“A not neat knot need not need knotting.”

Climbing guide

Climbers rely on knots for tying into the rope, rigging anchors, tying into anchors, and fastening webbing and cord into loops. Dozens of knots are used, but only a few are essential to the beginner. Most importantly, when you tie any knot, do not stop in the middle for any reason; get in the habit of tying your knots from beginning to end without distraction. Otherwise, you may end up with a poor knot. If you find yourself stopping in the middle of your knot, untie it completely and start over. Practice makes perfect.

When tying a knot, the free end of the rope is either end, while the standing end refers to the middle. A bight is a loop of rope that does not cross itself. Technically, a knot either creates a loop in the rope, fastens two ends of the same cord, or creates a “stopper” in the rope end; a bend joins two free ends of rope; and a hitch grips another object, like a tree or another rope, such that if the tree or other rope disappeared, the hitch would no longer exist. Here we use the term “knot” to include knots and bends, and “hitch” to cover the hitches. Read a knot book, like The Outdoor Knots Book, by Clyde Soles, that describes in full how to tie all of the knots mentioned below (see Appendix B, Climbing Resources). We describe in photos a few of the most important knots.

Some knots, like the girth hitch and adjustable hitch, weaken the rope or webbing more than others because they bend the rope in a tighter radius. This causes shear stress (loading across the rope fibers rather than along their length) and creates extra stress in the rope or sling on the outside edge of the bend. In regular climbing scenarios, no knot will bend the rope so much as to cause breakage, but it is something to consider when massive loading is possible.

Tie your knots snug, tidily, and free of extra twists so they maintain full strength and they’re easy to check visually. As Colorado climber Michael Covington likes to say, “A good knot is a pretty knot.”

Figure eight tie-in. This is the standard knot for tying the rope to your harness, because it’s strong, secure, and easy to check visually.

A properly tied, well-dressed, and tightly cinched figure eight knot does not require a backup knot, although it’s not a bad idea, especially if the rope is stiff or new.

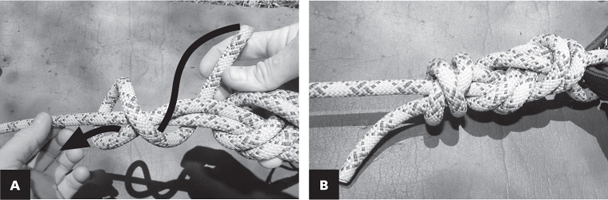

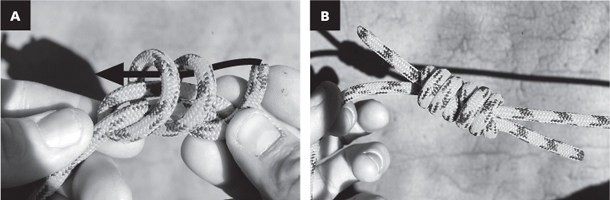

Double overhand backup. Many climbers tie a backup knot that protects the primary knot from untying. Some use a simple overhand knot, but the overhand often unties itself within a single pitch of climbing. Use an extra pass to make a double overhand if you choose to back up your figure eight knot.

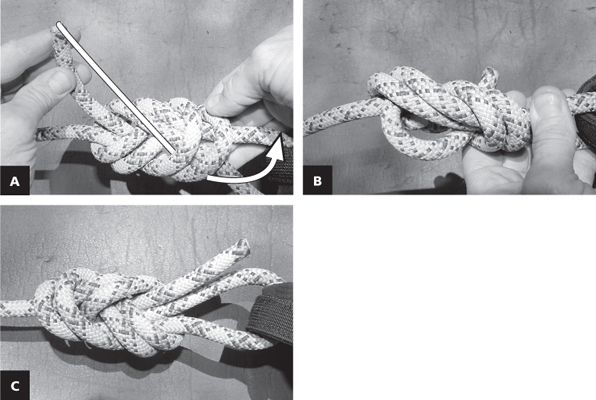

Extra pass backup. The extra pass is simply that—you pass the rope end one more time through the bottom loop of the figure eight so the knot cannot begin to untie.

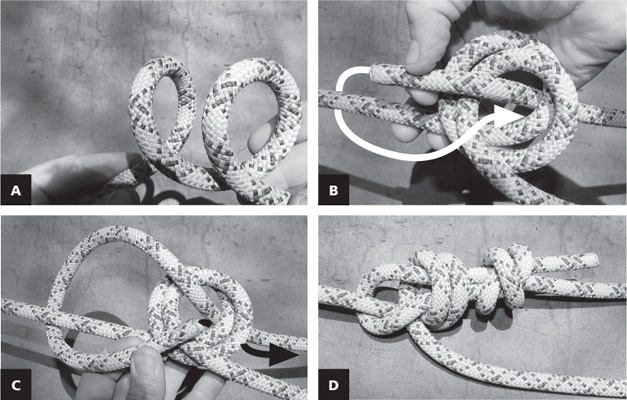

Double bowline with a double overhand backup. Many sport climbers use a single or double bowline for a tie-in knot because it’s a snap to untie after several falls. The bowline sometimes accidentally unties itself, especially if the rope is stiff. Always back up the bowline with a double overhand, and cinch both knots tight, or for the most reliable bowline, use the single bowline extra pass.

Figure eight tie-in. Make a figure eight in the rope 2 or 3 feet (shown here with a short tail for visual clarity) from the end (A and B). Pass the rope through the tie-in points on your harness (C). Be sure to use the proper tie-in points as recommended by the harness manufacturer, usually the leg loops and the waist belt, not the belay loop. Retrace the figure eight with the end of the rope (D and E). Keep the knot “well-dressed,” avoiding extra twists, and make the tie-in loop small so the knot sits close to your harness (F). Pull on all four rope strands to cinch the figure eight tight. A figure eight does not need a backup knot if it is tied correctly, but a double overhand backup (next page) is optional.

Double overhand backup (optional). Tie a double overhand knot to back up the figure eight. Coil the rope once around its standing end (A). Then cross over the first coil and make a second coil. Pass the rope end through the inside of these coils and cinch the knot tight (B). Leave a 2- or 3-inch tail in the end of the rope.

Extra pass backup. Tie the figure eight knot, then pass the rope end one more time through the figure eight to secure the knot (A and B). While not necessary, this makes the figure eight easier to untie after a fall (C).

Double bowline with a backup. Pass the rope through your harness tie-in point or around an object that you are tying off and twist two coils in the standing end of the rope (A). Bring the free end of the rope up through the coils, around the standing end of the rope, and back down through the coils (B). The free end should come into the middle of the double bowline (C). Cinch the bowline tight and finish it with a double overhand tied around the tie-in loop pulled snug against the bowline (D).

Always use a locking carabiner, or two carabiners with the gates opposed (facing opposite directions), for tying into anchors.

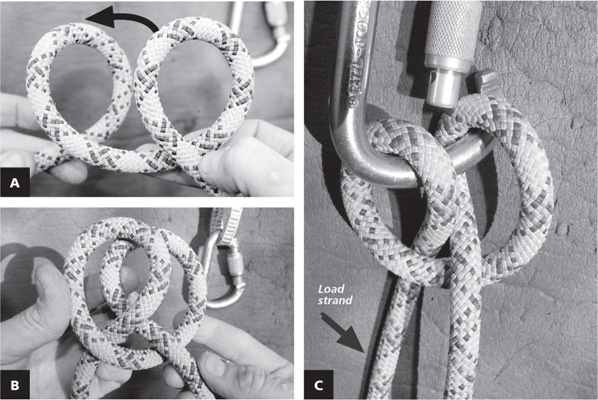

Clove hitch. The clove hitch is convenient because you can adjust the length of your tie-in to the anchors without untying or unclipping the knot. This is important because you never want to be untied from your lifeline, the rope. To extend or shorten your tie-in, simply pass the rope through the clove hitch. Once you unclip the clove hitch, it’s gone—no knot to untie.

When belaying a lead climber (see Chapter 6, Belaying), tie the clove hitch with the loaded strand next to the spine of the carabiner for maximum strength. The carabiner can lose up to 30 percent of its strength (depending on the carabiner shape and rope diameter) if the loaded strand sits near the carabiner gate. This is not a problem if the carabiner only holds body weight, but it could be dangerous if the carabiner receives heavy loading on a hard fall.

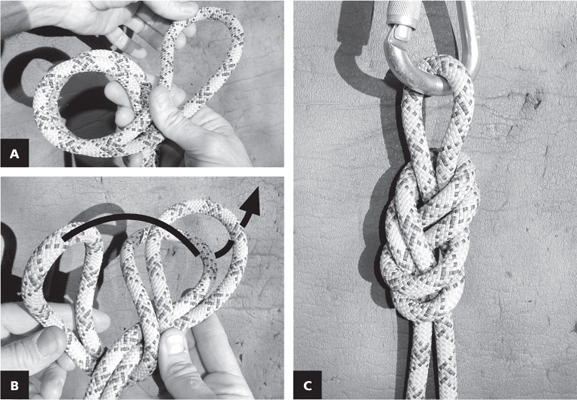

Clove hitch. Twist two coils into the rope so it looks like a two-coil spring (A). Slide the top coil below the bottom coil. Do not twist or rotate the coils (B). Clip both coils into a locking carabiner and lock the gate (C). Cinch the clove hitch tight or it may loosen and unclip itself from the carabiner.

Figure eight loop. Take a bight of rope and form a figure eight with the two strands of the bight (A and B). Dress (uncross) the strands and cinch the knot tight (C).

Overhand loop. Take a bight of rope and make a coil with both strands of the bight. Pass the bight through the coil (A). Cinch the overhand tight (B).

Figure eight loop. Tie a figure eight in the middle of the rope to make a strong loop for clipping yourself into anchors. The figure eight loop works in many other situations where you need a secure loop to clip.

Overhand loop. The overhand is useful for creating a loop using minimal rope. Because it puts a sharper bend in the rope, it’s hard to untie after being heavily loaded.

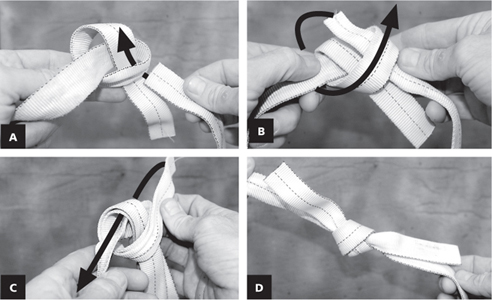

Water knot. The water knot is used for tying webbing into loops. Tie it with 2- to 3-inch tails and weight it with at least body weight before using to ensure it is tied tightly. The water knot loosens over time; check it every time you climb.

Water knot. Tie an overhand knot in one end of a sling. Match the other end of the webbing to the first end (A). Retrace the original overhand knot (B and C). Cinch the knot very tight by pulling on all four strands one at a time. The tails should be at least 3 inches long (D).

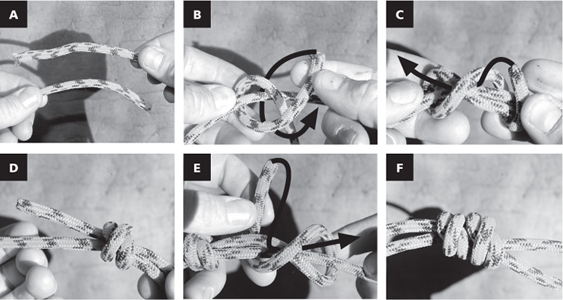

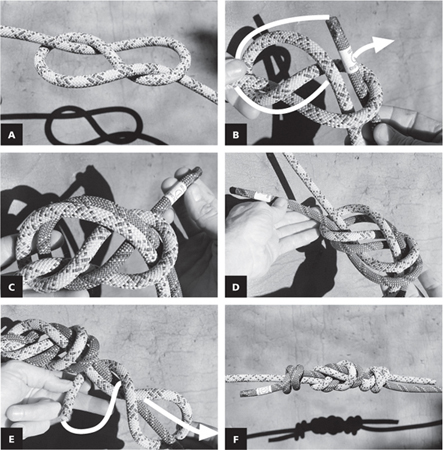

Double fishermans. With the ends pointing in opposite directions (A), coil the free end of one rope or cord twice around the second rope (or cord), crossing over the first coil to make the second one (B). Pass the end through the inside of the coils to form a double overhand (C). Repeat the first step, this time coiling the second rope around the first, but in the opposite direction (D and E), so the finished knots are parallel to each other. Cinch the knots tight (F).

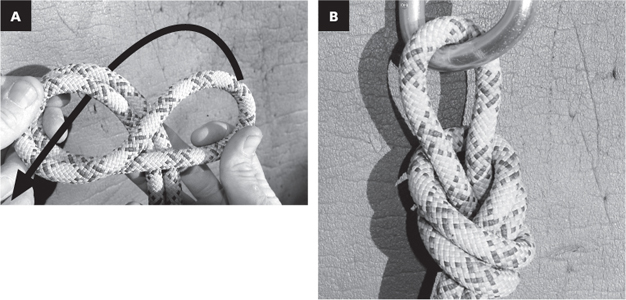

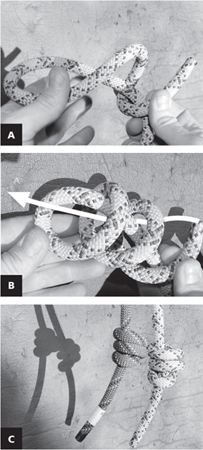

Triple fishermans. Coil the free end of one rope three times around the second rope, crossing over the first coil to make the second and third coils. Pass the end through the coils (A). Repeat the first step, this time coiling the second rope around the first, but in the opposite direction, so the finished knots are parallel to each other. Cinch the knots tight (B).

Double fishermans. The double fishermans joins cord into a loop, for example, to close a cordelette, but can be difficult to untie after being weighted heavily. Not long ago this was the most common method for joining rappel ropes and tying cordelettes, but recent tests of the flat overhand (see page 105) have shown the flat overhand’s strength to be more than adequate for climbing uses when tied tightly and neatly with a generous tail. Now, most climbers use the flat overhand in place of a double fishermans for many uses. Use a double fishermans for knots that you don’t plan to untie.

Triple fishermans. Add one more coil to the double fishermans and you get a triple. Some high-strength cords require a triple fishermans because they are so slippery; check the cord manufacturer’s recommendations.

Figure eight with fishermans backups. This is a bomber (fail-proof) knot for joining two ropes for top-roping. It can be used for joining rappel ropes, but its large profile and mass tends to snag on rock features.

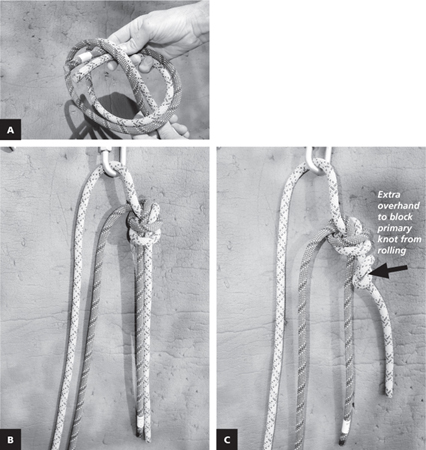

Flat overhand knot (a.k.a. offset overhand bend). The flat overhand is favored by many climbers for joining two rappel ropes or quickly tying a cordelette. It’s quick to tie, easy to untie, and best of all, it slides easily over rock edges, decreasing the chance of getting your ropes stuck. It’s more secure than it appears provided that you cinch it super tight and leave the tails at least 12 inches long. Never use a flat figure eight instead of an overhand; it is actually less secure.

To be convinced of its sliding ability, tie the flat overhand and pass it over a 90-degree edge. See how smoothly it slides? Now try any of the other rappel knots and notice how they catch on the edge.

The autoblock is a friction hitch that is the rappel backup application of the klemheist hitch (see Chapter 14, Climbing Safe). The autoblock is usually made of a cordelette (or sometimes a sling) and adds convenience and safety by backing up your brake hand when rappelling. If you accidentally let go of the rope, the autoblock “grabs” the rope and halts your descent. To stop and untangle the rope or free it from a snag, you simply lock the autoblock and use both hands to deal with the rope. The autoblock prevents overheating your brake hand on a long, steep rappel because your hand rests on the autoblock, not the sliding rappel ropes.

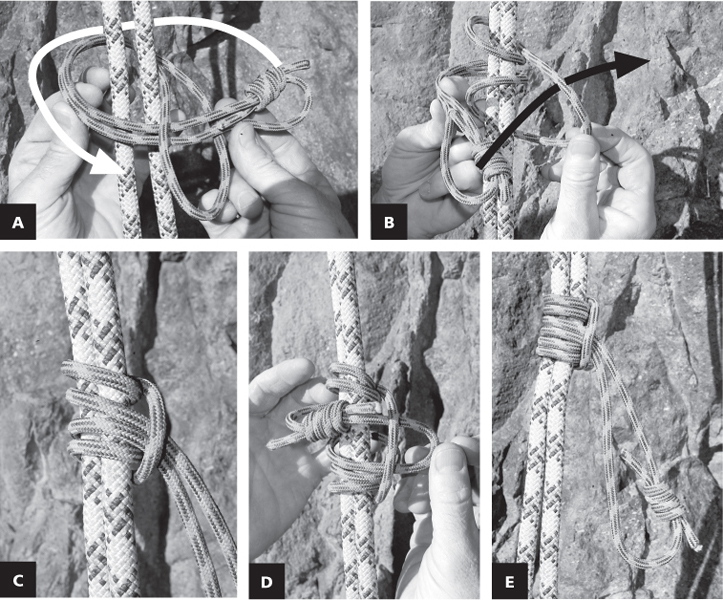

The Prusik is a well-known friction hitch for backing up a rappel and other self-rescue applications. The Prusik creates more friction than the other friction hitches. A Prusik works best with cord, but you can also use webbing. Smaller-diameter cord or thinner webbing grips better than thicker material but can be difficult to loosen if too narrow.

Figure eight with fishermans backups. Make a figure eight in one of the ropes (A). Match the rope ends and begin retracing the second rope through the eight (B and C). Finish retracing the eight (D), and tie a double overhand knot in one rope (E). Add another double overhand in the second rope to back up the figure eight (F).

Flat overhand knot. Pass one rope through the rappel anchors. Take the free end of each of the rappel ropes and tie a simple overhand with both strands, leaving tails at least 12 inches long (A and B). Cinch the overhand tight. Some climbers tie a second overhand in one or both strands, snugged up against the first one, to make this knot more secure with ropes of different diameters (C).

Autoblock. Clip a nylon sling ( -inch wide or less) or loop of cord (5 to 7 millimeters in diameter, about 14 inches long) to your leg loop with a locking carabiner. Proper length is critical (A). Wrap the sling or cord neatly (no twists) around the rope three to five times until you have a 2½- to 3-inch tail on each end (B). Clip the cord back into the carabiner and lock the carabiner (C). Wrap the cord too tight and you’ll have a slow, jerky rappel; not tight enough and the autoblock won’t grab when you need it. Practice with the autoblock to get it right.

-inch wide or less) or loop of cord (5 to 7 millimeters in diameter, about 14 inches long) to your leg loop with a locking carabiner. Proper length is critical (A). Wrap the sling or cord neatly (no twists) around the rope three to five times until you have a 2½- to 3-inch tail on each end (B). Clip the cord back into the carabiner and lock the carabiner (C). Wrap the cord too tight and you’ll have a slow, jerky rappel; not tight enough and the autoblock won’t grab when you need it. Practice with the autoblock to get it right.

Prusik. Take a thin cord (5 to 7 millimeters in diameter), wrap it once around both strands of the rappel rope and pass it through itself, making a girth hitch (A and B). Wrap the cord once again around the rope and through itself to create a two-wrap Prusik (C). If you need more friction, repeat the above procedure to create a three-wrap Prusik (D and E).

Stopper knot. Coil the end of the rappel rope three times around itself, similar to the triple fishermans knot, and pass the end of the rope out through the coils (A and B). Tighten the stopper knot. Repeat in the second rappel rope (C).

The stopper knot cannot pass through most rappel or belay devices. Tie it in the end of a rope to prevent being dropped when being lowered if the rope does not reach the ground and to prevent accidentally rappelling off the end of the rope. Both mistakes have injured or killed climbers who did not use the stopper knot. Note that the stopper knot may not prevent you from going off the rope if you rappel with a figure eight device unless you use the autoblock backup.

The girth hitch has many uses.

You can:

Fasten a sling or daisy chain to your harness for clipping into anchors (always tie into the anchors with the climbing rope if you will be belaying).

Fasten a sling or daisy chain to your harness for clipping into anchors (always tie into the anchors with the climbing rope if you will be belaying).

Fasten a sling around a tree to make an anchor.

Fasten a sling around a tree to make an anchor.

Attach two slings together to lengthen them.

Attach two slings together to lengthen them.

Connect a sling to a carabiner without opening the carabiner’s gate (perhaps because it’s your only attachment to the anchor).

Connect a sling to a carabiner without opening the carabiner’s gate (perhaps because it’s your only attachment to the anchor).

Don’t girth-hitch the cable on a nut, a chock, or any other small-diameter object, because the sling may cut under load.

You might girth-hitch two slings to your harness so you can clip them into separate anchors, or clip both into the anchor master point—the loop in the anchor rigging that you clip to attach yourself to all the anchors—for redundancy.

Girth hitch. Pass the webbing sling through your belay loop, another sling, or around any object you want to fasten it to. Pull one end of the webbing through itself (A) to create the hitch (B).

Adjustable hitch. Clip one end of a sling into the upper piece, and tie a simple slipknot in one side of the sling with the sliding side of the slipknot on the side that runs through the upper carabiner (A). Clip the loop you just created into the upper carabiner (B). If you clip the wrong side into the carabiner, the knot will slide when you pull on the sling; but clipping the right side will give you a precisely adjustable–length loop (C). Adjust the loop to approximately the desired length and clip it into the lower piece (D). Pull on your clip-in point and adjust the knot so both pieces are weighted as equally as possible in the direction of pull (E). Close-up of the adjustable hitch—it is easy to adjust and easy to untie after weighting (F).

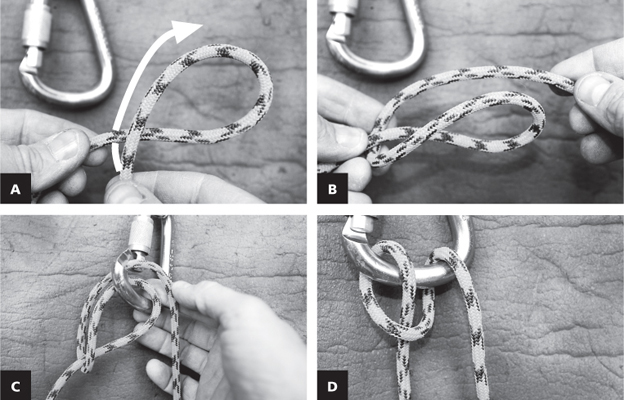

Munter hitch. Twist a coil in the rope (A). Fold one of the strands of the coil around the other strand (B). Clip the strands on both sides of the fold to create the Munter hitch (C) and then lock the carabiner (D).

The adjustable hitch is a new technique that allows a sling to be adjusted perfectly between two pieces. It can be used in place of a cordelette to create a nearly equalized single point from two pieces of gear or to clip two pieces on lead.

With a Munter hitch, you can still belay or rappel if you drop your rappel device, so it’s a great tool for your bag of tricks. The downside is that the Munter hitch twists the rope into frustrating loops.

Also called the alpine clutch, this knot can be used as an ascending device in a pinch, or for an adjustable locking hitch on the rope in rescue or hauling scenarios. The rope will slide in one direction, but lock in the other. For how to tie a garda hitch, see Chapter 14, Climbing Safe.