4

BESTIALITY AND BESTIAL RAPE

IN GREEK MYTH1

J.E. Robson

There has been no literature on the subject of bestiality in Greek myth, and this is a gap which I intend to fill with the present paper. Good work has appeared both on the subject of Metamorphosis in Greek Myth, the title of a recent book by Paul Forbes-Irving, and on the evergreen subject of sex in myth, such as chapters in Angelika Dierichs’ Erotik in der Kunst Griechenlands and Amy Richlin (ed.) Pornography and Representation in Greece and Rome. However, no scholar has yet synthesized these two topics to write on mythical bestiality or bestial rape.

My approach to myth will be similar to that of Forbes-Irving and Mary Lefkowitz, in that I mean to treat myths primarily as moral stories, which held both educational and entertainment value for the original audience.2 In the course of this paper, I shall attempt to arrive at conclusions on how myths of bestiality arose and why the myths continued to be retold by successive generations. In order to do this, I shall draw on material from Greek religion and ritual and from anthropological sources. I shall attempt to locate the patterns of these myths within the everyday experiences and expectations of not only Greek men, but Greek women also, my assumption being that whereas men played a disproportionately large role in the creation and reception of literature, both sexes were involved in the process of the relation of myths from generation to generation.3

The mythical material which forms the basis of the present discussion is detailed in the appendix. When bestiality occurs in myth it is only occasionally true bestiality–that is, between a human and a genuine animal. Myths tend rather to concern relations between a god and a young woman, at least one of whom has been metamorphosed into an animal. In addition to these, I shall include in my analysis those myths which concern sexual intercourse between two animals, when the protagonists are in fact a metamorphosed god and a metamorphosed young girl. As will become apparent, one of the aims of the present paper is to investigate both what the details and the underlying structures of these myths tell us as to their position within the mythical corpus and, further, their significance to the original audience.

The majority of ‘bestial’ myths involve the rape of a young girl by a god. In consequence, rape myths will form the central subject of discussion in this paper. Other myths on bestial themes will largely be treated with the purpose of placing the rape myths in a wider context.

A problem arises when we try to date the emergence of the myths under discussion. Many of our sources are Hellenistic or Roman, and so it is possible that some bestial myths are late literary inventions. For those few myths which are well documented in both archaic and classical sources, it would appear to be the rule, however, that their bestial versions receive their first telling in the latter era. For example, the first mention of Zeus having turned himself into a swan in order to rape Leda is made in Euripides. Only in post-Homeric versions of the myth of Ganymede is he abducted by an eagle. The nature of our sources renders it impossible, however, to ascertain with any degree of certainty when or where any one of these myths arose.

My paper has a sociological focus, and I do not see my approach as superior to that of, say, a scholar of Greek religion.4 My reading is but one possible approach to the mythical corpus, albeit one that unashamedly draws on the work of those who might privilege different aspects of these myths. In sections I to IV, I shall explore three points of departure for analysing these myths. In I, I look briefly at bestiality as sexual fantasy; in II, hunting myth and metaphor from other cultures, and in III and IV, Greek initiation ritual and religious ceremony. From there on, I shall try to unite these threads and examine more closely the aspects of Greek society to which I believe these myths relate.

I

However much we might not like to think so, bestiality still has some fascination for contemporary society as fantasy, as can be demonstrated by the existence of bestial pornography.5 There is evidence, too, for a similar interest in bestiality in Ancient Greece. There are numerous vase paintings, for instance, of satyrs having sex with deer,6 donkeys7 and even a sphinx.8 Satyrs are sexually transgressive by nature and so are often employed by vase painters to depict behaviour that is of marginal acceptability for humans.9 However, there also exist vases which show men having sex with deer10 and depictions of maenads being approached by various animals, such as ithyphallic donkeys.11 Depictions of myths of bestial rape are more common still,the subjects of Europa, Leda and Ganymede being the most popular. However, it is usually the abduction of these latter figures which is depicted rather than an act of sexual violence.12

According to the Kinsey report, about eight per cent of men had indulged in bestial sex in mid-twentieth-century America,13 that figure rising to fifty per cent in rural areas. Apart from this, evidence for a fascination with bestiality, and evidence for its practice, comes to us from other eras of European history too. Midas Dekkers documents some of the bestiality trials that took place in Europe between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries14–trials which often led to the public execution not only of the perpetrator, but also of the animal concerned. He also documents modern cases.15 At first sight, then, perhaps myths of bestiality have some connection with both sexual fantasy and even sexual practice.

II

Hunting myth from non-Greek cultures may also prove instructive as to how bestial myth comes into being. Some hunting ritual involves dressing up as the prey, donning the animal’s skin, and also worship of the animal. With these ingredients, the fluidity of mythical logic can allow animal, human and divine identities to merge.

One myth which very neatly demonstrates this merging comes from the Blackfoot Indians of Montana. The traditional hunting methods of the tribe involve luring the buffalo to jump over a cliff into an enclosure below.16 The myth begins as follows:

Once upon a time...the hunters, for some reason, could not induce the animals to the fall, and the people were starving. When driven toward the cliff the beasts would run nearly to the edge, but then, swerving to right or left, go down the sloping hills and cross the valley in safety. So the people were hungry, and their case was becoming dangerous.

And so it was that, one early morning, when a young woman went to get water and saw a herd of buffalo feeding on the prairie, right at the edge of the cliff above the fall, she cried out, ‘Oh! if only you will jump into the corral, I shall marry one of you.’

This was said in fun, of course; not seriously. Hence her wonder was great when she saw the animals begin to come jumping, tumbling, falling over the cliff. And then she was terrified, because a big bull with a single bound cleared the walls of the corral and approached her. ‘Come!’ he said, and he took her by the arm.

‘Oh no!’ she cried, pulling back.

‘But you said that if the buffalo would jump, you would marry one. See! The corral is filled.’ And without further ado he led her up over the cliff and out on to the prairie.17

The myth ends with the girl happily returned to her tribe, who through her gain a magic dance by which they might secure a permanent supply of buffalo. This dance entails the tribesmen dressing up as buffalo.

The practice of the hunter dressing up as his quarry is not peculiar to the Blackfoot Indians. A representation of a buffalo-dancer is also to be found at the Trois Frères caves in southern France, for example.18 Anthropological evidence from Australia also shows tribesmen dressing up as animals, wearing animal masks, standing on all fours and wearing horns.19 At the root of this, Burkert would suggest, is that in hunting man perceives himself as an animal.20 An important difference between the human and the animal hunter, however, is the former’s use of guile: in capturing his prey man employs technology in the shape of weapons.21

Also not peculiar to the Blackfoot Indians is the notion of a human virgin being bride to the quarry of the hunt. Burkert cites a Chukchi myth where a young girl is bride to a whale.22

In myths of bestial rape, a virgin is often assaulted by a god who has taken on animal form. Later I shall suggest that such details in bestial rape myths have a connection with hunting myths and practices.

III

A third strand that might be of interest when discussing myths of bestiality and bestial rape is that of Greek ritual and religious ceremony. In this section, I shall discuss male initiation ceremonies, in the belief that details from these rituals have become encoded in ‘bestial’ myths. The rituals are also instructive concerning Greek views on the status and role of adult men in Greek society. These views are important in understanding the significance of ‘bestial’ myths. Of particular interest for the present enquiry is the prominence of hunting in male initiation rituals.

Practices varied between city-states, but typically, when a boy was to come of age, he was taken out in a group into the ‘wilds’, an area loosely defined, but of great psychological importance.23 The wilds comprised that which was beyond the polis, an area which lay outside the control of civilization. Here, older men acting as officiators would have the boy perform various rituals involving hunting and crossdressing. The idea of these rituals was to confuse the boy’s identity and to take him outside himself so that he might assume a new identity when he rejoined the polis, that of a man. This ceremony would have been performed when a boy reached puberty and so would have combined hunting, change of identity and sexuality.

Perhaps this representation of initiation ceremony is too simplified to apply directly to myths of bestiality. Indeed, Forbes-Irving argues that the forms of initiation rituals are over-used as explanations for patterns and details in myth.24 Whilst I sympathize with his assertion that the possible influence that these rituals had on the formation of myths fails to explain fully their continued popularity and re-telling in future generations, it is nonetheless true that there are a number of details in myths in general that would appear to stem directly from sequences of events found in rites of passage rituals. As will become apparent, I believe that myths of bestiality and bestial rape are linked in structure and detail to such ceremonies in crucial respects. For this reason, I shall look more closely at male rites of passage ceremonies in this section and the location of hunting therein. In section IV, perhaps more importantly for the present inquiry, I shall look at their parallels with similar rituals undergone by girls.

As far as boys were concerned rites of passage marked their transferral from boyhood into the world of the citizen. Typically, the ceremonies would consist in a tripartite schema: a rite of segregation, the rites which accompany a state of ekstasis and a rite of incorporation.25 This schema worked in regard to the microcosm of initiands in opposition to the polis (or of the tribe, in other cultures), and in regard to the microcosm of the individual initiand in opposition to the group. The group would be taken to the wilds (the rite of segregation), and begin to undergo an intermittent state (ekstasis), which might involve a long sojourn from the polis. The Spartan agōgē appears to have involved such a rite.26 In this no-man’s-land, outside the boundaries of the polis and outside the control of civilization, the rites of ekstasis would occur, where the initiand would undergo a period of ‘standing outside’ himself, in that he would assume a new, temporary identity. As far as the band of initiands was concerned, this very group would form a temporary society, separate from the society of the polis and thus ’ekstatic’. Following initiands’ change of status to adulthood by means of various rituals (the rites of incorporation), initiates would re-enter as men, now with full citizen rights, the city they had left as boys.

For the individual, segregation entailed a separation from a former identity, that is, the leaving behind of boyhood. There would be various ways of effecting this, such as the dedication of the boy’s long hair,27 the dedication of toys, or perhaps the jettisoning of childhood clothes. However, before the boy’s incorporation into adulthood the intermediate, ‘ekstatic’ state would be assumed, which I shall call the ‘Other’, a state which plays an important role in female puberty rites, as we shall see. This intermediate, ‘Other’ state often involved cross-dressing and occasionally nudity.28 It is likely that it symbolically represented characteristics which it was important for the boy to deny. Thus dressing as a woman fulfilled a side of his nature, femininity, in which it would have been wholly inappropriate for him to indulge in his new role as a man.29

As I have already mentioned, hunting ritual was a constituent part of initiation ceremony, and would have taken place during the boy’s ekstatic period. The settings and context of initiation rituals particularly lent themselves to hunting, since hunting entailed a mastery of those elements antithetical to civilization. Hunting involved, then, a reaffirmation of man’s place above the animals in the Greek world order. The final purpose of initiation was, after all, the initiand’s integration into a civilized society at that society’s highest level–the level of citizen. Moreover, the hunt was appropriate both as a celebration of masculine activity and as a preparation for the role of hoplite in the similar all-male violent activity of war,30 an activity in which an initiate would be expected to partake as part of his new citizen status.

IV

At a pre-pubertal age, analogous to that at which boys would undergo rites of passage ceremonies, girls too would typically take part in rituals. In this section I shall attempt to analyse the nature and significance of female puberty rites, dwelling on those aspects of the rites which permit an insight into the patterns and details we find in myths of bestiality.

There is debate as to whether there existed such a thing as a rite of passage for girls attaining adulthood in ancient Greece. Vidal-Naquet argues that any such female rites are merely imitations of those ceremonies instituted for males and are in any case empty since a true rite of passage has to mark a change of status for the initiand.31 For a boy,his ascent into adulthood involved his acquisition of citizen rights, whereas for a girl no such boundary of status was to be crossed.32

Whether or not we can describe them as rites of passage, there certainly do seem to have existed such things as puberty rites for girls in ancient Greece.33 The best documented female ritual of this nature is the arkteia at Brauron in Attica. Here, girls of Athenian citizen families would pass four to five years of their lives as arktoi, ‘bears’,attendants of the goddess Artemis. Evidence from vase paintings suggests that ceremonies involved races in honour of the goddess, with the priests34 and priestesses dressing up as animals and wearing animal masks. Depending on their age, girls would race naked or clothed in saffron-coloured dresses.35 Lilly Kahil even postulates the involvement of real animals in the sanctuary’s rituals, as one Brauron vase shows a bear near Artemis’ altar.36

The parallels between male initiation ceremony and female puberty rite, in Attic practice at least, are numerous, if not exact. First, both sets of initiands spend time away from the relative security of the oikos and the polis, though the girls are still under the protection of the sanctuary. The nudity followed by the wearing of special garb would appear to follow the pattern of male initiation ceremony–separation followed by ekstasis, the special dress representing an integration into the micro-society of the sanctuary parallel with that formed by the male band of initiands. This would precede the girls’ re-incorporation into society at large following their return to the polis of Athens. Dressing in special clothes probably extended to the arktoi dressing as, or acting the part of, bears, as their name suggests. Thus the girls temporarily became an intermediate ‘Other’ located between childhood and adulthood. As boys would often dress as girls and then assume a ‘masculine’ nature in fulfilling the roles of men, so girls would dress as animals and then presumably assume a non-‘wild’ nature in fulfilling the roles of women.37

One role of the female rites would appear to be an induction from girlhood to physical womanhood–that is, a celebration of the attainment of menarche. As van Gennep shows, pubertal rites must necessarily be separated from the physical attainment of puberty as the timing of the latter is unpredictable.38 However, it can be postulated that the timing of the rites at Brauron had a connection with the ages at which girls were thought to begin menstruation. The writers of the Hippocratic corpus evidently saw fourteen as the modal age for menarche, and twelve as the earliest expected age.39 Estimates on the ages of the arktoi differ: Paula Perlman, for example, believes they began their service of the goddess at ten years and continued until they were fourteen or fifteen, although other scholars argue that their service might have ended at as young an age as ten.40 The arkteia could be thought of as recruiting girls at an age at which it could be assured that menarche had not occurred and finishing at an age when menses were at least imminent. Any protraction of the service to assure that girls had attained menarche would infringe the girls’ ripeness, as far as the Greeks were concerned, for marriage.41 If we are able to believe, then, that the Brauronian arkteia was indeed a pubertal rite, its purpose is to mark a girl’s attainment of fertility. Fertility would be worthy of marking, as the production of offspring was one of a woman’s chief functions in Greek society. Her ability for reproduction was key to her social role and vital to the polis at large.

The arkteia, then, may have fulfilled the function of a female rite of passage preparing a girl for marriage. However, it remains a moot point, and outside the realm of my argument, whether all girls received such a preparation or whether merely a representative, tiny and select handful were given the temporary privilege of being in the service of a deity.42

The major interest for our present enquiry is the linking, in more than metaphorical terms, of the girl and an animal. From here on, I shall call this state of animality the ‘Animal’. The explanation for the involvement of the bear in the arkteia is given in a myth where the girls are thought of as atoning for the death of a bear unjustly killed. Ancient writers stress the maternal instincts of the bear as being significant for its connection with the pubertal girl,43 but this does not explain the connection of the girls with the animals of similar cults, such as the goat, sacrificed in girl’s clothing at Mounychia,44 or the fawn, evidently important at the sanctuary at Larisa in Thessaly.45 To a modern analyst, the fact that animality is involved at all would appear far more important than the identity of the actual animal with which the cult associates itself. The ‘Animal’ is somehow particularly appropriate in the context of female initiation cult, representative of the female state on attaining menarche and of a girl entering the time of life when she is capable of reproduction. The nature of the ‘Animal’ metaphor will become the subject of the following section.

V

In this section I shall investigate other facets of Greek culture which show the adolescent girl identified with the ‘Animal’. We have already seen how the adolescent Greek girl is perceived in terms of the ‘Other’. Mary Douglas has noted the threatening nature of this state in tribal cultures:

...danger lies in transitional states, simply because transition is neither one state nor the next, it is undefinable. The person who must pass from one state to another is himself in danger and emanates danger to others.46

She also comments that individuals undergoing transitional states ‘are credited with dangerous, uncontrollable powers.’47 I suggest that a similar attitude is manifested in Greek writing and religious practice when a girl is perceived as an animal. There are characteristics possessed by a pubertal girl which render her identification with the ‘Animal’ appropriate. For example, her new ability to reproduce, owing to the onset of menarche, renders her threatening in that she is capable of conceiving a child outside wedlock, that is with no respect for the mores of civilized society.48 Such a wild union would be appropriate for animals, but not for civilized human beings. The possibility of a bastard child was a great concern for the Greeks, for whom the production of legitimate offspring was one of a woman’s chief goals.

The Greeks used animal metaphors for the pubescent girl. A girl is referred to as a πόρτις, calf,49 or a νεβρός, fawn.50 The leader of the chorus of Alcman’s Partheneion, Hagesichora, ‘is like a horse among the herds: strong, prize-winning, with thundering hooves, a horse of the world of dreams.’51 Greek men often saw beauty in animals, and girls were often spoken of in terms of worthy domestic beasts, as may be exemplified by Anacreon 417:52

Thracian filly, why do you look at me from the corner of your eye and flee pitilessly from me, supposing that I have no skill? Let me tell you, I could neatly put the bridle on you and with the reins in my hand wheel you round the turnpost of the race-course; instead, you graze in the meadows and frisk and frolic lightly, since you have no skilled horseman to ride you.53

This poem neatly embodies recorded male attitudes towards the adolescent girl. She has the potential of being beautiful, of serving a man well, of being ‘ridden’ by a δεξιόν ιππόπειρην (6)–surely a sexual metaphor–if only she should relinquish παιζειν (5), that is either ‘playing’ or, more literally, ‘being a child’. Presumably this involves consenting to sex.

Marriage is not only cognate with, but may be perceived as, the final stage of the taming process begun by female puberty rites. At marriage, the girl rids herself of her animality54 and is now a δάμαρ, wife or ‘tamed one’, since she has submitted to Aphrodite’s yoke.55 This taming is intended to curb any potential for sexual abandonment the girl might be capable of developing.56 Δαμάζώ and δάμνημι are verbs commonly used for a woman’s marriage, seduction or even rape.57 Her ‘breaking in’ now makes her acceptable as a member of the male dominated oikos which lies at the heart of civilization for most Greeks, although her continued confinement within that oikos demonstrates that her animal nature is not believed to have wholly disappeared. Her domestication is, however, necessary for the oikos to prosper, in that women are needed for the continuation of the family line. As Helen King remarks:

The Greeks saw ‘woman’ as a contrast between the undisciplined threat to social order and the controlled reproductive gynē. 58

VI

I now wish to examine the structure of one particular kind of myth within the context of the foregoing discussion, namely that of the pursuing god ravaging the pursued maiden. This is the most common type of ‘bestial’ myth and it takes one of three forms: (i) the god is transformed into an animal and rapes the girl; (ii) the girl is transformed into an animal but is nonetheless raped; (iii) both god and girl are changed into animals before the sexual act. Below is a table outlining the key features of those myths of bestial rape which fit the above patterns:

(i) the god is transformed into an animal and rapes the girl.

| Girl | Rapist | Offspring of the Union |

| Antiope | Zeus as a satyr | Zethus and Amphion, the first men to fortify Thebes |

| Canace | Poseidon as a bull | Hopleus, Nireus, Epopeus,Aloeus and Triops |

| Dryope | Apollo as a tortoise | Amphissus, the founder of and a snake Œta |

| Europa | Zeus as a bull | Minos, Rhadamanthys and Sarpedon |

| Leda | Zeus as a swan | Helen, Polydeuces, (Castor) |

| [versions of the myth differ greatly: see appendix] | ||

| Melantho | Poseidon as a dolphin | none known |

| Persephone | Zeus as a snake | Zagreus/Dionysos |

| Philyra | Kronos as a steed | Cheiron the centaur |

(ii) the girl is transformed into an animal but is nonetheless raped.

| Girl | Rapist | Offspring of the Union |

| Metis (a shapeshifter) | Zeus | Athene |

| Psamathe as a seal | Aeacus | Phocus |

| Taygete as a deer | Zeus | Lacedaemon |

| Thetis (a shapeshifter) | Peleus | Achilles |

(iii) both god and girl are changed into animals before the sexual act.

| Girl | Rapist | Offspring of the Union |

| Asterie as a quail | Zeus (or Poseidon) | none known |

| as an eagle | ||

| Nemesis as a goose | Zeus as a swan | Helen |

| Theophane as a bird | Poseidon as a ram | The ram with the |

| golden fleece |

It is difficult to construe bestial rape as anything but highly degrading for the girl. In myth in general there are numerous examples of women committing suicide after being raped,59 or being metamorphosed so they no longer participate in the world as human beings. The girls raped in ‘bestial’ myths tend to be virgins, so rape entails a double dishonour for them as they lose their chastity too.

When a myth represents a girl as involved in an act of bestial sex she is being intimately linked with an animal and animal forces. As we have seen, a young girl is often associated with the ‘Animal’ in initiation ritual, and spoken of in terms of the ‘Animal’, whereas man is often spoken of in terms of her potential tamer. Although girls are not always metamorphosed into animals in myths of bestial rape, it can still be viewed as significant that gods who rape them often choose to do so in animal form. The connection which the girls concerned have with the ‘Animal’ is shown as extending to the realm of sexuality. Often, as in the case of Leda and Dryope, the girls are attracted to the animals into which the raping gods have metamorphosed themselves. Underlying the assault of the pubertal girl by the god in animal form may well be the Greek notion that ‘like goes to like’, τόν ὅμοιόν φασι ώς τόν ὅμοιον.60

Myths of bestial rape would appear to have a connection with the institution of hunting. For example, the setting of these rapes is always the wilds. What is more, the parallel of erotic pursuit and the pursuit of the beast for killing is attested in Greek literature and art. Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood has written on the similarities between youths’ costume and posture on vases when they are hunting prey and when they are chasing women.61 Hunters may also have practised sexual abstention, as this effects a hormonal change in the male which builds aggression.62 As Burkert notes, whether this aggression is eventually displayed in the form of a kill or in the form of rape is almost accidental.63

As we have seen earlier, in cultures where hunting is practised, the hunter often identifies with his quarry, as is exemplified by his dressing up as the hunted animal. Such an identification might explain the fact that the gods in bestial rape myths–hunters pursuing this time a sexual prey–often take an animal form. Furthermore, hunting usually entails the use of guile in order to catch the prey: for a human hunter this might involve the use of weapons such as a bow and arrow, the use of traps or nets, or the use of techniques such as employed by the Blackfoot Indians, as detailed earlier, whereby buffalo are led into a corral.64 When the hunter is a god, a more sophisticated guileful technique is open to him–that of metamorphosing himself into an animal.

The victims of bestial rape suffer one of two fates: either to undergo some form of punishment, or else, perhaps surprisingly, to be reintegrated into society and with no apparent stigma attached. The deciding factor as to their eventual fate seems to be whether or not they resist their assault. A girl who attempts to escape rape by her pursuant god might, for example, stay in a metamorphosed state. It is as if, at puberty, the virgin is neither girl nor woman, but a third, ‘Other’ kind. Without acquiescing to sexual intercourse with an appropriate partner, mortal girls cannot escape their pubertal roles; they remain in an ‘Other’ state for ever (non-mortals such as Thetis and Metis are, however, able to resist assault and to change their shape with impunity). An example of a girl who stays in a metamorphosed state is Asterie. Following her rape, she is metamorphosed into a floating island which later becomes Delos.65 Philyra, in one version of her myth, is ashamed at her rape by Zeus and is turned into a linden tree. The permanent metamorphoses undergone by these girls render them unable to rejoin civilization.

It is a platitude when talking of myths of rape to say that they are expressive of a power schema, the male aggressor being the controller and the female victim the controlled. I believe that various elements of the Greek world view, such as the idea that man’s superiority to woman is part of the natural world order, have become encoded in these myths, where they have taken on a highly dramatic form. If ‘bestial’ myths were to be read literally, the lessons that the girl might be expected to learn from them are as follows: (i) since the wilds are a place where a girl might be raped, she should stay within the boundaries of controlled civilization; (ii) resisting sexual activity with a male might lead to an undesired metamorphosis, so she should submit to sex. However, giving in to her lust can have bad results. This can be exemplified by another ‘bestial’ myth, that of Polyphonte, who falls in love with a bear. In Polyphonte’s case he children to which she gives birth are wild, whilst she herself is detested by the whole animal world.The myths are to be understood more convincingly if decoded–that is, if they are read as a metaphorical or hyperbolic exemplification of social attitudes and expectations. The resulting message for the girl, if we may call it this, is that since there is no escaping male control, a woman might as well submit in an appropriate context, that is, within the context of the mores of human society and the city-state. Resistance to sexuality can lead to social exclusion. In myth, this is realized in terms of a permanent metamorphosis, such as that undergone by Daphne. She resists sexuality, and her transformation into a laurel tree places her outside civilization for ever.66

Most of the girls who are victims of bestial rape are reintegrated into society. Dryope is raped by Apollo, who is in snake form, but she is soon married to Andraemon, and Amphissus, Dryope’s son, who is conceived through her union with Apollo, is reared as Andraemon’s own. After being raped by Zeus, Europa is married to Asterius, the King of Crete. He helps to rear the sons she conceives through her bestial union, namely Minos, Rhadamanthys and Sarpedon. The examples of heroic offspring from bestial unions are numerous. Figures such as Athene, Pegasus, Cheiron, Achilles and the Dioscouri are all, in at least one version of a myth, such products.67

These bestial rapes are committed by gods who are symbols of civilization; there is no account of Dionysos committing such a rape, for example. Instead, amongst the terrestrial gods, it is Zeus and Apollo who are the perpetrators of rape, both of them interlopers in the wilds (gods of the sea and of rivers form a separate category of metamorphosed rapists68). Through a form of sanctioned rape, the male is able to control the female. The wilds represent a location particularly appropriate for the rapes to occur. They are an antithesis to the order of the polis, and a place of divergent sexuality where women are sometimes virgins, such as Artemis and her band. In myths of bestiality, virginity is controlled by the other form of divergent sexuality which the wilds represent–that of animal lust.69

The power of lust is, I believe, an important theme in myths of bestiality. The raping god does not have his desire abated even when the object of that desire, the fleeing woman, is metamorphosed.70 Nor does it matter to a god if the woman is not attracted by him but rather by the animal into which he has changed himself, such as a bull, in Europa’s case, or a tortoise in the case of Dryope. Bearing in mind that girls in Greece were married at puberty, perhaps it would not be unfair to see an identification between this form of rape and the fears of girls on the verge of marriage. Girls may feel that on marriage, they too will be confronted with a faceless, sexually desirous male force. However, the myths show that by acquiescing in this masculine sexuality in an appropriate context they will reap benefits. In the cases of these myths the ‘appropriate context’ is when the force is divine. In the myths the children conceived through bestial rape often become heroes, and the girl who conceives them is reintegrated into society. Indeed, the raped girl might even attain higher status than her peers through having borne heroic offspring. Such details in the myths can be viewed as didactic, since the implication is that the girl who submits appropriately to sex will bear healthy children and find herself in a role in society where she will find acceptance. In a similar way, marriage and the production of offspring will, in the real world, be beneficial to the girl, and presumably less harrowing than, although still analogous to, the bestial rape of myth.

It would appear a strange anomaly that the girls raped in myths of bestiality suffer no evil consequences for bearing illegitimate children. If a girl were raped by a man in classical Athens, for example, she might well be considered unfit for marriage, whether she conceived a child or not.71 It is as if the status of the rapist as divine rather than human somehow sanctions the rapes and adds to, rather than detracts from, the girl’s value to the community.

I believe that these myths explore the three following facets of the Greek world-order:

(i) Men’s superiority over women. First, women are degraded in these myths simply by being raped. Second, in the context of rape they are identified with the animal victim of the hunt and are thus treated as something sub-human. The myths also help to define women’s social space as being within the polis, that is, within a domain which is under the control of men.

(ii) Women’s role in society. This is to undergo a marriage in accordance with social mores and to provide their husbands with healthy offspring.

(iii) The place of man in relation to the gods. A god can confer special social status on a woman by raping her. In real life, on the other hand, rape by a man would entail a girl’s dishonour. Thus gods are seen to have powers which men do not. This aspect of the myths will be explored more closely in section VIII.

VII

In this section I shall examine the form marriage took in ancient Greece. I believe that details of the various wedding ceremonies of different city-states and ancient views on the bride’s role within wedlock lend weight to the theory that bestial rapes in myth are linked to female fears of marriage.

First, there is the timing of marriage, which in most city-states occurs shortly after the girl is thought to have attained womanhood.72 Indeed, the rites, such as those at Brauron, are often discussed, both by ancient authors and modern scholars, in their capacity for preparing young girls for marriage.73 Her early teenage years, an age at which an initiate might leave Brauron, would be a fairly typical age for a girl in Athens to marry. The Greek fear that a girl might become pregnant out of wedlock, and thus unmarriageable, would no doubt add to a kurios’ zeal to have the girl under his care married as early as possible. A girl who was raped may well have been considered unfit for marriage, and a girl was also believed to be at her most attractive when she was a parthenos,74 that is ‘unmarried, yet at the age for marriage’,75 and so most at risk from sexual assault or, more realistically, from seduction.76 The girls in rape myths seem to be at this age themselves, as they are always particularly attractive and, in any case, myths concerning women tend to centre around girls of marriageable age.77

The connection between myths of rape and the actualities of marriage has been noted before, the most obvious parallel being that marriage marks a girl’s first sexual union with a man. Paula Perlman has noted that the girls raped in myth are alone, without the protection of their families, and that this ‘might foreshadow the marriage situation.’78 Needless to say, however, there are important differences between marriage and rape. A girl had time to prepare for and to grow accustomed to the idea of marriage. Also, in marriage the girl would have had the support and approval of her family. I propose, however, that rape can be viewed as a mythical embodiment of marriage, since it can be regarded as cognate in crucial respects. The location of bestial rape myths in the wilds, for example, might well be a detail that stems from a girl’s marriage being one of the few times in her youth that she was permitted outside the control of the parental oikos apart from in exceptional cases; her place of residence from her wedding day onwards would be her husband’s oikos, an unfamiliar setting. Marriage marked a significant and potentially frightening change of status for the bride;79 indeed, it was common for a marriage to be envisaged in terms of a funeral.80

Marriage represented the final stage in the process of transition that a girl began on her removal to the cult sanctuary in her pre-pubescent years, her marriage entailing a change of status and a transition over and above that already undergone. For a girl who had not attended the sanctuary, marriage represented the process of transition in its entirety. At her wedding the bride would wear special clothes, and the initiation pattern of segregation, ekstasis and incorporation would be undergone. Her segregation was marked by rituals such as the dedication of her childhood toys.81 One day of the three-day ceremony was devoted to the girl marking the end of her childhood. In Athens, the bride’s ekstasis was marked by means such as her donning the bridal gown and veil.82 In Sparta, brides shaved their heads and dressed as boys, and in Argos brides wore beards.83 The bride had to become an ‘Other’ before she could undergo her transferral. Then came the process of her incorporation–her journey to the marital oikos, the completion of the marriage rituals, part of which, in Athens, took the form of an adoption ceremony similar to that used for the adoption of children or new-bought slaves.84

The ‘Other’ state which the bride entered during her process of ekstasis might well be encoded in myth in the same way as the ‘Other’ state entered by the adolescent girl in pubertal rites, that is, as the ‘Animal’. After all, the two processes would appear to be co-dependent and closely linked in timing and purpose.

VIII

My purpose has been to focus on one type of bestial rape in this paper. In this section I shall discuss other myths of bestiality–both bestial rape myths which have been less well covered by the framework of this paper and myths concerning female lust. Subsequent to this, I shall attempt to draw some conclusions as to how the structure of bestial myths relates to the Greek world view.

The myths of bestial rape that have not been covered in this paper involve figures which Forbes-Irving terms ‘shape-shifters’.85 These tend to be older sea-borne gods, somehow outside the control of the Olympian gods and representing the older, more chaotic elements of the universe. Part of this chaotic character is displayed by an ability for sexual behaviour antithetical to that of the polis. To this category belong such figures as Proteus, Thetis and the river god Achelous. Poseidon, who is involved in a number of bestial rapes, is of ambiguous status as far as this category is concerned. He is a civilizing god in that he is Olympian, and in this capacity imposes a certain amount of order on the maritime world. However, he also belongs, by association, to this same, slightly mysterious and ever-changing world and so may be perceived as having chaotic and changeable elements of his own.86

The other category of bestial myths I have not covered is that of myths concerning female lust. Myths such as those of Polyphonte and Pasiphaë demonstrate what happens when a woman loses control of her sexual urges. Female passion is always punished. These myths represent female passion in an extreme form–women falling in love with animals. The women’s offspring are always wild. The Minotaur, Pasiphaë’s child, suffers a premature death and is the cause of the family’s dysfunctionality, in that its sister, Ariadne, aids its death and is seduced and then abandoned by its slayer.87 Bestial myths, then, have the effect of defining what sexual behaviour is suitable for a woman: a woman must submit to an appropriate male, and must not herself be the instigator of the sexual act.

Rape can be viewed as a mythical embodiment of the male’s capacity for the defence of the city-state. A man effects this defence in real life in the form of war against another people. The role of a hoplite is one for which, as we have seen, the boy is prepared on his initiation through the analogous ritual of hunting. A god, on the other hand, in myths of rape, defends social mores by violent action on a similarly potentially dangerous group of people–women. This war is waged in order to ‘tame’ young women so that they will continue the city-state through the production of legitimate offspring, union with a god being analogous to an appropriate marriage. The female body becomes the object of a mythical hunt. Both male and female are represented in bestial myths in terms of aspects of their pubertal selves: the female appears as prey to be hunted, often a wild animal; the male, in these myths a god, as a hunter.88 Often, the guile used by hunters, which may have included dressing as an animal, is shown in myth as the hunter becoming an animal, a metamorphosis easily enabled by the fact that the hunter is a god, and thus capable of physical changes. When a human copulates with an animal, or even when two animals copulate, the emotional responses which it is possible for humans to have in respect of one another are necessarily lacking. This is also true of rape. In this light, then, even when the girl involved in a bestial rape does not actually become an animal, her involvement in an act of sex which has been depersonalized shows that she is being treated as something other than wholly human.89

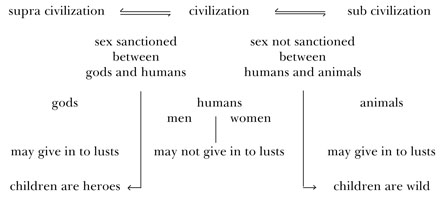

These myths of bestiality help to uphold and define the order and institutions of the polis and the social role of the male as superior to that of the female, in that he is the female’s subjugator. What these myths also uphold is the Greek world-order.90 The Olympian gods are the rapists in these myths; that is, their power and authority is used in maintaining the social order. Union with a god means social successfor a woman, as her children will be heroic, whereas the opposite is true of union with an animal. In the Greek world-order gods are above human civilization, whereas animals are below it. The female nature is seen to overlap with the animal, and so, by implication, the male nature is closer to the divine. However, both gods and animals, at either end of the spectrum of the world-order, are able to exercise their will without restriction. Neither is confined by the rules of civilization and so both can exercise their sexual desires freely. Humankind is burdened by rules which govern its behaviour, and since humans only rarely become immortal in myth, violation of social mores usually threatens the destruction of civilization, through a sliding towards a state of animality rather than towards the divine. Since women are closer to the animal state already, they are more in danger of becoming wild. My conclusions can be expressed by the following diagram (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1.The Greek world-order as established by myths of bestiality

IX

In the course of this paper I hope to have shed some light on the social factors which might have shaped the formation of myths of bestiality and which might have led to their continued re-telling by successive generations. By investigating the details and the underlying structures of myths of bestiality, I have argued that these myths help to define and uphold both the institutions of the city-state and the Greek world order. I have argued that bestial myths highlight: (i) men’s superiority to women, (ii) women’s role in society, and (iii) the place of humans in relation to the gods. I have attempted to locate bestial myths alongside myths of rape and hunting.

I believe the myths were didactic, yet, along with this, that they were symbolic, not only of male attitudes towards the adolescent, marriageable female, but also of these women’s views of marriage and male sexuality. During the course of my discussion, I hope to have shown how the patterns and details of these myths can be located within, and correspond to, everyday experiences and expectations of the ancient Greeks. If my suggestions are of any substance, then these myths are of particular interest in that they might help us to reclaim some of the female perspective on life in the ancient world.

Appendix of Myths

The following is a list of bestial myths cited in the main body of the text. For those myths for which few references in literature survive all the extant sources are given. For those tales better documented, references are given to the earliest versions of, fuller treatments of, and interesting variations in the myth. For visual representations of the myths, the reader is referred to the Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC), ed. Cristoph Ackermann and Jean-Robert Gisler, Vols. 1-7, pts. 1 and 2 (Zurich).

Antiope

Both Ovid and the scholiast on Apollonius Rhodius mention that Antiope is raped by Zeus who is disguised as a satyr. In Apollodorus, as in other sources, there is no mention of bestiality. Rather, she is raped by Zeus and subsequently marries Epopeus. As a result of the union with Zeus, she bears two sons: Zethus and Amphion. These become the first men to fortify Thebes.

Apollod. 3.5.5

Hyg. 7 and 8

Ov. Met. 6.111-12

Propertius 3.15.11-42

schol. Apollon. Rhod. 4.1090

See also Webster 1967 and Seaford 1990, 84 ff. on the lost Antiope.

Asterie

Zeus, in the guise of an eagle, seizes Asterie, who is metamorphosed into a quail. Following her rape, Asterie is metamorphosed into a floating island, which later becomes Delos.

Apollod. 1.4.1

Call. Hymn. 4.35-40

Hyg. 53

Ov. Met. 6.108

See also Nonnus, Dion. 2, for the version that Poseidon was the pursuer.

Canace

Canace is raped by Poseidon who is in the form of a bull. In Apollodorus, she is said to have borne Poseidon five sons: Hopleus, Nireus, Epopeus, Aloeus and Triops–but no mention of the metamorphosis is made.

Ov. Met. 6.115-16

Apollod. 1.7.3-4

Demeter

The Black Demeter of Phigalia and the Demeter Erinys of Thelpusa were both said to have mated in horse shape with Poseidon, who was also in the shape of a horse. The offspring was either a foal or the goddess, Despoina.

Ov. Met. 6.118-19

Paus. 8.25.4 ff. and 8.42.1 ff.

Dryope

Apollo conceives a passion for Dryope, a shepherdess, when he sees her dancing. He seduces her in the form of a tortoise and mates with her in the form of a snake. Saying nothing of the rape to her parents, she is married to Andraemon. She bears Amphissus as a result of her union with Apollo, who is brought up as if Andraemon’s own. Amphissus grows up to be a hero and a king. Dryope is seized by nymphs who make her immortal.

Ant. Lib. 32

Ov. Met. 9.329-93

Europa

Zeus comes to her in the form of a beautiful bull when she is playing on the beach. She climbs on the bull’s back and he carries her away to Crete. As a result of the union she gives birth to Minos, Rhadamanthys and Sarpedon. She is married to Asterius, the king of Crete, who adopts her sons.

Apollod. 2.5.6 and 3.1.1

Hyg. 155 and 178

Moschus 2

Ov. Fasti 5.604

Ov. Met. 2.833-75 and 6.103-7

See also Johns 1982, 110. There are numerous depictions of Europa both in vase painting and plastic art. These tend to show her either adorning or riding the bull (See LIMC, Vol. 4.2).

Ganymede

Ganymede is snatched by Zeus to be his cup-bearer since he is the most beautiful boy in the world. In post-Homeric versions Zeus either sends an eagle or comes in the form of an eagle. The bestial version of this myth is a late version most likely imitative of the other bestial myths, all of which have heterosexual themes.

Hom. Il. 20.232-5

Hom. Hymn. Dem. 202-8

Hor. Odes 4.4

Hyg. Astr. 2.16

Ov. Fasti 6.43

Ov. Met. 10.155 ff. and 11.756

Pind. Ol. 1.40-5

Verg. Aen. 5.255 ff.

See Bruneau 1962 on depictions of the rapes on vases. There are a good deal of representations of Ganymede’s abduction by Zeus as a man, but more with Zeus shown as a bird. Plastic representations almost exclusively represent Zeus as a bird.

Leda

In versions of the myth from classical times and beyond, Zeus rapes Leda in the form of a swan. There is conflict amongst the sources as to the offspring of the union. In Homer, Leda is said to bear Castor and Polydeuces to Tyndareus, but Helen is said to be Zeus’ daughter. In the Homeric Hymns, the Dioscuri are said to be Zeus’ offspring. In Pindar, Polydeuces is Zeus’ son, whereas Castor is Tyndareus’. In Apollodorus, she is said to bear Polydeuces and Helen to Zeus, and Castor and Clytemnestra to Tyndareus. In Euripides Iph. Aul., Leda is also the mother of Phoebe. Apollodorus also cites a version of the myth in which Leda merely finds and hatches an egg previously laid by Nemesis.

Apollod. 3.10.7

Eur. Hel. 16-22, 257-9; Iph. Aul. 49-51, 794-800.

Hes. fr. 23a, 7-10

Hom. Od. 11.298-304

Hom. Hymn. 17 and 33

Hyg. 77

Ov. Amores 1.10.3

Ov. Her. 16.294 and 17.55-6

Ov. Met. 6.109

Paus. 3.16.1

Pind. Nem. 10.79-82

Sappho fr. 166 Voigt

Medusa

According to Ovid, Poseidon, in the guise of a bird, rapes Medusa in the temple of Athena. As a result, she bears Chrysaos and the winged horse, Pegasus. Hesiod also describes the birth of Medusa’s offspring, but here there is no bestial aspect to the myth and the sexual act takes place in a meadow.

Hes. Theog. 278-81

Ov. Met. 4.785-6, 798-9 and 6.119-20

Melantho

Poseidon, in the form of a dolphin, rapes Melantho.

Ov. Met. 6.120

Metis

Metis changes shape many times while Zeus tries to rape her. The product of their union is Athene, who is born from Zeus’ head after he swallows Metis whole.

Apollod. 1.3.6

Cf. Hes. Theog. 886 ff., where no metamorphosis is mentioned.

Nemesis

In an alternative version of the Leda myth, Nemesis is said to have been raped by Zeus, he in the form of an eagle, she in the form of a goose. The offspring of the union is Helen.

Apollod. 3.10.7

Sappho fr. 166 Voigt

Olympias

Plutarch relates the story that Olympias mates with Zeus, who comes to her in the form of a snake. The offspring of the union is Alexander the Great. This is an interesting example of a sequence of events common in mythology being related as having occurred in the life of an historical figure.

Plut. Alex. 3.1-2

Pasiphaë

Minos prays to Poseidon (or Zeus) to send him a bull to sacrifice so that the question of whether or not he should be king may be settled. Poseidon grants Minos’ request, but on seeing the beautiful white bull that is sent, Minos decides to keep it for himself and to sacrifice another in its place. As punishment, Minos’ wife, Pasiphaë, is caused to fall in love with the bull. The craftsman, Daedalus, fashions a wooden cow for Pasiphaë to crawl inside so that she might attract the bull and consummate her passion. The product of the union is the Minotaur.

Apollod. 3.1.3-4

Diod. 4.77

Eur. Cretans

Hyg. 40

Ov. Ars Am. 1.289-326

Philostr. Imag. 1.16

Virg. Aen. 6.24

Virg. Ecl. 6.45 ff.

On the lost Euripides play, see Page 1942, 70-6.

Persephone

Zeus in serpent form approaches Persephone. Following the union, she has a son, Zagreus, to whom Zeus intends to give all the power in the universe. However, he is murdered by the Titans and Hera. Athene manages to save the boy’s heart, which is swallowed by Zeus, and through which Zeus begets Dionysos.

Callimachus fr. 43.117 Cic. de N. D. 3.23.58 Diod. Sic. 3.61.1 Firmieus Maternus De errore, 6 Nonnus Dionys. 6.155 ff. Ov. Met. 6.114Philyra

There are two versions of this myth in which Philyra is raped by Kronos. In one, Kronos commits the rape in the shape of a steed. In the other, he changes his shape after the rape, as Kronos’ wife, Rhea, catches him in flagrante delicto. The product of the union is the centaur, Cheiron. After the rape, Philyra is metamorphosed into a linden tree. In Hyginus, Philyra requests this metamorphosis from Zeus. Apollonius Rhodius says that she leaves the scene of the rape ‘in shame’ (οάδοί: 2.1238).

Apoll. Rhod. 2.1231-41

Ov. Fasti 5.383, 391

Ov. Met. 6.126

Val. Fl. 5.153

Virg. Georg. 3.92-4

Polyphonte

Having scorned the activities of Aphrodite, Polyphonte joins Artemis’ band of nymphs in the mountains. As punishment, Aphrodite drives her mad, making her fall in love with a bear. She bears two sons, Agrius and Orius, who are strong and scorn the gods and civilization. They are also cannibals. Antoninus Liberalis 21

Psamathe

Psamathe is a sea maiden and the daughter of Nereus. In Apollodorus, she tries to resist the attentions of Aeacus by changing herself into a seal, but in vain. She bears a son, Phocus, who is renowned for his athletic prowess. According to Euripides’ Helen, she later marries Proteus and bears him children. In Hesiod and Pindar there is no mention of the metamorphosis.

Apollod. 1.2.7 and 3.12.6

Eur. Hel. 6-15

Hes. Theog. 1003-5

Pind. Nem. 5 12-13

Taygete

Zeus pursues Taygete, who is the daughter of Atlas. In one version of the myth, Artemis turns her into a deer to help her flee, but Zeus, undeterred, rapes her in this form. In another version of the myth, her metamorphosis enables her to escape Zeus’ advances; as a token of thanks she subsequently gives a deer as an offering. She begets a son, Lacedaemon. Later, she becomes a star.

Diod. 3.60.4

Eur. Hel. 381-3

Hyg. Astr. 2.21

Hyg. 155 and 192

Ov. Fasti 4 174

Paus. 3.1.2; 3.18.10

Pind. Ol. 3.29-30, and scholia on this passage; Ol. 3.53

Poseidon abducts Theophane to an island where he copulates with her, he in the form of a ram, and she in the form of a bird. The offspring of their union is the ram with the golden fleece. Hyg. 188

Ov. Met. 6.117

Thetis

Thetis is assaulted by Peleus, who wishes to marry her. In an attempt to avoid his attentions she turns herself into a number of animals. Later the two are married and Thetis bears Achilles. In Apollodorus, the betrothal and marriage of Thetis are related with no mention of the rape. Lycophron says that seven children are born to Thetis, only one of whom survives her attempts to make them immortal.

Apollon. Rhod. 4.805-8

Cat. 64.31 ff.

Hom. Il. 18.55 ff.

Lycophron 178 Ov. Met. 11.221–65

Pind. Pyth. 3.92 ff.

The rape and wedding of Thetis are popular themes in sixth century art.

Notes

1 In various stages of its metamorphosis, this paper has been read at the Rape conference at Cardiff in November 1994, as well as to seminar groups at King’s College London and the Institute of Classical Studies. I am grateful to all of those present for their useful comments. Particular thanks are due to Dr E.E. Pender, Dr A.H. Griffiths, Dr N.R.E. Fisher, Mr D. Harvey and Ms S.J. Deacy for their many helpful suggestions.

2 See Lefkowitz 1986, 12–13.

3 Pace Tyrrell and Brown 1991, 103.

4 After all, the diverse possibilities for the interpretation of myth are, no doubt, part of myth’s appeal; it is not myth’s magic I mean to quench.

5 A less sexually explicit modern portrayal of bestiality can be witnessed in Woody Allen’s ‘Everything you ever wanted to know about sex...but were afraid to ask’, where the Gene Wilder character has an affair with a sheep.

6 Johns 1982, fig. 26; Lissarrague 1990, fig. 2:19, London B446; fig. 2:20, Munich 2422; Dierichs 1993, fig. 204.

7 Lissarrague 1990, fig. 2:3 and fig. 2:22; Schefold 1992, pl. 48.

8 Berlin 1964.4: Kilmer 1993, R226 = Dover 1978, R1127 = Keuls 1985, pl. 262.

9 Sourvinou-Inwood 1991, 81: Kilmer 1993, 17–18, n. 14, says that Pan and satyrs are often depicted as ithyphallic on red-figure vases, whereas this is never the case with Olympian gods such as Zeus and Poseidon.

10 Such as Thebes 3691: Dierichs 1993, fig. 203.

11 Such as Naples 27.609: Johns 1982, fig. 92 = Lissarrague 1990, fig. 2:27.

12 See Dierichs 1993, 104–10 and figs. 189–92 and 194a and b. What these rapes have in common is that they lend themselves to elegant depiction.

13 See Dekkers 1994, 133, for agreement on Kinsey’s findings on bestiality.

14 Dekkers 1994, 119–24.

15 Ibid., 126. See also Rosen 1979, 423.

16 Cf. Paus. 10.13.1–3, where the similar hunting methods of the Paeonians are described.

17 Campbell, J. 1959, 283–4.

18 Ibid., 286.

19 Ibid., 302–3.

20 Burkert 1983, 18.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid., 64 and n. 25. The Chukchi are a people of north-eastern Siberia.

23 On the constitution of the wilds and their significance, see Detienne 1979, 24–5; cf. Segal, C. 1981, 61 and 65; Vidal-Naquet 1986, 138, 144.

24 Forbes-Irving 1990, 50–7.

25 In van Gennep’s schema (van Gennep 1960, 83) ‘transition’ is the stage between segregation and incorporation, a term which I feel to be ambiguous, not least through van Gennep’s use of it, for he makes it stand for both the transitional state (which I term ekstasis) and the ceremony of transferral into the new state from the ekstatic state (i.e. incorporation). Central to my thesis is the existence of a concrete, intermediate tier to these rites, ekstasis, one which is certainly well attested. Vidal-Naquet 1986, 138, talks of this state as ‘exclusion’ and discusses the processes of ‘marginality’ talking of the ceremonies which precede and terminate what I term ekstasis thus, 138: ‘...the ritual itself causes the initiate to pass from the ordinary to the extraordinary and back again to the ordinary, now consciously accepted.’ On Vidal-Naquet, see also Segal, R. 1991, 83.

26 See Vernant 1987. During the agōgē, youths would be excluded from public places, and in spheres such as eating, dressing and washing, would maintain practices at variance with those of normal Spartan society.

27 Vidal-Naquet 1986, 144 and 149. Although at Sparta males would have shorn hair as children and long hair as adults.

28 On nudity, see Perlman 1983, 125, n. 53. The Greeks appear to have been concerned that human nature could be over-confined in certain respects; hence, many poleis had festivals which involved male cross-dressing, and female festivals such as the Thesmophoria at Athens or Bacchic thyrsi, where women were temporarily released from the confines of the oikos. Part of the purpose of these rituals was to provide a period of release from the roles required of those resident in the polis, culminating in a conscious acceptance of that person’s position in the polis when the position was resumed. See Bullough 1976, 117.

29 Cf. Vidal-Naquet 1986, 139.

30 Detienne 1979, 24–5.

31 Vidal-Naquet 1986, 147.

32 There has been debate as to whether the process of ‘initiation’ into a quasi-female citizenship as described by the chorus of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata 453 ff., has any grounding in reality. Most scholars conclude that the envisaged pattern of female ‘initiation’ represented in this passage is Aristophanic invention. See Perlman 1983, 115; Cole 1984b, 238, n. 29; Vidal-Naquet 1986, 145; Bruit Zaidman and Schmitt Pantel 1992, 67.

33 On the ‘puberty rites’ of girls, see van Gennep 1960, 65–115, esp. 65–8.

34 On the presence of male priests at the sanctuaries, see Kahil 1977, 92–3

and pl. 20.

35 Perlman 1983, 125.

36 See Kahil 1977, 91 and figs. 3, 4 and b.

37 Detienne 1979, 31; Cole 1984b, 242; Bruit Zaidman and Schmitt Pantel 1992, 71. See also Ael. VH 13.1. Cf. Forbes-Irving 1990, 64.

38 van Gennep 1960, 65–8.

39 Oribas. Ecl. Medic., 132.1. See Amundsen and Diers 1969; Perlman 1983, 116 and n. 9.

40 Perlman ibid. et passim. Clement 1934, 397, also argues for an age band of 10 to 15. Kahil 1977, 86, estimates that the age limits are 8 and 13, whereas Just 1989, 232, estimates an age band of 5 to 10. A lower age band for the initiands than 10 to 14 becomes convincing when we consider that Artemis was the goddess of virginity. Menstruation may well not have been desirable or even permitted in the sanctuary. This need not change the fact, however, that the arkteia was perceived as a puberty rite.

41 See Lacey 1968, 107 and Bruit Zaidman and Schmitt Pantel 1992, 68 for Greek attitudes towards the suitable age of marriage for a girl. Lefkowitz 1986, 33, refers to a Hippocratic treatise, Virg. 50.8.468, which states that, ordinarily, a woman should be married off at the first sign of puberty. This might well be in order to avert the danger of illegitimate offspring.

42 Bruit Zaidman and Schmitt Pantel 1992, 67.

43 See Cole 1984b, 241, who cites Arist. HA 579a, 18–35; Plut. De Amor. Prol. 494c; Ael. NA 2.19. See also Oppian Cyn. 3.139–82 for the ancient belief that female bears were highly lustful.

44 Ibid., 120; Clement 1934, 397, also argues that goats were sacrificed at the arkteia.

45 Clement 1934, 402. Attendants of Helen at Sparta were called πωλοι, foals: see Griffiths 1972, 24.

46 Douglas 1966, 96.

47 Ibid., 104.

48 This fear is made tangible in comedy where women are often portrayed as lusty and drunken. Comedy as a medium often confronts taboos and inverts social values. Cf. Lefkowitz 1986, 55.

49 Hom. Hymn. 2.174 ff.; Soph. Trach. 529–30; Lycophron 102.

50 Hom. Hymn. 2.174 ff; Bacchylides 12 (13) 87; Eur. El. 860.

51 Lefkowitz 1986, 58, on Alcman 1.43–9. Women are also compared to horses at Ar. Lys. 1308–10; Semon. 7.57 ff.; Lucil. 1041–2; Theogn. 257–60.

52 See esp. Semonides 7, where ‘types’ of women are listed, including those resembling a sow, a pig, a vixen, a bitch, a donkey, a weasel, a mare, a monkey and (the one good woman) a bee. Forbes-Irving 1990, 64 notes: ‘sometimes the comparison suggests their physical fertility, sometimes their sexual appetite, and most commonly.it suggests that they are attractive or interesting to men.’ For a parthenos as a filly, see references in King 1983, 111.

53 Loeb/Page, 417; Bergk, 75; Diehl, 88; Gentili, 78. Text from Campbell, D. 1967; translation based on Campbell, D. 1988.

54 Sourvinou-Inwood 1991, 65, 75. Cf. Forbes-Irving 1990, 65 and n. 11.

55 See references at King 1983, 111. See also Segal, C. 1981, 65 on Soph. Trach. 536; Vernant 1980, 139.

56 Sourvinou-Inwood 1991, 68, 85.

57 See Vermeule 1979, 101; Cole 1984a, 98, and esp. 109; Lefkowitz 1986,

34–5.

58 King 1983, 124.

59 Forbes-Irving 1990, 62.

60 Arist. EN 1155a34, a common Greek sentiment: Od. 17.218; Pl. Gorg. 510b; Arist. EN 1155b7.

61 Sourvinou-Inwood 1991, 66, 80 and 91, n. 46. For homosexual pursuit described in terms of hunting, see Pl. Phaedr. 241d.

62 Cf. Burkert 1983, 59 and esp. 60–1.

63 Ibid., 59; cf. 64 and 65 for undercurrents of violence in sexual situations and vice versa.

64 See Segal, R. 1991, 84, on the ephebe hunter’s reliance on trickery.

65 Apollod. 1.4.1; Call. Hymn. 4.40; Hyg. 53.

66 Cf. Lefkowitz 1986, 36.

67 For details of the individual myths, see the appendix.

68 See section VIII.

69 For the dichotomy of abnormal sexual behaviour created by the wilds, see Vernant 1980, 139; Forbes-Irving 1990, 65.

70 See Devereux 1969, 86–7. Examples include Poseidon’s pursuit of Demeter and Zeus’ pursuit of Taygete.

71 Cole 1984a, 107.

72 Aristotle, Pol. 1335a, advises that girls be married at 18, saying that girls younger than this bear small and unhealthy offspring. Plato, Leg. 785b, advises that the girl be 16 to 20. It is likely that in reality, however, girls were married younger than this: Ischomachus’ wife in Xenophon, Oec. 7.5, is 14, and Pamphila in Terence’s Eunuch (a play of Greek origin?) is 16. In Gortyn, girls married at 12 or after: Inscr. Cret. 4.72.12.34. Certainly in some Greek states, such as Troezen, girls were married extremely young and at an age prior to menarche: see Arist. Pol. 1335a, and the discussion of this passage by Newman 1902, 464.

73 On ancient sources see Perlman 1983, 116 and n. 6 and Vidal-Naquet 1986, 140. Kahil 1977, 89; Detienne 1979, 25; Cole 1984b, 241, 243; Sourvinou-Inwood 1990, 7 and 1991, 75.

74 At Aesch. Supp. 1003–5, virgins are Aphrodite’s tool to tempt young men.

75 King 1983, 111: the epitaph of Philostrata.

76 Cole 1984b, 243. Aristotle, HA 581b 11–21, claims that young women are particularly wanton during puberty.

77 Lefkowitz 1986, 30, 31, 43 and 48.

78 Perlman 1983, 126, n.61.

79 On the blissfulness of a girl’s childhood compared to the problems entailed by marriage, see Soph. Trach. 144–9; Lefkowitz 1986, 38; Segal, C. 1981, 77 and 84.

80 Lefkowitz 1986, 51; Seaford 1987, 106–7 and 1990, 77–8. Conversely, Antigone is shown to conceive her death in terms of a marriage, Soph. Ant. 891: ω τύμβοβ, ω νυμφείον.

81 Oakley and Sinos 1993, 14–15.

82 For details of the bride’s adornment, see ibid., 16–21.

83 Plut. Lyc. 15.3; De Virt. 4 (245).

84 Bruit Zaidman and Schmitt Pantel 1992, 69; Oakley and Sinos 1993, 34; cf. van Gennep 1960, 141.

85 See Forbes-Irving 1991, 171–94.

86 Cf. Murphy 1972, 57.

87 Vernant 1980, 138, says that female lust causes dysfunctionality because no paternal line of descent can be established for an unmarried woman’s offspring.

88 Cf. Sourvinou–Inwood 1991, 76.

89 Scruton 1986, 27. Cf. Aesch. PV 901–7 where the chorus talk of the consequence of having a divine lover: ούδ’ έχώ ՛ո? αν γενοιμαν.

90 Cf. Burkert 1983, 35; Lefkowitz 1986, 22. Cf., on myths of eating, Vernant 1980, 130–67 and especially 137.

Bibliography