Lecture 10

12 JANUARY 1934 293

IN THE LAST LECTURE, we concluded our discussion of the “Seeress of Prevorst.” Her case illustrates the utmost introversion, in that everything moves inward. Everything in her has been cut off from our reality; indeed she defended herself against the outer world. To her, reality as we know it has been dispossessed of its meaning and emotional emphasis; instead, something unknown to us, about which we know only through legend, appears in her. To her, this background of the soul is plastic, and possesses all the meaning and emotional emphasis that reality has for us. Whereas human beings—some loved, others loathed—inhabit our world, ghosts populate hers. Where the sun or the moon shine in our world, in hers shine an inner sun and an inner moon.

Wherever and in whomever we find such pronounced introversion, we will also find indications of these phenomena. If we ask those people, they will deny it, and for several reasons. First, because they are shy of exposing themselves to ridicule by admitting to such experience; the Seeress, however, was too deeply convinced of the reality of her experiences to be troubled by such fears. Second, people are as a rule afraid of these things, for they have heard that they belong to the field of psychiatry. Third, because they are very often unconscious of these experiences, and as a consequence suffer indirectly from symptoms.

Whenever introversion intensifies, the three phenomena I mentioned become apparent:

1. Time and space become relative, presentiments and dreams come true, and telepathic experience occurs.

2. We find certain autonomous psychic contents, ultimately leading to personifications and the apparition of ghosts.

3. Symbols of a psychic center are experienced. This center does not coincide with consciousness, and is generally perceived as a source of life, equivalent to an experience of God. One can recognize therein the essence of religion.

The Seeress is most certainly a border case. While it is very rare to encounter such cases, quite a number of them have been recorded throughout history. In contrast, cases involving compensation are more frequent. These cases will not strike us as strange as the one we discussed, and we will see more clearly how familiar we all are with such experiences. If people are not destined to die in a state of complete introversion, a reaction will have set in, and a certain extraversion will become apparent. The background of the soul is clouded over, the energetic charge of the contents decreases, plasticity wanes, and the images become pallid and blurred. We find all indications of an outer reality that interferes with the background. The image of the background of the soul becomes translated into the banality of everyday life, and the spotlight of experience is directed elsewhere. We will consider the main stages of this process, not in regard to any particular case, but as I have been able to observe it generally.

In the first phase, the centerpoint vanishes, just as the sun-sphere did in the case of the Seeress. This vision of the sun grows dim. While it might remain intuited, it ceases to play a role. In many cases, it becomes unconscious. What remains is the intermediate realm of so-called ghosts and of those phenomena that manifest some uncertainty regarding time and space, that is, experiences of a telepathic nature.

In the second phase, the autonomous figures, namely, the personifications and ghosts, disappear. Presentiments and telepathic dreams continue to exist, as well as curious manifestations in consciousness that elude rational explanation. What is known appears strange; forgetfulness occurs, partial amnesia, and so forth. Only vestiges remain of the autonomous contents, which had previously become personified. Such phenomena can still be observed in primitives, who ascribe them to the presence of ghosts. It is always a ghost, a witch, or a sorcerer who takes something away from them. With the mentally ill, this condition is known as “thought withdrawal.”

The third phase occurs when the entire psychic background goes dark, that is, when nothing remains of these autonomous inner psychic phenomena. The person’s memory seems to be normal, and the psychic [autonomous inner] phenomena no longer seem to exist. Here we approach “normality.” The more manifest so-called normality becomes, the more a strange phenomenon occurs, namely a defensive attitude towards the matters of the background that no longer appear attractive. One is no longer tempted to have dreams and to experience the appearance of ghosts. The entire affair becomes uncanny, repugnant, repulsive, childish, ridiculous. Such people begin to build a thick wall of rationalist skepticism and “scientific” attitudes, and seal the entire matter airtight. If anything creeps through nonetheless, it is dismissed as “merely psychological.” This, however, prompts a true and proper witches’ sabbath of incompatible complexes. Consciousness grows too strong in proportion to the degree in which the background is walled off. Those people find themselves terribly interesting and important, and become most dreadful bores. It is nothing but an exaggeration, a showing off, but in a manner that has lost the characteristics of experience; it is a pumped-up story, something that is intended to impress. If such a condition persists, we speak of neurosis. An inflation of the subject occurs, and everything becomes psychologized. Since those people are wrong and actually know that they are, however, they become oversensitive—hypersensitivity is always suspicious!—and one has to walk on eggshells around them in order not to tread on their psychological toes.

This is an unfortunate intermediate condition that improves immediately, however, when extraversion actually commences, and all thought of the wall and world beyond is forgotten and obscured. Neurosis will then abate. Such a man no longer looks into himself, but turns to the conscious world with a sense of relief and freedom, and thus detaches himself from the background. His friends will push him still further along that path: he should meet people, he should travel, throw himself into something, he shouldn’t waste his time, but exercise his will, etc. Such people become veritable acrobats of the will. So-called objective values become increasingly persuasive, and it is extremely important to them to be normal and healthy. Such concepts are indeed effective—the concept of “normality” happens to be persuasive, although no one knows what “normal” means. The inner world is now completely darkened, and appears only here and there in the form of slight disturbances. “I feel absolutely terrific. I’m always happy, satisfied, etc.” Such an attitude of “healthy-mindedness” 294 is typical of Americans, and is based entirely on the extraverted principle. All goes swimmingly, he overflows with wonderful descriptions of his family and his enviable lot—till one day he appears with a face a yard long because he has had a bad dream, and something from behind the Great Wall has managed to slip through. Dreams are incursions from the hinterland, and the shadow announces itself. The closer people still are to that Great Wall, the better they hear what happens there—but then they immediately rationalize it again.

A patient once consulted me in precisely such a state of agitated extraversion. I advised him to spend an hour on his own every day. He was delighted at the thought, and said that he could now play the piano with his wife every day, or read, or write. But when I discarded each of these possibilities one after the other, and explained that he was to be really alone, he looked at me in despair and exclaimed: “But then I’d become melancholic!”

The next phase is complete extraversion. Here, we find the people who have already become quite identical with what they represent, and no longer with what they are. We often see this in people who have been successful, for example, the village or town mayor is nothing other than that. Such achievers live their roles day and night; they are already living their biographies as it were. They appear solemn, and radiate a persuasive dignity and conformity; everything is well balanced. It is actually the highest level of perfection on this way if someone becomes identical with the object, that is, with the light in which he wishes to appear. He doesn’t have a clue about his own subject, but has become completely absorbed in something else, and is no longer himself. He has devoted himself to something, and has now become that thing, his status, his profession, or his business. Individuals who thrive completely on an object have subjective motives.

There is a good story about a Basel parson which illustrates this condition admirably—psychology consists of good stories! He was full of zeal for the welfare of his congregation and eager to provide it with the recreation he felt it required, but he was poor—such people choose their parents badly and never have any money, they always have to beg it from others! On his rounds among the richer Basel citizens, he called on a very sarcastic professor of theology who was well furnished with this world’s goods. After much pleading, during which the professor remained unmoved, the parson leapt up in a rage, screaming: “D’r Herr will’s!” [The Lord wants it!] The professor, pointing at him, replied: “Der Herr will’s!” [This gentleman wants it]. This road leads to the illusion that what I, a lamentably small I, want, is the will of God.

This outward movement, however, is not entirely ridiculous, but is part of the birth process of man. Children and adolescents must forget the background. A child who remembers the background for too long would become inept at entering the world. Young people must erect many walls between the background and the subject so that they can believe in the world. Otherwise we would be unable to do anything. If we are anchored in the inner world, the values of the world will seem doubtful, and we will be unable to pull ourselves together for some real action. We will get lost in thoughts, and miss the right moments, or fail to attach to a given matter the vital importance it actually has. Many become procrastinators because they are anchored too much in the background, and can no longer summon faith in what matters. To be wholly devoted to something is also an art and something good, in particular for young people.

For young people, this is absolutely important. It is true, however, that there are also young people who are philosophically or religiously minded, and those should indeed know that something else exists, too, and that one should not live only outward. For if they misplace the values that belong in the background and move them to foreground, their world view will become distorted. Many difficulties arise from the fact that relationships and values are treated with an importance they do not deserve. For instance, Mr. So-and-so said this and that about me. I could take terrible offence. This, however, would be ridiculous, and not worth dwelling upon. For what have we said about others!

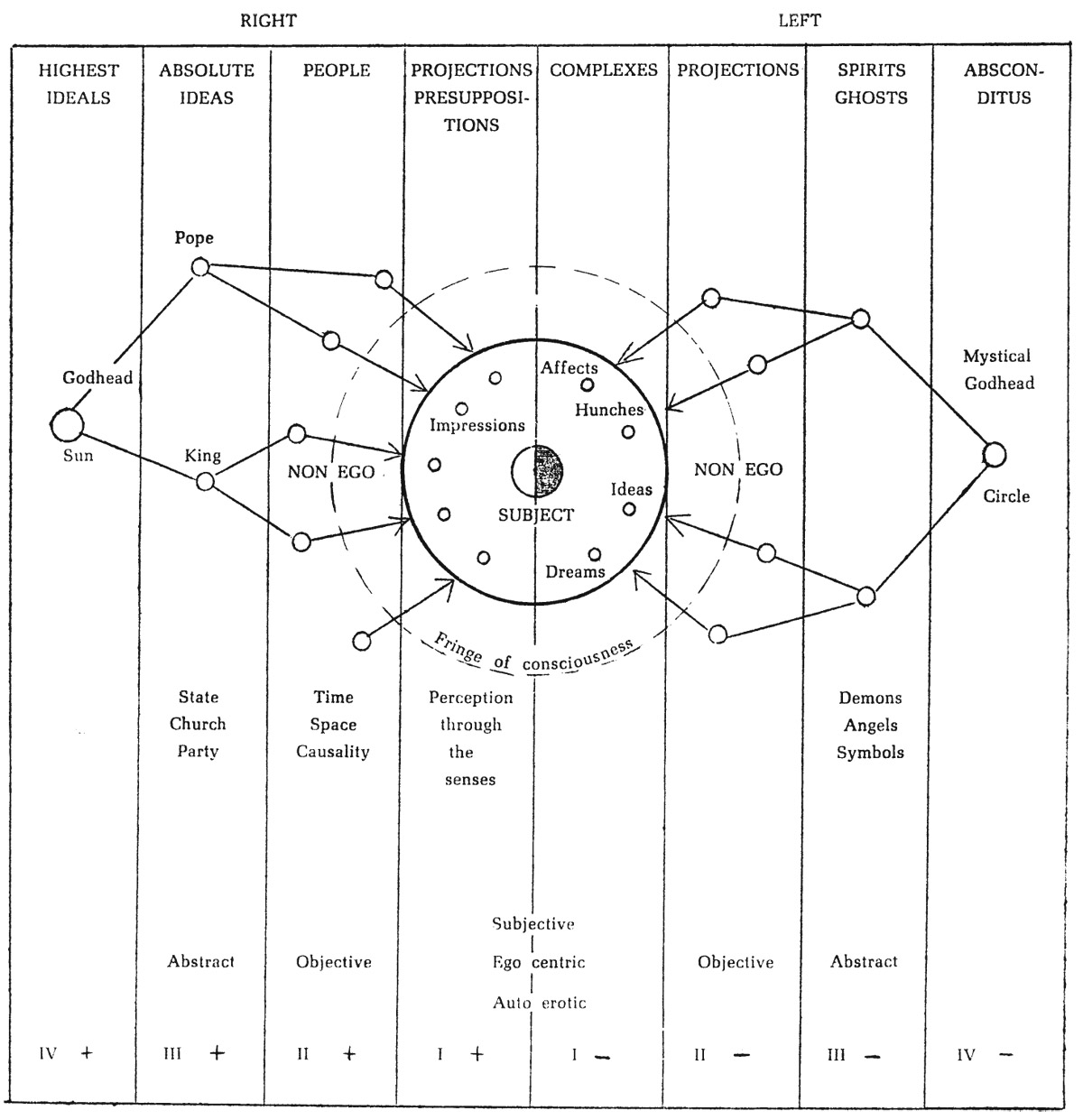

I would like to illustrate this outward development with a diagram. 295

The right side illustrates how this development unfolds in the outer world, as I have discussed in this lecture. The centerpoint is the subject, to which everything else refers.

293. Sidler noted that he had to miss this lecture due to tonsillitis, so the compiled text of this lecture is based on the notes by M. J. Schmid, R. Schärf, and B. Hannah.

294. This expression, probably referring to William James’s concept of “healthy-mindedness,” is in English in the German lecture notes.

295. Hannah places this passage and the diagram at the beginning of the next lecture, dated 19 January 1934.