Lecture 6

24 NOVEMBER 1933

SUBMITTED QUESTIONS

I have received a letter from a lady who writes: 197

When you discussed the dream of the Seeress of Prevorst, you said: “As soon as we take sides with a dream, it assumes a fateful meaning.” You added that you could not treat a patient who believed in his [sic] dream. Now I ask myself: Would it not be somehow possible that this patient could be induced by the treatment itself to renounce his belief in the dream? Would not the fact alone that he consults the doctor be an indication that he is actually ready to change his attitude, and that he harbors a faint hope somebody could help him to abandon this belief?

I am utterly convinced that the Seeress would consult a doctor at best because of some secondary symptoms. Her fate illustrates that she no longer desired to live. On the contrary, she converted the doctor to turn towards the darkness with her. I have known such cases myself. Fate proves to be stronger.

The second questions regards cryptomnesia, that is, the revival of memories that we do not recognize as such, and the example for this in Nietzsche. 198 [Jung reads the relevant passage from Nietzsche’s Zarathustra as quoted in his dissertation:] 199

Now about the time that Zarathustra sojourned on the Happy Isles, it happened that a ship anchored at the isle on which standeth the smoking mountain, and the crew went ashore to shoot rabbits. About the noontide hour, however, when the captain and his men were together again, they saw suddenly a man coming towards them through the air, and a voice said distinctly: “It is time! It is the highest time!” But when the figure was nearest to them (it flew past quickly, however, like a shadow, in the direction of the volcano), then did they recognise with the greatest surprise that it was Zarathustra; for they had all seem him before except the captain himself . . . “Behold!” said the old helmsman, “there goeth Zarathustra to hell!”

Now, when Zarathustra goes to hell, it is completely irrelevant that the crew has gone ashore to shoot rabbits. Rabbits, of all things! Then I remembered, from my student days, a green book with a red edge from the Basel University library. So I looked for Justinus Kerner’s four-volume Blätter aus Prevorst, and found the pertaining story in it: “An extract of awe-inspiring import from the log of the ship Sphinx, in the year 1686, in the Mediterranean” [Ein Schrecken erweckender Auszug aus dem Journal des Schiffes Sphinx vom Jahre 1686 im mittelländischen Meere]: 200

The four captains and a merchant, Mr. Bell, went ashore on the island of Mt. Stromboli to shoot rabbits. At three o’clock they called the crew together to go aboard when they saw, to their inexpressible astonishment, two men flying rapidly over them through the air. One was dressed in black, the other in grey. They approached them very closely, in the greatest haste; to their greatest dismay they descended amid the burning flames into the crater of the terrible volcano, Mt. Stromboli.

The two men were acquaintances from London, and when Bell and the naval officers returned home, they heard that both men had died at about that time. I subsequently wrote to Nietzsche’s sister. In her reply, she mentioned that when Nietzsche was eleven years old, they visited their grandfather, Pastor Oehler, in Pobles, 201 whose old library held a complete set of Justinus Kerner’s writings. They furtively entered the library and illicitly read all the frightful stories contained in the Blätter aus Prevorst. 202 I read the Blätter myself in 1898; the Nietzsche edition of 1901 had yet to appear, and, that aside, it was not advisable to read Nietzsche in Basel in those days. How exactly this cryptomnesia occurred escapes me. Whenever any classical idea occurs to us, however, it will enter into association with all sorts of mnemonic material, either consciously or half-consciously.

***

In the last lecture, we observed that the “Seeress of Prevorst” identified with the dead priest; [in the dream] she lay down beside him on the bed, as if they were husband and wife, or for that matter as if she were already buried next to him. This suggests that she is more inclined to adjust not to outer events and happenings, but to what arises from within, that is, from the subject. It is dead certain that ghosts and similar phenomena are things that we experience within, as if they did not appear within the field of vision in front of us, but from behind, as it were, from the unconscious. The only guarantee we have that such things do exist is the [evidence of the] I. People are confronted with them through the I, as if something existed behind the I whose source we are completely ignorant of.

Clairvoyance more or less bears out this point: as if those people were able to see around the corner; or they hear things other people don’t. Something somehow reveals itself from within—or from “behind”; it does not come from the frontside, not from the clear world of consciousness, and it is not perceived by the sensory organs. This, however, occurs solely in a particular state. The Seeress, too, notices these things only when she is in an exceptional state.

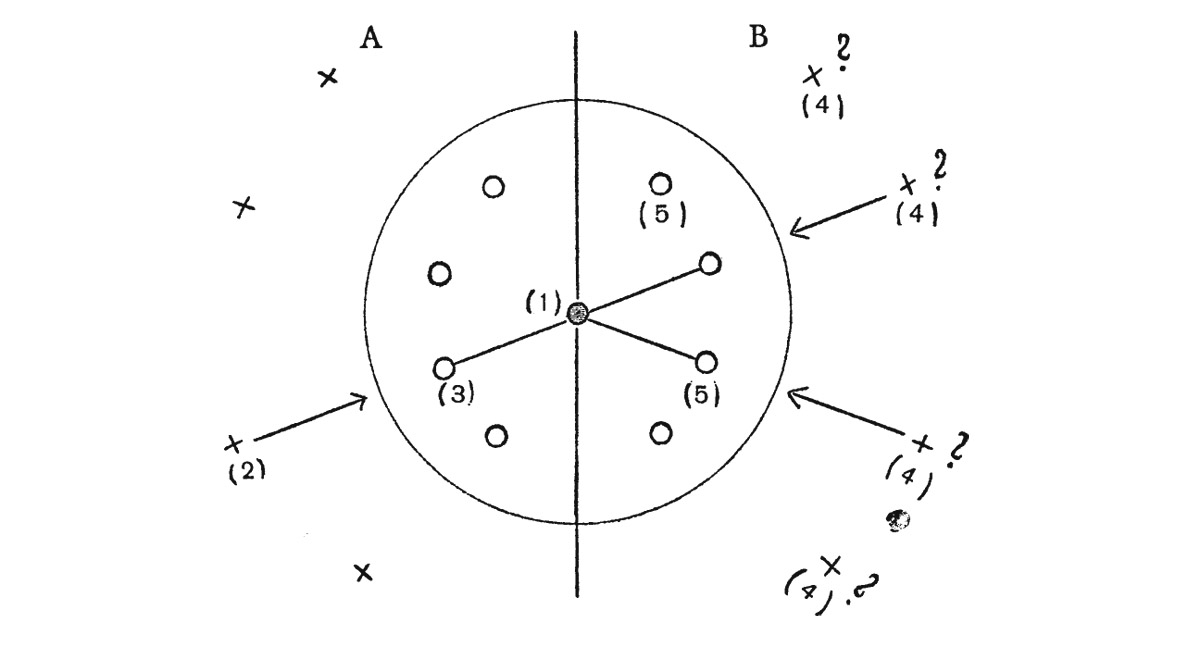

Thus, there are contents that come to us from the outside, and those that come from the inside, as the following diagram illustrates.

Our consciousness in the center is like a spider in its web, with threads, through which the psychic contents are associated with the I. This inner realm of consciousness is surrounded by outer objects that create an image in consciousness through the sense organs and the nerve tracts. We are dealing here with the objective facts of everyday life, with persons or things in the external world that make an impression on us. A Mr. X., for instance, makes an impact on consciousness and creates a psychic content.

Other impressions reach us from the invisible inner world. We can hypothesize that this background also contains objects, comparable to those in the external world, and that these objects equally leave an imprint in our consciousness, through images that are registered by our psyche. These psychic images are not necessarily conscious, just as many images constellated by outer objects do not reach our consciousness either—they are psychic contents, pure and simple. They are conscious only if they are associated with the I, otherwise they do not exist in consciousness. They can nevertheless act upon me, without my knowing, in this case, what is acting upon me. Thus, the I is in the center and acts like a magnet that attracts all contents.

This “I”—what a peculiar matter it is! First of all, it is something subjective. Nothing seems to be behind it, and yet you are able to think about the “I.” We can objectify it and make it the subject matter of our thinking. In speaking to you, I am aware of the fact that I am speaking to you. I can then tell myself: “You did that well,” or the opposite. It is as if someone else were standing behind me who observes me; a second I that comments upon the first I’s actions. Or it is as if you were in a labyrinth, with mirrors both behind and before you, so that your image is infinitely mirrored, and becomes ever smaller. For instance: I No. 1 is lecturing. I No. 2 hears that I No. 1 is lecturing. I No. 3 hears that I No. 2 hears that I No. 1 is lecturing. This hypothesis can be carried out ad infinitum, although we better not do this. The fact of this second I making its comments, however, is familiar to us all. It is what the English call “self-consciousness,” 203 that is, being conscious of oneself to a high degree. There is someone sitting behind you who can’t keep his trap shut, talking about you all the time. When this self-consciousness grows too strong, as in the case of stage fright, for instance, you become inhibited, and a pathological state can arise so that you have to undergo treatment.

Now there is indeed something behind it, and I have referred to this darkness as the subjective factor or the background, the subjective I. In the case of Mrs. Hauffe, for instance, we realize that there are matters “back there” that appear from within and are perceived by the “inner eye.” It is not a capability unique to the Seeress, however, to perceive these contents; we, too, are capable of it. Not during daytime, of course, but when you go to bed the most incredible ideas can occur to you. For instance, the idea of burglars enters your mind, and you hear them outside the window, or believe that you see them in the room. These thoughts come from within and are “real.” Not with all the will in the world can you get rid of them, although you know exactly that they are imagined: “Doctor, I believe that I have cancer. I obviously know that this is nonsense, but I cannot help myself. The more I resist it, the stronger the idea.” 204

We merely see the contents—that is, strange “realities,” obsessive thoughts for example, such as an imagined illness or the like; all we see are the contents, but we have no idea from where they come. It is possible that there are objects “back there” that enter consciousness, but this is merely a hypothesis that cannot be proven, because only the I can bear witness to it. While I can demonstrate that the psychic images in the foreground correspond to a real content, I cannot do likewise for those “at the back.”

It can happen to me that all of a sudden the idea of a burning house occurs to me, and nothing will make the thought go away. And word could reach me at that very moment that it is my house that is ablaze. So I think: Aha! Now I have the proof, the verification, of the fact that I have “second sight”—even though it was not my own house that I saw, but merely a house; however, it corresponds to my house that is ablaze. I have perceived real events in an unreal manner. And yet I am the sole proof, for no one else has seen the event.

There are a great number of cases, however, in which this “vision” corresponds to nothing in reality. In these cases a subjective factor is at play, a dark point that lies behind us. For instance, a pleasant, reasonable fellow awakes one morning, and suddenly a bad mood overcomes him. Naturally, he is oblivious of the subjective factor, but blames his wife or a badly cooked breakfast—and before long a row erupts between the couple. “Well, how did you know that your wife would annoy you?” “Well, I already knew that beforehand!” Something walked in and seized him from behind, and he projected it from the subjective background onto his wife. People always see these things in the outside world, even when they occur within themselves, and we project every day with the most unbelievable shamelessness. This mechanism is particularly apparent in newspapers, where the thoughts and moods of writers and politicians are projected into others de l’autre côté de la rivière; 205 that is where we like to see the devil.

After this somewhat ungainly attempt to elucidate matters at the limits of human cognition, let me return to the “Seeress of Prevorst.” In accord with her dream, the Seeress evidently expects to recover her health from what lies entirely in the background: she dreamt that she would regain her health if she lay down beside the dead priest. Thus, she expects her health to lie in this back-world, in the dark sphere. As I have already mentioned, this dream is very ominous; it is so ominous in fact that as a medical doctor I would doubt whether anything could be done. There are indeed cases where one is well-advised not to help. It is not worth it. Obviously, we must do our duty as doctors. But if you manage to heal someone at the expense of your own health, you have fallen victim to a misunderstanding. For the fact remains that there are people who are not supposed to become healthy, since they are not destined for life.

As you will recall, on the day after the dream, the Seeress was stricken by a fever that lasted a fortnight. No one knew what it was. The fever was followed by a neurotic state, what the French call a grande hystérie, which resulted in her death, seven years later, in 1829. On 13 February 1822, she had the dream; on 27 February 1822, what were believed to be “severe spasms in the breast” caused her to awaken from her sleep. 206 Probably, this was a nervous heart affection, in effect a “heart cramp.” Such cramps can have organic or psychic causes; the latter was certainly true in her case. This is a metaphor, that is, an instance of mimic representation. The body illustrates something that cannot reach consciousness. “My heart cramped up,” we say, or “my heart stood still”; it was “as if an iron fist had squashed my heart.” Such “heart metaphors” abound in the novels of the writer Adalbert Stifter. 207 The Seeress has received an ominous impression from “behind.” Naturally, she projects this condition outward: The nurse had left the water standing recklessly on the washstand, instead of placing it on her bedside table. In reality, it was rather the unconscious knowledge that her death was imminent that cramped her heart.

197. Jung probably did not read the full text of the letter, which is reproduced here in my English translation of the original held in the ETH Archives.

199. Jung had already used this as an example of cryptomnesia in his dissertation (1902, §§ 140–142), and also in his article on cryptomnesia (1905a, §§ 180–183). He further quoted it in his seminar on Nietzsche’s Zarathustra (1988, vol. 2, pp. 1215–1218), the seminar on Children’s Dreams (1987 [2008], p. 17), and in his contribution to Man and His Symbols (1964 [1961], §§ 455–456). The passage referred to is from Nietzsche, 1883–1885 [1911], p. 88. The emphasis was added, presumably by Jung himself (or the note-taker), to emphasize the concordances of the two texts.

200. Kerner, 1831–1839, vol. 4, p. 57.

201. MS: “Pobler,” because Jung misread the name of the village in Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche’s answer to his query.

202. Jung gave different versions of Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche’s information. While in 1902 and 1905, he correctly quoted her that Nietzsche had been between twelve and fifteen years old when he had read Kerner (1902, § 141; 1905a, § 182), in later accounts he repeated the version as given above, namely, that this happened sometime between his tenth and eleventh year (1964 [1961], § 456; 1987 [2008], p. 17; 1988 [1934–1939], p. 1218). He also somewhat embellished the story by adding that the children’s reading was done illicitly. This is not mentioned by Elisabeth Förster, and Nietzsche himself wrote: “My favourite place was granddad’s study, and it was my greatest pleasure to browse in the old books and journals” (in Janz, 1978, p. 62; my trans.)—which does not indicate any forbidden activity. On Jung’s correspondence with Nietzsche’s sister concerning this question see Bishop, 1997.

203. This word in English in the German transcripts.

204. Jung refers here to the case of “a professor of philosophy and psychology who consulted [him] about his cancer phobia. He suffered from a compulsive conviction that he had a malignant tumor, although nothing of the sort was ever found in dozens of X-ray pictures” (1964 [1961], § 467). Jung mentioned the case repeatedly, e.g., also in 1938 [1954], § 190, in his Terry Lectures (1939 [1937], §§ 12–13, 19–21, 26–27, 35–36), and in his seminar on Dream Interpretation Ancient & Modern (2014, p. 71).

205. French, from the other side of the river.

206. Seeress, p. 40.

207. Adalbert Stifter (1805–1868), Austrian writer, painter, and pedagogue.