Chen Yingwen, who writes under the name Chen Li (Ch’en Li), was born and raised in Hualian, on the east coast of Taiwan. He graduated from the English Department of National Taiwan Normal University in 1976 and has since been a middle school teacher. In recent years he has also taught creative writing at National Dong Hwa University in his hometown.

Chen started writing poetry in the 1970s, under the influence of modernism. He turned to social and political themes in the 1980s, and in the 1990s has explored a wide range of subjects and styles, combining formal and linguistic experiments with concern for indigenous cultures and the formation of a new Taiwanese identity.

To date Chen has published seven books of poetry. He is also a prolific prose writer and translator. In collaboration with his wife, literary critic Zhang Fenling (Chang Fen-ling), he has translated the work of a large number of Latin American and East European poets into Chinese, including Neruda and Szymborska. In 1999 he was invited to Rotterdam Poetry International.

THE LOVER OF THE MAGICIAN’S WIFE

How can I explain to you this breakfast scenery?

Orange juice falls off the fruit tree, and then flows along the river into cups;

sandwiches are conjured out of two beautiful roosters.

The sun always rises from the other end of the eggshell, in spite of the strong smell of the moon.

The table and chairs are just hacked off from the nearby forest;

you can even hear the leaves crying.

Maybe walnuts are hiding under the carpet, who knows?

Only the bed is stable.

But she’s so fond of Bach’s fugues—the magician’s wife whose fickleness is due to

people’s incredulity. You can’t but stay up the whole night fleeing with her.

(I’m most likely the one who pants after her, dog-tired …)

I’m afraid after she wakes up she’ll play the organ, drink coffee, and do her calisthenics.

Alas, who knows whether the coffee is boiling in the hat?

It’s my turn, perhaps, to be the next garrulous and verse-parading parrot.

(1976)

(translated by Zhang Fenling with Chen Li)

THE LOVE SONG OF BUFFET THE CLOWN

Simply because half the world’s sorrow is resting on his nose,

Buffet the Clown stays awake the whole night. He laughs,

radiating light as dutifully as a street lamp.

No other machine is more awkward; he hangs a hammer on his breast to guard, to watch over time,

as if his hands rather than his legs were the clock hands of infantile paralysis.

Our righteous Buffet knows no hunger.

He lives frugally, keeping his figure slim for the numerous affectionate ladies on the balcony.

His hat is a weathercock whose paint is chipped,

chasing the dandruff of dreams day and night.

His eyelashes are the illegitimate children of pelicans.

His sighs are the female cousins of crows.

But how proud the neck covered with lipstick marks,

persisting in its slenderness more gracefully than a giraffe.

Simply because half the world’s happiness is resting on his nose,

Buffet the Clown stays awake the whole night.

He laughs, he laughs, behind the eyes as sour and yellow as lemons.

For the tiny eyedrops of love

he must cry, must pretend to cry sadly.

No more honest magic can ever be seen.

He presses a curved glass wand close to his ears

to turn the evil curse into grape juice and make it flow into his mouth.

But you must forgive him for his speeding heartbeat;

timid Buffet is at best half a great rope-walker,

dancing shakily before the slanting electric guitars.

Ha, when the ladies and stars are frustrated in love,

Buffet the Clown reads the moonlight

and imitates a broken clockwork orange, singing silently.

Simply because half the world’s superiority is resting on his nose,

Buffet the Clown stays awake the whole night.

He cries, he laughs, in the upside-down dressing mirror.

For the sake of the ladies’ bright spirits

he adorns himself carefully, rubs laboriously

and polishes his wits as if they were worn-out shoes.

And without his knowledge dust moves into his hair,

wrinkles of desire crawl up his baby face like a giant spider …

Ha, Buffet the Clown has no mask.

Buffet the Clown has no Oedipus complex.

He must get angry, must get jealous,

must write his love poems on every disposable advertisement like a forgotten hero,

and on the great morning—

march into the printing house of sunshine with all the vermiform appendixes in the city.

(1978)

(translated by Zhang Fenling with Chen Li)

IN A CITY ALARMED BY A SERIES OF EARTHQUAKES

In a city alarmed by a series of earthquakes, I heard

a thousand black-hearted jackals say to their children,

“Mother, I was wrong.”

I heard the judge cry

and the priest repent. I heard

handcuffs fly out of newspapers, blackboards drop into a manure pit. I heard

literary men put down their hoes, farmers take off their glasses,

and fat businessmen take off their clothes of cream and balsam one by one.

In a city alarmed by a series of earthquakes,

I saw pimps on their knees returning vaginas to their daughters.

(1978)

(translated by Zhang Fenling with Chen Li)

LISTENING TO WINTERREISE ON A SPRING NIGHT—FOR FISCHER-DIESKAU

The world is getting old,

laden with such heavy love and nihilism.

The lion in your songs is getting old too,

still leaning affectionately against the childhood linden tree,

unwilling to give in to sleep.

Sleep may be desirable, when

the past days are like layers of snow

covering human misery and suffering.

It may be as well to have flowers in one’s dream,

when the lonely heart is still seeking green grass in the wilderness.

Spring flowers bloom on winter nights,

boiling tears freeze at the bottom of the lake.

The world teaches us to hope, and disappoints us too.

Our lives are the only thin sheet of paper we have,

covered with frost and dust, sighs and shadows.

We dream on the fragile paper—

none the lighter for all its shortness and thinness.

We grow trees in the dream that has been erased time and again,

and return to them

each time we feel sad.

I am listening to Winterreise on a spring night.

Your hoarse voice is the dream in my dream,

traveling along with winter and spring.

Author’s note: In January 1988, I heard Fischer-Dieskau, the famous German baritone, singing Schubert’s song cycle, Die Winterreise (Winter Journey) on satellite TV. Ever since I was a teenager, I have listened to Fischer-Dieskau’s recordings of numerous German songs, and I have never got tired of Winterreise. On this occasion, on a quiet midnight, I saw the performance of so many familiar songs, such as “Der Lindenbaum” (“The Linden Tree”) and “Frühlingstraum” (“Dream of Spring”), coming out of the throat of the sixty-three-year-old singer, along with the voice of time. I was moved to tears. How much love for art lies in Fischer-Dieskau’s aging voice, which reminds one of a life full of vicissitudes!

(1988)

(translated by Zhang Fenling with Chen Li)

Every day, from our teacups

flows a river of shadows.

The places spotted with lipstick marks

are the constantly vanishing

riverbanks.

A houseful of tea fragrance allures us into sleep.

What we drink may be time,

may be ourselves,

may be our parents, who have fallen into the cups.

We catch from the silty bottoms of the cups

last year’s scenery:

a mountainful of jasmine,

flowers blooming and falling.

We watch the cold river boiling once again,

warmly dissolving the descending darkness.

Then we sit drinking tea from the cups that

brighten up like lanterns. We sit

on the bank as high as a dream,

waiting for the tea to turn into the river,

for the trees to blossom and bear fruit,

till we, like our parents, are incarnated

in a fruit,

a camellia,

vanishing into the river of shadows.

(1992)

(translated by Zhang Fenling with Chen Li)

On the world map on a scale of one to forty million,

our island is an imperfect yellow button

lying loose on a blue uniform.

My existence is now a transparent thread,

thinner than a cobweb, going through my window facing the sea

and painstakingly sewing the island and the ocean together.

On the edge of the lonely days, in the crevice

between the new and the old years,

the thought is like a book of mirrors, coldly freezing

the ripples of time.

Thumbing through it, you’ll see pages of obscure

past, flashing brightly on the mirrors:

another secret button—

like an invisible tape recorder, pressed close to your breast,

repeatedly recording and playing

your memories and all mankind’s—

a secret tape mixed with love and hate,

dream and reality, suffering and joy.

What you hear now is

the sound of the world:

the heartbeats of the dead and the living

and your own. If you cry out with all your heart,

the dead and the living will speak to you

in clear voices.

On the edge of the island, on the boundary

between sleeping and waking,

my hand is holding my needle-like existence:

threading through the yellow button rounded and polished by

the people on the island, it pierces hard into

the heart of the earth lying beneath the blue uniform.

(1993)

(translated by Zhang Fenling with Chen Li)

1 A great event on the desolate

winter day: ear wax

drops on the desk.

2 A parade in honor of death:

strolling shoes working shoes sleeping

shoes dancing shoes …

3 On a night cold as iron:

the percussion music of two bodies

that strike against each other to make a fire.

4 All the sorrow of night will be turned into golden

ears of rice by daylight, waiting to be

reaped by another sorrowful night.

5 “Which runs faster, grass or dust?”

after a spring shower, beside a deserted railway,

someone asked me.

6 Having constantly broken world records,

our lonely shot-putter throws his head out

in one put.

7 The white skin turns a mole

into an island: I miss

the glistening vast ocean inside your clothes.

8 Sandals throughout the seasons: do you see

the free verse my two feet write, treading

upon the blackboard, upon the dust?

9 The story of marriage: a closet of loneliness plus

a closet of loneliness equals

a closet of loneliness.

10 A rondo now forte now piano:

the flush toilets of the nihilistic republic are playing

their mumbling national anthem again …

(1993)

(translated by Zhang Fenling with Chen Li)

When dear God uses sudden death

to test our loyalty to the world,

we are sitting on a swing woven of the tails of summer and autumn,

trying to swing over a tilting wall of experience

to borrow a brooch from the wind that blows in our faces.

But if all of a sudden our tightly clenched hands

should loosen in the dusk,

we have to hold on to the bodies of galloping plains,

speaking out loud to the boundless distance about our

colors, smells, shapes.

Like a tree signing its name with abstract existence,

we take off the clothes of leaves one after another,

take off the overweight joy, desire, thoughts,

and turn ourselves into a simple kite

to be pinned on the breast of our beloved:

a simple but pretty insect brooch,

flying in the dark dream,

climbing in the memory devoid of tears and whispers

till, once more, we find the light of love is

as light as the glow of loneliness, and the long day is but

the twin brother of the long night.

Therefore, we sit all the more willingly on a swing

interwoven of summer and autumn, and willingly mend

the tilting wall of emotion

when dear God uses sudden death

to test our loyalty to the world.

(1993)

(translated by Zhang Fenling with Chen Li)

(1995)

I’ve always thought that we are living on the cowhide

though God has granted my wish to mix my blood, urine,

and excrement with this land.

Exchange fifteen bolts of cloth for land as large as a cowhide?

The aborigines couldn’t possibly know that a cowhide could be cut

into strips and, like the spirit of omnipresent

God, encircle the whole Tayouan island,

the whole Formosa. I like the taste of

venison, I like cane sugar and bananas, I like

the raw silk shipped back to Holland by East India Company.

God’s spirit is like raw silk, smooth, holy, and pure.

It shines upon the youngsters from Bakloan and Tavacan

who come daily to the youth school to learn spelling, writing,

praying, and catechism. Oh Lord, I hear their Dutch

smell of venison (just like the Sideia language

I utter from time to time in my sermon).

Oh Lord, in Dalivo, I have taught fifteen married women and

maidens to say the Lord’s Prayer, the Gospel, the Ten Commandments,

and grace before and after meals; in Mattau, I have taught

seventy-two married and unmarried young men to say

various prayers, to know the main religious doctrines, to read,

and by sincerely teaching and preaching catechism, to start

enlarging their knowledge—oh, knowledge is like a cowhide

that can be folded and put into a traveling bag to carry

from Rotterdam to Batavia, from Batavia to

this subtropical island, and be unfolded into our Majesty’s agricultural land,

the Lord’s nation, cut into strips of twenty-five ges,

which length squared forms one morgen, and then three and four zhanglis.

In Zeelandia, between the public measurement office, the tax office,

and the theater, I see it flying like a flag, smiling remotely

at Provintia. Oh, knowledge

brings people joy, just like good food and myriad

spices (if only they knew how to cook Holland peas).

Oranges, with sour flesh and bitter skin, are larger than tangerines. But they don’t know that

in summer the water tastes even better than lovemaking when

mixed with salt and smashed oranges. In Tirosen,

I have acquainted thirty married young women with various prayers

and simplified key items; in Sinkan, one hundred and two

married men and women have been taught to read and write (oh, I

taste in the Bible in romanized aboriginal languages

a taste of venison flavored with European ginger).

Ecclesiastes in Favorlang, the Gospel according to Matthew in Sideia,

the marriage of the civilized and the primitive. Let God’s spirit

enter the flesh of Formosa—or, let the venison of Formosa enter my

stomach and spleen to become my blood, urine, and

excrement, to become my spirit. I’ve always thought that we are

living on the cowhide, although those Chinese troops are approaching

on junks and sampans with large axes and knives

attempting to cover us with an even bigger

cowhide. God has granted my wish to mix my blood,

urine, and excrement with the aborigines’

and print them, like letters, on this land.

How I wish they knew this cowhide, in which new spelling

words are wrapped, can be cut into strips and thumbed into

pages, a dictionary loaded with sounds, colors, images, smells

and as broad as God’s spirit.

Author’s note: Bakloan, Tavacan, Dalivo, Sinkan, Tirosen, and Mattau are names of communities of the plains aborigines in Taiwan. The Sideia language and the Favorlang language are dialects of the plains aborigines (Sideia is also called Siraya). Zeelandia was a city built on Tayouan island (now called Anping, in Tainan) by the colonists during the Dutch Occupation period (1624–1662). Provintia was a fort they built. It is said that the Dutch offered to exchange fifteen bolts of cloth with the aborigines for a cowhide-sized piece of land. After the agreement was made, they “cut the cowhide into strips and encircled land more than one kilometer in circumference” (see Lian Heng, A General History of Taiwan). “Ge” was a measuring unit used by the Dutch, equaling about twelve feet five inches. Twenty-five ges squared equals one morgen. Five morgens make one zhangli.

(1995)

(translated by Zhang Fenling with Chen Li)

—For Hikari Oe*

At the concert celebrating the sixtieth birthday of the conductor Seiji Ozawa, I hear the new duet by Hikari Oe, mentally retarded son of the novelist Kenzaburo Oe. The aging Russian cellist in exile, the gorgeous Argentine woman pianist. They are conversing. How do shadows weave a crown of laurel, how does imperfection contain the beauty of a flower? In life’s earth, stone, cloud, rain—lights, of language and music. Flying over the river of Time: “Wandering, drifting, what am I like?”** Exile, return, suspension, resolution. C string and chromosome, pain and love. On my video player whose right speaker is out of order so whenever it replays noises interfere incessantly, I hear so clearly a breeze blowing across fine grass on the riverbanks, my chest suddenly broadens as stars reach down. On my solitary transnational journey in the afternoon, I gladly pull out the passport issued by a fellow traveler from an earlier time:

“The moon rushing forward, the great river flows.”

(1996)

(translated by Michelle Yeh)

“The fluttering of ten thousand butterfly wings in the Southern Hemisphere causes a

typhoon in the summer mid-day dream of a woman near the Tropic of Cancer, who was chased by

love but betrayed love …” I found this sentence

in the meteorology book with color illustrations lying on the dressing table in your room.

Ah, the terrace of memory with metallic walls and glass floor,

where I once entered but later lost the key and could not

get in. With a navy blue eyebrow pencil you highlighted

in the book: “The staple food of the butterflies is love poems, especially

sad ones, ones that cannot be swallowed in one gulp and need to be chewed over and over …”

I mull over ways to reach you again: Dismember yesterday,

hang it up and let it float outside your building like a spider? Or, on the wings of

one butterfly stamp after another, deliver a parcel of longing and despair

to your door? Your smooth, tightly closed metallic walls make every single

crawling insect trying to climb up slip and fall off the building …

So I wait for the fluttering of butterfly wings in the Southern Hemisphere to cause a

typhoon in your summer mid-day dream, to allow the butterfly shadows secretly issued by sorrow

to flap and strike the doors and windows of your heart, and let a question mark,

a comma, in the incompletely digested poem stir up your memory

like a tiny screw, pop the top of the old perfume bottle sitting on your

nightstand, so that you can hear anew the chirping insects, barking dogs, singing clowns

without a nose that we once heard together and are stored inside,

so that you can smell anew the perspiration and scented mud that we once rolled on:

at the bottom of a deep lake a summer night’s conversation that cannot be stopped.

Now our hearts are as far apart as the two poles of the globe, although my eyes,

like a thumbtack, still fix on the longitude and latitude of where you are on the map.

I can only write a poem, a sad poem, to make the butterflies in the Southern Hemisphere fight for food

and make them flutter ten thousand wings so as to cause a typhoon

in the summer mid-day dream of you, behind metallic walls in a tall building near the Tropic of Cancer.

(1996)

(translated by Michelle Yeh)

From a distance your weeping

drills a tunnel in my body.

This morning I return to the familiar darkness,

enter the cell of honeycomb that belongs to me,

waiting for sorrow to drip like honey.

In amber-colored time I solidify,

feeding on imaginary death, on soft candy

of emptiness. Your weeping

is a soundless inscription on my ear;

at the end of the tunnel it sparkles into

a translucent rain tree.

Look for its shape, not for its entrance.

A tunnel passes through a life of grief connecting you and me.

(1997)

(translated by Michelle Yeh)

1 A hundred-pacer snake stole my necklace and singing voice.

I will go beyond the mountain to get them back.

But Mother, look!

He has torn my necklace up, cast it down to the valley,

and turned it into starlight flowing all night long.

He has compressed my singing voice into a teardrop,

falling on the silent feathered tail of a black long-tailed pheasant.

2 Our canoe has drifted from the ocean of myth to the beach tonight.

Our canoe, my brother, has landed anew, along with this line of words.

3 A fly has flown onto the sticky flypaper below the goddess’s navel.

Just as the day hammers gently on the night,

my dear ancestor, hammer gently with the unused Neolithic tool between your thighs.

4 We do not die, we just grow old,

we do not grow old, we just change plumage,

like the sea changing its bedsheets

in the stone cradle, at once ancient and young.

5 His fishing rod is a rainbow of seven colors,

bending slowly down from the sky

to hook every swimming dream.

Ah, his fishing rod is a bow of seven colors

that aims at every black-and-white fish flying out of the subconscious.

6 Because the bees buzz underground,

we have earthquakes. Yet earthquakes

can be sweet, if a bit of honey should

seep through the cracks of the

earth’s crust, through the cracks of the heart.

7 She stood singing on a rock with her brother on her back;

the god who heard the singing voice fetched her to heaven.

But she felt like eating millet, so she asked her father

for three grains to sow them in heaven.

“On hearing thunder, just picture me

threshing millet.”

At the sight of lightning, we’ll assume

she has threshed open her homesickness again.

8 Her body, unopened by desire,

is a cement room without doors and windows.

“Drill a hole through my wall, Mother.

Numerous fleas are anxious to rush out of the dark ages,

out of my soft, swelling hahabisi,

to receive the baptism of light.”

9 Under the giant Harleus’s crotch hid a rapid transit system.

His eight-kilometer-long penis is the most flexible viaduct,

crossing swiftly running dales, crossing mountain ranges,

stretching from Village Hikayiou to Village Pianan.

Fair girls, while you enjoy the ecstasy of free transportation, beware

that his fleshy bridge may suddenly turn its direction

and creep into your dark tunnels.

10 The day is too long, the night is too short,

and the valley of death too far away.

My dear sisters, leave the taro fields

to men, and sweat to ourselves.

Let’s put the hoes on our heads like horns

and become goats, to take shelter from the sun under trees.

You are a goat,

and I am a goat.

Away from men, away from toil,

we play and enjoy the cool breeze in the shade.

Author’s note: The black long-tailed pheasant is a rare bird found in the Taroko Gorge National Park. There is a legend about the origin of the Amis: a brother and sister sought shelter from a deluge and drifted to the east coast of Taiwan on a canoe. According to the Atayal myth of the creation, there were a god and a goddess in very ancient times who were ignorant of lovemaking until one day a fly landed on the private part of the goddess (the Amis have a similar myth). According to a Saisiyat legend, old people could recover their youth simply by peeling off the skin. An Ami myth has it that the rainbow was originally the seven-color bow of Adgus, the hunter who shot down the sun. There is an Ami legend about how earthquake was formed: the people living on the ground cheated those living underground by exchanging hemp bags filled with bees for goods. The Paiwan have stories about a girl singing on a rock with her little brother on her back and being delivered to heaven because she aroused the gods’ sympathy and affection. A Bunun legend goes like this: once upon a time there was a beautiful girl whose private part (hahabisi in the Bunun language) was a little swollen but tightly sealed. Her mother cut it open with a knife, and out sprang numerous fleas. There is an Atayal legend about the giant Harleus, who had a tremendously long penis. He stretched it out as a bridge for people to cross flooded rivers, but he got lustful at the sight of pretty girls. A Puyuma legend goes like this: two girls were close friends. One day they worked in the taro field on the mountain. It was so hot that they took shelter from the sun under a tree. Rejoicing, they put hoes on their heads and were turned into goats.

(1998)

(translated by Zhang Fenling with Chen Li)

I cultivate a space

with loneliness, with breath.

Two or three plastic bottles on the floor,

a laundered pair of orange panties

dripping from the stainless steel dripping.

I cultivate orange smell,

shampoo, wings of a glider.

I cultivate a word in lower case

veronica: cloth with the holy face of

Jesus; a bullfighting pose (with both feet

planted, the bullfighter slowly moves

the cloth away from the attacking bull).

I cultivate a closet in which hang a pair of black jeans

and a blue T-shirt.

I cultivate a laptop computer awaiting the input

of the sea and a range of waves.

I cultivate a gap:

isolating me from the world

and leading me to your human world hanging under the belly button.

I cultivate the tortuous, complex nation-building history

of a newest, smallest country.

(1998)

(translated by Michelle Yeh)

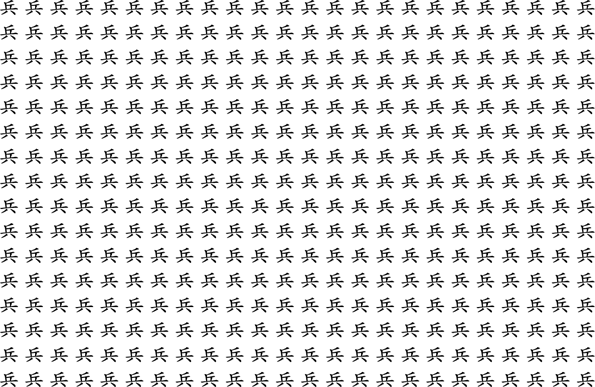

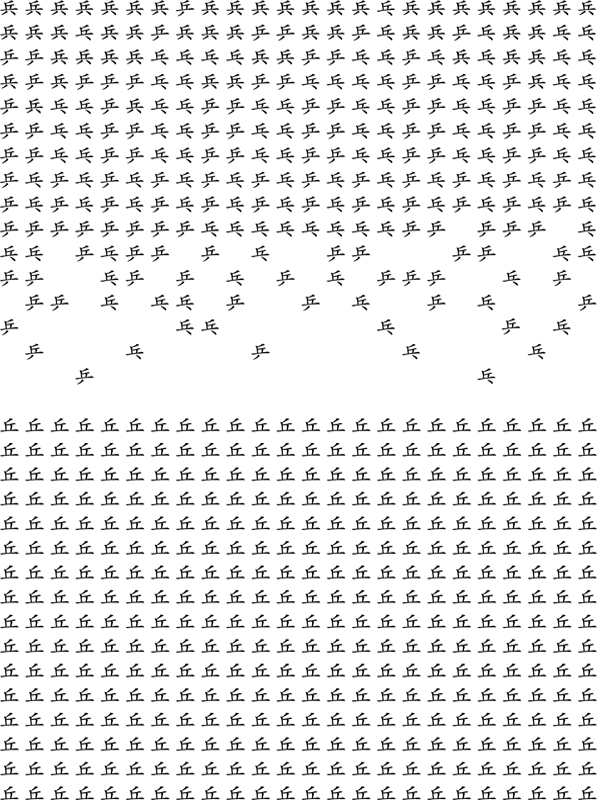

*The Chinese character  (pronounced “bing”) means “soldier.”

(pronounced “bing”) means “soldier.”  and

and  (pronounced “ping” and “pong”), which look like one-legged soldiers, are two onomatopoeic words imitating sounds of collision or gunshots. The character

(pronounced “ping” and “pong”), which look like one-legged soldiers, are two onomatopoeic words imitating sounds of collision or gunshots. The character  (pronounced “qiu”) means “hill” or “mound.”

(pronounced “qiu”) means “hill” or “mound.”

*Hikari Oe was born with a brain hernia in 1963 and did not speak his first word till the age of six. At thirty-two he started writing music; he has since become an internationally acclaimed composer. In his 1994 Nobel lecture, Kenzaburo Oe (b. 1935) described his own writing as a coming to terms with his son’s condition and referred to “the exquisite healing power of art.” “Hikari” literally means “light,” and “Oe” means “great river.”

**The question “Wandering, drifting, what am I like?” and the last line of the poem are direct quotes from “Thoughts on a Night Journey” by Du Fu (712–770).