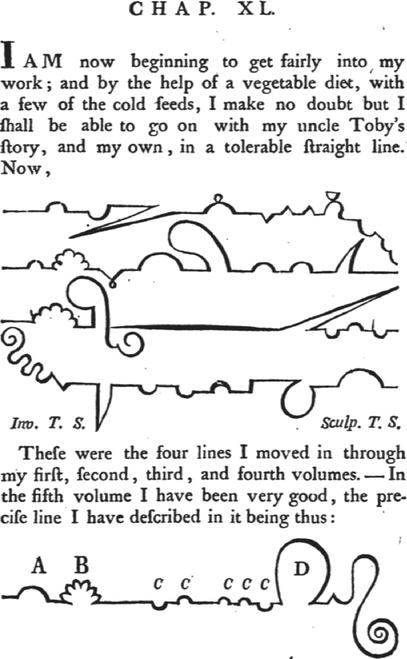

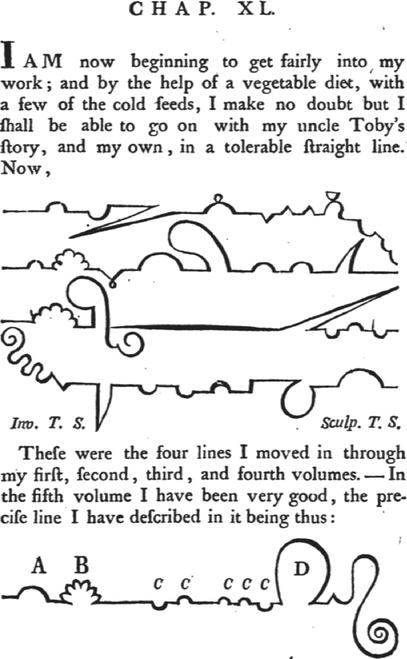

FIG. 5.1: The shapes of Tristram’s chapters, from Vol. VI, Ch. 40

On the Structure of Hegel's Phänomenologie des Geistes in the Light of Tristram Shandy

Tommaso Pierini

The connection between Hegel’s Phänomenologie des Geistes and literature is often drawn, particularly with regard to Goethe’s Faust and the Bildungsroman. Today, one speaks in general of the Phänomenologie as a great narrative at a time in which such narratives were supposedly no longer possible. Beyond this critical standpoint, objections to the Phänomenologie have been formulated with respect to the unity of the work, expressing doubts about its so-called metaphysical structure. Recently, various alternative concepts challenging these readings have been presented, including the general suggestion of Klaus Vieweg that we see the magnum opus of Hegel’s time in Jena in the context of the humoristic novel in the tradition of Sterne.1 In this essay, I will consider more closely whether this suggestion can be applied to the method and system of the Phänomenologie and whether it produces a significant contribution to solving the problem of unity in this work. If this is the case, then Hegel’s appreciation of Sterne has a philosophical significance that extends beyond aesthetics.2

Philological findings seem to speak against the unity of the work. Above all, we are concerned here with Haering’s thesis, which was improved by Pöggeler: that the Phänomenologie consists of two, separate parts, while the decisive break is to be found between the chapter on reason and the chapter on spirit.3 As a result, a problematic relationship originated between the ‘stringency of presentation’4 (Pöggeler) on the one hand, and the historicity of the shapes of consciousness on the other. Confronted with this dissonance, one of two solutions is possible: either Hegel is to be described as a thinker of historicity, without further reference to the method of presentation, or one insists on the method of presentation, regarding it as a rigid conceptual scheme for events. Both ways pertain to the relationship between methodical unity and time.

A third way of dealing with the problem of unity may be found in Rorty’s description of dialectic, which justifies his view of Hegel’s work as an ironic book. Rorty describes the method of the Phänomenologie explicitly as ‘literary skill’ and refers to ‘dialectic’ as ‘literary criticism’,5 the ability to play vocabularies off against one another, i.e. to replace older with newer vocabularies by means of redescriptions. Surpr isingly, the methodical fissure may be overcome by means of redescription; for this model would not require verification of the accuracy of various conceptual transitions within the same work. In addition, the term redescription would establish a reference to historicity, for philosophies would define ‘their achievements by their relationsh ip to their predecessors’.6 It is easy to see how Rorty’s view is hardly tenable in terms of philology: it seems to contradict Hegel’s insistence on scientific rigour. With the reduction of philosophy to literature and a deflationary theory of truth, the coherency gained has surely been bought at a high price. Yet Rorty’s insist ence on redescriptions touches upon an apt point (also in terms of philology): these must be included in thinking the conceptual transitions. According to Rorty, the thought process is characterised by what Hegel calls ‘dialectic movement’ (‘dialekt ische Bewegung’) in the introduction to the Phänomenologie: in a few words, the exper ience of the development of the new, ‘true’ object from the old.7 This includes a historical and a systematic element, and the latter should ensure that this move ment does not remain merely an arbitrary, subjective one. In Hegel’s own under standing, redescription implies not only a reorientation of thought, which can counter act the problem of structural changes, but also a genetic, systematically describ able experience — which must speak to the unity of the Phänomenologie des Geistes.

The genetic experience is related to Hegel’s famous concept of ‘determined negation’ (‘bestimmten Negation’), which was formulated with an anti-sceptical intention. Sceptical reflection results in nothing. This negation legitimises itself necessarily out of ‘what it resulted from’. Otherwise, a sceptical result would be a ‘trockenes Versichern’ [dessicated assurance], just as dogmatic as dogmatism itself. The way to genetic experience and the philosophical unity of the work should be won out of the non-descript feature that distinguishes a dogmatic nothing from a determined, established nothing. Here, we cannot concern ourselves with associating Hegel’s concepts of negation and experience — complex as they already are — and checking them for coherency. Instead, it is sufficient to focus on redescriptions to the extent that they can initiate a feasible path, experienceable as unified, which transcends mere subjectivity, contingency, and scepticism. Without being able to recons truct the concrete arguments of the individual chapters of the Phänomenologie, I shall attempt to proffer insights into its structure. As far as the problem of system and time is concerned, we would not be amiss in considering the ‘machinery’ of Tristram Shandy, as it is described in chapter 12 of the first volume. Sterne’s work offers a description of the ‘I’ that could be fruitful for an understanding of the Phänomenologie.

Parallels emerge even at first glance. Sterne’s book is supposed to, as the title announces, depict the life of Tristram Shandy. Yet his birth occurs only after the first several hundred pages. At the end of the fourth of nine volumes, Tristram, the protagonist, announces: now begins the story of my life and opinions.8 In Hegel’s Phänomenologie, the spirit, the eponymous protagonist, also makes its entrance only after several hundred pages, at the beginning of the sixth of eight chapters altogether. Earlier, as in Tristram Shandy, the story of the protagonist’s birth is told.

With regards to dramatic poetry, Tristram Shandy can be seen as a devastating parody of the so-called Aristotelian (or French) unity of place and time. This dramatic unity is mentioned at various points in the book. Particularly relevant in this case is the unity of time. The joke of the postponed preface in Tristram Shandy, which can only be written because the characters have fallen asleep and thus caused a break in the narrative time, is completely understandable when read in terms of the unity of time. Without this break, Tristram would not have been able to stop narrating. Furthermore, this unity of time is pursued to the point of absurdity, until Tristram notices that he will not be able to finish the book. The time that is technically necessary to process events and to write a narrative, as well as the narrated time, run differently than in life. The time required by the medium and lifetime do not coincide. Here, fractures occur. The fractures imply that time does not run in a straight line. Rather, in Tristram Shandy, past, present, and future exist in multiple relations to each other. And this has an effect on the structure of the book. Tristram explicitly thematizes the intricate plot. Now the question is whether it is accurate to claim that time in Hegel’s Phänomenologie is non-linear, as well.

FIG. 5.1: The shapes of Tristram’s chapters, from Vol. VI, Ch. 40

Time is a central concept in the Phänomenologie des Geistes. Even in the first chapter, ‘Die sinnliche Gewissheit’, fractures in time are thematized. In this chapter, it is established that our perception of objects is already decisively influenced by the convergence of three forms of time: the past, present, and future. Here already, all statements about ‘now’ are to be thought of in terms of the other forms of time. Perception is explicitly thematized as a kind of history (‘Geschichte’). According to Hegel, time is to be understood as a form of negation, as negativity. The course of the work, as well, just as in the course of the novel’s plot, is clearly non-linear. The unity of the work, indeed, is questioned. The history of the ancient world is told four times, universal history is narrated twice, i.e. both as world history and the history of religion — with different starting and endpoints! In addition, the individual chapters have varying lengths, similar to the chapters of Tristram Shandy, ranging from ten to one-hundred fifty pages. If we consider these simple observations, we see that the Phänomenologie mocks a linear view of history, just as Tristram Shandy flouts the dramatic unity of time. Accordingly, it is to be expected that the Phänomenologie will feature a more fragile, but all the more mobile unity. Duncan Campbell has shown that the topic of time is central for the entire construction of Tristram Shandy, not only on the formal level of composition, but also on the level of the theory of time. At several points in Tristram Shandy there occurs a discussion of straight lines, in which it emerges that these are both desirable and impossible. By way of contrast with straight lines — and like in Hegel’s Phänomenologie — knots are significantly central.9 This is particularly the case with knots of time. These obey neither a purely subjective nor an objective order. Rather they require a multidimensional correlation of the modes of time (past, present, future), which cannot be linear. By invoking Heidegger and Derrida, Campbell shows how in Tristram Shandy time is understood in such a way that the present manifests no priority over past and future. In the multidimensional correlation of the modes of time there rather appears a kind of original temporality and historicity, which has no rigid substrate.10 As Campbell emphasises, the problem of multidimensional temporality affects not only the unity of the work and the theory of time, but also the identity of the person himself — Tristram Shandy. It is precisely the connection between history, time and the identity of the consciousness that can be justly asserted for Hegel’s Phänomenologie.

The problem of the fracturing of time and the related erratic course of the plot in Tristram Shandy have to do with the conception of the work. Its development is non-linear, and it progresses in loops and digressions. So for instance a character is redescribed, and then gradually defined more closely in that the narrative pursues constantly different, deviating directions. New, progressive aspects, which enrich the illustration, are added through redescriptions, changes, and variations. According to Sterne, it is characteristic for his own work that it be ‘digressive’ and ‘progressive’, ‘and at the same time’.11 ‘Two contrary motions are introduced into it, and reconciled, which were thought to be at variance with each other’.12 The free digression in various directions is conceptualized so that these movements back and forth gradually, step by step, drive the development of the work forward and ensure its unity. In his Ästhetik, Hegel writes with respect to Sterne in somewhat different terminology: ‘Zum wahren Humor [...] gehört [...] viel Tiefe und Reichtum des Geistes, um [...] aus seiner Zufälligkeit selbst, aus bloßen Einfällen das Substantielle hervorgehen zu lassen’ [To true humour belongs much depth and wealth of spirit, in order to allow the substantial to proceed from its contingency, from mere inventions].13 Perhaps Hegel is even referring here to Tristram Shandy.

This digressive-progressive process creates an indirect development, while at the same time it presents the course of the plot in slow motion. Redescriptions do not only replace the old ones, as Rorty seems to propose. Because they differ from the old descriptions, they also enrich them. As far as the ‘dialectic movement’ of the Phänomenologie is concerned, Sterne’s digressive-progressive process fits even better than Rorty’s understanding of it. For in the Phänomenologie as well, the new should not merely supplant the old. Rather, the new is to be understood as a development of what preceded it. A further indication is the already mentioned slow motion effect that results from the Sternean process. This effect may also be noticed in Hegel’s Phänomenologie. Thus Hegel, undoubtedly a fan of postponed punchlines, writes in the fourth chapter, after about fifty pages: we have ‘now entered into the native realm of truth’ (‘einheimische[s] Reich der Wahrheit’).14 This truth is reached in full some four-hundred thick pages later, once the reader has pursued a succession of one-sided byways.

However, if we are to claim that the two works have an inner kinship, one critical difference must be discussed. If, according to Hegel, the humorous novel leaves a good deal of room for subjective invention, the Phänomenologie forbids that we apply ‘unsere Einfälle und Gedanken bei der Untersuchung’ [our ideas and thoughts during the investigation]. Hegel proceeds: ‘Dadurch, dass wir diese weglassen, erreichen wir es, die Sache, wie sie an und für sich selbst ist, zu betrachten’ [By leaving these aside, we succeed in regarding what is at stake as it is in and for itself ].15 This speaks to the heart of the comparison. If it is not possible to bridge this difference, then the similarities between the two works are only superficial.

The different approach to subjective humour and witty invention surely relates to the distinguishing features of literature and philosophy. We could at this point make the argument that the difference just noted may be traced back to the respective genres of the texts, and thus claim: if imagination is central for literature, philosophy is more concerned with substantive argumentation; whereas the latter deals with concepts, the former deals with description. Without doubt, Hegel also makes these distinctions. However, his differentiation would not bring us much further in this case. Besides the fact that the difference between philosophy and literature is not easy to define, we are not interested here in establishing distinctions, but rather in enquiring whether it is possible within these differences to find common ground regarding the approach to invention.

But what does it mean if we do not apply our ideas and thoughts, but rather leave them aside? Can it mean that all thoughts should be left aside? Obviously not. Here, an invention can mean a thought that differs from the preceding thoughts or changes them. In the sense of an alternative representation or redescription, the concept of Einfall is close to scepticism. The German word ‘Einfall’ combines diverse aspects, which are very difficult to translate with a single term. ‘Einfall’ means a thought, which occurs to one suddenly and immediately, an intuition, an idea: it can be extremely important, as with a genial thought, a (supposed) divine inspiration, but it can also be a joke or a gag. The affinity of ‘Einfall’ with wit and humour is clearly apparent. With regard to Hegel and scepticism it may be said that ‘Einfall’ can mean a thought, but also an invention or a subjective idea, which appears differently, and yet is immediate, without a previous foundation. It is here that the connection with scepticism is to be found.

The sceptical principle can also be understood in terms of one thought being contrasted with another, comparable thought. In connection with scepticism, it can also be argued that dogmatic precepts were also once someone’s subjective ideas, which can therefore be equated with other ideas. As is well known, the Phänomenologie des Geistes itself claims to be the ‘Weg des Zweifels’ [path of doubt], or the ‘sich vollbringende Skeptizismus’ [self-consummating scepticism].16 It intern alizes scepticism and methodically constructs steps forward, progression through variations. It portrays a path of ‘experience’ (‘Erfahrung’), which shows the consciousness its particular variations.

In this manner, the play of alternative descriptions, which generate progress, pertains to the consciousness itself. The consciousness problematizes its approach, tries out variations, and draws up its own criterion for unity, only to call it into question again. In view of this, it is not surprising that the method of the Phänomenologie is described as follows: ‘Das Bewusstsein gibt seinen Maßstab an ihm selbst, und die Untersuchung wird dadurch eine Vergleichung seiner mit sich selbst sein [...]’ [Consciousness in itself provides its own standard, and the investigation will thereby be a comparison of itself with itself].17 According to Hegel, this is precisely what characterises humour as opposed to merely negative scepticism: to let something substantial come out of variations. As long as it carries in itself the germ of humorous refraction, the consciousness furnishes the first methodical leads for epistemo logical assessment.

The comparison between Tristram Shandy and the Phänomenologie reveals that we are confronted with two different forms of handling variations in the consciousness. In the humorous novel, variations relate to each individual subjectivity, or rather contingent events; in the Phänomenologie, a universal knowledge is generated from the subject. These are two (thoroughly compatible) versions in which consciousness presents itself — and by no means unusual ones. We should keep in mind that the ‘I’ has been understood and applied in relation both to each separate individuality and a universal dimension since Descartes. Thus the problem with ‘ideas’ is that they should not be merely ‘ours’ alone. Hegel, who was well schooled in the problems of subjectivity as they come up in, for example, Fichte’s Wissenschaftslehre, would not have had any difficulties discerning these varieties of the uses of the ‘I’; they are indeed linked with his theory of the ‘I’ in Wissenschaft der Logik.

Returning to the Phänomenologie, we shall briefly consider the concept of consciousness. In the introduction, the consciousness is characterised by five points: first, Hegel defines it as object-related. Consciousness is the consciousness of the object. Second, it has knowledge of this; which produces (third), criteria to determine how its knowledge accords with or does not accord with the object. Fourth, the consciousness undergoes a process in which variations sceptically call into question its own present criterion. Fifth and last, it produces redescriptions that accommodate the variations that have occurred and maintain the unity of the consciousness, and of knowledge, as well as of the work. These variations emerge as long as the knowledge of the consciousness does not correspond with truth. Through all of these variations, the concept of consciousness should hold everything together. The consciousness is characterised epistemologically by the first three points; the fourth and fifth points address the relationship between variation and development, digression and progression — as Hegel sees it at work in the humorous novel. The substantial is to develop out of contingency, knowledge out of scepticism. Even if the chapters are of unequal lengths, fractures in time occur, eras are treated multiple times in different ways, changes in the self-perception of the consciousness occur — all this is unproblematic as long as the consciousness can maintain unity through digressive-progressive redescriptions. That this is the case in the Phänomenologie has less to do with the external genesis of the book than the immanent interpretation of the text, how it represents itself step by step. As far as the Phänomenologie is concerned, a glance at Sterne’s novel teaches the philosopher not to resort too hastily to thoughts of unity, simply because he does not want to consider other, more intricate, digressive paths. Here, the concept of consciousness plays an important systematic role.

The following objections might be made to such a reading: first, we are used to speaking of a conceptual division of the Phänomenologie into two parts. This seems like merely dodging the problem, since more liberties have been taken regarding the shape of the text than is justified with a philosophical work. As a principle, if we allow for too much conceptual reconfiguration, the system is lost in the lack of limits. However, the division into two parts is not the only way that Hegel describes the structure of the Phänomenologie. As is well known, he also speaks in terms of a Christian metaphor of ‘stations’ (‘Stationen’) that run through the consciousness — of which there surely must be more than two.18 In addition, Hegel specifies another, more concrete illustration of the system. According to Hegel, the shape of religion has four moments with which it represents the whole. If we take into account the section on absolute knowledge (‘VIII. Das absolute Wissen’), altogether six conceptual shifts take place in the Phänomenologie. The problem of the division of the work into two parts is thus at least relativized. In fact, a method of investigation is necessary that at the beginning allows for the most different conceptions. Scepticism is most fitting for this task. It is then important simply that the system should thereafter define itself with increasing precision. Like a character in a humoristic novel, the concept of consciousness and its systematic description determine themselves through all the variations. Second, thinking in terms of the metaphor of Good Friday just mentioned, it might be objected that the theses presented here are too light-hearted and optimistic. According to this view, it would be more appropriate to attend to the central similarity manifested in the Christian life of suffering, the humorous novel and the idea of a self-perfecting scepticism (in contrast to dogmatic scepticism). This similarity would be the thought that negativity, which appears in various forms as contingency, suffering, temporality, and negation, can be transcended by stepping through it. If we wish to develop a more accurate account of the system of the Phänomenologie, we must orient ourselves from the idea that negativity and systematic form are to be thought of as a unity.

The consciousness, which defines itself through variations, does so in terms of that negativity and of a totality which contains it. Both are to be held together. The elements which we must take into account here are negativity, the consciousness, its unity, and the structural dynamic of the experience that it undergoes. As already mentioned, periods of experience do not occur in linear time; they need to be arranged in a different way. The negative, which the shapes of consciousness experience, manifests itself as experience of the objective and real in any given case. The consciousness experiences the negative variations in reality’s process of becoming as the passing of time. Sections of time are experienced, which, in their dynamic, follow strictly in succession. With respect to each other, however, they do not stand in a relation of temporal sequence. In addition, we must add the following: if time represents negativity’s form of reality and the consciousness constructs its unity through negativity by internalising it, then consciousness will also internalise time. To internalise time, however, is to overcome it.

Various systematic threads converge in the concept of time: (i) the temporal condi tion of the formations of the consciousness in their entirety; (ii) the non-temporal arrangement of the same; and (iii) its inner, structural unity. Hegel approaches these complex connections in the preliminary remarks to the chapter on religion. There, we find Hegel’s indications as to how the work is concretely constructed. The dynamic of the work is related to the thesis that ‘Der ganze Geist nur ist in der Zeit’ [only the whole spirit is in time].19

The individual formations of the consciousness create ‘particular wholes’ (‘besondern Ganzen’) that proceed in time. These are the sections ‘Bewusstsein, Selbst bewusstsein, Vernunft und Geist’ [consciousness, self-consciousness, reason, and spirit].20 These are also differentiated further into partial shapes, but we shall not deal with these sub-divisions here. (i) In each section, the shape of the consciousness experiences the nullity of its truth claim, which is embedded in a temporal occurrence. This nullity represents the nullity of the shapes of the consciousness itself to the extent that the latter are determined by their claim to knowledge. (ii) A negative experience happens in each one; its course begins with the experiences of the preceding fragments. In this way, a progression is created which is abstract, i.e. non-temporal. It is only an epistemic progression in the consciousness. The reason is that the experiences that are had in these ‘particular wholes’ may be characterised as partial experiences. ‘Consciousness, self-consciousness, reason, and spirit’ create the epistemic prerequisite for the concept of a structural totality, which according to Hegel is only reached in the section on religion. They are, however, only moments on the way there. Religion contains them and holds them together.

The construction of the work is not linear, but rather ‘broken’,21 because the experiences in the consciousness, reason, and spirit come to a negative end, for their structure is not complete. Their negativity refers to the complete structure that incorporates this formation of the consciousness as moments, so that at the same time ‘knots’ (‘Knoten’) form at the ends of these moments in their unresolved contradictions. These ‘knots’ hold together structural totality.22 ‘Consciousness, self-consciousness, reason, and spirit’ represent in their respective ways one-sided histories, which display an epistemic progression that is not temporally successive. In this respect, it is not problematic that the same topics come up in various chapters. This occurs with a changing focus, and the temporal succession of the events among chapters may be ignored.

(iii) With consciousness, self-consciousness, reason, and spirit as the respective particular wholes, two characteristics coincide. They are indeed totalities, but at the same time temporally finite. Therefore, they must be seen as finite totalities. Even religion as the actual whole runs an historical path of experience, for according to Hegel, religion has a side that manifests an insufficient form. It is through certainty that it must attain knowledge of its object. This development is a temporal one. The outcome is a complex relation between time and the totality of a shape of the consciousness. On the one hand, the temporality of the shape of the consciousness depends on its totality. On the other hand, temporal succession is determined by the fact that the totality has not yet been reached — whether because totality is in itself fragile, as with the moments of consciousness, self-consciousness, reason, and spirit, or because knowledge is not sufficient for totality, as in the chapter on religion. In terms of structure, time essentially follows totality; according to appearance, totality follows time.

If, however, totality could not at all be recovered temporally, we could not speak of the significant precedence of the whole; that precedence could only be postulated. If totality were through and through temporal, then it would be a matter of the precedence of time. Even then, the thesis of the precedence of the whole over time would not be substantiated. This substantiation is, however, necessary if we, like Hegel, consider successive, temporal courses in terms of a whole. The Hegelian solution to this difficulty emphasizes the appearance-character of time. Totality appears in time as long as it has not been grasped, has not been consummated.23 Negativity, the characteristics of which were briefly described already, connects the form of the whole and time. Time is seen as the actual form of the negative in that the consciousness and the spirit have not yet internalized it. If this has happened, totality is no longer in time. We are concerned with the same negativity: in one form already internalized, in another form not yet grasped and therefore expressed as time.

Here, the epistemic ascertainment and the consummation of totality are decisive. We might first say the following: it is possible to think in terms of consummation for two reasons. A whole can be seen as completed, because it has already found its end. This is surely the case of consciousness, self-consciousness, reason, and spirit, which are to be regarded as finite totalities. Time remains, even after these forms of consciousness have been completed. Second, we might speak of consummation even more appropriately when something has reached its goal. If totality is in this way rounded off, negativity is internalised and time effaced.24 The ascertainment of totality is necessary for this effacement to occur. This is an epistemic activity.

The Phänomenologie features five sections with regards to content. However, it attains its purpose and systematic shape in the end in the section ‘Absolute Knowledge’, in which experiences are gathered. In this way, the arrangement of shapes takes on a ‘4+1+1’ form. Hegel calls absolute knowledge the ‘letzte Gestalt des Geistes’ [last shape of the spirit].25 Thus there are three shapes of the spirit and three ‘nur des Bewusstseins’ [merely of consciousness].26 The above-mentioned division into two parts follows from the ’3+3’ shapes. We might also offer further provisional arrangements of the text, for which there would be sufficient basis in the text. We could, for example, exclude absolute knowledge with the justification that only there has a shape been reached which does not lead to anything else (5+1). Or, alternatively, we could isolate the first chapter (1+5), for the ‘Reich der Wahrheit’ [realm of truth] begins with the self-consciousness.27 Or, we could detach the first and the last chapters (1+4+1, or 1+2+2+1) in the service of regaining the symmetry of the division into two parts. In a Sternean manner, one could continue to play this game. However, decisive is how the shapes relate to each other conceptually.

Along general lines, consciousness, self-consciousness, reason, and spirit constitute four finite histories on the path of experience towards the actual totality of these four moments, which are represented in the chapter on religion. Religion unifies the four moments into a whole, which arrives at a significant clarification of its content only through the historical becoming of particular religions; in the terms implied, religion is thus to be characterised as non-temporal, eternal. Religion indeed lends itself to being the place in which the eternal can be thematized. Nevertheless, religions occur in time, i.e. the history of religion reveals a dynamic according to which there is a side of the object that remains unrecognised, removed from knowledge. Without going into too much detail, however, we can say that this unrecognised side is concerned with the ‘real world’. This term stands for social history from the spirit chapter and for the history of science from Vernunft. Although religion contains an historical development as its moment, it at the same time neglects to perceive the worldly and epistemic aspect of this history.

The outcome is five histories that systematically follow from one another — although chronologically they are both overlapping and separate. All five represent the temporal appearances of the whole, even if it is only religion that itself actually thematizes the whole. In them, experiences of negativity are gained, even if the experience of transcending negativity and temporality is actually gained in religion. Nevertheless, this arrangement is not to be realized in its concrete form with the means of the chapter on religion. The cognitive ascertainment devolves into a sixth step, the section on ’absolute knowledge’. Cognition, which retains epistemic progression, the common thread of histories that drift away from one another, is also the activity that rounds off the work as a whole and the negativity that overcomes temporality.

Because the cognition that forms the totality runs through the path to the construction of the whole, it is itself temporal; it has a history. The history of knowledge represents that of the spirit, which has not yet cognized itself. It is the history of the consciousness, which has gained experience about itself. It is the whole history, the ‘actual history’ (‘wirkliche Geschichte’).28

We are concerned with a temporal series of events which appear ‘in der Form der Zufälligkeit’ [in the form of contingency] and as such are preserved as history.29 Against the background of this contingency, actual history reveals itself not merely in a linear manner. It contains particular histories, as well, that drift away from the main path, and it allows for different, disparate perspectives on events as they have been recorded in history. The Phänomenologie des Geistes has the task of indicating the red thread of actual history and of showing how the principal direction of the history of the spirit, which experiences and cognizes itself, is related to its digressions. It develops the epistemic guidelines for interpreting history in that the ‘actual history’ of the cognisant spirit is preserved. Thus the Phänomenologie may be characterised as the ‘Wissenschaft des erscheinenden Wissens’ [science of phenomenal knowledge].30 The common thread ensues in absolute knowledge from the sum of the experiences, the completion of the history of religion with that of the Enlightenment, social history, and the history of science from the reason and spirit chapters.31 This common thread and history form the ‘grasped history’ (‘begriffene Geschichte’) in which continuity and discontinuity, progression and digression are brought together.32

In one respect, the epistemic red thread, the path of the science of the appearing spirit, cannot be historical, in that the path of the Phänomenologie is not historical, but rather epistemic. The opposite side of this path is actual history. There is no further history that might be considered the essence of actual history. Nevertheless, there is still a path, and at the end of the Phänomenologie, we can also ask ourselves who travelled along that path and what kind of experience was gained that can assume this epistemic, concluding function.

Just as the shapes are those of the consciousness or of the spirit, we are concerned here with an experience that pertains to the consciousness or spirit. Because for Hegel all shapes are to be counted to the consciousness, a consciousness has taken this path. Nevertheless the relationship between consciousness and spirit in the Phänomenologie is thoroughly complex. Both concepts characterise further shapes in the sense described. There are shapes ‘merely of consciousness’,33 which are at the same time shapes of the spirit. The shapes that emerge first (consciousness, self-consciousness, reason) relate to each other as follows: the consciousness determines and begins the first part of the Phänomenologie; it becomes, however, the moment of self-consciousness, which at the same time bears negatively against it; at least until its unity is thematized in reason. The discussion of reason is related to the Kantian use of the word. In Kant, reason relates to the areas of both theoretical and practical philosophy. It is the capacity of principles and systematics of these areas. In the Phänomenologie the treatment of theoretical objects is related to the consciousness, while praxis is accorded to the self-consciousness. Its unity and systematics are situated as the primary concern of reason. In the corresponding chapter of the Phänomenologie, which critiques reason, there is a search for the unity of the consciousness and self-consciousness in insufficient, one-sided forms. The actual unity exists in the spirit, an objective world, which at the same time has a self in the social world and social history. Consciousness, self-consciousness, and reason are contained as moments within it.

If we compare now the course of the consciousness with that of the spirit, it is possible to say something similar about the latter: the spirit determines and begins this part; but it becomes a moment of the history of religion, which bears negatively against the worldly, the temporal of the spirit. Ultimately, unity is grasped in absolute knowledge, in actual history. If the chapter on the spirit presents the consciousness of the spirit and the chapter on religion presents the self-consciousness, then absolute knowledge reproduces its reason, the unity of the consciousness and self-consciousness of the spirit. The path from reason (merely of the consciousness) to reason (of the spirit) portrays four steps towards the understanding of what it is that comprises the unity of consciousness and self-consciousness.

The experience of the consciousness concerns its own unity with itself, as well as the entire investigation described as a ‘Vergleichung seiner mit sich selbst’ [comparison of itself with itself].34 The experience that the consciousness gains throughout the Phänomenologie has the following characteristics: it is a singular experience in knowledge; it combines several historical experiences; it has a temporal counterside, yet it is still not temporal. As historical consciousness, it cannot stride through these particular experiences as an individual, but it must also do so as a universal consciousness. It can only sum up experiences that pertain to further stretches of human history from the standpoint of the spirit, i.e. the standpoint of the consciousness that perceives itself as part of the historical world. The whole experience consists in the unity of the consciousness with itself. This unity reveals itself to be a principal problem of the system of reason. When the consciousness finds unity with itself, the unity can also indicate the system of appearing knowledge. The stations of the Phänomenologie des Geistes are thus concerned with an epistemic, nontemporal experience, which the consciousness gathers about itself as reason. This experience is not temporal because reason is in the specified sense not temporal. The consciousness experiences itself throughout the Phänomenologie as reason and in this way arrives at knowledge about itself as reason.

Tristram Shandy and the humorous novel around 1800 may be considered literary points of reference for Hegel’s Phänomenologie des Geistes, for they express a view on the consciousness that in a certain sense goes beyond scepticism. The so-called ‘dialectic movement’ requires redescriptions that bring the old together with the new in a unified image. Yet this does not occur smoothly, in a linear manner. A consideration of the concept of time reveals that redescriptions exhibit fractures. Time renders this fragility in variations, in the thinking of contingency, in scepticism, in the nullity of the finite, in historicity. To re-describe coherently is to gain perspectives, which are capable of persisting through scepticism and contingency. Just as with humour in the midst of temporality, it is possible to filter out what is important, the consciousness that is threatened by its own scepticism in the midst of temporal contingency can allow for the substantial to emerge. As far as the Phänomenologie des Geistes is concerned, we have a concept of the consciousness, which can generate coherent descriptions in variations. In attempting to find a stable unity for itself, the consciousness will also produce, as reason, which has recognized and understood itself as such, a more stable structure for time — indeed for history.

Translated by Kathleen Singles

1. Klaus Vieweg, ‘Die Phänomenologie des Geistes als der Lebenslauf der Sophie’, Hegel-Jahrbuch (2002), 208–13.

2. In this essay, I will use two abbreviations: one for Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (TS), ed. by Melvyn New and Joan New (London: Penguin, 2003); the other for G. W. F. Hegel, Phänomenologie des Geistes (PhG), ed. by J. Hoffmeister (Hamburg: Felix Meiner, 1988). The long-standard English translation of Hegel’s work is Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. by A. V. Miller (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978). However, this is set to be replaced by Terry Pinkard’s forthcoming translation, currently available online in the form of a final draft in PDF at <http://terrypinkard.weebly.com/phenomenology-of-spirit-page.html> [accessed 2 November 2012]. In this chapter, the English translations of the Phänomenologie are therefore taken from Pinkard.

3. See Th. Haering, ‘Die Entstehungsgeschichte der Phänomenologie des Geistes’, Verhandlungen des dritten Hegelkongresses, ed. by B. Wigersma (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1934), pp. 118–38. ‘Im überlangen Vernunftkapitel zerbricht endgültig Hegels ursprünglicher Plan, der schon bei der Darstellung des Selbstbewusstseins nicht mehr in aller Strenge befolgt worden war’ [In the overly long chapter on reason, Hegel’s original plan is finally disrupted; already in the representation of the self-consciousness, it was no longer being followed in any strict sense]. Otto Pöggeler, Hegels Idee einer Phänomenologie des Geistes (Freiburg and Munich: Alber, 1993), p. 22.

4. ‘Bald lässt die Strenge der Darstellung nach; sie wird breiter, konkrete geschichtliche Gestalten wie Stoizismus und Skeptizismus tauchen auf’ [Soon, the stringency of presentation slackens; it becomes wider, and concrete, historical forms such as stoicism and scepticism emerge]. Pöggeler, Hegels Idee einer Phänomenologie des Geistes, pp. 216–17. However, in a newer essay, Vieweg has pointed out that each occurence of scepticism has thoroughly systematic meaning for the entire Phänomenologie. Klaus Vieweg, ‘Hegels lange Rochade — Die “Umkehrung des Bewusstseins selbst” ’, in ibid., Skepsis und Freiheit, (Munich: Fink, 2007), pp. 85–108.

5. Richard Rorty, Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), pp. 78–79.

6. Ibid.

7. PhG, p. 66.

8. TS, Vol. IV, Ch. 32, p. 302.

9. Cf. Duncan Campbell, The Beautiful Oblique: Conceptions of Temporality in Tristram Shandy (Oxford, Bern and Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2002), pp. 69–74. Tristram voices his objection to the attitude of ‘cutting the knot’ instead of untying it (TS, Vol. 4, Ch. 7, p. 250). In Hegel’s work there occurs a succession of knots and lines, the latter emerging when the knots are untied (for further discussion, see the section ‘Time and Temporality’, below). For that reason we definitely shouldn’t keep our hands off the knots, but get involved with them. This corresponds to Tristram’s attitude: ‘every hasty man can whip out his penknife and cut through them [the knots].—— ’Tis wrong. Believe me, Sirs, the most virtuous way, and which both reason and conscience dictate—is to take our teeth or our fingers to them.’ TS, Vol. III, Ch. 10, p. 151.

10. ‘Tristram Shandy is the entanglement of different sites of time, a labyrinthine knotting whose traverse zigzaggery complicates not only the narrative presentation of temporality, but also the identity of the text’s narrative subject, Tristram Shandy.’ Campbell, p. 109. See further Christoph Henke, ‘Tristrams Zeitprobleme: Verzögerungen, Anachronismen und subjektive Zeit in Laurence Sternes Tristram Shandy’, in Zeit und Roman: Zeiterfahrung im historischen Wandel und ästhetischer Paradigmenwechsel vom sechzehnten Jahrhundert bis zur Postmoderne, ed. by Martin Middeke (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2002), pp. 91–109; and Jens Martin Gurr, ‘Geschichte(n) erzählen’: Zeitstrukturen und narrative Sinnstiftung in Laurence Sternes Tristram Shandy zwischen Aufklärung und Metahistorie’, Das achtzehnte Jahrhundert, 30.2 (2006), 193–206.

11. TS, Vol. I, Ch. 22, p. 64.

12. TS, Vol. I, Ch. 22.

13. G. W. F. Hegel, Vorlesungen über die Ästhetik II (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1986), XIV, p. 231.

14. PhG, p. 120.

15. PhG, p. 65.

16. PhG, p. 61.

17. PhG, p. 64.

18. PhG, p. 60.

19. PhG, p. 446.

20. Ibid.

21. PhG, p. 448.

22. Ibid.

23. PhG, pp. 524–25.

24. PhG, p. 524.

25. PhG, p. 523.

26. PhG, p. 290.

27. PhG, p. 120.

28. PhG, p. 526.

29. PhG, p. 531.

30. PhG, p. 531.

31. PhG, pp. 517–23.

32. PhG, p. 531.

33. PhG, p. 290.

34. PhG, p. 61.