Lecture 13

2 FEBRUARY 1934

SUBMITTED QUESTIONS

I have received a few reactions, probably from some of the younger members of the audience, 328 wishing me to present fewer case histories, and instead give you more of my own point of view. Now I consider that I have done this pretty freely already, but you must bear in mind that I set out to give a course of lectures on modern psychology, and I cannot claim that modern psychology is identical with myself. It would be most immodest if I advanced my own views and opinions more than I already have. On the other hand, such factual material is an indispensible component of such lectures; we have to deal with the whole of the human soul, and we must remain close to everyday life so as not to get lost in cold theories. So if we discussed solely the problem of the transcendent function, 329 for instance, we would all be parched from too much spirit. Compare the study of anatomy: presumably, we must take into consideration the entire human body rather than limit ourselves to one opinion about it.

I should like to repeat that the cases that we have been discussing are not unique or abnormal, as some of my audience still seem to think, but typical. If you dissect a salmon in a laboratory, you are not studying one salmon in particular, but simply the salmon. So these experiences lie more or less hidden in the unconscious of ordinary people. But it is true that very few are able to actually have these experiences, and so it is an exceedingly difficult task to make them comprehensible. My psychology comprises, after all, quite a number of concepts that are underpinned by experiences that are not generally accessible. If one posits a very general claim, which has been verified in many instances, one can always hear people exclaim, “Well, quite the contrary is true in my case!” If you seek to explain to such people why their case is different, you will need half their life story. Consequently, I must set out some fairly broad factual material. This is a necessary prerequisite for the study of modern psychology, for these are cases that render visible what is invisible in your specific case. Such things do occur, however, and we must therefore take them into account.

***

Let us now return to our case and to the figure that I started discussing in the last lecture. We encountered a male figure named “Léopold,” a kind of protective spirit, an animated shadow, that acts of his own accord, and from time to time intervenes in critical situations, which is referred to as a “teleological automatism.” 330 This is a scientific term, however, that is somewhat too general. This helpful or disruptive intervention shows intention and intelligence, and thus cannot be considered an automatism.

This figure had not existed before Flournoy began observing Hélène. Victor Hugo existed beforehand, and the figure of Léopold emerged only later. At one of the séances of the Group N., Hélène had a vision of a conjuror showing her a carafe of water and pointing at it with a small magic wand. 331 One of the members of the circle interpreted this figure as “Balsamo”—which is another name for “Cagliostro,” since this very scène de la carafe occurs in a novel by Alexandre Dumas père, Mémoires d’un Médecin, Josef Balsamo. 332 The protective spirit himself added that “Léopold” would only be his pseudonym, and that in reality he would be Balsamo or Cagliostro, under which name this famous eighteenth-century magician and impostor had fooled the world. This episode then gave rise to an entire novel. Hélène imagined that she had been Balsamo’s medium, Lorenza Feliciani, in a prior existence, and would now be her reincarnation. It turned out, however, that such a figure had never existed in reality, but had been invented by Dumas. Léopold then explained that she would have actually been Marie Antoinette, which again refers to the scène de la carafe. 333 This episode in Dumas’s novel describes an accidental meeting between Balsamo and Marie Antoinette of Austria at the castle of Taverney, where she stayed on her way to Paris. She had been told that he could tell the future from a glass of water. Scrying is used all over the world, by the way, also by primitives, to inspire intuitions. So Balsamo looks into the carafe and sees her destiny, but refuses to tell Marie Antoinette what he had seen. Upon her steadfast insistence, he eventually yields and tells her to kneel before the glass and look into the carafe after he had waved his wand over it. She has a dreadful vision: she sees her own execution and faints. Hélène believes that she is a reincarnation of Marie Antoinette, whereupon a love affair ensues between Balsamo / Léopold and Marie Antoinette / Hélène; however, this is not borne out by historical evidence.

Flournoy was preoccupied with the name of Léopold, and justly so, because such names often have a deeper meaning. A colleague drew his attention to the fact that “Léopold” contains three consonants, LPD, and that the same three letters represented the initials of the motto of the Illuminati, a secret society: lilia pedibus destrue, “destroy the lilies with your feet.” In the beginning of his novel, Dumas describes a gathering of Illuminati and Freemasons from a great many countries on Mount Donnersberg near the German town of Mainz in May 1770, presided by the famous visionary Emanuel Swedenborg. 334 A stranger appears and asks to be admitted to the society. He then reveals himself to them as celui qui est, “The One Who Is.” The president confirms that the stranger is the “Illuminated One,” since he bears the three letters—“L.P.D.”—on his chest. The envoys of all countries recognize him as their leader and await his instructions. With their assistance, he intends to overthrow the monarchy within twenty years, and to establish a new world order. To this end all envoys must follow the motto lilia pedibus destrue in their home countries, that is, destroy the lily, the emblem of the Bourbon monarchy. The Illuminated One himself travels to France, where he begins to prepare the Revolution. 335

Historically speaking, this is not quite accurate. The gathering is antedated, since the order of the Illuminati was not in actual fact founded until 1 May 1776—namely, by Adam Weishaupt, a former Jesuit who later became a Freemason. 336 The society sought to pursue the ideas of the Enlightenment, and to bring about liberalism and free-thinking, bringing it in conflict with the prevailing social order, and the Illuminati were subject to frequent persecution. One of Weishaupt’s first collaborators, by the way, was Baron Knigge, the author of the famous book, On Human Relations. 337 Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the movement abated until its revival in Germany in 1880.

These literary parallels could leave us cold, if they were not psychologically meaningful, that is, symbolic. Seen in this context, it becomes clear that this spiritual leader or mentor, “Léopold,” actually is a member of a secret order, that is, an association of unknown leading thinkers. It is significant that they were Illuminati, because their member lists contained all sorts of famous names, like Herder 338 and Goethe. This is an important psychological criterion, for Léopold represents not a unity but a multiplicity. He has replaced neither Victor Hugo nor Balsamo, but represents all of them: he is the poet, the magician, and the member of a secret order. When he was asked himself about the origin of his name, he replied that he had taken it from a friend who belonged to the House of Austria. 339

In the course of subsequent meetings, he acquired a particular technique: he would take hold of the medium’s hand, and while séance participants were speaking to her, he would write with her hand. Often a long struggle ensued over the control of the hand, because Léopold would hold the pencil between the thumb and the index finger, whereas she always held it between the middle and the index finger. 340 Eventually Léopold would gain the upper hand. His writing also differed from the medium’s: he used obsolete eighteenth-century handwriting and spelling, although Cagliostro’s original handwriting bears no resemblance to Léopold’s. The same happened to the voice: although Léopold could neither speak nor understand a word of Italian, he spoke with a coarse Italian accent. Hélène’s own voice was not deep, but he taught her how to speak in a deep voice.

Interestingly, he always gave evasive answers to precise questions, whereas he flowed over with moral and philosophical talk, and wrote verse in the manner of a “Victor Hugo inférieur.” His memory was better than Hélène’s, in particular for certain data and other matters that usually easily escape one. Repeatedly, Hélène felt to be actually identical with him. Although he behaved differently, she often felt as if this figure had entered her being and overwhelmed it, resulting in a loss of her identity, in particular at night and in the early hours of the morning. The two states of consciousness were not completely separate, and Hélène and Léopold shared certain peculiarities, for instance animosity. Hélène was rather nervous and easily excited. Cagliostro/Léopold had quite a temper, was choleric, sometimes most unpleasantly brusque, and irritable, and also overtly enamored of himself. He was steeped in forthright animosity, and claimed to be an authority in all possible areas—and in those areas where he was not, he overrode his uncertainty with even more assertive statements. In particular, in the guise of Balsamo he prided himself on being a physician and alchemist who knew about elixirs and secret remedies. Many people consulted him through Hélène, although he affected a great disdain for modern medicine, and his prescriptions were as antiquated as his spelling. It then turned out that Hélène’s mother was well versed in the curative powers of herbs and plants.

Léopold’s tender love for Marie Antoinette, that is, Hélène, played a great role. He wrote her affectionate letters and poems. Curiously, he also felt affectionate towards Flournoy, referring to him as mon ami, my friend. He and Hélène were Siamese twins in a sense, since she, too, had tender feelings for her doctor, although she was not aware of this. On the other hand, Léopold was dreadfully jealous, and made Hélène the most amazing scenes when a male member of the group paid her any attention. Flournoy says of him: ce mentor austère et rigide, . . . présente, en somme, une donnée psychologique très générale; il n’y a aucune âme féminine bien née qui ne le porte logé dans un de ses recoins. 341 Her letters also attest to her peculiar affinity with this figure: all of a sudden, a word or a whole sentence would appear in his handwriting, and in antiquated French. And he also appeared in her dreams.

For the moment, I shall not continue with my description of this figure’s character. Pursuant to your requests, I shall instead set forth my own views. This figure is by no means unique, on the contrary it is very quite common, only we do not often see it in such a definite form. Flournoy’s description is classical. Although he had no idea of what he was describing, he intuited something, and gave a most clear description of the case. It is a typical and universal figure which I have called the “animus,” and no woman exists who does not possess it. I know of only one case where this figure was absent, and this was a militant suffragette, a friend of Mrs. Pankhurst’s. 342 She did not have this figure because she was it herself! The only other case that I recall was a hermaphrodite who came to me because she was in doubt as to whether she should live her life as a man or a woman. However, the number of those is legion who lack any knowledge of this figure. It is very difficult to point it out in many women because it is not clearly dissociated, but remains utterly in the dark and so naturally manifests itself only indirectly. One must turn to the shadow consciousness 343 to prove the existence of this figure. To do so, I must draw another diagram on the board. I am not sure whether it will meet with your approval, but so be it.

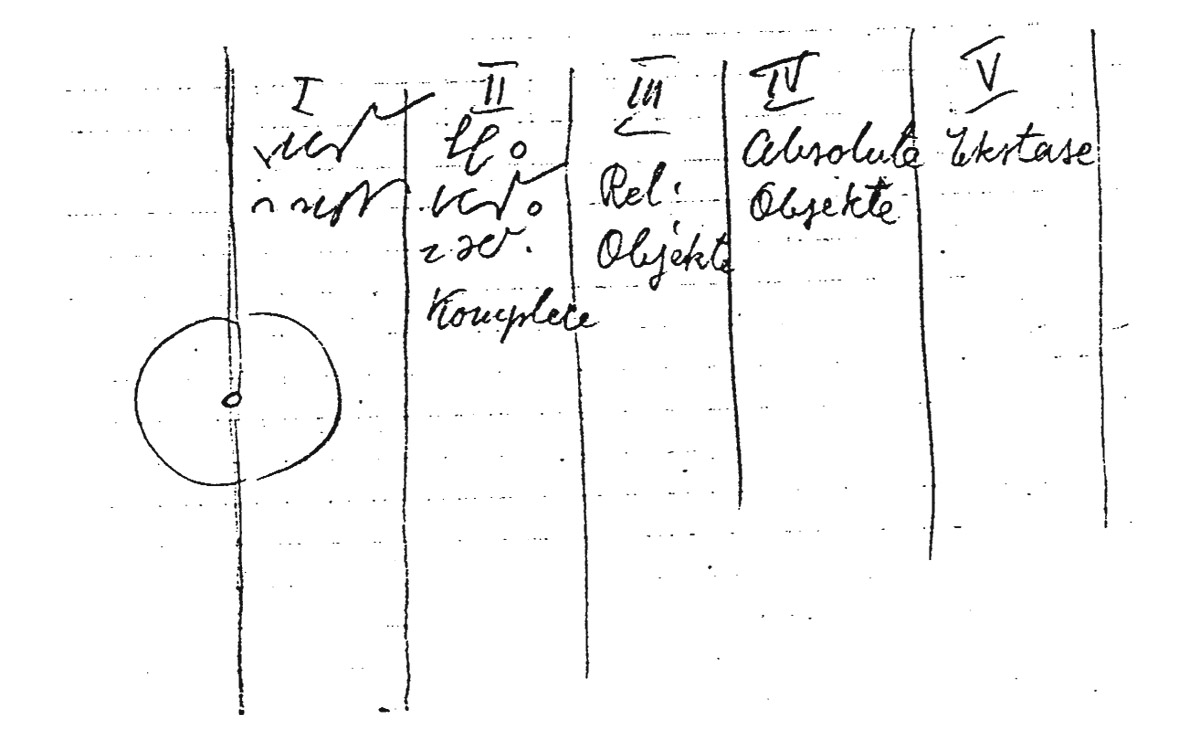

I: Unconsciousness of the subject; II: Stage of consciousness of the contents; complexes; III: Religious objects; IV: Absolute Objects; V: Ecstasy

We can differentiate between five spheres or stages. In the first sphere the “shadow consciousness” begins to make itself felt. In most persons it manifests itself as a slight feeling of missing something, or that something is not quite as it should be, as a léger sentiment d’incomplétude, 344 which gives rise to self-consciousness and a sense of inferiority. People look for the cause of this disturbing feeling in the outer world; they think perhaps their collar is crumpled or their tie crooked. Or a scholar has inferiority feelings because he feels his latest book is not quite as good as he thought, but will be terribly touchy should someone else criticize it. A tenor, of course, will have symptoms in the larynx, and an officer of the infantry in the feet. They place the inferiority where they really need not fear criticism; but in analysis I have to show them that their real inferiority lies somewhere else entirely. What we lack is never what we think it is, just as neurotic inferiority feelings never spring from where we claim they come from, but from real inferiority.

If the light of consciousness falls onto the right side, only a strange unawareness of subjective motives exists, a feeling of a certain darkness and a faint sentiment d’incomplétude. These people believe that all is well in their lives, and they have implicit faith in their good intentions: “All I ever wanted was the best.” They come to me with a glowing description of their ideal marriage and happy circumstances; yet I know that a neurosis has brought them, and why should they be neurotic if the conditions of their life are so perfect? These are the people who have no knowledge that this is the place where it is dark.

In the analytical sessions, I slowly move the light of consciousness to the left side, as I endeavor to make each successive sphere conscious. In the first hour, for instance, the light of consciousness moves only into a tiny fraction of the next stage, in the following hour a bit further, and so on.

Even though the shadow makes itself already felt in stage I, the focus of attention is still on the I. When the field of consciousness is limited, the body plays a great role. People who are enamored by themselves are extremely conscious of their bodies, they attach tremendous importance to how they have eaten, slept, digested, and what impression they have made on others. They tend to connect their complexes with the body; inner conflicts appear to them in the form of physical illness. They are egocentric and feel inferior, but dwelling so much on themselves may at least give them some idea of their shadow and their field of consciousness thus tends to become less restricted.

In the second stage the body is still important, but we find not only one object as in stage I, but a number of objects, namely, inner objects. People realize the existence of complexes that are independent of their own I. During the treatment, the light of consciousness shifts further from the right to the left side.

In the third stage something strange happens. People with a very limited range of consciousness, that is, very egocentric people, who have actually never been interested in anything else but themselves, are in fact clearly conscious of their shadow. They can provide you with an excellent description of themselves—if only it were interesting! At this stage, a realization of the contents of the complexes occurs, and they appear as independent, autonomous contents. An altered sense of the body relativizes the objectification; Léopold, for instance, is a relative objectivation. You have seen how this figure overlaps with Miss Smith, and is subjectively tainted by her temperament, character, her view of life, etc.

In the fourth stage, absolute objectivation occurs. In parapsychology, this is to be taken literally. The figures detach themselves and act autonomously, like persons that exist outside of us. These figures have their own will and intentions, and strike us as strange. In the case of the Seeress of Prevorst, for example, the priest is a completely objective entity, and exists in his own right, untainted by the psychology of the medium. Here we encounter those cases where people are preoccupied with figures whom they keep secret, only to suddenly—and inexplicably—commit suicide.

At the fifth stage, the reality of being one’s self ceases to exist; it is the stage of absolute reality, of absolute ecstasy. One has changed into something completely different, and the person becomes completely absorbed into a certain absolute existence. This stepping out of reality is precisely what the mystics describe.

328. See note 162.

329. A concept Jung had introduced in 1916 (1957 [1916], §§ 166 sqq.), denoting “the collaboration of conscious and unconscious data” (ibid., § 167), later termed “active imagination” (e.g., 1968 [1935], §§ 390 sqq.). It describes the emergence of a “sequence of fantasies produced by deliberate concentration” (1936/1937, § 101). This method emerged out of his self-experimentation, in which “he deliberately gave free rein to his fantasy thinking and carefully noted what ensued” (Shamdasani, in Swann, 2011, p. xi), entering into a dialogue with the visionary figures he encountered.

330. Planet Mars, pp. 22, 41 sqq., 57, 83. On the figure of Léopold in general, see ibid., chapter 4, “The Personality of Léopold,” pp. 51–86.

331. Ibid., pp. 60–61.

332. Dumas, 1846–1848 [1860]; the scene with the carafe of water in chapter 15. Dumas was inspired to write this novel by the life and personality of the Count Alessandro di Cagliostro (1743–1795), an alias for the occultist and adventurer Giuseppe (or Joseph) Balsamo.

333. Marie Antoinette, born Maria Antonia (1755–1793), daughter of the Austrian Empress Maria Theresia, archduchess of Austria, later dauphine of France (1770–1774), and, as wife of Louis XVI, queen of France and of Navarre. In the French Revolution, she and her husband were executed by guillotine in 1793.

334. Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772), Swedish scientist, philosopher, revelator, and mystic; best known for his book on the afterlife, Heaven and Hell (1758). There are repeated references to Swedenborg in Jung’s works, e.g., to his vision of a fire in Stockholm, which allegedly proved to correspond to the facts (Jung, 1905b, §§ 706–707; 1952, § 902). Swedenborg’s experiences instigated Kant to anonymously write his Dreams of a Spirit-Seer (1766), quoted by Jung earlier (see p. 42).

335. Cf. Dumas, 1860 [1846–1848], chapters 2 and 3, particularly pp. 15, 18, 31.

336. Johann Adam Weishaupt (1748–1830), German philosopher and jurist. The society of the Illuminati was banned by the government of Bavaria in 1784; Weishaupt lost his position at the University of Ingolstadt and fled Bavaria.

337. Adolph Freiherr Knigge (1752–1796), German writer and Freemason. In 1780, Knigge joined the Bavarian Illuminati, but withdrew in 1784, due to dissensions with Weishaupt. His book (1788)—actually a treatise on the fundamental principles of human relations—enjoyed immense success, and in German the word “Knigge” still stands for “good manners” or (books on) etiquette.

338. Johann Gottfried (after 1802: von) Herder (1744–1803), important German philosopher, theologian, poet, and literary critic. He met the young Goethe in 1770, and inspired him to develop his own style. Later, Goethe secured him a position in Weimar as General Superintendent.

339. While at first “he immediately accepted . . . the hypothesis of M. Cuendet” (Planet Mars, p. 291) about the significance of LPD, he seemed to have forgotten this explanation when he was questioned again later, and explained “that he took as a pseudonym the first name of one of his friends from the last century, who was very dear to him, and who was part of the house of Austria though he didn’t play any historical role” (ibid.).

340. Ibid., p. 100.

341. “This austere and rigorous mentor . . . represents, in fact, a very common psychological attribute; there is no noble feminine soul that would not carry such a mentor in one of its recesses” (Planet Mars, p. 82; trans. modified).

342. Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928), British political activist and leader of the British suffragette movement. Although widely criticized for her militant methods (smashing windows, assaulting police officers, arson, etc.), her work is recognized as a crucial element in achieving women’s suffrage in Britain.

343. “Shadow consciousness” [Schattenbewusstsein] is not a technical term, and does not appear in Jung’s other writings. The concept of the “shadow” as such, however, of course plays a prominent role in his theory. He later defined the shadow as the “‘negative’ part of the personality, i.e., the sum of the hidden and unfavorable qualities, of the insufficiently developed functions, and the contents of the personal unconscious” (Jung, 1917–1942, § 1035; note added in 1942; trans. mod.).

344. Roughly, a feeling of uncertainty or incompleteness—an expression coined by Pierre Janet, to which Jung repeatedly referred, both in his works and his letters. With it, Janet described, in the case of psychasthenic patients, le fait essentiel dont tous les sujets se plaignent, le caractère inachevé, insuffisant, incomplet qu’ils attribuent à tous leurs phénomènes psychologiques [the essential fact of which all subjects complain, the unachieved, insufficient, incomplete character they attribute to all their psychological phenomena] (Janet, 1903, I, p. 264). See also note 177 [on Janet].