former medieval-style barracks, 100 meters west of the square; at the tiny Sala Museo Los Asaltantes (Agusto Marquéz, tel. 023/42-3181, Tues.-Sat. 9am-5pm, and Sun. 8am-noon, CUC1), 50 meters southeast of the square; and on the Plaza de la Revolución (Av. Jesús Rabi, east of the Carretera Central), where the Monumento de la Plaza de la Patria features a bas-relief of heroes of the Granma landing.

Fireworks and candles are lit each January 12 on Parque Céspedes to commemorate the burning of the town in 1869, and a procession of horses symbolizes its abandonment. In mid-May, the city hosts the Festival de las Flores—a flower festival. Time your arrival for August 6 to catch the annual carnival, when neighborhoods compete with fireworks and floats.

The lively Casa de la Trova (Martí, esq. Maceo, tel. 023/42-5673, Tues.-Sat. 10am-1am, free by day, CUC1 at night) is fabulous for hearing traditional music. And bolero is performed each Saturday at 4pm at UNEAC (Céspedes #158, tel. 023/42-3670, www.uneac.com, free), in the Casa de Tomás Estrada Palma, where in 1835 Tomás Estrada Palma was born (he became the first president of Cuba following independence).

The Sala Teatro José Joaquín Palma (Céspedes, tel. 023/42-4423) hosts drama, children’s theater, and folkloric performances. And the Casa de la Cultura (Parque Céspedes, tel. 023/42-5917, daily 8am-8pm) hosts cultural programs.

For charm, check out La Bodega (Plaza del Himno, tel. 023/42-1011, Fri.-Sun. 10pm-1am), a Spanish-style bodega with seats made of barrels and cart wheels. It has music in a patio overhanging the river canyon. A less lively but similar alternative is the nearby La Casona (Plaza del Himno, Sat. 11am-11pm, Sun.-Mon. 10am-10pm).

bust of Ñico López, Museo Ñico López

Local group Cubayam sings Beatles songs on weekends at the open-air Centro Cultural Los Beatles (Zenea e/ Saco y Figueredo, tel. 023/42-1799, Tues.-Sun. 7am-midnight, 5-10 pesos). Life-size figures of the Fab Four greet you at the doorway. And busty nude wooden figures hold aloft the bar at Bar La Esquina (Marmól esq. Maceo, tel. 023/42-1731, daily noon-1am), a clean modern bar playing music videos.

You can get your kicks at Centro Recreativo Cultural El Bayam (tel. 023/48-1698), opposite the Hotel Sierra Maestra, with a cabaret espectáculo (Sat.-Sun. 4pm and 10pm, CUC1).

Kids in tow? Parque Diversiones Los Caballitos (Av. Aguilera) is one of the most complete children’s fun parks in the country, with all the fun of the fair.

Among the better town-center options is Casa de Ana Martí Vázquez (Céspedes #4, e/ Maceo y Canducha, tel. 023/42-5323, marti@enet.cu, CUC20-25), a gracious home beautifully furnished throughout with antiques and chandeliers. The lounge opens to a shady stone patio. Ana hosts two rooms: One, in a loft, is like a honeymoon suite.

I enjoyed my stay with wonderful hosts at Casa de Manuel y Lydia (Donato Mármol #323, e/ Figueredo y Lora, tel. 023/42-3175, nene19432001@yahoo.es, CUC20), with a simply furnished, air-conditioned room with fan and shared hot-water bathroom. It opens to a spacious patio with a hammock and rockers.

I also enjoyed a stay at Casa de Nancy y Aris (Calle Amado Estévez #67, e/ 8 y 9, Rpto. Jesús Menéndez, tel. 023/42-4726, CUC20), a short walk from downtown. The delightful owners offer three air-conditioned rooms, all with fan and private bathroom. It has secure parking, and there’s a plunge pool on the roof.

The Hotel E Royalton (Maceo #53, tel. 023/42-2290, CUC31 s, CUC50 d low season, CUC40 s, CUC70 d high season), on the west side of Parque Céspedes, has an all-marble staircase leading to 33 small rooms with firm mattresses and modern bathrooms.

Islazul’s Villa Bayamo (Carretera de Manzanillo, tel. 023/42-3102, jservicio@villagrm.co.cu, CUC15 s, CUC24 d year-round), two kilometers west of Bayamo, has 12 uninspired air-conditioned rooms and 10 two-bedroom cabins, plus a swimming pool and small nightclub.

Cubanacán’s Soviet-style Hotel Sierra Maestra (Carretera Central, Km 7.5, tel. 023/42-7970, comercial@hsierra.grm.tur.cu, CUC25 s, CUC40 d low season, CUC28 s, CUC44 d high season), three kilometers southeast of the city center, is perfectly adequate for a night or two. Modern bathrooms are the high point of its 114 simply furnished rooms. It has a swimming pool, disco, and tour facilities.

Hotel Sierra Maestra

Bayamo is a bit of a culinary wasteland with no shortage of flies. Spanish-themed La Sevillana (Calixto García #171, e/ Perucho Figueredo y General Lora, tel. 023/42-1472, daily noon-2pm and 6pm-10pm) serves simple criolla dishes for pesos. It has dinner sittings 6pm-8pm and 8pm-10pm.

On the bulevar, Paladar La Estrella (Calle General García #209, e/ Lora y Masó, tel. 023/42-3950, daily 10:30am-10:30pm) is the nicest option, albeit simple. It serves criolla staples, such as shrimp enchilada (CUC3).

There’s even a vegetarian restaurant: Restaurante Vegetariano (General García, esq. Lora, Mon.-Fri. noon-2:40pm and 6pm-9:30pm, Sat.-Sun. noon-2:40pm and 6pm-10:40pm).

Tropi Crema (Mon.-Fri. 10am-10pm, Sat.-Sun. noon-midnight), on Parque Céspedes, serves ice cream for pesos. And the well-run Café Serrano (Carretera Central, esq. Estévez) is the place to savor freshly brewed coffee.

Infotur (tel. 023/42-3468, infogran@enet.cu), on the north side of Plaza del Himno, supplies tourist information. The Paradiso (Antonio Maceo #112, e/ 2da y Frank País, tel. 023/48-1956, paradisogr@scgr.artex.cu) cultural agency can provide information on cultural events.

The post office (tel. 023/42-3305, Mon.-Sat. 9am-6pm), on the west side of Parque Céspedes, has DHL service. Etecsa (Marmól e/ Saco y Figueredo, tel. 023/42-8353, daily 8am-7pm) has international telephone and Internet service (upstairs).

Banks include Bandec (General García, esq. Saco, and García, esq. Figueredo) and Banco Popular (General García, esq. Saco). You can also change foreign currency at Cadeca, on the Carretera Central, next to the bus station.

Hospital Carlos Manuel de Céspedes (Carretera Central, Km 1.5, tel. 023/42-5012) is west of the Hotel Sierra Maestra, which has a Farmacia Internacional (Mon.-Fri. 8:30am-noon and 1pm-5pm, Sat. 8:30am-noon).

The Consultoría Jurídica Internacional (Carretera Central, e/ Av. Figueredo y Calle Segunda, tel. 023/42-7379, Mon.-Fri. 8:30am-noon and 1:30pm-5:30pm) provides legal services.

The Aeropuerto Carlos Céspedes (tel. 023/42-7514) is four kilometers northeast of town. A bus operates between the airport and the Terminal de Ómnibus. Cubana (Martí, esq. Parada, tel. 023/42-7511, airport tel. 023/42-3695) flies between Havana and Bayamo twice weekly.

Buses arrive and depart the Terminal de Ómnibus (Carretera Central, esq. Augusta Márquez, tel. 023/42-4036). Víazul buses (tel. 023/42-2167, www.viazul.com) stop in Bayamo en route between Havana, Varadero, Trinidad, and Santiago de Cuba.

The railway station (Saco, esq. Línea, tel. 023/42-4955) is one kilometer west of the Carretera Central. Trains between Havana and Santiago de Cuba and Guantánamo stop here; others connect with Manzanillo.

You can rent cars from Havanautos (tel. 023/42-7375), in the Hotel Sierra Maestra.

Havanatur (General García #237, e/ Lora y Masó, tel. 023/42-7662), on the west side of Parque Céspedes, offers excursions (including city tours by horse-drawn coche), as does eco-focused EcoTur (tel. 023/48-7006, agencia@ecotur.grm.tur.cu), in the Hotel Sierra Maestra.

For a taxi, call Cubataxi (tel. 023/42-4313).

The Carretera Central runs east from Bayamo across the Río Cauto floodplain.

At Santa Rita, about 15 kilometers east of Bayamo, turn south one kilometer to reach the hamlet of El Diamante, where several families make a living carving marble into souvenirs. Check out the family cooperative of Yoelvis Labrada (tel. 5398-3017) and his home-made lathe made of a Lada gearbox, bicycle chain, shaft-drives, etc. from various vehicles.

At Jiguaní, a nondescript town 26 kilometers east of Bayamo, a road leads north to Dos Ríos (Two Rivers), the holy site where José Martí gave his life for the cause of independence.

On April 11, 1895, Martí had returned to Cuba from exile in the United States. On May 19, General Máximo Gómez’s troops exchanged shots with a small Spanish column. Martí, as nationalist leader, was a civilian among soldiers. Gómez halted and ordered Martí and his bodyguard to place themselves to the rear. Martí, however, took off down the riverbank towards the Spanish column. His bodyguard took off after him—but too late. Martí was hit in the neck by a bullet and fell from his horse without ever having drawn his gun. Revolutionary literature describes Martí as a hero who died fighting on the battlefield. In fact, he committed suicide for the sake of martyrdom.

Monumento Martí is a simple 10-meter-tall obelisk of whitewashed concrete in a trim garden of lawns and royal palms. White roses surround the obelisk, an allusion to his famous poem Cultivo una Rosa Blanca. A stone wall bears a 3-D bronze visage of Martí and the words, “When my fall comes, all the sorrow of life will seem like sun and honey.” A plaque on the monument says simply, “He died in this place on May 19, 1895.” A tribute is held each May 19.

The Loma el Yarey, a massif offering 360-degree views over the plains and towards the Sierra Maestra, is the core of Área Protegida el Yarey. However, it is closed to visitors.

A turnoff from the Carretera Central about two kilometers east of Bayamo leads south to Guisa, a charming town in the foothills of the Sierra Maestra. About one kilometer north of Guisa you’ll pass a Saracen armored car roadside: It’s now the Monumento Nacional Loma de Piedra, recalling the battle for the town that took place on November 20, 1958.

Two kilometers before reaching Guisa, a sign at La Nieñita points the way to the Jardín Botánico Cupaynicu (tel. 023/39-1330, Tues.-Sun. 8am-4:30pm, CUC2), at Los Mameyes. It’s named for a local palm, one of 2,100 species of flora found here. Two-hour guided trips are offered of the 104-hectare garden, divided into 14 zones, including palms (72 species, of which 16 are Cuban), cacti (268 species), rock plants, tropical flowers, etc., accessed via a 1.8-kilometer loop trail. It also has a greenhouse or ornamentals, plus an herbarium. Local tour companies offer excursions.

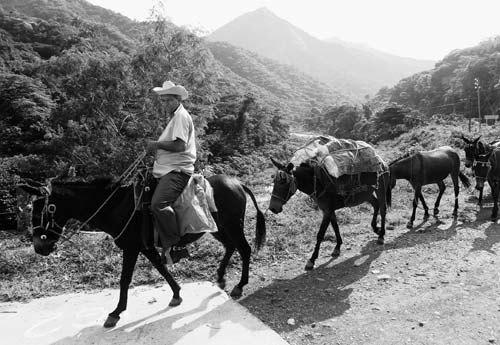

The Sierra Maestra hangs against the sky along the entire southern coast of Oriente, from the western foothills near Cabo Cruz eastward 130 kilometers to Santiago de Cuba. The towering massif gathers in serried ranges that precede one another in an immense chain rising to Pico Turquino. It is forbidding terrain creased with steep ravines and boulder-strewn valleys. These mountains were the setting for the most ferocious battles in the fight to topple Batista.

The hardy mountain folk continue to eke out a subsistence living, supplemented by a meager income from coffee.

This 17,450-hectare national park is named for Pico Turquino, Cuba’s highest mountain (1,974 meters). Fidel Castro had his guerrilla headquarters amid these slopes; the hike to La Comandancia is richly rewarding. So, too, is the challenging hike up Pico Turquino.

These mountains are also important for their diversity of flora and fauna. At least 100 species of plants are found nowhere else, and 26 are peculiar to tiny enclaves within the park. Orchids cover the trunks of semideciduous montane forest and centenarian conifers. Higher up is cloud forest, festooned with old man’s beard, bromeliads, ferns, and vines, fed by mists that swirl through the forest primeval. Pico Turquino is even tipped by marshy grassland above 1,900 meters, with wind-sculpted, dwarf species on exposed ridges.

The calls of birds explode like gunshots in the green silence of the jungle. Wild pigs and jutías exist alongside three species of frog found only on Pico Turquino, which looms over the tiny community of Santo Domingo, on the east bank of the Río Yara, 20 kilometers south of the sugarcane processing town of Bartolomé Masó (60 kilometers southwest of Bayamo). The road requires first-gear ascents and descents.

Santo Domingo was the setting for fierce fighting June-July 1958. The small Museo Santo Domingo (open by request, CUC1) features a 3-D model of the Sierra Maestra with a plan of the battles. Small arms and mortars are displayed.

Entry to the park is permitted daily 7:30am-2:30pm only (10am is the latest you are allowed to set off for Pico Turquino). A guide is compulsory, arranged through EcoTur’s Centro de Visitantes (daily 7am-10am) at Santo Domingo. You can book in advance through EcoTur (tel. 023/56-5635 at Villa Santo Domingo, Bayamo tel. 023/48-7006).

From Santo Domingo the corrugated cement road is inclined 40 degrees in places—a breathtakingly steep climb with hairpin bends. After five kilometers the road ends at Alto del Naranjo (950 meters elevation), the trailhead to Pico Turquino and La Comandancia de la Plata. The drive is not for the fainthearted, and not all rental cars can make it! Hire a jeep taxi (CUC5). To hike from Santo Domingo to Alto del Naranjo is a relentless four-hour ascent.

Fidel named his rebel army headquarters in the Sierra Maestra after the river whose headwaters were near his camp on a western spur ridge of Pico Turquino. The 16 buildings were dispersed over one square kilometer on a forested ridgecrest, reached by a tortuous track from Alto de Naranjo (CUC33 or CUC27 pp for more than four people, including transport, lunch, and entrance, plus CUC5 cameras, CUC5 videos) that’s a scramble over rocks and mud. The wooden structures were hidden at the edge of the clearing and covered with hibiscus arbors to conceal them from air attacks. Castro’s house was built against the ravine, with no visible entrance (it’s hidden) and an escape route into the creek. You’ll also see the small hospital (run by Che Guevara, who was a qualified doctor) and a guest house that is now a small museum with a 3-D model of the area, plus rifles, machine guns, and other memorabilia. Plata was linked by radio to the rest of Cuba (a transmitter for Radio Rebelde loomed above the clearing); it’s a steep and slippery ascent to the hut.

From Alto de Naranjo it’s 13 kilometers to the summit. Even here you cannot escape the Revolution. In 1952 soon-to-be revolutionary heroine Celia Sánchez and her liberal-minded father, Manuel Sánchez Silveira, hiked up Turquino carrying a bronze bust of José Martí, which they installed at the summit. In 1957 Sánchez made the same trek with a CBS news crew for an interview with Fidel beside the bust. Che Guevara recorded how El Jefe checked his altimeter to assure that Turquino was as high as the maps said it was.

The Sendero Pico Turquino begins at Alto de Naranjo (a 7am departure from Santo Domingo is recommended). En route you’ll pass through the remote communities of Palma Mocha, Lima, and Aguada de Joaquín. Hikers normally ascend the summit the same day, then descend to overnight in a dorm at Aguada de Joaquín.

From the summit, you can continue down the south side of the mountain to Las Cuevas by prearrangement; a second guide will meet you at the summit.

Hikers need to take their own food and plenty of water. You can buy packaged meals (CUC10) at Villa Santo Domingo. There are no stores hereabouts. Warm clothing and waterproof gear are essential (the mountain weather is fickle and can change from sunshine to downpours in minutes), as are a flashlight and bed roll.

EcoTur (tel. 023/56-5635 at Villa Santo Domingo, Bayamo tel. 023/48-7006, Havana tel. 07/641-0306, reservas@ecotur.grm.tur.cu) handles all visits and offers three guided hikes to the summit: Pico Turquino 1 (one night/two days, CUC68), with overnight at Aguada; Pico Turquino 2 (two nights/three days, CUC90); and Pico Turquino 3 (two nights/three days, CUC104), including La Comandancia de la Plata. Prices include transport, entrance, food, and water. Tip your guide!

Serving Cubans and backpackers, the riverside Campismo La Sierrita (tel. 023/56-5584, CUC6-8 pp), six kilometers south of Bartolomé Masó, has 27 simple two- and four-person cabins, plus a basic restaurant. You can make reservations c/o Campismo Popular (General García #112, tel. 023/42-4425) in Bayamo.

view of Pico Turquino from Santo Domingo

To sample local life, spend a night at Casa de Ernesto y Arcadia (CUC25 including breakfast), a humble home on the hillside opposite Villa Santo Domingo. The hosts are delightful. The sole room has a comfy double bed, fan, and a shared bathroom with modern toilet and cold-water shower in the garden. Bring mosquito repellent.

Islazul’s Villa Balcón de la Sierra (tel. 023/56-5613, vbasi@islazulgrm.co.cu, CUC14 s, CUC18 d year-round), on a windswept hillock 800 meters south of Bartolomé Masó, is a basic facility with 20 air-conditioned cabinas with meager furniture. The “suite” (merely a large room) above the restaurant is nicely furnished; a balcony offers spectacular views. It’s Restaurant Los Pinos (daily 7am-10pm) overlooks a swimming pool.

The best option is Islazul’s Villa Santo Domingo (tel. 023/56-5635, comercial@islazulgrm.co.cu, rooms CUC23 s, CUC36 d low season, CUC28 s, CUC45 d high season, bungalows CUC38 s, CUC44 d low season, CUC60 s, CUC70 d high season, including breakfast), on the banks of the river in Santo Domingo. It has 20 simple air-conditioned cabins, each with TV and modern bathrooms, plus 20 more luxurious quadplex two-story wooden “bungalows” (new in 2013). For a sense of adventure, opt for two-person tents pitched on a canopied deck (CUC3 pp). An open-air riverside restaurant serves criolla staples.

If you tire of the hotel fare, head downhill 200 meters from the hotel to Paladar La Orquidea, a charming little wooden home with rustic patio dining overlooking the river.

A camión departs Masó for Santo Domingo on Thursday at 5:45am and 4pm and departs Santo Domingo for Masó at 8am and 6pm.

A jeep-taxi from Bayamo costs about CUC35 each way, CUC10 from Masó. Anly Rosales Benítez (tel. 5292-2209) is recommended.

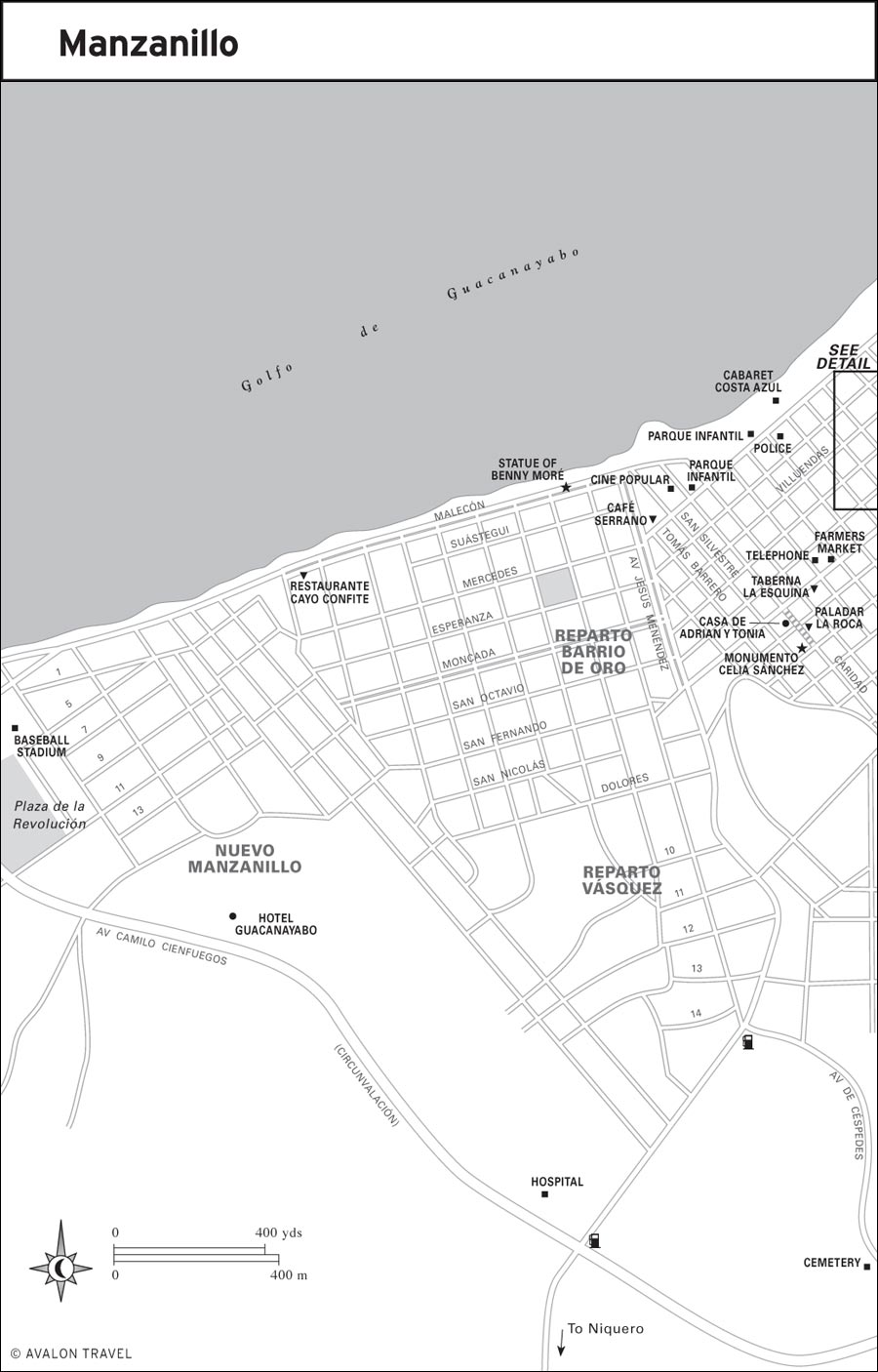

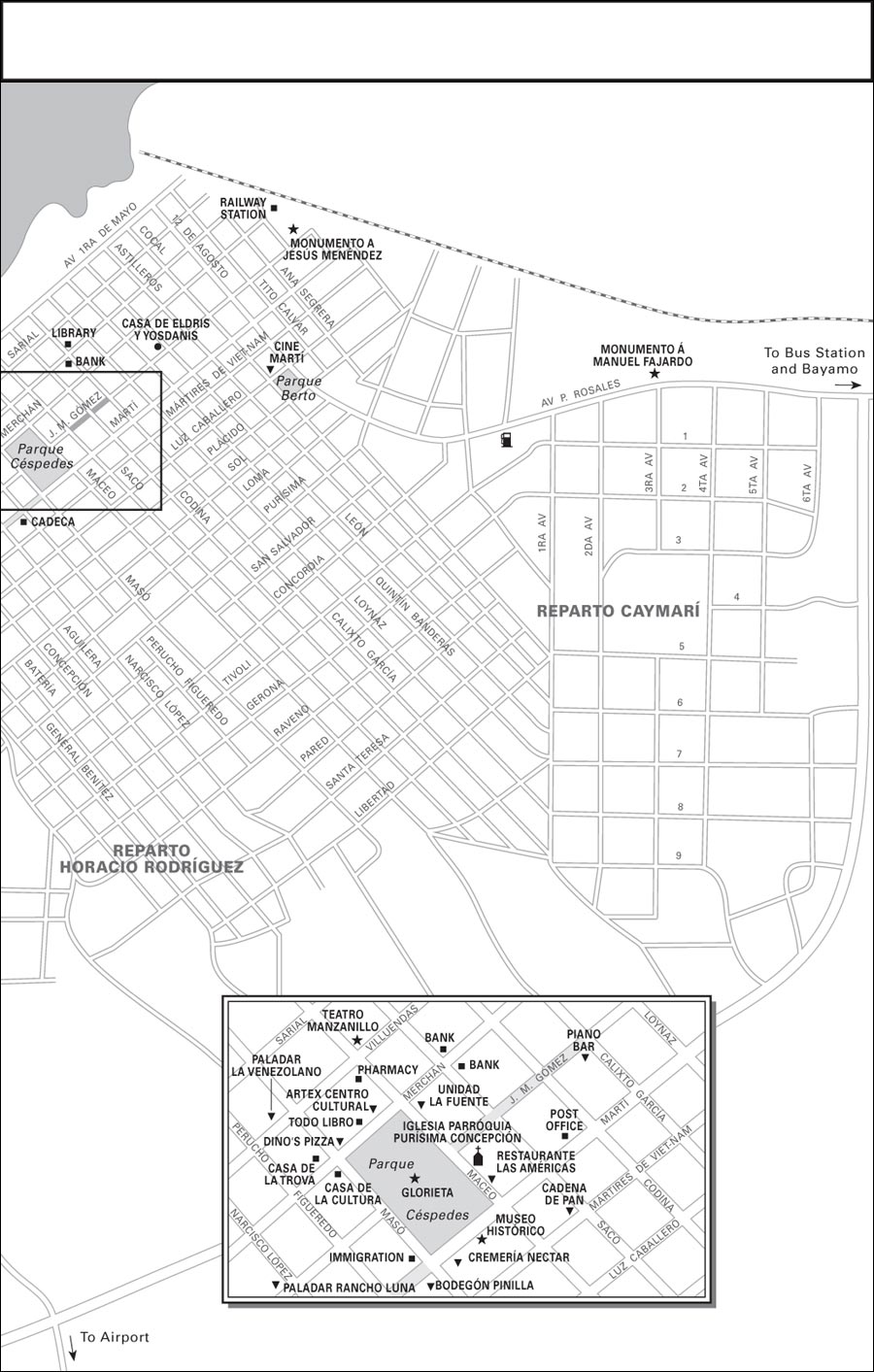

Manzanillo (pop. 105,000) extends along three kilometers of shorefront on the Gulf of Guacanayabo. In colonial days, it was a smuggling port and center of slave trading. Later the once-wealthy city became the main underground base for Castro’s rebel army in the late 1950s (Celia Sánchez coordinated the secret supply routes, under the noses of Batista’s spies). Today the weatherworn town functions as a fishing port. Many buildings have been influenced by Moorish design, but once-glorious buildings are crumbling to ruin. In Barrio de Oro, the cobbled streets are lined with rickety wooden houses with cactus growing between the faded roof tiles.

The Malecón seafront boulevard features a life-size bronze statue of Cuban crooner Benny Moré plus various naked mermaids and maidens. Offshore, the easternmost cays of the Jardines de la Reina archipelago float on the horizon.

Warning: Cholera broke out here in 2012. No wonder! Half the streets have leaking sewers and pestilential standing water.

The road from Bayamo enters Manzanillo from the east as Avenida Rosales, which runs west to the shore, fronted by Avenida 1 de Mayo and the Malecón and paralleled five blocks inland by Avenida Martí. These roads run west to Avenida Jesús Menéndez. The old city lies within this quadrangle.

To the east of the city Avenida Camilo Cienfuegos (the circunvalación) runs south from Avenida Rosales, intersects Avenida Jesús Menéndez, and drops to the Malecón.

City life revolves around this handsome square bounded by Martí, Maceo, Merchan, and Masó. The square has little stone sphinxes at each corner and is ringed by royal palms and Victorian-era lampposts. The most notable feature is an Islamic-style glorieta (bandstand) inlaid with cloisonné.

The 19th-century Iglesia Parroquia Purísima Concepción, on the north side, has a beautiful barrel-vaulted ceiling and elaborate gilt altar.

The Casa de la Cultura (Masó #82, tel. 023/57-4210, daily 8am-6pm, free), on the south side, is an impressive colonial building with mosaics of Columbus’s landing and Don Quixote tilting at windmills.

On the east side of the square, the Museo Histórico (Martí #226, tel. 023/57-2053, Tues.-Fri. 9am-5pm, Sat.-Sun. 9am-noon and 6pm-10pm, free) displays cannons and antiques.

Worth a peek, too, the restored Teatro Manzanillo (Villuendas, esq. Maceo, tel. 023/57-2973), dates to 1856.

Moorish building at Parque Céspedes

Manzanillo’s main attraction takes up two entire blocks along Caridad (e/ Martí y Luz Caballero), where a terra-cotta tile staircase is graced to each side with ceramic murals. At the top is the monument to Celia Manduley Sánchez and a tiny room with portraits and personal effects (Mon.-Fri. 8am-noon and 2pm-6pm, Sat. 8am-noon, free) dedicated to the memory of “La más hermosa y autóctona flor de la Revolución” (the most beautiful native flower of the Revolution).

The Plaza de la Revolución (Av. Camilo Cienfuegos) has a bas-relief mural of Celia Sánchez and other revolutionary heroes.

The town hosts a carnival in August.

The Casa de la Cultura (tel. 023/57-4210) and Casa de la Trova (Merchan #213, esq. Masó, tel. 023/57-5423), both on the main square, host music performances and cultural events.

Piano Bar Mi Manzanillo (J. M. Gómez, esq. Calixto García, tel. 023/57-5312, Tues.-Sun. noon-midnight, free) applies a dress code. A quartet plays jazz, música filin, and even salsa. Music videos and live music draw young adults to Artex Centro Cultural (Wed.-Mon. noon-midnight), on the north side of the plaza.

The endearing open-air cabaret espectáculo at Costa Azul (Av. 1ra de Mayo, esq. Narciso López, tel. 023/57-3158, Fri.-Sun. 10pm, CUC1) is followed by a disco. The bar is in a ship hauled ashore. Friday-Sunday it competes with the Centro Nocturno Los Delfines in the Hotel Guacanayabo (Av. Camilo Cienfuegos, 10 pesos per couple).

Teatro Manzanillo (Villuendas, esq. Maceo, tel. 023/57-2973, 5 pesos) hosts cultural programs.

Baseball games are hosted October-May at Estadio Wilfredo Pages, off Avenida Céspedes.

The stand-out casa particulare is S Casa de Adrian y Tonia (Mártires de Vietnam #49, esq. Caridad, tel. 023/57-3028, CUC20-25), a delightful house with a nice TV lounge with rockers and a balcony overlooking the stairs to the Monumento Celia Sánchez. The owners rent a splendid independent, cross-ventilated, air-conditioned apartment upstairs with fans and a modern bathroom plus roof terrace with an arbor.

You get a spacious, nicely furnished, air-conditioned upstairs room at Casa de Eldris y Yosdanis (Miguel Gómez #347, esq. León, tel. 023/57-2392, nayabo1@yahoo.com, CUC15-25). The hostess is a delight.

Islazul’s Hotel Guacanayabo (Av. Camilo Cienfuegos, tel. 023/57-4012, CUC24 s, CUC33 d low season, CUC25 s, CUC40 d high season, including breakfast) has 108 uninspired rooms, and hot water is only available 6am-9am and 6pm-10pm. At least you get satellite TV, modern bathrooms, a swimming pool, and services. Noise from the disco reverberates on weekends.

The town has few paladares. The best is Paladar Rancho Luna (Calle José Miguel Gómez #169, e/ Narciso López y Aguilera, tel. 023/57-3858), a huge and airy restaurant with lofty ceiling, wrought-iron furnishings, and natural stone walls. It specializes in criolla seafood. Service can be excruciatingly slow.

I enjoyed a delicious garlic seafood plate (CUC7) at Paladar La Roca (Mártires de Vietnam #68, e/ Benítex and Caridad, c/o Adrian tel. 023/57-3028, daily 24 hours).

The most elegant state option is Restaurant La Catalana (Martí, esq. Narciso López, no tel., daily noon-2pm and 6pm-10pm), serving shrimp cocktail, garbanzo, paella, and criolla dishes in pesos.

Fancy pizza? Head to the air-conditioned Dino’s Pizza (daily 10am-10pm), on the north side of Parque Céspedes.

It’s a pleasure to sit beneath shade canopies at Unidad La Fuente (no tel., 24 hours), an ice creamery on the plaza’s northwest corner; on the northeast corner is Cremería El Nectar (Martí, esq. Maceo, daily 10am-10pm), selling four scoops for a mere 2.80 pesos.

You can buy fresh produce at the mercado agropecuario (Martí, e/ Batería y Concepción, daily 6am-5pm).

The post office is on Martí (e/ Saco y Codina). Etecsa (Gómez, esq. Codina) has Internet and international phone service.

Banks include Bandec (Merchan, esq. Codina) and Banco Popular (Merchan, esq. Codina, and Merchan, esq. Calixto). You can also change foreign currency at Cadeca (Martí #184, e/ Figueredo y Narciso López).

Hospital Celia Sánchez (Circunvalación y Av. Jesús Menéndez, tel. 023/57-4011) is on the west side of town.

The police station is on Villuendas (e/ Aguilera y Concepción).

Iglesia Parroquia Purisima Concepción

The Aeropuerto Sierra Maestra (tel. 023/57-7401) is 10 kilometers southeast of town. Cubana (tel. 023/57-4984) flies to Manzanillo from Havana.

The bus terminal (Av. Rosales, tel. 023/57-3404) is two kilometers east of town. Víazul buses do not serve Manzanillo.

The railway station (tel. 023/57-2195) is at the far north end of Avenida Merchan. Trains link Manzanillo with Bayamo (CUC1.70) and Havana (CUC28).

You can rent a car from Havanautos (tel. 023/57-7737) at the Hotel Guacanayabo (Av. Camilo Cienfuegos). There’s a gas station on Avenida Rosales (esq. Av. 1ra) and another on the circunvalación (esq. Jesús Menéndez).

Cubataxi (tel. 023/57-4782) has taxis.

The coastal plains south of Manzanillo are awash in lime-green sugarcane. Five kilometers south of Manzanillo you’ll pass a turnoff for the Criadero de Cocodrilos (tel. 023/57-8606, Mon.-Sat. 7am-4pm, CUC5 including guide), a crocodile farm with more than 8,000 American crocodiles in algae-filled ponds; 1pm-2pm is feeding time. Tip the guide.

baby crocodiles at Criadero Cocodrilos, near Manzanillo

Reaching the sugar-processing town of Media Luna, 50 kilometers southwest of Manzanillo, divert to view the Museo Celia Sánchez (Av. Podio #11, tel. 023/59-3466, Tues.-Sun. 9am-5pm, CUC5, guide CUC5, camera CUC5), in a simple green-and-white gingerbread wooden house where revolutionary heroine Celia Sánchez was born on May 9, 1920. Media Luna’s town park has a fountain with a statue of Celia Sánchez sitting atop rocks with her shoeless feet in the trickling water.

Cinco Palmas, 27 kilometers southeast of Media Luna, has a museum (in a bohío replicating the simple home of peasant farmer Cresencio Pérez) honoring the site where the survivors of the Granma landing linked up.

Niquero, about 60 kilometers southwest of Manzanillo, is unique for its ramshackle buildings in French-colonial style, lending it a similarity to parts of New Orleans and Key West. The Communist Party headquarters, one block from the main square, is in a fabulous art nouveau building.

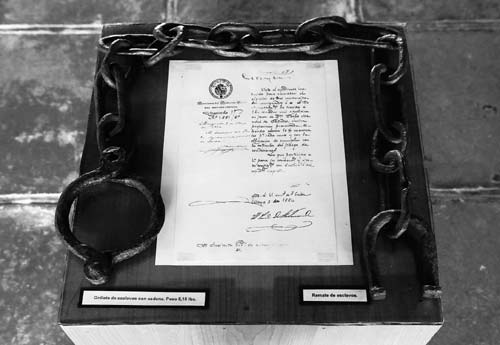

La Demajagua, 13 kilometers south of Manzanillo, was the sugar estate owned by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, the nationalist revolutionary who on October 10, 1868, unilaterally freed his slaves and called for rebellion against Spain. His house (of which only the original floor remains) is now the Museo Histórico La Demajagua (tel. 5219-4080, Tues.-Sat. 8am-5pm, Sun. 8am-1pm, CUC1, camera CUC5, guide CUC5), with eclectic displays that include period weaponry.

slave shackles and Carlos M. Céspedes’s declaration freeing slaves, Museo Histórico La Demajagua

A path leads to a monument of fieldstone in a walled amphitheater encircling remnants of the original sugar mill. Inset in the wall is La Demajagua bell, the Cuban equivalent of the American Liberty Bell, which Céspedes rang to mark the opening of the 1868 Ten Years War.

Islazul’s pleasant Hotel Niquero (Calle Martí, esq. Céspedes, tel. 023/59-2367, caridad@hotelnq.co.cu, CUC18 s, CUC28 d year-round), on the main street of Niquero, offers 26 rooms with satellite TV and modern bathrooms; some have king beds. It has an appealing restaurant (daily 7am-9:45am, noon-2:45pm, 7pm-9:45pm).

This UNESCO World Heritage Site, one kilometer south of the hamlet of Las Colorados, about 20 kilometers south of Niquero, protects the southwesternmost tip of Cuba, from Cabo Cruz to Punta Hicacos. The land stair-steps toward the Sierra Maestra in a series of marine terraces left high and dry over the eons. More than 80 percent of the park is covered by virgin woodland. Flora and fauna species are distinct. Drier areas preserve cacti more than 400 years old. Two endemic species of note are the blue-headed quail dove and the Cuban Amazon butterfly. Even endangered manatees inhabit the coastal lagoons.

The entrance station (tel. 5219-0004 c/o Belic) has a visitor center with exhibits; pay your park entrance (CUC5) here. Beyond, two trails are signed on the road. The Sendero Morlotte-Fustete leads to cavern systems. The more popular Sendero Arqueológico Natural El Guafe, about eight kilometers south of the entrance, also leads through mangroves and scrub to caverns containing dripstone formations. One—the Idolo del Agua—is thought to have been shaped by pre-Columbian Taínos. You can hire guides (CUC5) or hike solo. EcoTur (tel. 023/42-4875 or 07/641-0306, www.ecoturcuba.co.cu) offers guided hikes.

The park is named for the spot where Fidel and his band of 79 revolutionaries came ashore at Playa las Coloradas on December 2, 1956. The exact spot where the Granma ran aground is one kilometer south of Las Colorados. Here, the Monumento de Desembarcadero consists of a replica of the Granma and a tiny museum (entrance is overpriced at CUC5) with a few photos, rifles, and a map showing the route of the desembarcaderos into the Sierra Maestra.

A concrete pathway leads 1.8 kilometers through the mangroves to the exact spot where the Granma bogged down.

The potholed road south from Las Colorados dips and rises through dense scrubland, twists around Laguna Guafes, and ends at the fishing hamlet of Cabo Cruz, the southwesterly tip of Cuba. The Faro Cabo Cruz lighthouse (off-limits; it’s a military zone), built in 1871, rises 33 meters above a shrimp farm.

fishing boats at Cabo Cruz

A plaque atop the cliff states that Christopher Columbus arrived here in May 1494.

Restaurante El Cabo (tel. 023/90-1317, daily noon-2:30pm, 3pm-5:30pm, and 6pm-9:40pm) offers seafood beside the lighthouse in Cabo Cruz.

From Entronque Pilón, five kilometers north of Niquero, a scenic road cuts east through the foothills of the Sierra Maestra and drops down through a narrow pass to emerge on the coastal plains near Pilón, where a gas station is the last before Santiago de Cuba, 200 kilometers to the east.

The flyblown fishing (and, until recently, sugar-processing) town of Pilón is ringed on three sides by mountains and on the fourth by the Caribbean Sea. The land west of Pilón is smothered in sugarcane. East of Pilón, the land lies in the rain shadow of the Sierra Maestra and is virtually desert. Cacti appear, and goats graze hungrily amid stony pastures. The town’s sole attraction is Casa Museo Celia Sánchez (Conrado Benitez #20, tel. 023/59-4107, Tues.-Fri. 8am-noon and 1:30pm-5:30pm, Sat 8am-noon, free), a beautiful red-and-yellow clapboard house once used by Celia Sánchez as a base for her underground supply network for Castro’s rebel army. It’s a museum dedicated to the revolutionary underground and literacy campaign.

Fifteen kilometers east of Pilón the mountains shelve gently to a wide bay at Marea del Portillo, rimmed by a beach of pebbly gray-brown sand. Marea del Portillo is favored by budget-minded Canadian and European charter groups, but facilities are limited to the two resorts and you’re out on a land-locked limb.

Water sports and scuba diving (CUC30) are offered at Marlin Albacora Dive Center (tel. 023/59-7139), at Club Amigo Marea del Portillo. Dive sites include the wreck of the Cristóbal Colón, a Spanish warship sunk in the war of 1898.

Excursions include horseback rides (from CUC5), a “seafari” with snorkeling at Cayo Blanco, city tours of Bayamo, and hiking to La Comandancia de la Plata.

Cubanacán operates three hotels at Marea del Portillo. Villa Punta Piedra (tel. 023/59-7062, CUC14 s, CUC2 low season, CUC28 s, CUC40 d high season, including breakfast), five kilometers west of Marea, recently spruced up and has 13 spacious, simply furnished air-conditioned villas, plus a restaurant and bar.

The all-inclusive beachfront Club Amigo Marea del Portillo (tel. 023/59-7102, reservas@marea.co.cu, from CUC42 s, CUC64 d) is divided into a beachfront property and a much nicer hilltop facility, 600 meters apart. Together they have 283 rooms and suites, including 56 cabinas. Each section has a restaurant, bar, and swimming pool. A simple cabaret is offered, and the hilltop option has a disco, but the constant need to walk between the hotels soon grows old.

For a meal with a view, head to the elegant Restaurant El Mirador (tel. 5269-0599, daily noon-9pm), on a hillside two kilometers west of Villa Punta Piedra.

A camión runs between Pilón and Santiago de Cuba on alternate days.

You can rent cars and scooters at the Club Amigo properties through Cubacar (tel. 023/59-7185). Horse-drawn coches charge CUC3 for a tour of the nearby fishing village.

A rugged mountain road links Bartolomé Masó and Marea del Portillo; a jeep is required.

The rugged coast that links Marea del Portillo and Santiago de Cuba is an exhilarating drive. The paved but dangerously deteriorated road hugs the coast the whole way, climbing over steep headlands and dropping through river valleys. The teal blue sea is your constant companion, with the Sierra Maestra pushing up close on the other side. There are no villages or habitations for miles, and no services whatsoever. Landslides occasionally block the road, much of which has been washed away; near La Cueva you have to run along the shingle beach. It may be impassable at high tide and in storms. A jeep is essential.

In springtime, giant land crabs march across the road in fulfillment of the mating urge. Amazingly, the battalions even scale vertical cliffs.

The dangerous derelict bridge over the Río Macio, 15 kilometers from Marea, marks the border with Santiago de Cuba Province. Ford the river instead.