THE SEVENTEENTH TO NINETEENTH CENTURIES saw the beginnings of powerful political democratization, as privileges and rights were extended to an ever-broader segment of the population. The kings and the landed class, who had ruled throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, felt their previously tight grip on the reins of power slowly begin to slip away. Political rhetoric, armed rebellion, and wars of independence were the means of recrafting society and its institutions. The idea that society could be imagined anew became an invigorating source of human empowerment.

It is this political democratization that receives most of the ink of history, but there was another democratization afoot—an economic and financial one—that is often missed. The democratization of investment—specifically the expansion of the ability of those who were not members of the elite to participate in the enterprise of investment—had more subtle origins than its political counterpart. Revolutions, social and religious upheaval, and new political philosophies begat political democratization, but the democratization of investment was rooted in three crucial but quieter developments. The first was the emergence of the modern corporate form, with its key characteristics of limited liability, shared ownership, transferability of possession, and permanent existence. This new form of investment, which first manifested itself as the joint-stock company, had enormous flexibility, durability, and risk limitation that proved to be essential for financing and operating large and complex enterprises.

The second development was the Industrial Revolution. While it was a slow and painful transformation, often accompanied by urban squalor, wretched working conditions, and social strife, it forever altered the trajectory of the economic fate of nonelites. In particular, those beyond the landed gentry (notably, practitioners of commerce, manufacturing, and invention) at last began to share meaningfully in economic surplus. Gradually, there was an emerging trend toward meaningful savings that could be deployed for investment projects. In effect, it was the other side of the coin: the first development of the modern corporate form generated the seeds of demand for capital, and the long-term effects of the Industrial Revolution produced the means of satisfying these capital demands.

The third development was the construction of a means to connect empowered savers with these investment projects, which was accomplished through the emergence of public markets. The public market was, in the long term, the mechanism to join the two sides of the coin. Public markets offered liquidity, publicized value, broadcast availability, lowered transaction costs, and permitted investors to gain wide diversification with relative ease. Public markets, furthermore, aided in initiating the opportunity and need for regulation.

The democratization of investment is not a finished project. Just as the political democratization of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is still playing out (it left key demographics still disenfranchised and has not yet spread to all corners of the world), the project of democratization of investment is incomplete. A large swath of the population remains deprived of meaningful savings and thus is excluded from participation. Rules and regulations can still be enhanced to further level the playing field, and many international jurisdictions have yet to take up the banner of broadening investment opportunity. Nevertheless, the beginning of democratization itself has been a dominant force in the history of investment, and we can trace its lineage to these developments.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN CORPORATE FORM

The advent of the corporate form, as embodied in joint-stock companies, was a vital precursor to developing capitalism, greater economic progress, and widespread financing and ownership of commercial and industrial enterprises. While the focus of this chapter will be on the first Dutch and English joint-stock companies founded in the early seventeenth century, recall that the original precursor to the joint-stock company appeared more than a millennium before—the Roman societas publicanorum. As mentioned in chapter 1, these entities were created to bid on and service the construction of public works, engage in tax farming (the government’s sale of the right to collect particular taxes to a private enterprise), and provide goods and services to the Roman government. The societas publicanorum declined in popularity during the Roman Empire, as the government gradually inserted itself as the predominant player in these activities rather than outsourcing them to private concerns. After all, the Empire was not as interested in facilitating the decentralization of the activities of the state as the Roman Republic had been. And so this powerful form went dormant, and the elite maintained their exclusive right to the activity of investment.

It was not until medieval times that progress toward the modern corporate form began again. For instance, medieval commenda and compagnia were partnership forms that allowed the financing of commercial ventures—especially sea voyages for trade purposes—to be structured in ways that accounted for the economic differences between being an active participant in these ventures and merely providing financial support in the form of risk capital. This represented an important departure from a classical partnership in which all other partners had to agree to the sale of interests—and with good reason, as partners tend to be involved in the management of an operation and thus must ensure that the person to whom the interest is sold is actually effective and productive. In this new hybrid form, however, the use of shares opened new possibilities. With shares, consent is not needed, since the management of a shipping operation is not necessarily affected when one passive investor sells shares to another passive investor.

It was in the shipping industry that these arrangements were most common, and in twelfth-century Genoa, a major hub of shipping activity, it became more and more common to supply capital to shipping operations with loca (shares). Typically, the ship would be divided into somewhere between 16 and 70 shares, with the investment structure lasting just one voyage, rather than the life of the vessel. However, by the thirteenth century the use of loca began to decline as maritime insurance rose to prominence and it was no longer as necessary to spread risk and raise capital to undertake these voyages. For a brief time, though, loca were intensely popular in Genoa, and even investors who were not wealthy participated in the market.1

Finally, in the early 1550s the first joint-stock company, the Muscovy Company, appeared in England. It was started by English merchants and traders hoping to access wood, hemp, and construction materials in northern Europe. The earliest groups of traders were known as the Easterlings, and some etymologists believe that the term sterling comes from the name of these traders.2

The Muscovy Company came into being after a voyage to the White Sea. Although the first captain was lost, another sailor managed to navigate the vessel to Archangel (or Arkhangelsk) in order to parlay with Russia’s Czar Ivan the Terrible. These sailors sought permission to engage in trade, and Ivan acquiesced, giving the sailors a missive to the English king as his official acceptance. Because King Edward VI died during the initial expedition, it was ultimately Mary I, Queen of England and Ireland, who issued a charter to the company in 1555.3

There are other early examples of joint-stock companies—for instance, one of the first investments by the European public in the natural bounty of the so-called New World was, in fact, a joint-stock company. On April 10, 1606, King James I granted a charter for the London Company. It was inspired by English envy of the Spanish, who found massive quantities of precious metals in the New World. As a condition of the charter, King James I sought to cash in on what he hoped would be abundant profits and stated that one-fifth of the metal discoveries be ceded to the throne.4

The company was composed of 145 men who sailed from England to the New World between December 1606 and May 1607, making port in Virginia (hence the company’s later name, the Virginia Company). Investors who purchased shares in the enterprise capitalized the firm. The investor base was a motley lot: the upper echelons of civil society bought in alongside those with a thirst for adventure and speculation. Remarkably, these shareholders were fairly well organized. They created a “court” to manage operations, a body likely bearing some resemblance to what today would be seen as a participatory board of directors. This group proved to be reasonably effective when the venture failed to find the precious metals it had sought. It ordered a shift in operations away from locating metallic resources toward sustaining the colonizing population by selling rations, goods, and “patents” or “Plantations” (land deeds) to augment profits. It formed a subsidiary known as the Magazine to sell necessities, vestments, and rations to the colonists. This resourcefulness, while impressive, was not entirely popular with the colonists, who often found the prices to be outrageously high—an issue that was ultimately mitigated, to some extent, when the king placed a cap on net income from sales of provisions at one-fourth of sales. There are other examples of the shareholders’ aptitude. For instance, when the shareholding body determined that the Magazine was not distributing profits fairly to the Virginia Company, it swiftly removed the manager involved. Despite the shareholders’ relative success in exercising some control over operations, the company survived for only some eighteen years. The initial investors wanted to exploit gold and silver deposits, and without such a lucrative opportunity, the days of selling mostly to colonists were inevitably numbered.5

The Muscovy Company and the London Company had many of the characteristics that define the modern corporate form, but it was not until the seventeenth century that joint-stock companies started to exhibit the full range of modern corporate characteristics. Such companies included the prominent Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company, both founded in the seventeenth century. These two enterprises, both of which had relatively large market capitalizations, featured many shareholders who were not engaged in running the business and were created with limited liability in the modern corporate sense. Their mission was to finance long-distance and long-duration trade by committing capital for extended periods of time. The most striking corporate characteristics of these companies were their shareholder financing and their eventual permanent existence. In due course, the provision and withdrawal of capital to activities of the East India Companies became entirely separate from the acts of investment and disinvestment undertaken by their shareholders. These later acts were accomplished by the purchase and sale of the company’s stock in the open market and originally, therefore, by transactions undertaken between existing shareholders (the sellers) and other existing or new shareholders (the buyers).

The South Sea Bubble

No sooner had the modern corporate form emerged than the need for its regulation did as well. The South Sea Bubble, economically ruinous to a host of early investors, highlighted the dangers of a lack of adherence to fiduciary duty and revealed some of the weaknesses of this new form.

The South Sea Bubble began with the South Sea Company, founded by Robert Harley and John Blunt in 1711. The company was given unrestricted and monopolized access to trade in South America in return for agreeing to purchase the public debt that resulted from the War of Spanish Succession. At the time of formation, it was not known how the War of Spanish Succession would end, and because Spain had control over South America, there was an embedded gamble on the outcome of the war. After all, the company would do well if Spanish control over South America waned because of defeat but would have limited access if Spain held control. The South Sea Company was to receive the interest from the government, and the company performed even more debt assumption from the government in 1719. Initially, all parties seemed content. The government was able to pay a reduced interest rate, and the funds directed toward the interest payments were to be raised from tariffs levied on imported goods from South America. The debt holders generally embraced the idea, as they had an opportunity to benefit from potentially very lucrative trade while continuing to indirectly benefit from their former interest payments as the entity in which they held equity now received them.6

There was one problem: the company actually did very little trade in South America, in large part because Spain had maintained control of its colonies after the war and was not keen on other empires gaining footholds in its lands. Indeed, the bet on significant British involvement in South America did not pay off for the South Sea Company. In fact, most of the South Sea Company’s earnings were derived from the returns on public debt. The management wanted to push up the stock price, but clearly it could not do so by passing on the sad truth about its measly returns in South America. Instead, management decided to concoct a tale that it had made substantial sums from the South American trade. Investors believed the fabrication hook, line, and sinker, and the deception (along with a broader bubble in those trade enterprises that followed the lead of the South Sea Company in making extravagant claims of success) caused the share price to swell from £128 in January 1720 to £550 in May. The stock eventually collapsed from a height of £1,050 per share, and soon, after the ensuing investigations, it became clear to the shareholders that they had been swindled.7

The news, as can be imagined, did not go over well. One shareholder who lost a sizable sum was so incensed over the entire affair that he shot founder John Blunt for his complicity. The public rhetoric was equally charged. While a more unruffled member of Parliament called the event “a notorious breach of trust,” another proclaimed that the fraudsters should be placed in sacks with snakes and loose change and thrust into the river to drown.8

The South Sea Bubble brought serious harm not only to much of the investing public but also to the broader English economy. One of the foremost ironies of the episode was the passage of the Bubble Act of 1720, which required all joint-stock companies to possess royal charters. Contrary to common conception, this was not passed out of a desire for reform; rather, it was passed prior to the collapse of the firm and was meant to aid and insulate the South Sea Company from competition for investors’ funds by preventing other smaller entities from marketing shares, as they did not possess the required charter.9 Nonetheless, the Bubble Act came to be used to regulate these early companies and made them less likely to do widespread harm. Ultimately, the South Sea Bubble reminded investors of exploitable information asymmetries between the body of shareholders and management, and it drove many to approach the task of allocating money with greater scrutiny and diligence. In the end, of course, the fraudulent activities of Enron and Bernie Madoff are echoes of this forerunner some three centuries earlier.

Adam Smith, the oft-cited “father of modern economics,” took an entirely adversarial view of the structure of the joint-stock companies and the notion of investment management more broadly. Of course, Smith was highly influenced by the South Sea Bubble collapse, and in The Wealth of Nations he wrote, “Negligence and profusion, must always prevail, more or less, in the management of the affairs of such a [joint-stock] company.” He claimed that the fiduciaries could not possibly be fully dutiful and completely concerned about the welfare of shareholders because the money is not their own: “The directors of such companies, however, being the managers rather of other people’s money than of their own, it cannot well be expected that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in private copartner[ship] frequently watch over their own.”10 Adam Smith seemed to apply the famous principle of self-interest to the management of investment funds and, in so doing, deemed it a poor idea. His view of potential misalignment between owner and manager was not entirely misguided, but he did not appreciate that investors could develop more sophisticated governance and incentive structures to enhance alignment.

Naturally, a wide array of ownership structures developed throughout history, and the joint-stock company was the seed that would eventually blossom into the modern corporate form. These joint-stock companies first tended to involve trading firms: the Muscovy Company with English merchants trading in northern Europe and the London Company (later the Virginia Company) that aspired to enjoy the wealth of the New World and ended up transforming into an organization to profit from settlers. Over time, the sophistication of these trading companies grew with the East India Companies that were even more evolved, involving a clearer separation of ownership and management and an eased transferability of possession. The structure was, of course, far from perfect and had to experience an abundance of growing pains, of which the South Sea Bubble was perhaps the most obvious early manifestation. Adam Smith aptly pointed out the problem of agency—namely, how can the incentives of those who own the firm be well aligned with those who manage it? Of course, Smith believed this was a fundamental flaw, but as time would prove, it was an issue that could be addressed through more proper regulation, enhanced governance rights of shareholders, and castigation of managers who ignored their obligations to their stakeholders.

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Although Smith’s protestations regarding joint-stock companies did not force them out of existence, in general his writings were quite influential. Indeed, his new economic theories, emphasizing strong market competition and laissez-faire economics as the means by which to innovate and prosper on a societal level, were particularly relevant as Britain and other European nations were increasingly turning away from mercantilism and embracing free trade. Starting with the First Industrial Revolution, from about 1760 to 1840, radical changes in iron production, the utilization of steam power, and the mass manufacture of textiles began to reshape the global economy and labor force. The Second Industrial Revolution, also called the Technical Revolution, involved the incorporation of new materials (most notably steel) on a massive scale, technologies (like the internal combustion engine and the radio), and electric power. Beginning in the middle of the 1860s, this second stage of the Industrial Revolution extended until World War I. This process of industrialization, one of the few times in history that humanity altered the very structure of existence under which it had lived for centuries, was a major accelerator of the democratization of investment. In fact, the Industrial Revolution would have been impossible without the evolution of the investment and banking systems. It also marked the historically critical inflection point in the trend of wealth generation and democratization. That is, it facilitated a slow retreat of nearly exclusive control of surplus resources by the elite to a slowly growing possession of surplus by broader swaths of the population.11

Of course, the Industrial Revolution was also enabled by earlier economic shifts, manifested at both a macro and micro scale. On the macro level, the commercialization of Europe in large part served as a contextual precursor for the Industrial Revolution. Many Europeans were already familiar with market production and were not manufacturing all of the goods they used individually but rather were obtaining them through means of trade and exchange. The role of the national banking system in England as a facilitator of sales and catalyst for the velocity of goods exchange was instrumental as well. And on a more micro level was the economic dynamism of individuals and their family units; much as in earlier European eras, prosperous merchant families and families of industrialists began driving their own economic success.12

The eighteenth century’s demographic factors went a long way to catalyze the Industrial Revolution, and in Great Britain in particular. For one, there was a great deal of population growth, partly due to a break in the stream of plagues and disease outbreaks that had afflicted Europe for centuries. Coupled with this was the availability of resources, a willingness to innovate, and technological advances that together helped enable this transformation in industry. For instance, Johannes Gutenberg’s revolutionary printing press of the fifteenth century clearly facilitated the diffusion of knowledge that made the Industrial Revolution—and its necessary technological innovations and inventions—possible in the first place.

Among the other facilitating technologies of the Industrial Revolution was James Hargreaves’s spinning jenny, a spinning frame with multiple spindles that vastly increased production volume in the textile industry. Combined with the flying shuttle, the spinning jenny took the textile industry into the next competitive era. James Watt’s late eighteenth-century steam engine changed most industries using mechanical power, especially transportation and agriculture, quite significantly. The previous costs of producing this mechanical power, no matter the application, were generally higher than the costs of heating water to steam, and thus enormous cost savings were realized and industrial and transportation projects became more feasible. All of these technologies of the Industrial Revolution made life easier for their innumerable users and facilitated much of the economic growth and societal advancement of the Industrial Revolution era.13

The Nature of Capital Demands in the Industrial Revolution

Over the long term, the Industrial Revolution influenced investment by creating a surplus shared by many beyond those in the upper echelons of society. The relationship between industrialization and public market investment, however, does not hold in the reverse. In other words, while industrialization may have produced surplus that could be invested in the long term, financial institutions beyond the banking system at the time were not really as crucial to industrialization in the first place as one might be inclined to believe.

To understand this, it is possible to bifurcate the capital demands of the First Industrial Revolution into fixed capital and working capital. Fixed capital requirements were low and were mostly met by entrepreneurs and their families, not by formal banking institutions. In fact, if one analyzed the division of the aggregate level of capital during the First Industrial Revolution, the share that belongs to fixed capital would have been between 50 and 70 percent of the total capital. However, this overstates the role of fixed capital in the actual industrialization process because the industries where industrialization began, such as textiles, did not require significant fixed capital.14 For instance, perhaps the most significant fixed capital expense in an industry like textiles is the space where production occurs—a converted warehouse, most likely.15 This would change by the time of the Second Industrial Revolution, which, by virtue of the specialized heavy machinery involved, necessarily required large quantities of fixed capital, but this was not yet the case in the initially industrializing sectors.

For those entrepreneurs and families involved, funding of fixed capital in the early industrializing sectors typically entailed reallocating the wealth derived from agricultural activities, ownership of natural resources, and other businesses toward these industrial enterprises. This tendency toward the self-financing of fixed capital also drove businesses to reinvest earnings in lieu of distributing them when a strategy of growth was pursued. Self-financing was also attractive to entrepreneurs as a means of keeping the requisite sources of outside fixed capital under control. Many perceptive business owners made decisions to keep fixed capital requirements low by renting rather than owning physical space, for instance.16

It is also important to note that working capital demands—unlike their fixed capital counterparts—were high. Working capital (or circulating capital) demands refers to the liquidity needs of the business for inventory, debt service, payroll, and other short-term financing requirements. The relative magnitude of fixed and working capital needs is exemplified by the northern and midland textile sectors before 1815, where the working capital commitments were three times the fixed capital demands. Given the greater requirement for working capital, it is believed that these demands were frequently too large to be satisfied by the entrepreneurs themselves and were met instead by banks. As we will see, the decentralization of banks contributed significantly to meeting this demand for working capital.17

The Banking Institutions of the Industrial Revolution

The role of the banking institutions—a source of capital supply—is also very significant to the Industrial Revolution. The eighteenth-century English banking system was run by three categories of players: the Bank of England, the private banks of London, and the country banks. The Bank of England was chartered in 1694, prompted in large part by the dismal state of affairs of the English navy, which had recently begun experiencing steep losses in battle. It was a wake-up call for Britain, and the English realized how sorely they required a revitalization of their maritime forces. This, however, proved to be a formidable challenge because King William III’s ability to access credit (certainly not improved in the wake of such defeats) was limited, severely limiting how extensive this nautical overhaul could be. And so the Bank of England was born, with the goal of furnishing credit to William III. The Bank of England was not, at this time, a central bank wielding control over the supply of money, but it nonetheless became a national institution.18

The private banks of London grew throughout the eighteenth century, from a total of thirty in 1750 to fifty by 1770 and seventy by 1800. These private banks had two purposes. The first was to supply funds for short-term loans and to trade and help settle bills of exchange. The second, which became more important after 1770, was to serve as the intermediary between the Bank of England and the third type of banking entity, the country bank. These country banks, as the name would suggest, operated beyond urban London. The private banks helped move specie and banknotes back and forth between the country banks and the Bank of England to ensure the former were properly capitalized.19

While the growth of the private banks in London throughout this period may have been impressive, the number of country banks grew even faster. In 1750, they numbered just 12, but by 1784 they hit 120, by 1797 there were 290, and by 1800 there were 370 country banks. The number of country banks varied in proportion to the strength of the economy and the state of credit at the time. For instance, they tended to do well when the Bank of England suspended the ability of holders of banknotes to make conversions to gold during the wars with France in the late eighteenth century. Of course, the inverse held as well: when the economy was doing poorly, these country banks were quite vulnerable to bankruptcy. Of the 311 bankruptcies that occurred between 1809 and 1830, more than half of them happened in the crisis intervals from 1814 to 1816 and 1824 to 1826.20

Some of these country banks were created by families who accumulated fortunes in other trades and found themselves with adequate resources to capitalize a bank. Of course, these country banks accepted deposits as well, but the founding families’ wealth made it possible to open the doors of the country banks in the first place. For example, Gurney’s Bank (one of the banks that would merge into Barclay’s in 1896) was started by the descendants of John Gurney of Maldon, who aggregated a fortune in the wool trade. As Quakers themselves, they attracted many of their early depositors from the Society of Friends, and over time, their reputation spread as a trustworthy institution.21

In addition to driving a change in structure toward joint-stock banks, the Bank Act of 1826 strengthened the scope and operation of country banks by granting permission to rural banking institutions (those beyond about sixty-five miles of London) to issue banknotes. One cause of this decentralization of banking in early to mid-nineteenth-century England was the refashioning of the international political landscape. During the reign of Napoleon, the English government had been particularly keen on ensuring that financing the national debt was a foremost priority of English capital markets. It was only with the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815 that the English became less concerned with the prospect of a French-dominated Europe, and the government was able to relax its preoccupation with putting the national coffers among the first to receive service from banks and lenders.22 Therefore, there was a resulting liberating effect on capital markets toward private enterprise. Beyond decentralization, the country banks served a fundamentally different role than did other types of banking institutions at the time. In fact, some of these country banks looked more like modern venture capitalists than conventional banks because country banks provided financing to the riskier, more entrepreneurial projects that the larger, more traditional banks tended to avoid.

Much of the nineteenth-century banking experience thereafter was marked by powerful consolidation. In lieu of a multitude of independent country banks, these establishments began to merge with other firms, acquire smaller players, and outcompete their peers that were slower to adopt this trend toward greater scale. Of course, the banks that became larger by way of acquisition still needed an instrument to exert wide geographic influence, which manifested itself in the phenomenon of branching. Banks could still penetrate provincial markets, but they now operated under a banner of other banks, enjoying a broader capital base, a wider diversification of loans, and economies of scale. Between 1825 and 1913, there was a precipitous drop in the number of banks in Britain, from 715 to 88. However, at the same time, the rise in the number of branches more than compensated for this, rising from about 850 to over 8,000 during this same period, indicating an even more extensive dispersion of banks integrated into fewer and more powerful corporate outfits.23

Long-Run Improvements in Wealth Generation

It is difficult for a modern person to understand how radical a transformation it was to have the generation of savings begin to spread from the prominent and landed gentry, first to merchants and manufacturers and later to others. Before the Industrial Revolution, the savings of most economies were held almost exclusively by a small elite class. Consider, for instance, the conditions of the poorest classes during the bubonic plague of the 1600s. Most became so desperate for food and clothing that they stole from the bodies of the dead, thereby spreading the disease. The town councils of many areas in Europe had no choice but to take notice and begin restrictions and provide aid for the lower classes.24 The town councils were forced to provide assistance for the many who had no coinage to spare.

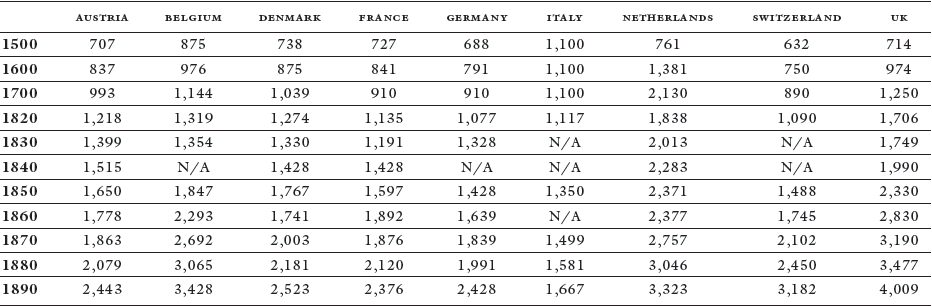

An analysis of GDP per capita leaves very little doubt that industrialization was transformative in bringing about sustained economy-wide growth in a manner that was essentially unprecedented in history (see table 2.1). The United Kingdom, for example, saw its GDP per capita approximately triple from 1700 to 1880. Considering the slow growth of the GDP in the years leading up to the Industrial Revolution, the new growth was indeed miraculous.

TABLE 2.1

GDP per Capita from A.D. 1500 to A.D. 1890 in Selected European Countries (1990 International Dollars)

Source: Angus Maddison, Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 A.D.: Essays in Macro-Economic History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), Table A.8; Angus Maddison, The World Economy: Historical Statistics (Paris: Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2003), 58–61.

There are other metrics suggesting that the standard of living of the British was also slowly becoming better over this interval, consistent with the economic data. While perhaps today it would not be regarded as the optimal proxy for quality of life, rising sugar consumption typically implied a shift beyond sustenance and toward richer food. Between 1815 and 1844, the average person in England consumed less than twenty pounds of sugar per year, but from 1844 to 1854, average annual sugar consumption grew to about thirty-four pounds per year, and by the 1890s, was around eighty to ninety pounds.25

Difficult Conditions for Laborers

The precise effect of the Industrial Revolution on labor and wages remains a contentious issue among economic historians, and clearly not all the nuances of the various arguments can be captured here. The view proposed here is that the Industrial Revolution was a process that induced substantial growth in the long run, though in the short run it produced very difficult living conditions for many urban laborers.

One debate among historians concerns the precise moment when wages for laborers themselves actually improved. A fair amount of compelling scholarship suggests that the period around 1820 represented an inflection point for labor, before which wages tended to stagnate and after which wages tended to march upward.26 While wages for laborers did tend to rise after 1820, many laborers were far from being well off. Industrialization produced a larger concentration of the population in urban centers. Many who had worked comfortably in cottage industry and operated out of their bucolic homesteads found themselves plunged into urban squalor when they relocated to find work in the cities.27 The influx into some cities was so great that the development of infrastructure (such as sanitation) and strong institutions (including law enforcement) seriously lagged behind what was necessary to keep a well-ordered metropolis.

Of course, efforts to remediate these hapless urban environments were not helped by the political climate at the time. Class conflict boiled over as laborers found themselves not sharing proportionately in the prosperity of the age, and the affluent often staked out an entrenched position to oppose meaningful political reorganization to that end. There was little interest by the latter in ameliorating the conditions the former were enduring. Indeed, one historian has gone so far as to assert, “No period of British history has been as tense, as politically and socially disturbed, as the 1830s and early 1840s.”28 The political movements collectively known as Chartism emerged beginning in 1838. These movements converged ideologically on a document known as The People’s Charter that outlined a set of six proposals for reform to the political system to render it more accessible to the general population, such as extending the vote to all men and removing any requirements for the ownership of property for candidates running in parliamentary elections. Though Chartism began to fade by 1848, the class conflict prompted by the disproportionate effect of the Industrial Revolution in improving the lots of various income groups was far from over.29

One of the fascinating aspects of early English industrialization in retrospect was its highly controversial nature socially and abroad. The Germans reviled what they had seen in England during English industrialization. Many Germans cited the horrid urban filth, the rampant poverty, and the repugnant working conditions as the basis for detesting industrialization.30 Indeed, many of the works of Charles Dickens, like Hard Times and Oliver Twist, dealt intimately with the subject and shared the wretched early consequences of British industrialization with the world.

There was also a significant contingent of the laboring class that certainly did not share at all in the growth—namely, those who remained on farms. Industrialization was a much more potent force in the city than it was in the agrarian setting. While nonfarm labor wages increased by some 80 percent from 1797 to 1851, farm labor wages actually dropped slightly over this period.31

White-collar workers did tend to outperform blue-collar workers in terms of income growth: blue-collar workers tended to see a doubling of wages from 1781 to 1851, whereas white-collar workers saw wages quadruple.32 Indeed, the process of industrialization is linked inextricably to the phenomenon of increased urbanization from which a wide variety of occupations (and particularly white-collar workers, whose work is often tied to or done more fully in cities) benefited.

Ultimately, it is clear that wages did rise for many groups in the Industrial Revolution, but what was the effect on savings? Having an understanding of the changes in total savings is critical in thinking about capital formation, since the amount of savings determines the quantity of liquid resources available for investment. The methodologies employed to answer this question are far from perfect because they often involve making an assumption of an aggregate savings function that is not easily validated by the historical record. Nevertheless, there is reason to believe that much of the net growth in savings was due more to rising incomes than to a large increase in savings rates.

The observed savings rate increased from about 8.5 to 12.5 percent during the Second Industrial Revolution, while gross national income grew by over threefold in this same time period.33 The previously lower wages left little surplus for discretionary activity at all, as little was left once housing, food, and other necessities were satisfied. The Industrial Revolution profoundly altered the landscape of investment because savings—the basis of all investment—increased as wages grew. Although not immediately, this put the economy on a trajectory toward a democratization of mass saving and investment by way of these higher incomes that would have otherwise been impossible for such a large swath of the population in the subsequent twentieth century.

Breadth of the Industrial Revolution

Although the Industrial Revolution did begin in just a few select sectors, it did translate into growth across a much broader portion of the British economy. Indeed, Britain saw strong increases in exports in a wide variety of industries beyond those touched directly by the radical innovations that brought on the entire industrialization process.34

However, while England is perhaps the most discussed and most studied nation when it comes to analyzing the transformative effects of the Industrial Revolution, the history of the experience of its northern neighbor, Scotland, is also quite rich. The experience of the Scottish during industrialization was inextricably linked to the Scottish Enlightenment, the period of intense intellectual and scientific achievement in the eighteenth century. The Scottish Enlightenment involved revolutionary thinkers like Adam Smith, David Hume, and John Millar, intellectuals who transformed economics, philosophy, physics, and chemistry. Though it is easy to identify a few key thinkers and their corresponding achievements, the Scottish Enlightenment had a more crucial and wider-ranging effect: a dedication to the improvement and reworking of society. Scottish intellectuals had a strong sense of the importance of infrastructure in greasing the wheels of the economy. An economy can thrive when infrastructure, like canals and roads, is constructed to facilitate the movement of products and labor. Many Scottish landowners were quick to utilize new agricultural techniques as well, which allowed Scotland to achieve self-sufficiency and reduced the transfer of capital abroad, leaving more for domestic investment. There was also awareness that the institutional environment exerted a very tangible influence on the operation of the economy, and as such, many Scottish intellectuals began to advocate for the revamping of outmoded legal arrangements.35 The legal framework in which this new commercial activity occurred needed to adapt to a changing world.

In terms of the mechanics of investment, Scotland also employed a rather different partnership structure than did England when it came to organizing an enterprise. Unlike the English common-law variety, the Scottish partnership was quite similar to the French civil law structure that emphasized the dissociation of ownership and management. In the Scottish arrangement, only the inside partners could make decisions on debt, contracts, or other major financing and operational decisions, while the outside partners were far more passive. On the one hand, the Scottish partnership still had the shortcoming of unlimited liability for all partners, including the passive outside partners, and thus created a strong incentive to ensure that partners with limited means were excluded from the acquisition of interests. This incentive arose because in the case of catastrophe where liabilities exceeded assets, partners would need to surrender their own outside resources, and if one partner was unable to do so, his share was borne by all the other partners. On the other hand, it does appear that the Scottish banks were, in fact, more stable than their English counterparts, as evidenced by the lower failure rates of banking institutions during periods of fiscal crisis in the early nineteenth century.36

Changing Modes of Capital Formation in the United States and France in the Second Industrial Revolution

Modes of financing changed over time in other nations as well. Many of these changes can be seen, for instance, in the markets of Cleveland, Ohio, which was a hub of innovation during the Second Industrial Revolution in the United States. However, these innovations during the Second Industrial Revolution were of a different flavor in that they tended to be much more capital intensive than their predecessors in the First Industrial Revolution. Many of the most transformative inventions could not be brought to market without substantial access to capital, and many entrepreneurs simply lacked the means to self-finance their new technologies. As a result of the greater capital demands, more innovation was localized within existing companies. That is, instead of entrepreneurs or inventors conceiving of an idea and starting a firm to promote the commercialization of the technology, many of the larger existing firms spent handsomely on research and development, and more products came out of these efforts than before.37

To be clear, the days of the entrepreneur-led company were far from over; such entrepreneurship was just slightly harder to accomplish with the greater capital demands. Inventors were still most likely to grant their patent rights to a firm in which they possessed equity, rather than selling those rights to another firm. Entrepreneurs were still interested in preserving autonomy and control, and some still managed to do so despite the increased difficulties. As one can imagine, it was easier to attract capital if one had a history of successful inventions. This is evidenced in a variety of historical examples, including the story of Charles Brush, who invented arc lighting and founded Brush Electric. Even after he left that line of business and tried to pursue enterprises in other industries, his past success seems to have made it far easier for him to attract capital. Past successes gave firms a second immense advantage: the ability to attract talent. Many bright young scientists and inventors wanted to join Brush Electric ranks, well aware that they would be on the cutting edge and that they would work alongside brilliant colleagues.38

During this time, the operation of banking institutions also changed. Whereas during the First Industrial Revolution many families with wealth from preindustrial activities were founding and operating small banks, in the Second Industrial Revolution it was industrial magnates who were now operating many banks. For instance, Robert Hanna, who made a fortune in the Cleveland Malleable Iron Company, founded the Ohio National Bank.39 It is very likely that these industrialists were more able administrators, for they were the products of the very industrial success in which they were intending to invest.

In France, though, many small banks continued to be run by older families with preindustrial wealth, even during the Second Industrial Revolution. In fact, many small banks were funded by these families and would deploy capital locally, much like the country banks of England. That said, these small banks funded by families had to share the market with a very adept financing institution: the merchant bank. Large merchant banks did quite well in capturing firms with international operations, as they were able to handle the settlements of funds across borders with ease. The small merchant banks, though, likely realizing they could not compete well in capturing large companies that traded internationally, tended to take more risk and invest in industries that were novel and growing, looking like modern venture capital firms.40

Thus, to summarize, the influence of industrialization on the character and practice of investment can be broken down into several lessons. The First Industrial Revolution was largely self-financed because there were low fixed capital demands. There was also a sophisticated network of banks emanating from London to the private banking intermediaries and ultimately to the country banks that financed higher-risk investment projects. The character of financing changed during the Second Industrial Revolution when high capital costs demanded external financing solutions that could no longer be accomplished through self-financing channels. Most of all, there are crucial lessons with respect to growth and wage improvements. The effect of the Industrial Revolution on wages was not immediate, and many people suffered from terrible working and living conditions. In addition, the effect of the Industrial Revolution on wages was not uniform across all types of labor, disproportionately affecting urban workers over farmers. The third lesson is that although not all workers benefited equally, the Industrial Revolution was also not just a phenomenon limited to a small portion of the economy. Finally, and perhaps most important of all, the Industrial Revolution did, in the long term, prompt the beginning of an unprecedented growth in wages for the average worker.

THE ADVENT OF PUBLIC MARKETS

To genuinely appreciate the emergence of the public market, it is necessary to look farther into history to examine how government lending and asset transfers occurred before this crucial development.

Before the Public Market

The earliest markets for securities resembling our modern system arose in twelfth-century Italy. While central governments and large corporations rule today’s bond market, at that time most debt instruments were actually issued from local governments and landowners. The most notable innovations in debt issuance were in the city-states of early Renaissance Italy. Genoa in particular was a pioneer in securitizing public debt. As early as 1164, the city created a form of public debt in which members of an association, known as the compera, paid to receive a share, called a luoghe, or claim, on the debt. Venice, by contrast, tried to satisfy its debt requirements by asking wealthy citizens for voluntary loans. But eventually these loans proved insufficient, and the city turned to forced loans. In turn, as government spending grew larger and larger, forced loans failed to satisfy the city-state’s credit requirements. Consequently, Venice consolidated all of its outstanding debts in one fund, the Monte, in 1262; all claims to debt were exchanged for shares in the Monte, which earned 5 percent interest. Florence and Genoa created similar mechanisms in 1343 and 1407, respectively. Most investors were wealthy citizens, though some middle-class citizens and some foreigners did buy the funds. Because shares of the Monte were easily transferable, a secondary market developed. Shares traded at market price, which depended on expectation of the government’s ability to pay interest and the availability or reliability of other investments, demonstrating the influence of this secondary market on the exchange of securities.41

In addition to this trade in public debt was a growing use of private debt. This network of credits and debits was increasingly based on nonnegotiable bills of exchange. A bill of exchange is a promise by the signer to pay a certain amount of money on a certain date. A nonnegotiable, or nontransferable, bill of exchange is written to a specific person, and only that person can receive the money. A negotiable bill of exchange, however, is payable to the bearer, who is not necessarily the original owner of the instrument. This was a major improvement over shipping currency from place to place, a dangerous and unreliable practice. It was also an improvement over the system at the periodic fairs in Champagne, France, during the twelfth century, in which fair authorities and merchants simply recorded credits and debits accrued by the end of one trading period and carried them over until the next fair took place. The relatively widespread use of nonnegotiable bills of exchange in Renaissance Italy was also convenient because bills of exchange payable in a foreign currency presented a true risk, related to the rate of foreign exchange, thereby skirting the usury prohibitions of the period.42 At the time, there was no secondary market in these financial instruments because they were nonnegotiable, but this period set the stage for the later securitization of debt in negotiable, or transferable, bills of exchange.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the center of financial activity and power shifted from Italy to northern Europe, where various exchanges, known as bourses, developed. The most important of these exchanges in the late 1400s was Bruges, though dominance shifted to Antwerp in the 1500s and this city became very powerful by the latter part of the century. Other, less important bourses emerged in Paris in 1563, London in 1571, and Frankfurt in 1585. At first in these markets, commodities, crafts, and financial products were exchanged side by side, much as they were in the fairs of late medieval France. Increasingly, though, trade in goods and trade in securities became separated. In large part, the financial products exchanged at these fairs were currencies and bills of exchange, introducing new risks—exchange rate fluctuation and default, respectively—and increased liquidity to the market. To a smaller but still notable extent, debt was often exchanged at the bourses. Antwerp even had a notable market for municipal annuities. While most participants in the market were quite wealthy, likely nobility and landowners, some participants belonged to the “middle class.” In 1545, an estimated 25 percent of purchasers were craftsmen, 21 percent were administrative officials, 17 percent were widows, and 16 percent were merchants.43

Despite all of the rather advanced features of debt in Italy and bourses in Antwerp and northern Europe, it is important to note that there was still no truly public market or stock exchange. At this time, there were few tradable financial assets, few people holding such securities at any given time, and few exchanges of those securities. As a consequence, no formal organization for trade in financial instruments existed, and there were no specialized intermediaries who facilitated such transactions. Instead, transactions were personally negotiated and executed at general mercantile exchanges. The supply of and demand for securities and the volume of trades simply did not yet support the creation of a public market.44

The Beginnings of the Public Market: Amsterdam

By the dawn of the seventeenth century, negotiable securities representing shares of a business or of government debt were gaining in popularity across Europe. As ownership of and interest in these securities became more widespread, formal markets were organized for their purchase and sale. As volume grew, those who facilitated these exchanges became full-time professionals who developed specialized techniques for the execution of transactions.45 Thus began in earnest the stock exchange in its modern form.46 As it did so, Amsterdam was established as the center of the European financial world in the first years of the 1600s.47 The old center of Antwerp, now tarnished by sovereign debt default and beset by Spanish attack in the Eighty Years’ War, was no match for the newly ascendant city.48

One major development cementing Amsterdam’s important new role was the creation of the Amsterdam Wisselbank clearinghouse in 1609. While merchant banks in Antwerp, London, and Amsterdam had previously coordinated the flow of credit and debt in the European economy, the creation of a centralized location for account settlement represented significant progress over what had been a less efficient and less coordinated process.49

The next important step toward the development of the modern financial system was the creation of a joint-stock company whose shares were bought and sold on a public market.50 Given that Amsterdam was the financial center of the Western world at this time, it is no surprise that this innovation took place there. The Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) was chartered in the early 1600s,51 and by 1609 its shares were widely traded in a secondary market on the nascent stock exchange in Amsterdam.52 Shareholder rights differed somewhat from today’s expectations in that stockholders were not allowed to vote on the company’s decisions, though they were paid a dividend. The dividend was often quite high, averaging 18 percent per year.53

Although Amsterdam was the first city to develop specialized intermediaries and many techniques that are hallmarks of the modern stock market, the city’s stock exchange was not made a formal institution until 1787. As such, the first organized stock market was created in Paris in 1724, limited to sixty specialized intermediaries (agents de change) and self-governed with a written code of conduct.54 Furthermore, Amsterdam lagged behind other cities in the development of a price list for securities. While a price list existed in London as early as 1697, such a list was not available in Amsterdam until 1795.55

Joint-stock companies had existed in England since well before the Dutch East India Company. However, the securities for these joint-stock companies, which were focused primarily on trading ventures, were not conducive to actual trading. Shareholders were subject to unlimited liability, and their numbers were few. Furthermore, though shares were negotiable, it was difficult to transfer them, so transactions happened almost exclusively among friends and family and no true public market developed.56

While the Dutch-English link was already strong in the mid-1600s, with connections through the trade of bills of exchange, it was the Glorious Revolution of 1688 that hastened the development of an English financial system resembling that of Amsterdam. In that year, James II was exiled from England and William of Orange, stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, became king, bringing his Dutch advisers with him.57

The first joint-stock company chartered after the Glorious Revolution was the Bank of England. Created in 1694, it was created largely to provide much-needed credit to King William III’s government, as described earlier in this chapter. It was analogous in many ways to the Amsterdam Wisselbank, though it was also more efficient in some ways. One significant divergence from the most famous Dutch joint-stock company, the VOC, was that stockholders in the Bank of England were given voting privileges. However, this had no real meaningful impact because great wealth was required for effective voting.58

The English stock market began at the turn of the eighteenth century in the coffeehouses on Exchange Alley, a street near the Royal Exchange marketplace in London.59 At Jonathan’s Coffeehouse, John Castaing began offering a price list for securities that were being bought and sold privately in the city as early as 1698, bringing some order to the prevailing chaos and marking an important step toward the organization of trading in London.60 Traders at the time were even licensed by the City of London.61 Though several coffeehouses served as centers for information and financial transactions, Jonathan’s became the most important and dominated the market for exchange.62

The stock exchange in many ways represented a social benefit. While the Bank of England was the original organ designed to help issue government debt, the stock exchange also helped England to borrow money at historically low interest rates and to raise substantial war money in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.63 In turn, the need to raise these funds helped the stock market to develop. However, these new opportunities also came with challenges. The South Sea Bubble of 1720, as described earlier, rocked the English financial markets. As a result, the system, which was already under some measure of government control, became more strictly limited through the Bubble Act of 1720. Much government regulation at the time was fueled by anxiety rather than logic, and most regulations were weak. However, the Bubble Act was an exception to this rule. It significantly regulated the formation of joint-stock companies and curtailed issuance of equity, limiting market growth for over a century.64

In 1760 there were 60,000 holders of British government debt, indicating the level of public participation in the financial markets. There were even fewer joint-stock company shareholders, though trading in equity was more common than in government debt because joint-stock dividends were uncertain and subject to much speculation.65 This figure represents just over 1 percent of the population of England, estimated to be approximately 5.75 million people at the time.66

Around the turn of the nineteenth century, the stock exchange underwent significant evolution. In 1773, the exchange moved to a new building and was reorganized as a joint partnership, briefly named The New Jonathan’s and then soon renamed again as The Stock Exchange. Multiple price lists were consolidated into a new publication, the “Course of the Exchange,” evidence of greater coordination and organization. In 1801, the group was reorganized again, this time as a joint-stock corporation. The new regulations and formalization associated with this transformation established the exchange in its modern form. The next year, the exchange moved to a new building. Finally, the Bubble Act of 1720 was abolished in 1825, accelerating the creation of new companies and fueling growth in the financial system. Apart from innovations within the financial system, the emergence of London as the new world financial center was fueled by the European political context. With the French Revolution beginning in 1789 and the Napoleonic Wars lasting until 1815, disruption and destruction in France and the Low Countries cleared the way for a rising England.67

In the United States, the federal government floated $77.1 million in debt in 1790 to pay back costs incurred by the American Revolution, giving birth to the first US public debt markets.68 On May 17, 1792, the Buttonwood Agreement (so named because it was signed under a buttonwood tree by twenty-four stockbrokers) was executed. Soon, in 1793, the Tontine Coffee House in New York City became a forum for trading government debt and equities, while many of the stockbrokers’ colleagues traded securities in the street nearby.69

The Buttonwood Agreement created what is today the New York Stock Exchange. It is of interest that the agreement specified that the brokers were to deal directly with one another and that commissions for trades would be twenty-five basis points (or one-fourth of 1 percent). The influence of auctioneers, who often charged very high fees and failed to create order in the transaction process, was curtailed within the exchange for the first time. The new organization was called the “New York Stock & Exchange Board.”70

Three decades later, the traders who continued to trade in the streets of New York outside Water Street and Wall Street came to be called curbstone brokers. Typically, the curbstone brokers would be heavily involved in making markets in higher-risk firms, like turnpike or railroad companies. The California Gold Rush of the 1840s only drove business further for these curbstone brokers, with mining companies being added to the mix. By 1859, oil was discovered in western Pennsylvania and oil stocks began trading among the brokers as well.71

In 1863, the New York Stock & Exchange Board’s name was shortened to the New York Stock Exchange, or NYSE. In 1868, membership became a valuable commodity—one could join the NYSE only by purchasing 1 of 1,366 existing seats on the exchange.72 Meanwhile, the curbstone brokers needed better infrastructure. They formed the Open Board of Stock Brokers in 1864, merging with the NYSE five years later. However, the curbstone market continued to exist. In 1865, after the Civil War ended, these brokers began to trade stocks in small industrial companies such as those dealing in iron, steel, chemicals, and textiles.73

The turn of the twentieth century brought immense institutional change in the history of public stock exchanges in the United States. By this time, the NYSE had been recognized as a leading American financial establishment. Trading volumes skyrocketed in the second half of the nineteenth century, and the exchange saw average daily trading volume reach 500,000 in 1900 from 1,500 in 1861.74

At the same time, the curbstone brokers were moving quickly to institutionalize their own trading framework. Emanuel S. Mendels, a prominent curbstone broker of the time, began to organize the market and tried to strive for ethical dealings in trading shares of these companies. In 1908, he established the New York Curb Market Agency, which attempted to codify trading practices further and set rules by which brokers should operate. Seven years later, this agency created the constitution and framework for the New York Curb Market, which moved to a real building on Greenwich Street in lower Manhattan in 1921. In 1953, the New York Curb Exchange would change its name to the American Stock Exchange.75

The Effects of Industrialization and Technology on Public Markets

The late 1800s and early 1900s saw the emergence of the first truly global market, largely fueled by historical context and technological innovation. To start with, the Second Industrial Revolution during this period fueled corporate demand for capital that could be used for expanded business operations, primarily for investment in fixed capital such as machines and factories. Furthermore, many governments loosened restrictions on corporate formation at this time, making it easier for entrepreneurs to start their own businesses; these new businesses, then, issued debt or equity for the first time, further fueling financial markets.76 As a result of these changes, the combined capitalization of these enterprises exceeded the gross debt of nations for the first time in the early twentieth century.77

Technology also played a vital role in the continued evolution of public capital markets. The most influential technologies were those that affected the spread of information, given the importance of accurate data in making financial decisions. The first in a series of such inventions came in 1844 with the invention of the telegraph, which allowed relatively convenient and immediate communication among markets and cities. In 1866, the first transatlantic cable was completed, allowing near-instantaneous communication between the key global financial centers of London and New York. The next year, the stock ticker was introduced. This specialized telegraph receiver, invented by Edward Calahan in 1863, printed stock symbols and prices on a paper tape, providing a mode of communicating financial data even more conveniently than the telegraph. Finally, the first telephone was installed on the floor of the NYSE in 1878, just two years after its invention.78 In addition to these information technologies, the development of improved steamships and the creation of the Panama Canal also contributed to the globalization of finance.79

As a result of these changes, a network of buyers, sellers, and intermediaries constituting a global financial market emerged for the first time by 1870. Centered in London and Amsterdam—and with important hubs in New York, Germany, and France—this system lasted until 1914.80 During these years, securities were more important in finance and investment than ever before. To quantify the extent of market participation at this time, one estimate suggests there were 20 million securities investors worldwide by 1910.81 This number is likely larger than ever before; with a world population of roughly 1.65 billion people, it represented 1.7 percent market participation, and a much higher percentage of the population in the more developed economics.

Broadening of American Stock Ownership

At the beginning of the twentieth century, only about 5 percent of households in the United States directly or indirectly owned stocks. Because brokers would only manage large accounts and execute large trades, and because stocks often had to be bought in large lots, the markets were in practice accessible only to a small slice of society. In 1912, only 60,000 traded on the NYSE, and in 1916, only 13 percent of NYSE brokers would execute trades of fewer than 100 shares.82

Though investment was not actually widespread, stock markets captured the public imagination. Large numbers of Americans mimicked investment through so-called bucket shops, which arose around 1880 and remained popular for almost 40 years. In the bucket shops, participants essentially bet on the direction in which a stock would move in a very highly levered fashion, with small changes generating large profits and losses. Rather than watching horses race around a track, bucket shop patrons got their thrills by watching ticker tapes. Such gambling allowed people without real access to the market to participate in market hysteria.83

With a bull market in the 1920s, Americans began to participate more broadly in financial markets. A recent estimate suggests that between 4 and 6 million Americans owned stocks in the 1920s, accounting for 15–20 percent of households. However, most were not active investors—about 1.5 million individuals, or 1.2 percent of adults, likely had active brokerage accounts, while others simply acquired shares through employee stock ownership plans and the like.84 Other estimates, based on federal income tax data, suggest there were 4–6 million shareowners in 1927 and 9–11 million in 1930.85 When the Great Depression hit, the broadening stock ownership of the early 1900s slowed, then stopped, then reversed. People lost trust in the stock market, and investors no longer had as much extra money available to invest.86

In 1952, the Brookings Institution conducted a landmark study of share ownership on behalf of the NYSE. The survey showed that 6.5 million Americans, or 4 percent of the overall population and 9.5 percent of households, owned stock directly.87 When restricted to adults, it showed that 6.35 million adults (6.4 percent of the adult population, or about one in sixteen adults) owned shares.88 It is important to note the study’s explicit focus on direct share ownership. It is true that most shareholdings at the time were attributable to individuals, with only 11.4 percent of shareholdings through fiduciaries and less than 3 percent of shareholdings through institutions, foundations, insurance companies, investment companies, and other miscellaneous corporations.89 However, the distinction between direct and indirect ownership is still significant. In addition to this focus, though, the study also examined the ownership of other investments, finding that 67.1 percent of individuals had life insurance, 34 percent had savings accounts, 4.2 percent had publicly owned stocks, and 1.9 percent had privately held stocks, with 78.9 percent of the population overall having at least one form of investment.90

The Brookings survey showed differences in stock ownership among segments of the American population. For example, older, more educated, and wealthier individuals were more likely to be shareholders. The number of men and women owning shares was roughly equal, at 3.26 million men and 3.23 million women, and 33 percent of shareholders were housewives. However, women likely came to be shareowners in significantly different ways than men did, with 30 percent of female stockholders stating that their stocks were “inherited or acquired as gift.”91

In the second half of the twentieth century, participation in the US financial system became more widespread. Some of the reasons for this upswing were out of the control of expert stakeholders, such as government regulators and financial professionals, and were due instead to the political and economic context of the period. For example, the long bull market following World War II made stocks seem like an attractive option for investing. In addition, the culture of the Cold War spurred the American public’s eagerness to participate in the capitalist system and to support domestic industry. In contrast to the Soviet-style economic system, in which the means of production were taken over by the state, Americans hoped to show that workers could also own the means of production through equity shareholding in a capitalistic society.92

Other reasons for increasing market participation were more carefully constructed. The development of such investment products as mutual funds, retirement accounts, and equity derivatives offered new opportunities to investors. Greater regulation made investors more trusting of the markets and more willing to invest their money in securities. The federal government implemented several regulations during the New Deal years, and the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) ushered in a new era of pension investing. Similarly, the financial industry made some of its own rules more appealing to a broad investor base. For example, commission rate deregulation allowed brokers to individually set fees charged to investors for trade execution, making stock investing cheaper for retail and professional clients alike. Finally, public relations and marketing campaigns brought the market to the masses. Charles Merrill is perhaps the best-known figure in the development of the retail brokerage industry. The NYSE was also active in promoting share ownership during this time. From 1954 to 1969, its “Own Your Share of American Business” marketing campaign attempted to attracted small investors. New York Stock Exchange president Keith Funston expressed this objective clearly in 1951: “If we pursue our objectives with the strength of our convictions, we shall eventually approach our ideal, a nation of small share owners, a nation in whose material wealth every citizen has vested interest through personal ownership, a nation which is truly a people’s democracy.”93

By the early twenty-first century, 80 million Americans owned stocks directly or indirectly, accounting for approximately half of US households.94 On the whole, then, the story of American investment in the twentieth century is one of broadening ownership. There is a much higher incidence of direct or indirect stockholding in the adult population now than there has been in the past—up from, for example, one in sixteen adults being an NYSE shareowner in 1952, to one in five in 1980, to one in four in 1990, to an impressive one in two and a half holding shares in the early 2000s.95

Many new investors, though, are not active participants in financial markets. Most American shareholders of the early 2000s held their shares through mutual funds or retirement accounts,96 and although the direct owners of most shares in 1952 were private individuals, the direct owners became, to an increasing extent, institutions and intermediaries.97 Furthermore, those who do participate directly in the stock market may participate in very different ways. In the early twenty-first century, about two-thirds of households held less than $6,000 in stocks. Many just held stocks through employee stock ownership plans, leaving a minority involved in active trading.98 Most direct shareholders also did not have diverse portfolios. In 2010, of all families with directly held stocks, 29 percent held only one stock, and only 18 percent held more than ten stocks. Of the families that held stocks directly, the median stock portfolio was valued at $20,000, while the median retirement account of families holding this asset was valued at $44,000.99

Furthermore, while in aggregate the data suggest a public that is more engaged in the financial system, a closer examination of the data shows that certain groups of Americans are less likely to hold financial assets and, even if they do hold those assets, are less likely to invest much money in them. With respect to sex, the NYSE reported from 1952 to 1983 that the difference between the number of male and female adult shareowners ranged between 5.0 percent in favor of females and 5.4 percent in favor of males. A new survey methodology introduced in 1985 seemed to show that the gap was actually quite large, with 22 and 26 percentage points greater ownership for men in 1985 and 1990, respectively. (In 1990, 30.2 million adult men and 17.8 million adult women owned stocks.100) Not all data suggest such great inequality among demographic groups, however. For example, there is a distinct trend toward ownership of stocks by younger people. While the median shareowner age was fifty-one in 1952, it had decreased to forty-three by 1990, a trend that began between 1975 and 1980.101

Consolidation

In recent years, many exchanges, generally regional and relatively small exchanges, have shut down or been absorbed by larger exchanges as competition over cost, speed, and quality of execution has grown increasingly fierce. As laid out by economists James McAndrews and Chris Stefanadis, the main advantages of consolidation are threefold: streamlined technology, increased liquidity, and reduced fragmentation. First, when different exchanges use different trading platforms, they must each incur the fixed costs associated with creating and maintaining those platforms. Furthermore, investment banks and other intermediaries must maintain connections with multiple kinds of systems, leading to heightened complexity and cost. When a regional exchange is closed and trading is moved to a national or international exchange, or when a regional exchange is acquired by a national or international exchange system and integrated into that network, the costs of proliferating technologies are reduced. Second, as more and more buyers and sellers enter a single exchange, liquidity increases, meaning there is a higher likelihood that a match can be made between a buyer and a seller at a mutually suitable price. More liquid markets are more attractive to both buyers and sellers, creating a positive feedback loop or “snowball effect,” in which the most attractive exchanges become even more attractive while the least attractive exchanges become even less attractive. Finally, exchange integration is beneficial because it reduces fragmentation of capital markets. It is inefficient to have the same stock trading at different prices on different exchanges. Under such a system, it is more difficult to discover the “true” price of a security.102

These three forces, along with some technological and regulatory changes, led to the decline of regional exchanges in the United States in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The advent of cross-country telephone service in 1915 and the creation of a nationwide NYSE stock ticker network in the 1920s ended the regional exchanges’ information advantage. In 1936, the federal government introduced unlisted trading privileges, permitting securities listed on one exchange to be traded at any other exchange. As a result of these changes, while the United States had over 100 regional exchanges in the late nineteenth century, that number had declined to eighteen by 1940, eleven by 1960, and just seven by 1980.103

Today, even the traditional giants in the stock exchange industry are subject to the forces of consolidation and technology-fueled evolution. The London Stock Exchange, for example, transitioned from a private to a public company in 2000. In 2007, the exchange merged with the primary stock exchange in Italy, the Borsa Italiana, to create the London Stock Exchange Group.104 The NYSE itself has been involved in a number of mergers and transformations in recent years. In 2006, NYSE Group Inc., a for-profit public corporation, was created after the NYSE merged with a company named Archipelago Holdings. The next year, NYSE Group Inc. merged with the European exchange Euronext to create NYSE Euronext, and this group then acquired the American Stock Exchange in 2008. NYSE Euronext itself was acquired by Intercontinental Exchange Inc., based in Atlanta, in 2013.105 There are some regulatory limits to consolidation of such larger mergers and acquisitions, however, as demonstrated when a proposed merger between NYSE Euronext and Deutsche Börse, a German exchange group, was blocked by the European Commission in 2012.106

Globalization