“Ah, rappelling. You’ve got to love it and hate it. It’s a great tool in the mountains, and it can even be fun, but sometimes it’s the scariest part of the day.”

Craig Luebben

Once you top out on a climb and admire the view, it’s time to get back down—safely. Depending on the situation, you may walk off, downclimb an easy route, be lowered, or rappel. The least technical descent is often the best way down, but good fixed rappel anchors can make rappelling the most convenient option, especially if no easy path exists for hiking or scrambling down. To rappel, you will likely use the same friction device you’ve been using all day to belay.

Descending sometimes comes at the end of a grueling day, in a raging thunderstorm, or in the dark, when it’s easy to be distracted or unfocused. Or you may have perfect conditions and have plenty of energy. Either way, keep your guard up. The game’s not over until you’re safely down. Descending can be hazardous.

Plan the descent before going up on a route. Many epics have been suffered because climbers neglected to research the descent. Most guidebooks include descent information. If the information is complex or unclear, ask other climbers who have made the descent. If possible, scope the descent route from the ground. Look for places to walk or scramble down, or for established rappel anchors. If you can’t find any other kind of descent, it’s often best to rappel the route you climbed.

Many cliffs have trails down their back sides; some even have roads. If so, walking down is probably the safest and often the quickest way back to the base. Bring the descent information so you know which way to go. While some climbers enjoy rappelling, others despise it and will take a long hike down to avoid it.

Many descents require some downclimbing. If the downclimbing is easy and on solid terrain, the team might climb or scramble down unroped. Be careful, though; falling off easy terrain while unroped on the way up or down is one of the most common climbing accidents at all experience levels. And if the exposure is steep anywhere below you, your tumble could be fatal.

Pull the rope out and rappel or belay for even the shortest tricky section. Most of the time, you should downclimb facing the rock. Never climb unroped down anything you don’t feel absolutely confident about. Likewise, never coerce your partners to down-solo anything. Instead, be the first to offer a rope. When downclimbing, keep close together so all climbers have ready assistance.

As a rule, the more experienced partner should climb down first to find the logical route. You may be able to offer an occasional spot to safeguard your partner climbing down behind you. Another option is to lower your partner, or have him rappel, then downclimb to him.

If the downclimbing section is difficult or long, it’s usually best to rappel, provided you can find good rappel anchors. If rappel anchors are unavailable, the team can belay each other down. The weaker climber goes first and sets gear to protect the last climber. The last climber should climb with extreme care, because she is downclimbing above protection that she didn’t place. It’s rare that a team downclimbs anything very technical, because rappelling is safer and usually faster.

Being lowered is the most common way to descend a short sport route, but it only works if you’re less than half a rope length above the ground. It’s also possible to lower your partner from above, up to a full rope length, but then you need to rappel to reach him.

When you lower a climber, the rope’s other end should be tied into you or fixed with a stopper knot so the rope end could never come free from the lowering device. (When using a figure eight belay device or Munter hitch, the stopper knot does not provide a reliable backup; anchor the rope end instead.) It is safest to always back up the lower as shown in Chapter 6, Belaying.

So you’ve climbed a multipitch route and it’s time to get down. Lacking an easy walk-off or scramble, you can make multiple rappels to descend. Rappelling is a technique that allows you to do a controlled descent down a rope. Most developed cliffs that lack a walk-off have one or more established rappel routes with anchors fixed in convenient places. The rappel route may descend your climb, another route, or even a route designed for rappelling only. This section outlines the rappel descent step by step. Rappelling can be an exhilarating part of the climbing process. But because all of your hopes for safety rely on your anchor point, you better be extra sure of its reliability and triple-check your and your climbing partner’s tie-ins before heading over the edge.

Anchors are fixed in place on established rappel routes. They come in many forms, some good and some horrendously dangerous. It’s up to you and your partners to inspect all fixed anchors and rigging, and back them up with your own gear or extra slings if they need it. Don’t get into a sloppy habit of simply trusting whatever fixed gear exists.

Rappel anchors are not subjected to huge forces like belay anchors can be, but they hold your full body weight plus some extra for “bounce” every time you rappel. Solid, redundant anchors are essential for rappelling: If your rappel anchors fail, you will most likely die. Occasionally, rappel anchors consist of a single tree or rock feature, but generally you want at least two bomber anchors, rigged so they share the load. See Chapter 5, Belay Anchors and Lead Protection, for details on rock anchors.

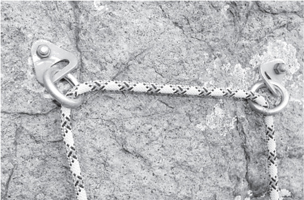

Bolt rappel anchors. This rigging, with the rappel rings spread horizontally, can put some nasty kinks in the rope. It’s better if the rings are extended by chain so they can come together, or if one bolt is set above the other and extended with chain.

Some of the safest and most convenient rappel anchors are bolts. A bolted rappel anchor should have at least two ⅜-inch or bigger-diameter bolts that are well placed in solid rock. The cleanest setup has steel rings, oval links, or chain links attached directly to the bolt hangers, with the rappel rings from all the bolts hanging at about the same level.

Rappel anchors blend well with the rock when painted or coated in camouflage colors. Such a bolted anchor is less unsightly than a stack of tattered webbing flapping in the wind, and it’s longer lasting, because steel does not degrade quickly like webbing does.

Bolts slung with webbing are ugly, and the webbing must be replaced periodically due to ultraviolet radiation damage. If you must sling the bolts with webbing, choose a color that blends with the rock. Avoid leaving bright webbing on the rock. Because rappel anchors stay in place indefinitely, make them discreet.

Large, living, well-rooted trees with green leaves make good rappel anchors. Webbing slings should be tied around the tree and fixed with rings for the rope to run through. You can rappel by running the rope directly around a tree, but the friction may make it difficult to pull your ropes down, and worse, when rope is pulled it will strip some bark from the tree and could eventually girdle the tree and kill it if it is done frequently. In areas with high traffic, it’s better to establish a bolted anchor to protect the tree and surrounding vegetation.

Natural rock features make good rappel anchors, provided that the feature is solid and securely holds the sling in place. Natural features are appealing because you only need to leave some webbing and a ring to build an anchor.

Fixed pitons can make great anchors or lousy ones. The problem is that you can’t always tell whether they’re good by looking at them. Many fixed pins have been in place for decades and are dangerously corroded. Others are damaged from being overdriven. Thermal expansion and contraction of the rock can eventually work pitons loose. Inspect fixed pitons well and back them up if possible.

Fixed nuts or cams set in solid rock can make good rappel anchors. Make sure the placements are good and the webbing is in decent shape.

Rappel rings provide a point for attaching rappel ropes to the anchors. The best ones are made of steel and are at least ¼ inch in diameter (⅜ inch is better). Steel rings are durable and should endure thousands of rappels. Because steel and nylon create little friction against each other, the rope can be pulled easily from below. Ideally, the rappel ropes run through two or more rings for redundancy.

At least one company makes aluminum rappel rings. While these are light, they are not durable. They can be eroded after only a few dozen rappels, especially in sandy areas where the rope becomes abrasive. Inspect aluminum rings closely or, better, replace them with steel rings. Some climbers carry one or two “rapid links,” steel links that can be opened and placed around webbing for replacing bad or nonexistent rappel rings.

Carabiners can also be used as rappel rings. It’s best to use at least one locking carabiner or tape the gates of the carabiners shut so they cannot accidentally open. Two carabiners with the gates opposed make a secure, strong rappel ring. If you find carabiners at a rappel station, don’t take them, and remind your partner that they are fixed.

Ideally, the rappel rings attach directly to the bolt hangers via steel or chain links. If they’re attached with webbing, closely inspect the webbing before trusting it. If it’s faded or stiff, it may be severely weakened by ultraviolet radiation. Inspect the entire circumference of the webbing slings. Rodents sometimes chew webbing, especially in hidden spots behind flakes or trees. Coarse rock can abrade the slings, especially in high-wind areas. If the rigging includes no rappel ring, check the webbing for rope burns from previous rappel ropes being pulled through it, and perhaps add another sling, and possibly a rappel ring or two.

Frequently you’ll encounter rappel anchors clogged with a cluster of tattered webbing (shortened to “tat”). Sometimes it’s best to cut the whole mess away and rebuild it from scratch—provided you have the experience and patience to rig it right. Run a loop of webbing from each anchor to the rappel ring and adjust the loops so all the anchors share the weight. It’s helpful to carry 7-millimeter cord (a cordelette and a knife are ideal) for rebuilding anchors. All climbers share responsibility for maintaining fixed anchors.

Keep the V-angle below 60 degrees if possible, and 90 degrees at the maximum (see Chapter 5, Belay Anchors and Lead Protection, for more on V-angles). Avoid the American triangle, where a single sling passes through all the anchors in a loop. The American triangle multiplies the force on the anchors, which is particularly dangerous if the fixed rappel anchors are not bomber and you are unable to back them up. Each anchor should have its own sling.

If the anchors sit at the back of a ledge, extend the rappel point over the lip so the rope runs cleanly. If the rope bends abruptly across the lip of the ledge it can be hard to pull from below, especially if the knot jams at the edge. Use at least two separate lengths of cord or webbing to make the extension redundant. If you don’t, the last climber down should move the knot over the edge before rappelling so the rope can be retrieved after the rappel. Consider having the first climber down test the pull or drag on the rope before the last person rappels.

If the anchors are suspect, add a piece of protection or two to the cluster and adjust the rigging so it’s clean and equalized. Perhaps you can find natural protection where you only need to leave a sling, or maybe a crack where you can fix a hex or wired nut. Don’t be cheap when backing up anchors. Being miserly with a $10 nut, or even a $60 cam, is senseless given the huge penalty for anchor failure. Eventually you will have to leave behind some of your own gear at an anchor. Using girth hitches in place of carabiners can minimize the amount of gear you must leave behind, but this is not the time to be cheap on the overall strength of the anchor.

Sometimes, even when the anchors are solid enough for rappelling, it’s comforting to have temporary backup anchors until the last person rappels. The backup anchor will be retrieved by the last person, so set as many anchors as you need. Two good placements, equalized, should suffice. Clip the backup anchors to the rappel ropes with a locking carabiner (or two carabiners with the gates opposed) just below or between the rappel rings. Make sure the load is on the primary anchors, not the backups, so the first climber down tests the fixed anchors for the last person, who will rappel without backups.

The first climbers to rappel should carry the bulk of the gear, and, in theory, the lightest climber should go last. That way the primary anchor gets heavily tested with a backup anchor in place, and then the last climber down removes the backup anchor and rappels. If the primary anchor is poor, leave the backup anchor in place.

Rappel anchors are usually located in exposed places. The entire climbing team should clip into the anchors while rigging rappels. There are a variety of ways to clip to the anchors, and the safest is to use two redundant attachments—even using two chains of regular quickdraws is safer than a single daisy chain and a locking carabiner.

Rappel backup placed so the primary anchor takes the load. First climber down rappels with the backup in place.

Last climber down removes the backup anchor and rappels smoothly.

If the rappel anchors are modern double bolts, there is no need to equalize each anchor—the most force the bolts will hold is little more than the body weight of the climbers, and much time will be wasted rigging. Instead, each climber can girth-hitch two shoulder-length slings to her harness belay loop, then clip a sling to each bolt. Preferably, at least one of the carabiners is locking. This method can get clustered if you have more than two climbers, although it is manageable with three experienced climbers. Think ahead, and add a carabiner to each bolt, clipping into the added carabiners so nobody gets pinned underneath another’s clip-in point (an example of an occasion when attaching carabiner to carabiner is an excellent and safe technique).

If a single shoulder sling is too short to reach the master point, use a double-length sling, or girth-hitch two standard slings together. Some climbers use a daisy chain, which has multiple loops for clipping rappel and belay anchors. Where you clip depends on the hardware at the station. With chain links, you can clip into any of the links or the bolt hangers. One climber can also clip into the clipping carabiners of another climber, provided that he rappels before that climber on the next rappel.

Another option is to rig the anchors at each station with a double sling or cordelette to create a master point. Each climber girth-hitches two shoulder-length slings to his harness belay loop and clips them to the anchor master point with a locking carabiner. This method works well when more than two climbers will be rappelling.

To rappel with a single rope, pass the rope through the ring of a fixed rappel anchor and set the rope’s midpoint at the ring. Many ropes have a middle mark; bicolor ropes change patterns in the middle. If the midpoint is not marked, take both ends of the rope and pull the two strands equally through your hands to find the rope’s midpoint.

Tie a stopper knot in the end of each rope to prevent the chance of accidentally rappelling off the ends of your ropes, a mistake which is usually fatal. This is especially important when rappelling in a storm, if it’s dark, if you’re not very experienced, or if you’re heading down an unknown rappel route.

Some climbers tie the ends of their ropes together for a backup. However, this prevents the ropes from untwisting and can cause spectacular rope kinks at the end of the rappel. Therefore, it works better to tie a separate stopper knot in each rope.

Now, after the entire team rappels, you can retrieve the rope from below by first untying the stopper knots and then pulling down one rope strand. When rappelling with one rope, you can only rappel half a rope length and still retrieve your rope from below.

To make a full rope-length rappel, you need two ropes. Pass one of the ropes through the rappel ring or rings and tie the two ropes together, with the knot joining the ropes set near the rappel anchor. After rappelling, pull down the rope that does not pass through the anchors to retrieve the ropes. Before retrieving the ropes, pull outward gently on them, one in each hand, eyeballing their alignment to the top to make sure that the lines aren’t twisted. If you pull the wrong rope, the knot will jam in the anchor rings. If this occurs, try pulling the other rope.

With 200-foot ropes you can sometimes skip rappel stations and make two rappels into one. This can speed your descent, or it can cause a real mess if you get your ropes stuck 200 feet above. Skip stations to make long rappels only if the rock is smooth and lacks rope-sticking features such as trees, bushes, cracks, flakes, blocks, and knobs. Also, be certain that the ropes reach the next set of anchors or the ground. Check the stopper knots if you get anywhere near the ends of the ropes.

There are several knots recommended for joining two rappel ropes together. The standard rappel knot worldwide, even when using two ropes of different diameters, is now the flat overhand (see Chapter 4, Knots) because it is extremely fast to tie and slides easily over edges, decreasing the chances of getting a rope stuck because the knot got jammed on an edge. When tying a flat overhand, make the tails 12 inches long, clear

ADVANCED TIP

Some climbers rappel with a single rope joined to a thin tag line, sometimes as thin as 7 millimeters in diameter, to save weight on the climb. This system works best if the thicker rope passes through the anchors. Otherwise, the thin rope may slip faster through the rappel device and stretch more than the thicker one, causing it to creep through the anchors. This could be especially dangerous if the rope runs through webbing instead of a rappel ring.

There are some downsides to this method. If the rappel rope gets stuck above, you may have only a 7-millimeter line for protection while you climb up to fix the snag (see Chapter 14, Climbing Safe). Narrow rope is also hard to grip if it’s a tough pull so some climbers prefer an 8-millimeter tag line. Either way, you always have to set the fatter rope in the rappel rings, so you lose the efficiency of alternating which rope runs through the rings on multipitch rappels. any twists out of the knot, and cinch the knot tight before weighting it.

The stopper knot increases the possibility of getting the rope stuck below you, particularly if it’s windy and the rope is blowing sideways, or if the rock is super featured. If you’re highly experienced at rappelling, you might forgo the stopper knot in these situations, but be sure to use a friction hitch backup and be hyper-aware of the rope ends as you rappel.

In high winds you can lower the first climber down, who then ties the ropes off to the lower anchors so they can’t blow too far sideways, then you can rappel. This may not be good if you can’t see her on the way down as you lower her, though. You can also rappel with both ropes wrapped in tight sling coils, one on each hip, or flaked into a pack, then feed rope out as you rappel.

When the ropes are threaded through the anchor, many climbers are tempted to toss the ropes down the face without care. But then the ropes get tangled on every bush, ledge, and flake on the face. To get the ropes down so you can rappel without stopping to clear them, first lower the top section of the rope (the part closest to the anchors) down the face. Lower it until the rope hangs up on a ledge, bush, or other obstacle, or until about one-third of the rope is out.

Next make butterfly coils with the middle section of the rope; yell, “Rope!”; and toss the coils down while holding the final 20 or 30 feet of rope in your hand. Finally, toss this last section of the rope outward from the face to clear any obstacles (but don’t toss it outward if it’s going to catch in a tree!). If it’s a bit windy, pitch the rope hard and straight down, like a baseball. This technique often gets the ropes all the way down on the first try. You can also coil and toss both strands of the rope(s) simultaneously if the situation allows.

Be careful when dropping your ropes. It’s rude to toss a rope down on climbers below you, and it’s dangerous if someone is leading below. If climbers are below, either wait for them to finish their climb or slowly lower the ends of the ropes down. This may cause the rope to hang up, but it will be safer for the other climbers and you can free the snags as you rappel.

Once the ropes are set, rig the rappel device, which creates friction on the rope to control your descent. Be sure to double-check that your device is properly attached to you and to the rope before you unclip from the anchors—it is easy for an incorrectly threaded rappel device to hide under clothing or other gear.

Some belay devices work better for thinner ropes, barely accepting the girth of a fatter rope, while others accept fatter ropes but provide insufficient friction on skinny ropes for heavier climbers.

To rig a rappel tube:

1.Keep the belay device cable clipped in to its locking carabiner, which should be attached to your harness belay loop, so you can’t drop it. Take a bight from each rope strand and pass it through its own slot in the rappel device (A).

2.Orient the device so the ropes going up to the anchor are on top and the ropes going down to your brake hand are on the bottom (B).

3.Clip both bights of rope into the locking carabiner attached to your harness belay loop, and lock the carabiner (C).

4.Add an autoblock backup attached to the harness leg loop below the device (D).

Follow the manufacturer’s instructions for rigging and rappelling with any device.

Figure eight devices work well for rappelling and they’re easy to rig, but because they do not work well for belaying, and modern tube devices work well for both belay and rappel, most climbers these days forgo figure eight devices. Figure eight devices can also twist the rope and cause rope kinking, and they’re heavier and bulkier than other rappel devices.

Because figure eight devices can allow twists in the ropes to pass through, ropes are also often harder to pull down. When rappelling with a figure eight, consider girth-hitching a sling to your belay loop and clipping that sling to one of the rappel ropes with a carabiner. The carabiner prevents twists from passing up the rope so you can easily separate the ropes before you pull them down. However, it is best to leave the figure eight to the sport rappellers and carry a tube device instead.

On steep rappels, especially with thin ropes, it’s possible to feel as if you’re not getting enough friction from your rappel device. It can be frightening to think that you’ll lose control of the rappel, and you might burn your hands. Using a rappel backup (described next) usually solves this problem. You can also gain friction by:

Using two or three carabiners to clip the rappel ropes below your device.

Using two or three carabiners to clip the rappel ropes below your device.

Running the brake rope around your hip.

Running the brake rope around your hip.

A rappel backup makes rappelling safer and easier to control. The backup is simply a friction hitch wrapped around the rappel ropes and clipped to your harness. It slides down the ropes if you hold it loosely in your hand, and locks onto the ropes if you let go. With any rappel backup, consider it a backup and not a bombproof system on its own. So don’t just let go with both hands suddenly, assuming the hitch will hold 100 percent of the time. Instead, ease onto it with your brake hand on the rope to ensure it is working properly, and remember that the hitch will behave differently at different points on the same rappel. Practice ascending a rope with the autoblock and other friction hitches to learn their limitations and capabilities.

Backing up the rappel with an autoblock takes a few extra seconds, but it may save your life. The autoblock rappel backup makes rappelling safer and easier to control; adds friction to your rappel so you don’t burn your hands; allows you to easily stop and use two hands to free the rope if it’s twisted and tangled; and locks automatically to halt your rappel if you lose control of the rope due to inattention or rockfall. (See Chapter 4, Knots, to create a rappel backup using an autoblock.)

Because the autoblock is positioned below your belay device (where the brake hand grips), it holds much less than full body weight. That makes it easy to loosen, so you can resume rappelling after locking the autoblock. Any friction hitch can back up a rappel, but the autoblock is quickest to rig, especially when making multiple rappels, because the cord stays clipped to your leg loop while tying and untying the autoblock. However, the loop length is critical, so test your rig in advance. A Prusik hitch also works, but an autoblock slides easier down the rope and so is better for rappel backup.

Do not allow the autoblock to touch the rappel device. If the cordelette or sling used for the autoblock is too long and it lightly touches the device, it will not be able to grab the rope and lock properly. If the autoblock goes inside the device, it can jam. This predicament can be difficult to escape without good knowledge of self-rescue techniques (see Chapter 14, Climbing Safe). Ideally, the belay loop creates enough extension so the rappel device rides above the autoblock.

If your harness lacks a belay loop, girth-hitch a doubled sling onto your harness tie-in points and clip the rappel device to the sling. This extension will prevent the autoblock from touching the rappel device. This solution also works if your belay loop is too short to keep the rappel device and the autoblock separated. In this situation, you can rig the autoblock on your belay loop rather than a leg loop. Beware of getting the extended rappel device caught in your hair or above the lip of an overhang with your body below; getting unstuck can be difficult.

The shoulder sling forms the optimal length autoblock for most harnesses, provided you first girth-hitch the sling (which can be left in place for multiple rappels) around the leg loop, wrap the autoblock four to five times, and clip it into a carabiner also attached to the leg loop.

If you have a slippery new rope and a slippery new sling, the autoblock may not lock onto the rope when you need it to. In this case, cord or a sling that has softened with use will work better than new webbing. If the same sling is used for a large number of autoblock backups, it will eventually show wear due to friction, and may need to be retired, but webbing should be retired regularly anyway. Many climbers carry a 5-foot length of cord for rescue applications and then use it tied into a shoulder-length loop for autoblock rappel backup rather than slings.

After you have rappelled, hold the rappel ropes to back up your partners while they rappel. If they start to slide out of control, pull the ropes tight to stop them. This is called the fireman’s belay. The “belayer” needs to pay close attention, watching the rappellers every second, because an out-of-control rappeller can smack a ledge or the ground in seconds.

It’s difficult to know when to tighten the ropes if you can’t see the climber rappelling. If the anchors are great and you have a partner who lacks rappel experience, you can stop at a ledge midway down and “belay” him down to you, then finish the rappel and again “belay” him down. This allows you to see your partner the whole way down. An autoblock rappel backup is crucial to make this tactic safe.

Fireman’s belay

If you rappel second or third, rig the autoblock while your partner rappels. When it’s time to rig your rappel device, pull some rope up through the autoblock. The autoblock will hold the weight of the rope so you can easily feed the rope into your rappel device. If you don’t do this, you will have to fight the weight of the ropes while rigging the device.

The autoblock must have a proper number of wraps around the rappel ropes. Too few wraps and the autoblock will not lock, plus it may extend far enough to jam in the rappel device. Too many wraps and the rope will barely feed through, causing a torturously slow and strenuous rappel. Practice thoroughly with the autoblock before relying on it. You’ll notice that at the beginning of a long rappel, the weight of the ropes can be enough to act as an autoblock even without an additional friction hitch on the rope; as you get lower and there is less rope weight hanging below you, however, the device slides easily and a friction hitch becomes necessary to back up a rappel. If you find the hitch that seemed to work great at the top is no longer providing enough friction to stop, consider wrapping the rope around your leg four to five times to hold you while you add an extra wrap to the autoblock.

Many climbers forgo the autoblock backup while rappelling. This is because rappelling without a backup is very easy and faster, and getting the autoblock system dialed takes practice. Rather than falling into the habit of rappelling without a backup, practice until using the autoblock backup becomes second nature.

To rappel: Hold the friction knot loosely in your hand as you rappel. This allows the rope to slide through.

To stop: Relax your grip on the friction hitch and it will cinch onto the ropes and halt your rappel. Keep your brake hand engaged until you’re sure the autoblock is locked. Wrap the rope four to five times around your leg as a backup—this works even without an autoblock in the system.

An old fashioned technique for backing up the rappel is to rig a Prusik hitch above the belay device and clip it to your harness. When rappelling, hold the Prusik and slide it down the rope. The Prusik should extend from the harness no farther than you can reach, or it could lock up and strand you on a steep rappel. Even within reach, a Prusik loaded with full body

weight can be hard to loosen to resume rappelling. Most guides and climbers have abandoned this system in favor of the autoblock method, which is more convenient and works better.

If you have to pass knots in the rope while rappelling, setting the friction hitch above the belay device can be advantageous (see Chapter 14, Climbing Safe).

Every detail must be correct when you rappel. It’s critical to double-check the entire “safety chain” before unclipping from the anchors. Many accidents, often fatal, happen on rappel.

Double-check:

Your harness buckle and your partner’s harness buckle

Your harness buckle and your partner’s harness buckle

The rappel device and locking carabiner, making sure the carabiner is locked onto the belay loop with both rope strands and the device cable clipped inside

The rappel device and locking carabiner, making sure the carabiner is locked onto the belay loop with both rope strands and the device cable clipped inside

The anchor and the rope’s attachment to it

The anchor and the rope’s attachment to it

The knot joining the ropes

The knot joining the ropes

The autoblock backup

The autoblock backup

The slings girth-hitched to your harness for clipping into the next anchors

The slings girth-hitched to your harness for clipping into the next anchors

So you’ve rigged the ropes and the rappel device onto the ropes, whipped on an autoblock, and double-checked the whole system. It’s time to rappel.

1.Pull all the rope slack down through the rappel device so the device is tight onto the anchors.

2.Set your brake hand on the rope below the rappel device.

3.Put your guide hand above the rappel device.

4.Keep your feet shoulder-width or more apart and knees slightly bent.

5.Lean back onto the rope (unless the anchors will be compromised by an outward pull).

6.Let rope slide through the device without moving your feet until your legs are almost perpendicular to the wall. Bend at the waist to keep your torso upright.

7.Switch your guide hand onto the autoblock, and move your brake hand to the ropes below it.

8.Walk down the face, allowing rope to feed smoothly through the rappel device. Keep the rope between your legs. Don’t bounce, jump, or fly down the rope. Just walk.

If you rappel in a jerky fashion, with rapid accelerations and decelerations, you drastically increase the force on the anchors and can damage the rope if it passes over rough edges. Big bounds, rapid descents, and swinging sideways can have the same effect. Rappel at a slow, steady speed to avoid jacking up the force on the anchors.

To rappel past a roof, plant your feet on the lip and lower your body down. Cut your feet loose once your body is below the lip to avoid smacking your head.

Sometimes the rappel anchors are set below the ledge you are standing on so the ropes can be pulled cleanly after you rappel, or are otherwise in a difficult location to reach. If a fall is possible while downclimbing to the anchor, place an anchor using your gear above the rappel anchors and belay one climber at a time down to the anchors, with the last climber down cleaning the upper anchor. In this case the stronger climber should descend last.

Caution: The girth hitch has been known to fail due to the webbing being cut under shock-loading when tied around webbing of a different diameter—like a harness belay/rappel loop. This dangerous scenario can happen if you reach down to clip an anchor below you and then fall onto it, creating a short, hard fall. For this reason, always use two slings when using the girth hitch to your belay loop.

ADVANCED TIP

If you have two ropes tied together, the flat overhand rappel knot may slide over the edge, but the other types of rappel knots can jam on the lip of the ledge when you try to pull the rope down. To prevent this, the last climber down can slide the rope through the rappel rings to move the knot to just below the lip. Now rig the rappel device and autoblock below the knot and clip into the rope below the autoblock with an overhand on a bight tied into both ropes—don’t trust the autoblock to hold a shock-load. Climb hand over hand down the rappel ropes to get below the ledge where the rappel device can hold your weight, untie the overhand backup, then rappel down. Don’t do this if you need every inch of rope to reach the next rappel anchors.

During the rappels, the first and last climbers in the team assume certain duties. If you have only one rappel to the ground, it doesn’t matter who descends first, because the ground is easy to find. On multipitch rappels, the most experienced climber often descends first, to make routefinding and anchor decisions.

The first climber to rappel performs the following duties:

Rig the rope to rappel, complete the double-check ritual, verify that both rope ends have stopper knots, and begin rappelling.

Rig the rope to rappel, complete the double-check ritual, verify that both rope ends have stopper knots, and begin rappelling.

Find the descent route and the next set of anchors. Carry the rappel topo or description if you have one.

Find the descent route and the next set of anchors. Carry the rappel topo or description if you have one.

Watch out for loose rocks and sharp edges. Look for places where the rope or the knot could jam, and warn your partners about it so they don’t get the rope stuck.

Watch out for loose rocks and sharp edges. Look for places where the rope or the knot could jam, and warn your partners about it so they don’t get the rope stuck.

Clear rope snags as you get to them. Don’t rappel below rope snags, because you may not be able to free the rope from below, and you may pull a rock onto yourself trying. You can use both hands to free the ropes if you lock the autoblock and leg wrap.

Clear rope snags as you get to them. Don’t rappel below rope snags, because you may not be able to free the rope from below, and you may pull a rock onto yourself trying. You can use both hands to free the ropes if you lock the autoblock and leg wrap.

Inspect the next anchors and rigging, back them up if necessary, and clip into them.

Inspect the next anchors and rigging, back them up if necessary, and clip into them.

If no rappel route is established, build rappel anchors at each station.

If no rappel route is established, build rappel anchors at each station.

Consider a “test pull” on the rappel ropes for a foot or two in order to ensure that they slide and can be retrieved after your partners rappel.

Consider a “test pull” on the rappel ropes for a foot or two in order to ensure that they slide and can be retrieved after your partners rappel.

Leaving several feet of slack in the rappel line, tie the ropes into the anchor using a single large overhand on a bight. This makes it safer and easier for the second person down to reach the anchor easily, especially if the rappel angles to the side even slightly.

Leaving several feet of slack in the rappel line, tie the ropes into the anchor using a single large overhand on a bight. This makes it safer and easier for the second person down to reach the anchor easily, especially if the rappel angles to the side even slightly.

Untie the stopper knot, feed the pulling end of the rope through the rappel rings on the next anchors, and retie the stopper knot for when your partners come down.

Untie the stopper knot, feed the pulling end of the rope through the rappel rings on the next anchors, and retie the stopper knot for when your partners come down.

Possibly provide a fireman’s belay to your partners as they rappel. This shouldn’t be necessary if they are using autoblock backups.

Possibly provide a fireman’s belay to your partners as they rappel. This shouldn’t be necessary if they are using autoblock backups.

The last person to rappel ensures that the rope runs true and untwisted and stays out of cracks and away from other obstacles where the rope could jam when pulled during removal.

Once you arrive at the next anchor station and clip in, stay attached to the rappel rope until you have inspected the anchors, anchor rigging, rappel ring, and your attachment to the anchor. Check that the slings are properly attached to your harness and clipped to an anchor master point with a locked carabiner. Once you’re solidly attached to good anchors, dismantle the rappel device.

1.Unlock the carabiner, and unclip the cable and the rope strands from it.

2.Reclip the rappel device’s cable so you can’t drop the device.

3.Remove the rope from the rappel device.

Rappelling communication is pretty simple. After you’ve rappelled and dismantled your rappel device and autoblock, you call up, “Off rappel!” so your partner knows that he can start rigging to come down.

When you pull the ropes down, yell, “Rope!” to warn any nearby climbers.

Once the team is established at the new anchors, it’s time to retrieve the ropes. Ideally, the first climber down has already fed the rope to be pulled into the new rappel rings and retied the stopper knot in the rope end. Then:

Make sure the stopper knot is untied in the other rope or it will jam in the upper anchors.

Make sure the stopper knot is untied in the other rope or it will jam in the upper anchors.

Before pulling, check that no twists, tangles, or knots exist in the rope being pulled through the rappel rings, or the rope may get stuck.

Before pulling, check that no twists, tangles, or knots exist in the rope being pulled through the rappel rings, or the rope may get stuck.

One climber pulls the rope down while the other pulls it through the new rappel rings until the midpoint or knot connecting the two ropes is set at the anchors.

One climber pulls the rope down while the other pulls it through the new rappel rings until the midpoint or knot connecting the two ropes is set at the anchors.

Make sure there is no way to drop the rope. Passing the rope through the rings and tying a stopper knot can be adequate provided the rings are smaller than the stopper knot; or just clip the rope into something before pulling it. Pull the rope at a steady pace to lessen the chance of getting the ropes stuck. If the rope is hard to pull due to rope drag, both climbers can pull together to retrieve the rope.

Make sure there is no way to drop the rope. Passing the rope through the rings and tying a stopper knot can be adequate provided the rings are smaller than the stopper knot; or just clip the rope into something before pulling it. Pull the rope at a steady pace to lessen the chance of getting the ropes stuck. If the rope is hard to pull due to rope drag, both climbers can pull together to retrieve the rope.

Just before the end of the rope slips through the rappel rings, yell, “Rope!”

Just before the end of the rope slips through the rappel rings, yell, “Rope!”

If the rock face below the upper anchors is clean, let the rope fall down to your station.

If the rock face below the upper anchors is clean, let the rope fall down to your station.

If you are concerned the rope may get caught on ledges, cracks, or other features, whip the rope hard outward and downward just before it falls. There’s a small risk that the end of the rope will spontaneously tie an overhand knot when it’s whipped, causing the rope to jam in the higher anchors, so allow the rope to fall when the rock is clean.

If you are concerned the rope may get caught on ledges, cracks, or other features, whip the rope hard outward and downward just before it falls. There’s a small risk that the end of the rope will spontaneously tie an overhand knot when it’s whipped, causing the rope to jam in the higher anchors, so allow the rope to fall when the rock is clean.

If possible, take cover as you pull the ropes, and watch for rockfall so you can dodge it if the rope knocks something loose.

If possible, take cover as you pull the ropes, and watch for rockfall so you can dodge it if the rope knocks something loose.

If there is no ledge at the anchors, you have a hanging rappel station. This does not change any of the steps described above. Simply clip into the anchors with the slings girth-hitched to your harness, then lean back and hang from them. Once the entire team is hanging from the anchors, pull the ropes down while rigging them for the next rappel.

Most of the time you can rappel straight down to the next station. But if the wall overhangs steeply, you could end up hanging in space, or spinning too far from the wall to reach the anchors.

For an overhanging rappel:

1.The first climber down clips the ropes into protection anchors every so often while rappelling, so she stays within reach of the wall. The more overhanging the wall, the more frequently she needs to clip the ropes.

2.The first climber can push off the wall with her feet to get swinging so she can reach in to the rock to clip bolts or place directional protection.

3.After arriving at the new anchors, the first climber down clips herself in and then ties the ropes into the anchors.

4.The last climber down unclips the protection and cleans it on his way down. When he arrives at the next station after cleaning all the protection, he will be hanging out in space. His partner then pulls him in to the station with the ropes.

5.The team needs to be careful about not losing control of the ropes. If you let go and they’re not tied in, they’ll swing out of reach and strand you.

Traversing rappels can be tricky—it’s much easier going straight down. The first climber can rappel while steadily working sideways toward the next station, using his feet on the wall to keep from swinging back into the fall line. If he traverses at too great of an angle, his feet will slip and he’ll swing violently sideways.

Another option is to rappel straight down until you’re slightly below the next rappel anchors, then pendulum (swing) over to them. Often this is easier than traversing for the entire rappel, but be wary of sharp edges that could damage the rope.

A third possibility is for the first climber down to set protection and clip the rope in as he rappels and traverses to help him reach the next anchors. The last climber down cleans these directionals and then gets pulled into the rappel station by the first climber, who has tied the ropes into the anchors.

Every climber should know one or two alternative rappelling methods in case they drop their rappel device. There are several methods for rappelling with only carabiners. The best two are the Munter hitch and the carabiner brake.

Tying a Munter hitch with both rope strands onto a pear-shaped carabiner is a quick and simple method for rappelling. Unfortunately, the Munter hitch may twist the ropes and promote kinking. Still, the Munter works nicely in a pinch for rappelling. Keep your brake hand directly below the hitch to minimize kinks. A rappel backup is recommended when rappelling with the Munter. See Chapter 4, Knots, for details on creating a Munter hitch.

Rappelling with a Munter hitch

The carabiner brake was a standard rappelling technique for many years until modern rappel devices came along. The carabiner brake is easy to rig with four standard carabiners and one locking carabiner. Most styles of carabiners work fine as long as they’re not too small or oddly shaped. The brake works best with four carabiners of the same shape.

To set up a carabiner rappel brake:

1.Clip a locking carabiner to your belay loop and lock it, or clip two nonlocking carabiners, with gates opposed and reversed.

2.Make a platform by clipping two carabiners onto the locking carabiner (or opposed carabiners) and oppose the gates (A).

3.Pass a bight of both rappel ropes up through the platform carabiners (B).

4.Clip a carabiner onto one side of the opposed carabiners with the gate facing down (C).

5.Pass the carabiner under the ropes and clip it to the other side of the opposed carabiners. The carabiner gate must be down, away from the ropes (D).

6.Clip a second carabiner onto the opposed carabiners exactly like the first one, with the gate facing away from the rope (E).

7.You can add a third carabiner to those rigged in steps 5 and 6 for increased friction with heavy loads, but two is usually fine.

8.Add the autoblock, and you are ready to rappel.

Getting your ropes stuck while rappelling is inconvenient at best, and potentially dangerous. Most stuck ropes can be avoided.

To minimize the chances of jamming your ropes:

Extend the rappel rings from the anchors so it lies below the ledge, unless the ledge is small.

Extend the rappel rings from the anchors so it lies below the ledge, unless the ledge is small.

Make sure the rope runs through metal rappel rings or carabiners. If the rope runs directly through webbing, it will be harder to pull.

Make sure the rope runs through metal rappel rings or carabiners. If the rope runs directly through webbing, it will be harder to pull.

Keep the rope out of cracks or other obstacles that might jam it or the knot. If you rappel first, warn your partners about any obstacles that you see.

Keep the rope out of cracks or other obstacles that might jam it or the knot. If you rappel first, warn your partners about any obstacles that you see.

Use the flat overhand knot for joining rappel ropes.

Use the flat overhand knot for joining rappel ropes.

Whip the rope hard downward and outward just after it falls through the rappel rings.

Whip the rope hard downward and outward just after it falls through the rappel rings.

Make shorter rappels if the terrain is highly featured—it’s faster than dealing with a stuck rope.

Make shorter rappels if the terrain is highly featured—it’s faster than dealing with a stuck rope.

Despite taking all the precautions, if you climb and descend multipitch routes, you will occasionally have to deal with stuck ropes.

If the ropes are hard to pull from the very beginning:

Try flipping the ropes away from any cracks or other obstacles that cause rope drag.

Try flipping the ropes away from any cracks or other obstacles that cause rope drag.

Make sure the ropes are not twisted around each other. Pull them apart and watch to see that they separate all the way to the anchors.

Make sure the ropes are not twisted around each other. Pull them apart and watch to see that they separate all the way to the anchors.

Try pulling on the other rope. It’s possible that you’re pulling on the wrong rope and the knot is jammed in the rappel ring.

Try pulling on the other rope. It’s possible that you’re pulling on the wrong rope and the knot is jammed in the rappel ring.

If you’re on the ground, walk out from the cliff to pull the ropes, or try pulling from a slightly different direction from the ground. This sometimes decreases the rope drag and enables you to pull the rope.

If you’re on the ground, walk out from the cliff to pull the ropes, or try pulling from a slightly different direction from the ground. This sometimes decreases the rope drag and enables you to pull the rope.

Pull harder. This may be a solution, but it also might jam the rope deeper in a crack.

Pull harder. This may be a solution, but it also might jam the rope deeper in a crack.

If the ropes stay jammed despite all your efforts, you may have to climb the ropes back to the rappel anchors to solve the problem. See Chapter 14, Climbing Safe, for directions on how to climb up the rope. Remember, the jam is not a proper anchor so it requires careful technique to ascend safely, and in some cases it may not be possible to ascend a stuck rope safely. If the rope cannot be freed safely, it is best to simply walk away (if you are on the ground), or if you are still above the ground cut the rope as high as you can safely reach and continue the descent with whatever rope you have left.

Rappelling is often the only and best option for descending, but it has many potential hazards. Good judgment, attention to details, awareness of hazards, and religious double-checking will help keep you alive.

Some of the hazards, and how to avoid them, are:

Getting hair or clothing caught in the rappel device: Keep all loose ends tucked neatly away or extend the device.

Getting hair or clothing caught in the rappel device: Keep all loose ends tucked neatly away or extend the device.

Rockfall: Falling rocks can hit you or

Rockfall: Falling rocks can hit you or

your ropes, and they can be triggered when you retrieve your rappel ropes. Wear a helmet, use an autoblock backup, and watch out for loose rocks. If multiple climbers will rappel, fix both rope strands for all but the last rappeller, to make the rappel ropes redundant. Tie a figure eight loop in both rope strands near the joining knot and clip them to the rappel anchors with a locking carabiner to fix the ropes.

Stuck ropes: A stuck rope can strand the climbing team unless they know how to climb the rope to fix it.

Stuck ropes: A stuck rope can strand the climbing team unless they know how to climb the rope to fix it.

Bad anchors: Most of the time you can beef up bad anchors by leaving some of your own gear behind.

Bad anchors: Most of the time you can beef up bad anchors by leaving some of your own gear behind.

Rappelling off the ends of the ropes: A stopper knot in the end of each rope can prevent this possibility if you are rappelling with a tube or plate device.

Rappelling off the ends of the ropes: A stopper knot in the end of each rope can prevent this possibility if you are rappelling with a tube or plate device.

Losing control of the rappel: An autoblock rappel backup makes it easier to maintain control.

Losing control of the rappel: An autoblock rappel backup makes it easier to maintain control.

Ropes don’t reach the next anchors: Research the rappel route ahead of time and make sure your ropes are long enough. If you can’t reach the anchors, it’s possible that you missed them on the way down. You may need to climb back up the rope to look for the anchors or set your own to continue.

Ropes don’t reach the next anchors: Research the rappel route ahead of time and make sure your ropes are long enough. If you can’t reach the anchors, it’s possible that you missed them on the way down. You may need to climb back up the rope to look for the anchors or set your own to continue.

Rappel device rigged wrong, possibly only on one strand of rope: The double-check ritual should discover any errors in the rigging.

Rappel device rigged wrong, possibly only on one strand of rope: The double-check ritual should discover any errors in the rigging.

EXERCISE: RAPPELLING EXPERIMENTS

Grab your climbing partner and find a short, steep cliff with easy access to the top. Gather together as many different rappel devices as you can find. Set a good rappel anchor and rig the rope to rappel. Set another rope for a top-rope belay, so you can practice rappelling with a top-rope for safety.

Set your device on the rappel ropes without a rappel backup and rappel to the ground. Imagine what will happen if somehow you let go of the rope.

Set your device and an autoblock rappel backup on the ropes. Rappel down partway, then let go of the autoblock to see if it locks onto the rope. Repeat rappelling and then locking the autoblock several times. The autoblock should allow you to rappel smoothly, and it should lock onto the rope whenever you release it.

Rappel with other devices and see which ones are easy to rig and which ones rappel smoothly.

Make a Munter hitch on the two strands of rappel rope, and clip it to your harness belay loop with a locking carabiner. Lock the carabiner. Add an autoblock and rappel. Note how the rope twists from the Munter hitch when the ropes are not parallel.

Rig a carabiner brake and rappel. Practice the rigging a few times so you can remember it if you ever drop your rappel device from a climb.