THIS CHAPTER TRACES THE HISTORY of more recent and more novel investment forms—specifically, the class of alternatives as well as the low-cost passive vehicles embodied in index funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). In many respects, these two forms of investment are radically different. Alternatives (a class of investments that includes hedge funds, private equity, and venture capital) tend to be high-fee, relatively exclusive, and often institutionally oriented products. Index funds and ETFs, by contrast, are low fee, typically involve passive and rules-based ownership, and are available for retail investors and institutions alike. Debates have raged over the relative superiority of these as well as the ability to combine the two classes in a diversified portfolio. Few examinations, however, have sought to uncover their respective historical developments to unlock meaning and their possible futures. This chapter aims to do precisely that, unearthing the origins and evolution of these investment vehicles.

ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS: HEDGE FUNDS, PRIVATE EQUITY, AND VENTURE CAPITAL

The realm of alternative investments is vast and includes not just hedge funds, private equity, and venture capital but also commodities, real estate, and infrastructure. These investment vehicles have captured the attention of many, fueled in great part by stories of brilliant managers and stellar returns. Undoubtedly, the awe and reverence some investors have for these sophisticated vehicles derives in part from the fact that they have long been limited to high-net-worth individual investors and institutional investors, rendering them somewhat inscrutable to the public. The truth is more nuanced.

Snapshot of Alternatives

Alternative investments have been available to institutional and professional investors since the 1970s. While the term alternative investments generally refers to nontraditional investments in securities such as equities, bonds, property, or more esoteric assets, the term is a catch-all of sorts and can refer to investments made in hedge funds, private equity, venture capital, real estate, and other financial contracts and derivatives.

Alternative investments are usually less correlated with widely used indices and other assets, and they are often illiquid, a factor most commonly cited by investment professionals and market participants in justification against investing in alternatives. However, many major investment institutions, including university endowments such as those at Yale and Harvard, have praised the net benefits of alternatives, including their hedging potential and their ability to lower the volatility of the overall portfolio. The major investment categories within the sector of alternative investments are real estate, hedge funds, and private equity. The top 100 alternative investment managers in 2011 invested 78 percent of their total assets in these three investment classes.1

Alternative investments have continued to grow in popularity since their introduction almost 50 years ago. From the mid-1980s to the 1990s, aggregate commitments to the alternatives asset class grew by over 20 percent per annum. One 1997 report in the Financial Analysts Journal corroborated a similar trend through the late 1990s, specifically among pension plans. Between 1992 and 1995, pension plans started investing a great deal more into private equity, with the more prominent funds increasing their commitments 92 percent to some $70 billion in total.2 Some of this increase can be explained by the overall growth of pension fund assets under management, from $786 billion in 1980, to $1.8 trillion in 1985, to $2.7 trillion in 1990, all the way to $8 trillion in 2004. This growth has driven interest in alternatives, given the accelerating need for adequate returns on a vastly increasing stock of investable capital.3

The last few decades have also seen the expansion of alternative investments globally. In 1992, there was only subdued interest in private equity investment beyond the United States. However, in just three years, international private equity investment grew to comprise nearly 6 percent of total alternative investments. Experts generally agree that much of the growth in international private equity can be attributed to three factors: increasing investor interest in global publicly traded equity securities, the transition from government-controlled to market economies, and the privatization of industry that accompanied this around the world.4 Accompanying these macroeconomic changes was the emulation of the structures of the private equity vehicles that had been successful in the United States. This led to the formation of large partnership legal structures around the world, many based in the United States but funded and invested all over the globe.

While the extent of institutional investors’ support for the alternative investments available in the market is clear, it is not as easy to quantitatively determine how many individual investors invest in such assets. However, there are strong indicators that traditional retail investment in alternative assets is growing, with prominent fund managers and investment directors commenting that their own clients’ perceptions are trending in this direction. For instance, bond fund manager Bill Gross asserted in 2012 that “the age of credit expansion which led to double-digit portfolio returns is over. The age of inflation is upon us.” He argued that this would lead to the exploration of alternative assets, to increase returns and combat inflation, and to stalemates in the global equities markets.5 Many fund managers do not have quite so negative a view, but they do believe that proper diversification may include capturing these asset classes.

One major barrier to traditional retail investment in private equity, venture capital, and other alternative investments in the United States involves several SEC regulations and congressional acts regarding “accredited investors,” who, by Rule 501 of Regulation D of the Securities Act of 1933, must have a net worth of at least $1 million (not including the value of one’s primary residence) or have income of at least $200,000 each year for the last two years, among other provisions, in order to invest in seed rounds, limited partnerships, hedge funds, private placements, and angel investing networks. As a result of these barriers to client acquisition, alternative investment sellers have shifted the burden of determining investment eligibility to clients themselves in most cases. Oftentimes, such notices will be accompanied by daunting caveat emptor (buyer beware) provisions warning potential investors of the inherent risks in such investments.6

All that said, the precise nature of the future of private placement solicitation rules is in flux. The JOBS Act of 2012 contained a section that broadens the ability of hedge funds to advertise to clients and lowers the standard of only speaking with accredited investors. It is up to the SEC to formulate a set of rules that is more detailed on what is permitted and what is prohibited. One of the staunchest opponents of this provision is the mutual fund industry.7 It presently enjoys the ability to advertise and is not pleased by the prospect of competition from hedge funds.

Perhaps the most prominent concern regarding alternative investment advertising is the possibility for adverse selection. Many of the best funds may orient themselves primarily toward institutions given that, compared to individuals, institutions often have longer-dated capital and better underwriting and monitoring mechanisms by virtue of having full-time staff. As such, it is possible that there may be a disproportionate representation of lower-quality hedge funds that seek to advertise broadly because they have been less successful in raising money through traditional routes from sophisticated institutions. By targeting the lower end of the accredited investor pool en masse, they may find less sophisticated investors who do not have sufficient experience to conduct proper due diligence.

Although alternative investments are traditionally regarded as any investments having lower correlations with more conventional investments such as stocks and bonds, many analysts today take issue with this description. Indeed, one instance when correlations tend to be high across all asset classes is during financial crises. First, asset prices are affected more by broad macroeconomic factors (such as monetary policy announcements, trade numbers, or employment figures) than they are by idiosyncratic, asset-specific factors. Second, during a crisis, there is often a rotation toward cash and away from risk assets that drives prices down as market participants seek liquidity. These sell-offs often happen across many asset classes during a crisis, causing correlations to spike. Alternatives broadly are not immune from this phenomenon.8 In truth, even private equity and venture capital, which do not have tick-by-tick prices, experience these declines in value as the price the companies could fetch in an exit decreases.

Having outlined this set of facts about alternatives, this chapter will now explore several of the major vehicles themselves, beginning with hedge funds. Hedge funds will be reviewed at slightly greater length, consistent both with the amount of attention they have captured and the extent of the care required for proper treatment of the subject.

HEDGE FUNDS

The hedge fund has found itself in headline after headline in recent years, and yet, the information disseminated seems to have produced little consensus on how these pools of capital have actually performed, how they should operate, and what role they should serve in both the wider financial landscape and within one’s portfolio. Indeed, some investors have decried them as underperforming following the global financial crisis of 2008, and others have lauded them for providing relative stability during this tumultuous period. Some have condemned them as easily susceptible to fraud, and others have regarded them as relatively safe as long as essential red flags are avoided. Some believe ardently that more regulation is necessary, and others see such supervision as unnecessary and inconvenient.

There are broadly two reasons for this lack of harmony in public sentiment. The first is that the hedge fund is often cloaked in mystery. Some of this mystery is self-created, since many successful hedge funds have no interest in making their investment strategies transparent to the world, lest the investments become less lucrative as others emulate them. However, much of this opacity is due to the regulatory environment that allows hedge funds to avoid certain registrations under the Securities Act of 1933 if they refrain from solicitation of unqualified investors. As a result, hedge funds sometimes appear evasive when in fact they are simply prevented from sharing particular information.

The second reason for the lack of harmony is that the very definition of a hedge fund remains exceptionally broad. As a class, hedge funds today invest in virtually every type of instrument, from derivatives to equities to corporate debt to private placements. Some funds exclusively establish long positions, whereas others complement their portfolios with short sales. Some decide to make consistent use of leverage, others make tactical use of it, and yet others avoid it entirely.

Almost comically, perhaps the most commonly shared feature among hedge funds has nothing to do with what hedge funds actually do. Rather, the most consistent element is how they charge clients for their services. Many hedge funds charge a combination of an asset management fee (most commonly a 1–2 percent fee on the total asset base, largely invariant with how well the fund does) and a performance fee of 10–20 percent of the returns of the fund above a high-water mark.9

Given this ambiguity and reticence, it is not easy to conduct a penetrating analysis on this investment vehicle. However, the questions posed are crucial: where did they come from, how justified are their fees, what are the various strategies employed, what common features do the outperformers have, and what does their future look like? With some persistence, though, these informational limitations can be overcome to generate satisfying answers.

The Origin of Hedge Funds

When it was conceived, the hedge fund was a far more specific and well-defined instrument than it is now. It was a fund that made use of “hedges” and, in fact, was termed a hedged fund.

The first hedge fund had a somewhat unlikely founder in Alfred Winslow Jones. Educated at Harvard as an undergraduate, he subsequently served in the American embassy in Berlin in the 1930s and later spent time in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. He went on to Columbia as a doctoral student in sociology, and after graduation in 1941, he turned his thesis into a book, Life, Liberty and Property: A Story of Conflict and a Measurement of Conflicting Rights. A passion for finance did not seem to manifest itself until Jones became a writer at Fortune magazine during World War II and eventually began to write about financial forecasting.10

It was through research for his financial articles that Jones came to the realization that one need not be fully exposed to the directionality of the market to produce returns. In fact, Jones thought he could produce more attractive returns by avoiding full exposure. He decided he would buy stocks he deemed to have compelling risk-reward characteristics and he would sell short stocks that were unappealing and overpriced. Jones was not typically completely beta neutral—selling short a volatility exposure that precisely matched the magnitude of his long positions—but he did use shorts to shave off some of the directional risk. In effect, Jones had constructed a long-short hedge fund.

In terms of operational control, Jones left the actual stock selection to managers he brought in to oversee portions of the portfolio.11 These internal managers were given significant autonomy and were permitted to prepare the orders for execution. Once either Jones or his second in command took a look at them, they were given the green light. Jones did not use particularly active investment committees.12 Meanwhile, Jones gave himself the higher-level task of trying to ensure that the managers were successful and determining if the entire portfolio was well diversified.

In return for his services, Jones charged his clients a performance fee that would eventually become the norm: 20 percent. He justified this number by referring to the Phoenician captains who took for themselves 20 percent of the gains from profitable journeys.13

The Growth and Development of the Hedge Fund

Two transformative changes to Jones’s notion of a hedged fund followed rather quickly as a few other players joined the field. First was decreasing use of the hedge in the years that immediately followed. The reason was practical: the equities markets moved swiftly upward in the early 1960s and again in the mid- to late 1960s. Many managers saw their short positions as weighing down outsized returns on their portfolios.14 In fact, many of Jones’s own portfolio managers (who, unlike some of his competitors, continued to use shorts) remarked that it was much harder to find appealing short opportunities than it was to uncover alluring long positions.15

The second change introduced was leverage, and it was used for precisely the same reasons: to capitalize on the powerful upswings in the markets at the time. Gearing up the long bias via leverage proved crippling for a number of funds during the down markets of 1969, 1973, and 1974.16 Some funds that utilized the most generous leverage were purged from the system. Many were caught in precisely the market-wide downdrafts that Jones’s hedges were designed to mitigate.

Throughout this period, hedge funds did not attract much public interest. Indeed, an article appearing in a 1966 publication of Fortune, where Jones had previously been employed, was aptly entitled “The Jones Nobody Keeps Up With.” The obscurity certainly was not for lack of performance: in the ten years leading up to the article’s publication, Jones racked up total gains of 670 percent.17 The paucity of public interest is attributable in part to just how small the universe of hedge funds was at the time. Even by 1984, the total number of hedge funds numbered in the sixties, and it was not really until the 1990s that the world of hedge funds began to flower.18

As the successes of hedge funds mounted in the 1990s, public interest finally picked up. One such successful fund was Julian Robertson’s Tiger Fund. While Robertson’s funds famously closed in 2000—his strategy of picking the best 200 firms to go long and the worst 200 firms to go short did not fare well in the distorted equities market of the tech bubble era—for years many regarded him as a wizard of financial markets. Other funds that gained media attention were much more exotic. For instance, the Quantum Fund, run by George Soros, gained high visibility when it “broke the Bank of England” by capitalizing on its expectation of a revaluation of the pound sterling.19

Indeed, for some of these funds, the more exotic nature of the vehicles they traded seems to have inspired a sense of awe. After all, stock selection within a hedge fund like Jones’s did not look much different than stock selection within a mutual fund, with the major functional difference being the long-short approach. But with foreign exchange and derivatives, there was a sense of esteem for those who could monetize on far less comprehensible investments.

One overlooked contributor to the rise of the hedge fund and the rise in interest about hedge funds is the computer. The computer gave financial practitioners access to a wealth of information and data that was previously rather intractable to synthesize and without which it was virtually impossible to test rigorous models. Further, the very notion of a quantitative fund—a “quant” fund—or a quantitative strategy is simply inconceivable without the computer. Without the aid of the computer, one could not construct and back-test robust models or even generate signals where certain criteria were met.

The Hedge Fund Universe Today

As of 2014, the hedge fund industry had approximately $2.5 trillion in assets under management. Additionally, approximately $455 billion was in funds of hedge funds, a diversified investment vehicle designed to add value by selecting and overseeing other hedge fund managers that generate alpha.20 Before discussing these funds of funds in more detail, let us consider the various strategies of individual funds. Despite the difficulty of categorizing hedge funds based on their strategies—many funds deploy a variety of approaches—the following list gives a broad overview of the relative composition of approaches.

ASSETS UNDER MANAGEMENT IN 2014

| Hedge Funds |

$2508.4 Billion |

| Funds of Funds |

$455.3 Billion |

| SECTORS: |

| Convertible Arbitrage |

$29.5 Billion |

| Distressed Securities |

$184.9 Billion |

| Emerging Markets |

$277.6 Billion |

| Equity Long Bias |

$203.8 Billion |

| Equity Long/Short |

$202.3 Billion |

| Equity Long-Only |

$132.5 Billion |

| Equity Market Neutral |

$42.6 Billion |

| Event Driven |

$291.2 Billion |

| Fixed Income |

$396.7 Billion |

| Macro |

$204.0 Billion |

| Merger Arbitrage |

$30.4 Billion |

| Multi-Strategy |

$273.8 Billion |

| Other |

$96.6 Billion |

| Sector Specific |

$142.5 Billion |

Today Jones’s true market neutral, long/short style makes up only a fraction of hedge fund assets under management.21 A closer look at some of the strategies can help illuminate the full range that hedge funds currently cover.

Merger arbitrage involves going long the equity of a firm that is the target of an acquisition attempt (and typically going short the acquirer as well if the acquisition is done for stock). Effectively, it represents a bet that the acquisition or merger will overcome any issues relating to shareholder approval, regulatory acceptance, and buyer financing. The merger arbitrageur collects a spread if the deal does ultimately close and takes the risk of loss if the acquisition does not receive approval or cannot be financed. This strategy can be attractive from a portfolio diversification standpoint, since the approval of a single transaction has little correlation to the market.

Event-driven strategies look for hard catalysts, or direct precipitators of asset price changes, most typically by explicit acts of a corporation’s management or board. Such strategies may include capital structure arbitrage, where a hedge fund may analyze a firm, decide the firm is at great risk of bankruptcy, and invest along the capital structure accordingly. For instance, in a distressed situation, the hedge fund may determine that a corporation will have sufficient assets to pay the senior debt holders but that there will be minimal residual value left for the equity; the fund would then establish a long position in the senior debt and a simultaneous short position in the equity, expecting a bankruptcy to precipitate a revaluation of the different classes of securities and thereby creating a profit for the fund.

Convertible arbitrage is a strategy that generally attempts to be market neutral by buying long securities that are convertible to stock (convertible debt that has a coupon payment but also has an option to become equity at a predefined conversion factor) and selling short the equity. This strategy seeks to monetize on the fact that many of these convertible instruments offer less risky exposure to volatility. The strategy, however, is certainly not without risk. One of the most well-known disasters in the history of the approach involved securities of General Motors in 2005 and was precipitated by the confluence of two major events. In May 2005, Kirk Kerkorian made a tender offer for the equity of General Motors, offering about 15 percent above the previous day’s close. The very next day, S&P issued a downgrade on the debt of General Motors.22 This caused convertible arbitrage investors to endure losses on the equity side (which they had shorted), but also on the debt (which they were long).

Fixed income hedge funds differ fairly widely in the riskiness of the strategies employed. Some are rather risk averse, seeking to buy attractive debt securities that deliver healthy and uninterrupted payments. Others have far more complicated schemes to garner returns, such as exploiting aberrations in yield curves. This can occur when the yield curve adopts an unusual geometry (often a flat or steep slope at the extreme) and managers place long and short positions that profit when the yield curve shifts. One of the most common fixed income strategies is the “swap spread,” which involves collecting the difference between Treasury rates and the swap rate. Others invest in mortgage-backed securities, like those packaged by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Macro hedge funds seek to anticipate major structural changes in an economy, either because of natural market forces (perhaps the market is grossly overheated and is due for a correction) or because of political circumstances. John Paulson of Paulson & Co., for instance, cashed in on the events that led the US economy into crisis by short selling subprime mortgage–backed securities. Because they seem to be predicting the future, many of the most successful macro hedge fund managers find themselves propelled meteorically into fame. However, there are abundant examples of macro managers who experience stumbling blocks to their prescience. John Paulson himself, for instance, experienced very poor returns in one of his funds in 2011, prompting some to question the persistence of the returns in the years that immediately followed.23 Other macro managers—like Louis Bacon, who generated substantial returns in 1990 with a thesis that Saddam Hussein would attack Kuwait but that this would have minimal long-term effect on the market—found it difficult to maintain returns. Bacon announced in 2012 that he would be returning about one-quarter of his assets under management (or about $2 billion) because he found it too difficult to generate returns, given the magnitude of governmental intervention in the wake of the financial crisis. Some have cited this as a “victory of sorts for the technocrats” who were managing the governmental response to the financial catastrophe, and in many ways, these commentators are right.24 This sheds light on another challenge of macro investing: the shifts that produce some of the most lucrative macro trades are typically quite extreme. Indeed, it is no surprise that managing a macro-oriented portfolio and having consistent success is no easy task: the identification of a string of exceptional shifts is what separates the one-hit wonders from the macro titans.

Relative value funds can encapsulate several different strategies. Some are engaged in what has been termed pairs trading, or the purchase of one security that has been deemed “cheap” on a relative basis and the sale of another that seems correspondingly “expensive.” Relative value funds profit when the prices of the pair of securities readjust. Some funds use statistical arbitrage, often examining the behavior of the time series and making judgments as to relative value based on historical valuations. Others are more fundamentally oriented, believing that one well-positioned firm will outperform a competitor. The other common strategy employed by relative value funds is seeking value across the capital structure of a publicly traded firm. By way of example, a relative value fund may believe a publicly traded company will experience severe distress in the next six months. The fund may anticipate that the stock will be worthless when this distress comes, so it shorts the stock; but the fund may still believe that the senior debt is an attractive buy, as it may not be impaired because the firm’s assets cover this tranche of debt. The fund would thus find relative value by being short the stock but long the senior debt.

Quant funds use quantitative factors in models to develop, buy, or sell signals for stocks, commodities, or currencies. These models have a wide spectrum of sophistication. Some of them are simple, trying to capitalize on well-studied sources of risk premium in the stock market like momentum, value, and small market capitalization. Others are more complicated, analyzing convergence-divergence patterns, steepness or flatness of yield curves or futures curves, or even sifting through press releases and conference calls for information on a stock that the market has neglected. The quant fund faces a few difficulties that the best groups are able to overcome. The first is to ensure that the models are not overfitted to historical patterns. In other words, if a strategy is designed or tweaked using historical price behavior, there is a temptation to retrofit a strategy that worked well in the past but may not be capturing the underlying dynamics that would cause it to be successful in the future. Second, no quant strategy, no matter how successful, will work in all market environments. There are many that work very well in certain market environments, but none that are foolproof all the time. The complication this creates is that if a given quant strategy is not working for some time, it is difficult to discern whether that strategy is failing to work because of short-term conditions in the market that may change or because there is actually a fundamental flaw in the model. It requires patience and resolve to ride out difficult market environments and await a market regime in which the strategy will prosper. Third, some, though not all, quant strategies deliver fairly small risk premia. Few quant strategies can deliver eye-popping returns on an unlevered basis. This means that many quant funds employ leverage to make returns more attractive. When prudent, this leverage can be perfectly acceptable, but it can also materially impair a fund if a strategy or set of strategies does poorly.

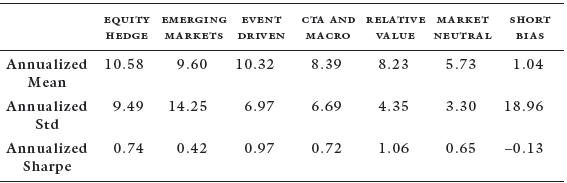

Given these myriad strategies (and many more not elucidated here), the natural question that follows is, which strategies are most successful? This is an enormously difficult question to answer, as one should really assess funds based on alpha and not simply returns. Furthermore, the best performers do change through time, since the market does not reward the same strategy all the time. That said, to provide some empirical insight on the matter of the more recent performance of these strategies, the aggregate risk and return figures from 1994 to 2011, assembled by KPMG and the Centre for Hedge Fund Research (table 8.1), show that relative value and event-driven funds have been the strongest performers on a risk-adjusted basis (as measured by their Sharpe ratios).25

TABLE 8.1

Statistics for Hedge Fund Strategies

Source: Robert Mirsky, Anthony Cowell, and Andrew Baker, “The Value of the Hedge Fund Industry to Investors, Markets, and the Broader Economy,” KPMG and the Centre for Hedge Fund Research, Imperial College, London, last modified April 2012, http://www.kpmg.com/KY/en/Documents/the-value-of-the-hedge-fund-industry-part-1.pdf, 11.

TABLE 8.2

Venture Capital Firms

| |

1991 |

2001 |

2011 |

| No. of VC Firms in Existence |

362 |

917 |

842 |

| No. of VC Funds in Existence |

640 |

1,850 |

1,274 |

| No. of Professionals |

3,475 |

8,620 |

6,125 |

| No. of First Time VC Funds Raised |

4 |

45 |

45 |

| No. of VC Funds Raising Money This Year |

40 |

325 |

173 |

| VC Capital Raised this Year ($B) |

1.9 |

39.0 |

18.7 |

| VC Capital Under Management ($B) |

26.8 |

261.7 |

196.9 |

| Avg VC Capital Under Mgt per Firm ($M) |

74.0 |

285.4 |

233.8 |

| Avg VC Fund Size to Date ($M) |

37.4 |

95.4 |

110.6 |

| Avg VC Fund Raised this Year ($M) |

47.5 |

120.0 |

108.1 |

| Largest VC Fund Raised to Date ($M) |

1,775.0 |

6,300.0 |

6,300.0 |

By contrast, short bias funds have tended to have the least attractive risk-reward characteristics, returning just over 1 percent per year but having the highest volatility of any of the categories listed. Much of this is due to the strong bull market of the 1990s and the run-up again in equities markets between the technology bubble and the global financial crisis. Timing shorts, as Jones himself found decades ago, is quite difficult. After all, if one’s premise is that an asset is irrationally overvalued, it can be years before the market realizes its irrationality and trades the asset down accordingly. A short position may be sound, but it may be far ahead of its time, and one runs the risk of ever-increasing exuberance and the erosion of value by borrowing costs.

Characteristics of Strong Performers: Size and Age

Given this state of affairs in aggregate, another question is whether there are particular characteristics that are shared among the hedge funds that deliver persistent good returns. After all, an investor does not necessarily care if hedge funds, in aggregate, do not provide positive returns net of fees, as long as he or she is able to identify those that will.

One surprising finding, supported by a number of successful papers, is that smaller hedge funds tend to have better persistence of favorable performance than do larger funds. One study that has examined this has used the Lipper TASS database and looked at data from the late 1980s, including funds that continue to operate and those that have since closed. The study took pains to eliminate the backfilling of the database that can drive significant upward bias in aggregate returns. The finding is not that younger funds are explicitly better in terms of returns, but rather that of the funds that have a positive track record, the funds more likely to have those positive returns persist into subsequent years tend to be smaller. This finding does not seem to hold strongly for funds of funds.26

There are a number of causes that could explain this trend. The first and most apparent is that some small managers know a corner of the market so well that they are able to find inefficiencies easily, but that scaling up leaves them with more capital than they are able to successfully allocate. Second, it could be that some hedge fund managers are very good investors but are less successful at managerial tasks, so the organization itself is unable to scale appropriately. Further research is certainly needed to help determine why exactly small funds tend to have more consistent positive performance.

Funds of hedge funds—which hold a portfolio of hedge funds rather than investing directly in underlying securities—may have several notable advantages over individual hedge funds. The first and perhaps most pronounced is their ability to diversify across a range of hedge funds and strategies. In the absence of a fund of funds, achieving diversification can be elusive except for the exceptionally wealthy, since many of the best funds have fairly high investment minimums.27

Another important but less crucial factor is access to the most adept managers, which can come in two forms. One way is by identifying funds with good managers already in place, doing so through meeting with the managers periodically, determining if they are actually producing alpha by comparing returns relative to benchmarks, and conducting assessments not only of a fund’s investment process but also of its business organization. This groundwork is crucial, since a hedge fund with material key man risk, difficulty in managing employees, or disagreements among partners over where the firm should be headed may see returns suffer in the long term. It is the job of the fund of funds to look at factors that could adversely affect their own investors but may not be completely obvious in quarterly letters or other investor communications. Second, some funds of funds have access to highly successful managers whose funds may be closed to further investment.28 Sometimes, hedge funds close to new investment because managers have determined they would simply have too much capital for the given opportunities to exploit inefficiencies in the market. Although this decision may seem counterintuitive, it follows an often quite rational path. After all, while new inflows can increase the total earned on the asset management fee (the fixed fee on the total capital invested), they can also put the fund over its practical capacity, with returns suffering as a result. Funds of funds that have already invested in closed funds can provide additional slivers of exposure to otherwise inaccessible managers.

That said, the fund of funds structure is not without its disadvantages. For instance, at a certain scale, a fund of funds might be better off bringing certain strategies in-house by hiring managers directly and saving on fees. This would also grant the fund of funds the ability to scrutinize the trades directly and might support better control over liquidity and risk.29 Indeed, there are some funds pursuing this hybrid strategy, with internal capabilities as well as an external platform to hire managers to invest in niche strategies that cannot be executed successfully in-house. Some university endowments, such as Harvard Management Company, pursue such a hybrid strategy, keenly aware that there is logic to keeping much of its portfolio in-house.

There is a second, more complex drawback of funds of funds—one that, somewhat ironically, becomes worse the more diversified the fund of funds becomes. In any given year, some strategies will be successful and some will fail, but a diversified fund of funds must pay performance fees on the strategies that are successful even if, in aggregate, the fund of funds does not have a positive return. Fortunately, this problem with performance fees does decline the longer a fund of funds is invested in its particular hedge funds, as funds must overcome their high-water marks in order to charge the performance fee.

The third and perhaps most important disadvantage is the simple fact that a fund of funds must clear two layers of fees: its own fees and the fees charged by the hedge funds in which it is invested.30 This means that the value added by fund of funds managers must be fairly significant for this to be a better enterprise than investing directly through underlying vehicles. Fortunately for funds of funds, empirical research shows that these managers have indeed succeeded. One study draws data from a combination of two databases (the TASS and the HFR) and performs an analysis of funds of funds over an eight-year period. The study concludes that, in fact, funds of funds do succeed, in aggregate, in adding value net of fees. Equally interesting, however, is the performance attribution: the funds of funds are successful because of sound strategic asset allocation rather than tactical asset allocation. In fact, the study finds that on average, the tactical asset allocation seems to add zero or negative value in most years, though part of this may be due to the underlying managers’ liquidity constraints (a fund of funds cannot reallocate funds immediately, since the funds are often at the whim of redemption windows).31

Illiquidity of the Vehicle

Hedge funds are less liquid than many other investment vehicles available in the market. Investors are often faced with initial investment lock-ups (intervals of time during which they are unable to withdraw), and even after the lock-ups, investors subsequently face specific redemption windows during which they can elect to withdraw funds.

Taking advantage of the intrinsic illiquidity of the vehicle, some hedge fund managers position the portfolio to earn an illiquidity premium, or effectively, a return that is due to holding assets that cannot be rapidly sold without affecting the market price. In cases like these, unless it is clear to investors that the hedge fund is investing in illiquid products and earning a return on illiquidity itself, it may appear that the managers are producing more alpha than they really are. Also, this illiquidity premium may be perfectly acceptable for funds that experience large net inflows of capital over time as new investors pour in, but it may devastate a fund that experiences a large flurry of redemptions and is forced to sell in high-illiquidity situations. This can be mitigated if funds have “side pocket” capabilities (that is, redemption requests involve transferring the investor’s share of the illiquid assets rather than selling and redeeming as cash) or gates the fund can use to slow down large redemptions at a distressed period. Indeed, one study has found that funds with a large net inflow of capital and with significant exposure to illiquid products outperform low-net-inflow funds by about 4.79 percent per year.32

This situation is seen more readily in funds that trade distressed credit, convertible debt, or other derivatives that have shallow markets or that hold private investments in addition to their public market activities. Long-short equity funds, by contrast, do not generally have this liquidity problem unless they deal with very low market capitalization or low-turnover stocks. So to some degree, the type of fund can shed light on how likely it is to benefit from the illiquidity premium. Whatever the case may be, investors must be aware of how changes in inflows could affect performance and how much of the performance could be due to the illiquidity of the market rather than the value-add of the manager.

Risks and Returns

One phenomenon that has been documented in the mutual fund literature but also likely holds for hedge funds is the increase in assumed risk during periods of underperformance. Researchers have found that many mutual funds that are underperforming within a year tend to take more risk before the reporting period is through, ostensibly in hopes of making up for the losses. One study with high statistical significance has looked at 334 growth mutual funds from 1976 to 1991 and found that volatility increases when performance is negative within a period.33 It is not necessarily the case that these managers are being deliberately dishonest; they likely feel genuine responsibility to add value for investors. However, the way they go about it—by taking on more risk than usual—can prove even more injurious.

To be clear, one can only speculate that this is true for hedge funds, since we do not have the benefit of daily return data to actually measure volatility. But there are two good reasons to believe it might be the case. First, hedge funds often have the added benefit of not revealing the extent of the risks they took in the period, so their behavior is much more difficult to monitor. (With open-ended mutual funds, by contrast, one can simply take the standard deviation of the daily returns to calculate volatility and have a good proxy for risk.) Second, whereas the returns to a mutual fund benefit the mutual fund manager only indirectly (as higher returns often translate into higher net inflows and thus increase the asset management fee), the hedge fund manager earns a performance fee when returns are good. So hedge fund managers may have an even stronger temptation to make riskier moves toward the end of a bad period, given that this behavior will not be immediately apparent and that the payoff could be significant.

One final observation pertains to the difference between dollar-weighted and buy-and-hold returns. The returns one almost invariably sees from hedge funds are buy-and-hold returns, which operate on the assumption that the total dollars given by an investor to the fund does not change over time; that is, investors do not later decide to add more money to their position or, alternatively, withdraw existing investments. This can lead to the conclusion that hedge funds have generated more wealth than they actually have, given the reality that capital inflows tend to increase in the period after good returns because investors think the returns will persist into the future.34 Likewise, funds often experience outflows after poor performance, so the dollar-weighted returns can be much lower than buy-and-hold returns if performance reverts to the mean.

Some studies have highlighted the fact that the harm to the hedge fund vehicle was likely far greater than it appeared in the global financial crisis, as capital deployed to hedge funds was at its maximum in 2007. As a consequence, the dollar-weighted losses were more significant than the buy-and-hold return metrics make them seem. Studies that attempt to measure how divergent buy-and-hold return measures are from dollar-weighted returns for hedge funds show that dollar-weighted returns tend to be 3 to 7 percent less than buy-and-hold returns per year (with the precise value naturally contingent upon the interval of time one chooses to analyze).35

Ultimately, the hedge fund is a much more complicated vehicle than is widely appreciated. This group encompasses a plethora of different strategies offering different risk and return characteristics. Although there are plenty of hedge funds that have performed terrifically, “tales” of truly phenomenal returns across the entire universe of hedge funds are precisely that: elusive fictions that are the result of generalizing the performance of a small class of stellar investors.

PRIVATE EQUITY, VENTURE CAPITAL, AND OTHER ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS

Next, we turn to the fields of private equity, venture capital, and other alternative investments. Just as larger institutions, investment banks, and wealth management divisions within private banking bodies primarily drove the world of investment management before the mid-twentieth century, the twenty-first century has been dominated by a wide range of alternative investment possibilities for both institutional and, to a lesser degree, individual investors.

Private Equity

Private equity, in the traditional sense, involves either purchasing or creating private companies with the goal of eventually selling to a strategic buyer, selling to another private equity firm, or listing the firm on public markets. A relatively new industry, it came to its current state only after a rollercoaster ride in the late twentieth century.

Central to the development of the early private equity market in the United States was a small firm founded by Georges Doriot (a professor at the Harvard Business School), Ralph Flanders (an industrialist and later a senator), Karl Compton (a president of MIT), Merrill Griswold (head of the Massachusetts Investments Trust), and Donald David (a dean of Harvard Business School). Established in Boston in 1946, it was called the American Research and Development Corporation, or ARD. In the wake of World War II and in an economy that had recently experienced a large upward shock in labor supply when millions of veterans returned from the war, ARD focused on both providing capital and enhancing the managerial skills of businesses.36

The corporation primarily sought institutional capital rather than capital from retail investors and as such was relatively unique in the asset management industry for at least a decade. It was successful in investing in a wide array of companies before ultimately merging with Textron in 1972. However, it was in the 1970s, when the first major shift in government regulations and investor perceptions of private equity funds occurred, that the industry really took off.

The regulatory change was prompted by the government’s realization that there was a dearth of capital in private equity. So the Small Business Administration reexamined existing regulatory provisions and decided to try to reinvigorate private equity and venture capital deals by restructuring certain securities laws and rewriting the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. Between 1970 and 1980, and especially in the year 1980 alone, regulatory constraints were widely removed. For instance, the Department of Labor changed a provision that previously necessitated many private equity managers to be registered investment advisers. Further, in 1980 some private equity companies were recategorized as business development companies and thus were no longer required to comply with the Investment Advisers Act. This act had effectively limited private equity partnerships to fourteen partners; the rule change allowed private equity partnerships to grow without bound.37

With these key barriers to private equity market entry removed, the industry exploded. It happened almost immediately, with total commitments to private equity over the three-year period from 1980 to 1982 well over twice the total commitments throughout the decade before.38 However, this seemingly unstoppable increase in the amount of private equity investment was not without considerable volatility. One reason for this was the surge in leveraged buyouts. Leveraged buyouts are a prime example of using leverage to improve returns on investment and typically involve taking a public company private. They are also characterized by a reliance on high amounts of leverage placed on the balance sheet of the firm being acquired. After deals are closed, private equity operating managers take over control of the portfolio companies and do not have to concern themselves with public company reporting requirements. The private equity firm can institute organizational changes, including strategic reorientations, personnel changes, and mergers with or acquisitions of other firms with the goal of achieving a future exit at a multiple of the original capital invested. The idea of the leveraged buyout was arguably thought of much earlier, by J. P. Morgan & Co. in 1901 when Morgan bought the Carnegie Steel Corporation for $480 million. The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 virtually regulated away merchant banks like Morgan’s by not allowing depository banks to act as investment banks.39

One of the first private equity firms of the post–World War II era was Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, or KKR, founded in 1978 by partners who left New York investment bank Bear Stearns. In 1988, KKR won the bid for the largest leveraged buyout in investment history to that point—that of RJR Nabisco for $25 billion, a storied investment transaction famously chronicled in the book Barbarians at the Gate and the film of the same name.40 These firms of the 1980s were the first in the private equity world to use modern techniques of leverage, high-yield bonds, dividend recapitalizations, and new capital structures that have become so prevalent in the private equity world today. The inventiveness of the partners of the first movers in this industry allowed them to reach new levels of success and rewards.

However, while the significant use of borrowing is a vital component of the high return historically achieved by many private equity funds, it can also lead to serious shortfalls in outcomes when operations or the economic environment fail to unfold as expected. Indeed, from 1982 to 1993, the huge increase in high-yield and low-quality debt offerings led to substantial problems in the private equity industry.

The effect, though, was cyclical, and as the early-1990s recession led to undervaluation in the public equity markets, institutional private equity firms gained prominence and the industry was once again on an upswing—until, at the turn of the century, the technology bubble burst. This was followed by yet another upswing that culminated in, and contributed to, the 2008 financial crisis. Because many leveraged buyout private equity firms have performance that is intimately tied to public equities markets—after all, many of the exits are to the public markets through initial public offerings—it is not surprising that there is cyclicality in commitments and activity as the stock market experiences peaks and troughs of its own.

Since the 1980 boom in industry assets under management, the returns from the major private equity firms’ funds have been considerable. That experienced fund managers could achieve consistent double-digit returns attracted investors and scholars alike. Some industry proponents continue to predict that with proper operational management and investment discipline, the successful major private equity fund managers may be able to achieve annual rates of return above 20 percent in the decades to come. However, some critics caution against being as bullish on private equity as an industry. Many believe instead that there is enough new competition in the realm of buyout private equity that the days of firms earning substantial premiums over the market may be largely over. What was once an exclusive and off-the-run asset class has seen much broader participation, and with it, the possibility of lower future expected returns in aggregate.

Venture Capital

Venture capital is really a subset of private equity, and the early history of venture capital goes hand in hand with the history of private equity. Venture capital tends to deal with high-risk, growth-oriented firms, often those in the various tech industries: information technology, biotechnology, energy technology, and computer technology. These venture investments frequently involve allocating capital to technologies that have yet to be proven or for products without an existing or well-defined market. Other industries, too, have historically been recipients of important venture funding. Starbucks and Federal Express, for instance, were capitalized early on by venture investors. Their success, while astounding and impressive today, was far from certain when the firms were in their infancy.

But it really was the technological revolutions in the twentieth century—opening the way for the development of powerful advances in computational power, medicine and health care delivery, data processing and analysis, and electronics, among other sectors—that spurred this new kind of investment as venture capitalists jumped at the opportunity to monetize many of these nascent industries.

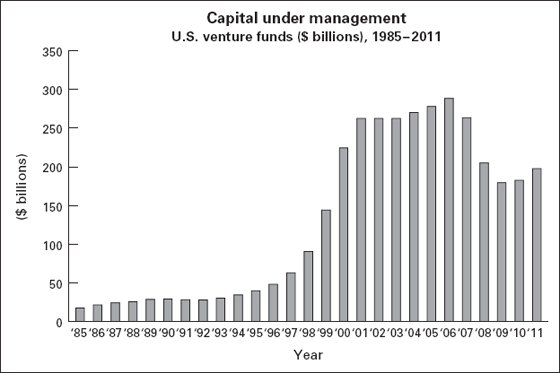

It took several decades after the creation of the Small Business Act of 1958 for venture capital to really take off. Difficult conditions in equities markets, combined with a more complicated and expensive listing process, produced a barrier to initial public offerings, frequently the ultimate exit of a venture deal.41 The National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) was founded as an industry association in 1973, and over the next several decades the dollar amounts flowing into venture capital as an alternative investment class ballooned significantly (see figure 8.1 and table 8.2). The industry is now seen as a leading alternative investment class for institutional and high-net-worth investors looking for ways to diversify their portfolios.

Figure 8.1 Capital Under Management U.S. Venture Funds (Billions), 1985–2011

Venture capital is intimately tied to Silicon Valley in the San Francisco Bay area. This area—blessed with a confluence of some of the world’s top research universities and technology companies—was a natural place for the venture capital industry to emerge and grow, given the initial near-synonymy of venture capital firms with technology. The first Silicon Valley initial public offerings were of Varian in 1956, HP in 1957, and Ampex in 1958. Sand Hill Road, in Menlo Park, California, became the hub for venture capital institutions, with today’s quite recognizable firms (Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers) coming to life in 1972. Furthermore, California has almost four times more venture capital–backed companies than any other state, with a focus in all sectors, but especially consumer Internet.42

Compared to venture capital investment in the United States, the amount of venture capital funds invested in other areas of the world does not reach the same level. For instance, Chinese venture investors in 2011 raised $16.8 billion, whereas US venture investment stood at $28.7 billion in 2011.43 Furthermore, there are far more venture capital firms in the United States than anywhere else, with 770 as of 2014 compared to 50 in Canada, 75 in the United Kingdom, and 87 in China.44

From the venture capitalist’s perspective, the economic alignment of the firm and its institutional investors with the entrepreneurs who are taking financing from venture capital firms is important. Such firms will often take seats on the boards of directors of the start-up companies they finance in order to play a key role in the guidance and development of the companies, to protect their investors’ capital, ensure its best utilization, and be in a position to maximize return on investment. The investors in large venture capital firms are primarily institutional, though in recent years more and more funds are opening up for investment by high-net-worth individuals.45 Like private equity, venture capital is a relatively illiquid asset class. Many firms have limited tangible value, and the ability to actually monetize on a venture capital investment depends, in large part, on successful growth of the firm.

Overall, venture capital is a significant subset of private equity investment in the United States and is a primary component of the alternative investment sector. The lucrative returns on the stellar growth companies that eventually have successful exits through acquisition by larger, more established firms or to the public through initial public offerings are what continue to attract investors to the industry. However, in recent years, critics and industry experts worry that declining returns, uncertainty regarding the existence of another technology asset bubble, and speculation regarding the level of market saturation in consumer Internet companies may all cause capital outflows in coming decades. Only time will tell.

Real Estate

Real estate products are a crucial part of the alternative investment landscape. Key among real estate products are real estate investment trusts, or REITs. These trusts were effectively created in 1960, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Cigar Excise Tax Extension bill that was sent to him by the US Congress. Originally, they were created to make a liquid and tradable form of real estate that could be accessed by not only large institutional investors but also retail investors with fewer resources. Much like today’s REITs, the original trusts would accumulate capital from many sources, including debt from institutions and banks as well as equity sales, and then act as lenders to construction companies and real estate developers. Real estate investment trusts are quite versatile within the sector, being able to encompass commercial and residential categories as well as timberland, health care, real estate, and other buckets. In 2003, there were 170 REITs (134 of which traded on the New York Stock Exchange) valued at a combined $310 billion.46

Although liquid real estate vehicles, such as REITs, are extremely popular among investors, there are clear preferences among types of products. In one industry survey, some 68 percent of advisers responding said they had invested in such vehicles, but only 33 percent of them used nontraded REITs in their clients’ portfolios.47 This shows that liquidity preference, transparency, accountability, and ability to hold to a strict regulatory standard while still being able to achieve high risk-adjusted returns are important characteristics for investors in their alternative investment patterns.

In many ways, though, REITs and their publicly traded shares are not much different than more traditional public companies—they just happen to be in the business of financing real estate and have a different wrapper and management structure around the assets. They do have some favorable tax advantages, including avoiding taxation at the trust level if more than 90 percent of the income is distributed to unitholders. Compared to other classes of traditional and even alternative investments, real estate products and REITs are characterized as having relatively high yields, hence their inclusion in many alternative investors’ portfolios.

Other Alternative Investments

Before completing the discussion of alternative investments, it is worth discussing a few other major categories, including commodities and natural resources, timber, agriculture and farmland, infrastructure, and currency.

COMMODITIES AND NATURAL RESOURCES

Investment in commodities and natural resources grew significantly in the twentieth century. One of the earliest commodities indices, the Economist’s Commodity–Price Index, was first published in 1864 and has continued publication for over 150 years now. This index, however, was among the first generation of commodities indices and was not investable, as it tracked spot prices for commodities and not real market bid-ask matches. Actual investable commodities indices are far more recent, coming into existence in 1991 with the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (S&P GSCI) and later in 1998 with the Dow Jones UBS Commodity Index.48

Commodities and natural resources investments include both traditional futures and collateralized commodity futures, as well as direct holdings of physical assets such as gold and other natural resources. Mineral rights and the licensing of revenue streams are also examples of real-world commodities and natural resources investments in the alternatives space. Commodity investments are an attractive way to diversify portfolios because they often have high returns and low correlations to equities and other liquid investable assets.49

TIMBER, AGRICULTURE, AND FARMLAND

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 was a major catalyst for investment in timberland, since pension funds now had the ability to move into new and more esoteric asset classes.50 Since the mid-1980s, institutional assets invested in timber have grown dramatically, from $1 billion to more than $50 billion.51

Asset returns were strong through the 1980s to the 1990s, resting in part on Japanese demand and pricing. Returns were helped again by the national forests reducing their output. These reductions in output were driven in large part by legal challenges around environmental concerns, including the destruction of the habitat of the endangered spotted owl. Institutions increasingly became owners of timber, purchasing from operators and owners in the foresting industry.52

Farmland (the land itself) and agriculture (the productive activity conducted on that land, such as the planting and harvesting of crops and grazing of livestock) are in much the same category. With most of the capital asset value deriving, likewise, from the real estate involved in these sectors, the history of alternative investment in agriculture and farmland is closely tied to the history of alternative investment in real estate, as discussed previously.

INFRASTRUCTURE, FIXED INCOME, AND OTHER ALTERNATIVES

Investments in infrastructure projects, around the United States and the world, are a small piece of the alternative investment asset class. These can take the form of investments by retail and institutional investors in listed infrastructure equities, which may be publicly traded, master limited partnerships, and open-ended funds.53

These infrastructure projects are often directed by local, state, or even the federal government. Consequently, one way in which infrastructure projects might find their way into an investor’s portfolio as an alternative asset class investment is through government-issued fixed income securities such as sovereign debt or municipal bond offerings.

Global fixed income securities and products in general, including structured debt products, mezzanine debt products, and distressed debt products, are another type of alternative investment. Many large financial services firms in the United States have a department or group that deals with creating such structured financial products and marketing them to clients, institutions and high-net-worth individuals.

In addition to all of these other alternative investments, both professional investors and retail investors also invest a notable amount into more speculative assets such as art, stamps, coins, and wine. However, given the difficulty in quantifying the extent of such investment, the private market nature of trading in such assets, and the difficulty in drawing the line between investing to achieve superior returns rather than simply collecting “treasures” as a hobby, these alternative investments are not the focus of this section. Moreover, it is abundantly clear that listed and unlisted real assets, currency, and debt products make up the vast majority of investment in alternatives.

FINAL WORD ON ALTERNATIVES

The decades leading to the turn of the twenty-first century were instrumental in the evolution of the global capital markets, with many alternative investments—private equity, venture capital, REITs, commodities, and infrastructure—entering the arena. In some respects, the growth and proliferation of alternatives occurred because of the democratization of investment. The increases in wealth for middle-class people and the resultant institutional framework that grew to serve them (namely, pension funds, university endowments, and other forms of educational, charitable, and retirement savings) created a demand for management services for these pools of capital. As explored in the next chapter, the compensation earned for such management was far from egalitarian, as some management activities take a significant share of the economics. The next section turns to investment vehicles that are even more obvious manifestations of the trend of democratization.

INDEX FUNDS AND EXCHANGE-TRADED FUNDS

We now consider radically different types of investment vehicles: the index fund and the ETF. Rather than being actively managed, with an investment professional making security selections through time, index funds and ETFs are passive and track a set of securities based on rules, such as sectors and market capitalization (the notable exception to this are the new active ETFs introduced after 2008, to be discussed later). This strategy allows the funds to charge fees much lower than those for actively managed funds. In recent years, ETFs and index funds have offered a major challenge to traditional mutual funds and to alternative investments as well and have a significant market presence. As of the end of 2012, there was a total of $1.3 trillion in index mutual funds and another $1.3 trillion in ETFs.54 This section looks at both vehicles in greater depth and places them in the greater context of the investment management industry as a whole.

Index Funds

Until the 1970s, personal purchases of baskets of individual securities or separate investment in mutual funds were the primary methods of investing in the broader equity markets. All that started to change on August 31, 1976, when Vanguard and its founder, Jack Bogle, introduced the First Index Investment Trust. The central premise was that simply buying and holding the broad stock market (in their case, the S&P 500) could provide better results than trying to beat it by picking stocks. At the time, the idea was quite controversial and was derided by the general investing establishment for striving to be no more than simply “average.”55 The fund was slow to catch on, raising only $11 million in the early 1970s—far short of the $150 million Vanguard thought it needed to cover the transaction costs associated with owning five hundred stocks in a single fund. Later in the decade, however, it began to see meaningful asset growth. In March 1980, Vanguard changed the name of the First Index Investment Trust to the Vanguard Index Trust, and the index fund growth trend was on.56

Vanguard was not the only player. In 1984, Wells Fargo launched the second index mutual fund, the Stagecoach Corporate Stock Fund. The fund had limited success—which, according to Bogle, was due to the fund’s high fees. The very purpose of passive management through index funds, he contended, was to allow the investor to have inexpensive exposure to an asset class and to forego the high fees associated with active management. And indeed, other early index funds with exceptionally high fees did not enjoy sustained success. Colonial Index Trust, for instance, generally involved a sales load of 4.75 percent and a running expense ratio of 1.5 percent. This fund lasted only 7 years, closing in 1993.57

It was not until the early 1990s that Vanguard started to see any meaningful competition. Vanguard had eleven different index funds by the end of 1992. That same year, thirty-five new index funds were formed by competitors, bringing the total number of index mutual funds in the investment market to just under eighty. The universe of product offerings also expanded. In 1993, Vanguard and some of its competitors offered the first bond index funds. With these, investors could get exposure to a wider array of investments than just equities. The bull market of the 1990s spurred continued growth in the industry, and many of the US equity index funds dramatically outperformed actively managed accounts during this time. Over the period from 1994 to 1996, some 91 percent of managed funds underperformed their index fund counterparts within US equities—a victory for the vehicle that was once derided as a recipe for mediocrity.58

Today there exist nearly 300 distinct stock and bond index mutual funds in the United States and over 1,000 American passive ETFs, and the world of investment has come a very long way toward not only accepting index funds as a fixture of investing but also fully embracing the power of indexing as one component of a strategy to outperform the market in terms of risk-adjusted return.59 The first index funds were meant for passive investors who simply wanted a small piece of the larger pie of the equity markets. Modern index funds, however, cater not only to passive investors who are looking for a broadly diversified portfolio of securities but also to active investors who want to enhance their portfolio returns by investing in particular asset classes through indexing. For instance, there are index funds that specialize in timberland investment, leveraged index funds that attempt to double or triple the return of a common stock index such as the S&P 500 on a daily basis, and index funds that specialize in commodities. With the widespread proliferation of index funds through all potential asset classes and market segments, and as the industry becomes more and more aggressive in marketing in order to remain competitive, investors must apply ever greater standards of scrutiny to their investments.

Exchange-Traded Funds

Closely related to index funds, ETFs first became available to investors in 1993. At the fundamental level, an ETF is a publicly traded investment company that can be bought and sold through brokerage accounts. These funds have a sponsor (often a large financial institution or bank) responsible for ensuring the ETF tracks the appropriate index. This is done either by full tracking—having exposure to all of the securities in the relevant index—or by representative sampling, where a subset of all of the names is owned in a manner that closely, but imperfectly, tracks the index. The benefit of the latter approach is lower transaction costs, but it comes at the expense of the possibility of additional tracking error.60

The differences between ETFs and index funds are subtle. First, ETFs can be bought and sold throughout the trading day, whereas index funds are purchased or redeemed once per day. Second, index funds are intended to trade at the net asset value of the portfolio’s underlying holdings, whereas ETFs can actually trade at a discount or premium to net asset value. Many ETFs do have mechanisms to prevent very large deviations in price from net asset value, but there is no structural reason that they have to trade at net asset value (as is the case for index funds). Index funds also reinvest dividends immediately whereas ETFs capture cash for distribution at a regular interval (often quarterly). There tend to be some tax advantages for ETFs over index funds because of how the shares trade and are redeemed, but the need to pay the broker and the bid-ask spread tends to result in higher transaction costs for ETFs. Although the differences between the two vehicles are nuanced, they are significant enough that when ETFs were first introduced, they had to receive exemptive relief from the SEC because the structure itself would not pass the provisions of the Investment Company Act of 1940.

The allowable mandates of ETFs broadened after 2008. Before 2008, ETFs were oriented around rules-based passive index tracking, but in 2008 actively managed ETFs emerged. Here, the role of the sponsor is a bit different. Instead of being charged with just tracking an index, the sponsor is responsible for active security selection. This process is complicated by a requirement that ETF managers provide a daily update of the securities the fund owns. As such, if an ETF is attempting to build a sizable position in a particular company, it runs the risk of other market participants front-running it. Given how new this vehicle is, the jury is still out on what influence the introduction of actively managed ETFs will have on the industry.61

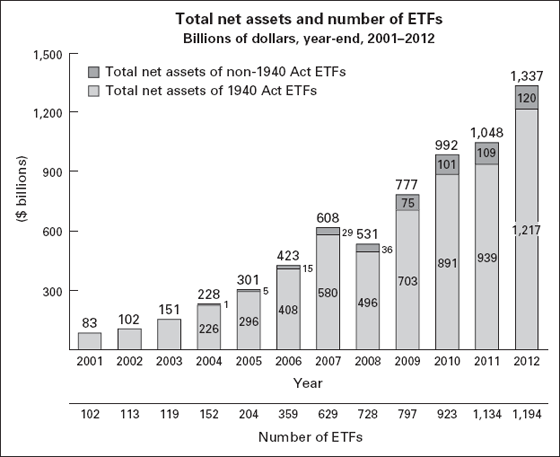

Exchange-traded funds, as an asset class, immediately caught on. Even with the collapse of the technology bubble and the dramatic fall in equity indices around the globe, assets in ETFs remained steady, and this growth accelerated tremendously at the turn of the millennium (see figure 8.2).

Figure 8.2 Total Net Assets and Number of Exchange-Traded Funds

Source: “2013 Investment Company Fact Book: A Review of Trends and Activities in the U.S. Investment Company Industry,” Investment Company Institute, accessed 2014, http://www.ici.org/pdf/2013_factbook.pdf, 47.

Among the ETFs created during this decade were commodity ETFs. The first commodity ETFs were introduced in 2004, and they grew from $1 billion that year to nearly $120 billion by the end of 2012 on the back of both strong precious metals demand and performance.62

Index funds and ETFs have substantially changed the world of investment management. Their rise and near ubiquity across all asset classes are testaments to the diversification and liquidity benefits provided by these investment vehicles. From being called a recipe for mediocrity to being fully embraced by both retail and institutional investors, index funds and ETFs have both become major challengers to traditional mutual funds. These investment vehicles have primarily targeted passive investors, but the explosion in ETFs has been accompanied by an increase in the complexity and intricacies of ETF design, which has begun to appeal to active investment managers as well. In many respects, the index fund and ETF embody democratization, permitting even small investors to participate with ease in a source of diversified investment gain. The individual investor can put his or her money to work with this wide menu of options bearing relatively low fees.

The future of the index fund and the ETF will undoubtedly be marked by more product innovation to allow investors access to more esoteric and less traveled corners of the market. This development is already underway with distressed debt and merger arbitrage, for example. The rivalry between passive and active vehicles will continue as investors become ever more thoughtful about how to benchmark active return using alpha analyses.

CONCLUSION

The future of the alternatives asset class is an open question. There are two crucial factors that will affect the trajectory of alternatives. The first is regulatory. Governments and securities regulators will undoubtedly pay closer attention and give greater scrutiny to alternative asset classes in order to protect investors and consumers of such products, particularly in the wake of recent examples of fraud and other forms of malfeasance. However, if history is any indicator, it will take time for appropriate regulation that finds the balance between allowing for the benefits of a market to emerge without unfairly shutting down entire market segments. Experts who were surveyed regarding the challenges facing the alternative investment industry over the next three years cited transparency, regulation, investment performance, and operational risks as four of the major obstacles to growth.63

The second factor is performance related. There will be increased pressure on alternative managers to identify an appropriate benchmark and outperform it, net of fees, as institutional investors become increasingly focused on whether alternatives are genuinely providing greater risk-adjusted returns than investable indices.

Indeed, all active management, conventional and alternative, is being challenged by index funds and ETFs. The persistent claim of lower cost and competitive performance is creating a higher barrier for active and innovative managers to clear, not only with the investing public but with institutions and high-net-worth individuals as well.

Whatever the case, it is clear that the next few decades will bring a great deal of change: the reaction of the financial industry to the institutionalization of private equity, venture capital, and other alternative investments will carry significant implications as novelty gives way to widespread familiarity and greater liquidity.