4

Facets of the Goddess

TO BETTER KNOW THE GREAT GODDESS, ancient peoples began to look at her through different lenses. Their perspectives yielded various archetypal roles, each one with its own personality and spiritual domain. These various aspects of the Great Goddess can be likened to the masks that she wears so that we, her worshippers, can better know her; indeed, through this relationship we can better know ourselves. This is the very nature of myth and religion: the Divine is transcendent, ineffable, and impersonal, but through personification and anthropomorphization, deities become the means for expressing the mysteries of the universe.

These individual aspects of the Great Goddess took on their own names, developed their own mythic stories, and were honored through specific rites of worship. Hard polytheists view each deity as a discrete divine being, believing that the ancient gods and goddesses named and worshipped throughout history are as real and distinct as you and me. Soft polytheists, on the other hand, view the separate divinities of cultures past and present as aspects of a single divine source. Soft polytheists regard all gods as one God, and all goddesses as one Goddess. This view holds that different pantheons represent the same archetypal roles espoused by the Great Goddess and her divine consort. Personally, I find myself straddling these two perspectives in my own practice. I relate to individual deities as the various masks worn by the Divine Feminine and the Divine Masculine; however, I also sincerely believe that eons of worship and prayer have actualized these separate deities as fully formed beings in their own right. Still, I don’t wholly subscribe to the idea that we as human beings are truly separate from one another or from Source; it stands to reason that the gods and goddesses are related to Source in the same way—as individuations of the Divine rather than as discrete entities. Ultimately, it is up to each practitioner to decide whether hard or soft polytheism—or a combination—supports her or his worldview.

One way to visualize the concept of soft polytheism is through the metaphor of a faceted gemstone, with each deity visualized as one of the facets polished into the stone. Every plane that is cut and polished enables you to look into the depths of the stone from a different angle. As these individual facets allow light to enter the heart of the gemstone, they also reflect and refract light, creating a radiant and luminous appearance. We can appreciate every facet for adding value to the gemstone, just as each individuation of the Great Goddess enables us to experience her magick and mystery. However, we must not confuse the facet for the light that it reflects; in the same way, the guises worn by the Goddess are not the transcendent spiritual experience itself, though they do provide the means to reach it.

Individual gods, goddesses, and spirits are not merely magickal correspondences. Through eons of reverence and preservation in lore and legend they have been etched into the collective consciousness. This makes them archetypal beings—forces that are universal, idealized, primal, but beings nonetheless. The gods and goddesses are stepping stones for reaching the ineffable. We do not simply add a goddess to the ingredients of a spell or ritual as we do herbs, oils, or gemstones. In spiritual practice our aim is to cultivate a conscious and conscientious relationship with the Divine, be it masculine, feminine, both, or neither. Thus, any tool that is aligned as a correspondence for a particular deity or spirit, be it a gemstone or any other object, is a vehicle for tapping into or enhancing the relationship with said being. In this way, crystals are powerful tools for invoking and evoking the Great Goddess in her many guises.

Few, if any, goddesses fit neatly into a single facet or archetype such as those described here. As cultures evolved and the lifestyles of their populations changed, their deities reflected these changes by adopting new characteristics. The exchange of ideas between cultures has also influenced the evolution of their gods and goddesses. For example, a goddess like Isis, whose worship has spread far beyond her original homeland of Egypt, has accrued many roles as a result of her adoration through the ages in many distant lands. Thus the archetypes explored in this chapter are merely starting points for relating to individual aspects of the Divine Feminine.

THE THREEFOLD GODDESS: MAIDEN, MOTHER, AND CRONE

In modern goddess spirituality, the best-known depiction of the Great Goddess appears in her threefold form: Maiden, Mother, and Crone. Triune deities are common the world over, but it was the work of poet and mythologist Robert Graves (1895–1985) who introduced the idea of this female trinity to the modern world, where it was absorbed by those who practice magick, witchcraft, and paganism. The three facets of Maiden, Mother, and Crone are related to the waxing, full, and waning phases of the moon—which is the life cycle of womankind and the flux of life in all of nature.

History is rife with examples of goddess trinities. Renowned mythologist Joseph Campbell (1904–1987) cites three distinct aspects of the Goddess in Paleolithic worship: she who gives life, she who receives us in death, and the initiatrix, who inspires spiritual and poetic realization.1 Hindu mythology speaks of the threefold nature of the Goddess as she who creates, she who sustains and transforms, and she who destroys. These ancient echoes of the nature of female divinity live on in today’s reverence for the Maiden, Mother, and Crone.

Triple goddesses are especially prominent in Celtic mythos. Morrigan is seen as comprised of the pagan goddesses Anu, Badb, and Macha. In Celtic Christianity we find that Saint Brigid—herself a remnant of the solar goddess Brigid—is often represented as the “three Saint Brigids.” We find three Zoryas in Slavic lore, one each as a goddess of the dawn, dusk, and midnight. The Roman goddess Carmenta is the central figure in a trinity of goddesses too. As the patron of childbirth, she represents the Mother, and her two sisters, named Antevorta (looking forward) and Postvorta (looking back), correspond to the Maiden and Crone, respectively.2

The Greek myths have dozens of triplicities, such as the three lunar goddesses Artemis, Selene, and Hekate. Though unrelated in a familial sense, they can be seen as representing the waxing, full, and waning or dark moon, respectively. Demeter, goddess of grains and growing things, and her daughter, Persephone, are part of several triads. Persephone, as the daughter, is the Maiden; Demeter is Matron; and Rhea, Demeter’s own mother, is a stand-in for the Crone. Likewise, the myths of Demeter and Persephone revolve around the latter’s descent into the underworld. Thus Persephone in her dual nature can represent both the innocence of the Maiden and the wisdom and transformation of the Crone when she assumes the role of Queen of the Underworld.

Recently there has been some criticism of the notion of the Triple Goddess, which charges that this model reduces the stages of a woman’s life to her reproductive cycle. Though the symbolism of the chaste Maiden, the fertile Mother, and the wizened Crone is traditional in Western occultism, it is important to bear in mind that these are archetypes; the lives of living women are rich and varied, and not every milestone fits this model. Much of contemporary paganism, especially British traditional witchcraft (such as Gardnerian Wicca), is inspired by fertility cults, which naturally center around the biologically driven symbols of sex and procreation. However, not all traditions of the craft nor all spiritual traditions that honor the Divine Feminine are based on the symbolism of fertility cults. Similarly, not all people have bodies that mirror the life cycle of Maiden-Mother-Crone. Bearing this in mind, the Triple Goddess can be a representation of metaphorical rather than biological themes of fertility and creation.

There are many examples of deities from cultures far and wide that fit the model of Maiden-Mother-Crone, either embodying a single facet of this trinity or by adopting all three roles at once. Like the cycle of the moon, the three aspects of the Triple Goddess represent the cycles of life in all its forms: genesis, sustenance, and death. These cycles repeat without end in nature, and out of this observation our ancestors first came to know the mysteries of the Goddess.

The Triple Goddess as expressed in stone is discussed in greater detail in chapter 5; the following is an overview of these three aspects of the Great Goddess.

The Maiden

Fair as flowers in the spring, the first face of the Triple Goddess is that of the Maiden. She is the embodiment of youth, freshness, and budding growth. Her beauty is radiant and spellbinding, and she is the dawning of a new day, ripe with the promise of fresh starts. The Maiden is independent, innocent, and ready to dive headlong into something new.

The Maiden starts the cycle of the Triple Goddess. She will one day grow into the role of Mother, who will, in turn, eventually reach the age of the elder Crone. To modern goddess worshippers, the Maiden is the embodiment of springtime and the waxing moon. She is the goddess of new beginnings, and her aid is called on for any working requiring increase, such as prosperity, love, and luck. Her carefree, capricious nature can inspire independence and empower witches and magick-makers to break free from limiting beliefs or situations.

Because she is typically seen as unmarried and has not yet birthed her firstborn, the Maiden cultivates love and eros, the sensual romantic instinct that drives us to find a partner. The Maiden is a virgin in the truest sense, unburdened by the conventional social obligation to marry and raise a family. This is the true nature of the virgin attendants of the Goddess throughout the ancient world—they fully owned their sexuality and owed it to no one but the Goddess. These priestesses were unattached and did not depend on their marital status to maintain their position in life. This threatened the early patriarchy, such that these priestesses were labeled “temple whores” and simply “prostitutes.”

Several archetypes have been born of the Maiden, including the Goddess of Love, who rules romance and beauty, as well as the Sacred Harlot, whose sexuality is dedicated to the Divine and who represents fertility incarnate. She oversees the hunt, for without her fertile embrace there is not enough wild game to feed the people. We know this Maiden as Artemis and Eos, as Aphrodite and Hestia, as Parvati and Oshún. The myth of Demeter and Persephone records the most famous of Maidens, Persephone, who is also called Kore, Greek for “maiden.”

To connect to the Maiden aspect of the Triple Goddess, work with gemstones that evoke images of springtime, growth, innocence, and new beginnings. Moss agate, aventurine, chalcedony, emerald, kambaba stone, kunzite, opal, peridot, fairy quartz, and sakura stone may be excellent tools. Peach and rainbow moonstone have a relationship with youth, growth, and innocence, so they are the most appropriate types of moonstone for the Maiden. Amethyst is a wonderful Maiden stone, as the origins of this stone’s name are found in the Greek myth about the nymph Amethyst, herself a maiden, who calls on Artemis (who is conflated with the Roman goddess Diana). Scarlet temple Lemurian seed crystals and copper-based stones integrate the independence, both sacred and sexual, of the Maiden, and they can be used for connecting to her energy.

The Mother

The Mother is easily the most revered aspect of the Triple Goddess. The life-giving, creative power of motherhood has always been revered as the holiest of holies. Cults devoted to the primal Mother are found worldwide, and many familiar goddesses are really just aspects of this archetype; she has been both the Bona Dea, “the Good Goddess,” and the Magna Mater, the “Great Mother.”

The Mother is both a creator and a sustainer of life. She provides for her children (and we are all her children) by nourishing, protecting, and teaching us how to survive. The Great Mother is the aspect of the Triple Goddess with the greatest number of faces. She is Isis, Gaia, Yemayá. She is known to others as Hera, Hathor, Demeter, and Frigg. She gives birth to the God and takes him as her sacred lover. The Mother receives his seed and transmutes it into new life, shaping the child in her womb just as seeds transform into the plants that grow in fertile soil. The Mother provides love and protection to her children, and she represents the mysteries of birth and transformation. By taking the God as her consort, she transforms him from a child to a man; her love, indeed, transmutes all.

Traditionally, the Mother has been associated with the many other archetypal roles of the Great Goddess. She is the patroness of hearth and home, and she is Earth Mother, the primal womb from which all life springs forth. The Mother is sometimes the goddess of the oceans and the abyss, for out of formless chaos is born land and sky in many of the world’s creation myths. She is also a goddess of the moon, especially at the height of the full moon, whose roundness alludes to the ripeness of a womb heavy with child. Earlier myths associate the Mother with the sun, for it is the light and warmth of the sun that provides energy and sustenance to all life forms.

The Mother is the divine arbiter; she is the bringer of truth and justice. She is the unknowable expanse of the sky and the darkness of the chthonic realms of our planet. The Divine Mother presides over every creative impulse, whether it is the birth of humans and animals, the sprouting of seeds, or the production of art and industry. Call on her when you need help in all creative endeavors.

Like the other facets of the Triple Goddess, the Matron has her dark, fierce aspects too. Scott and Janet Farrar write in The Witches’ Goddess that the “devouring Dark Mother is not evil; she is our friend, if we are not to stagnate and thus truly die, she urges us forward to new life, and to her other self, the Bright Mother.”3 She is the weeping Demeter, whose sorrow brings winter to the world. She is the Black Madonna. She is Kali. She is the darkness of the cave, her telluric womb. She is the void of space from which stars, planets, and moons are born. Since she grants life, she can also take it away. The Mother was depicted at Stone Age burials because tombs are symbolic of the womb; our remains are returned to the belly of the Great Mother so we can be reborn into our next life.

The Mother as life-giver and protectress is also a healer and wise woman. She is the Witch Mother and Queen of Heaven. These archetypal roles justify her primacy in rites of magick and initiation. She is the eternal tutor for all the magickal arts, and she implores her children to live within the rhythm of her cycles of life.

The stones of the Mother Goddess are many and varied, and they tend to be as luminous as the full moon. To tap into her radiant splendor try working with pearl, white or rainbow moonstone, selenite, moon quartz, clear quartz (especially spheres), and other white and transparent stones. Other gemstones associated with the Mother aspect of the Triple Goddess include aquamarine, biotite lens, carnelian, cuprite, emerald, fairy stone concretions, garnet, lapis lazuli, malachite, and rutilated quartz. Some chalcedonies, like the chrome-bearing nodules from Turkey and the earth-toned pieces from Morocco, also have a strong link to the Great Mother. Nourishing, loving stones invoke her energy, as do earthy, protective ones. Since all rocks, minerals, and crystals are pieces of the body of Mother Earth, each one, no matter the variety, can be used to tap into the energy of the Great Mother.

The Crone

Of the three facets of the Triple Goddess, I must confess that my most beloved is the Crone. Even in my teenage years I felt a strong kinship with her, and I often sought her aid in times of transition. Traditionally, the Crone represents the aged face of the Goddess. She is wisdom incarnate, and her vast experience makes her a fastidious and formidable teacher. She is the stereotypical hag-faced witch and the patroness of magickal arts. The Crone is linked to the waning cycles of life—the shrinking of the moon’s silver orb after its fullness and ripeness has passed and the shortening of the days (and consequent lengthening of the night) after the harvest has finished. This association with maturity, with receding and ending cycles, makes her the one who receives us in death. Thus it is the Crone who rules over initiation, for initiation is a symbolic death and rebirth.

The Crone represents the acquisition of wisdom that precedes transformation. When we open our hearts to her we can learn from experience. She is compassionate, as she has seen and known all the trials and challenges that life offers. She helps us meet these moments with cunning and compassion; her sagacity leads us on our own quest for wisdom. The Crone is typically connected to the darker aspects of the goddess, as the queen of witches and mistress of death. As depicted by the stiff Paleolithic nudes described in chapter 3, she is the psychopomp, the one who leads our souls to the other side after we shuffle off this mortal coil.

Crones and dark goddesses are found everywhere in the world’s myths. In Scotland, Ireland, and the Isle of Man there is the Cailleach Bhéare, the veiled hag who rules the winter. Slavic folklore records the Baba Yaga, the Crone-witch who is the liminal guardian on the hero’s journey. Goddesses associated with the darker aspects of human nature as well as the supernatural are sometimes relegated to the role of the Crone, no matter their age. Hekate, witch queen and ruler of the crossroads, is sometimes given the same role as the Crone. In the Afro-Caribbean pantheon, Yemayá is occasionally depicted as an old woman or hag, as well as a powerful witch and sorceress, as seen in her various emanations: Yemayá Aggana, Yemayá Awoyó, and Yemayá Okuti.

Out of the death, destruction, and darkness of the Crone, the Maiden is regenerated. In the forest, old logs decompose and return fertility to the soil for new plants to sprout. In the same fashion, the Crone honors death, knowing that it leads to rebirth. Darkness is needed to understand light, and the Crone provides the necessary balance so that we can experience the fullness and richness of the human experience. Through her fierce wisdom and altruistic compassion, the Crone initiates the witch in the greatest of all mysteries: that of death and rebirth.

The Crone’s crystals help to part the veil between the worlds. Many are dark in color, like the appearance of the dark moon. Some of my favorite stones for connecting to the Crone are obsidian and black moonstone, though one could also use jet, dark smoky quartz, and faden quartz. Holey stones (sometimes called “hag stones”) are traditionally associated with the Goddess in her guise as the Crone. Stones that help us connect with nonordinary reality, such as kyanite, jade, phantom quartz, and vivianite, also tap into the Crone’s wisdom. Fossils connect to the Crone through their age and sedimentary action; they are the whispers of the past that are etched in her memory. Lepidolite can represent the gentler, grandmotherly aspect of the Crone.

THE GODDESS ARCHETYPES

Archetype is a word that has taken on many layers of meaning. In its purest sense, the word denotes “an original pattern from which duplicates are made,” a definition based on the Greek archetupos, meaning “first-molded.” Archetypes are the literal and metaphorical blueprints—the idealized forms—of all of reality. In a material sense they can be prototypes from which objects are derived. From a literary perspective, archetypes are the symbols, motifs, and stories that recur without end in myth and story and art. In a psychological sense, archetypes are the subconscious ideas and symbols that humans inherit on a collective level; these patterns exist in our psyche and are ever-present.

Deities are archetypal in the truest sense of the word. They are the blueprints on which we model our myths, stories, and art. There are patterns and symbols that repeat all over the world, regardless of language, culture, and era. Similarly, the traits of these divine beings represent the psychological archetypes that we humans also embody. For these reasons, we are hard-pressed not to sort gods and goddesses into their many archetypes, such as Earth Mother or storm god.

Although deities the world over can be interpreted through the lens of their respective archetypal roles, these models do not define them absolutely. Any given goddess or god is more than just an archetype. It is possible that the individual gods of various pantheons began as unknowable archetypes in the subconscious minds of their worshippers. However, these figures have evolved and grown just as human culture has. Earth Mother figures are more than just personifications of nature; each has her own personality that has accrued through eons of worship.

By the same token, few deities fit neatly into a single archetypal category. You’ll often see goddesses wear the mantle of several archetypes, sometimes over the course of centuries and other times all at once. Hekate, for example, is sometimes a Maiden, sometimes a Crone; she rules the underworld and all things related to the moon and the heavens. Others may not fit neatly into any categories at all. Hard polytheists might argue that associating deities with their archetypes glosses over the individual temperaments and teachings that each offers. We must remember that although gods and goddesses do have certain archetypal qualities, they can also be viewed as individuals, just like you and me.

Examining these prototypic themes can help us, as human beings, relate to the unknowable, ineffable experience of divinity. To truly know any god or goddess we must find common ground on which to build a relationship; the archetypes offer solid ground for this kind of exploration.

The facets of the Great Goddess as seen in their various archetypes are described in this chapter. Use these delineations to help you navigate the numerous goddesses available to work with, as each archetype rules specific areas of our material and spiritual life. Some aspects of the Great Mother are better suited to specific magickal workings than others, so the following descriptions are intended to help you figure out which goddess is most appropriate for the work you have planned. The following entries on the archetypes will provide you with general information on the best stones and crystals to work with. These stones can be used in meditation, carried or worn, or worked with in spellcraft or ritual to invoke the presence of the Goddess. While most of these stones are listed in the compendium, several additional stones will be referenced throughout this chapter. Those not discussed elsewhere may relate to a very specific aspect of the Divine Feminine and not merit inclusion in the compendium itself.

The Earth Mother

As the personification of our planet, the Earth Mother is the most ancient aspect of the Great Goddess. To ancient peoples the Earth Mother was the Mother of All, for she nurtures and provides for all life. Today we know her as Mother Nature, though she is also the goddess of grains, the harvest, and the hunt. She is the primordial Mother from which all life arises, and she is the one who receives us in death, for we are returned to her womb when we are buried. The Earth Mother is Gaia, Freyja, and Danu. She is Demeter and Persephone (or Ceres and Proserpina to the Romans), goddesses of grains and harvests. In the Americas she is the corn mother and Mother Earth, known by different names according to different tribes. Many goddesses throughout the world are linked to Earth, including Isis, Inanna, and Asherah, while the primitive Venuses of the Paleolithic era are the first figurative representations of the Earth Mother.

Magickally, this aspect of the Goddess can be invoked for workings of fertility, prosperity, protection, and healing. Stones that are connected to the Earth Mother include aventurine, moss agate, azurite-malachite, jasper, chalcedony, emerald, fossil sea urchin (other fossils not discussed in the compendium, such as petrified wood, are also relevant), jade, jet, and serpentine.

Fierce Goddess

The Fierce Goddess is the mask worn by the huntress and the warrioress. She is the divine defender, the Maiden of the hunt as well as the Mother who channels the primal ferocity of the Divine Feminine. The Fierce Goddess may overlap with aspects of the Dark Goddess or Underworld Goddess (see subsequent descriptions of these archetypes), since they share many of the same traits.

Different cultures have visualized the Fierce Goddess in different roles. The Morrigan, a Celtic war goddess, embodies the power of the Fierce Goddess, with her battle cry and fearsome presence. The Amazons and Valkyries are also part of the family of warrior goddesses, as are Athena/Minerva, Macha, Badb, and Sekhmet. Inanna too was revered as a goddess of war in Sumeria. As the divine huntress, the Fierce Goddess is Artemis/Diana. She is also Brimwylf of Denmark, Dali of the Ossete people in southeastern Europe, and the Glaistig of Scotland. Oyá is the warrioress in several traditions of the African diaspora, and she is a powerful force of nature.

As the archetypal warrior, the Fierce Goddess can be invoked when you are experiencing conflict or wish to pursue your ambition. She provides motivation and action, and she is the fierce protectress of all her children. When you encounter dangerous situations, the Fierce Goddess can help you not only cope but thrive. She helps us transform fear and rage into raw fuel for inner and outer transformation. As the huntress, her magick helps us obtain our goals, and she is especially close to the animal kingdom.

Stones that embody the energy of the Fierce Goddess include amazonite (the gem of the Amazons) and many iron-rich stones like carnelian, hematite, and tiger’s eye. Obsidian, long used to make weapons, taps into the warrior energy of the Fierce Goddess, and its blackness reflects the dark themes of many of these goddesses. Other stones used to tap into the Fierce Goddess archetype include copper, pink tourmaline, and rutilated quartz.

Mistress of Magick

When the Goddess is honored as the patroness of the arts magickal, she wears the mantle of Mistress of Magick. She is the progenitor of all witches and magick-makers and is sometimes addressed as “Witch Mother” and “Queen of the Witches.” The Mistress of Magick is the archetype of the healer, oracle, wise woman, weaver of magicks, and walker-between-the-worlds.

The Mistress of Magick is a facet of the Great Goddess revered by those who live in the liminal spaces, on the fringes of society. This archetype often overlaps with other, more exoteric facets of the Goddess, including Underworld Goddess, the Queen of Heaven, and the Great Mother. She is the esoteric counterpart recognized by initiates. She is Isis and Inanna/Ishtar; she is Hekate, who rules the crossroads, the threshold between this world and the next. Often she is called Aradia or Diana. The Mistress of Magick is also Medea, Circe, Yemayá, Cerridwen, and Holle.

The Mistress of Magick is also the Fairy Queen, the ruler of the Shining Ones and wielder of their elder magick. In the British Isles, this figure is closely associated with witchcraft and fairy lore: there she is known variously as Mab (Medb, Maeve), Danu, Etain, the Lady of the Lake, Nimue, Titania, and countless other names. The title “Fairy Queen,” or “Queen of Elphame,” is sometimes given to the goddess Diana in some circles of modern witchcraft. As she who walks between the worlds, the Fairy Queen is naturally the patroness of witches and magick-makers.

The Mistress of Magick is invoked for rites of magick, worship, and transformation. She can be called on in virtually any of her individual forms for nearly all types of magickal workings. She can help open the doors to astral travel and otherworldly journeys, whether in ritual, meditation, or during the dream state. Petitioning her can lend power to your rites and may help you tap into your own innate power, or witch blood, for your magickal workings and ritual observances.

Crystals and gemstones connected to the Mistress of Magick archetype are quartz, moss agate, midnight lace obsidian, Romanian smoky quartz (wedding veil quartz), moon quartz, lapis lazuli, rainbow moonstone, vivianite, and carnelian. Staurolite, a mineral that forms cross-shaped, twinned crystals, symbolizes the crossroads and is thus a perfect tool for connecting with the Mistress of Magick archetype as well.

Goddess of Hearth and Home

The home has always been swaddled in the arms of the Great Mother. As the Goddess of Hearth and Home, she is the warmth and love that surrounds the home and all who dwell therein. Perhaps the reason that housekeeping, cooking, and raising families has been called “women’s work” is because of the intimate connection between the home and the Goddess herself.

Household shrines to gods and goddesses were once the cultural norm, and those dedicated to the Goddess of Hearth and Home have invited her blessings since prehistory. Among the best-known of goddesses in this archetypal role are the Greek Hestia (and her Roman counterpart, Vesta). The Celtic goddess Brigid protected against household fires and prevented mishaps in the kitchen. Holdja, a goddess of Estonian origin, lived on a roof beam and showered good luck on whoever greeted her upon entering the home. The rice goddesses of Asia, such as the Indian Annapurna, are often enshrined as household deities. Athena was originally a Minoan or Mycenaean household goddess who protected the family’s food supply, chased away pests, and strengthened the family bond.

The Goddess of Hearth and Home may be petitioned for health, healing, and protection of your family. She ensures household happiness, prosperity, and fertility. Many examples of this archetype double as aspects of the Mother Goddess and share her responsibilities.

Stones that connect to the Goddess of Hearth and Home include amber, aventurine, blue lace agate, geodes, holey stones, jasper, citrine, spirit quartz, and crystal clusters of many varieties.

Ocean Mother

The salty sea evokes the symbolism of the womb of the supernal Mother. Goddesses linked to the sea are common throughout the world. Water is a feminine element that symbolizes the emotions, especially love. Sometimes the Ocean Mother is the goddess of lakes, rivers, and ponds, as well as larger bodies of water. Ocean goddesses are often syncretized with lunar symbolism, since the moon rules the ocean’s tides.

Yemayá, from the Afro-Caribbean pantheon, is a prime example of the Ocean Mother, although her worship originated in Africa among the Yoruba as a goddess of the rivers and lakes. When Europeans enslaved the Yoruba and brought them to the New World, their beloved goddess was transformed into the Mother of the Oceans so she could journey with them. She is sometimes depicted as a mermaid and is thus conflated with other watery deities such as Ezili, Mami Wata, and Oshún. Other mythic figures that personify the Ocean Mother include Amphitrite, Greek mother of the monsters of the ocean; Anuket, of the Nile River; Saraswati and Ganga, both of the Hindu pantheon; and Chalchiuhtlicue, the Aztec jade-skirted goddess who rules over lakes, streams, and rain. (More Ocean Mother figures are described in the entry for aquamarine in chapter 7.)

Oceanic goddesses point to our birth from the aqueous environs of our mother’s womb, as well as from the primordial and chaotic abyss, the cosmic waters from which the whole of the world was born. Water endows us with an understanding of the gifts of flux and change. Water takes the shape of its vessel, and it is a universal solvent, thus water itself and the goddesses who personify it empower us to adapt and transform our lives.

Call on the aid of the Ocean Mother with gemstones such as aquamarine, mother-of-pearl, larimar, and coral. Amber, amazonite, copper, ocean jasper, and moonstone also have oceanic qualities that can be used to invoke the Ocean Mother.

Queen of Heaven

The moniker “Queen of Heaven” dates back to antiquity, when it was applied to a number of deities who served analogous functions among their worshippers. The Great Goddess is often referred to by this title among contemporary worshippers, who draw on an ancient tradition in doing so. The Queen of Heaven is the sovereign of the sky; her reign oversees sun and moon, clouds and stars.

Inanna, Anat, Isis, Astarte, Asherah, Ishtar, Frigg, Nuit, Hera, and Juno all claim the role of Queen of Heaven. Mazu, a Chinese sea goddess, is called “Empress of Heaven” by those who revere her. Such deities are often viewed as Mother Goddess figures as well; for this reason they often share traits with other divine mothers. Related archetypes include the goddesses of the sun, moon, and stars. Today, millions of people address the Virgin Mary as “Queen of Heaven,” thereby perpetuating this archetype. In fact, there is a Catholic shrine near my home in central Florida dedicated to Mary as Queen of the Universe. It is one of my favorite local spots to connect to the Divine Feminine.

Invoking the Queen of Heaven in your magickal workings can support endeavors related to rulership. She grants insight and can be petitioned for workings for nearly any aim.

The stones of the Queen of Heaven include amazonite, chrysocolla, copper, emerald, fossil sea urchin, lapis lazuli, malachite, nebula stone, clear quartz, veil of Isis quartz, sapphire, silver, turquoise, and yeh ming zhu.

Solar Goddess

Long ago, the sun, rather than the moon, was the heavenly body attributed to the Great Goddess in many cultures. The Solar Goddess is an aspect of the Queen of Heaven, and she is also usually an aspect of the Great Mother. The sun is the ultimate source of light, heat, energy, and life itself here on our planet, thus it is only natural that ancient peoples would revere the sun as the Goddess herself. In many languages the word for sun is feminine, attesting to its connection to the Divine Feminine.

Solar goddesses are many, although scholars once thought them an anomaly because the classical myths of Greece and Rome usually depict the sun as masculine and the moon as feminine. Solar goddesses include Sekhmet and Hathor from Egypt, the Japanese Amaterasu, Brigid and Rhiannon from the Celtic people, and the Baltic Saule, among many. The Solar Goddess archetype represents sovereignty, success, and power. Many sun goddesses are also creator deities who can confer their creativity on us.

Use solar gemstones such as amber, fire agate, orange calcite, creedite, copper, malachite, peridot, quartz, tiger’s eye, and turquoise for working with the Solar Goddess. Other stones connected to the sun include citrine, sunstone, pyrite, and ruby, as well as the metals gold and brass. Silver is occasionally linked to the Sun Goddess too.

Lunar Goddess

Arguably the most beloved aspect of the Goddess today is her manifestation as the Lunar Goddess. She is the embodiment of the ever-changing moon and the lover of the sun god. The moon’s phases link the Lunar Goddess to the three faces of the Triple Goddess: the Maiden represents the waxing moon, the Mother the full moon, and the Crone the waning moon. The Lunar Goddess is sometimes synonymous with the Queen of Heaven and the Mistress of Magick. She is truly the Great Mother known by many names the world over.

Perceiving the moon as an inherently feminine energy no doubt derives from the menstrual cycle as determined by the moon’s phases. In fact, the words menstruate and moon share an etymological root, the Latin mensis, “month.”*7 The archetype of the Moon Goddess is typified by the lunar aspect of classical goddesses like Artemis/Diana and Selene/Luna. Many other goddesses are also ascribed to the moon, including Isis, Hekate, Arianrhod, Ix Chel, Ch’ang O, Menil, Sina, and others.

Moon goddesses typically rule over the themes of magick and transformation, women’s mysteries, intuition, children, and the otherworldly realm of spirits, fairy folk, and other nonhuman beings. Lunar Goddess figures are usually honored during the esbats, or lunar celebrations, of traditional witchcraft. The Lunar Goddess is the initiatrix, the timekeeper, and the illuminatrix of the subconscious mind.

Lunar gemstones like moonstone and selenite are chief among the Lunar Goddess’s jewels. Spheres of rock crystal can also harness the power of the moon, and varieties of quartz such as moon quartz and white quartz also symbolize the moon’s magick. Pearls have long been visualized as miniature moons in their own right; they are excellent for contact with the Moon Mother. Yeh ming zhu, Chinese stones both natural and man-made that exhibit persistent phosphorescence—often fluorite or calcite—are sometimes called ming yueh zhu, meaning “bright moon pearl,” thus connecting to the lunar mysteries of the Great Goddess. Other gemstones with an overtly lunar energy include orbicular agate, moon quartz, chalcedony (especially white and gray), white coral, mother-of-pearl, aquamarine, opal, some forms of jasper, and sapphire.

Stellar Goddess

The Stellar Goddess archetype is often seen as an aspect of the Queen of Heaven. As the Star Goddess she is the central figure in the Faery (or Feri) Tradition, the branch of pagan witchcraft that arose in the United States in the 1960s. She is venerated as the Egyptian Nuit in the spiritual philosophy known as Thelema, developed by English occultist Aleister Crowley in the early 1900s. She is also sometimes associated with the Black Madonna, since the void of space is comparably hued. The Star Goddess is the cosmic void, the stellar womb from which creation arises. She is the uncreated one—the goddess who always was and always shall be.

In the Faery (or Feri) Tradition, the Stellar Goddess is sometimes called Mother Night, Sugmad, Sugmati, and the Great Infinite Darkness. Other Stellar Goddess figures around the world are Aya (Semetic Akkadian), Breksta (Baltic), Baachini (Navajo), and Nemissa (Algonkian). The Stellar Goddess also exists as the personification of the Pleiades constellation, called the Seven Sisters, for the seven maidens who became stars in Greek mythology. These seven stars are known as the Meamei to the Aborigines of Australia, while the Paiute people of North America call them Coyote’s Daughters.

Working with the Stellar Goddess can yield transformational magick. Generally, stars represent hope; they are wishes waiting to be fulfilled. The Stellar Goddess is our most ancient ancestor, the cosmic Mother. Connecting to her opens the door to personal gnosis and deep-seated healing.

The most famous of gems ascribed to the Stellar Goddess is lapis lazuli; the body of the goddess Nuit was depicted as resembling its pattern of golden flecks amid a dark blue background. Lemurian jade, consisting of pyrite flecks against a backdrop of black jade, is also a perfect representation of the Star Goddess. Other stellar stones include moldavite and other tektites, meteorites, and gemstones with asterism, such as star sapphire, star ruby, and exceptional examples of rose quartz, moon quartz, garnet, and black diopside. Nebula stone is also deeply attuned to this aspect of the Great Goddess.

Underworld Goddess and Dark Goddess

I’ve grouped these two archetypes together, since the distinctions between them are not clear-cut. The Dark Goddess is the complementary pole of the bright aspect of the Great Goddess; they are at once opposite and conjoined. To know one, we must know the other. Janet and Scott Farrar, authors of eight books on witchcraft, write, “The Dark Goddess . . . represents the mysteries of the Unconscious, both personal and collective, the indirect awareness of intuition, of instinctive attunement to the environment and the processes of fertility, of the useful warning stimulus of pain or discomfort, of the instinctive urge to achieve and create the merging of identities in sexual union.”4

The Dark Goddess archetype rules over fear, darkness, death, and night, all of which are a natural part of life. By embracing these often-repressed aspects of life we can mend the fragmented parts of our psyches, the bits that are battered by the throes of life and death. The Dark Goddess is no less loving than any other goddess, but her love is severe; she sets boundaries and teaches us our deepest lessons. Sometimes she is called “Underworld Queen,” as with the Greek goddess Persephone/Kore (or Proserpina to the Romans). Other times she is the ruler of nonhuman realms like that of the fairy folk. The Underworld Goddess is the chthonic aspect of the Earth Mother who represents the unseen and unknown realms. Her role can overlap with that of the Fierce Goddess, who oversees war and strife, or with that of the deathly Crone and the Mistress of Magick. She is the complement to each face of the Great Goddess.

Dark Goddess figures can be the Maiden, the Mother, or the Crone. We know her as Persephone and Hekate, as the Cailleach and the Morrigan. She is the Egyptian goddess Nephthys, associated with the underworld and with death and decay. She is also Kali of India, at once the great creator and destroyer. Other forms of the Dark Goddess and the Underworld Goddess are Hel, Ereshkigal, Eris, Sedna, Blodeuwedd, Scathach, and sometimes Epona and Rhiannon. Many strains of traditional witchcraft honor her as Lilith, the first wife of Adam.

The Dark Goddess and the Underworld Goddess can be invoked for magick related to transformation. She is the healer of our deepest wounds, granting us the reserves of power and strength needed for our most powerful magick. These two closely related archetypes can also work with us for defensive magick such as protection, banishing, and bindings. They often rule the theme of divination and communication with spirits.

Crystals that relate to this aspect of the Great Goddess include obsidian, jet, carnelian, and holey stones. Garnet represents the meal of pomegranates that bound Persephone to the underworld, thus it is a potent ally in working with her and her fellow queens of the underworld. Ammonite depicts the spiraling force of the chthonic mother of serpents, the dark aspect of the Earth Mother. Black moonstone represents the waning and dark of the moon, which represent these archetypes in the lunar cycle. Red coral, kunzite, and turquoise are also associated with the Underworld Queen.

Goddess of Love

Aphrodite, foam-born maiden with golden tresses, probably comes to mind when you envision the Goddess of Love. This archetypal role of the Goddess is often associated with the Maiden, whose independence in love and romance inspires us to pursue beauty and seduction. However, the Goddess of Love is also connected to the archetypal Mother, as she celebrates fertility, like that of the earth.

The Goddess of Love is represented by the symbols of love, beauty, and romance. She is the bright star that appears in the morning and the evening, the planet Venus, whose effulgent beauty adorns the sky like a gemstone in a celestial crown. Other goddesses representing this archetype include Freyja and Frigg, Hathor, Hera, Gwenhwyfar, Parvati, and Var. The goddesses Isis, Inanna, Ishtar, and Astarte are also conjoined in the Goddess of Love archetype at times. In the pantheon of the African diaspora, Erzulie and Oshún wear the guise of the Goddess of Love.

Invoke the Goddess of Love for drawing love and beauty into your life. She can help you find your inner beauty, which boosts self-confidence. She also rules fertility, which we can use for both biological fertility and for a fertile imagination.

Loving gemstones such as rose quartz, ruby, and jade are employed under her auspices. Minerals rich in copper such as chrysocolla, azuritemalachite, cuprite, dioptase, malachite, and metallic copper are excellent tools for working with the Goddess of Love in spell and ritual. Amber, sacred to Freyja, has long been used for love-drawing magick too. Try using rutilated quartz (nicknamed “hair of Venus”) and vanadinite (named for titles by which Freyja is known), as well as pearls, pink tourmaline, and emerald for connecting to the Goddess of Love.

Sacred Harlot

A minor archetype that in many ways overlaps with the Goddess of Love and other goddesses is the Sacred Harlot. She represents unbridled sexuality; her very body is her instrument of magick. In the poem “The Charge of the Goddess” by the English witch Doreen Valiente (1922–1999), there is a line that reads “Let my worship be within the heart that rejoiceth, for behold: all acts of love and pleasure are my rituals.”5 This is the heart of the Sacred Harlot.

Priestesses and female worshippers of the Great Goddess in antiquity were sometimes described as “temple whores” or simply as “whores” and “prostitutes” by later Christian theologians and writers. Though this terminology is derogatory, meant to steer the people away from their pagan worship, it offers a patriarchal perspective on the sexual and social autonomy that women enjoyed at a previous time during the reign of the Great Goddess. By reclaiming the Sacred Harlot as embodied by the lustful face of the Goddess, we can once again elevate the status of women in our world. By permitting the Goddess to wear her sexuality without judgment, we empower women today to reclaim their sexual identity and the power that comes with it, thereby removing the shackles of shame and objectification that women have worn for too long.

The Sacred Harlot is revered in the spiritual practices of Thelema, where she is known as Babalon. Babalon is called “the Red Goddess” and “the Scarlet Woman,” and she is often regarded as Inanna-Ishtar or as the secret identity of the goddess Nuit. Her symbolism is a juxtaposition of the sacred and the profane; she mixes life and death, lust and love, light and dark. Lilith, first wife of Adam in early Hebrew lore, is related to an earlier Mesopotamian goddess who was turned into a demon by later religious writers, who asserted that Lilith was cast out because she refused to be sexually submissive to Adam. The Sacred Harlot offers her flesh as a conjugal communion. It is probably for this reason that she was vilified by the rabbinic tradition. To the Aztec, the Sacred Harlot is Tlazolteotl, and the Hindu people know her as Rati. Additionally, ancient goddesses whose female supplicants were called “temple prostitutes” include Asherah, Inanna, Astarte/Ashtoreth, Anath, Aphrodite, Cybele, and others; those women who devoted themselves to this aspect of the Great Goddess were themselves embodiments of the Sacred Harlot.

The Sacred Harlot can be invoked for rites of love, lust, beauty, pleasure, and power. Her sexuality is alchemical in that she transmutes what she touches.

Of all the crystals that attune to the archetype of the Sacred Harlot, the scarlet temple Lemurian seed crystal (also called strawberry Lemurian seed crystal) represents her most fully. Other crystals that can be used to connect with her include alabaster, orange calcite, copper, pearl, and vanadinite. Carnelian, with all its carnal symbolism, is used for magick that falls in her domain, and creedite is sexually empowering and liberating, thus connecting it with the Sacred Harlot too.

The Muse

The Muse is the archetypal goddess of the arts, crafts, learning, and wisdom. She is the light of inspiration for poets and writers as well as the vision that sculptors, painters, and other visual artists pursue. She can be the patron of wisdom and learning, as this too requires inspiration. The Muse can refer to the classical muses of Greco-Roman mythology, as well as to goddesses such as Athena, Minerva, Ariadne, Saraswati, Aphrodite, and Benzaiten. In many cases the goddess-as-muse is an aspect of the Maiden aspect of the Triple Goddess. Call on her for help with any creative endeavor, as well as in the pursuit of truth and beauty.

Crystals and gemstones appropriate for connecting to the Muse include alabaster and marble (both of which are artistic media for sculptors), carnelian (to activate your creativity), fluorite (for the self-discipline and follow-through to carry out your artistic or intellectual pursuits), and kyanite (to help you see the bigger picture). Chrysocolla is one of my favorite Muse stones, as it helps you pursue beauty and express it unflinchingly.

The Fates

The concepts of destiny, time, and karma are often embodied in the form of the Goddess known as the Fates and the Wyrd Sisters. Though the Divine Masculine principle in Western magickal traditions is viewed as the dying god or sacrificial king, the Great Goddess is eternal. For this reason she is the embodiment of time and fate.

The Fates are frequently depicted as a Triple Goddess, though some traditions personify fate and time as singular rather than plural. To the Nordic people the personification of the Fates were the Norns, or the Wyrd Sisters: Urdhr, Verdhandi, and Skuld. The Greeks knew them as the Moirai (or Fates): Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos. Their Roman equivalents are the Parcae: Nona, Decima, and Morta. They are believed to spin, measure, and cut the thread of each person’s life. Analogous figures in the mythology of other cultures include the Bulgarian Orisnitsi, the Nordic Valkyries, the Celtic Matrones, and the Lithuanian goddess Laime. In northern India, the Goddess of Fate is Behmata. To the pre-Islamic people of the Arabian peninsula, fate was personified as Manat. The Spider Woman of some Native American storytellers is also known as Spider Old Woman and Spider Grandmother, the spinner of fate.

Work with the Fates to heal on the causal, or karmic, level. They can offer you the tools and lessons needed to break persistent cycles in your life and overcome obstacles that have held you back for great periods of time. They can also be contacted to support divination and prophecy, as well as to provide healing during times of grief and loss.

Crystals connected to the Fates include gray and black moonstone, fossils, obsidian, and amazonite. Faden quartz, named for its threadlike inclusions, is strongly linked to the imagery of the thread of life that is spun, measured, and snipped by the Fates; it is one of my favorite stones for connecting with this archetype.

SYMBOLS OF THE GODDESS

In addition to working with the crystals listed in the previous entries on archetypes, symbols are another powerful way to connect with the many facets of the Great Goddess. Symbols serve as an archetypal language, one that speaks to the subconscious and superconscious. Cultures around the world have developed their own tradition of symbolic imagery, and many of these symbols overlap.

The symbolism built around the Divine Feminine tends toward figures built from circles, curves, and spirals. These representations build on the primal symbols of womanhood and the very essence of the feminine mysteries. They are inspired by the fertile curve of breast and belly. They are sometimes tokens of the birth canal, the portal of life. Natural features that echo these forms are considered sacred to the Divine Mother—images like the changing phases of the moon and the curve of holy hills and the opening of the sacred cave. Birds, beasts, trees, and flowers also lend themselves to the language of the Goddess.

An overview of goddess-oriented symbols follows. These symbols can be incorporated into meditation, ritual, and spellcraft. You may inscribe them on candles or on parchment. They are the perfect patterns for making crystal grids, serving as templates for the arrangement of stones, whether for healing, meditation, or spellcraft.

Yonic Figures

Symbols of the yoni are among the earliest representations of the Divine Feminine, for they represent the female reproductive organs. The downturned triangle representing the pubic delta is connected to the alchemical symbols for water and earth. Chevron patterns adorn ancient vessels and statues that depict the Great Goddess of the Stone Age; these chevrons may represent the breasts and pubic triangle, though some may symbolize a bird goddess once widely worshipped.6 Eggs are also vaguely yonic in shape, and they too represent the Goddess’s power to create life.

Chevron, triangle, lozenge, yoni, and vesica piscis

These symbols are often ascribed to rites of fertility, creativity, and empowerment. They are most closely related to the archetypes of the Mother from the Triple Goddess (as well as all mother figures among the archetypes of the Divine Feminine), the Goddess of Love, and the Sacred Harlot.

The Spiral

The spiral is easily one of the most universal and recognizable symbols of the Goddess. Spirals represent the sacred labyrinth wherein the mysteries of initiation might be experienced. Spirals are associated with the serpent, the chthonic or telluric aspect of the Earth Mother and a symbol of fertility and sexuality. Archaeologist Marija Gimbutas posits that spirals in ancient art were symbols of the Goddess because they represent the life force, such as in the uncoiling of new plant growth and the ever-changing cycles of the moon.7

For many, the spiral is a symbol of the soul’s path of reincarnation representing the never-ending journey of birth, death, and rebirth. Spirals are thus connected to the Fates. Practitioners of most branches of the magickal arts associate clockwise-turning spirals with drawing an influence inward and counterclockwise spirals with banishing or removing a particular influence. However, this language is not universal, as some cultures, like the people of Japan, use these directions in reverse.

A variety of spirals

The Circle

Circles mirror the shape of the sun, moon, and our planet Earth. Circular and spherical objects like dishes, bowls, mirrors, and cauldrons are typically considered sacred to the Divine Feminine. Like the Great Goddess herself, the circle has no beginning or end; it is eternal and holds us safely in her embrace. Circles may be protective, and circles of crystals or stones can be used to delineate sacred space.

Circle

The Moon

The moon in its various phases has long been connected to the Divine Feminine. Crescent moons are often connected to the upturned shape of a bull’s horns; both have long been considered symbols of fertility. The connection between such figures and the Divine Feminine lies in the similarity between the shape of the female reproductive system (uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes) and that of the outline of the bull’s cranium.8 Since antiquity, crescent-shaped axes, knives, and other ritual implements have been used to symbolize the Divine Feminine.

Symbols of the Divine Feminine as seen in the shapes of the moon

Crescent shapes and triple-moon figures are the most common representations of the Goddess today. They are typically used for lunar magick and for connecting to other aspects of the Moon Goddess.

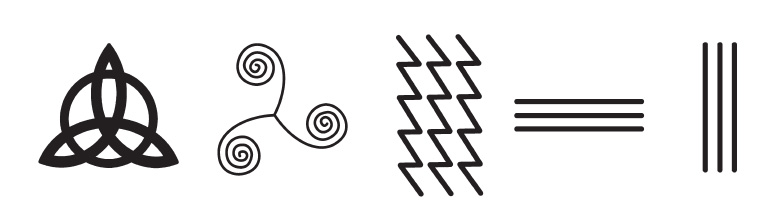

Triple Figures

Triple knots, overlapping circles, and triple spirals are but some of the many triune formations used to represent the threefold aspects of Maiden, Mother, and Crone. Many of these symbols are also considered protective. They are often used as general symbols of the Divine Feminine by practitioners today. Ancient sculptures depicting the Great Goddess often exhibit triple lines or dashes; they are painted on her eyes, mouth, and body. This symbol depicts the multiple streams of sustenance that the Great Mother provides.9

Left to right: triple knot, triskelion, and three tri-line symbols

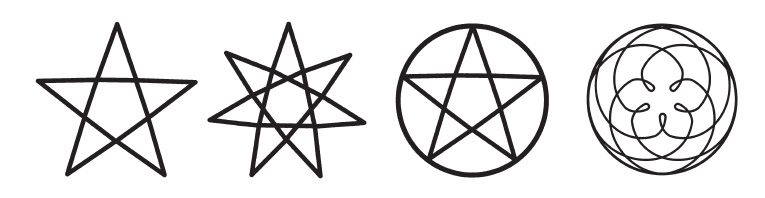

Pentagrams and Stars

Various stellar symbols correspond to many aspects of the Divine Feminine. The five-pointed pentacle, especially when enclosed by a circle, represents the four material elements of the Western mystery traditions (earth, air, fire, and water), crowned by the immaterial quintessence, the spiritual element variously called ether, space, void, and spirit. In many traditions the pentacle or a tile, paten, or dish inscribed with a pentagram is the symbol for the element of earth on the altar, earth being a feminine element.

Pentagram, septagram, pentacle, and transit of Venus

The five-pointed star is related to the pattern the planet Venus makes as it traverses the sky. Since Venus is intimately linked to the Goddess, such a fivefold figure may have its origin as a symbol of the Goddess on this planet’s path. Other symbols modeled on the star can help you connect to the Stellar Goddess.

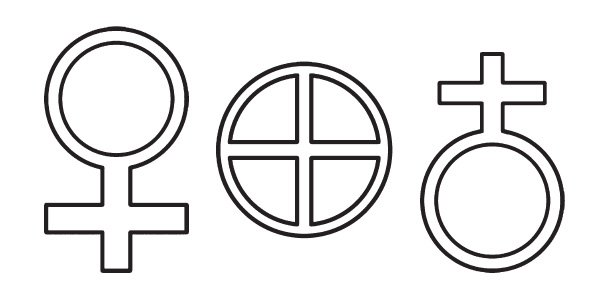

Planetary Symbols

The astrological symbol for Venus has been used to denote the female gender since the 1750s when the Swedish scientist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) used the symbols for Venus and Mars to refer to the sex of plants. It is used by both spiritual and secular schools to represent the nature of femininity, and thus it carries a strong connection to the Divine Feminine. Originally meant to resemble a necklace, this symbol has been likened to Venus’s mirror; it was also used by alchemists and chemists to indicate the element copper. The symbol for Venus may be used for all energies under this planet’s domain; it relates to the archetypes of the Goddess of Love, the Sacred Harlot, and the Muse.

Left to right: the symbols for Venus (the first figure) and Earth (the second and third figures)

The symbols for Earth as shown above were used by astrologers only after heliocentrism was established scientifically by Copernicus in the sixteenth century. The circle with the cross inside represents the four cardinal directions, while the circle mounted by the cross is taken from the alchemical symbol for antimony. These figures may be used for magick related to the element of earth, such as for grounding, healing, prosperity, and protection.

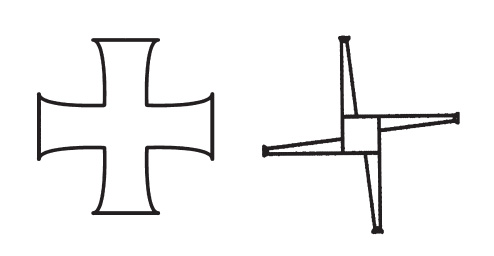

The Cross

Crosses are related to the four cardinal directions, the four elements, and the four seasons. The cross formed by the four points of the compass is often connected to the Medicine Wheel and to the element of earth; thus it may be used as a representation of the Earth Mother. Equalarmed crosses, including Saint Brigid’s cross, are often connected to solar symbolism. Use crosses to invoke the sun for centering and protection.

Left to right: solar cross and Saint Brigid’s cross

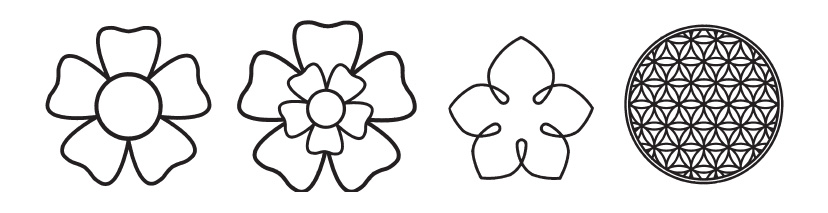

The Flower

Floral patterns depict the blooming, springtide aspect of Mother Nature. The five-petaled rose is a symbol of the Divine Feminine in Western mystery traditions, and it can be used to invoke and honor the Goddess. The Flower of Life, the last figure shown in the illustration, is a fundamental symbol in the study of sacred geometry. It is the creation pattern that leads us into and out of physical existence, and thus represents the Goddess as the womb from which all form is birthed and the cosmic void to which we all return. It is composed of overlapping circles, another sacred symbol of the Goddess. The Flower of Life is a popular template for making crystal grids. Flowers can be used as offerings on the altar, and floral symbols work in many of the same ways as the star symbols described earlier.

Flower imagery, including the Flower of Life (far right)