M BLM NEWSPAPER ROCK HISTORICAL MONUMENT

M NEEDLES AND ANTICLINE OVERLOOKS

BIG SPRING CANYON SCENIC DRIVE

MOUNTAIN BIKING AND 4WD EXPLORATION

RIVER-RUNNING ABOVE THE CONFLUENCE

M RIVER-RUNNING THROUGH CATARACT CANYON

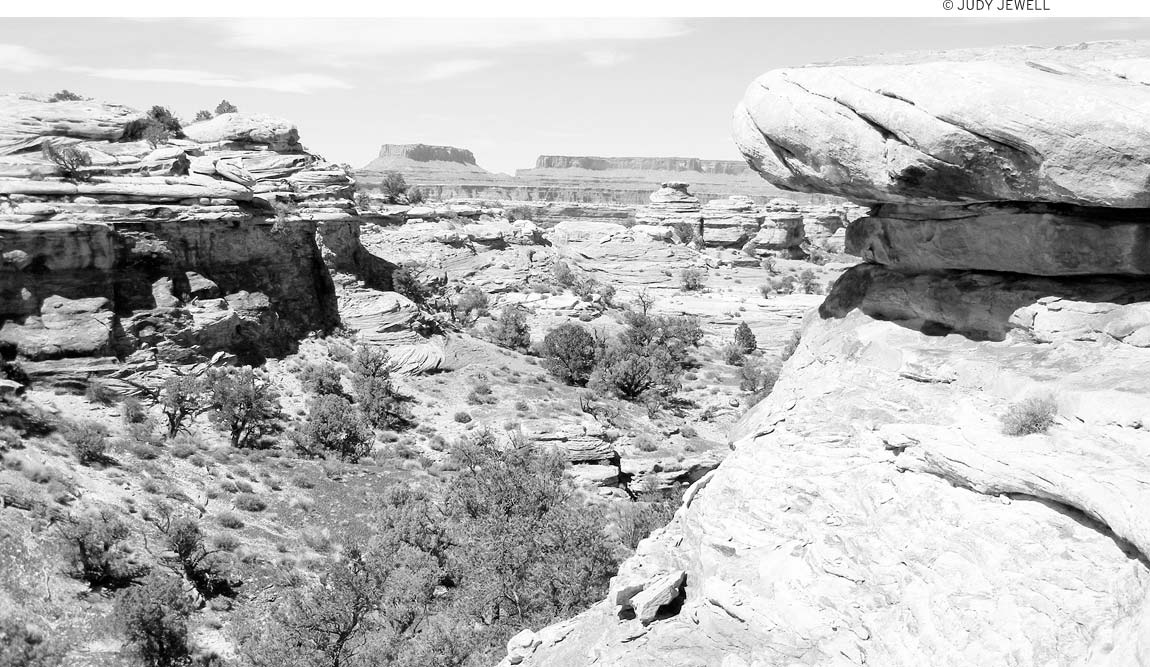

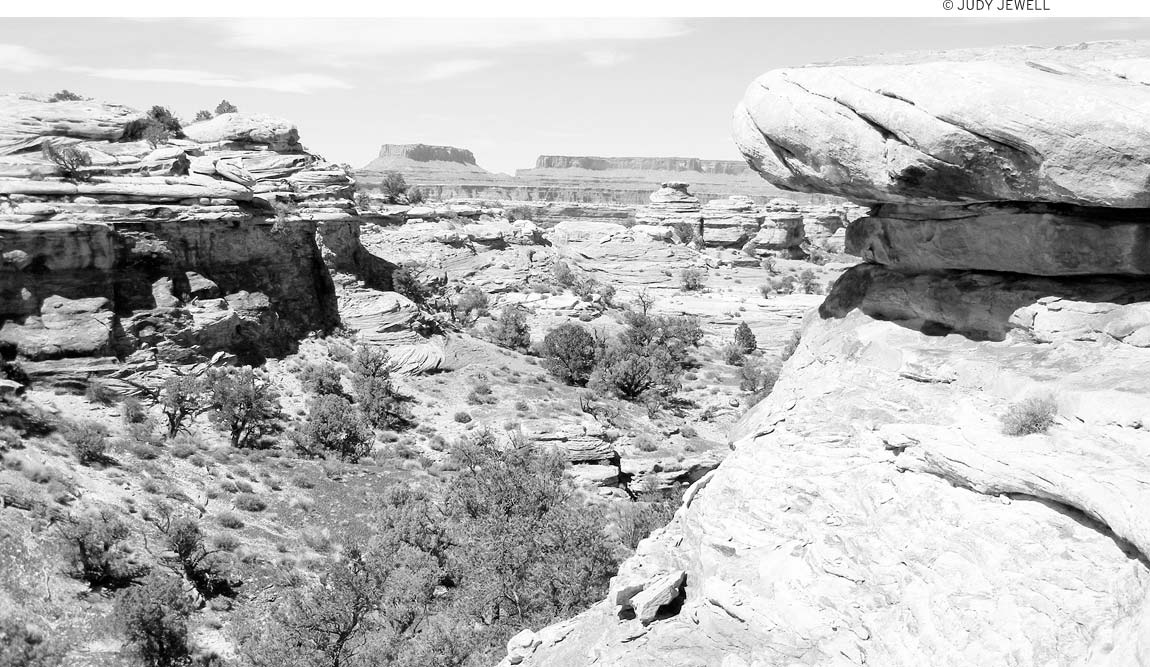

The canyon country of southeastern Utah puts on its supreme performance in this vast park, which spreads across 527 square miles. The deeply entrenched Colorado and Green Rivers meet in its heart, and then continue south, as the mighty Colorado, through tumultuous Cataract Canyon Rapids. The park is divided into four districts and a separate noncontiguous unit. The Colorado and Green Rivers form the River District and divide Canyonlands National Park into three other regions. Island in the Sky is north, between the rivers; the Maze is to the west; and Needles is to the east. The Horseshoe Canyon Unit is farther to the west. This small parcel of land preserves a canyon on Barrier Creek, a tributary of the Green River, in which astounding petroglyphs and other ancient rock paintings are protected.

Each district has its own distinct character. No bridges or roads directly connect the three land districts and the Horseshoe Canyon Unit, so most visitors have to leave the park to go from one region to another. The huge park can be seen in many ways and on many levels. Paved roads reach a few areas, 4WD roads go to more places, and hiking trails reach still more, but much of the land shows no trace of human passage. To get the big picture, you can fly over this incredible complex of canyons on an air tour; however, only a river trip or a hike lets you experience the solitude and detail of the land.

The park can be visited in any season of the year, with spring and autumn the best choices. Summer temperatures can climb over 100°F; carrying and drinking lots of water becomes critical then (bring at least one gallon per person per day). Arm yourself with insect repellent late spring-midsummer. Winter days tend to be bright and sunny, although nighttime temperatures can dip into the teens or even below zero Fahrenheit. Winter visitors should inquire about travel conditions, as snow and ice occasionally close roads and trails at higher elevations.

Unless you have a great deal of time, you can’t really “do” the entire park in one trip. It’s best to pick one section and concentrate on it.

The mesa-top Island in the Sky District has paved roads on its top to impressive belvederes such as Grand View Point and the strange Upheaval Dome. If you’re short on time or don’t want to make a rigorous backcountry trip, you’ll find this district the best choice. It is easily visited as a day trip from Moab. The “Island,” which is actually a large mesa, is much like nearby Dead Horse Point on a giant scale; a narrow neck of land connects the north side with the “mainland.”

If you’re really on a tight schedule, it’s possible to spend a few hours exploring Arches National Park, then head to Island in the Sky for a drive to the scenic Grand View overlook and a brief hike to Mesa Arch or the Upheaval Dome viewpoint. A one-day visit should include these elements, plus a hike along the Neck Spring Trail. For a longer visit, hikers, mountain bikers, and those with suitable high-clearance 4WD vehicles can drop off the Island in the Sky and descend about 1,300 feet to White Rim Road, which follows the cliffs of the White Rim around most of the island. Plan to spend at least 2-3 days exploring this 100-mile-long road.

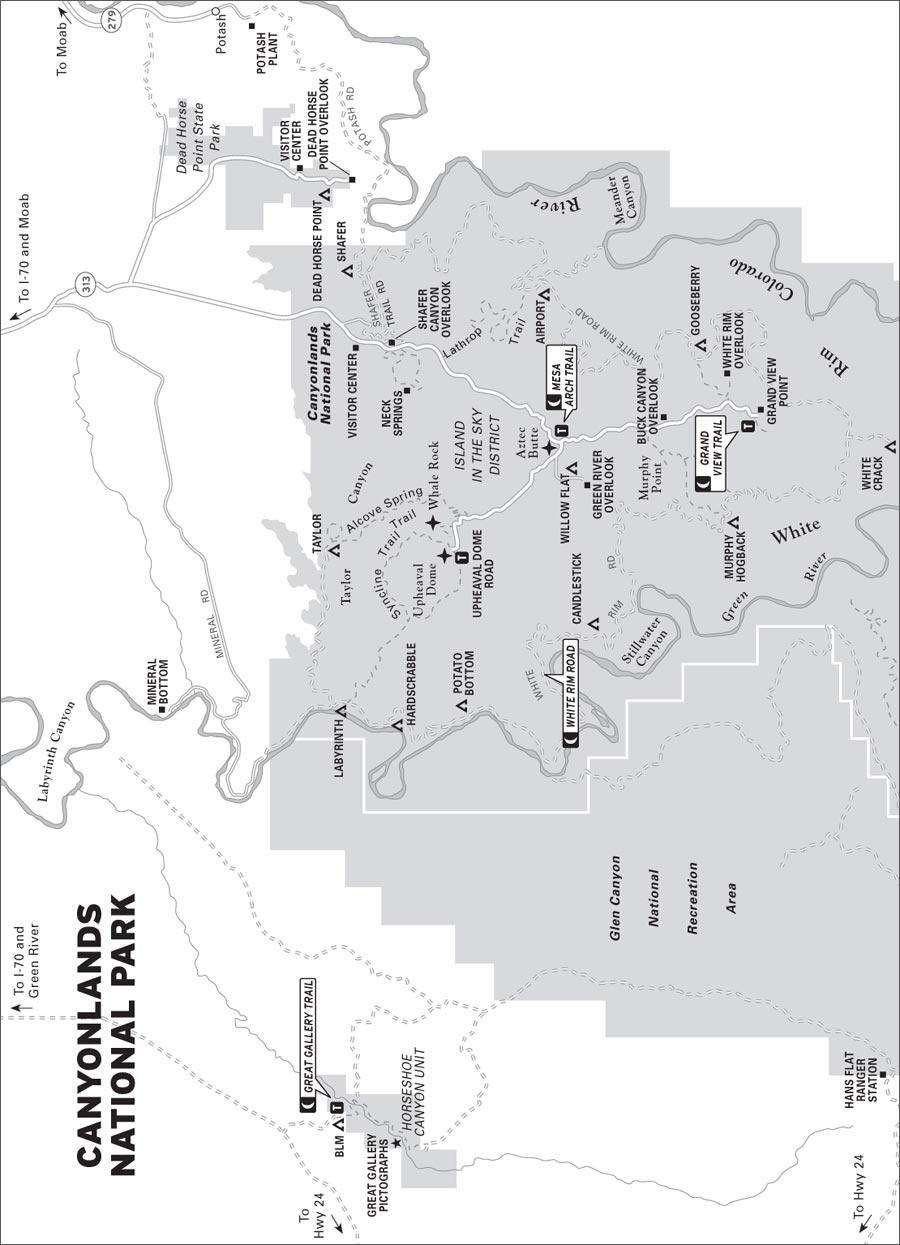

Colorful rock spires prompted the name of the Needles District, which is easily accessed from Highway 211 and U.S. 191 south of Moab. Splendid canyons contain many arches, strange rock formations, and archaeological sites. Overlooks and short nature trails can be enjoyed from the paved scenic drive in the park; if you are only here for a day, hike the Cave Spring and Pothole Point Trails. On a longer visit, make a loop of the Big Spring and Squaw Canyon Trails, and hike to Chesler Park. A 10-mile round-trip hike will take you to the Confluence Overlook, a great view of the junction of the Green and Colorado Rivers.

Drivers with 4WD vehicles have their own challenging roads through canyons and other highly scenic areas.

Few visitors make it over to the Maze District, which is some of the wildest country in the United States. Only the rivers and a handful of 4WD roads and hiking trails provide access. Experienced hikers can explore the maze of canyons on unmarked routes. Plan to spend at least 2-3 days in this area; even if you’re only taking day hikes, it can take a long time to get to any destination here. That said, a hike from the Maze Overlook to the Harvest Scene pictographs is a good bet if you don’t have a lot of time. If you have more than one day, head to the Land of Standing Rocks area and hike north to the Chocolate Drops.

Horseshoe Canyon Unit, a detached section of the park northwest of the Maze District, is equally remote. It protects the Great Gallery, a group of pictographs left by prehistoric Native Americans. This ancient artwork is reached at the end of a series of long unpaved roads and down a canyon on a moderately challenging hiking trail. Plan to spend a full day exploring this area.

The River District includes long stretches of the Green and the Colorado Rivers. River-running is one of the best ways to experience the inner depths of the park. Boaters can obtain helpful literature and advice from park rangers. Groups planning their own trip through Cataract Canyon need a river-running permit. Flat-water permits are also required. River outfitters based in Moab offer trips ranging from half a day to several days in length.

There are four districts and a noncontiguous unit in Canyonlands National Park (www.nps.gov/cany, $10 per vehicle, $5 bicyclists, motorcyclists, and pedestrians, good for one week in all districts, no fee to enter Maze or Horseshoe Canyon), each affording great views, spectacular geology, a chance to see wildlife, and endless opportunities to explore. You won’t find crowds or elaborate park facilities because most of Canyonlands remains a primitive backcountry park. If your plans include visiting Arches National Park plus Hovenweep and Natural Bridges National Monuments, consider the so-called Local Passport ($25), which allows entry to each of these federal preserves. Purchase the pass at any park or national monument entrance.

Front-country camping is allowed only in established campgrounds at Willow Flat (Island in the Sky) and Squaw Flat (Needles).

Rock climbing is allowed in the park, and permits are not required, unless the trip involves overnight camping; however, it’s always a good idea to check in at district visitors centers for advice and information and to learn where climbing is restricted. Climbing is not allowed within 300 feet of cultural sites.

Pets aren’t allowed on trails and must be leashed in campgrounds. No firewood collecting is permitted in the park; backpackers must use gas stoves for cooking. Vehicle and boat campers can bring in firewood but must use grills or fire pans.

The best maps for the park are a series of topographic maps by National Geographic/Trails Illustrated; these have the latest trail and road information. For most day hikes, the simple maps issued by park visitors centers will suffice.

Since Canyonlands covers so much far-flung territory, separate visitors centers serve each district. One website (www.nps.gov/cany) serves the whole park and is a good source for current information and permit applications. There are visitors centers at the entrances to the Island in the Sky District (435/259-4712, 9am-4pm daily winter, longer hours daily spring-fall) and the Needles District (435/259-4711, 9am-4pm daily mid-Feb.-early Dec., longer hours mid-Feb.-Nov.). The Hans Flat Ranger Station (435/259-2652, 8am-4:30pm daily year-round) is on a remote plateau above the even more isolated canyons of the Maze District and the Horseshoe Canyon Unit. The River District is administered out of the National Park Service Office (2282 SW Resource Blvd., Moab, 435/719-2313, 8am-4pm Mon.-Fri.). This office can generally handle inquiries for all districts of the park. For backcountry information, or to make backcountry reservations, call 435/259-4351. Handouts from the ranger offices describe natural history, travel, and other aspects of the park.

If you are in Moab, it is most convenient to stop at the Moab Information Center (Main St. and Center St., 435/259-8825 or 800/635-6622), where a national park ranger is often on duty. All visitors centers have brochures, maps, and books, as well as someone to answer your questions.

Rangers lead interpretive programs in the Island in the Sky and Needles Districts (Mar.-Oct.), and they guide hikers into Horseshoe Canyon (Sat.-Sun. spring and fall), weather permitting. Call the Hans Flat Ranger Station (435/259-2652) for details.

Outfitters must be authorized by the National Park Service to operate in Canyonlands. Most guides concentrate on river trips, but some can take you on mountain bike trips, including vehicle-supported tours of the White Rim 4WD Trail. Most of the guides operating in Canyonlands are based in Moab. For a complete list of authorized outfitters, visit the park website (www.nps.gov/cany).

• Escape Adventures (at Moab Cyclery, 391 S. Main St., Moab, 435/259-7423 or 800/596-2953, www.escapeadventures.com)

• Rim Tours (1233 S. U.S. 191, Moab, 435/259-5223 or 800/626-7335, www.rimtours.com)

• Western Spirit Cycling (478 Mill Creek Dr., Moab, 435/259-8732 or 800/845-2453, www.westernspirit.com)

• Adrift Adventures (378 N. Main St., Moab, 435/259-8594 or 800/874-4483, www.adrift.net)

• Navtec Expeditions (321 N. Main St., Moab, 435/259-7983 or 800/833-1278, www.navtec.com)

• Sheri Griffith Expeditions (503/259-8229 or 800/332-2439, www.griffithexp.com)

• Tag-A-Long Expeditions (452 N. Main St., Moab, 435/259-8946 or 800/453-3292, www.tagalong.com)

• Western River Expeditions (225 S. Main St., Moab, 435/259-7019 or 866/904-1163, www.westernriver.com)

A complex system of fees is charged for backcountry camping, 4WD exploration, and river rafting. Except for the main campgrounds at Willow Flat (Island in the Sky) and Squaw Flat (Needles), you’ll need a permit for backcountry camping. There is a $30 fee for a backpacking permit and, in the Needles District, a $10 day-use fee for a 4WD vehicle. Each of the three major districts has a different policy for backcountry vehicle camping, so it’s a good idea to make sure that you understand the details. Backcountry permits are also needed for any trips with horses or stock; check with a ranger for details.

It’s possible to reserve a backcountry permit in advance; for spring and fall travel to popular areas like Island in the Sky’s White Rim Trail or the Needles backcountry, this is an extremely good idea. Find application forms on the Canyonlands website (www.nps.gov/cany). Forms should be completed and returned at least two weeks in advance of your planned trip. Telephone reservations are not accepted.

Back-road travel is a popular method of exploring the park. Canyonlands National Park offers hundreds of miles of exceptionally scenic jeep roads, favorites both with mountain bikers and 4WD enthusiasts. Park regulations require all motorized vehicles to have proper registration and licensing for highway use, and all-terrain vehicles are prohibited in the park; drivers must also be licensed. Normally you must have a vehicle with both 4WD and high clearance. It’s essential for both motor vehicles and bicycles to stay on existing roads to prevent damage to the delicate desert vegetation. Carry tools, extra fuel, water, and food in case you break down in a remote area.

Before making a trip, drivers and cyclists should talk with a ranger to register and to check on current road conditions, which can change drastically from one day to the next. The rangers can also tell you where to seek help if you get stuck. Primitive campgrounds are provided on most of the roads, but you’ll need a backcountry permit from a ranger. Books on backcountry exploration include Charles Wells’s Guide to Moab, UT Backroads & 4-Wheel Drive Trails, which includes Canyonlands, and Damian Fagan and David Williams’s A Naturalist’s Guide to the White Rim Trail.

One more thing about backcountry travel in Canyonlands: You may need to pack your poop out of the backcountry. Because of the abundance of slickrock and the desert conditions, it’s not always possible to dig a hole, and you can’t just leave your waste on a rock until it decomposes (decomposition is a very slow process in these conditions). Check with the ranger when you pick up your backcountry permit for more information.

The main part of this district sits on a mesa high above the Colorado and Green Rivers. It is connected to points north by a narrow land bridge just wide enough for the road, known as “the neck,” which forms the only vehicle access to the 40-square-mile Island in the Sky. Panoramic views from the “Island” can be enjoyed from any point along the rim; you’ll see much of the park and southeastern Utah.

Short hiking trails lead to overlooks and to Mesa Arch, Aztec Butte, Whale Rock, Upheaval Dome, and other features. Longer trails make steep, strenuous descents from the Island to the White Rim Road below. Elevations on the Island average about 6,000 feet.

Although the massive cliffs in the area look to be perfect for rock climbing, in fact much of the rock is not suitable for climbing, and the remoteness of the area means that few routes have been explored. One exception is Taylor Canyon, in the extreme northwest corner of the park, which is reached by lengthy and rugged 4WD roads.

Bring water for all hiking, camping, and travel in Island in the Sky. Except for the bottled water sold at the visitors center, there is no water available in this district of the park.

Stop here for information about Island in the Sky and to see exhibits on geology and history; books and maps are available for purchase. The visitors center (435/259-4712, 9am-4pm daily winter, longer hours spring-fall) is located just before the neck crosses to Island in the Sky. From Moab, go northwest 10 miles on U.S. 191, then turn left and drive 15 miles on Highway 313 to the junction for Dead Horse Point State Park. From here, continue straight for seven miles. Many of the park’s plants grow and are identified outside the visitors center; look also at the display of pressed plants inside the center.

Half a mile past the visitors center is the Shafer Canyon Overlook (on the left, just before crossing the neck). The overlook has good views east down the canyon and onto the incredibly twisting Shafer Trail Road. Cattlemen Frank and John Schafer built the trail in the early 1900s to move stock to additional pastures (the c in their name was later dropped by mapmakers). Uranium prospectors upgraded the trail to a 4WD road during the 1950s so that they could reach their claims at the base of the cliffs. Today, Shafer Trail Road connects the mesa top with White Rim Road and Potash Road, four miles and 1,200 vertical feet below. High-clearance vehicles should be used on the Shafer. It’s also fun to ride this road on a mountain bike. Road conditions can vary considerably, so contact a ranger before starting. Shafer Trail Viewpoint, across the neck, provides another perspective 0.5 miles farther.

Back on top of the Island, the paved park road leads south from the neck six miles across Gray’s Pasture to a junction. The Grand View Point Overlook road continues south while the road to Upheaval Dome turns west.

As the park road continues south, a series of incredible vistas over the canyons of the Green and Colorado Rivers peek into view. The first viewpoint is Buck Canyon Overlook, which looks east over the Colorado River Canyon. Two miles farther is the Grand View Picnic Area, a handy lunch stop.

At the end of the main road, one mile past the Grand View Picnic Area, is Grand View Point, perhaps the most spectacular panorama from Island in the Sky. Monument Basin lies directly below, and countless canyons, the Colorado River, the Needles, and mountain ranges are in the distance. The easy 1.5-mile Grand View Trail continues past the end of the road for other vistas from the point.

Return to the main road to explore more overlooks and geological curiosities in the western portion of Island in the Sky.

The Green River Overlook is just west of the main junction on an unpaved road. From the overlook, Soda Springs Basin and a section of the Green River (deeply entrenched in Stillwater Canyon) can be seen below. Small Willow Flat Campground is on the way to the overlook.

At the end of the road, 5.3 miles northwest of the junction, is Upheaval Dome. This geologic oddity is a fantastically deformed pile of rock sprawled across a crater about three miles wide and 1,200 feet deep. For many years, Upheaval Dome has kept geologists busy trying to figure out its origins. They once assumed that salt of the Paradox Formation pushed the rock layers upward to form the dome. Now, however, strong evidence suggests that a meteorite impact created the structure. The surrounding ring depression, caused by collapse, and the convergence of rock layers upward toward the center correspond precisely to known impact structures. Shatter cones and microscopic analysis also indicate an impact origin. When the meteorite struck, sometime in the last 150 million years, it formed a crater up to five miles across. Erosion removed some of the overlying rock—perhaps as much as a vertical mile. The underlying salt may have played a role in uplifting the central section.

The easy Crater View Trail leads to overlooks on the rim of Upheaval Dome; the first viewpoint is 0.5 miles round-trip, and the second is one mile round-trip. There’s also a small picnic area here.

This driving adventure follows the White Rim below the sheer cliffs of Island in the Sky. A close look at the light-colored surface reveals ripple marks and cross beds laid down near an ancient coastline. The plateau’s east side is about 800 feet above the Colorado River. On the west side, the plateau meets the bank of the Green River.

Travel along the winding road presents a constantly changing panorama of rock, canyons, river, and sky. Keep an eye out for desert bighorn sheep. You’ll see all three levels of Island in the Sky District, from the high plateaus to the White Rim to the rivers.

Only 4WD vehicles with high clearance can make the trip. With the proper vehicle, driving is mostly easy but slow and winding; a few steep or rough sections have to be negotiated. The 100-mile trip takes 2-3 days. Allow an extra day to travel all the road spurs.

Mountain bikers find this a great trip too; most cyclists arrange an accompanying 4WD vehicle to carry water and camping gear. Primitive campgrounds along the way provide convenient stopping places. Both cyclists and 4WD drivers must obtain reservations and a backcountry permit ($30) for the White Rim campsites from the Island in the Sky visitors center. Find application forms on the Canyonlands website (www.nps.gov/cany); return the completed application at least two weeks in advance of your planned trip. Questions can be fielded via telephone (435/259-4351, 8am-12:30pm Mon.-Fri.), but no telephone reservations are accepted. Demand exceeds supply during the popular spring and autumn seasons, when you should make reservations as far in advance as possible. No services or developed water sources exist anywhere on the drive, so be sure to have plenty of fuel and water with some to spare. Access points are Shafer Trail Road (from near Island in the Sky) and Potash Road (Hwy. 279 from Moab) on the east and Mineral Bottom Road on the west. White Rim sandstone forms the distinctive plateau crossed on the drive.

• Distance: 5.8-mile loop

• Duration: 3-4 hours

• Elevation change: 300 feet

• Effort: moderate

• Trailhead: Shafer Canyon Overlook

The trail begins near the Shafer Canyon Overlook and loops down Taylor Canyon to Neck and Cabin Springs, formerly used by ranchers (look for the remains of the old cowboy cabin near Cabin Springs), then climbs back to Island in the Sky Road at a second trailhead 0.5 miles south of the start. A brochure should be available at the trailhead. Water at the springs supports maidenhair fern and other plants. Also watch for birds and wildlife attracted to this spot. Bring water with you, as the springs are not potable.

• Distance: 10.5 miles one-way to the Colorado River

• Duration: overnight

• Elevation change: 2,000 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: on the left, 1.3 miles past the neck

This is the only marked hiking route going all the way from Island in the Sky to the Colorado River. The first 2.5 miles cross Gray’s Pasture to the rim, which affords fantastic vistas over the Colorado River. From here, the trail descends steeply, dropping 1,600 feet over the next 2.5 miles, to White Rim Road, a little less than seven miles from the trailhead. Part of this section follows an old mining road past several abandoned mines, all relics of the uranium boom. Don’t enter the shafts; they’re in danger of collapse and may contain poisonous gases. From the mining area, the route descends through a wash to White Rim Road, follows the road a short distance south, then goes down Lathrop Canyon Road to the Colorado River, another four miles and 500 vertical feet. The trail has little shade and can be very hot. Vehicular traffic may be encountered along the White Rim Road portion of the trail. For a long day hike (13.6 miles round-trip), turn around when you reach the White Rim Road and hike back up to the top of the mesa.

• Distance: 0.25 miles one-way

• Duration: 30 minutes

• Elevation change: 80 feet

• Effort: easy

• Trailhead: on the left, 5.5 miles from the neck

A short hike leads to the clifftop Mesa Arch.

This easy trail leads to a spectacular arch on the rim of the mesa. On the way, the road crosses the grasslands and scattered juniper trees of Gray’s Pasture. A trail brochure available at the start describes the ecology of the mesa. The sandstone arch frames views of rock formations below and the La Sal Mountains in the distance. Photographers come here to catch the sun rising through the arch.

• Distance: 11-mile loop

• Duration: 5-7 hours

• Elevation change: 1,100 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: Murphy Point

• Directions: From the Upheaval Dome junction on the main park road, head three miles south. Turn right onto a rough dirt road and follow it 1.7 miles to Murphy Point.

Murphy Trail starts as a jaunt across the mesa, then drops steeply from the rim down to White Rim Road. This strenuous route forks partway down; one branch follows Murphy Hogback (a ridge) to Murphy Campground on the 4WD road, and the other follows a wash to the road one mile south of the campground.

• Distance: 0.75 miles one-way

• Duration: 1 hour

• Elevation change: 25 feet

• Effort: easy

• Trailhead: Grand View Picnic Area

Hike east along a peninsula to an overlook of Monument Basin and beyond. There are also good views of White Rim Road and potholes.

• Distance: 2.5 miles one-way

• Duration: 5 hours

• Elevation change: 1,400 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: Grand View Picnic Area

Gooseberry Trail drops off the mesa and makes an extremely steep descent to White Rim Road, just north of Gooseberry Campground. The La Sal Mountains are visible from the trail.

• Distance: 1 mile one-way

• Duration: 2 hours

• Elevation change: 50 feet

• Effort: easy

• Trailhead: Grand View Point Overlook

At the overlook, Grand View Trail continues past the end of the road for other vistas from the point, which is the southernmost tip of Island in the Sky. This short hike across the slickrock will really give you a feel for the entire Canyonlands National Park. From the mesa-top trail, you’ll see the gorges of the Colorado and Green Rivers come together; across the chasm is the Needles District. Look down to spot vehicles traveling along the White Rim Trail at the base of the mesa.

• Distance: 1 mile one-way

• Duration: 1.5 hours

• Elevation change: 200 feet

• Effort: moderate

• Trailhead: Aztec Butte parking area, 1 mile northwest of road junction on Upheaval Dome Road

It’s a bit of a haul up the slickrock to the top of this sandstone butte, but once you get here, you’ll be rewarded with a good view of the Island and Taylor Canyon. Atop the butte a loop trail passes several Anasazi granaries. Aztec Butte is one of the few areas in Island in the Sky with Native American ruins; the shortage of water in this area prevented permanent settlement.

• Distance: 0.5 miles one-way

• Duration: 1 hour

• Elevation change: 100 feet

• Effort: easy-moderate

• Trailhead: Upheaval Dome Road, on the right, 4.4 miles northwest of the road junction

A relatively easy trail climbs Whale Rock, a sandstone hump near the outer rim of Upheaval Dome. In a couple of places you’ll have to do some scrambling up the slickrock, which is made easier and a bit less scary thanks to handrails. From the top of the rock, there are good views of the dome.

• Distance: 1 mile one-way

• Duration: 1.5 hours

• Elevation change: 150 feet

• Effort: easy

• Trailhead: Upheaval Dome parking area

The trail leads to Upheaval Dome overviews; it’s about 0.5 miles to the first overlook and a mile to the second. The shorter trail leads to the rim with a view about 1,000 feet down into the jumble of rocks in the craterlike center of Upheaval Dome. The longer trail descends the slickrock and offers even better views. Energetic hikers can explore this formation in depth by circling it on the Syncline Loop Trail or from White Rim Road below.

• Distance: 8-mile loop

• Duration: 5-7 hours

• Elevation change: 1,200 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: Upheaval Dome parking area

Syncline Loop Trail makes a circuit completely around Upheaval Dome. The trail crosses Upheaval Dome Canyon about halfway around from the overlook; walk east 1.5 miles up the canyon to enter the crater itself. This is the only nontechnical route into the center of the dome. A hike around Upheaval Dome with a side trip to the crater totals 11 miles, and it is best done as an overnight trip. Carry plenty of water for the entire trip; this dry country can be very hot in summer. The Green River is the only reliable source of water. An alternate approach is to start near Upheaval Campsite on White Rim Road; hike four miles southeast on through Upheaval Canyon to a junction with the Syncline Loop Trail, then another 1.5 miles into the crater. The elevation gain is about 600 feet.

• Distance: 10 miles one-way

• Duration: overnight

• Elevation change: 1,500 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: 1.5 miles southeast of the Upheaval Dome parking area

Alcove Spring Trail connects with White Rim Road in Taylor Canyon. Five miles of the 10-mile distance is on the steep trail down through Trail Canyon and five miles is on a jeep road in Taylor Canyon. One downside of this trail is the 4WD traffic, which can be pretty heavy during the spring and fall. From the Taylor Canyon end of the trail, it is not far to the Upheaval Trail, which heads southeast to its junction with the Syncline Trail, which in turn leads to the Upheaval Dome parking area. Allow at least one overnight if you plan to hike this full loop. Day hikers should plan to turn around after the first five-mile section; this is still a very full day of hiking. Carry plenty of water—the trail is hot and dry.

There is only one developed campground in the Island in the Sky District. Willow Flat Campground on Murphy Point Road has only 12 sites ($10), available on a first-come, first-served basis; sites tend to fill up in all seasons except winter. No water or services are available.

Camping is available outside the park at Dead Horse Point State Park (reservations 800/322-3770, www.reserveamerica.com, $20 plus $9 reservations fee), which is also very popular, so don’t plan on getting a spot without reserving ahead. There are also primitive Bureau of Land Management (BLM) campsites along Highway 313.

The Needles District, named for the area’s distinctive sandstone spires, showcases some of the finest rock sculptures in Canyonlands National Park. Spires, arches, and monoliths appear in almost every direction. Prehistoric ruins and rock art exist in greater variety and quantity here than elsewhere in the park. Perennial springs and streams bring greenery to the desert.

While a scenic paved road leads to the district, this area of the park has only about a dozen miles of paved roads. Needles doesn’t have a lot to offer travelers who are unwilling to get out of their vehicles and hike; however, it’s the best section of the park for a wide variety of day hikes. Even a short hike opens up the landscape and leads to remarkable vistas and prehistoric sites.

To reach the Needles District, go 40 miles south from Moab (or 14 miles north of Monticello) on U.S. 191, turn west on Highway 211, and continue for 38 miles.

Stop at the visitors center (west end of Hwy. 211, 435/259-4711, 8am-4:30pm daily Nov.-Feb., longer hours Mar.-Oct.) for information on hiking, back roads, and other aspects of travel in the Needles, as well as backcountry permits, required for all overnight stays in the backcountry, and maps, brochures, and books. Take a moment to look at the little computer-animated slide show on the region’s geology—its graphics make it all become clear. When the office isn’t open, you’ll find information posted outside on the bulletin board.

Newspaper Rock preserves some of the richest, most fanciful prehistoric rock art in Utah.

Although not in the park itself, Newspaper Rock lies just 150 feet off Highway 211 on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land on the way to the Needles District. At Newspaper Rock, a profusion of petroglyphs depict human figures, animals, birds, and abstract designs. These represent 2,000 years of human history during which prehistoric people and Anasazi, Fremont, Paiute, Navajo, and Anglo travelers passed through Indian Creek Canyon. The patterns on the smooth sandstone rock face stand out clearly, thanks to a coating of dark desert varnish. A short nature trail introduces you to the area’s desert and riparian vegetation.

The cracks in the rock walls around Indian Creek offer world-class rock climbing; climbers should track down a copy of Indian Creek: A Climbing Guide, by David Bloom, for details and lots of pictures. Moab Desert Adventures (415 N. Main St., Moab, 435/260-2404 or 877/765-4273, www.moabdesertadventures.com) offers guided climbing at Indian Creek.

From U.S. 191 between Moab and Monticello, turn west on Highway 211 and travel 12 miles to Newspaper Rock. Indian Creek’s climbing walls start about three miles west of Newspaper Rock.

Although outside the park, these viewpoints atop the high mesa east of Canyonlands National Park offer magnificent panoramas of the surrounding area. Part of the BLM’s Canyon Rims Recreation Area (www.blm.gov), these easily accessed overlooks provide the kind of awe-inspiring vistas over the Needles District that would otherwise require a hike in the park. The turnoff for both overlooks is at milepost 93 on U.S. 191, which is 32 miles south of Moab and 7 miles north of Highway 211. There are also two campgrounds along the access road.

For the Needles Overlook, follow the paved road 22 miles west to its end (turn left at the junction 15 miles in). The BLM maintains a picnic area and interpretive exhibits here. A fence protects visitors from the sheer cliffs that drop off more than 1,000 feet. You can see much of Canyonlands National Park and southeastern Utah. Look south for the Sixshooter Peaks and the high country of the Abajo Mountains; southwest for the Needles (thousands of spires reaching for the sky); west for the confluence area of the Green and Colorado Rivers, the Maze District, the Orange Cliffs, and the Henry Mountains; northwest for the lazy bends of the Colorado River Canyon and the sheer-walled mesas of Island in the Sky and Dead Horse Point; north for the Book Cliffs; and northeast for the La Sal Mountains. The changing shadows and colors of the canyon country make for a continuous show throughout the day.

For the Anticline Overlook, continue straight north at the junction with the Needles road and drive 17 miles on a good gravel road to the fenced overlook at road’s end. You’ll be standing 1,600 feet above the Colorado River. The sweeping panorama over the canyons, the river, and the twisted rocks of the Kane Creek Anticline is nearly as spectacular as that from Dead Horse Point, only 5.5 miles west as the crow flies. Salt and other minerals of the Paradox Formation pushed up overlying rocks into the dome visible below. Down-cutting by the Colorado River has revealed the twisted rock layers. The Moab Salt Mine across the river to the north uses a solution technique to bring up potash from the Paradox Formation several thousand feet underground. Pumps then transfer the solution to the bluetinted evaporation ponds. Look carefully at the northeast horizon to see an arch in the Windows Section of Arches National Park, 16 miles away.

The BLM operates two campgrounds in the Canyon Rims Recreational Area. Hatch Point Campground (10 sites, water early May-mid-Sept., $12) has a scenic mesa-top setting just off the road to the Anticline Overlook, about nine miles north of the road junction. Closer to the highway is Windwhistle Campground (water early May-late Sept., $12); it’s six miles west of U.S. 191 on the Needles Overlook road.

A general store just outside the park boundary offers a campground (435/979-4007, www.canyonlandsneedlesoutpost.com, mid-Mar.-late Oct., $20 tent or RV, no hookups), groceries, ice, gas, propane, a café, showers ($3 campers, $7 noncampers), and pretty much any camping supply you might have left at home. The campground is a great alternative to the park; sites have a fair amount of privacy and great views onto the park’s spires. The turnoff from Highway 211 is one mile before the Needles visitors center.

The main paved park road continues 6.5 miles past the visitors center to Big Spring Canyon Overlook. On the way, you can stop at several nature trails or turn onto 4WD roads. The overlook takes in a view of slickrock-edged canyons dropping away toward the Colorado River.

The Needles District includes about 60 miles of backcountry trails. Many interconnect to provide all sorts of day-hike and overnight opportunities. Cairns mark the trails, and signs point the way at junctions. You can normally find water in upper Elephant Canyon and canyons to the east in spring and early summer, although whatever remains is often stagnant by midsummer. Always ask the rangers about sources of water, and don’t depend on its availability. Treat water from all sources, including springs, before drinking it. Chesler Park and other areas west of Elephant Canyon are very dry; you’ll need to bring all your water. Mosquitoes, gnats, and deer flies can be pesky late spring-midsummer, especially in the wetter places, so be sure to bring insect repellent. To plan your trip, obtain the small hiking map available from the visitors center, the National Geographic/Trails Illustrated’s Needles District map, or USGS topographic maps. Overnight backcountry hiking requires a permit ($30 per group). Permits can be hard to get at the last minute during the busy spring hiking season, but you can apply for your permit any time after mid-July for the following spring. Find permit applications on the Canyonlands website (www.nps.gov/cany).

Cave Spring Trail

• Distance: 0.3 miles round-trip

• Duration: 20 minutes

• Elevation change: 20 feet

• Effort: easy

• Trailhead: on the left, 0.4 miles past the visitors center

This is one of two easy hikes near the visitors center. It passes near a well-preserved Anasazi granary. A trail guide available at the start tells about the Anasazi and the local plants.

• Distance: 0.6 miles round-trip

• Duration: 45 minutes

• Elevation change: 50 feet

• Effort: easy

• Trailhead: Cave Spring

• Directions: Turn left 0.7 miles past the visitors center and follow signs about 1 mile to the trailhead.

Don’t miss the Cave Spring Trail, which introduces the geology and ecology of the park and leads to an old cowboy line camp. Pick up the brochure at the beginning. The loop goes clockwise, crossing some slickrock; two ladders assist hikers on the steep sections. Native Americans first used these rock overhangs for shelter, and faint pictographs still decorate the rock walls. Much later—from the late 1800s until the park was established in 1964—cowboys used these open caves as a line camp. The park service has recreated the line camp, just 50 yards in from the trailhead, with period furnishings and equipment. If you’re not up for the full hike, or would rather not climb ladders, the cowboy camp and the pictographs are just a five-minute walk from the trailhead.

This trail is a good introduction to hiking on slickrock and using rock cairns to find your way. Signs identify plants along the way.

• Distance: 0.6 miles round-trip

• Duration: 40 minutes

• Elevation change: 20 feet

• Effort: easy

• Trailhead: parking area on the left side of Big Spring Canyon Overlook Scenic Drive, five miles past the visitors center

Highlights of this hike across the slickrock are the many potholes dissolved in the Cedar Mesa sandstone. A brochure illustrates the fairy shrimp, tadpole shrimp, horsehair worms, snails, and other creatures that spring to life when rain fills the potholes. Desert varnish rims the potholes; it forms when water evaporates, leaving mineral residues on the surface of the rocks. In addition to the potholes, you’ll enjoy fine views of distant buttes from the trail.

• Distance: 2.4 miles round-trip

• Duration: 2 hours

• Elevation change: 150 feet

• Effort: easy-moderate

• Trailhead: parking area on the right side of Big Spring Canyon Overlook Scenic Drive, 6.2 miles past the visitors center

The Slickrock Trail leads north to a series of four viewpoints, including a panoramic view over much of southeastern Utah, and overlooks of Big Spring and Little Spring Canyons. As its name indicates, much of the trail is across slickrock, but there are enough pockets of soil to support a good springtime display of wildflowers. The trailhead is almost at the end of the paved road, where Big Spring Canyon Overlook, 6.5 miles past the visitors center, marks the end of the scenic drive but not the scenery.

The Slickrock Trail has several great viewpoints.

• Distance: 5.5 miles one-way

• Duration: 5 hours

• Elevation change: 1,250 feet

• Effort: moderate-strenuous

• Trailhead: Big Spring Canyon Overlook

The Confluence Overlook Trail begins at the end of the paved road and winds west to an overlook of the Green and Colorado Rivers 1,000 feet below; there’s no trail down to the rivers. The trail starts with some ups and downs, crossing Big Spring and Elephant Canyons, and follows a jeep road for a short distance. Much of the trail is through open country, so it can get quite hot. Higher points have good views of the Needles to the south. You might see rafts in the water or bighorn sheep on the cliffs. Except for a few short steep sections, this trail is level and fairly easy; it’s the length of this 10-mile round-trip to the confluence as well as the hot sun that make it challenging. A very early start is recommended in summer because there’s little shade. Carry water even if you don’t plan to go all the way. This enchanting country has lured many a hiker beyond his or her original goal.

• Distance: 5 miles one-way

• Duration: 5-6 hours

• Elevation change: 550 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: Squaw Flat trailhead

• Directions: A road to Squaw Flat Campground and Elephant Hill turns left 2.7 miles past the ranger station. The Squaw Flat trailhead sits a short distance south of the campground and is reached by a separate signed road. You can also begin from a trailhead in the campground itself.

Peekaboo Trail winds southeast over rugged up-and-down terrain, including some steep sections of slickrock (best avoided when wet, icy, or covered with snow) and a couple of ladders. There’s little shade, so carry water. The trail follows Squaw Canyon, climbs over a pass to Lost Canyon, then crosses more slickrock before descending to Peekaboo Campground on Salt Creek Road (accessible by 4WD vehicles). Look for Anasazi ruins on the way and rock art at the campground. A rockslide took out Peekaboo Spring, which is still shown on some maps. Options on this trail include a turnoff south through Squaw or Lost Canyon to make a loop of 8.75 miles or more.

• Distance: 3.75 miles one-way

• Duration: 4 hours

• Elevation change: 700 feet

• Effort: moderate

• Trailhead: parking area on the left of the main road, 5 miles past the visitors center

• Directions: A road to Squaw Flat Campground and Elephant Hill turns left 2.7 miles past the ranger station. The Squaw Flat Trailhead is a short distance south of the campground and is reached by a separate signed road. You can also begin from a trailhead in the campground itself.

Squaw Canyon Trail follows the canyon south. Intermittent water can often be found until late spring. You can take a connecting trail (Peekaboo, Lost Canyon, or Big Spring Canyon) or cross a slickrock pass to Elephant Canyon.

• Distance: 3.25 miles one-way

• Duration: 4-5 hours

• Elevation change: 360 feet

• Effort: moderate-strenuous

• Trailhead: parking area on the left of the main road, 5 miles past the visitors center

• Directions: A road to Squaw Flat Campground and Elephant Hill turns left 2.7 miles past the ranger station. The Squaw Flat trailhead sits a short distance south of the campground and is reached by a separate signed road. You can also begin from a trailhead in the campground itself.

Lost Canyon Trail is reached via Peekaboo or Squaw Canyon Trails and makes a loop with them. Lost Canyon is surprisingly lush, and you may be forced to wade through water. Most of the trail is in the wash bottom, except for a section of slickrock to Squaw Canyon.

• Distance: 3.75 miles one-way

• Duration: 4 hours

• Elevation change: 370 feet

• Effort: moderate-strenuous

• Trailhead: parking area on the left of the main road, 5 miles past the visitors center

• Directions: A road to Squaw Flat Campground and Elephant Hill turns left 2.7 miles past the ranger station. The Squaw Flat trailhead is a short distance south of the campground and is reached by a separate signed road. You can also begin from a trailhead in the campground itself.

Big Spring Canyon Trail crosses an outcrop of slickrock from the trailhead, then follows the canyon bottom to the head of the canyon. It’s a lovely springtime hike with lots of flowers, including the fragrant cliffrose. Except in summer, you can usually find intermittent water along the way. At canyon’s end, a steep slickrock climb leads to Squaw Canyon Trail and back to the trailhead for a 7.5-mile loop. Another possibility is to turn southwest to the head of Squaw Canyon, then hike over a saddle to Elephant Canyon, for a 10.5-mile loop.

• Distance: 3 miles one-way

• Duration: 3-4 hours

• Elevation change: 920 feet

• Trailhead: Elephant Hill parking area or Squaw Flat trailhead (increases the distance slightly)

• Directions: Drive west 3 miles past the Squaw Flat campground turnoff (on passable dirt roads) to the Elephant Hill picnic area and trailhead at the base of Elephant Hill.

The Elephant Hill parking area doesn’t always inspire confidence: Sounds of racing engines and burning rubber can often be heard from above as vehicles attempt the difficult 4WD road that begins just past the picnic area. However, the noise quickly fades as you hit the trail. Chesler Park is a favorite hiking destination. A lovely desert meadow contrasts with the red and white spires that give the Needles District its name. An old cowboy line camp is on the west side of the rock island in the center of the park. The trail winds through sand and slickrock before ascending a small pass through the Needles to Chesler Park. Once inside, you can take the Chesler Park Loop Trail (5 miles) completely around the park. The loop includes the unusual 0.5-mile Joint Trail, which follows the bottom of a very narrow crack. Camping in Chesler Park is restricted to certain areas; check with a ranger.

• Distance: 5.5 miles one-way

• Duration: 5-7 hours

• Elevation change: 1,000 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: Elephant Hill parking area or Squaw Flat trailhead (increases the round-trip distance by 2 miles)

• Directions: Drive west 3 miles past the Squaw Flat campground turnoff (on passable dirt roads) to the Elephant Hill picnic area and trailhead at the base of Elephant Hill.

Druid Arch reminds many people of the massive slabs at Stonehenge in England, which are popularly associated with the druids. Follow the Chesler Park Trail two miles to Elephant Canyon, turn up the canyon for 3.5 miles, and then make a steep 0.25-mile climb, which includes a ladder and some scrambling, to the arch. Upper Elephant Canyon has seasonal water but is closed to camping.

• Distance: 9.5 miles one-way

• Duration: 2 days

• Elevation change: 1,000 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: Elephant Hill parking area or Squaw Flat trailhead (increases the distance by 2 miles)

• Directions: Drive west 3 miles past the Squaw Flat campground turnoff (on passable dirt roads) to the Elephant Hill picnic area and trailhead at the base of Elephant Hill.

Lower Red Lake Canyon Trail provides access to the Colorado River’s Cataract Canyon. This long, strenuous trip is best suited for experienced hikers and is ideally completed in two days. Distance from the Elephant Hill trailhead is 19 miles round-trip; you’ll be walking on 4WD roads and trails. If you can drive Elephant Hill 4WD Road to the trail junction in Cyclone Canyon, the hike is only eight miles round-trip. The most difficult trail section is a steep talus slope that drops 700 feet in 0.5 miles into the lower canyon. The canyon has little shade and lacks any water source above the river. Summer heat can make the trip grueling; temperatures tend to be 5-10°F hotter than on other Needles trails. The river level drops between midsummer and autumn, allowing hikers to go along the shore both downstream to see the rapids and upstream to the confluence. Undertows and strong currents make the river dangerous to cross.

• Distance: 12 miles one-way

• Duration: 2 days

• Elevation change: 1,650 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: end of Salt Creek Road

• Directions: Drive to the end of the rugged 13.5-mile 4WD road up Salt Creek to start this hike.

Several impressive arches and many inviting side canyons attract adventurous hikers to the extreme southeast corner of the Needles District. The trail goes south 12 miles up-canyon to Cottonwood Canyon and Beef Basin Road near Cathedral Butte, just outside the park boundary. The trail is nearly level except for a steep climb at the end. Water can usually be found. Some wading and bushwhacking may be necessary. The famous “All-American Man” pictograph, shown on some topographic maps (or ask a ranger), is in a cave a short way off to the east at about the midpoint of the trail; follow your map and unsigned paths to the cave, but don’t climb in—it’s dangerous to you, the ruins, and the pictograph inside. Many more archaeological sites are near the trail, but they’re all fragile, and great care should be taken when visiting them.

Visitors with bicycles or 4WD vehicles can explore the many backcountry roads that lead to the outback. More than 50 miles of challenging roads link primitive campsites, remote trailheads, and sites with ancient cultural remnants. Some roads in the Needles District are rugged and require previous experience in handling 4WD vehicles on steep inclines and in deep sand. Be aware that towing charges from this area commonly run over $1,000.

The best route for mountain bikers is the seven-mile-long Colorado Overlook Road, which starts near the visitors center. Although very steep for the first stretch and busy with 4WD vehicles spinning their wheels on the hill, Elephant Hill Road is another good bet, with just a few sandy parts. Start here and do a combination ride and hike to the Confluence Overlook. It’s about eight miles from the Elephant Hill parking area to the confluence; the final 0.5 miles is on a trail, so you’ll have to lock up your bike and walk this last bit. Horse Canyon and Lavender Canyon are too sandy for pleasant biking.

All motor vehicles and bicycles must purchase a $10 day-use permit and remain on designated roads. Overnight backcountry trips with bicycles or motor vehicles require a permit ($30 per group).

This rugged route begins near Cave Spring Trail, crosses sage flats for the next 2.5 miles, and then terminates at Peekaboo campground. Hikers can continue south into a spectacular canyon on Upper Salt Creek Trail.

Horse Canyon 4WD Road turns off to the left shortly before the mouth of Salt Canyon. The round-trip distance, including a side trip to Tower Ruin, is about 13 miles; other attractions include Paul Bunyan’s Potty, Castle Arch, Fortress Arch, and side canyon hiking. Salt and Horse Canyons can easily be driven in 4WD vehicles. Salt Canyon is usually closed in summer because of quicksand after flash floods and in winter due to shelf ice.

Both canyons are accessed via Davis Canyon Road off Highway 211; contain great scenery, arches, and Native American historic sites; and are easily visited with high-clearance vehicles. Davis is about 20 miles round-trip, while sandy Lavender Canyon is about 26 miles round-trip. Try to allow plenty of time in either canyon, because there is much to see and many inviting side canyons to hike. You can camp on BLM land just outside the park boundaries, but not in the park itself.

This popular route begins beside the visitors center and follows Salt Creek to Lower Jump Overlook. It then bounces across slickrock to a view of the Colorado River, upstream from the confluence. Driving, for the most part, is easy-moderate, although it’s very rough for the last 1.5 miles. Round-trip distance is 14 miles. This is also a good mountain bike ride.

camping in style at Needles Outpost

This rugged backcountry road begins three miles past the Squaw Flat Campground turnoff. Only experienced drivers with stout vehicles should attempt the extremely rough and steep climb up Elephant Hill (coming up the back side of Elephant Hill is even worse). The loop is about 10 miles round-trip. Connecting roads go to the Confluence Overlook trailhead (the viewpoint is one mile round-trip on foot), the Joint trailhead (Chesler Park is two miles round-trip on foot), and several canyons. Some road sections on the loop are one-way. The parallel canyons in this area are grabens caused by faulting, where a layer of salt has shifted deep underground. In addition to Elephant Hill, a few other difficult spots must be negotiated.

This area can also be reached by a long route south of the park using Cottonwood Canyon and Beef Basin Road from Highway 211, about 60 miles one-way. You’ll enjoy spectacular vistas from the Abajo Highlands. Two very steep descents from Pappys Pasture into Bobbys Hole effectively make this section one-way; travel from Elephant Hill up Bobbys Hole is possible but much more difficult than going the other way, and it may require hours of road-building. The Bobbys Hole route may be impassable at times; ask about conditions at the BLM office in Monticello or at the Needles visitors center.

The Squaw Flat Campground (year-round, no reservations, $15) about six miles from the visitors center, has 26 sites, many snuggled under the slickrock, and has water. RVs must be less than 28 feet long. Rangers present evening programs at the campfire circle on Loop A spring through autumn.

If you can’t find a space at Squaw Flat, a common occurrence in spring and fall, the private campground at Needles Outpost (435/979-4007, www.canyonlandsneedlesoutpost.com, mid-Mar.-late Oct., $20 tents or RVs, no hookups, showers $3), just outside the park entrance, is a good alternative.

Nearby BLM land also offers a number of places to camp. A string of campsites along Lockhart Basin Road are convenient and inexpensive. Lockhart Basin Road heads north from Highway 211 about five miles east of the entrance to the Needles District. Hamburger Rock Campground (no water, $6) is about one mile up the road. North of Hamburger Rock, camping is dispersed, with many small (no water, free) campsites at turnoffs from the road. Not surprisingly, the road gets rougher the farther north you travel; beyond Indian Creek Falls, it’s best to have 4WD. These campsites are very popular with climbers who are here to scale the walls at Indian Creek.

There are two first-come, first-served campgrounds ($12) in the Canyon Rims Special Recreation Management Area (www.blm.gov). Windwhistle Campground, backed by cliffs to the south, has fine views to the north and a nature trail; follow the main road from U.S. 191 for six miles and turn left. At Hatch Point Campground, in a piñon-juniper woodland, you can enjoy views to the north. Go 24 miles in on the paved and gravel roads toward Anticline Overlook, then turn right and continue for one mile. Both campgrounds have water mid-April-mid-October, tables, grills, and outhouses.

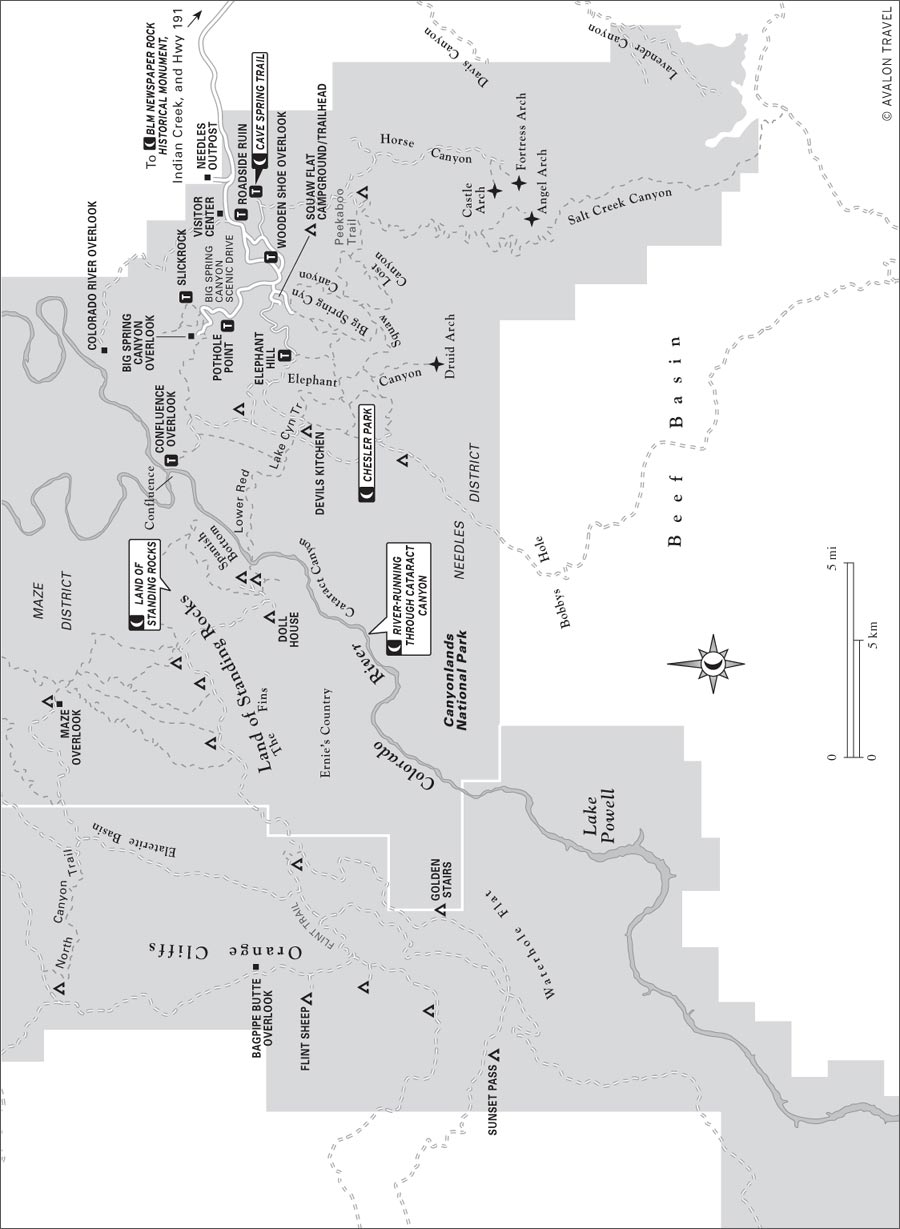

Only adventurous and experienced travelers will want to visit this rugged land west of the Green and Colorado Rivers. Vehicle access wasn’t even possible until 1957, when mineral-exploration roads first entered what later became Canyonlands National Park. Today, you’ll need a high-clearance 4WD vehicle, a horse, or your own two feet to get around, and most visitors spend at least three days in the district. The National Park Service plans to keep this district in its remote and primitive condition. An airplane flight, which is recommended if you can’t come overland, provides the only easy way to see the scenic features.

The names of erosional forms describe the landscape—Orange Cliffs, Golden Stairs, the Fins, Land of Standing Rocks, Lizard Rock, the Doll House, Chocolate Drops, the Maze, and Jasper Canyon. The many-fingered canyons of the Maze gave the district its name; although it is not a true maze, the canyons give that impression. It is extremely important to have a good map before entering this part of Canyonlands. National Geographic/Trails Illustrated makes a good one, called Canyonlands National Park Maze District, NE Glen Canyon NRA.

Dirt roads to the Hans Flat Ranger Station (435/259-2652, 8am-4:30pm daily) and Maze District branch off from Highway 24 (across from the Goblin Valley State Park turnoff) and Highway 95 (take the usually unmarked Hite-Orange Cliffs Road between the Dirty Devil and Hite Bridges at Lake Powell). The easiest way in is the graded 46-mile road from Highway 24; it’s fast, although sometimes badly corrugated. The 4WD Hite Road (also called Orange Cliffs Rd.) is longer, bumpier, and, for some drivers, tedious; it’s 54 miles from the turnoff at Highway 95 to the Hans Flat Ranger Station via the Flint Trail. All roads to the Maze District cross Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. From Highway 24, two-wheel-drive vehicles with good clearance can travel to Hans Flat Ranger Station and other areas near, but not actually in, the Maze District. From the ranger station it takes at least three hours of skillful four-wheeling to drive into the canyons of the Maze.

One other way of getting to the Maze District is by river. Tex’s Riverways (435/259-5101 or 877/662-2839, www.texsriverways.com, about $110 pp) can arrange a jet-boat shuttle on the Colorado River from Moab to the Spanish Bottom. After the two-hour boat ride, it’s 1,260 vertical feet uphill in a little over one mile to the Doll House via the Spanish Bottom Trail.

Maze District explorers need a backcountry permit ($30) for overnight trips. Note that a backcountry permit in this district is not a reservation. You may have to share a site, especially in the popular spring months. As in the rest of the park, only designated sites can be used for vehicle camping. You don’t need a permit to camp in the adjacent Glen Canyon National Recreation Area (NRA) or on BLM land.

There are no developed sources of water in the Maze District. Hikers can obtain water from springs in some canyons (check with a ranger to find out which are flowing) or from the rivers; purify all water before drinking. The Maze District has nine camping areas (two at Maze Overlook, seven at Land of Standing Rocks), each with a 15-person, three-vehicle limit.

The National Geographic/Trails Illustrated topographic map of the Maze District describes and shows the few roads and trails here; some routes and springs are marked on it too. Agile hikers experienced in desert and canyon travel may want to take off on cross-country routes, which are either unmarked or lightly cairned.

Extra care and preparation must be undertaken for travel in both Glen Canyon NRA and the Maze. Always ask rangers beforehand for current conditions. Be sure to leave an itinerary with someone reliable who can contact the rangers if you’re overdue returning. Unless the rangers know where to look for you in case of breakdown or accident, a rescue could take weeks.

Here in the heart of the Maze District, strangely shaped rock spires stand guard over myriad canyons. Six camping areas offer scenic places to stay (permit required). Hikers have a choice of many ridge and canyon routes from the 4WD road, a trail to a confluence overlook, and a trail that descends to the Colorado River near Cataract Canyon.

Getting to the Land of Standing Rocks takes some careful driving, especially on a three-mile stretch above Teapot Canyon. The many washes and small canyon crossings here make for slow going. Short-wheelbase vehicles have the easiest time, of course. The turnoff for Land of Standing Rocks Road is 6.6 miles from the junction at the bottom of the Flint Trail via a wash shortcut (add about three miles if driving via the four-way intersection). The lower end of the Golden Stairs foot trail is 7.8 miles in; the western end of the Ernies Country route trailhead is 8.6 miles in; the Wall is 12.7 miles in; Chimney Rock is 15.7 miles in; and the Doll House is 19 miles in, at the end of the road. If you drive from the south on Hite-Orange Cliffs Road, stop at the self-registration stand at the four-way intersection, about 31 miles in from Highway 95; you can write your own permit for overnights in the park.

Tall, rounded rock spires near the end of the road reminded early visitors of dolls, hence the name Doll House. The Doll House is a great place to explore, or you can head out on nearby routes and trails.

Hans Flat Ranger Station and this peninsula, which reaches out to the east and north, are at an elevation of about 6,400 feet. Panoramas from North Point take in the vastness of Canyonlands, including the Maze, Needles, and Island in the Sky Districts. From Millard Canyon Overlook, just 0.9 miles past the ranger station, you can see arches, Cleopatra’s Chair, and features as distant as the La Sal Mountains and Book Cliffs. For the best views, drive out to Panorama Point, about 10.5 miles one-way from the ranger station. A spur road to the left goes two miles to Cleopatra’s Chair, a massive sandstone monolith and area landmark.

• Distance: 7 miles one-way

• Duration: overnight

• Elevation change: 1,000 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: on North Point Road

• Directions: From Hans Flat Ranger Station, drive 2.5 miles east, turn left onto North Point Road, and continue about 1 mile to the trailhead.

This is just about the only trailhead in the Maze District that two-wheel-drive vehicles can usually reach. The trail leads down through the Orange Cliffs. At the eastern end of the trail, ambitious hikers can follow 4WD roads an additional six miles to the Maze Overlook Trail, then one more mile into a canyon of the Maze. Because North Point belongs to the Glen Canyon NRA, you can camp here without a permit.

• Distance: 3 miles one-way (to Harvest Scene)

• Duration: 3-4 hours

• Elevation change: 550 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: at the end of the road in the Maze District

Here, at the edge of the sinuous canyons of the Maze, the Maze Overlook Trail drops one mile into the South Fork of Horse Canyon; bring a 25-foot-long rope to help lower backpacks through one difficult section. Once in the canyon, you can walk around to the Harvest Scene, a group of prehistoric pictographs, or do a variety of day hikes or backpacking trips. These canyons have water in some places; check with the ranger when you get your permit. At least four routes connect with the 4WD road in Land of Standing Rocks, shown on the Trails Illustrated map. Hikers can also climb Petes Mesa from the canyons or head downstream to explore Horse Canyon, but a dry fall blocks access to the Green River. You can stay at primitive camping areas (backcountry permit required) and enjoy the views.

• Distance: 2 miles one-way

• Duration: 3 hours

• Elevation change: 800 feet

• Effort: moderate

• Trailhead: bottom of Flint Trail, at Golden Stairs camping area

• Directions: Drive the challenging Flint Trail, a 4WD route, to its bottom. The top of the Golden Stairs is 2 miles east of the road junction at the bottom of the Flint Trail.

Hikers can descend this steep foot trail to the Land of Standing Rocks Road in a fraction of the time it takes for drivers to follow the roads. The trail offers good views of Ernies Country, the vast southern area of the Maze District, but it lacks shade or water. The eponymous stairs are not actual steps carved into the rock, but a series of natural ledges.

• Distance: 4.5 miles one-way

• Duration: 5 hours

• Elevation change: 550 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: Chocolate Drops

• Directions: The Land of Standing Rocks turnoff is 6.6 miles from the junction at the bottom of the Flint Trail. The trailhead is just east of the Wall camping area.

The well-named Chocolate Drops can be reached by a trail from the Wall near the beginning of the Land of Standing Rocks. A good day hike makes a loop from Chimney Rock to the Harvest Scene pictographs; take the ridge route (toward Petes Mesa) in one direction and the canyon fork northwest of Chimney Rock in the other. Follow your topographic map through the canyons and the cairns between the canyons and ridge. Other routes from Chimney Rock lead to lower Jasper Canyon (no river access) or into Shot and Water Canyons and on to the Green River.

• Distance: 1.2 miles one-way

• Duration: 3 hours

• Elevation change: 1,260 feet

• Effort: strenuous

• Trailhead: Doll House, near Camp 1, just before the end of the Land of Standing Rocks Road

This trail drops steeply to Spanish Bottom beside the Colorado River; a thin trail leads downstream into Cataract Canyon and the first of a long series of rapids. Surprise Valley Overlook Trail branches to the right off the Spanish Bottom Trail after about 300 feet and winds south past some dolls to a T junction (turn right for views of Surprise Valley, Cataract Canyon, and beyond); the trail ends at some well-preserved granaries, after 1.5 miles one-way. From the same trailhead, the Colorado-Green River Overlook Trail heads north five miles one-way from the Doll House to a viewpoint of the confluence. See the area’s Trails Illustrated map for routes, trails, and roads.

This narrow, rough 4WD road connects the Hans Flat area with the Maze Overlook, Doll House, and other areas below. The road, driver, and vehicle should all be in good condition before attempting this route. Winter snow and mud close the road late December-March, as can rainstorms anytime. Check on conditions with a ranger before you go. If you’re starting from the top, stop at the signed overlook just before the descent to scout for vehicles headed up (the Flint Trail has very few places to pass). The top of the Flint Trail is 14 miles south of Hans Flat Ranger Station; at the bottom, 2.8 nervous miles later, you can turn left and go two miles to the Golden Stairs Trailhead or 12.7 miles to the Maze Overlook; keep straight 28 miles to the Doll House or 39 miles to Highway 95.

This canyon contains exceptional prehistoric rock art in a separate section of Canyonlands National Park. Ghostly life-size pictographs in the Great Gallery provide an intriguing look into the past. Archaeologists think that the images had religious importance, although the meaning of the figures remains unknown. The Barrier Canyon Style of these drawings has been credited to an archaic culture beginning at least 8,000 years ago and lasting until about AD 450. Horseshoe Canyon also contains rock art left by the subsequent Fremont and Anasazi people. The relationship between the earlier and later prehistoric groups hasn’t been determined.

Call the Hans Flat Ranger Station (435/259-2652) to inquire about ranger-led hikes to the Great Gallery (Sat.-Sun. spring); when staff are available, additional walks may be scheduled. In-shape hikers will have no trouble making the hike on their own, however.

some of the figures in the Great Gallery, the largest panel of pictographs and petroglyphs in the Horseshoe Canyon unit

• Distance: 3.25 miles one-way

• Duration: 4-6 hours

• Elevation change: 800 feet

• Effort: moderate-strenuous

• Trailhead: parking area on the canyon’s west rim

• Directions: From Highway 24, turn east across from the Goblin Valley State Park turnoff, then continue east 30 miles on a dirt road; keep left at the Hans Flat Ranger Station and Horseshoe Canyon turnoff 25 miles in.

Horseshoe Canyon is northwest of the Maze District. The easiest and most common way to reach Horseshoe Canyon is from the west and Highway 24. In dry weather, cars with good clearance can reach a trailhead on the canyon’s west rim. From the rim and parking area, the trail descends 800 feet in one mile on an old jeep road, which is now closed to vehicles. At the canyon bottom, turn right and go two miles upstream to the Great Gallery. The sandy canyon floor is mostly level; trees provide shade in some areas.

Look for other rock art along the canyon walls on the way to the Great Gallery. Take care not to touch any of the drawings, because they’re fragile and irreplaceable. The oil from your hands will remove the paints. Horseshoe Canyon also offers pleasant scenery and spring wildflowers. Carry plenty of water. Neither camping nor pets are allowed in the canyon, although horses are OK, but you can camp on the rim. Contact the Hans Flat Ranger Station or the Moab office for road and trail conditions.

Horseshoe Canyon can also be reached via primitive roads from the east. A 4WD road runs north 21 miles from Hans Flat Ranger Station and drops steeply into the canyon from the east side. The descent on this road is so rough that most people prefer to park on the rim and hike the last mile of road. A vehicle barricade prevents driving right up to the rock-art panel, but the 1.5-mile walk is easy. A branch off the jeep road goes to the start of Deadman’s Trail (1.5 miles one-way), which is less used and more difficult.

The River District is the name of the administrative unit of the park that oversees conservation and recreation for the Green and Colorado Rivers.

Generally speaking, there are two boating experiences on offer in the park’s River District. First are the relatively gentle paddling and rafting experiences on the Colorado and Green Rivers above their confluence. After these rivers meet, deep in the park, the resulting Colorado River then tumbles into Cataract Canyon, a white-water destination par excellence with abundant Class III-V rapids.

While rafting and canoeing enthusiasts can plan their own trips to any section of these rivers, by far the vast majority of people sign on with outfitters, often located in Moab, and let them do the planning and work. Do-it-yourselfers must start with the knowledge that permits are required for most trips but are not always easily procured; because these rivers flow through rugged and remote canyons, most trips require multiple days and can be challenging to plan.

No matter how you execute a trip through the River District, there are several issues to think about beforehand. There are no designated campsites along the rivers in Canyonlands. During periods of high water, camps can be difficult to find, especially for large groups. During late summer and fall, sandbars are usually plentiful and make ideal camps. There is no access to potable water along the river, so river runners either need to bring along their own water or be prepared to purify river water.

Rafters set out on the Colorado River.

While it’s possible to fish in the Green and Colorado Rivers, these desert rivers don’t offer much in the way of species that most people consider edible. You’ll need to bring along all your foodstuffs.

The park requires all river runners to pack out their solid human waste. Specially designed portable toilets that fit into rafts and canoes can be rented from most outfitters in Moab.

The Green and Colorado Rivers flow smoothly through their canyons above the confluence of the two rivers. Almost any shallow-draft boat can navigate these waters: Canoes, kayaks, rafts, and powerboats are commonly used. Any travel requires advance planning because of the remoteness of the canyons and the scarcity of river access points. No campgrounds, supplies, or other facilities exist past Moab on the Colorado River or the town of Green River on the Green River. All river runners must follow park regulations, which include carrying life jackets, using a fire pan for fires, and packing out all garbage and solid human waste. The river flow on both the Colorado and the Green Rivers averages a gentle 2-4 mph (7-10 mph at high water). Boaters typically do 20 miles per day in canoes and 15 miles per day on rafts.

The Colorado has one modest rapid, called the Slide (1.5 miles above the confluence), where rocks constrict the river to one-third of its normal width; the rapid is roughest during high water levels in May-June. This is the only difficulty on the 64 river miles from Moab. Inexperienced canoeists and rafters may wish to portage around it. The most popular launch points on the Colorado are the Moab Dock (just upstream from the U.S. 191 bridge near town) and the Potash Dock (17 miles downriver on Potash Rd./Hwy. 279).

On the Green River, boaters at low water need to watch for rocky areas at the mouth of Millard Canyon (33.5 miles above the confluence, where a rock bar extends across the river) and at the mouth of Horse Canyon (14.5 miles above the confluence, where a rock and gravel bar on the right leaves only a narrow channel on the left side). The trip from the town of Green River through Labyrinth and Stillwater Canyons is 120 miles. Launch points include Green River State Park (in the town of Green River) and Mineral Canyon (52 miles above the confluence and reached on a fair-weather road from Hwy. 313). Boaters who launch at Green River State Park pass through Labyrinth Canyon; a free interagency permit is required for travel along this stretch of the river. Permits are available from the BLM office (82 Dogwood Ave., Moab, 435/259-2100, 7:45am-noon Mon.-Fri.), the Canyonlands National Park Headquarters (2282 SW Resource Blvd., Moab, 435/719-2313, 8am-4pm Mon.-Fri.), Green River State Park in Green River, or the John Wesley Powell River History Museum (1765 E. Main St., Green River, 435/564-3427, 8am-7pm daily). A permit can also be downloaded from the BLM website (www.blm.gov).

No roads go to the confluence. The easiest return to civilization for nonmotorized craft is a pickup by jet boat from Moab by Tex’s Riverways (435/259-5101, www.texsriverways.com) or Tag-A-Long Tours (800/453-3292, www.tagalong.com). A far more difficult way out is hiking either of two trails just above the Cataract Canyon Rapids to 4WD roads on the rim. Don’t plan to attempt this unless you’re a very strong hiker and have a packable watercraft.

National park rangers require that boaters above the confluence obtain a backcountry permit ($30) either in person from the Moab National Park Service office (2282 SW Resource Blvd., Moab, 435/719-2313, 8am-4pm Mon.-Fri.) or by mail (National Park Service Reservation Office, 2282 SW Resource Blvd., Moab, UT 84532-3298) or fax (435/259-4285) at least two weeks in advance.

Notes on boating the Green and Colorado Rivers are available on request from the National Park Service’s Moab office (435/259-3911). Bill and Buzz Belknap’s Canyonlands River Guide has river logs and maps pointing out items of interest on the Green River below the town of Green River and all of the Colorado River from the upper end of Westwater Canyon to Lake Powell.

The Colorado River enters Cataract Canyon at the confluence and picks up speed. The rapids begin four miles downstream and extend for the next 14 miles to Lake Powell. Especially in spring, the 26 or more rapids give a wild ride equal to the best in the Grand Canyon. The current zips along at up to 16 mph and forms waves more than seven feet high. When the excitement dies down, boaters have a 34-mile trip across Lake Powell to Hite Marina; most people either carry a motor or arrange for a powerboat to pick them up. Depending on water levels, which can vary wildly from year to year, the dynamics of this trip and the optimal take-out point can change. Depending on how much motoring is done, the trip through Cataract Canyon takes 2-5 days.

Because of the real hazards of running the rapids, the National Park Service requires boaters to have proper equipment and a permit ($30). Many people go on commercial trips with Moab outfitters on which everything has been taken care of. Private groups must contact the Canyonlands River Unit of the National Park Service far in advance for permit details (435/259-3911, www.nps.gov/cany).