Lecture 11

19 JANUARY 1934 296

SUBMITTED QUESTIONS

There is a query from one gentleman regarding the mandalas discussed at the end of the last lecture. I shall explain it to him after today’s lecture. 297

***

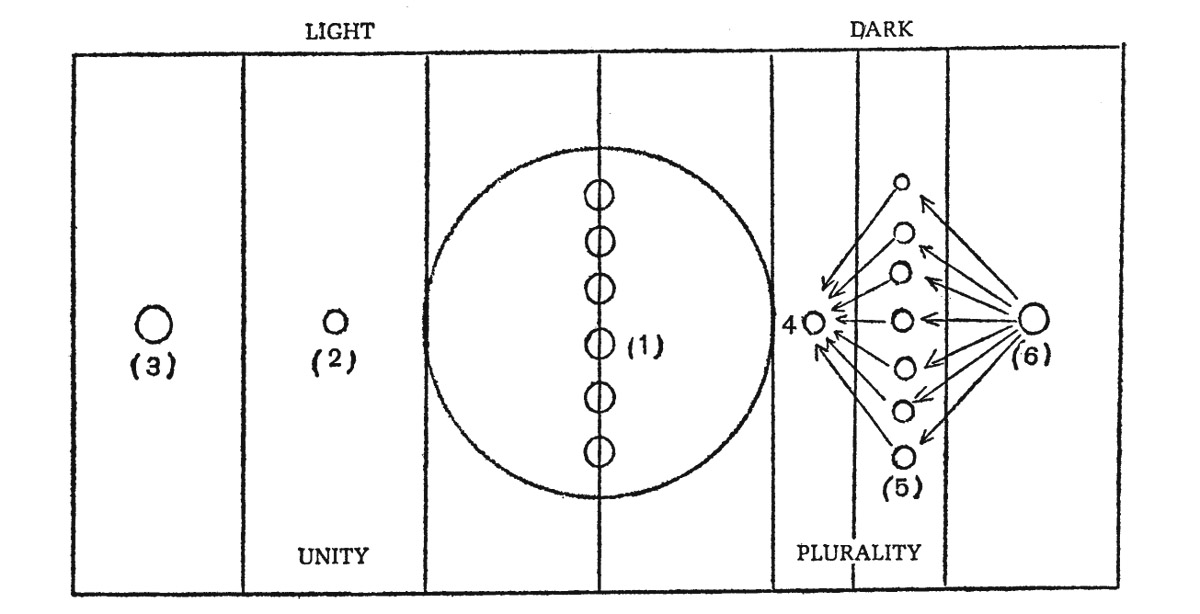

Today, I would first like to make some further remarks on the diagram that I presented last week.

RIGHT SIDE OF THE DIAGRAM

The impressions of our surroundings that we perceive are not simply the objects themselves, but what we perceive are the images of these objects and persons. We perceive things as they appear to us, and we are always caught in subjective prejudices that distort and disturb our perceptions. For instance, “Mr. X makes an excellent impression on me—but not on my friend.” Or “I find the painting very nice, but my friend thinks it’s dreadful.” It is as if we were surrounded by an oddly deceptive fog through which we perceive things, and which affects our perception in a peculiar way. No human can escape this. It is the greatest possible art to observe objectively. We probably observe rather precisely things that are indifferent to us, but in the case of things that concern us personally the fog gets thicker.

Why is this so? We have unconscious presuppositions or false associations. A female patient once told me: “My doctor strongly objects to my consulting you.” “How so, I don’t even know this gentleman. What did he tell you?” “I don’t know.” “Well, did he tell you directly?” “No, but I could tell.” “How so?” “He said: ‘What’s this, you intend to consult that mad baldhead?!’” Clearly, the man must have had an utterly wrong notion of me when he called me baldheaded! 298 William James refers to the fog that surrounds us as the “fringe of consciousness.” 299

The further things lie from us, the more objective we can be. In the sphere of abstract ideas (III), an impersonal or not-I way of looking at things exists, which is quite free from subjective prejudice. It is impossible to live entirely in the personal attitude, because the nonpersonal catches us somehow. We need both the personal and the impersonal point of view. To approach the Divinity has always been felt as an escape from the futility of personal existence. I once saw something very touching in the newly excavated tomb of a pharaoh: a little basket made of reeds stood in a corner and in it lay the body of a baby. A workman had evidently slipped it in at the last minute before the tomb was sealed up. He himself was living out his life of drudgery, but he hoped that his child would climb with the Pharaoh into the ship of Ra and reach the sun. 300

But the personal element is also necessary in life. A woman once came to me absolutely broken down because her dog had died. She had drifted away from all human contact, the dog was her only relationship; when it disappeared, she went to pieces. The primitive makes no distinction between the personal and impersonal. L’état c’est moi, as Louis XIV said, 301 and that is just how the primitive king looks upon his kingdom.

Nature simply produces something; she never tells us her laws. It is human intelligence that discovers them and makes abstractions and classifications. In the abstract sphere (III), things and persons are classified by their sex, age, family, tribe, race, people, language, and settlement area; and thereafter by occupation, and by psychological and anthropological types. These are so-called natural classes, which, however, also correspond to an abstraction, so they belong to Section III + in the diagram. Abstractions can become more important than the human unit; it is a question here of “how many?”, not of “who?”

The abstract sphere also contains purely ideational groups, which are characterized by a particular idea, such as the state, the Church, political parties, religions, various -isms, societies, and so forth. They usually possess a symbol, for example, the ideational group of the Swiss fatherland is symbolized by a white cross against a red background, or take the cross as the Christian symbol, the half-moon, the Soviet star, and the swastika. Or the totem animals of the nations, such as the Prussian eagle, the British lion, or the Gallic cock. Kings wear the crown, the corona, and the coronation mantle, the astral sphere. The old German emperor holds a globus cruciger in his hand, the symbol of earthly power. These are all astral, cosmic symbols. These ideational groups deny any purely natural descent, but instead claim to stem from the most exclusive and oldest ancestor: the sun. Symbols such as the sun symbol belong to the sphere of highest ideals (IV +); the sun often symbolizes the father, the life giver. This brings us to the end of the right side of the diagram, the side of consciousness.

LEFT SIDE OF THE DIAGRAM

But how are things on the other side, the backside? We have already discovered that we have a shadow side, too, a “behind.” This is something that we leave in the shadows, that we prefer to leave untouched, except perhaps under particular circumstances, such as when we go to confession, or when someone “professes” his allegiance to the Salvation Army. 302

Certain contents may surface. You might, for instance, awaken in a terrible mood: “What’s wrong with you?” “Nothing at all!” Within the “fringe of consciousness” lies the province of projections, of affects, and of inexplicable moods. We are also blessed with ideas or, if you want to put it more nobly, with inspirations. The Americans have a good word in this respect: to have a hunch, 303 that is, a humped or crooked position. And, obviously we have dreams, too.

Let us now proceed somewhat further. Just let us assume, as a working hypothesis, that things in this sphere of unconscious presuppositions are not quite the same as on the other side. It is not likely that ideas spring from the aether, but they are based on underlying psychological material. Likewise dreams: in analyzing them, we discover all kinds of material that was previously unconscious. Let us make another hypothesis, namely, that these unconscious presuppositions distort affects and ideas in the same way in which the fog distorts perceptions on the other side.

Now something analogous ought to correspond to people and things on the other side, and these are the phantoms and ghosts. It is the ghosts that cause those affects, ideas, or dreams, and they might also explain why we awaken in a certain mood. This is really the case in primitives and the mentally ill. The primitive has a better realization of the autonomy of this inner side than we have. He does not speak of having a mood, but of being possessed by one. So he does not say, “I am angry (or sad),” but instead “I have been made angry (or sad),” or “I have been shot at.” Likewise, the mentally ill exclaim, “X-rays shot this through me.” “They,” the spirits or ghosts, steal the primitive’s soul away and make him ill, so he knows that he has to work day and night to remain aware of them and keep them at bay. There is a native tribe in Australia that, even when temperatures drop to two degrees Celsius below zero, will lie naked beside the cold fire, freezing stiff. But they would never dream of covering themselves with furs and blankets! One tribe actually spends two-thirds of its time fighting the magic influences of evil demons! But you try telling any of them that this is nonsense! I would advise you not to! I once tried—and my successor, who also tried, was spiked with spears!

We saw that the Seeress’s world was peopled with ghosts, just as the outer world is inhabited by real people and objects. So the spirit world is the complete equivalent of the outer world on the other side of the diagram. For us, this sounds like a crazy story; this is something that leads us deep into the primordial world. Like the people in the outer world, ghosts form groups, too. For example, the Church organizes its angels in a celestial hierarchy of nine orders and three groups, this hierarchy reaching its zenith in the Godhead. 304 Two hundred years ago, the world of demons was still alive for us. For Paracelsus, this was still a world of realities. But also for many people living in our mountains, these things are still real. So when a mountain farmer notices one day that his cow is giving less milk than usual, he immediately runs to the Capuchin monk to fetch a prayer card of Saint Anthony. 305 The next day, the cow might in fact give again as much milk as before. The farmer, however, tells no one that he has been to see the monk; on the contrary, should anyone inquire whether he believes in demons or ghosts, he will laugh and exclaim: “Oh no, what nonsense!” But he says this only because he is seeking election to the local council.

With primitives, things are quite different. I discussed these matters at length with a tribe in Central Africa that I once stayed with. 306 Our discussion afforded me highly interesting insights, which the relevant literature confirmed also for many other peoples. For here we are at once confronted with a peculiar problem, because in primitives the center, the I, is obviously missing; in its place there is a plurality, a multiplicity. This is due to the unconscious identity, the participation mystique, of primitives with each other and with objects. 307 The tribe comes to stand for the “I.” This accounts for the strange nature of their customs, such as the following: A horse has been stolen. The medicine man summons all male members of the tribe, has them stand in a circle, sniffs at each of them, and ultimately says to one of them that he is the thief. The latter acquiesces to this procedure without protest, and is put to death. Because being a member of the same tribe he, too, could have been the thief, even if was innocent in this particular instance.

Their own personal life means very little to them, a native will even commit suicide in order that his ghost may haunt the thief who has robbed him, for example: Someone seizes a weaker man’s planting patch, who thereafter threatens to take his life and haunt the perpetrator in the guise of a spirit. Often, the thief subsequently returns the land. Just as often, however, avarice proves to be stronger, so that the victim of the theft climbs up a tall tree and leaps to his death.

These people can readily identify with one another and transfer something onto someone else. Thus the field of human objects is missing in a way, because it is already contained in one’s own I-plurality. It is as if you observed a school of black fish in the water: when one of them suddenly changes direction, all the others do so as well. Therefore, they possess a veritable group consciousness that reacts as if the whole group had been affected. That is why they are easily given to panics like the “stampedes” of wild herds. They possess a pronounced “mob psychology.” 308

The individual is only the whole. They do not reflect upon themselves, thus making it difficult for us to get along with them. When one primitive adopted a position like Rodin’s “Thinker,” 309 he was asked, “What are you thinking about?” He jumped up furiously, and exclaimed, “But I am not thinking at all!” Primitives do have dreams, but are not really conscious of them. 310 Just as if I were to ask you here whether you have any religious customs? “Of course not!” you might exclaim. But then I happen to visit you at Easter and you are just hiding eggs in the grass. “Well, it’s just what one does!” One scholar once observed, “This goes to show how primitive these [indigenous] people are. They don’t even know what they are doing!” But do you know what the meaning of an Easter bunny or a Christmas tree is? None whatsoever! Nothing other than: “Well, it’s always been what people do.” 311

But one matter is certain: these people have a classification system. One man stands out: the chief. Members of the tribe stand side by side, but the chief does not belong in this row. He possesses “mana.” He stands before the people. A medicine man from a tribe in Central Africa 312 once told me in a palaver about the position of the chief compared to the other members of the tribe. In doing so, he used a bundle of small sticks, which always accompany a proper palaver—for each affair discussed, a small stick is stuck in the ground. “The chief is like this . . .” he said and placed one small stick in the ground, “and the others are like this . . .”—and he placed the remaining sticks in the ground in a row. “The chief has mana.” 313 The chief thus equals the king.

Primitives are unaware of their own “I.” There are many people among us, however, who are also unaware of their own I. Many neurotics have no consciousness of their I at all and are completely identified with their environment. “Oh, what would my parents say?” Or their aunt or anyone else for that matter. Their only standard is what others think, but it never occurs to them what they themselves might think about it. A young lawyer once said to me, “You know, one can do anything provided other people don’t know it.” Now, this fellow was unaware of his own moral motive, because he had no knowledge of it whatsoever.

When we come back to the dark side of the diagram, there is again an empty circle because the I is missing, but further back a single figure stands out again: the medicine man, who has immense influence as the interpreter of the spirit world from which he draws his power. Actually, this dark sphere has no definite and separate existence, because we are at a loss to say if the right side has been taken for the real side, or the other way around. Reality is probably rather in the background, because the latter is much more differentiated. With primitives, it is never clear whether this is a dream or reality. For example, a native had a dreadful nightmare. He dreamt that he was captured by his adversaries and burned alive. The next morning, he demanded that his relatives burn him alive. They refused at first; ultimately they agreed to tie him up, and to lower him into the fire by his feet. Thereafter, he hobbled around for nine months until the burns had healed—and all for fear of the dream. 314

There is a multitude of ghosts, who are all connected with the dark principle. This dark principle is ayík. 315 When I tried to speak to the natives of this dark God as of a second God, they protested: “No, there is only one God!” Then I realized that only one reigned at a time: From six o’clock in the morning to six o’clock in the evening, adhísta, the benign God, the good and bright spirit, rules; and from six o’clock in the evening to six o’clock in the morning rules ayík, the uncanny, dark, evil God. What is true for the day is reversed at night. Beauty abides by day while terror prevails at night. This is due to the fact that when you bask in the tropical sunshine, after a while you will feel as though you were drunk. When the outdoor temperature exceeds your body temperature, you will find it increasingly difficult to imagine anything unpleasant that could really agitate you. You become indifferent to everything. I experienced this myself in Africa as I lay in my hammock, hardly finding the energy to light a pipe. I thought hard of all my most depressing problems to see if they would affect me, but I remained absolutely indifferent. 316 No sooner has the sun gone down, however, than this optimism of the day immediately keels over into the absolute pessimism of the night.

296. R. Schärf’s typescript of this lecture is missing.

297. “Zurich, 19 January 1934

Dear Doctor!

At the end of the next-to-last lecture you quickly went over the contents of the various mandalas. As it went so fast, however, I could not keep up with my note taking, and my notes on the descriptions of the ancient Maya and Indian mandalas, as well as of the conversation between the pupil and the master (Upanishads), are incomplete. I would be very grateful, therefore, if you could again briefly describe the contents of these mandalas, perhaps also that of the Egyptian mandala, at the beginning of the next lecture.

Since the majority of your listeners did not hear your explanations at all, because they had to leave after 7 p.m., I think this would be of interest to others, too.

With many thanks and best wishes,

Arthur Curti” (ETH Archives).

298. Sidler notes here: “As if by accident, Jung turned the back of his head towards us to reveal his bald patch.”

299. “Let us use the words psychic overtone, suffusion, or fringe, to designate the influence of a faint brain-process upon our thought, as it makes it aware of relations and objects but dimly perceived” (James, 1890a, p. 258; on “fringe of consciousness,” see p. 686).

300. Jung tells the same story (although in a slightly different version) in 1939b, § 239.

301. “I am the state,” the maxim of absolutism, probably falsely attributed to Louis XIV of France (1638–1715).

302. A Salvationist Soldier has to sign the Salvation Army Articles of War, expressing his commitment to live for God, to abstain from alcohol, tobacco, and from anything that could make his body, soul, or mind addicted, as well as expressing his commitment to the ministry and work of a local Salvation Army corps.

303. This expression in English in the German notes.

304. The Catholic Church distinguishes between nine levels, or choirs, of angels (Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels, and Angels), organized in three triads, or spheres.

305. This is known as Saint Anthony’s “Brief” or “Letter,” which he allegedly gave to a woman who wanted to drown herself, thereby freeing her from demonic oppression and the desire to do away with herself. It contains the following exorcism: Ecce crucem Domini! Fugite partes adversae! Vicit Leo de tribu Juda, radix David. Alleluia! [Behold the Cross of the Lord! Flee ye adversaries! The Lion of the Tribe of Juda, the Root [son] of David, has conquered. Halleluia!]

306. The Elgonyi in Kenya, in 1925/1926. See Jung’s description of this trip in Memories, chapter IX, iii, which also gives more detailed accounts of some of the experiences mentioned in this lecture.

307. Jung’s work abounds with references to Lévy-Bruhl’s notion of participation mystique, or mystical participation: “It denotes a peculiar kind of psychological connection with objects, and consists in the fact that the subject cannot clearly distinguish himself from the object but is bound to it by a direct relationship which amounts to partial identity” (Types, Definitions, no. 40).

308. “Stampedes” and “mob psychology” in English in the original notes.

309. The famous bronze sculpture by Auguste Rodin (1840–1917).

310. Jung also mentions this episode in the summer semester of 1934; see Volume 2 (forthcoming).

311. These are favorite examples of Jung’s to show that archetypal images “had simply been accepted without question and without reflection, much as everyone decorates Christmas trees or hides Easter eggs without ever knowing what these customs mean. The fact is that archetypal images are so packed with meaning that people never think of asking what they really do mean” (Jung, 1934b, § 22).

312. So Sidler; according to the notes of M.-J. Schmid, it is the chief himself, not the medicine man, who explains these matters.

313. Sidler noted here: “Also see the chapter ‘Archaic Man’ in Dr. Jung’s book, Seelenprobleme der Gegenwart, Verlag Rascher, Zürich” [1931b]].

314. Jung had read this story in Lévy-Bruhl (1910, p. 54), who himself had quoted the Jesuit missionary Père Laul Lejeune and his Relations de la Nouvelle France. Jung told this story also elsewhere (1928, § 94), but in both instances embellished it somewhat—there is no mentioning in Lejeune of relatives, or that they at first refused to burn the dreamer, and it took him six months, not nine, to recover: Un [primitive], ne croyant pas que ce fût assez déférer à son songe que de se faire brûler en effigie, voulut qu’on lui appliquât réellement le feu aux jambes de la même façon qu’on fait aux captifs, quand on commence leur dernier supplice. . . . Il lui fallut six mois pour se guérir des ses brûlures [A primitive who believed that in order to comply with his dream it would not be enough to burn himself in effigy, requested that his legs be actually burned in fire, in the same way as one started to burn prisoners to death. . . . It took him six months to recover from his burns].

315. Sidler notes: “the word expresses a sudden cold gust of wind.”

316. Jung recounted this also in the German Seminar of 1931: “The indigenous people lie around in the sun as if they were drunk. I observed this intoxicating effect of the tropical sun in myself: one is no longer touched by anything unpleasant, and is overcome by boundless indolence. (For example, I could observe, with the watch in my hand, that it took me a whole hour to reach the decision to light my filled pipe.) The climate produces an immense optimism” (forthcoming).