The best way to deliver information is by first understanding your listening environment and then telling a story.

—RUSS CHARLTON,

former vice president of internal auditing at Time Warner

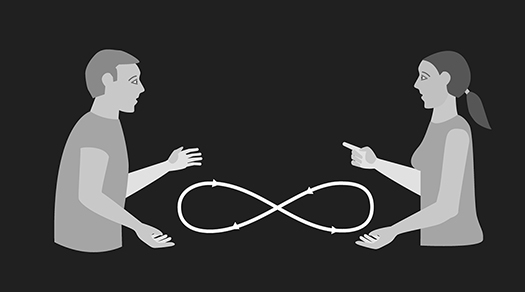

If we were in a Narativ training together right now, your listening would be creating my speaking, and my speaking would be creating your listening. We would have already entered into a feedback loop with one another even though we barely knew each other. Telling shapes listening. Listening shapes telling. The feedback loop we are describing is, according to the Narativ method, precisely what transformed communication actually looks like: it’s when you pay heed to the reciprocal relationship between listening and telling.

When we say there is a reciprocal relationship between listening and telling, we mean that they are mutually influential. Speaking and listening influence each other throughout any conversation or presentation. Any shift in one creates a shift in the other. As we seek to connect with our audience—and to maintain that connection—being sensitive to this natural dynamic is essential (see Figure 2.1).

FIGURE 2.1 Reciprocal Relationship Between Listening and Telling

What impedes this flow are what we call in Narativ parlance “obstacles to listening.” As noted earlier, we prioritize listening in our method. Therefore, for successful communication to take place in the time and space we’ve allocated for it, we should identify and release any obstacles to listening so that they don’t affect the telling.

Russ Charlton, the former VP of internal auditing at Time Warner, who brought in Narativ to Time Warner to address the blockages to listening and telling, told us about his experience of the importance of listening:

I remember your saying to be aware of what’s going on around you. That really stuck with me. Just sitting here now, there are people having normal conversations over breakfast, noises from the kitchen, the clanking of plates. Every time a car goes by, there’s a distracting reflection on the wall behind me. I have to be aware of the listening environment to know whether you and I are making a connection and adjust to that.

Do I need to raise or lower my voice? Should I lean in closer? All those things were a vital part of training our auditors on how to be better listeners and better communicators. If I want to engage deeply with a human resources manager or an employee who has a personal matter, I turn over my phone and push it away so that I can fully engage with the individual. Then the first thing you do is close your mouth and listen to what people are telling you because you are going to interview people about their area of expertise. I’m not a cloud computer expert or a data privacy expert, and neither are the people on my team, but the people we are interviewing should be, and so we go in and listen to them. To be able to tell an effective story, first you have to be able to listen.

Listening may be likened to a container, and story may be likened to the liquid that is poured into the container. The container gives shape to the liquid in the same way that the listening gives shape to the story (see Figure 2.2). This may seem obvious, but it is experientially profound. Pay attention to it in your next conversation.

FIGURE 2.2 Listening Is the Container that Gives Shape to the Telling

This recognition of the reciprocal relationship between listening and telling becomes a lens through which to examine the communication environment in any organization. When Narativ goes into companies to address communication issues, we first look for what gets in the way of that dynamic. What gets in the way of listening? What’s shaping the telling? If, for example, team members prioritize competition over collaboration, as we discovered they were at a large social media company, then competition is setting the tone of the communication. What is it like to tell stories in a competitive environment? What happens to your listening? At Narativ we consider this first stage of our communication assessment as ethnographic: we are looking at the culture of an organization or department broadly to determine trends in communication obstacles.

Let’s explore how first we identify obstacles to listening and then how we release those obstacles in a real-world example. The end goal is always clear communication. With clear communication, any objective can be achieved.

IDENTIFYING THE OBSTACLES TO LISTENING

Narativ was invited to present our listening and storytelling method to 14 global marketing teams at a social media company. The leaders of the marketing group wanted us to focus entirely on listening because they felt that storytelling was already so much a part of the company’s DNA. Although this example appears to address only listening, you will quickly see how listening and telling never live apart. We heard from managers at this company, “Everyone’s talking, everyone’s telling stories, but our teams are not listening to each other. How do we help them listen and therefore collaborate better?” I appreciated their conundrum and the way they approached it. In our work with technology companies in the midst of rapid growth, I’ve often observed a recognition of the importance of empathy in interpersonal relationships as a means to evolve communication. This, of course, has everything to do with listening and telling.

People who work at large technology companies are often single-minded, ambitious, and competitive. Although these qualities are syntonic with the company’s driven corporate culture, they do not align with the aspiration for staff to support one another’s successes and thereby foster stronger bonds within the team. In fact, there’s a tendency to blame others when things go wrong, which leads to conflict, resentment, and breakdowns in mutual understanding. Employees talk over one another or attempt to dominate in conversations and meetings. The core problem is that people lose touch with the fact that collaboration and communication depend on listening.

Employee engagement surveys conducted before we visited verified that communication and transparency are the two most challenging areas in the culture of this social media company. Whereas a fast-paced, multitasking approach is often seen as a virtue at technology companies, the marketing leaders had identified a need to develop mutual understanding and empathy in the communication styles of their teams. The challenge was to transform current conversation modalities so that members of the 14 marketing teams, each dealing with a different audience, would be motivated to support one another toward the achievement of shared performance goals. This included identifying and addressing personal and cultural obstacles to listening and building a skill set to move members away from disconnection toward empathy. We provided a hands-on, experiential approach to identifying obstacles to listening at the company’s campus in California.

Let me drop you into the training to demonstrate how obstacles to listening may be identified in the moment-to-moment of communication. As I always do, I began with my AIDS Program story followed by a brief Listening Contemplation exercise. This contemplation asked people to become aware of their immediate surroundings and then progressively to move to introspection, simply noticing when obstacles emerged throughout. Let’s start with that contemplation, which is usually done with eyes closed.

Listening Contemplation Exercise

After guiding the audience through this contemplation, I reached out for feedback. If you want to know what obstacles to listening are in your audience, the best way to find out is to ask them:

“I was trying very hard not to think about my phone in my pocket.”

“I became irritated when I heard paper crinkling.”

“I couldn’t get my to-do list out of my head.”

“I hear my baby crying even though I’m across the country.”

“I felt super connected to you while recalling my own memories of people from that time.”

“I kept going back to past experiences habitually each morning, so I was replaying those in my mind and then losing my focus.”

“I felt a lot of irritation in my body as I slowed down and tried to pay attention to the exercise.”

These responses are revealing of common obstacles people encounter in the work environment. Other obstacles can be more subtle and difficult to identify.

Alex, a participant in the training, shared that he was having a hard time listening because my presentation seemed a little “goofy.” I wasn’t sure what he meant by that, so I asked him to explain.

“Like, I can’t take you seriously. This cynical side of me takes over. I wonder if I’m just being manipulated. I’ve got opinions on how presentations should be, and I’m judging you.”

The ability to truly hear others’ obstacles requires listening without judgment, opinion, and rationalization. Rather than penetrating Alex’s judgment, arguing with him or being defensive, which would most likely throw fuel onto the fire and make his opinions even stronger, instead, I thanked Alex for his honesty, and I let him know that I had heard what he’d said: that he’d judged me and had thought, “I can’t listen to this guy because what he’s saying sounds goofy and manipulative.”

Imagine if I had taken Alex’s comment personally and had felt insulted or humiliated. I could have retorted that there is a thorough scientific basis to my methods and that they’d worked successfully with thousands of others in the technology field. That would have been just me defending myself—and not listening to him.

I would like to make special note here that the statement “I hear you” has been co-opted into corporate parlance to a certain degree as a way of shutting people up. In our method, if you don’t mean it, don’t say it. In that way, the listening of both parties is genuine and flows freely.

Alex responded, “What would you suggest I do to circumvent that sort of continued cynicism because it shows up in my work all the time? How do I get to a place of positivity, of being open, when things are not necessarily what I would initially connect to?”

Here’s the opening for Alex to notice his tendency to make judgments and close down. In the Narativ method we’re acutely aware that trying to push these thoughts away is like feeding them Miracle-Gro. They’ll just get stronger. In other words, don’t judge your own judgment. Just be aware of it and observe it.

I suggested Alex try a different tack and simply note, “There goes my mind again, doing that same old judging thing.” To take it a little further, I suggested he ask himself, “What am I gaining by having that kind of judgment? What am I losing by having that kind of judgment?” What he gains is a sense of superiority and separateness. He holds himself apart. What he loses is a sense of connection with himself and with others. He loses the opportunity of understanding.

By simply asking what the obstacles were, we unveiled the power that judgment has to interfere. We added it to our growing list on the room’s whiteboard. “Sounds, to-do lists, body irritation, judgment.” Next, let’s look at technology itself as an obstacle to listening.

TECHNOLOGY: A DEEP DIVE

“Even though I had it on silent, it was buzzing and vibrating.”

At the most obvious level, Kareem’s phone is an external obstacle—that is, an outside force that affects his listening. However, it also operates on a physical level, vibrating against his thigh. Many recent studies also show how device sounds and alarms produce a stress reaction in the body.1

Kareem tells us that he’s trying hard not to think about his phone. Not only is this thought an additional obstacle to listening but so is the feeling or emotion associated with the thought. I ask him about that. He says, “It’s all about the to-do list, being in control. I’m constantly worried about all this stuff that needs to get done, running out of time, not getting to deadlines, and disappointing people.”

When I push him to go deeper, Kareem tells me that his concern is ultimately about self-preservation and survival and that if he’s really honest with himself, he’s in a constant state of fear.

Kareem is not alone. So much of what drives obstacles to listening is fear on a primitive and visceral level—that worry, that anxiety, that sense of “what’s going to happen if I ignore my phone?” It serves us tremendously well to be able to identify the obstacle of fear in our own listening because so many times our knee-jerk reactions to things are based on unacknowledged fear. Instead of recognizing the fear in ourselves, we project it onto someone or something else.

“So you worry about being in trouble then?” I ask Kareem. “Is there a power dimension as well?”

He responds, “Ultimately, yes, the fear is ‘you’ll be in trouble,’ that someone’s going to see what you’ve done, and there’ll be repercussions.”

I thank him for his honesty and for revealing this insecurity. His statement corroborates our own findings that a tremendous obstacle to listening is relational power dynamics.

This simple group exercise revealed all kinds of obstacles to listening. They had mainly to do with the mind’s constant chatter or physical discomforts. But there are psychological (emotional) obstacles to listening too, such as longing, memories, and loss. And as we saw with Kareem, there are relational obstacles to listening, such as power: Who is speaking, and are we listening to them from a place of powerlessness or fear? Has something transpired in the past that fills our listening with criticism or judgment? We may feel justified in our stance based on past experiences or other habitual emotions (for example, “I’m someone who’s just uncomfortable in meetings”), but these create a stumbling block to our productivity. Even obstacles that are not personal, that are part of a corporate culture, can be noticed and related to.

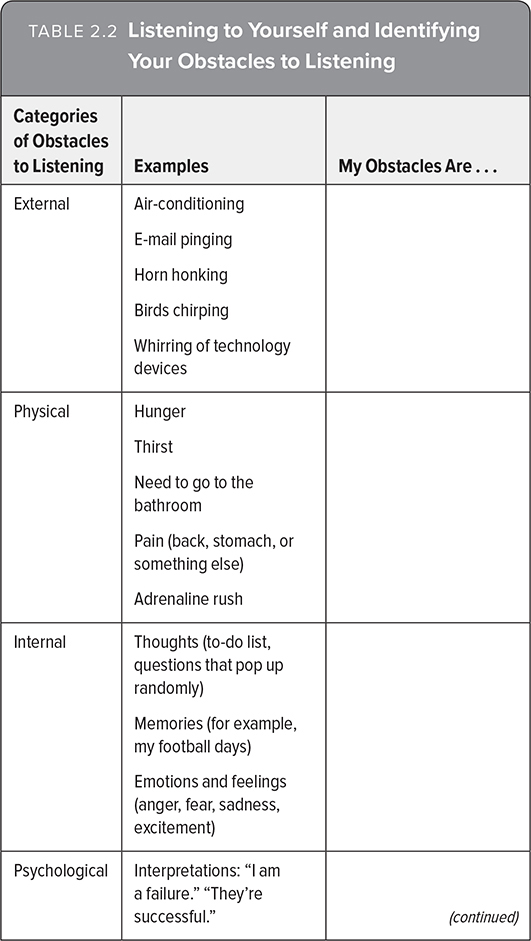

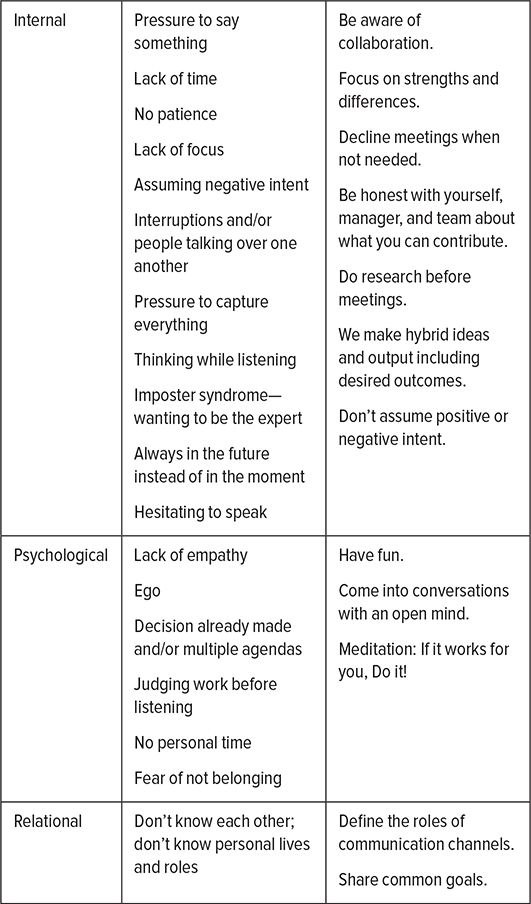

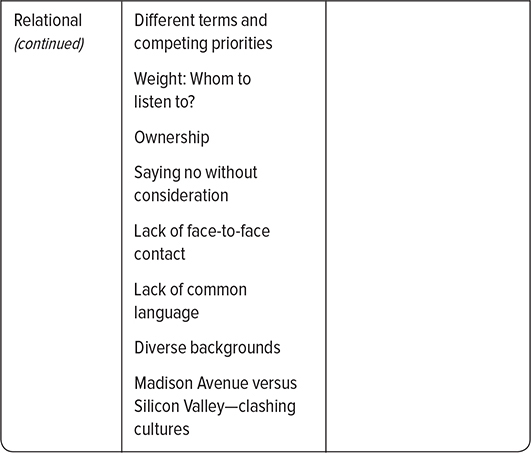

In Table 2.1, let’s look at the array of obstacles to listening the teams identified during breakout groups and how they sought to address them.

Open listening takes a leap of trust. Through their willingness to listen to one another, team members demonstrated that they were able to place principles ahead of personalities and to suspend emotional reactivity in the service of the well-being of the team and its goals.

However many obstacles reveal themselves in a listening contemplation or group check-in, in our method we take the position that there is nothing wrong with the obstacles to listening. They just are. We notice them. In fact, just to notice them sometimes takes real self-awareness. Simple-seeming obstacles can be tied to deeper fears and undercurrents that run within a company. These are things that have become embedded in an organization’s culture, and they should be identified and acknowledged. The number of obstacles to listening of which we’re not usually aware is surprising. Open listening challenges our habits of ignoring. It requires a commitment to go beyond all those obstacles, to keep them out of the listening space. Finally, identifying the obstacles helps us give the gift of listening.

The Narativ method, unlike many storytelling techniques, seeks to understand a business’s specific culture or a team’s working atmosphere, “the listening environment,” as the platform for change. As an individual in a company’s culture, your listening is the lightning rod for those obstacles, allowing you to identify and then release them, as we will discuss in the next chapter.

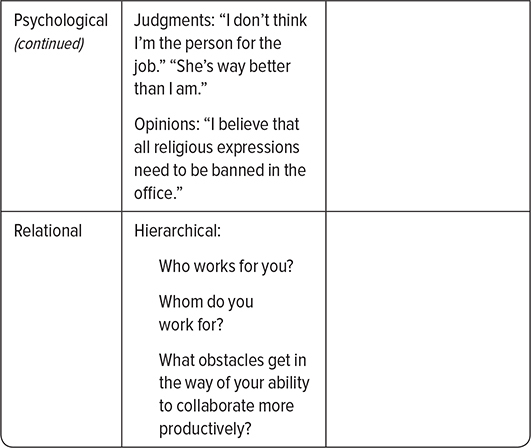

CATEGORIES OF OBSTACLES TO LISTENING

As a guideline to approach the listening environment in your organization, we’ve provided the following five categories. They form the core of our ethnographic approach, and you’ll be reading more about them as the book progresses. Narativ’s cofounder, Paul Browde, MD, helped develop this list in the early days of our method.

We have made an exhaustive categorization of obstacles to listening because it’s the awareness of them that gets the process of releasing them started. So much is swept under the rug in ordinary communication. To be resilient, present communicators, alive to the reciprocal relationship between listening and telling, we need to clearly understand all types of obstacles that present themselves. This kind of expertise is a communication skill we benefit from developing.

External Obstacles

Hearing is the physical perception of sound, in which sound waves are received by the eardrum and then, through a complex set of mechanical interactions involving very small bones, are translated into nerve impulses that travel to the brain, where they are interpreted into meaning. Hearing is one component of listening. As the sound and tone of the words enter the body, they cause a wide range of effects. The quality of the sound of a voice can cause feelings in the body. Some voices are musical and soothing, whereas others are harsh and unsettling. Notice how the sound of a voice can alter your breathing. Some voices cause you to take deep, slow breaths, resulting in a wave of relaxation through your body. Other voices cause you to take short, sharp breaths, resulting in a level of anxiety and perhaps irritation.

Other hearing obstacles to listening include the most obvious ones—noises and other sounds, such as traffic, barking dogs, jackhammers, music, or whirring air conditioners. This also includes an excessively loud voice. How can you possibly listen to what someone is saying if he or she is trying to command your attention by yelling or shouting? All you can hear is the shouting.

Seeing is the physical perception of visual stimulus through the eyes, in which images are perceived and communicated to the brain for interpretation. How does what you are seeing affect your ability to listen? If the storyteller looks sad, does that increase the level of attention you bring to his or her speaking? Does it decrease it? If somebody looks disheveled and unkempt, are you likely to listen with the same degree of attention as you would if that person were neatly dressed in an expensive suit? What judgments arise from seeing?

Smelling is the physical perception of olfactory stimulus through the nose and into the brain. How does the smell in the room affect your ability to listen? Does a strong perfume or scented candle interfere with your concentration? Does the smell of a crackling fire in the hearth induce a feeling of coziness and comfort, allowing greater listening?

Physical Obstacles

These most often have to do with the body’s physical needs: hunger, needing to go to the bathroom, tiredness, physical discomfort or pain, sexual arousal, clothing that’s too tight or uncomfortable, rashes, feeling sick, or even having a bad hair day!

Internal Obstacles

Internal obstacles include thoughts, memories, emotions, and feelings. You can have a variety of feelings in an hour, even within a minute, especially if you are upset or sad, or feel extreme happiness or joy. These can be obstacles to listening. Some of these obstacles are invisible to others and often to ourselves.

We use the general term noise to refer to the constant chatter that is going on in our minds. This noise consists mostly of free-floating thoughts that vary in intensity and may include shopping lists, ruminating over a recent argument, or obsessive preoccupations. “Did I turn off the stove?” “Did I pay the phone bill?” “I wish I could get that song out of my head!”

Psychological Obstacles

Judgments of others and ourselves make it difficult to listen and be creative. “I am not good enough.” “He is better than I am.” “She doesn’t know how to tell a story.” Opinions or strong beliefs of agreement or disagreement can interfere if the listener likes or dislikes what the storyteller is saying. Opinions about religion, politics, or other topics may be obstacles to listening.

Interpretations refers to the meanings we create about others or ourselves. “I am a failure” is an example of meaning attributed to a particular set of life circumstances. It is difficult to tell an empowering story with this interpretation.

Similarly, when a listener interprets the life of the storyteller, it limits the ability of the latter to create freely. If we think, “This manager is a disaster, and he is clearly still under the influence of the person he replaced,” we inadvertently may be creating that story in the teller. Even if you think the interpretation is kind, it interferes with listening. Avoid bringing your own analysis or caretaking to someone else’s story. Judgments of others and ourselves make it difficult to be generative and creative.

Relational Obstacles

The relationships we have with people often shape the way we listen to them. Usually, one person is in a more powerful position than the other. The way you listen to your parents or siblings is different from the way you listen to a police officer who pulls you over for speeding or your doctor who calls you in to discuss the results of a test. We’ve all seen how a son listens to his father giving advice after a soccer game or a young girl looks up to her grandmother. Imagine different people telling you the same information—see how each relationship influences how you hear what’s being said. At work, there is a hierarchy, and that’s a natural and important structure. Bringing awareness to how the hierarchy affects our listening is crucial so that we don’t let it influence open listening. This is not to dismiss or undermine necessary power structures but simply to be aware of how our ideas about them affect what we hear. Otherwise, we may not contribute all that we can, or conversely, we may not allow our leaders or subordinates to contribute their best.

• • •

Understanding what blocks us from listening to ourselves and to others is fundamental to the Narativ method. You will not receive the benefits of the method unless you fully understand and implement the basic concept that there is a reciprocal relationship between listening and storytelling. My listening must be clear for me to be present with you, and your listening must be clear for you to be present with me. We have a lot of power as listeners. Use it well!

Once we’ve identified these obstacles, we intend to let them go. That is essential to our method. When we want to listen, it is not the time to address or hold on to any obstacles. It is the time to release them in favor of listening and participating. We can always get back to our to-do list or take up more challenging interpersonal conversations later. We can incorporate what comes to us into an inventory of observations to use to address larger issues. But when it comes to listening and storytelling—the immediate act of communication we seek to accomplish through our method—we let go of obstacles to listening. This, like everything in our method, takes practice. We’re unlearning old habits and activating potential. To listen without judgment in particular is surprisingly difficult, but the more you do it, the more you—and your team—will reap the rewards.

BEING YOUR OWN BEST LISTENER

At Narativ, we always say, “Listening begins with you.” This may seem ironic after we’ve put so much emphasis on the reciprocal relationship of listening and telling. But in a sense, it is the most powerful key to successful communication, collaboration, and giving mutual support. Learning how to listen to ourselves first will heighten our ability to listen to others (Figure 2.3).

Listening to oneself is a form of introspection. We each have the ability to be reflective of our own story by asking, “What are the obstacles in my listening to the story I’m telling?” For example, if I am to address a sales team, as I imagine them as my audience, what obstacles arise for me? Fear. Discomfort. Is there someone I am attracted to, or do I harbor some resentment toward a coworker? This is all natural, normal, and human, and we make no claim to solve these obstacles with the method. But we recognize that they get in the way of our listening and our performance. So we identify them and let them be rather than suppress them or use other common psychological tactics. In a sense, being aware of them enhances our storytelling because there’s nothing under the rug, nothing hidden holding us back. It takes a little courage to bring forth these obstacles, but that courage creates an open field for our storytelling.

FIGURE 2.3 Listening Begins with You

This type of introspection is not about being preoccupied with ourselves. Even when we are alone, it posits an audience in our listening, and therefore we’re always in a reciprocal mode. It can be enormously helpful to analyze how one is approaching a team by identifying the audience, then the obstacles, and finally, releasing them so you can proceed. Releasing the obstacles is the counterpart to identifying them, and it is the topic of our next chapter.

LISTENING IS THE BEGINNING

Listening is the beginning of the transformation of communication in business. How often do we hear, “They were not listening to me”? How often do we feel the presence of distraction in our exchanges with others? And how much do these experiences reflect deeper trends within our company’s culture that play a role in decreasing productivity and job satisfaction?

We might say that we can change this by simply paying adequate attention, but we need a more compelling understanding of how communication takes place. The reciprocal relationship of listening and telling provides that framework. Within its boundaries, we can use our ears, our entire bodies, and our brain’s incredible abilities to take in information openly and without judgment, knowing that listener and teller play equal roles in the success of the exchange.

So begin paying attention to how you listen and how that affects the telling of your team members. Just as listening starts with you, so does change, and we can all be change agents in our organization when we listen.

LISTENING AND EXCAVATING

When you practice identifying obstacles to listening, you will notice that many of your obstacles have to do with past experiences and memories. One of the reasons we do not suppress the obstacles but just make note of them and let them be is that some of them can be material for our stories. Therefore, identifying obstacles to listening not only paves the way to releasing obstacles but also can potentially lead to identifying an experience or memory that could become a story. So pay attention to your obstacles because your next great story might be hiding in plain sight.

Now, take a moment to listen to yourself and identify your obstacles to listening at this very moment. Use Table 2.2 to categorize your obstacles.