In December of 1993, six months after my dinner with Shirley, I went looking for my father’s birthplace in the French Quarter in New Orleans. Although he was only six when his family left for Brooklyn, in his stories and writings my dad was always offering the French Quarter as a way to explain his upbringing and the kind of man his father had been—a bel homme (beautiful man) and raconteur. It was there that my father’s secret history began.

My boyfriend at the time, a television reporter named Bill, came with me, offering up his skills to help me get the story on my dad. I don’t remember specifically discussing it, but it was understood that Bill and I were trying to find an answer to that first question I’d had on learning my father’s secret: How black was he?

Before we left town, I discovered a copy of my dad’s birth certificate that I’d somehow missed during my childhood snooping. It stated that before the recorder of births, deaths, and marriages for the city of New Orleans had personally appeared

Paul Broyard, native of this city, residing at No. 2444 Lapeyrouse Street who hereby declares that on the sixteenth of this month, (July 16th 1920) at no. 2524 St. Ann Street was born a male child, named Anatole Paul Broyard, Jr. (col), lawful issue of Anatole P. Broyard a native of this city aged 33 years, occupation carpenter and Edna Miller a native of this city aged 25 years.*

I knew from Shirley that Paul Broyard was her and my father’s grandfather. This fact and the addresses on the document were all the information I had to go on.

On a Friday evening, Bill and I checked into a guesthouse on one of the Quarter’s side streets and then headed out to walk around. Tall stucco townhouses painted in pale shades of pink, green, and blue sat flush along the narrow sidewalk. Ornate iron balustrades outlined second-floor balconies and heavy black slatted shutters folded back from windows. We wandered down the roughly laid brick sidewalks and peered behind gates and doors at tucked-away courtyards with small fountains at their centers and bare trellises set against their walls. The scene fit the image of my father’s childhood home that I’d developed from his stories and from what he’d written about the place. Explaining his father’s habit of walking down Broadway every Saturday after the family moved to New York, my father wrote that “every man in the French Quarter was a boulevardier, and life was a musical comedy.” I could imagine his father, who “had a blues song in his blood, a wistful jauntiness he brought with him from New Orleans,” strolling here.

Bill and I made the compulsory trip down Bourbon Street. We passed a jazz band—with a few horns and a drum kit—set up on a street corner and a mime with his face covered in white greasepaint posed motionless on a stepladder under a streetlamp. The shops, still open, displayed rows and rows of Mardi Gras beads, beer mugs with crawfish etched into their glass, and T-shirts that said things like “I’ll show you mine if you show me yours” and “New Orleans/Home of the Big Party.” All the bars had their doors propped open despite the cool December evening, and music bled onto the street: drunken college boys singing off-key karaoke versions of Van Morrison and the steady throb of a disco beat. Every once in a while, we passed standing in a doorway a buxom woman clad in a sequined halter top or a metallic-colored minidress, wrapped in a fake fur stole, and perched on stiletto lace-up boots. She’d be leaning against the doorframe, chatting with the bouncer, his jacket zipped up against the cold, and when we walked by, they’d both pause, and she’d straighten up, switch her weight from foot to foot, throwing a hip out and her chest forward, wondering if the young, adventuresome-looking couple cared to come on inside.

As we walked up to Decatur Street, near the Mississippi River, passing more T-shirt shops and rowdy bars, my mood turned dark. Outside of that one charming street, the musical comedy of my father’s French Quarter with its jaunty walkers and raconteurs had been usurped by this tacky burlesque. I knew that it was unreasonable to expect a neighborhood to remain unchanged after almost seventy years—and of course the city would change more drastically still after Hurricane Katrina—but I’d hoped to feel more kinship to the place, that it would call up the hidden blues song in my own blood rather than a feeling of slight disgust. We paused at Jackson Square, a small, pristine gated park with a statue of Andrew Jackson rearing up on his horse at its center. The park gate was locked, but a few homeless people had spread out their bedding and tucked in for the night. Behind the park loomed St. Louis Cathedral, built in colonial days, a tall and regal remnant of more refined times.

We headed back to our room, walking along one side of the cathedral. When we reached the next cross street, Bill paused and pointed up to the sign. We were on St. Ann, the street where my father was born. We strolled along it for a few blocks, and I noticed some of the same aspects of the town houses that had charmed me earlier. Neither Bill nor I could recall the street number from my dad’s birth certificate, so we decided we’d come back the next afternoon after visiting the library. I could have already passed the house, I thought, imagining my infant father in the arms of his grandfather as he stood in the courtyard and admired his newest descendant, before setting off for the Board of Health to declare the birth.

I was also relieved to note that there was a street named St. Ann in the French Quarter, that at least this detail shared by father about his origins was true.

The most frequent visitors to the Louisiana Division of the New Orleans Public Library are amateur genealogists. You can spot them hunched in front of microfilm readers, searching through reels and reels of census data, city directories, old newspapers, wills, and successions; or lugging armfuls of volumes of church records or reference books back to large wooden tables; or crouched in front of filing cabinets housing index cards listing obituary notices or marriage licenses. Many of them are older retirees, but they speak about their genealogical searches as though they were work: I’m so busy lately—too many meetings, and I still haven’t gotten up to the state archives.

Many plan on publishing the results of their research when it is complete, which is often defined as having traced their family name or group of names back to their countries of origin, with the birth date and place of the first emigrants to America. The stacks of many regional libraries are full of such volumes. The authors sometimes sell them to the general public through genealogical Web sites and newsletters, but most are content to produce a book for their relatives and colleagues, perhaps especially their colleagues.

The researchers lean over the documents for hours, occasionally taking a break to stretch their backs and rest their eyes, and then they are at it again. It is exhausting, tedious work. The historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall spent fifteen years studying microfilmed records throughout Louisiana and in Spain, France, and Texas to create a database containing the largest collection of individual slave records ever assembled. An article about her achievement that appeared on the front page of the New York Times noted that Hall nearly lost her sight in the process.

Now and then you can overhear someone talking to herself: There you are! or Well, lookie here.

Always they are searching for a name—their surname, or their mother’s, or their grandmother’s, or the maiden name of the mother of their great-grandfather. When they find these names, they can begin to lay claim to history. They tell themselves a story: My family has been in this city for over two hundred years. We lived in this neighborhood and on those streets. We were farmers or lawyers. We fixed shoes. We fought in wars. We had money. We knew people who were important. We were important. You’ll find our name in history books. We took part in shaping this time, this place, this world. We mattered. We will not be forgotten.

I envied these people. Whereas they were unraveling a ball of thread that started with family stories and yellowing photos displayed in the hall, my lead was a dusty, tangled thing that had been kicked under the bed years before. Unknotting it wasn’t going to be easy.

After Bill and I spent a few hours before the microfilm readers ourselves, all we had was a handful of seemingly unrelated facts. I’d tackled the obituaries while he looked up census records. In the 1830 New Orleans census appeared a Gilbert Broyard, between the ages of thirty and forty, listed as white, living with two free colored girls and two free colored boys, all under ten years old, and one free colored female between the ages of twenty-four and thirty-five. Until 1860 only the heads of households were named in the census, so there is no way of knowing who these other people were. Did this family represent the beginning of the race-mixing in my father’s tree? That would make his—and my—ancestors black for more than 160 years, more than three times as long as the 50 or so years that my dad had lived as white, and six times as long as the 24 years that I had.

Bill brought over the current New Orleans phone book to show me the dozens of Broyards listed. My family had always been the only ones I knew of, and it was strange to see the name over which I’d felt so proprietary repeated again and again.

“I’ll get a copy of this page so we can start calling people,” he said.

I told him not to bother, that we wouldn’t have time this trip to see anyone. I didn’t tell Bill that I had already run across some Broyards myself in an index of articles appearing in New Orleans newspapers between the eighteenth century and the mid-1960s. I had been thrilled to find numerous entries, until I looked them up and saw that two were references to Broyards who had been arrested—one for immoral behavior with a fourteen-year-old and the other for being caught with $20,000 worth of narcotics—and a third was a guy who’d witnessed a murder. Their names had appeared in the police logs of the paper, which made me hesitant about getting in touch with the rest of my relatives.

Anyway, we had to get going if we wanted to hunt down the house where my father was born. We left the library and, after a quick sandwich, made our way to St. Ann Street and looked for 2524. The block that ran along St. Louis Cathedral was numbered in the 600s; we started walking away from the river, figuring that it couldn’t be too far. The route led us through Louis Armstrong Park, which runs along the edge of the French Quarter proper, and when we got to other side, the street numbered only in the 1500s—and the neighborhood had suddenly, dramatically, declined.

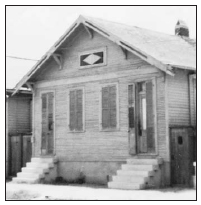

Here and there a few brightly painted wooden cottages remained with their lacy Victorian ornamentations, but most were in need of a paint job and had fallen into disrepair. Tall onion grass grew up around the foundations. Rooflines were pocked with gaps in the slate shingles. A surprising number of lots were empty, with just a square of scorched earth marking where houses had once stood.

Everyone we saw was black and looked poor. A young woman stood in an open doorway and watched us as we walked by. With loose jeans that snagged on her hip bones, she was rail thin. A little girl with holes in the knees of her pants was by her side. When she saw us, she reached for her mother’s hand. On the next block, some teenaged boys stood around a car with the doors opened and the radio blaring. They also turned to stare. We hit the 2000 block; another five to go. I felt as though we had been walking for hours.

For his job Bill sometimes had to travel to Boston’s inner city, knock on strangers’ doors, and ask if they had a photo of the son or daughter who had just been killed or arrested, and if a parent, uncle, or sister would be willing to talk to him for a minute. As we walked down St. Ann Street, he seemed perfectly at ease. He kept commenting on our surroundings, noting an interstate that we had passed under and wondering when it had been erected and about the effect on the neighborhood. He pointed out nice details on houses and speculated about urban renewal programs.

I remember wanting to ask Bill to lower his voice, to stop gesturing at people’s homes, to stop calling so much attention to us, but I was grateful for his company and his interest in my search, and I didn’t want to do anything that might discourage him. I was also hesitant to show my own discomfort, lest I appear cowardly, or worse, racist or elitist in his eyes. But the truth was, I was shocked by the poverty around us.

I’d known that my father’s parents weren’t well-off or educated—neither had gone to high school—but if I’d thought of them as poor, my vision of that was more rural and innocent: closely set houses with sparse furnishings in well-swept rooms, a small yard with some chickens perhaps, a tight square of a vegetable garden, some washing on the line. I’d expected to see in the windows simple white curtains, slightly frayed from constant laundering, rather than the old sheets tacked over the windows that were not already boarded up.

This was gritty ghetto poor, like the neighborhoods on the outskirts of Manhattan that, as a child, I’d peered down at from my family’s car. Again I wasn’t allowing for the fact that seventy years had passed. Bill was right about the construction of I-10 in the 1960s, bisecting the French Quarter and the Tremé neighborhood where my father was raised: the impact was devastating. Also, in 1993, the year of this visit, New Orleans was in the midst of a crack epidemic that continues today, and the area where we walked was among the hardest hit. But all I kept thinking was that no neighborhood that I had ever lived in would have declined so much.

Bill asked me for the house number as we crossed onto another block. Suddenly we were standing in front of a faded blue one-story cottage that appeared abandoned: the paint was peeling and there was no evidence of anyone living inside. We knocked for a while with no response.

“It’s small,” I said.

“It’s deep,” Bill said, peering down the alley alongside the house. “Look how far back it goes. And it looks like there used to be a nice yard.”

He suggested that we knock on the door of the neighboring house. I told the middle-aged woman who answered that my father had lived next door. “Anatole Broyard? People called him Buddy?”

She shook her head no. I went on to explain that his family moved out in the 1920s.

“Is there anyone older on the block who has lived here for a long time?” Bill asked. The woman’s son came to the door and said that we should talk to Miss Barbara down the street. “She’s lived here forever.” He offered to take us to her house.

As we followed him, I mouthed to Bill, “Miss Barbara,” slightly buoyed by the stately sound of the name.

We entered the house, and the smell of urine hit me. Towels covered these windows, and it took me a moment before I spotted in the darkness an old woman in a plaid housedress propped up on a mattress on top of a box spring in a corner. Piles of clothes surrounded her, and a small child wearing a diaper and a T-shirt lay sleeping beside her.

“This girl is trying to find out about her daddy. He lived here seventy years ago,” the neighbor explained. Miss Barbara pushed the sleeping child closer to the wall and told me to sit beside her.

“She can’t see so well,” said the neighbor, prodding me forward. I perched on the edge of the mattress and discovered that Miss Barbara was the source of the urine smell. She laid a hand on my arm and asked again who my father was. We quickly established that she had only been two when my dad’s family left town, and she didn’t remember any Broyards on the block when she was growing up. The little girl woke and started to fuss. She stood and tottered out of the room, one hand on her hip to keep her diaper from slipping down, looking, it seemed, for an adult who might change her.

After Miss Barbara talked for a while about the people she did recall from her childhood, prompted by Bill, who asked question after question in hopes of uncovering someone who might remember my father, I interrupted, saying that we’d taken up enough of her time. The diapered girl circled back into the room and started to cry. I got up, said again that we should go, thanked Miss Barbara, and headed past Bill out the door.

The walk back to the French Quarter went much faster than the way there. It was starting to get dark, and Bill suggested that we take Canal Street, which, as a well-traveled business thoroughfare, seemed safer. I was quiet while he read from the notes he’d made during the conversation. He was walking fast as he talked, making plans for the next day, trying to figure out when we could return to St. Ann Street to look for some of the people Miss Barbara mentioned. “We should go to the library first and check out the phone books, because they might have moved,” he said. “Oh shoot. I wonder if it’s open on Sunday. I forgot to look.”

I grabbed his arm. I was crying. “Just stop, all right?” He looked confused and stopped walking, but that wasn’t what I meant.

“Stop with the reporter bit,” I said, my voice rising. “This isn’t some story you’re doing. Okay? This is my family. My fucking father. Enough. All right.” I started walking again, a few steps ahead of him, crying noisily. We didn’t speak the rest of the way back.

I couldn’t explain what was upsetting me, because I was embarrassed and ashamed—that my father’s family had been poor, that I hadn’t realized how poor, that I cared so much. Bill’s ancestors had come over on the Mayflower, or close to it. His grandfather had been the dean of a prestigious medical school in New York City. Another ancestor, a great-great-great-grandmother or somebody, had been the first white woman born in Bronx County in New York. Bill had shared these details of his family scornfully, eschewing the Waspiness of his upbringing. He had told me more than once that he would gladly trade his own illustrious ancestry for my more exotic past, placing me as it did closer to the salt-of-the-earth folks who figured so heroically in the left-wing newspapers that he liked to read.

His glorification of my past I also found shameful and embarrassing, and on another level, perhaps the more honest one that made me yell at him, I recognized it as a fiction, one that was as convenient as the romantic image I’d held of my father’s youthful poverty.

When we got back to Cambridge, I made a folder, labeled it GENEALOGY, tucked all the notes we’d taken inside, and filed it away. Over the next three years, I would pull the folder out occasionally, spend half an hour trying to connect the dots, and then put it back. I didn’t return to New Orleans, nor did I try to call any of the people there who shared my last name.

In the fall of 1994 I moved to Charlottesville, Virginia, to attend graduate school. I got an apartment a mile outside of town in an old mansion that had once belonged to the owners of a woolen mill. From my front porch, I could see the mountain on which Monticello was located, home to Thomas Jefferson and his slave mistress Sally Hemings.

My first morning in my new place, I didn’t have any food, nor had I unpacked my dishes, so I headed out to a little breakfast joint I’d noticed up the road. It was a small building, not much bigger than a shack, set in between a couple of houses. I sat down at the counter, and a few moments later, a cop walked in. He went to a back hallway and returned with an apron, which he put on over his uniform before sitting down. I asked the cook, a heavy-set red-faced man with the slightly bulbous nose of a drinker, if he had a whole wheat bagel and some herb tea. He and the cop grinned.

“You’ll be wanting the biscuits and sausage gravy, ma’am,” the cop said.

“Okay,” I said, feeling my face redden slightly.

The cook added: “And there’s no tea. Just coffee.”

“That’ll be fine, then.”

I dug into my breakfast, listening to the cop and the cook chat with their y’alls and heavy drawls, and I realized that while I was only two hours from Washington, DC (and six and a half from New York), I was in the South.

The cook asked me if I was new in town.

“I just arrived,” I told him. “I’m starting school up at the university to study creative writing.”

They seemed impressed. The cook asked what I wrote.

Stories, I told him.

“True ones?” the cop wondered.

“No, mostly made-up, but I hope that they’ll feel true to people.”

“We’ll have to keep an eye out for your name,” said the cook. “What’d you say it was?”

Bliss, I told him. Bliss Broyard.

“Bliss?” he repeated, making sure he got it right. “That sure is a funny name. Sounds like one of them names the colored girls give their babies. They come up with the strangest-sounding names—Keisha, Shawanna—just make ’em up.” He and the cop laughed.

I remember that I raised my eyebrows—Is that so?—and how my face felt frozen in that expression, as if by relaxing it, I would give something away about myself.

He extended his hand. “My name’s Frank, and this here’s Fred.” He gestured to the cop’s apron: “He comes every morning.”

I shook their hands and told them that I’d be seeing them, but as I left, letting the screen door slam behind me, I doubted that I would be going back to that place again.

Charlottesville was where I began to learn about race in earnest. For the first time in my life, my world was somewhat integrated. Unlike most people’s, my sheltered existence hadn’t been challenged much in college. The University of Vermont, where I’d done my undergraduate work, was overwhelmingly white. In 1988, the year I graduated, there were only forty African American students out of more than eight thousand undergraduates. The one black student with whom I was friendly was a wealthy Nigerian guy who everyone said was a prince back in his country. While some of my course work brought me into contact with the music and literature of Africa and African Americans, my interest in “black subjects” didn’t extend to political issues. When some of the “hippie crowd” set up a shantytown in the quad to try to force the university to divest its South African holdings, my friends and I joked that demonstrators would be driven out by their own pungency from lack of showers. And my years in Boston working at the blue-blood investment firm weren’t much better. Since learning about my dad’s ancestry I’d been reading extensively about race and African American history, but I’d barely had a conversation about the subjects with anyone who knew them firsthand.

Hank, a recent graduate of the writing program, was the first African American with whom I shared my father’s secret. Over beers late into the night at a local bar, the stories came tumbling out of me: about my father being ostracized by both the white and black kids in his neighborhood, about his father having to pass to be in the carpenter’s union, and my dad’s fear of being pigeonholed as a black writer. Hank offered stories about his own light-skinned relatives. He’d also known of people who’d crossed over. Every black person did, he said. He went on to explain how racism could drive a man to deny his identity. He described how helpless and angry it made him feel when he saw a white woman cross the street to avoid him, and how difficult it was not to turn that anger inward at himself.

Up until then, I had seen my father mostly as an anomaly, a lone dropout from the struggle for civil rights, but the conversation that night made me reconsider: apparently lots of people had opted out. Much later I’d recognize how magnanimous it was of Hank to respond to my father with compassion, given that he didn’t have the same choice to control how he was perceived by the world.

With other African American graduate students, these conversations continued—about the subtle racist attitudes that persisted into the late twentieth century, but also about matters particular to being raised African American. Erica, another short-story writer, told me about the times she had to prove that she was “black enough.” She’d grown up in an inner-city Philadelphia neighborhood, and her family’s insistence that she speak “proper” English had made her a target on the street. On the other hand, she’d recently decided to lock her hair because she liked the look and was tired of the hassle and expense of chemical relaxants, and suddenly she was seen differently—more politicized and militant—especially by black men. Walton, a first-generation American whose parents were from Zaire, taught me about poetry, American jazz, and African high-life music, and explained the special meaning that the hyphenated identity of African American had for him.

I talked the most with Anjana, a cultural anthropologist who was writing her dissertation on multiracial identity. In her late thirties, Anjana was older than many of the other graduate students, having returned to school after a child and a divorce. A curvy woman with dreadlocks and a wide, open face, she was forceful, funny, and intensely fair-minded. We talked usually on the phone and often about the question of what one calls onself. Anjana had European, African, Hispanic, and Native American ancestors all in the first and second generations preceding her. For political reasons she identified as African American in any official capacity, but otherwise she resisted labels. A professor in a class she was taking once had the students go around the room and describe how they thought of themselves. People answered Hispanic, African American, Jewish, et cetera. When it came to Anjana’s turn, she wryly offered, “Empress of the Universe.”

Time and again I asked her what she would call herself if she were me, and she always gave some variation of the same response: What’s wrong with Bliss? It’s a fine name.

Some things that changed during that time: I stopped pussyfooting around race. I didn’t lower my voice anymore when I said the word “black.” I didn’t shy away from asking a question because I worried that it might make me sound ignorant or unwittingly racist. I began to stare, looking closely into the faces of my black friends, trying to see them rather than, as Ralph Ellison described, their surroundings, myself, or some figment of my imagination. I avoided that exchange of glances among white people—in a store, on the street, in a bus—when a black person has done something they disapprove of: that quick network built from strangers rolling their eyes and raising their eyebrows to remind themselves of their united front. And I started to notice the dozens of thoughts that zoomed through my brain every day carrying racially coded messages. I didn’t make a conscious decision to do this, but as I learned and talked about race, these thoughts that had once been background noise suddenly captured my attention.

I remember the first time that it happened. I was driving through the parking lot of my local supermarket and I spotted an old sedan that was speeding too fast down a neighboring row. I crossed the car’s path, and I noted with satisfaction that the driver was a black man—It figures—and in that split second, the belief that black men were reckless and inconsiderate, one that I wasn’t even aware of holding, had been confirmed, and I was pleased about it because I’d been proven right!

I parked my own car and sat there, trembling slightly. The thought lay in my brain like a mess on the carpet. I wanted nothing to do with it, but there it was, as plain as could be. Was that really me who just thought that? Or had the cook from the restaurant up the street possessed me for a moment? Given all the conversations that I’d had, all the friendships that I’d developed, what I’d learned about my father, how could I possibly be growing even more racist?

This experience repeated itself in the creative writing class I was teaching. I became conscious of slightly lowering my expectations of a black student by pandering to her hackneyed treatment of her story’s theme of discrimination. In the drugstore I watched as my annoyance with a slow cashier, who was black, widened into a general condemnation of certain types of young African American women as lazy. In the past these thoughts had passed stealthily through my brain the way the fact that you are reading subtitles during a foreign film fades from your awareness, yet their message still dictates how you see what’s happening before you. Now I began to try to intercept them.

I developed a method by which I hoped to deprogram myself. First I would forgive myself, because the only other choice, self-censure, didn’t leave any room to correct the problem. I reasoned that given the pervasiveness of racism in America, it’s impossible for a person to escape its effect. Of course I was racist, meaning I made judgments, valuations, and assumptions about people based on what I perceived their ethnicity to be. After all, fitting information into categories is how we make sense of the world. Perhaps if people felt less apprehensive about acknowledging their racist thoughts, then they could move on to addressing them.

Next I would try to identify which particular stereotype of African Americans had fueled the belief in question: that black men are dangerous, or black students aren’t as smart as white ones, or black girls have no ambition. And then, in a logical fashion, I would attempt to debunk it: What proof did I have that black men were more dangerous? Well, they are incarcerated at a higher rate than white men—but isn’t that also due in part to the bias of the justice system, issues of class, and a historical deprivation of opportunity? If all other things were equal, was there any evidence that black men would be constitutionally more prone to reckless behavior than white men? Hadn’t I in fact known white men who were reckless and black men who were not? Couldn’t that encounter in the parking lot have been a singular incident? And why should the driver be made to stand in for all other black men and not, say, all other people who drive old sedans? Couldn’t I have just as easily judged him as yet another inconsiderate old-sedan driver? Once I was satisfied that my belief was unfounded, I would make a pledge to myself to try to do better the next time.

It was strange to take such a systematic approach to changing the way I thought and behaved, as if I were making myself the subject of a psychological experiment. And it was hard work. Trying to be constantly vigilant wasn’t fun or easy. Sometimes it was difficult to resist the desire to feel superior over another person. Sometimes I got a thrill from thinking something that was ugly and extreme, the way that smelling a terrible smell can be perversely exhilarating. But mostly I didn’t feel I had much choice in challenging these thoughts. Along the way my loyalties had shifted without my even realizing it.

When I arrived at Southern Culture, the restaurant where I worked as a waitress, on the day that the O. J. Simpson trial was decided, the television in the bar was tuned to CNN and my coworkers were gathered around. Many of them were also graduate students or alumni of the University of Virginia, well educated and liberal in their politics. Everyone was white except for one dishwasher, a black man in his midfifties whom the owners had taken under their wing. He had once been in prison for failure to make payments on his child support and was constantly struggling to stay on the wagon. So long as he was sober, he’d be given work; when he wasn’t sober, he’d sometimes show up in the middle of service to ask for a drink or some money, and then the owners would turn him away.

The verdict had been announced a few hours earlier, but many people hadn’t yet seen the televised decision. The case had been the topic of discussion over beers at the end of many shifts. I stayed out of it for the most part. I’d missed seeing the live footage of the flight of the white Bronco, which was the initial hook for so many people. Also, the debates often unwittingly exposed peoples’ attitudes about race in a way that was uncomfortable to hear.

O.J. rose along with his lawyers, and we stood there too, silently, as the charges were read. Then came the verdict: not guilty. I watched the relief pass through O.J.’s body, as his mouth rose slowly into a smile. Johnnie Cochran thumped his back in congratulations. I smiled too and turned around to begin setting up for dinner. My coworkers remained staring at the television in disbelief. “It’s outrageous!” someone said, shaking his head. “He’s guilty as sin!” By the kitchen door stood the dishwasher, who wore a shit-eating, I-can’t-believe-it grin. I imagined what he was thinking: Finally, a brother catching a break, a black man buying himself some justice. He shook his head and went back into the kitchen.

I didn’t actually believe that O.J. was innocent, and I appreciated the seriousness of the crime he was accused of. I would also come to realize the complex emotions provoked by the decision for many of my African American friends. But in that lightning moment that exposed the country’s deep racial divide, there was something about O.J.’s going free that, to my surprise, made me inexplicably happy.