‘Few publications in modern times have excited such curiosity, or produced such extraordinary sensations in fashionable life,’ observed Bell’s Life in London of Harriette Wilson’s Memoirs. ‘It finds its way into all circles, and the grave and the gay – the starched puritan and the professed libertine, are equally sedulous in perusing its pages.’1 ‘Perhaps you may find time to read this trash,’ wrote Poodle Byng, who featured in its pages, to Lord Granville, who featured in them also; ‘not my letter but HW’s Memoirs,’ he added, ‘– Heard of it you must – it has caused sensation here and is almost as much talked of as the Mining Shares … Like most other people I suppose you like to see what is said of your relations …’ Lord Montagu told Sir Walter Scott that the entire Cabinet was reading them because of the mention of one of their members. ‘I am impatient’, Scott replied, ‘to see Harriot Wilsons [sic] biography and have sent an order for it accordingly.’2 The Memoirs were mentioned in Parliament by Dr Stephen Lushington, who complained that the University Club had rejected a request to purchase a Bible for its library while at the same time ordering a copy of Harriette Wilson’s book. A member of the Club replied the following day that although requests for the purchase of the Memoirs had been legion, it had not in fact been bought. Ministers and opposition joined forces to hold emergency meetings at White’s, Brooks’s and the United Service Club, ‘to extinguish this burning shame’, Stockdale imagined, ‘which threatened an extent of desolation which, it was said, would make England not worth living in’.3 ‘But’, Poodle Byng reported to Lord Granville of the crisis in the gentlemen’s clubs, ‘it was determined that nothing in the way of opposition could be done.’4

A notice had appeared in the papers on 6 January announcing the publication the next day of part one of Memoirs, the contents of which were to include ‘The King – Dukes Wellington, Devonshire, Argyll – Marquess of Hertford – Marchionesses of Conyngham, Londonderry – Lords Craven, Melbourne, F. Bentinck, Byron, Proby, Burghersh, Alvanley, Dudley, Palmerston, Lowther, Ponsonby – Ladies Fanny Ponsonby, Berwick, Jersey – Counts Woronzow, Beckendorff, Orloff, Palmella – Honourables F. Lamb, General Walpole, Miss Storer – Sirs John Shelley, James Graham – Generals Mackenzie, Maddan and Lady – Colonels Cotton and Lady, Trench and Lady, Sydenham and Lady – Dr Nevinson – Messrs Sheridan, Beckford, Woodcock and Lady Luttrell, Nugent, Brummell, Mitchell, Ponsonby, Freeling, Graham, Kemble, Young, Eliot, Street, Croker, Murray, Mrs Porter’.5 ‘A pretty list indeed,’ said Brougham on seeing the advertisement. ‘Almost every one of my particular friends is among them!’ Several more of Brougham’s friends were sufficiently threatened by Stockdale’s warning to ensure that this was the last time their names were linked in print with that of Harriette Wilson. Lady Berwick, whose humiliation was immense, tried and failed to prevent further circulation of her sister’s story. It seems, from Harriette’s representation of Sophia, that no money was exchanged, but publication was delayed due to behind-the-scenes negotiations and the first number of Harriette Wilson’s Memoirs did not appear until the following month when the small shop in the Opera Colonnade was teeming with prospective purchasers.

The crowds in and around Stockdale’s premises were so great that he erected a bar outside his door, which was removed only when the final number of Harriette’s book was sold that autumn. Between February and May the Memoirs appeared in nine paper-covered successive parts. The last three instalments appeared in late August bound together in one volume. Publication might have been postponed due to the libel case Stockdale was fighting in July. The instalments included a preface in which Stockdale laid out his own defence: ‘[As] a weekly exposé will guard public morals, spare them not, from the coronet to the counting-house, from the dashing men of fashion, to the sober citizen, from the young and flippant to the sage, sentimental, and hoary sinner’, and continued his attack, ‘It will be seen that this work does not assume to be a complete confession. How much further it may be carried, will probably depend on the reception of what is herein submitted to the public.’

Each instalment sold at 2s 6d, making it cheaper than the serialized editions of Pierce Egan’s Life in London, which had cost three shillings per number four years earlier, but it was still a high price to pay. The cost restricted Harriette’s readership to Byron’s ‘twice two thousand, for whom earth was made’, and it was only later when the price came down that the Memoirs would have been available to a wider market. On the back cover Stockdale listed, in order of rank, the names of those Harriette had included in her story and those who would appear in the future if they did nothing now to prevent it: ‘Dukes. Argyll, Beaufort (and Duchess), de Guiche, Leinster, Wellington. Marquesses. Anglesey, Bath, Headfort, Sligo, Worcester.’ The front cover announced the day and hour on which the next part would be available, but publication was increasingly delayed due to negotiations with significant parties.

Lord Craven, who refused to pay, lived just long enough to see his name emblazoned across Harriette’s opening line. He died, more famous than he might have been, in the summer of 1825. One month after the first instalment appeared, Clanricarde, who also refused to pay, married the only daughter of the Foreign Secretary, George Canning, and began his career as a Canningite Tory. Canning, who had himself been a lover of Harriette’s, had bought her silence.

An illustration by a new artist, Henry Heath, intended as a frontispiece to the Memoirs, was published on 21 February by the radical S. W. Fores of Piccadilly (plate 28). Titled La, Coterie, Debouché, it shows Harriette, fresh and youthful with a crown of red roses in her hair, poised, quill in hand, at a round, cloth-covered table on which sits a large packet of letters, labelled For Future Observation. Twelve admiring swains crowd together before her, each trying to get her attention. Ponsonby is holding a dog; Wellington, in uniform, doffs his cocked hat; Worcester, Yarmouth, George Lamb, Argyll and Canning all rush in to compliment the author; ‘an elegant figure’; ‘what brilliant wit’; ‘the soul of sentiment’; ‘what an expressive countenance’; ‘such smart repartee’.6

Harriette’s Memoirs went through thirty-five editions in the first year alone. While many of these ‘editions’ are not reprintings but unsold sheets bound together with a new title page, there is no doubt that the book sold. Successful translations simultaneously appeared in France, Brussels and Germany. The Age Reviewed reported in 1828 that 50,000 copies of the Memoirs had been sold, but the quantity of piracies produced make the full circulation impossible to calculate.7 Stockdale used at least two printers, and James Barnard, the son of one of them, recalled his father printing off 7,000 copies of the Memoirs; Poplett, another of the printers, was contracted to print 1,000 sheets a week but found that 17,000 sheets were called for.

Stockdale was fighting hard to keep up with the demand for Harriette’s story. ‘Some of its numbers are out of print,’ Bell’s Life wrote, ‘but we understand the publisher is making gigantic efforts to gratify the taste of his customers.’8 The fourth number, Bell’s Life reported on 6 March, appeared only after a ‘long and mysterious delay’. Rumours were afloat that publication was withheld until the Duke of Beaufort and Stockdale had come to an agreement about certain passages. ‘A negotiation was opened,’ thought Bell’s Life, ‘and we understand the offensive matter was withdrawn, and something else substituted upon the trifling consideration of restoring Harriette to the full enjoyment of her bond. We give this as the on dit of the day – it is the topic of general conversation among the lovers of scandal, and may or may not have foundation. It is evident that the present number is by no means so interesting as those which preceded it, and from that fact alone, added to the delay which has taken place, greater confidence is attached to what we have related. Should any more of those little suppressions meet our ear, we shall not fail to include them in our columns.’9 When the fifth number appeared on 9 March, again ‘after considerable delay’, ‘the moment the specified time for delivery arrived, Stockdale’s shop was almost taken by storm. It is rumoured that negotiations have been going on for various suppressions: but to this Stockdale pleads “Not Guilty”. We would rather apprehend, however, that there is good ground for such a belief, and hope to be able to get a peep behind the curtain …’10

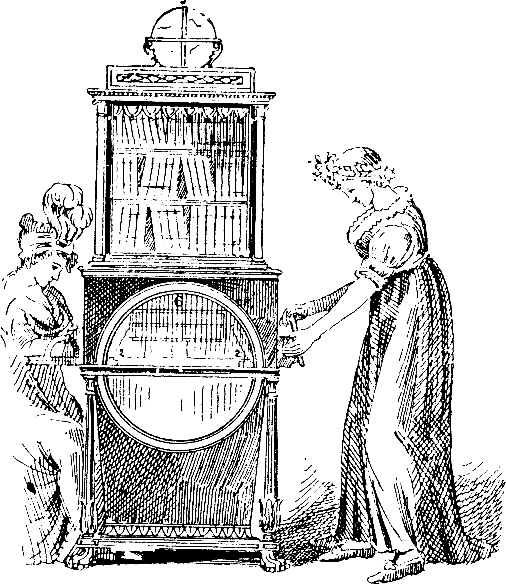

As the regular instalments accumulated, Stockdale brought them out in volumes selling at 7s 6d. The first edition contained twenty-eight coloured plates, which he also sold separately at two shillings, eighteen of which were scenes from the Memoirs. Illustrated books showing real people were extremely rare, so the Memoirs appeared unique. Lorne sits whistling on a gate as he waits for Harriette to appear from her house in Somerstown (plate 13); Frederic Lamb attacks Harriette by the throat (plate 10); Wellington stands in the rain as Argyll, disguised as a duenna, speaks to him from Harriette’s bedroom window (plate 19); Worcester laces Harriette’s stays as he makes toast over the fire for her breakfast (plate 24). The illustrations are comic caricatures, picking up on the satirical humour of the Memoirs. Ten of the plates were reduced copies by George Cruikshank of Richard Dighton’s Characters, at the West End of Town, which illustrated the present state of the gay lotharios whose youths had been immortalized by Harriette. Argyll appeared as stout, bewhiskered and patrician, in a top hat, Worcester as an ageing dandy walking his poodle, and a bloated Lord Alvanley was depicting staggering, as usual, to White’s.

Stockdale’s profit would have been greater had not the populist publishers of the day, such as Onwhyn, Duncombe, Dugdale and Benbow instantly seized on the fact that copyright laws could not protect publications such as Harriette’s. Stockdale’s fears were realized when the first pirated editions – 5,000 copies – were sold at a bargain four shillings. On 11 January 1826, he appeared with Brougham at the King’s Bench to prosecute the publisher, Mr Onwhyn, of Catherine Street in the Strand. This was the only time Stockdale sued for infringement of copyright, and he was hoist by his own petard. Onwhyn’s defence was that, given their ‘licentious, libellous’ nature, the Memoirs could not be defended at all, and he was therefore exempt from prosecution. Stockdale, in a move that does not reflect well on him, had employed this same line in Poplett v. Stockdale on 1 December 1825, when he was taken to court for non-payment of one of his printing bills. ‘No one who has assisted in putting forth such a work to the public,’ the Lord Chief Justice then ruled, ‘can recover for the labour he has employed upon it … He who leant himself to the violation of the laws in his country in this gross and shameful manner, shall not be allowed to claim payment for what he has done in execution of such a criminal purpose.’11 The verdict in both cases was Non Suit, on the grounds that ‘the law cannot recognize as property the history of the low amours of a notorious courtesan’.12 After this judgment, the pirates were safe from all fear of interruption from the law.

Pirated editions were advertised everywhere in the press. Bell’s Life carried an advertisement on 27 March for Duncombe’s ‘verbatim’ ‘Memoirs of Harriette Wilson, the cheapest edition, price 2s. 6d … including her amatory adventures with most of the Nobility of the present day’. ‘Thomas’s edition’ was advertised on 10 April, at eight shillings for the first two volumes. Different styles of illustration appeared in the different editions. In the Memoirs published by Douglas in 1825, Harriette is the heroine of a sentimental novel. In one scene she sits with Ponsonby, the two of them gazing into one another’s eyes, he looks amorous, she looks anxious, he clutches her left hand, her right hand sits demurely on her lap (see illustration to Chapter 10). In another scene, Harriette, in white silk, waits patiently in an elegant room in Brighton while, through the open window, Lord Craven is sailing his boat (see illustration to Chapter 5). There is no sign of the boredom Harriette describes having suffered during this period. Some editions contained semi-pornographic images: Amy, breasts exposed and hair tumbling down, sits on a bed in a state of surprise while William Ponsonby pokes his head through the curtains. Favourite scenes for illustration in all editions were Wellington’s being refused admittance by Argyll to Harriette’s house, Sophia’s dropping her black pudding when she encountered Deerhurst in the street, and Harriette’s being waited on in Brighton by an abject Worcester. In an illustration by Henry Heath for one edition, Harriette sits up in bed while Worcester, in nightcap and nightshirt, makes toast on the fire. ‘Oh Worcester, what a tender and affectionate Husband you will make!!!’ she exclaims. ‘My dearest dear Harriette,’ he answers, ‘this menially waiting upon you is ecstasy in comparison with the Regent’s Music.’ Harriette’s narrative could fit into the comic, pornographic or sentimental, and the type of illustration chosen suited the type of reader being targeted.

Bell’s Life itself reproduced the Memoirs as the instalments appeared and serialized them on its front page between 13 February and 2 October 1825, making no bones about the desire to hurt Stockdale’s sales. Chapbooks of edited highlights appeared and the magistrate of Bow Street gave orders to his officers to ‘apprehend any of those hawkers who should be found vending “The Adventures of Harriette Wilson”’. On 15 March, a penniless apprentice shoemaker was found holding a placard on which was Robert Cruikshank’s caricature of Harriette riding backwards on a black lamb.

Here I am like a W—— as I am

Riding on my black LAMB

Who for my frincum crancum

Have lost my bincum bancum

And for my tail’s game

Have come to this Worldly shame

Which makes the DUKE a public game

And Harlotte Wilson is my name.13

The ‘poor lad,’ an apprentice to an impoverished shoemaker, had been sent out to sell pamphlets called The Whole and Amorous letters from Harriette Wilson to the King, the Duke of Wellington and other noblemen in order to make an ‘honest penny’.14 The magistrate conceded that there was nothing obviously libellous about the placard and agreed that it would be difficult to prosecute ‘this young retailer of a strumpet biographer’ when every bookseller’s shop in London was selling her Memoirs. A letter appeared in The Times and other papers sending up the rich variety of Memoirs on the market: ‘We are delighted to be able to inform our readers on the most undoubted authority, that an edition of the moral and instructive Memoirs of Harriette Wilson, adapted for families and young persons, by the omission of all objectionable passages, which cannot with propriety be read aloud, by the Rev. Thomas Bowdler, FRS, etc, author of the family Shakespeare, is in the press, and the true friends of undefiled morality and our holy religion may shortly expect this previous addition to their libraries.’

Stockdale despaired over the piracies and Harriette wrote to Brougham on 14 July for advice on copyright law. The pirates and the costly libel case Stockdale had lost on 1 July eventually threatened to put a stop to the Memoirs. ‘Respecting the rest of my history,’ Harriette asked Brougham, ‘is it not a crying shame that this great national loss is to be permitted? Six more parts, in manuscript, lie in Stockdale’s desk, a dead loss to him and to the public. Who is to blame? Pirates, shabby lawyers, judge and jury. Oh pray do continue these dear Memoirs, says everybody I meet, saving and excepting the immediate figurantes. We are all so delighted with them, says a formal lady, the wife of a principal character in the book: these vile men, our husbands, have at last got what they deserve. Pray don’t let people buy themselves out and thus destroy the interest of your book. You are such a sweet writer …’15

Stockdale’s reason for bringing out the final three instalments in August as one volume was correctly assumed by Bell’s Life ‘to ensure a few days further delay from piracy, while the publisher can get off a profitable stock’. However, ‘we shall’, Bell’s Life concluded, ‘in two or three of our numbers, dispose of everything really worth notice in this seven and sixpence book’.16

But there was someone else who was also determined to dispose of everything really worth notice in Harriette’s book, and six weeks after the appearance of the first instalments of Harriette’s Memoirs, Julia Johnstone rose from the grave.

*

Harriette, it seems, had fancifully killed her friend off in the way that one does when a character in the plot becomes de trop. According to Harriette, Julia had been in the family vault for the last ten years, but the instalments in which her death was described had not yet been published and so Harriette’s readers did not yet know what cruel blow fate was to deal her unhappy rival. Julia, who was alive and well and living in Hampstead, had heard rumours of her death at Harriette’s hands, ‘for Harriette has industriously circulated through her Pall Mall agents and retailers of her infamy, “that I died in a workhouse and she knows both my executors”.’17 What offended her was not the fact that she was presumed dead but the suggestion that she might have died in such a lowly state. This was not what Julia had planned; if Harriette had indeed believed Julia to be dead, it was because Julia herself put it about that she was.

Julia had cut herself off from Harriette in the aftermath of the Worcester scandal in order to attempt a reconciliation with her family. One of the principal things they insisted on, Julia wrote, ‘was that I should give up all the acquaintance made in my degraded state, before they would extend protection to me or my children; so of course [Harriette] was the first whose society I abandoned. In truth, those who knew me, and the reasons I had for total seclusion from the world, took some pains to convince [Harriette] that I had died in Scotland …’18 Harriette therefore had reason to believe in Julia’s death; it seems that her only embellishment had been her place at Julia’s bedside when she breathed her last. ‘The first number of [Harriette’s] Memoirs, and probably the second, were written by her at the time when she was ignorant that such a one as myself lived to refute her lies. But I had taken care she should now know whether I was dead or alive, and no doubt she actually wished I had long ago vanished from the world’s surface …’19

By the time her Memoirs appeared, Harriette knew that Julia was alive and breathing fire and approached her through an attorney, Charles Hemley, who proposed that she give up all Harriette’s letters and ‘abstain from exposing her’ in exchange for £400. Julia rejected the offer, claiming that she valued her ‘good name more than money’. Julia was actually planning on using her knowledge of Harriette as a means of clearing her own bad name, while making more than £400 in the process; she was badly in need of money. On 25 March, there appeared the first part of Julia Johnstone’s Confessions: In Contradiction to the Fables of Harriette Wilson, published by William Benbow.

Julia started to dictate her Confessions to Benbow shortly after the first instalments of Harriette’s Memoirs had appeared. Having seen only the first three instalments, she had no idea what Harriette was going to say next and therefore what it was that she, Julia, was going to have to confess: this explains the random-fire nature of her ‘narrative’. Contradict everything, just to be on the safe side. Harriette did nothing to edit the account of Julia’s death from the Memoirs. She kept it in to amuse her readers, to avenge herself on her ex-friend, and to discredit what Julia had said in her Confessions.

Just as Harriette’s Memoirs are in part a letter to the Duke of Beaufort, Julia’s Confessions are addressed to the Earl of Carysfort. The reason Julia set out to contradict Harriette’s tale was to redeem herself in the eyes of her uncle. ‘But for these Confessions,’ Julia wrote, her family ‘would have forsaken me as the guilty thing Harriette Wilson made me appear in her Memoirs’.20 Julia means to tell a story of good versus evil and congratulates herself at the close of her book on having been able ‘to acquit my conscience of a heavy debt, on the score of religion and morality. I say with St Paul, “I have fought the good fight – and have finished my course.”’21 Lord Carysfort would also expect Julia to estrange herself from Cotton, with whom, it appears, she had reunited. Cotton had long ago separated from his wife and Julia insists in her Confessions that she had broken with him completely: ‘I have long ago parted, no more to engage with the Colonel; so that I am advocating his cause from no interested motives – nay, probably I am foolishly doing a friendly act to one who laid the foundation of all my misfortunes, and has since treated me with an indifference bordering on inhumanity.’22 It is possible, however, that Julia cut off from the world after 1815 not because she was whitewashing herself but because she did not want it known that she was in fact living with Cotton once more.

If Julia’s domestic situation became known to him, Lord Carysfort would discontinue her allowance, and Julia and Cotton could not afford to lose his money. Poverty had dogged their relationship; Cotton had got into financial trouble back in 1797 through a substantial loan of £8,000 he had made to a bankrupt uncle which had not been repaid.23 It was his subsequent embarrassment that led him to sell his colonelcy in the 10th Dragoons in 1799, and to leave Julia without support during the following years. It was his failure to provide for her in Primrose Cottage that led to Julia leaving Cotton to live with Harriette in Bloomsbury. But Josiah Cotton never stopped loving Julia Storer; Harriette says that he never disappeared from Julia’s life, continuing as her loyal ‘swain’ throughout her years with the three graces. It was not Cotton who tired of her, as Julia would have us believe: she, rather, grew tired of Cotton and was encouraged by Harriette to earn her own keep in the demi-monde. It is this fact of which Julia seems most ashamed in her Confessions, and which she makes most effort to deny.

Julia had another reason to keep her relationship with Cotton a secret from her family: she may have once again given birth. Baptism records of the Old Church at St Pancras, near where she lived, show that in 1823 a child called Julia Storer Johnstone was born to Josiah Johnstone (‘Gentleman’) and Eliza Catherine. The coincidence of names is so striking that it is possible the scribe confused mother with daughter, and that Julia Storer and Josiah Cotton, alias Johnstone, therefore had another child, Eliza Catherine. Julia was forty-six, and had been with Cotton now for thirty years.24

Julia’s Confessions are a bilious attack on Harriette’s supposed dishonesty, with the stated aim of lessening her rival’s sales: ‘My simple explanations have already materially injured the sale of her lying work, the last number not having come up to any of the former in quantity sold, by some thousands: and if my health permitted, and I could write faster, so as to publish a book at once, I would soon drive her totally out of the market.’25 And so the fortnightly appearance of Harriette’s Memoirs was promptly followed by a contradictory instalment from Julia. Every detail of Harriette’s story is challenged. Harriette was never, Julia claims, ‘connected with Lord Ponsonby and never spoke to him above twenty times in her whole life’.26 While waiting for Worcester in Charmouth, Harriette had a child by a soldier; Amy, on the other hand, never had a child by Argyll and nor did Worcester ever propose to Harriette; Fanny was a drunk; Amelia Dubouchet was a ‘shocking vulgar woman, very forward and coarse in her language’;27 the family lived in Hammersmith with Dubouchet maintaining them all on a captain’s commission. The list of Harriette’s supposed fabrications is endless. Throughout the Confessions Julia argues that she was a key player in all the major events in Harriette’s life – that she was listening behind the door when Harriette first met Sir Arthur Wellesley, that she was the confidante of Ponsonby and Worcester, that she accompanied Harriette to Charmouth. It is a further mark of Julia’s confused motivation that in the attempt to dissociate herself from Harriette she writes herself further into her former friend’s life. Ever on the side of the powerful, Julia says that it was she who informed Beaufort of Harriette’s infidelity and that is why he subsequently stopped the annuity and her own relationship with Harriette came to an end. It is, most significantly, Julia who tells us that Harriette sent Wellington a letter asking for ‘£300, threatening in the case of non-compliance to write anathemas against his moral reputation’ and that the Duke returned ‘her letter with “write and be d——d” written in red ink on the back of it’.28 The fact that Julia Johnstone originated the phrase that has gone down in history as ‘publish and be damned’ is evidence enough of her influence on the public. Wellington’s apparent retort being now more or less all that is known about Harriette Wilson suggests that Julia’s Confessions were read by many and assumed to tell the true story. She succeeded in reducing her rival to a catchphrase that confers dignity on Wellington and damns Harriette.

Julia’s Confessions are still treated as the rational corrective to Harriette’s fictions.29 What becomes increasingly apparent, however, about the Memoirs is how accurate much of what Harriette says actually is. She uses dramatic licence to entertain her readers and amuse herself (as in her anecdotes about Byron), dates are chaotic and confused, and important episodes of her life are erased and embellished according to what payments she has received by those who were involved. But, in general, the version of events as Harriette tells them can be borne out by what secondary documentation exists. This is particularly apparent in the Worcester episode. Julia’s story, with the occasional exception, is written so wilfully ‘in contradition’ to Harriette’s, and offers so little other than contradiction, that it might almost be the work of John Mitford, the prolific Regency pornographer, or even of Julia’s own publisher.

There is of course a chance that Julia had indeed died and that William Benbow, wanting to cash in on the success of Harriette’s Memoirs, rushed out an equally scandalous book under Julia Johnstone’s name.30 The case would not be unusual; many courtesans’ memoirs of the time were written by hacks. There are, however, strong arguments against this theory. Firstly, Julia challenges her readers to write to Benbow for her address if in doubt as to her continued existence.31 And among other signs of Julia’s continued existence is a report from the Morning Herald in 1824 that she was found drunk and disorderly on King Street, clad in her ‘silks and satins’.32 Secondly, there is something authentic about the troubled voice of Julia’s Confessions; rather than trying to trump the sauciness of Harriette’s Memoirs, the Confessions are the work of a confused, jealous, disappointed woman. The courtesan, Julia says, ‘breathes pestilence and walks in corruption – her course is that of a crazy and rotten barque, gliding rapidly along a turbulent and impure stream, among rocks and quicksands, where it is prematurely wrecked, or after many weary struggles, is lost in the dark ocean of oblivion’.33 The narrative tone lacks the blandness of most ghost-written revelations. The narrator’s unhappiness is so extreme that she might be thought a one-dimensional creation were it not for variations in her character too subtle for any speed-writing hack to imagine. She is a fallen angel trying to clamber home, she is unconfident, foolish enough not to know that she is dull, too dull to know the difference between her Confessions and Harriette’s Memoirs. She has no understanding of Harriette’s appeal and what she says to lessen her rival’s attractions serves only to enhance them while lessening her own: ‘There are many who read this, will recollect [Harriette’s] riding like a mad woman through the Parks, on a stout cream-coloured charger, with her hair streaming loose in the wind, and her beaver half off, with a servant on a cart horse, in brown livery, toiling after her – she was then upon the wane, like a shop that has ceased to attract customers …’34 Julia gives us a picture of Harriette Wilson aged thirty-eight in which the writer’s competitive malice is tempered by genuine pathos and what begins as mockery ends in elegy.

Imagine to yourself a little woman in a black beaver hat, and long grey cloak … No tightening at the waist to show the figure of the wearer, nor any ornament to be seen what-ever. Her figure, at a short distance, might not inaptly be compared to a milestone with a carter’s hat resting on its summit. Her once little feet, now covered with list shoes to defend them from attacks of a desultory gout which she has suffered long in both extremities. Her face, at the time I allude to, was swollen with this disorder to distortion. She has no colour – le couleur de rose a disparu [sic] – and in its place appears a kind of dingy lilac, which spreads all over her once light countenance, and appears burnt into her lips. The crow’s feet are wide-spreading beneath her eyes, which, though sunken, still gleam with faded lustre through her long dark eyelashes. She bears the remains of what was once superlatively lovely – the wreck of the angel’s visage is yet to be seen; it looks interesting in decay – not the decay brought by age and infirmity, but beauty hurried away prematurely, from the practices of a licentious and dissolute life; such is the once celebrated Miss Dubochet, alias Wilson.35

Newspaper reports confirm the dramatic change in Harriette’s appearance, but only Julia Johnstone could write like this. She is at the same time furious and profoundly embarrassed by Harriette’s Memoirs: ‘I scarcely can show myself abroad.’36 She is doubly humiliated: not only has she been exposed as a courtesan but as a second-rate one at that. Julia’s Confessions attempt the contradictory task of proving that she was never Harriette’s rival because she never sunk so low – ‘I have been no rival demirep of Harriette’s, but attended her as the fabled pilot star does the comet, until it “curbs its red yoke and mingles with the sun”’37 – while being the only courtesan who rose high enough to be able to rival Harriette: ‘The ironical manner in which Miss Wilson speaks of me throughout her Memoirs tells a plain truth, that I was her most successful rival, or [as] she once phrased it, the decoy duck that carried away all her sportsmen.’38 What Julia inadvertently ends up doing is competing over who was the better courtesan. Harriette was, ‘Lord Ponsonby once flatteringly observed to me, “the meteor that dazzled from its borrowed lustre for a time, and then faded away; but … I was the steady planet, a source of never fading attraction, whose vivifying heat was by all acknowledged and felt by all”’.39

William Benbow could not have produced something so psychologically complex. Nor would he have ever written as Julia did about royalty and the aristocracy. The writer of the Confessions is preoccupied above all else with reclaiming her rightful place in the hierarchy; abjection and snobbery dominate the text. Julia sets out to defend the libelled King – ‘the most exalted character in the nation’ – and the other names whose greatness Harriette has attempted to diminish: ‘My book may restore peace into the bosom of many families, from whence it has been driven by the Demon of Discord.’40 It is Julia’s preoccupation with the virtues of the ruling class as against the sins of the demi-monde that presents the strongest argument for its having been her, rather than her publisher, who wrote the Confessions.

Benbow was forty-one, a trained shoemaker, and an active member of the Radical movement, although his politics were far to the left of the Radicals: he belonged to the political underworld; he wanted armed revolution to create a new order. He began his literary career as William Cobbett’s publisher and then moved on to pamphleteering, writing, printing, editing and bookselling. In 1821 he published a series of pamphlets, Crimes of Clergy, attacking the Church of England, which landed him in prison for the second time in his career. He approved of Byron and Shelley and pirated much of their poetry; he railed against Southey, who renounced the radicalism of his youth; he produced editions of Thomas Moore’s works, M. G. Lewis’s The Monk, Henry Brougham’s critique of Byron, and a series of letters from an American Indian in London to his friends back home. Six months before Julia approached him with her Confessions, he had been in the bankruptcy court.41 Benbow had the political vision that Stockdale lacked, which included exposing the sexual hypocrisy of the aristocracy. He was working towards political change while Stockdale was tapping into the Zeitgeist.

Benbow was what Stockdale never managed to be: a man of the people. His publications in 1820–21 captured the public feeling about Queen Caroline, the estranged wife of George IV, and he ended up back in prison for his lampoons of the King. Benbow could not have written, even in jest, the following account of the young Prince of Wales at a ball attended by Julia: ‘His affability, cheering smiles, and restless anxiety to make the party happy, were perfectly captivating. He had something to say to all, and wandered about the ball-room like a fond father among his doating [sic] children. Those who have seen our gracious Prince at such moments when he casts off Majesty and descends to the state of a private gentleman, can never forget the impression he makes on the finer feelings of our nature.’42

It seems at first ironic that it should be Benbow – who challenged the Establishment to which Julia wanted to be reinstated – who published her Confessions. He seems more suitable as the publisher of Harriette’s Memoirs, while Stockdale’s politics have more affinity with Julia’s. While Benbow clearly missed the point of Julia Johnstone, he saw something else in what she had written. Her tale represented the ultimate in the hypocrisy of the aristocracy; Julia was properly displaced, belonging neither to her own family nor to Colonel Cotton’s, neither to the demi-monde nor to the grande-monde. She was the ideal class victim, but this would not have been her only appeal. Benbow approved of courtesans whom he saw as representing physical pleasure, and women’s bodies he thought of as the great class leveller. The fact that the pleasures of Julia’s body were restricted to the aristocracy alone was a fault of the system of limited ownership, and not of the traffic in women. Courtesans should belong to the many and not to the few.

After the publication of her Confessions, there are no further records of Julia Storer. It is not known when, how or where she died, who grieved for her or what became of her children. Even the Proby family tree, complete in all its details, omits Julia’s name and dates, acknowledging only that Elizabeth Storer, née Proby, had a ‘daughter’. Cotton kept his rooms in Hampton Court until his death in 1848. It is unlikely that Julia would have lived there with him, more likely that she died in poverty, her uncle having disowned her once more after the appearance of the Memoirs and Confessions.

*

When the Memoirs were published, both Harriette and Stockdale received a torrent of abusive and anonymous mail; Harriette eventually made it known that she would open nothing that did not contain the sender’s name and seal on the envelope. Beau Brummell, whom she visited in Calais, ‘declared … that my book was infamous, abominable, shocking! And at the last exclamation, he turned up his eyes … What has that truly amiable woman, the Duchess of Beaufort, done, pray? … Abused me most shockingly to begin with, in letters addressed to her son – I replied … The Honourable Berkeley Craven … was equally abusive at being left out of the Memoirs, as was Mr Brummell for having figured in their background. Of course, I mean what I say; nothing more nor less than that Brummell’s very low birth placed him at the bottom of the list of fashionables.’43

But not all of the fashionables were against Harriette Wilson. Mountcharles, previously Lord Francis Conyngham, supposedly enjoyed Harriette’s malice and as long as he was not a part of it he was happy to see anyone else’s behaviour, especially his mother’s, laid bare. Harriette told Brougham that she had been ‘persuaded and encouraged to write the Memoirs by Lord Mountcharles’, and she quoted a letter he had written to her on 1 March 1825 saying how that he hoped ‘that 5 part will soon appear’ and that she was ‘quite mistaken about the Memoirs – my bookseller knowing my eagerness for them sends them me almost before I know they are published – I wish you could get Stockdale to send me one of the contact copies of no. 6’.44

‘Ayes for the Memoirs,’ Harriette noted, ‘His Royal Highness the Duke of York, and I hope, the King, whom I am afraid to begin the page with.’ King George in fact lay on his deathbed two years later cursing her, but the Marquesses of Graham and Hertford (formally Yarmouth), whom she both cited as supporting her, seem more credible candidates, the former having bought himself out and the latter being unashamedly debauched. ‘Of its merits as a literary companion,’ the press reported, ‘men of the first taste have spoken in the most favourable terms; and among others, an eloquent minister of State, in whose library it occupies a conspicuous place.’45 The Foreign Minister, George Canning, who purchased Harriette’s silence, thought them clever. ‘It is impossible but that the work must be delicious scandal,’ Walter Scott wrote, ‘and I will bet on Canning’s side without having seen a letter of it.’46 ‘Even Berkeley Craven and Brummell’, said Harriette, ‘in the midst of their fury, declared to me the Memoirs were excellent, and that they had never heard two opinions on that subject. In short, the ayes are innumerable.’47 Frederick and Charles Bentinck neither bought themselves out nor protested their inclusion. According to Harriette, Charles Bentinck shrugged the whole thing off. ‘We are all in for it … my brother Frederick and I are in the book up to our necks; but we shall only make bad worse by contending against it; for it is not only true, every word of it, but it is excellently written and very amusing.’48 Scott disagreed on these points, arguing that ‘though the attempt at wit is very poor, that at pathos [is] sickening’. What he liked was Harriette’s skill at mimicry. ‘There is some good retailing of conversations, in which the style of the speakers, so far as is known to me, is exactly imitated, and some things told, as said by individuals of each other, which will sound unpleasantly in each other’s ears. I admire the address of Lord A[lvanley], himself very sorrily handled from time to time. Someone asked him if HW had been pretty correct on the whole. “Why, faith,” he replied, “I believe so” – when, raising his eyes, he saw Q[uentin] D[ick], whom the little jilt had treated atrociously – “what concerns the present company always excepted, you know,” added Lord A[lvanely], with infinite presence of mind … After all, HW beats Con Phillips, Anne Bellamy, and all former demireps out and out.’49 ‘Among other confirmations of the genuineness of the pictures’, wrote Bell’s Life, ‘… is that of his Grace the Duke of Wellington, who in a conversation with the Duke of York and the Marquis of Hertford a few days back, candidly admitted that some of the stories representing himself were true.’50

When Harriette Wilson became once more the talk of London it was a very different place to the sleepless city of which she had been crepuscular queen, and this difference was a vital component in the book’s reception. The mood was changing; men who had been proud to be seen with Harriette twenty, or even ten, years before, were ashamed of the connection now. The Radical tailor Francis Place remembered that in the 1780s tradesmen did not care if their daughters became kept mistresses, but in the 1820s it was considered scandalous. ‘A tradesman’s daughter who should misconduct herself’, he wrote, ‘… would be abandoned by her companions, and probably by her parents.’51 By 1825 it was generally accepted that the duty of the husband was to provide for his wife and children, the duty of wives and daughters was to be chaste, and the bonds of matrimony should be not only respected but revered. Middle-class criticism of the domestic lives of the upper classes was reaching its height, and sexual reputation was the focal point of the burgeoning evangelical campaign. The Puritanism that had been increasingly practised by the middle classes was fast spreading upwards. ‘It is a singular satisfaction to me’, wrote the pioneering moralist Hannah More, ‘that I have lived to see such an increase of genuine religion among the higher classes of society.’ Worcester’s mother, the Duchess of Beaufort, was among those who caught the evangelical fever and she withdrew herself and her eight daughters from society.

The shifting mood of the nation was evidenced not only in the public’s support for Queen Charlotte and the pilloring of the loathed King, but in the response to Byron’s death in the spring of 1824. Initially mourned as a national hero, Byron was fast becoming the scapegoat for all that was considered decadent and debauched in the Regency, and approving of him was tantamount to devil worship. ‘Many make the sign of the cross at the mention of his mere name,’ wrote the German rake and traveller, Prince Pückler-Muskau.52 After ten years away, Pückler-Muskau returned to the city in 1826 to find it now a ‘seat of Government … and not an immeasurable metropolis of “shop keepers”.’ But he thought this one of the only improvements. ‘London is now so utterly dead as to elegance and fashion, that one hardly meets an equipage; and nothing remains of the “beau monde” but a few ambassadors.’53 The ‘sublime Exclusives’ of this new age were ‘nothing more than … bad, flat, dull impression[s] of a “roué” of the Regency’.54

Newspaper editors were in general united in vilifying Harriette and her publisher, regardless of how much they exploited the pair in order to sell more papers. Stockdale wrote of ‘a conspiracy, formed at the beck of an unmasked aristocracy, and disgracefully, servilely, embraced, by even the boasted, independent press of the self-constituted, moral metropolis, of this moral United Kingdom in this Bible-age of sanctity, to put down the humble publisher who has dared to strip vice of its fascinating mask and exhibit the monster in all its native deformity, even though it had taken refuge in the highest places!’55 ‘The whole weight of the press,’ he further argued, ‘being thown into the scale of the pirates, may be accounted for on the score of interest, as if I had succeeded against Onwhyn [the publisher who first pirated the Memoirs], I must also have succeeded against the proprietors of the newspapers, every one of which had pirated the Memoirs, however they might abuse them, and me.’56

At the forefront of the campaign against Stockdale was the British Lion, a Sunday paper that ran for only a few months in 1825, almost for the purpose, Stockdale believed, of ruining him. ‘Let all the individuals who are libelled,’ the paper’s editor wrote, ‘and whose purses can bear the outlay, put him to the expense of law proceedings … really, some combined effort on the part of those who are in a situation to make it, is due to themselves and the public – to the great cause of National Morals and Domestic Peace … We … implore those who have the power, to come forward and crush this female pest, and thereby read a lesson to hireling publishers, which, to the permanent advantage of society, they will never forget.’57 This battle cry worked. ‘One sapient resolution’, Stockdale wrote of the paper’s attempts to curb circulation of the book, ‘was that they should not buy these Memoirs; but the private curiosity of each to see what figure his companions cut, rendered that resolve nugatory in a moment. Another resolution was to withdraw all custom from the publisher, and discountenance and annoy him in every possible way, especially by actions of law against him.’58 ‘The whole and sole conduct of the editors’, Stockdale reflected later in the year, ‘may be defined in one word, selfishness. Their private pecuniary interest, and that alone, influenced their proceedings. They, one and all, expected to derive pecuniary advantage from the conduct they adopted in regard to these Memoirs, and, while many of them were abusing her, for having endeavoured to get money by her work, their single object was the very same …’59

Harriette Wilson continued to be frequently discussed in the press. The editor of The Times, ‘in a paragraph of, at least, a foot long, with true, genuine, manly dignity loads me, a female, who never injured him, nor meant him harm, with the coarsest abuse, bestowing on me the most gentlemanlike epithets! … I am sorry’, she continued, ‘he has worked himself up into such a desperately vengeful fit against me because really, when I, in the first volume, mentioned Sophie’s porkman having wrapped her black-pudding with a piece of dirty Times newspaper, I never thought of calling its editor a dirty fellow …’ The editor’s outrage increased her circulation rather than putting a stop to it, Harriette reasoned. ‘There were, no doubt, thousands of young ladies who had neither read [my book] nor dreamt of reading it, when this paragraph of the kind and judicious editor, like the apple upon Eve, so worked upon their imagination and excited their curiosity.’ He was a coward, she said, for ‘loading with abuse a female like me, whose only proprietor resides on the continent’ and for never applying ‘those same epithets to Lady Caroline Lamb, nor, in short to any lady whose husband happened to be at hand … what can be more immoral than Lady Caroline Lamb, a wife and mother, publishing her own desperate love letters to Lord Byron, written under her husband’s own roof?’60

On the morning of Tuesday, 15 March 1825 the following letter appeared in the Morning Chronicle:

MR EDITOR – In this age of Memoirs, Recollections, and Reminiscences, it is not to be wondered at that Old Harriette Wilson has been as successful as her neighbours … in gulling the public. From all she or her Ambrosial Friend has written for her one might be led to believe her, when she states such broad facts, in spite of her omitting dates, but with any of our wits about us, we can never forget that people not contemporary could not hold converse; – you must see I allude to bringing the Marquess of Lorne and the Duke of Wellington together, though there were eight years difference between those titles. Poor Tom Sheridan’s account of his father must be equally untrue as it is malicious, from the known fact of the father and son being both taken from us within a few weeks of each other. If this Lady’s Memoirs had been complete, she perhaps might have recollected a little dirty girl, whose name was Du Bouchet, who was five and twenty years ago a regular tramp in St James’s Street, and the courts adjoining, being picked up by a nobleman and converted into a lady; after growing too old for any success in begging from those persons of high rank, whose names she could collect from the Court Guide (her constant practice), she liberated a prisoner from the Fleet, and set him sailing after his pretensions to an Irish Peerage; if she should see this, she will know who wrote it, and perhaps I may receive a round sum not to say any more. She formerly got her living by mending and cleaning silk stockings, at which she was very expert – she was never handsome, though she had good eyes, but was hog backed, narrow chested, and had an awkward shuffling gait, and was not at all like the handsome portrait which is published as that of Harriette Wilson; but this can be of no consequence now, as she must be next summer in her 42d year. But what am I who can recollect such things? Why,

AN OLD RAKE

South Moulton Street, Grosvenor Square.61

This ‘Old Rake’ knew more about Harriette’s past life than most of the scandalmongers of the last ten years who claimed to be authorities, but his suggestion that the Memoirs were written by her ‘Ambrosial Friend’ was based on nothing more than current gossip. The next day, a letter appeared in the paper from an S. Bertie Ambrose, who identified himself as the ghost-writer alluded to, denying that he had anything to do with the authorship of Harriette’s book.

Captain Ambrose had known Rochfort from his days in India when they were in the same regiment. He had since spread the word, Harriette said, that he had been one of her lovers. ‘The fact is’, Ambrose supposedly told her, ‘that knowing you is such a feather in a man’s cap that I could not resist saying I had the honour.’ In a letter to Sophie Stockdale, following an attack on him in the press by Ambrose, Stockdale reminded her, ‘It was Ambrose you know who first gave out that he was the author of Harriette Wilson’s Memoirs, and when they were threatened with prosecution, inserted a letter in the newspapers denying them and afterwards, being asked by Rochfort which lie he would now chose to abide by, confessed that he had nothing to do with them; but treated the whole as a good joke!’62 The rumour that Ambrose was the author of Harriette’s book continued to be treated as a fact for several years.63

Popular prints were only occasionally more sympathetic to Harriette than the newspapers. One caricature, titled Cupid conducting the Three Graces to the Temple of Love, published by King in March 1825, shows Wellington, Sir Frederic Beauclerk and the Duke of Argyll arm in arm, dramatically striding to Harriette’s house. She calls out of the window, ‘One at a time please gentlemen and I am not afraid of twice as many.’ Wellington, as always in full regalia, says, ‘She is a fine girl I assure you and I declare she has run more in my mind than Spaniards Russians or French, if this guide leads us into an ambush I’ll have him hanged.’ Argyll, in Highland costume, says, ‘Eh Lord Sirs there she is and as bonny a lassy as there’s in a-Britain including Argyleshire, I am thinking you twa had better stay where you are till I come back again, as I am an unco judge of the premises.’ Beauclerk, in his parson’s apparel, says, ‘I hope I have too much good manners to refuse seeing a pretty girl and though I belong to the church I don’t think she will find much cant about me.’ A print by Robert Cruikshank called The Flat Catcher and the Rat Catcher, published by Fairburn in February 1825, showed Harriette looking elegant and triumphant in an evening gown standing with Wellington, who looks ridiculous in uniform, in a room surrounded with portraits of figures from her Memoirs. ‘I understand’, Harriette tells her guest, ‘they are going to hang you, who would suppose such a thing could beat Napoleon! I declare you look exactly like a ratcatcher.’ ‘Eh? – What? – I never heard a word of it before,’ Wellington replies. He is dripping with rats (there is a rat in the place of the sheep on his Order of the Golden Fleece, another on his ribbon and one on his tail coat). The Portraits behind them are arranged alphabetically. Duke of A[rgyll], Marquis B, Earl of C[raven], Viscount D[eerhurst], Lord E[brington], Sir – F. Lambskin Pinxit [Fred Lamb], Honourable Mr G[eorge Lamb] and so on. Harriette is the dignified figure in this case, and her lovers look like cowards.

In April, Fairburn published the print of a coloured engraving called The Ducking Stool – A Punishment for Fornication. Or – the Dukes and the Dons shewing up Harriette Wilson. Harriette is tied to a chair which is suspended by a pole above a pond. Holding the pole are Frederic Beauclerk, Wellington, Argyll and Lamb, who each exclaim against her. ‘Go home and mind your wives and don’t persecute me you set of Nincumpoops!’ Harriette calls. ‘I’ll expose ye all in the next volume – I appeal to John Bull to protect me from your violence.’ John Bull, pictured as an affable chap in smock and gaiters, turns to the four persecutors and says, ‘Ye ought to be ashamed of yourselves! First to seduce the poor wretch, and then to ill use her, I think if you had what you deserve it would be the ducking pond instead of her! By Goles if I hant half a mind to give you all a good wapping!!’ The men standing around John Bull cheer him on.

Harriette remained in Paris during the furore generated by her revelations. She was busy all summer writing further instalments and their attendant letters, while Stockdale, who had the manuscript with him in London, scored through those passages of her book which had been bought out.

Notes

1 Bell’s Life in London, 6 March 1825.

2 H. J. C. Grierson (ed.), The Letters of Sir Walter Scott, London: Constable and Co., 1935, vol. IX: 1825–1826, p. 7.

3 Memoirs 1831, vol. 4, p. 302.

4 Quoted in Angela Thirkell, The Fortunes of Harriette: The Surprising Career of Harriette Wilson, p. 216.

5 Morning Chronicle, 7 January 1825.

6 British Museum Print Room, 14828.

7 Robert Montgomery [attrib.], The Age Reviewed, 2nd edn, London: 1828.

8 Bell’s Life in London, 20 February 1825.

9 Ibid., 6 March 1825.

10 Ibid., 13 March 1825.

11 Ibid., 4 December 1824.

12 Trowbridge H. Ford, Henry Brougham and His World, Chichester: Barry Rose, 1995, p. 396.

13 British Museum Print Room, 14831.

14 Bell’s Life in London, 20 March 1825.

15 Memoirs 1831, vol. 7, pp. 327–8.

16 Bell’s Life in London, 28 August 1825.

17 Confessions, p. 1.

18 Ibid., p. 156.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid., p. 284.

21 Ibid., p. 353.

22 Ibid., p. 20.

23 The Public Record Office in Kew holds various documents relating to the bankruptcy of Colonel Cotton’s uncle, John Cotton, of Broad Street, in the city of London, Merchant, Dealer and Chapman (B3/818,819, 820). He was in financial trouble in 1796, 1799, 1804, 1812, 1817, 1821 and 1824.

24 There is no knowing how long Julia continued to live with Cotton. He kept his rooms at Hampton Court until his death in 1848.

25 Confessions, p. 154.

26 Ibid., p. 139.

27 Ibid., p. 104.

28 Ibid., p. 213.

29 Valerie Grosvenor Myer and Angela Thirkell assume that Julia was correcting Harriette’s fictions.

30 I have found no record of her death and she was certainly not buried in the family vault, as Harriette writes.

31 Confessions, p. 154.

32 John Wight, Mornings at Bow Street, London: Charles Baldwyn, 1824, p. 38.

33 Confessions, p. 97.

34 Ibid., p. 177.

35 Ibid., p. 93.

36 Ibid., p. 320.

37 Ibid., p. 353.

38 Ibid., p. 76.

39 Ibid.

40 Ibid., p. 6.

41 See The Times, 6 October 1824 and 9 October 1824, p. 3, col. d.

42 Confessions, p. 78.

43 Memoirs 1831, vol. 7, pp. 328–9.

44 Brougham: 14,535.

45 Bell’s Life in London, 6 March 1825.

46 Sir Walter Scott to Lord Montagu, 18 February 1825; Grierson, op. cit.

47 Memoirs 1831, vol. 7, p. 304.

48 Ibid., vol. 5, p. 259.

49 J. G. Lockhart, Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Paris: Baudry’s European Library, 1838, vol. 3, pp. 337–8.

50 Bell’s Life in London, 6 March 1825.

51 The Autobiography of Francis Place, p. 81.

52 Prince Pückler-Muskau, A Regency Visitor: The English Tour of Prince Pückler-Muskau Described in his Letters, 1826–1828, London: Collins, 1957, p. 26. The treatment of Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, is also worth considering. Her loose lifestyle had not stood in the way of her becoming British Ambassadress to Naples in 1805, but she was rejected by the nation following Nelson’s death.

53 Ibid., p. 38.

54 Ibid., p. 335.

55 Memoirs 1831, vol. 5, p. 21.

56 Ibid., p. 72.

57 British Lion, 24 April 1825.

58 Memoirs 1831, vol. 4, p. 302.

59 Ibid., p. 300.

60 Ibid., p. 295.

61 Bell’s Life in London, 20 March 1825.

62 Memoirs 1831, vol. 6, p. 271.

63 When Harriette saw the ‘Old Rake’s’ letter in the Morning Chronicle, sent on to her by Stockdale in a package containing all the latest ‘newspaper abuse’, she said, ‘I have twice spoken to that gentleman [Ambrose] in the course of my life, knew nothing about him, and cared nothing; but I thought him clever, and spoke of him as such to others.’ Harriette and Ambrose were either being honest about their slight acquaintance or Ambrose had bought himself out of the Memoirs with a hefty sum; Harriette put him on her list of those who were to be exposed in her future Memoirs unless they paid up.