“Keep it tight!”

Anonymous climber

When top-roping, the climber has the security of an anchored rope overhead. It’s the safest way to climb, because a falling climber is stopped immediately. Because it’s so safe, top-roping is great for beginners, large groups, and experienced climbers who are pushing their physical limits. It’s also useful for climbing routes that offer scant opportunities for lead protection. A top-roped climber can work on a route, resting on the rope thanks to his belayer whenever he is baffled by the moves or too pumped to continue. The ultimate goal, however, is to free climb the route—climbing from the bottom to the top without weighting the rope.

Despite the relative safety of top-roping, climbers must still be attentive to each other and their surroundings and follow standard safety procedures to avoid accidents. The rigging of anchors, rope, and harnesses must be correct; the belayer must use good technique; and the equipment must be in good condition. Be careful not to fall off the cliff when setting the top anchors, and be wary of falling rock. Choose your partners wisely and check out what they’re doing whenever you climb together until you’ve learned that you can totally trust them.

Top-roped climbing normally encompasses three situations: slingshot top-roping, where the rope runs from the climber to anchors atop the route, then back down to the belayer, who’s on the ground, as shown in the opening photograph; top-belay top-roping, where the belayer is stationed at the top of the cliff; and following, where the climber follows a pitch his partner just led (removing protection along the way), so he has a rope anchored from above. This chapter covers the first two situations. (See Chapter 9, Traditional Lead Climbing for a discussion of the third situation.).

Slingshot and top-belay top-roping are only possible when you can safely reach the top of the cliff to set anchors before beginning, and when anchor possibilities exist. The cliff must also be less than a rope-length tall.

Top-roping can be hard on ropes, so it’s worth investing in a 10-millimeter or fatter rope. Static ropes can be used for top-roping, but the belayer needs to avoid letting slack build up (which she should do anyway) as the climber ascends. A medium-length fall or more on a static rope could generate dangerously high forces.

Wear a helmet while top-roping. Because the rope is running across rock far above you without being clipped into lead protection (as it would be following a lead climb), it will often move back and forth as you climb, potentially dislodging flakes and loose rocks from far above you.

Generally, you’ll top-rope on a cliff that can easily be approached from the top. Otherwise, the first climber up may lead the route to set the top-rope anchors. When rigging anchors from the top, avoid trampling fragile vegetation; it’s best if you can stay entirely on a rock surface. Use trails if they exist.

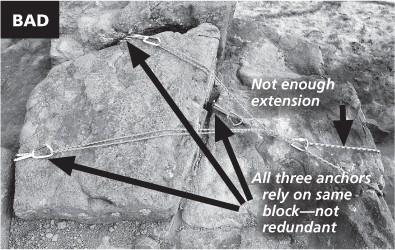

Poor: This top-rope anchor has three pieces, but they all rely on the same block, so you really don’t have redundancy. The anchor is not extended over the lip either, so the rope drag will be bad and the rope will receive extra wear. Finally, the top rope only passes through one carabiner. It’s safer to use two.

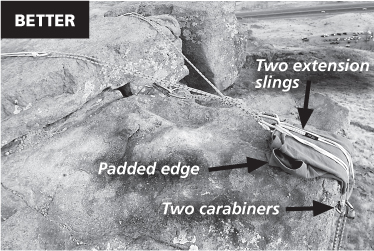

Better: Here, all the top-rope anchors don’t rely on the same block, the master point is extended with redundant slings over the lip, the edge is padded, and the top-rope runs through two carabiners. This arrangement is much better.

Forces created in falling during a top-rope climb are much lower than those possible in a leader fall, but with a little slack in the rope, they can still reach several times the body weight of the climber and belayer combined. Top-rope anchors need to be strong and secure. If they fail, it’s going to be ugly.

Scout directly above your chosen climb for possible anchors. Sometimes it’s helpful to have a spotter on the ground below the climb to help you locate the route. Setting up the anchor is the most dangerous part of top-roping. If the edge of the cliff is loose or precarious, protect yourself with an anchored rope, and take care not to knock rocks onto those below. If there are loose rocks on the edge, move them away from the edge without letting them fall off the edge, endangering anyone who may be below.

Natural anchors such as trees and large boulders sometimes provide the easiest anchors for a top-rope, because they’re fast to rig and require little gear. Usually you want three solid placements in the system, but you can make an exception if you have access to a living, green-leaved, well-rooted, large-diameter tree. Before you rig a tree, however, search for other options. Repeated top-roping on a tree, and traffic on the ground near the tree, can eventually damage it. In some areas, bolt anchors have been placed to protect the trees and plants atop the cliffs.

A completely stable, massive boulder located above the climb can also be used as the sole anchor. Just because a boulder is huge does not mean that it’s stable, however; inspect the base of the boulder to make sure the rock is stable and that it could never roll or slide. Tie two sets of slings around the tree or boulder.

There might be cracks at the top of the cliff in which to set anchors. In this case, a good rule of thumb is to set three bomber placements. Three bomber placements does not mean two marginal placements and one good one; it means three pieces that absolutely will not fail—the kind of pieces you could not pull out with a truck. If the anchors are less than perfect, set more than three—it’s your life here. (See Chapter 5, Belay Anchors and Lead Protection, to learn how to rig anchors with slings or a cordelette.)

Unless the anchor is on the edge of the cliff, extend the rigging with at least two sections of webbing or rope running over the cliff’s edge to create a clipping point for the climbing rope—with one left slightly loose. Clip the climbing rope here with two carabiners, at least one of which is a locking carabiner. A 50-foot or so piece of rope or 1-inch tubular webbing or 10-millimeter or bigger climbing rope comes in handy for rigging top-ropes.

The extension is important: If the climbing rope passes over the lip, through the anchors, and back over the lip to the belayer, you’ll have huge rope drag and the rope will abrade. If the anchors are above the top of the cliff, extend the anchor point over the lip with double sets of slings or two ropes to be redundant. Don’t trust just one sling or strand of rope to extend the anchors; repeated top-roping may eventually cut it. Unless the lip is rounded and smooth, pad the edge. An old piece of carpet is ideal, but you can also use a pack, foam pad, or article of clothing to protect the extension rope at the lip of the cliff. Tie a Prusik hitch around the extension rope and attach that to the padding to keep it in place. A piece of garden hose split in half and wrapped around the extension material also makes great padding. Even with padding and redundant extensions, it’s wise to periodically check the anchors and extension material if the top-rope is being used repeatedly.

If the edge is exceptionally sharp, or you anticipate taking large numbers of falls on the same anchor, rig your anchor equalized, and then add an extra strand of webbing or rope over the edge. Leave this one loose so repeated falling does not wear through the weighted strands simultaneously. Because you will not be able to visually inspect the anchors constantly, as you would with an anchor on a lead climb, and climbers often fall repeatedly while top-roping, the wear on the weighted part of the anchor can go unnoticed. Leaving one strand loose will ensure your safety in case the other slings fail at the same time.

The climber ties into one end of the rope with a figure eight knot while the belayer belays on the rope’s other end. The climber and belayer complete the double-check ritual before climbing. The team uses standard climbing commands to communicate. (See Chapter 6, Belaying.)

The belayer takes in rope as the climber ascends, and if the climber moves down, the belayer feeds rope out. Most importantly, if the climber falls, the belayer locks off the rope. Keep the rope tight near the ground—rope stretch on a long top-rope can allow the climber to fall several feet. Don’t climb too close to another team, because a falling climber might hit another climber or belayer.

If you need to pass a knot by yourself when belaying:

1.Take your partner’s belay device and locking carabiner, and clip it to your belay loop next to your belay device.

2.Belay her on the first rope as she climbs.

3.When the knot arrives at your belay device, ask your partner to stop climbing for a moment.

4.Tie a figure eight loop into the rope below your belay device as a stopper knot to back up your brake hand.

5.Set the second belay device on the second rope, and continue belaying the climber on the second device. Leave the stopper knot and the first device in place for the lower.

To lower your partner:

1.Lower her on the second belay device until it is a few inches above the knot joining the ropes. Ask your partner to get a stance on the rock (or pull on the belay side of the top-rope) to unweight the rope.

2.Check to be sure the first device is still rigged, then disengage the second belay device from the rope and walk back to take up the slack.

3.Lean onto the rope to make it tight, and secure the brake hand on the original rope.

4.Untie the stopper knot and continue lowering your partner to the ground. You can leave the second belay device on the rope for the next climber.

Once the climber reaches the top of the route, or an impasse, she can be lowered back to the ground. Alternatively, if lowering is undesirable, perhaps because it may damage the rope, and if there is a way the climber can hike down off the route, she should walk back to a safe spot away from the edge, call, “Off belay!” and untie. Then she can pull the rope up, look to make sure no one is below, and, if it is safe to do so, yell, “Rope!” before tossing the rope back down to the ground and walking back to the base. For a third option, the climber can climb back down the route while still on belay. This is good practice because downclimbing is a skill that can sometimes get you out of a jam and it helps to build endurance. A fourth option that is common is for her to set up for a rappel from the top, using a permanent anchor (see Chapter 11, Getting Down).

If the climb is half a rope length or less, rig the top-rope with a single rope. Always put a stopper knot in the belayer’s end of the rope so the rope can’t go through the belay device and drop the climber off the end—one of the most common accidents in climbing.

If the climb is longer than half a rope, join two ropes together for the top-rope. Join the ropes with a figure eight with a fishermans backup for maximum security. With the knot at the top of the climb next to the anchor carabiners, the climber at the base of the top-rope route can tie a figure eight loop in the rope and clip the rope into her harness belay loop with two locking carabiners, then lock them. This way, when she reaches the top of the climb, the knot will just arrive at the belayer at the bottom. A disadvantage here is that she has to climb with a length of rope trailing below her (unless the top-rope is a full rope-length high).

If you have experienced belayers, another option is for the climber to tie into the end of the rope and have two belayers pass the knot.

To belay past a knot with two belayers:

When the knot reaches the belayer, a second belayer sets another belay device past the knot (on the same rope the climber is tied into) and finishes the belay.

When the knot reaches the belayer, a second belayer sets another belay device past the knot (on the same rope the climber is tied into) and finishes the belay.

When lowering, the second belayer lowers the climber until the knot arrives at his belay device.

When lowering, the second belayer lowers the climber until the knot arrives at his belay device.

The first belayer resets his belay on the second rope, just past the knot.

The first belayer resets his belay on the second rope, just past the knot.

The second belayer disengages his belay device and the first belayer takes over. To remove the belay device, he can ask the climber to unweight the rope for a minute by holding onto the rock, or he can ask another person to hold the rope taut for a few seconds so he can free the belay device.

The second belayer disengages his belay device and the first belayer takes over. To remove the belay device, he can ask the climber to unweight the rope for a minute by holding onto the rock, or he can ask another person to hold the rope taut for a few seconds so he can free the belay device.

The first belayer steps back to tighten the rope on the climber and continues lowering him.

The first belayer steps back to tighten the rope on the climber and continues lowering him.

When belaying a top-rope from the top of the cliff, you have several options that need to be considered carefully, because once the climber is over the edge it’s hard to change plans! The simplest method is usually to lower the climber with a GriGri or assisted lock device attached directly to the anchor, which makes it easy to transition from lowering to climbing. Another choice is to use a Munter hitch directly on the anchors, which also allows an easy transition from lowering to belaying. A redirected belay works, too (see Chapter 6, Belaying). When lowering with a Munter or a tube, be sure to back up your brake hand with an autoblock or other friction hitch.

Lowering the climber wears down the rope as it drags over the edge. To preserve the rope, you may choose to have the climber rappel to the base of the climb and then belay them back up; be sure to plan the transition from rappelling to climbing and communicate it clearly.

There are three situations when directional gear placements below the anchor, even in the middle of the climb, may be necessary to keep the rope running right for the top-rope scenario and to prevent hard, swinging falls. Remember that a swinging fall sideways can be just as violent as a free fall directly toward the ground. Avoid top-ropes that set you up for a big swing, or even a small swing into an obstacle. That said, it is good to practice small swings when it is safe so that you get an idea of how quickly you accelerate in a swing and learn what is safe and what is not.

1.You may be able to climb different routes from the same anchor, by placing directional pieces to keep the rope running overhead. Climb the route directly under the anchor first, then while you’re on belay, lean over and place a directional on the neighboring climb.

2.Place directional protection on climbs that angle, limiting the swing potential. You may need to rappel or be lowered from the top before top-roping in order to place the directional protection.

3.Consider using directional placements to keep the rope from running against loose rocks or sharp edges.

EXERCISE: TOP-ROPE ANCHOR RIGGING

Go to a top-rope climbing area for this exercise. Practice setting top-rope anchors using different configurations.

Rig from a tree and boulder or two trees set back from the cliff top. Extend the anchors below the lip of the cliff with rope or webbing, and pad the edge of the cliff to protect the extension materials. Create two master point loops, clip two carabiners to the master points (at least one should be a locking carabiner), and set the climbing rope through these carabiners with both ends touching the ground. Now you can go to the bottom of the cliff to climb.

Leave the anchor rope rigged and tie into that with a figure eight knot, or set a Prusik hitch on the rope and clip the cord to your harness. This will protect you while you rig an anchor station at the edge of the cliff. Find a solid crack or two and set at least three bomber chock anchors. Rig these together with a cordelette or slings to create a master point, and then set two carabiners (at least one should be a locking carabiner) in the master point and run the climbing rope through them.