IT may be proper, before proceeding to the target, to offer a few remarks on sights, bullets, powder, etc. Respecting the sighting of a rifle, I find Cleveland’s remarks so completely explain the subject, that I can not do better than quote him. The telescope sight is only applicable to the heavy target rifle, and therefore useless to sportsmen. The “globe” and “peep” sights consist of a small metallic disk, pierced with a very minute aperture, and fixed upon the stock of the gun by a screw or slide, by which it may be raised or lowered, and a bead or globe upon the point of a slender steel wire on the barrel, just over the muzzle, protected by a cylinder of steel in which it is inclosed. The bead is sighted through the pin-hole of the back sight, and, being brought in line with the target, affords a very perfect means of directing the shot. But even this is too delicate an arrangement for field service, and is rarely used, except for target shooting, though commonly furnished with the equipments of a thoroughly furnished rifle, to be made use of when required.

The most common arrangement consists of a bead or “knife-edge,” of bright metal, fixed in the top of the barrel just over the muzzle, and called the “foresight,” and an “after-sight” or guide-sight, near the breech, which is constructed with a notch like the letter V, through which the fore-sight must be aligned with the target. If these sights are properly arranged, so as to be in the same vertical plane with the axis of the barrel, the line of sight drawn through them should coincide precisely with that of the flight of the bullet, except so far as the latter is affected by external influences. It is rare, however, that the sights are arranged with perfect accuracy as they come from the gun-maker’s shop; but the error may be detected by a few experiments, and rectified by moving the foresight a little to one side or the other, as it is commonly fixed upon a plate which is moveable in a slot cut across the barrel.

The after-sight being so arranged that it may be raised or lowered, the proper degree of elevation of the line of fire for any distance, within the range of the piece, may be given, and the line of sight still directed exactly at the target. In order, however, to render this power practically useful, it is necessary that the degrees of elevation for different distances be ascertained by actual trial, and marked upon the slide or screw of the sight, and also that the shooter should acquire the power of estimating distance by the eye, so that he may be able to tell by a glance at the object at which he wishes to shoot, the degree of elevation required. And the longer the range the more important it becomes to estimate exactly the distance; because, at the end of a long flight, the bullet is falling more rapidly, and describing a much shorter curve, than at the end of the shorter one, and consequently the probability is much greater either that it will fall short or overshoot its mark, than when it is moving more nearly in a horizontal direction. From this it will be understood that for fine shooting, “peep and globe” sights are necessary; but for ordinary sporting purposes, where “snap” shots are common, a sight must be used by which aim can be taken instantaneously. A very large number and variety of sights are in use in England and on the Continent, and a long chapter might be written upon them, but I do not purpose dilating at greater length upon this subject. The sights above noted are quite sufficient, if used to advantage, to enable the learner to attain to such a degree of excellence as will enable him to experiment for himself. In Captain Heaton’s “Notes on Rifle Shooting” will be found some very interesting particulars respecting sights and sighting. One point must not be omitted,—avoid all brightness of metal about the sights, or it will be found impossible to make good shooting from the glare caused by the sun shining on bright or polished metal. The fore-sight, if open, should be of a dead black, and let the back-sight at the V be smoked, or in some way blackened, to avoid the reflection. In using a muzzle-loader, great care must be taken in the preparation of the bullets, if good shooting is to be expected; the purest lead must be used and the greatest nicety observed in casting them. Use a large ladle, and do not make the lead too hot; the bullet-mould can not be too clean, in my judgment, though some writers advocate smoking it; and it is desirable that it should be heated before commencing, or otherwise lay aside a couple of the first cast; by this means the mould is in good order, and the bullets will drop readily from it. When a number have been cast, they should be passed through a steel gauge of the precise intended diameter. They should then be trimmed off, oiled, and put together and worked in a bag, after which they are to be “swedged,” and laid aside for use.

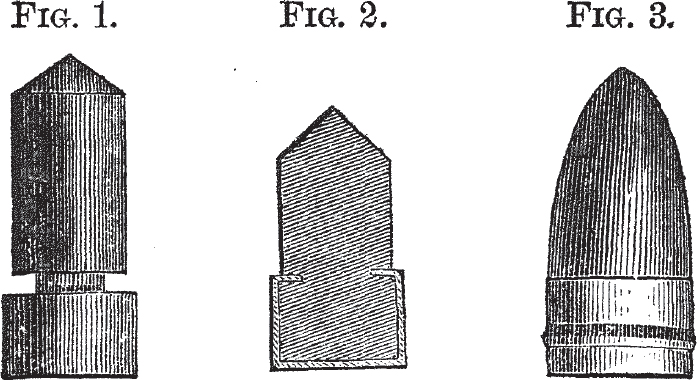

Among the many ingenious inventions connected with breech-loading fire-arms, I must not omit to mention PECK’S PATENT PATCHED BULLET, which is thus described by the inventor:

“No rifle-barrel can be made perfectly true in its inside caliber; and it is the universal practice among riflemen, where close shooting is required, to patch the bullet, in order to insure a smooth, even fit, and perfect lubrication between the bullet and bore of the rifle. The ease with which this is accomplished with the old muzzle-loader, and the want of any device for doing the same for the breech-loader, have caused the old rifle to retain its place among riflemen for sharp shooting. With the use of the invention herewith illustrated the breech-loader will, in addition to its other advantages, possess all the accuracy of the muzzle-loader. Fig. 1 represents the bullet cast as it comes from the mould and ready to receive the patch—which patch may be of cloth, parchment, paper, or other material. The patch is by means of a die brought over the end and the edges turned into the groove around the casting, where it is secured by pressing down upon it the the upper portion of the casting, leaving it as shown in fig. 2, which is then placed in another die which gives it any form required for muzzle or breechloader, as in fig. 3, which is designed for use in the metallic cartridge of the breech-loading rifle.”

Having no experience of the merits of this invention, I can not pass any opinion on it, though it appears as if it might be serviceable.

The next item, and a most important one it is, to be considered is the powder. Never use any but the very best; it is the poorest economy, and causes great vexation to use common powder. All writers and “crack shots” urge this point. Captain Lacy, in his work the “Modern Shooter,” says, “It is the very life-blood of shooting; for if indifferent, the very best guns are comparatively of but little use.” If good at first, and afterward kept perfectly dry, as it ought always to be, it will retain its virtues unimpaired for a considerable time; but if it once gets damp, and particularly if it remains so for any time, the grains have a tendency to dissolution or decomposition, which no after-drying can ever so fully recover as to restore the powder to its pristine strength. It ought to be kept wholly excluded from atmospheric influence, as the saltpetre, especially if not of the purest kind (and it is often impregnated with marine salt, which vastly increases its tendency to absorb moisture), readily imbibes damp; and powder will preserve its strength,—to say nothing of greater safety from accidental explosion,—better for two years in tin than for one in wood. It is unnecessary for us to inquire who invented gunpowder, whether it was known (as is claimed by some writers) to the Chinese as far back as two thousand years ago, whether it was used at the seige of Mecca in the year A. D. 690, is of very little consequence. It was not manufactured in England until 1346, and was necessarily of very rude make. It is composed of sulphur, saltpetre, and charcoal in the following proportions: twelve, seventy-four, fourteen; very little variation from these proportions being made by any nation. The very best powder that I know of is Curtis & Harvey’s No. 5 or 6; next to that the Roslin Mills. Some of the American powder is very good, particularly the “Orange,” manufactured by Smith & Rand, of New York, and which is unquestionably the best that I have met with of American manufacture. At the test of arms in Washington in 1866, cartridges made with this powder gave far superior results as to penetration, range, and cleanliness, than those made from any other American powder. Another proof of its superiority is the fact that at the State trial of arms, at Albany, May 18, 1867, it was one of the conditions that “the powder to be use is the Orange Rifle Powder, Fg.” It possesses all the necessary qualifications, such as uniformity in appearance of the grains, which are crisp and sharp to the touch, and not easily reduced to dust by pressure between the fingers, nor dusty in handling. I have full confidence in recommending this powder to gentlemen desirous of obtaining a good article of native production. It is claimed that powder that is very slow of combustion is best suited to the purpose of target firing; and Chapman recommends that made by the Boston Company, for Mr. Wesson, on account of its “mildness and moderate strength, because the English and some other noted powders are too good and strong for the target rifle.” A quality of powder is made in England and America, expressly for rifle-shooting, and known as “Rifle Powder,” so that no difficulty will be found in selecting the right kind. Fire a number of shots with different kinds, carefully noting the results, and that kind that gives the closest and most uniform shooting, is best suited to the gun.

I had purposed making some remarks on the adaptability of gun-cotton as a fulminate, but fear to do so, owing to the transition state the manufacture of it is in. Numerous experiments are being made to utilize it, and, doubtless, ere long we shall see some satisfactory solution of the problem. Billinghurst uses it with his small pistol, and some extraordinary shooting has been made with it. It is also proposed to enclose it in a waterproof casing of India-rubber.

Having now, I believe, laid down such principles and given such directions as will enable the young beginner, I trust, to understand the principles of rifle-shooting, and having chosen his arm, I propose now to offer him a few remarks how to go to work, to make a practical use of what he has already learned.