Chapter 5. Data

Data is an extremely broad term, only slightly less vague than the nearly all-encompassing information. What is data? (What isn’t data?) What kinds of data are there, and what can we use with D3?

Broadly speaking, data is structured information with potential for meaning.

In the context of programming for visualization, data is stored in a digital file, typically in either text or binary form. Of course, potentially every piece of digital ephemera may be considered “data”—not just text, but bits and bytes representing images, audio, video, databases, streams, models, archives, and anything else.

Within the scope of D3 and browser-based visualization, however, we will limit ourselves to text-based data. That is, anything that can be represented as numbers and strings of alpha characters. If you can get your data into a .txt plain text file, a .csv comma-separated value file, or a .json JSON document, then you can use it with D3.

Whatever your data, it can’t be made useful and visual until it is attached to something. In D3 lingo, the data must be bound to elements within the page. Let’s address how to create new page elements first. Then attaching data to those elements will be a cinch.

Generating Page Elements

Typically, when using D3 to generate new DOM elements, the new elements

will be circles, rectangles, or other visual forms that represent your

data. But to avoid confusing matters, we’ll start with a simple example

and create a lowly p paragraph element.

Begin by creating a new document with our simple HTML template from the last chapter. You can find it in the sample code files as 01_empty_page_template.html, and it looks like the following code. (Eagle-eyed viewers will notice that I’ve modified the src path here due to work with the directory structure of the code samples. If that doesn’t mean anything to you, don’t worry about it.)

<!DOCTYPE html><htmllang="en"><head><metacharset="utf-8"><title>D3 Page Template</title><scripttype="text/javascript"src="../d3/d3.v3.js"></script></head><body><scripttype="text/javascript">// Your beautiful D3 code will go here</script></body></html>

Open that page in your web browser. Make sure you’re accessing the page via your local web server, as we discussed in Chapter 4. So the URL in your browser’s location bar should look something like this:

http://localhost:8888/d3-book/chapter_05/01_empty_page_template.html

If not viewed through a web server, the URL path will start with file:/// instead of http://. Confirm that the URL does not look like this:

file:///…/d3-book/chapter_05/01_empty_page_template.html

Once you’re viewing the page, pop open the web inspector. (As a reminder, see Developer Tools on how to do that.) You should see an empty web page, with the DOM contents shown in Figure 5-1.

Back in your text editor, replace the comment between the script tags

with:

d3.select("body").append("p").text("New paragraph!");

Save and refresh, and voilà! There is text in the formerly empty browser window, and the web inspector will look like Figure 5-2.

See the difference? Now in the DOM, there is a new paragraph element that was generated on the fly! This might not be exciting yet, but you will soon use a similar technique to dynamically generate tens or hundreds of elements, each one corresponding to a piece of your dataset.

Let’s walk through what just happened. (You can follow along with 02_new_element.html.) To understand that first line of D3 code, you must first meet your new best friend, chain syntax.

Chaining Methods

D3 smartly employs a technique called chain syntax, which you might recognize from jQuery. By “chaining” methods together with periods, you can perform several actions in a single line of code. It can be fast and easy, but it’s important to understand how it works, to save yourself hours of debugging headaches later.

By the way, functions and methods are just two different words for the same concept: a chunk of code that accepts an argument as input, performs some action, and returns some other information as output.

The following code:

d3.select("body").append("p").text("New paragraph!");

might look like a big mess, especially if you’re new to programming. So the first thing to know is that JavaScript, like HTML, doesn’t care about whitespace and line breaks, so you can put each method on its own line for legibility:

d3.select("body").append("p").text("New paragraph!");

Both I and your optometrist highly recommend putting each method on its own indented line. But programmers have their own coding style; use whatever indents, line breaks, and whitespace (tabs or spaces) are most legible for you.

One Link at a Time

Let’s deconstruct each line in this chain of code:

-

d3 - References the D3 object, so we can access its methods. Our D3 adventure begins here.

-

.select("body") -

Give the

select()method a CSS selector as input, and it will return a reference to the first element in the DOM that matches. (UseselectAll()when you need more than one element.) In this case, we just want thebodyof the document, so a reference tobodyis handed off to the next method in our chain. -

.append("p") -

append()creates whatever new DOM element you specify and appends it to the end (but just inside) of whatever selection it’s acting on. In our case, we want to create a newpwithin thebody. We specified"p"as the input argument, but this method also sees the reference tobodythat was passed down the chain from theselect()method. So an emptypparagraph is appended to thebody. Finally,append()hands off a reference to the new element it just created. -

.text("New paragraph!") -

text()takes a string and inserts it between the opening and closing tags of the current selection. Because the previous method passed down a reference to our newp, this code just inserts the new text between<p>and</p>. (In cases where there is existing content, it will be overwritten.) -

; - The all-important semicolon indicates the end of this line of code. Chain over.

The Hand-off

Many, but not all, D3 methods return a selection (actually, a reference to a selection), which enables this handy technique of method chaining. Typically, a method returns a reference to the element that it just acted on, but not always.

So remember this: when chaining methods, order matters. The output type of one method has to match the input type expected by the next method in the chain. If adjacent inputs and outputs are mismatched, the hand-off will function more like a dropped baton in a middle-school relay race.

When sussing out what each function expects and returns, the API reference is your friend. It contains detailed information on each method, including whether or not it returns a selection.

Going Chainless

Our sample code could be rewritten without chain syntax:

varbody=d3.select("body");varp=body.append("p");p.text("New paragraph!");

Ugh! What a mess. Yet there will be times you need to break the chain, such as when you are calling so many functions that it doesn’t make sense to string them all together. Or just because you want to organize your code in a way that makes more sense to you.

Now that you know how to generate new page elements with D3, it’s time to attach data to them.

Binding Data

What is binding, and why would I want to do it to my data?

Data visualization is a process of mapping data to visuals. Data in, visual properties out. Maybe bigger numbers make taller bars, or special categories trigger brighter colors. The mapping rules are up to you.

With D3, we bind our data input values to elements in the DOM. Binding is like “attaching” or associating data to specific elements, so that later you can reference those values to apply mapping rules. Without the binding step, we have a bunch of data-less, unmappable DOM elements. No one wants that.

In a Bind

We use D3’s

selection.data()

method to bind data to DOM elements. But there are two things we need in

place first, before we can bind data:

- The data

- A selection of DOM elements

Let’s tackle these one at a time.

Data

D3 is smart about handling different kinds of data, so it will accept practically any array of numbers, strings, or objects (themselves containing other arrays or key/value pairs). It can handle JSON (and GeoJSON) gracefully, and even has a built-in method to help you load in CSV files.

But to keep things simple, for now we will start with a boring array of five numbers. Here is our sample dataset:

vardataset=[5,10,15,20,25];

If you’re feeling adventurous, or already have some data in CSV or JSON format that you want to play with, here’s how to do that. Otherwise, just skip ahead to Please Make Your Selection.

Loading CSV data

CSV stands for comma-separated values. A CSV data file might look something like this:

Food,Deliciousness Apples,9 Green Beans,5 Egg Salad Sandwich,4 Cookies,10 Vegemite,0.2 Burrito,7

Each line in the file has the same number of values (two, in this case), and values are separated by a comma. The first line in the file often serves as a header, providing names for each of the “columns” of data.

If you have data in an Excel file, it probably follows a similar structure of rows and columns. To get that data into D3, open it in Excel, then choose Save as… and select CSV as the file type.

If we saved the preceding CSV data into a file called food.csv, then we could load the file into D3 by using the d3.csv() method:

d3.csv("food.csv",function(data){console.log(data);});

csv() takes two arguments: a string representing the path of the CSV file to load in, and an anonymous function, to be used as a callback function. The callback function is “called” only after the CSV file has been loaded into memory. So you can be sure that, by the time the callback is called, d3.csv() is done executing.

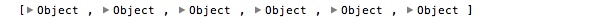

When called, the anonymous function is handed the result of the CSV

loading and parsing process; that is, the data. Here I’m naming it

data, but this could be called whatever you like. You should use this

callback function to do all the things you can do only after the data

has been loaded. In the preceding example, we are just logging the value of

the data array to the console, to verify it, as shown in Figure 5-3. (See

03_csv_loading_example.html in the example code.)

You can see that data is an array (because of the hard brackets []

on either end) with six elements, each of which is an object. By

toggling the disclosure triangles next to each object, we can see their

values (see Figure 5-4).

Aha! Each object has both a Food property and a Deliciousness

property, the values of which correspond to the values in our CSV!

(There is also a third property, __proto__, but that has to do with

how JavaScript handles objects, and you can ignore it for now.) D3 has

employed the first row of the CSV for property names, and subsequent

rows for values. You might not realize it, but this just saved you a lot

of time.

One more thing to note is that each value from the CSV is stored as a

string, even the numbers. (You can tell because 9 is surrounded by

quotation marks, as in "9" and not simply 9.) This could cause

unexpected behavior later, if you try to reference your data as a

numeric value but it is still typed as a string.

Verifying your data is a great use of the csv() callback function, but

typically this is where you’d call other functions that construct the

visualization, now that the data is available, as in:

vardataset;//Declare global vard3.csv("food.csv",function(data){//Hand CSV data off to global var,//so it's accessible later.dataset=data;//Call some other functions that//generate your visualization, e.g.:generateVisualization();makeAwesomeCharts();makeEvenAwesomerCharts();thankAwardsCommittee();});

One more tip: if you have tab-separated data in a TSV file, try the

d3.tsv() method, which otherwise behaves exactly as the preceding method.

Loading JSON data

We’ll spend more time talking about JSON later, but for now, all you need

to know is that the d3.json() method works the same way as csv().

Load your JSON data in this way:

d3.json("waterfallVelocities.json",function(json){console.log(json);//Log output to console});

Here, I’ve named the parsed output json, but it could be called data

or whatever you like.

Please Make Your Selection

The data is ready to go. As a reminder, we are working with this simple array:

vardataset=[5,10,15,20,25];

Now you need to decide what to select. That is, what elements will your data be associated with? Again, let’s keep it super simple and say that we want to make a new paragraph for each value in the dataset. So you might imagine something like this would be helpful:

d3.select("body").selectAll("p")

and you’d be right, but there’s a catch: the paragraphs we want to select don’t exist yet. And this gets at one of the most common points of confusion with D3: how can we select elements that don’t yet exist? Bear with me, as the answer might require bending your mind a bit.

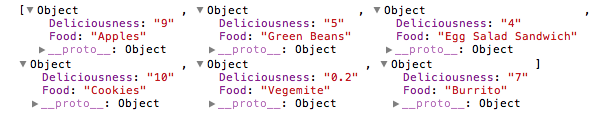

The answer lies with enter(), a truly magical method. See this code,

which I’ll explain:

d3.select("body").selectAll("p").data(dataset).enter().append("p").text("New paragraph!");

View the example code 04_creating_paragraphs.html and you should see five new paragraphs, each with the same content, as shown in Figure 5-5.

Here’s what’s happening:

-

d3.select("body") -

Finds the

bodyin the DOM and hands off a reference to the next step in the chain. -

.selectAll("p") - Selects all paragraphs in the DOM. Because none exist yet, this returns an empty selection. Think of this empty selection as representing the paragraphs that will soon exist.

-

.data(dataset) -

Counts and parses our data values. There are five

values in our array called

dataset, so everything past this point is executed five times, once for each value. -

.enter() -

To create new, data-bound elements, you must use

enter(). This method looks at the current DOM selection, and then at the data being handed to it. If there are more data values than corresponding DOM elements, thenenter()creates a new placeholder element on which you can work your magic. It then hands off a reference to this new placeholder to the next step in the chain. -

.append("p") -

Takes the empty placeholder selection created by

enter()and appends apelement into the DOM. Hooray! Then it hands off a reference to the element it just created to the next step in the chain. -

.text("New paragraph!") -

Takes the reference to the newly created

pand inserts a text value.

Bound and Determined

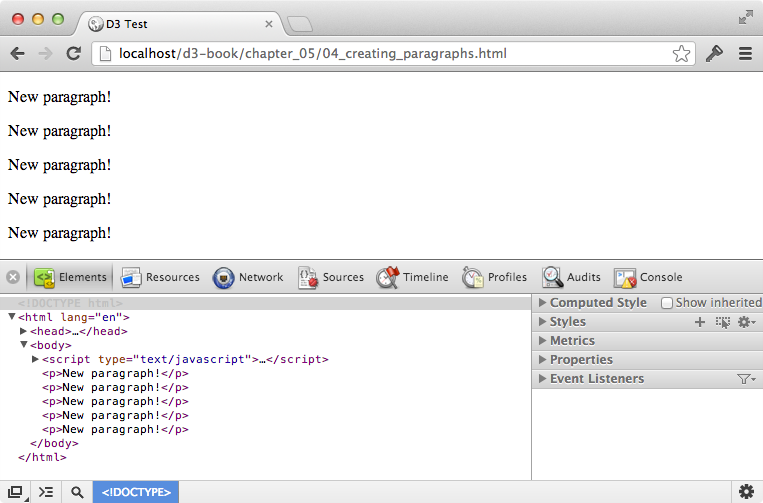

All right! Our data has been read, parsed, and bound to new p elements

that we created in the DOM. Don’t believe me? Take another look at

04_creating_paragraphs.html and whip out your web inspector, shown in Figure 5-6.

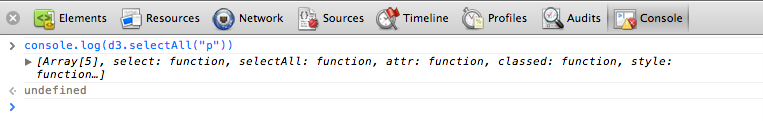

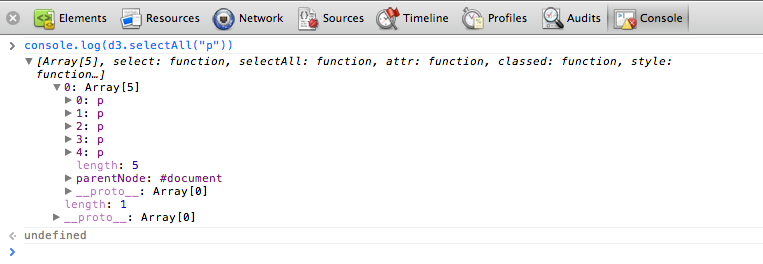

Okay, I see five paragraphs, but where’s the data? Switch to the JavaScript console, type in the following code, and click Enter. The results are shown in Figure 5-7:

console.log(d3.selectAll("p"))

An array! Or, really, an array containing another array. Click the gray disclosure triangle to reveal its contents, shown in Figure 5-8.

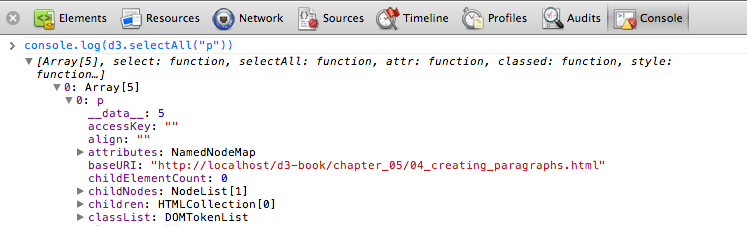

You’ll notice the five ps, numbered 0 through 4.

Click the disclosure triangle next to the first one (number zero), which results in the view shown in Figure 5-9.

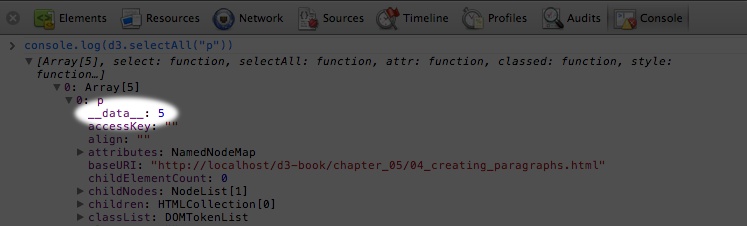

See it? Do you see it? I can barely contain myself. There it is (Figure 5-10).

Our first data value, the number 5, is showing up under the first

paragraph’s __data__ attribute. Click into the other paragraph

elements, and you’ll see they also contain __data__ values: 10, 15,

20, and 25, just as we specified.

You see, when D3 binds data to an element, that data doesn’t exist in

the DOM, but it does exist in memory as a __data__ attribute of that

element. And the console is where you can go to confirm whether or not

your data was bound as expected.

Using Your Data

We can see that the data has been loaded into the page and is bound to our newly created elements in the DOM, but can we use it? Here’s our code so far:

vardataset=[5,10,15,20,25];d3.select("body").selectAll("p").data(dataset).enter().append("p").text("New paragraph!");

Let’s change the last line to:

.text(function(d){returnd;});

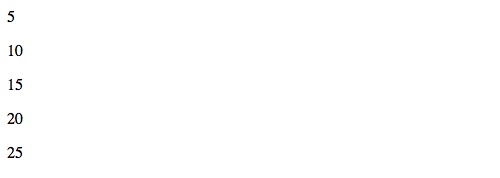

Now test out that new code in 05_creating_paragraphs_text.html. You should see the result shown in Figure 5-11.

Whoa! We used our data to populate the contents of each paragraph, all

thanks to the magic of the data() method. You see, when chaining

methods together, anytime after you call data(), you can create an

anonymous function that accepts d as input. The magical data()

method ensures that d is set to the corresponding value in your

original dataset, given the current element at hand.

The value of “the current element” changes over time as D3 loops through

each element. For example, when looping through the third time, our code

creates the third p tag, and d will correspond to the third value in

our dataset (or dataset[2]). So the third paragraph gets text content

of “15”.

High-Functioning

In case you’re new to writing your own functions (a.k.a. methods), the basic structure of a function definition is:

function(input_value){//Calculate something herereturnoutput_value;}

The function we used earlier is dead simple, nothing fancy:

function(d){returnd;}

This is called an anonymous function, because it doesn’t have a name. Contrast that with a function that’s stored in a variable, which is a named function:

vardoSomething=function(){//Code to do something here};

We’ll write lots of anonymous functions when using D3. They are the key to accessing individual data values and calculating dynamic properties.

This particular anonymous function is wrapped within D3’s text() function. So our anonymous function is executed first. Then its result is handed off to text(). Then text() finally works its magic (by inserting its input argument as text within the selected DOM element):

.text(function(d){returnd;});

But we can (and will) get much fancier because you can customize these functions any way you like. Yes, this is both the pleasure and pain of writing your own JavaScript. Maybe you’d like to add some extra text, as in:

.text(function(d){return"I can count up to "+d;});

which produces the result shown in Figure 5-12, as seen in example file 06_creating_paragraphs_counting.html.

Data Wants to Be Held

You might be wondering why you have to write out function(d) { … }

instead of just d on its own. For example, this won’t work:

.text("I can count up to "+d);

In this context, without wrapping d in an anonymous function, d has

no value. Think of d as a lonely little placeholder value that just

needs a warm, containing hug from a kind, caring function’s parentheses.

(Extending this metaphor further, yes, it is creepy that the hug is

being given by an anonymous function, but that only confuses matters.)

Here is d being held gently and appropriately by a function:

.text(function(d){// <-- Note tender embrace at leftreturn"I can count up to "+d;});

The reason for this syntax is that .text(), attr(), and many other

D3 methods can take a function as an argument. For example, text() can

take either simply a static string of text as an argument:

.text("someString")

or the result of a function:

.text(someFunction())// Presumably, someFunction() would return a string

or an anonymous function itself can be the argument, such as when you write:

.text(function(d){returnd;})

Here, you are defining an anonymous function. If D3 sees a function there, it will call that function, while handing off the current datum d as the function’s argument. Here, I’ve named the argument d just by convention. You could call it datum or info or whatever you like. All D3 is looking for is any argument name, into which it can pass the current datum. Throughout this book, we’ll use d because it is concise and familiar from many of the other D3 examples found online.

In any case, without that function in place, D3 couldn’t relay the current data value. Without an anonymous function and its argument there to receive the value of d, D3 could get confused and even start crying. (D3 is more emotional than you’d expect.)

At first, this might seem silly and like a lot of extra work to just get at d, but the value of this approach will become clear as we work on more complex pieces.

Beyond Text

Things get a lot more interesting when we explore D3’s other methods,

like attr() and style(), which allow us to set HTML attributes and

CSS properties on selections, respectively.

For example, adding one more line to our code:

.style("color","red");

produces the result shown in Figure 5-13, as seen in 07_creating_paragraphs_with_style.html.

All the text is now red; big deal. But we could use a custom function to make the text red only if the current datum exceeds a certain threshold. So we revise that last line to use a function instead of a string:

.style("color",function(d){if(d>15){//Threshold of 15return"red";}else{return"black";}});

See the resulting change, displayed in Figure 5-14, in 08_creating_paragraphs_with_style_functions.html.

Notice how the first three lines are black, but once d exceeds the

arbitrary threshold of 15, the text turns red.

Okay, we’ve got data loaded in, and dynamically created DOM elements bound to that data. I’d say we’re ready to start drawing with data!