![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cancer recurrence refers to the return of cancer. Most women who are treated for early stage breast cancer remain disease-free, but some do experience a recurrence. When a cancer recurs, it means that some cancer cells remained in the body after cancer treatment and these cells have begun to grow.

Recurrence may occur weeks, months, years or even decades after an initial diagnosis. Sometimes, the cancer returns in the same location as the original tumor. Other times, it recurs in a different location. For example, a few cells from a breast tumor may have spread to bone by way of the bloodstream. These cells weren’t eliminated during treatment, and eventually they multiplied to a size that could be detected.

For many women, dealing with a cancer recurrence is more difficult than dealing with an initial diagnosis. Recurrence is often a breast cancer survivor’s greatest fear. If your cancer does come back, you may feel as if you’ve lost the battle against the disease and that all your efforts were in vain. But this is not necessarily the case. The treatments you received may have actually delayed the cancer recurrence, giving you additional time you might not have had otherwise.

Although it’s true that most breast cancer recurrences aren’t curable, for some, there is potential for a cure, depending on where the recurrence is located. Even if a cure isn’t possible, treatments can help maintain your quality of life and control the cancer, sometimes for many years.

Breast cancer recurrence is generally categorized by location. It can be local, regional, distant or a combination of these.

Local recurrence

A local recurrence means the cancer redevelops in the same spot, or vicinity, as the primary tumor. For example, if you had a lumpectomy in your right breast and the cancer recurs in that same breast, that’s a local recurrence. This type of local recurrence is called an in-breast recurrence.

It’s possible that a new primary tumor may develop in the breast of a woman who has had a lumpectomy. A new primary tumor isn’t the same as a recurrent tumor, although the two can be difficult to distinguish. A general rule of thumb is that if cancer is found in the same breast 10 or more years after the first tumor, it’s considered a new primary tumor. Recurrent cancer tends to develop sooner — usually less than five years from the initial diagnosis. In some cases, a new primary tumor may develop in the opposite breast. This isn’t a recurrence either. Rather, it’s treated as a new primary breast cancer.

If you’ve had a breast removed (mastectomy) and cancer appears in your chest wall near where the breast had been, that also is a local recurrence.

Regional recurrence

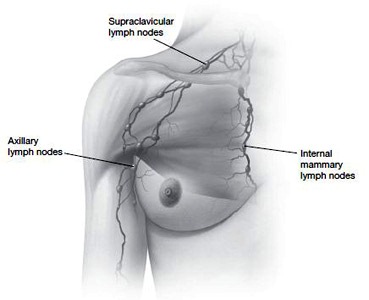

A regional recurrence means that cancer cells have broken away from the original tumor site and they are appearing in nearby lymph nodes, such as those under your arm, near your breastbone or above your collarbone.

Local and regional recurrences may occur simultaneously. The two are often lumped together and termed local-regional recurrences. In this situation, there isn’t any proof that the cancer has spread to more distant parts of the body.

Metastatic recurrence

A metastatic recurrence is when the original cancer cells have managed to travel to other organs or tissues in your body besides your breast, chest area or nearby lymph nodes. This type of cancer is called metastatic because the cancer has been identified in places away from the original tumor site. Other terms that are sometimes used are systemic or distant recurrence, because the cancer is now affecting more than one part of your body — more than just your breast and the area around it.

Most often breast cancer cells spread to bone. Other sites of metastases include the lungs and liver. Less often, the cancer spreads to the brain or other areas of the central nervous system.

Although it seems logical that a local recurrence would come first, then a regional recurrence and then a distant one, it isn’t always this orderly. Many times a distant recurrence will occur without a local or regional recurrence.

The manner in which cancer spreads to your lymph nodes and other parts of your body is a long and complicated process. Most cancer cells don’t make the journey, but some of the ones that do are hardy enough to establish themselves in other tissues and survive there.

Normally, the cells that make up the organs and tissues of your body, including your breasts, are held in place by a substance called an extracellular matrix. For cancer cells to travel outside of your breast, they must first break through this extracellular matrix. They appear to do this by breaking down the matrix with enzymes or by altering the adhesiveness of their own cell surface.

Once they’re free of this matrix, cancer cells can invade nearby tissues or travel through the lymphatic system or bloodstream to other more distant organs and tissues. Your lymphatic system is a network of channels throughout your body, similar to your circulatory system, but instead of carrying blood, it carries lymphatic fluid and immune cells.

With breast cancer, cancerous (malignant) cells that have broken free of the original tumor may be swept along with the lymphatic fluid that drains from your breast tissue and eventually may end up in your axillary lymph nodes — bean-shaped structures of lymph tissue located under your arm. Some of the cancer cells may be destroyed in the lymph nodes, which are full of scavenging white blood cells that ingest and destroy foreign substances. But some cancer cells may evade immune cells and survive and multiply in the lymph nodes, or they may travel on within the lymph system.

To get into your bloodstream, cancer cells may burrow their way through a blood vessel wall (see the color illustration in the Visual Guide). Once the cells are in the bloodstream, they’re swept along with the flow of blood and may be carried to parts of your body far from your breast. Like your lymphatic system, however, your bloodstream is also full of immune cells capable of destroying cancer cells that make their way in. Still, some cancer cells may survive the ride. These cells can become lodged in the smaller branches of your blood vessel network. From there, they burrow their way out of the blood vessel into nearby tissue — such as bone, lung or liver — where they may survive and grow in a different environment from which they originated.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Breast cancer cells have a different makeup from bone, lung or liver cancer cells. They evolve differently, progress differently and respond differently to various therapies. When breast cancer cells spread to another part of your body — such as your bones, lungs or liver — they’re still breast cancer cells, but they’re growing in a different area. Breast cancer cells that are found in your bones don’t become bone cancer. You still have breast cancer, only now it’s called metastatic breast cancer in your bones.

One doctor uses the following analogy to explain this concept: If dandelions are growing in the yard and they go to seed, and the wind spreads this seed to the rose garden, allowing the dandelions to grow in the rose garden, these flowers aren’t called roses. They’re dandelions that have spread to the rose garden. In the same manner, if breast cancer cells spread within the body and start growing in the bone, they don’t become bone cancer, but breast cancer spread to bone.

This is important because breast, bone, lung and liver cancers behave differently and are treated differently. For example, lung cancer cells aren’t affected by estrogen in the way that breast cancer cells are. Therefore, lung cancer wouldn’t respond to estrogen-related drugs such as tamoxifen, but breast cancer cells in your lungs may.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Breast cancer can recur in your remaining breast tissue after a lumpectomy and radiation or in your chest wall tissue after a mastectomy. There are some differences between the two, so we’ll discuss each separately. Some general factors, though, that might increase your risk of these types of local recurrences include:

Some factors that may be in your favor if you have a local recurrence, regardless of your initial treatment, include:

Characteristics such as these are called prognostic factors, which can help predict disease outcome. Keep in mind, though, that these are generalizations about a complex disease, and your individual outcome isn’t based solely on such factors. Prognostic factors are mentioned throughout this chapter, but remember they serve only to give you a general picture. Nobody can know absolutely what will happen in your future.

Recurrence after lumpectomy

The risk of a local recurrence after undergoing a lumpectomy and radiation for stage I or II breast cancer is very low. When a recurrence does happen, it’s often an isolated local recurrence, meaning the recurrence isn’t widespread throughout the breast and there isn’t evidence the cancer has spread (metastasized) to distant locations.

Among women whose initial cancer was invasive and who experience an in-breast recurrence, in most cases the recurrent cancer is also invasive. In a small percentage of cases, the recurrent cancer is noninvasive (carcinoma in situ). Among women who initially had ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and who experience an in-breast recurrence, the recurrent cancer is invasive in about 50 percent of cases.

Signs and symptoms

About one-third of in-breast recurrences are detected by mammography before they can be felt. Another third are detected by self- or clinical examination and another third by a combination of the two.

The signs of an in-breast recurrence are generally the same as those of a new primary breast cancer, such as an unusual lump or a new change in your breast skin. But cancer can be a bit subtle the second time around, and sometimes it may be confused with a noncancerous (benign) abnormality. For one thing, surgery can produce changes in your breast, including mass-like areas of scar tissue, lumps of fatty tissue (fat necrosis) and scar tissue around the stitches used to close the incision (suture granulomas). Radiation can also cause scarring and increase decay of fatty tissue, which can make detection of a recurrence more difficult.

Often, breast changes that occur soon after treatment — for instance, within the first year — are benign, and often a result of treatment. However, it’s still important to point out the change to your doctor so that it can be monitored.

Occasionally, some women develop a breast infection (mastitis), which is characterized by inflammation, swelling and redness. Mastitis is easily treated with antibiotics, but your doctor will want to make sure that it’s not inflammatory breast cancer, a type of breast cancer that involves the skin and has features similar to mastitis.

So what should you watch out for? In general, report to your doctor any changes you notice in your breast, if only for your own peace of mind. Be particularly aware of these signs and symptoms:

If you notice any of these signs and symptoms, tell your doctor so that they can be evaluated further.

Tests

If you and your doctor suspect an in-breast recurrence because of results of a mammogram or physical examination, your doctor may use another imaging test, such as ultrasound, magnetic resonance image (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or a combination of these, to try to determine whether the suspicious finding is benign or malignant.

You’ll likely need a biopsy to confirm the presence or absence of cancer. Because the hormone receptor status of your cancer may change with a recurrence — the cells that survive may be a subpopulation of the original tumor — if cancer is found, the biopsy sample may again be tested for the presence of estrogen and progesterone receptors. The specimen may also be tested for signs of overproduction of the HER2 protein. Both the hormone receptor status and HER2 status are important in determining what types of therapy would be appropriate to treat the recurrent cancer.

Because some women who develop an in-breast recurrence also have distant metastases, other tests will likely be done to determine if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body. These tests may include a chest X-ray and other imaging tests, such as a computerized tomography (CT) scan, bone scan, PET scan or MRI. In addition, a complete blood count and liver function tests, as well as other blood tests may be performed.

Treatment

Treatment for an in-breast recurrence that occurs after a lumpectomy may include surgery, radiation therapy or drug therapy.

Surgery

Assuming there’s no evidence the cancer has spread to other locations, an in-breast recurrence is usually treated with a mastectomy. In some cases, a lumpectomy may be done, but using a lumpectomy to treat this type of recurrence is controversial. A lumpectomy carries a higher risk of yet another recurrence that may be more serious.

Because a local breast recurrence may be accompanied by hidden cancer in nearby lymph nodes, your doctor may remove some or all of the lymph nodes under your arm (axillary dissection) during surgery if they weren’t removed during your initial treatment.

Radiation therapy

If you haven’t had any previous radiation, your doctor will likely recommend it now. However, most women who undergo lumpectomy for their initial cancer also receive radiation. So, a second course of radiation usually isn’t be an option.

Not much data exist on the use of repeat radiation in women who received radiation to treat their original tumors. Plus, receiving additional doses of radiation may increase your risk of radiation-related side effects.

Drug therapy

If an in-breast recurrence is so extensive that surgery isn’t an option, your doctor may recommend chemotherapy, hormone therapy or both to treat the cancer. Most local recurrences, however, can be treated with surgery.

A decision to use chemotherapy, hormone therapy or both depends on a number of factors, including whether you received either to treat your initial cancer, and what type of treatment you had. Other important factors include your menopausal status, how long it has been since your initial diagnosis (your disease-free interval), details regarding your tumor, such as its hormone receptor status and HER2 status, and whether you have other health problems.

Prognosis

An in-breast recurrence is a sign the disease is still active, and it puts you at an increased risk of other recurrences in distant sites. The risk of metastisis after an in-breast recurrence varies according to a woman’s lymph node status at her original diagnosis. Women who were node-positive have a higher risk of later metastisis than women who were node-negative. Other factors that may predict outcome include:

Recurrence after mastectomy

Among women who have a mastectomy to treat breast cancer, about 5 to 10 percent experience a cancer recurrence in their chest wall tissue, either alone or in combination with other recurrences. Cancer recurrence on the chest wall is more likely in women whose original breast cancer had spread to lymph nodes. A local chest wall recurrence tends to occur within 10 years of initial treatment, but some local recurrences have been reported 15, 25 and even 50 years after a mastectomy.

In about two-thirds of the women who experience a chest wall recurrence after mastectomy, at the time the recurrence is diagnosed there are no indications that the cancer has also spread to distant locations. In the other third, there’s evidence the cancer has spread to other areas of the body.

Signs and symptoms

A local recurrence after a mastectomy usually appears as a painless nodule in or under your chest wall skin. It most often develops in or near the mastectomy scar. About half the local chest wall recurrences appear as a solitary nodule, while the rest show up as multiple nodules. Occasionally, a chest wall recurrence may appear as a red, often itchy skin rash.

Among women who’ve had tissue flap breast reconstruction, a recurrence may develop in the skin near the stitches or in the remaining chest wall skin, but a recurrence in the flap itself is rare. Recurrences isolated to the chest wall muscle also are rare. Benign lumps and fat necrosis, another benign condition, are fairly common with tissue flap reconstruction. If a lump occurs, a doctor may want to do a biopsy to make sure the diagnosis is correct.

Tests

Almost all chest wall recurrences after mastectomy are detected by physical examination. In breast reconstruction using a tissue flap, mammography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help distinguish between a cancerous mass and a noncancerous mass. A biopsy can confirm the presence of cancer. The biopsy specimen will likely be tested for estrogen and progesterone receptor status and HER2 status.

Again, because of the possibility of distant recurrence, your doctor will likely request other tests also, including a chest X-ray and other imaging tests, such as a CT scan, bone scan, PET scan or MRI. A complete blood count and liver function tests, as well as other blood tests also may be performed.

Treatment

A chest wall recurrence after a mastectomy is typically treated with surgery, if possible, as well as radiation and medication — chemotherapy, hormone therapy or both.

Surgery

If the recurrent cancer is a solitary nodule that can be fairly easily removed, surgery may be done. If the disease is more extensive, surgery usually isn’t recommended.

Radiation therapy

If you haven’t received radiation before, your doctor will likely recommend it now. Radiation therapy after a mastectomy may provide the most effective local treatment for a chest wall recurrence.

Usually, the whole chest wall area is treated. This may include the area around your collarbone to reach nearby lymph nodes, which are at increased risk of recurrence. Sometimes — especially if some cancer still remains in the chest wall after surgery — an additional boost of radiation is given directly to the area of recurrence.

Chemotherapy and hormone therapy

Medication (systemic therapy) may be recommended after surgery and radiation to reduce the risk of another local recurrence or a metastatic recurrence. There aren’t any good studies to direct doctors regarding the use of systemic therapy in preventing additional recurrences, but some studies suggest it can be helpful.

Prognosis

Compared with an in-breast recurrence after lumpectomy, a chest wall recurrence after mastectomy carries a considerably higher risk of eventual spread of the cancer to distant sites. Nonetheless, certain factors may indicate a better prognosis:

After a mastectomy or lumpectomy and radiation, it’s possible for cancer to recur in the lymph nodes near the breast that was treated. This is known as a regional recurrence. A regional recurrence can occur by itself, but often it occurs simultaneously with a local recurrence and is referred to as a local-regional recurrence.

Types

Regional breast cancer recurrences are generally divided into one of three categories:

Signs and symptoms

The first sign of a regional recurrence is usually a swelling or lump in the affected lymph nodes, such as those under your arm, in the groove above your collarbone or in the area around your breastbone. Because your internal mammary nodes are located deep within your chest, a small recurrence in this area is more difficult to detect.

Regional recurrences aren’t always accompanied by signs or symptoms. One study found that signs and symptoms occurred in only 30 percent of women with an isolated regional recurrence.

Signs and symptoms that may indicate a regional recurrence include:

If you experience any of these, tell your doctor so that they can be evaluated.

Tests

A regional recurrence may be detected when your doctor asks you about any new symptoms or while doing a physical examination.

A CT scan, an MRI or a PET scan may be helpful in evaluating a suspected recurrence in regional lymph nodes. A biopsy may be performed.

Because a regional breast cancer recurrence carries a high risk of distant recurrence, your doctor will likely have you undergo other tests to check for spread of cancer to other areas of your body.

Treatment

If it’s possible, surgery may be the best option for removing the tumor and controlling the cancer. In some cases, radiation therapy may be used after surgery to further destroy any cancer cells. If surgery isn’t feasible, radiation therapy may be used as the primary form of treatment. Other lymph node areas may also be radiated to try to prevent further recurrence.

Because of significant risk of distant recurrence, chemotherapy or hormone therapy may be recommended after surgery, radiation or both to prevent recurrence of the cancer at other sites.

Prognosis

With a regional recurrence, your prognosis generally depends on where the recurrence is located, whether it’s isolated, how long it was from the time you were first diagnosed until the recurrence, and certain characteristics of the cancer.

Most women with regional breast cancer recurrences aren’t cured. If the cancer has spread to regional lymph nodes, it likely has spread to other parts of the body, too. However, even when a cure isn’t possible, with appropriate therapy it’s still possible to live for years.

When breast cancer cells reappear in parts of your body other than your breast or nearby lymph nodes, the cancer is considered a distant (metastatic) recurrence. Breast cancer most commonly spreads to the bones, lungs and liver. Other sites include the brain, skin, lymph nodes, abdomen and ovaries.

Signs and symptoms

Breast cancer that has spread to other areas of the body usually is detected by way of signs and symptoms.

Breast cancer that has spread to bone may be signaled by bone pain. Breast cancer that has spread to the lungs may produce the following signs and symptoms:

Liver metastasis may be signaled by:

Brain metastasis may be signaled by:

Biopsy

A diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer needs to be made with as much certainty as possible. Often, this involves a biopsy of a tumor at a distant site. The tissue collected is tested for certain characteristics, such as estrogen and progesterone receptors and HER2 receptors.

In some situations, though, a biopsy is either dangerous or unnecessary. For example, if you have a history of breast cancer and multiple new masses (tumors) occur in your bones or lungs and there’s no other explanation for these masses, a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer can be made with reasonable certainty without the need for a surgical biopsy. However, because breast cancer treatment is dependent upon the characteristics of the tumor cells, sometimes a biopsy is done so that your treatment can be tailored to the characteristics of your cancer.

Other tests

If your doctor suspects your cancer has spread to other areas of your body, he or she may use a number of tests to confirm the presence or absence of cancer cells in these locations.

Laboratory tests

Among women with metastatic breast cancer, laboratory tests may include:

In women who haven’t experienced any signs or symptoms of a distant recurrence, blood tumor marker tests generally aren’t adequate and specific enough to detect cancer. But they may help confirm a cancer recurrence in women with symptoms.

Imaging tests

Your doctor may use one or more of the following tests to check your lungs, liver, bones and abdomen for any unusual masses or structural abnormalities:

Prognosis and treatment

Because metastatic cancer is characterized by the spread of cancer cells throughout the body, systemic therapy — therapy that treats the whole body — is generally the recommended treatment. This may involve use of chemotherapy, hormone therapy or both. Radiation also may be used to relieve cancer-related symptoms, such as pain, in specific locations.

The main goal of treatment for an individual with a metastatic breast cancer recurrence is to have the woman do as well as possible for as long as possible. This concept may be better understood if it’s broken down into four parts. The goals of treatment are:

In general, metastatic breast cancer isn’t considered curable, but the prognosis for individual women can vary widely.

Treatment and prognosis of metastatic breast cancer is discussed in detail in the next chapter.