Consolidating your beehives makes the use of bear-resistant fencing more practical. A well-protected and maintained bee yard provides nearly complete security

Nonlethal approaches to predator control include secure fencing and housing, good husbandry and management, and disruptive and aversive stimuli.

The most successful and effective predator protection programs combine various techniques in a flexible plan suited to different times of year and grazing areas.

Choose the elements that best suit your predator threats, the changing predator pressures during the year, your location, your terrain, and your stock. Predators can become habituated to some techniques, necessitating moving or changing your methods.

Digging deeper into the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) predator data for cattle and sheep, we can learn a great deal about the current favored nonlethal control methods, where they are working, and what needs to be done. To date, sheep owners have developed and adopted most of the nonlethal control methods, and results are positive. More than half of sheep operations now use one or more nonlethal methods of predator control. The use of these methods has doubled since 2004, and both sheep and lamb predator loss is now less than in any study year in the past 20 years.

The specific strategies that have more than doubled in use include fencing, livestock guardian dogs (LGDs), donkeys, lamb shedding, active herding, night penning, fright tactics, bedding changes, and frequent checks. The use of guardian llamas has decreased. Owners of fewer than 25 sheep use fencing, LGDs, night penning, and lambing sheds in that order. Operations with more than 1,000 sheep, often on range or in large grazing areas, use LGDs, more frequent checking, culling older animals, changing bedding, and fencing, in that order.

Nonlethal predator control methods on cattle operations have been far less utilized, although that practice is also increasing. In 2000, only 5.4 percent of cattle raisers used at least one method; by 2010, 12.4 percent had adopted some techniques. The use of guardian animals, fencing, and carcass removal nearly tripled. The most commonly used strategies included guardian animals, frequent checking, fencing, and culling.

Work remains to be done on increased and improved use of nonlethal techniques. To that goal, specialists from the USDA National Wildlife Research Center’s Predator Research Facility are engaged in long-term research projects to place, support, and evaluate the use of LGDs with sheep and cattle producers in the western states. In Texas, experts from Texas A&M University have also instituted an expanded research project center around the use of LGDs with goat producers. As with the USDA researchers, the goals are to place LGDs with ranchers who have not used them previously on their large pastures and to provide training and support for the users. Elsewhere research continues on other methods of nonlethal protection.

The following techniques not only protect your animals but also fit the guidelines of the Wildlife Friendly Network (see here).

Sheep Production |

|

|

Nonlethal Control Methods |

Percentage of producers using method |

|

31.8 |

|

|

LGDs |

23.5 |

|

Lambing sheds |

20.0 |

|

Night penning |

19.5 |

|

Culling older sheep |

9.6 |

|

Frequent checks |

9.5 |

|

Guardian donkeys |

8.2 |

|

Remove carrion |

6.6 |

|

Sheepherding |

6.4 |

|

Changing bedding |

6.3 |

|

Guardian llamas |

5.4 |

|

Other techniques |

3.9 |

|

Change breeding season |

2.9 |

|

Fright tactics |

1.8 |

Sheep and Lamb Predator and Nonpredator Death Loss in the United States, 2015 (USDA, September 2015).

Cattle Production |

|

|

Nonlethal Control Methods |

Percentage of producers using method |

|

Guard animals |

4.1 |

|

Fencing |

3.8 |

|

Frequent checks |

3.7 |

|

Culling |

3.0 |

|

Carcass removal |

2.5 |

|

Night penning |

0.8 |

|

Herding |

0.6 |

|

Fright tactics |

0.3 |

Cattle and Calves Predator Death Loss in the United States, 2010. (USDA, February 2012)

Fencing is always the first line of defense in predator protection. Keeping stock in is usually easier than keeping predators out, and fences are often designed for that purpose only, not for protection.

Fencing is often divided into two types — exclusion and drift. Exclusion fencing is designed to keep specific wildlife out. Drift fencing is usually intended to keep specific animals in but often does not provide good predator protection, especially such choices as board and rail, widely spaced barbed or electric wire, and nonelectrified wire.

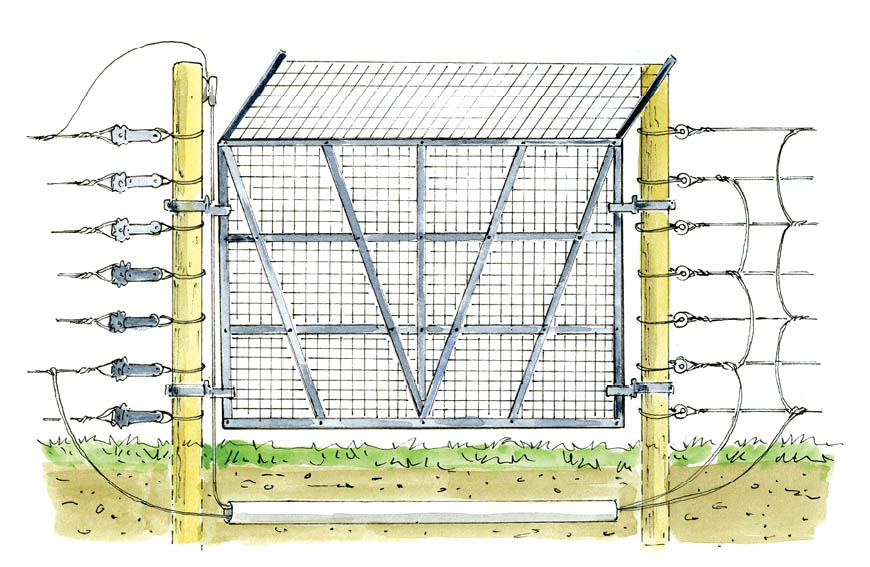

Fences that do provide predator exclusion include wire mesh with narrow spaces, multistrand electric fencing, or a combination of these materials. Poultry and small animal fencing in particular needs to be very tight and often utilizes heavy mesh wire screening or hardware cloth, underground aprons, and overhead protection of runs. Properly selected and designed temporary fencing, such as electric tape, wire, rope, or electrified net, can also provide good predator exclusion.

The higher cost of such fencing is justifiable when you are experiencing high losses, large or dangerous predators, or loss of valuable animals. Good predator exclusion fencing will also increase the success of your other prevention techniques, including livestock guardian animals.

Some owners choose to create a zone of greater safety to house animals at night or during times of greater vulnerability. Your fencing plan can include choices such as exclusion fencing for boundary areas and drift fencing for interior areas. Others choose to create very secure nighttime shelters and paddocks. The same guidelines are relevant to owners who wish to protect their yard and areas around their home site.

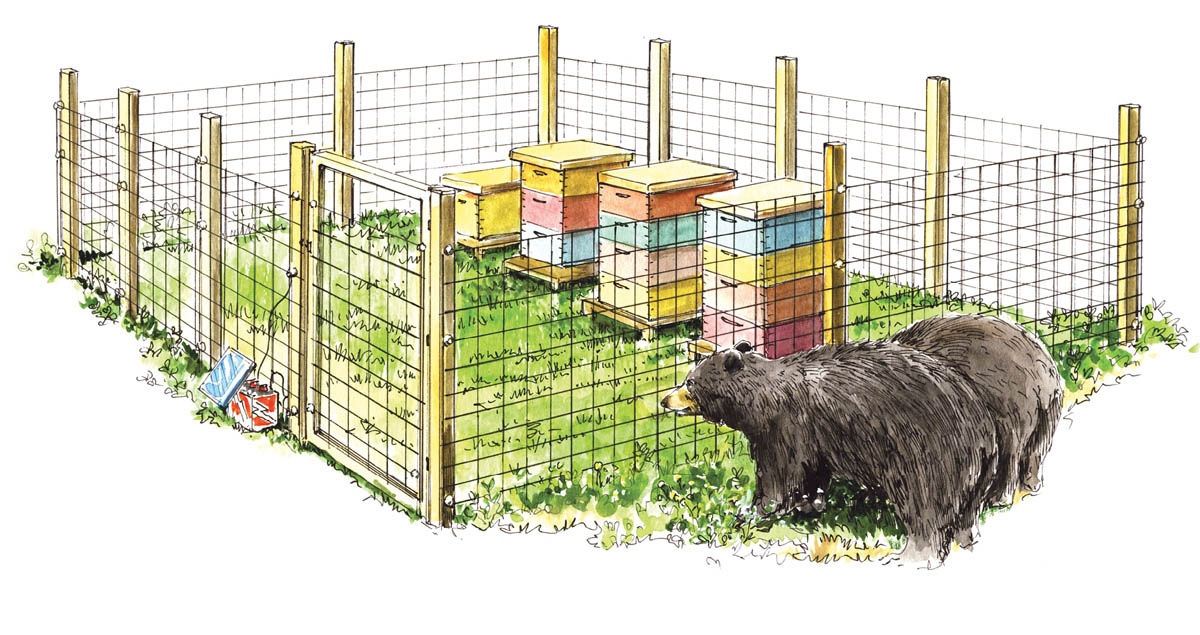

Consolidating your beehives makes the use of bear-resistant fencing more practical. A well-protected and maintained bee yard provides nearly complete security

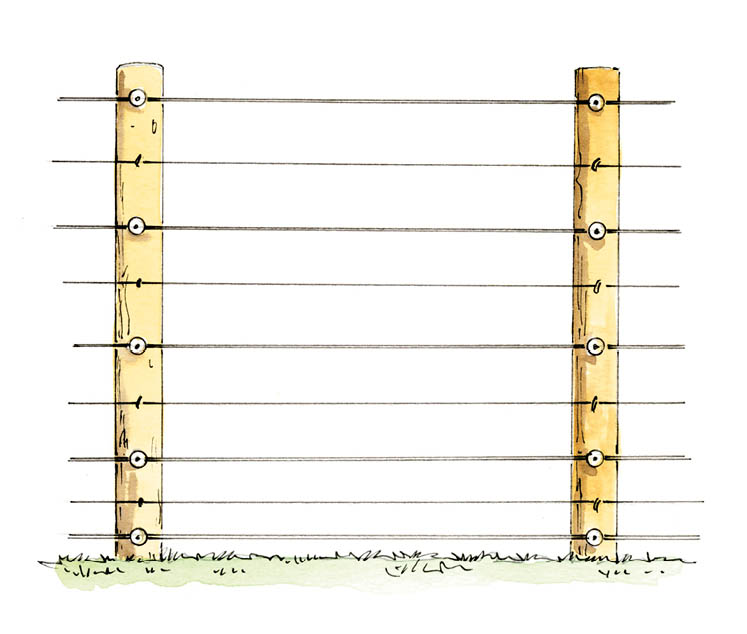

Why choose it. Wire mesh or woven wire provides several advantages. It serves as a physical and visual barrier and remains effective in power outages.

Tips. The size of the mesh itself and the height are important for specific predator exclusion and stock or dog inclusion. Mesh fencing is available with tighter or smaller bottom mesh for increased predator proofing. Heights of 5.5 to 6 feet tall are highly recommended, but additional electric wires placed 1 foot above a 4- or 5-foot-tall mesh fence will provide good predator exclusion. Adding an electric trip or scare wire on the outside will also prevent digging. If you use LGDs, you can place a scare wire on the inside to prevent digging by a dog as well.

Install mesh fencing tight to the ground and on the inside of the fence posts. Gauge refers to the wire size — the larger the number, the smaller and weaker the wire. The different knots used to link the mesh have different characteristics as well.

Best choice. Mesh fencing can be poly-coated or galvanized for longer life. Although more expensive, high-tensile mesh fencing has a longer life span, less sag, and can be strung farther between posts. Galvanized, high-tensile wire is recommended for predator control.

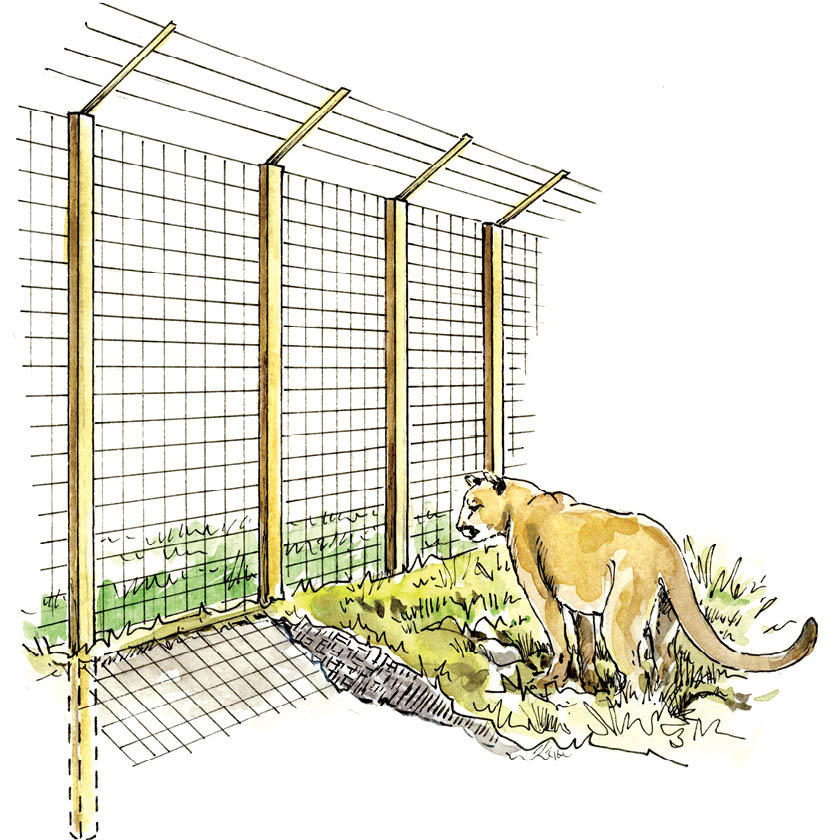

Coyotes, wolves, bobcats, lynx, and dogs can jump fences shorter than 6 feet tall. Mountain lions can present a greater challenge since they can jump a 10-foot fence. Coyotes can pass through openings as small as 4.5 inches and can often crawl or dig under the bottom wire or under a fence.

Raccoons and some other small predators are excluded by 2- or 3-inch-wide openings, but they can reach through 1-inch openings such as those found in chicken wire.

Bears are often more discouraged by electric fencing than by physical fences unless those are quite substantial, such as livestock panels.

Some questions to consider:

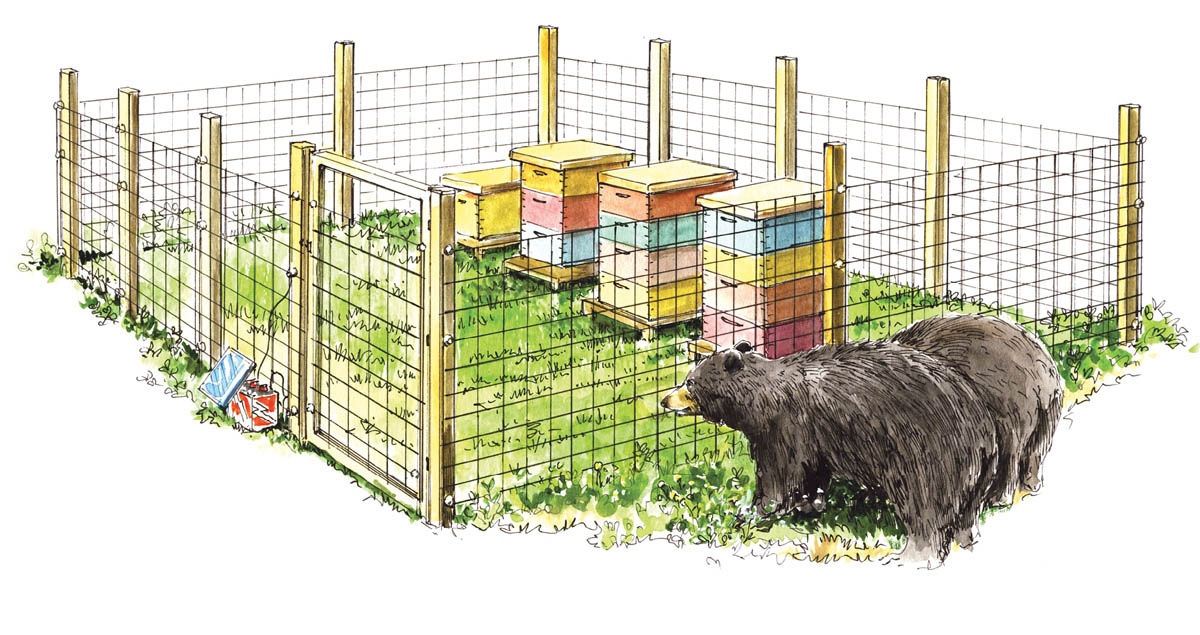

Why choose it. Electric fencing is often less expensive than mesh fencing and easier to install on rough ground. On the other hand, it is less visible to animals, requires regular inspection or maintenance, and is not as effective if the power goes out or the fence is shorted. Maintenance is a continual issue.

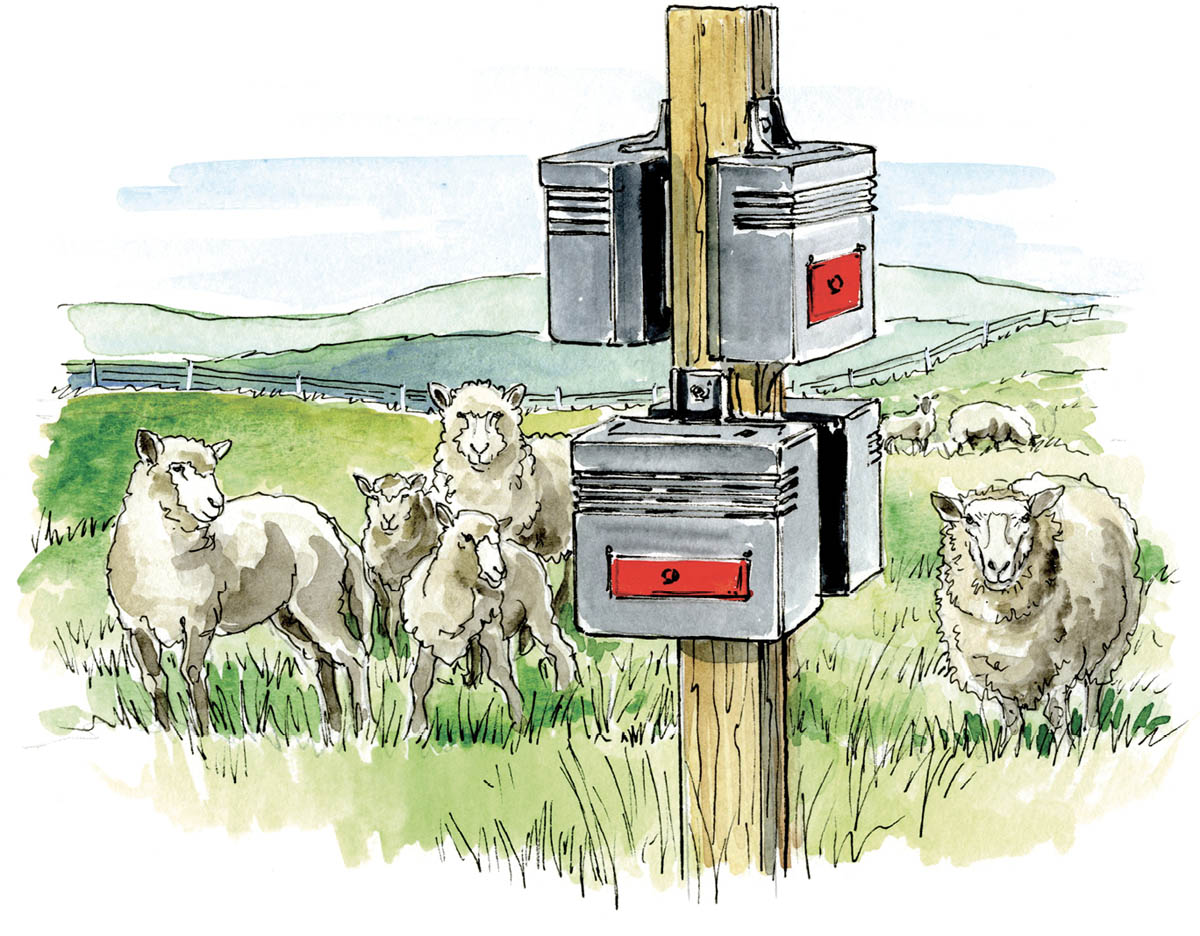

Tips. The effectiveness of the electric fence is dependent on the voltage, the energy of the pulse, and the degree of contact. The electric fence charger or energizer converts electric power into high-voltage pulses. Energizers can be powered by solar cells, batteries, or the domestic power system. Most chargers are the low-impedance, solid-state type that do very well in moist soil and will shock through green vegetation. Low-impedance chargers work well with large stock. Wide-impedance energizers deliver higher voltages, especially in situations of dry soil, and work better as both predator deterrence and containment for animals such as goats or poultry. The older high-impedance, or “weed-burner,” chargers are more likely to cause fires in very dry conditions and are less effective with animals such as goats, sheep, and poultry.

An electric fence is essentially an open or incomplete electric circuit until it is grounded by an animal touching the fence, which allows the pulsing electricity to travel through its body into the soil to the nearest grounding rod and then back to the energy source. Snow can prevent animals from making contact with ground, and frozen soil doesn’t conduct electricity well. Where dry soil, frozen ground, rocks, or snowpack exists, more intense shocks are delivered from “hot/ground” systems that use alternating wires — a charged wire and an uncharged wire are connected to the ground terminal. This grounded wire is a better conductor than soil, delivering a stronger shock. An animal needs only to touch both the charged and the grounded wires to complete the circuit.

Electric fence systems require grounding and lightning protection. All electric fences should be clearly marked to reduce accidental shocks.

Best choice. To discourage predators, an electric fence needs at least 5 wires; increasing the number of wires and the height will create more substantial predator protection. Spacing the wires closer together near the bottom portion of the fence will also help exclude small predators and coyotes. A 6-foot-high, 9-wire fence is an effective predator exclusion fence, with 13 wires providing near-absolute protection. Besides wire, electric fences can be constructed with electric braid, rope, or tape — all of which are more visible than wire to animals. Electrifying barbed wire is considered too dangerous because the barbs can snag people or animals, preventing them from escaping the shocks.

Good predator exclusion uses either tightly woven mesh with the addition of electric wires above and a trip wire outside the fence, or closely spaced, multiple-wire electric fencing.

Since mountain lions (also called pumas) can jump 10 feet high, fences need to be at least 12 feet tall. Heavy woven wire or chain link are more difficult for mountain lions to climb. A wire mesh or electric overhang at the top of the fence is also important. Clear all overhanging tree branches.

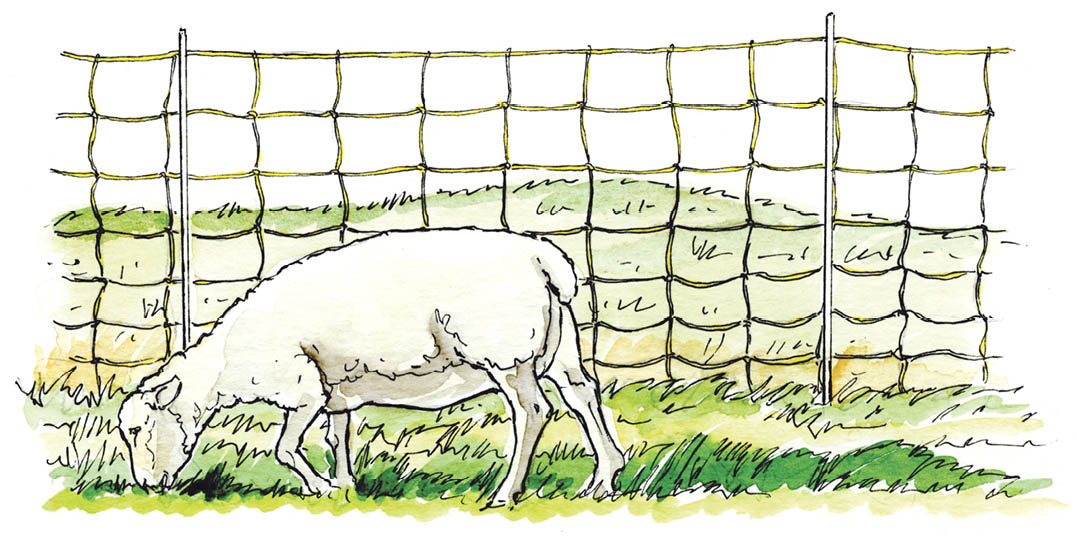

Why choose it. Temporary fencing is most often used to keep stock in a designated grazing area or to create a more protected area for night penning or birthing. It is also useful to contain free-range poultry and to protect beehives and gardens.

Tips. Temporary fencing can be high-tensile wire, poly wire or tape, or poly mesh. Fencing comes in different heights and spacing for specific stock, poultry, or predator applications. Temporary chick fencing is designed to be no-shock. Sagging is reduced with the use of additional vertical struts or posts.

Best choice. Electric netting is the most predator-proof fencing for temporary situations. It will contain sheep, goats, poultry, or dogs and protect against bears, coyotes, bobcats, roaming dogs, raccoons, and other small predators.

It is more reliable and faster to install and move, but it is also more expensive than conventional electric fencing in temporary situations.

Electric netting is a fast, portable, and versatile alternative for predator protection.

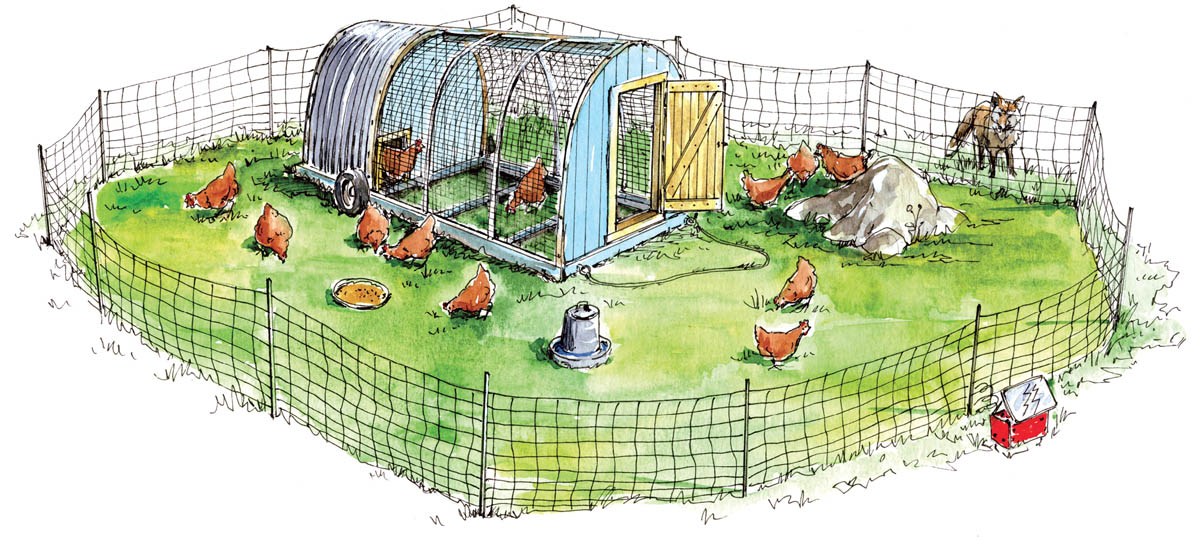

The idea of free-range poultry roaming your yard or farmstead makes a bucolic image; free-range birds, however, are at the greatest risk of predation by roaming dogs and other predators. Even in urban and suburban areas, poultry are very vulnerable to predators. If your birds are more pets than livestock, you must seriously consider how to protect them. Whether you are keeping a few birds or raising larger numbers for meat or egg production, consider one of the following general methods of housing and husbandry.

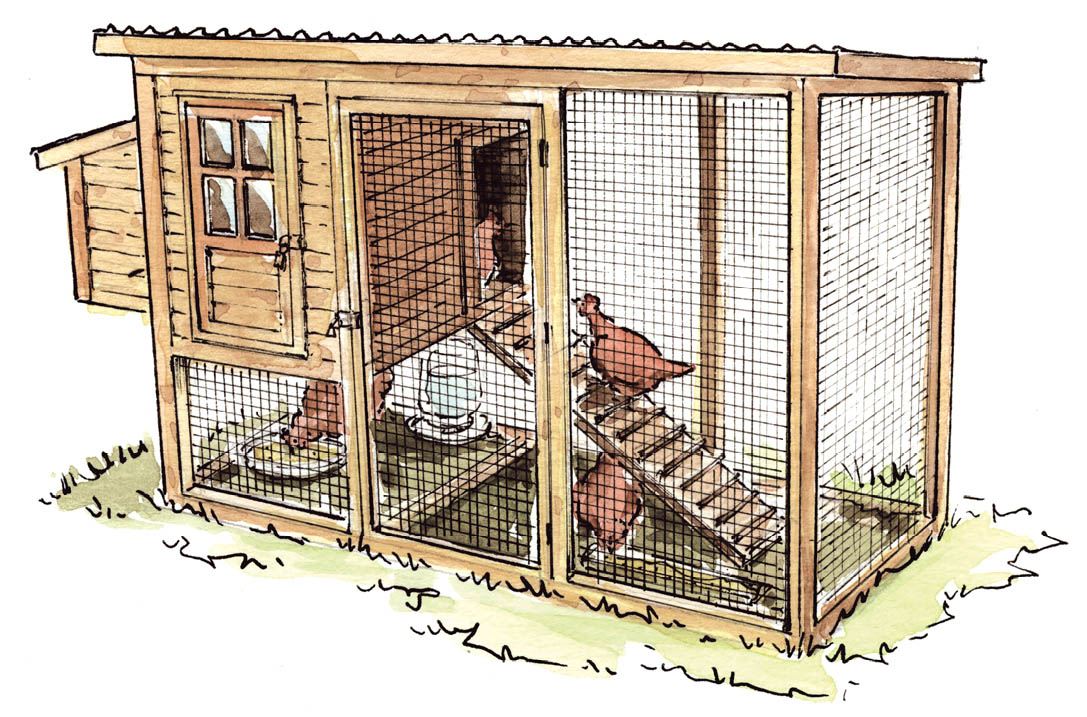

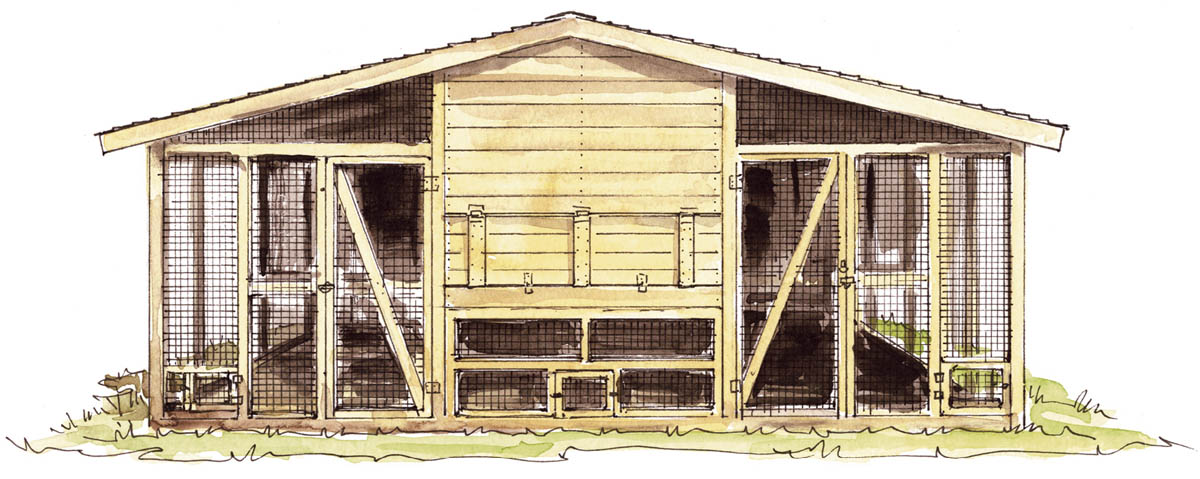

The best way to protect your poultry from predators is to secure them day and night in a predator-proof coop and pen located close to human dwellings, with guardian dogs that will sound an alarm if there is an incursion. Roosters, geese, or guinea fowl can also provide alarm services.

Raise the coop off the ground, if possible. Do not plant landscape plants next to the coop or the pen. A raised coop and a cleared area reduce the ability of predators to reach the structure or to hide next to it. This also allows your cats or dogs to patrol under and around the coop to deal with rats, snakes, and other small predators.

The coop needs solid, rat-proof flooring. Have lights you can turn on if you do not leave them on all night. Use only predator-proof latches or lock them closed with a carabiner or something similar, as raccoons can operate most simple closing systems. Owls and hawks will fly into open coop doors, and owls will walk into them as well. If you are not home to close the coop door at dusk, automatic door openers are available using light sensors or timers to shut the door at dusk and open it after dawn.

Chain link, typical farm mesh fencing, and chicken wire are not predator-proof protection for coops or pens. Small predators such as raccoons, weasels, opossums, or rats can easily reach through these materials. The ideal material is 19-gauge hardware cloth or poultry fencing with 1⁄4-inch holes (or no bigger than 1⁄2 inch). Use hardware cloth over all windows, doors, gates, open spaces under roof rafters, or methods of ventilation.

To prevent predators from digging under the fencing, you can lay a cement floor, hardware cloth, or closely space livestock panels over the entire surface of the pen and cover with dirt, sand, or deep litter. Run the hardware cloth up the wall or fence of the enclosure. If this is not practical, bury hardware cloth in a trench at least 18 inches deep around pen. Cover the entire top of the pen as well.

The well-designed backyard coop and pen should be tightly enclosed with hardware cloth, with a secure bottom and top.

A compromise to a secure coop and pen is to allow birds out to forage during the day and then to secure them at night. Train young birds to return to their coop each evening by keeping them inside their coop exclusively for the first few weeks and by enticing them to return with special feeding right before dusk. They will then consider it their home. Don’t feed outside the safe enclosure, as it will attract rodents, snakes, crows, as well as larger predators.

During the day, turn birds loose only in an area with a predator-proof perimeter fence at least 5 feet high, preferably topped by electric wire. An electric scare wire outside the fence is also helpful to discourage dogs, coyotes, or foxes. Do not allow branches to overhang the fencing, providing climbing opportunities to small predators. Trees and fence posts can both allow raptors to perch.

Five-foot-tall fencing will keep most chickens in, although some can fly 6 to 7 feet. Clip flight feathers on their wings to prevent this.

Electrified netting can enclose chickens and exclude small predators. Grid systems of wire, monofilament, or Kevlar cord, plus netting, will exclude birds of prey from larger areas.

Free-range poultry are more vulnerable to predators than are securely cooped birds, especially if they have to find their own shelter from predator attacks. If you are committed to pasture-raised poultry, several measures can reduce predation while balancing the cost of predator proofing:

Movable coops or chicken tractors, with or without protected forage pens, provide more protection and reduce predator familiarity with location. It can be harder to predator-proof chicken tractors on uneven ground. Fixed coops in the field can usually be made more secure at night either by closing the birds inside or by using electric mesh to surround the area. Netting to prevent baby birds from escaping or becoming trapped in the electric mesh is available.

Training LGDs to protect poultry safely presents a challenge because poultry are not their traditional animal to guard. They do not tend to bond to them as they do to stock. Supervision and time are required. An alternative is to allow LGDs to patrol around poultry coops, pens, or free-range areas. Some large producers have created alleyways around the entire free-range area for the dogs to patrol.

Portable electric mesh fencing can be placed around movable chicken tractors. For added safety, secure the poultry inside the tractor at night.

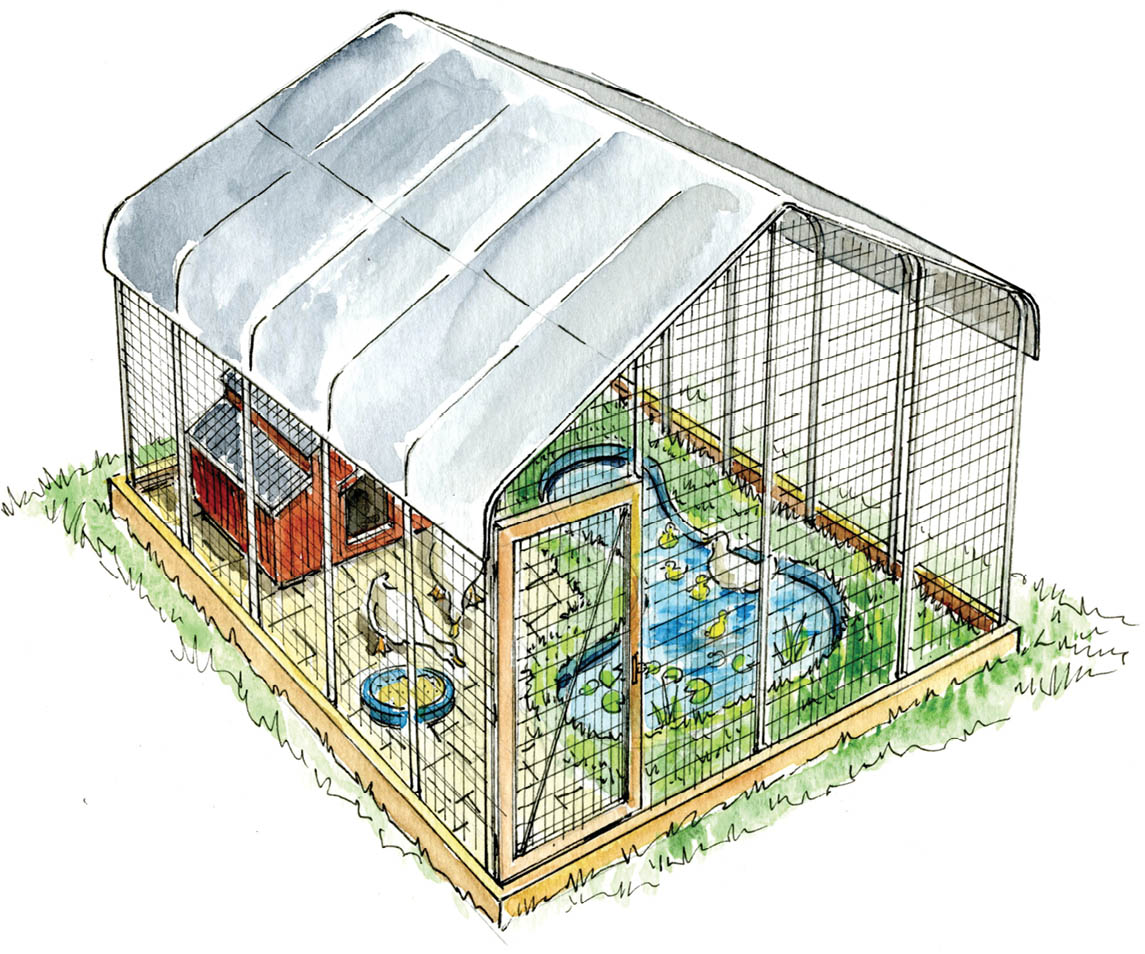

Ducks and geese can be kept in traditional coops, or adaptations can be made for providing water access for the birds by completely enclosing small pools or ponds, including a roof. Ducks and geese can also be fenced, although flying breeds may need their wings pinioned or flight feathers clipped. Electric wire on top and scare wire or buried mesh will keep out many predators. Adult weeder geese are often confined in 20- to 30-inch poultry netting. If waterfowl are kept free-range with access to ponds or waterways, the predator danger increases.

Secure housing for waterfowl includes a predator-proof foundation, fencing, and a roof.

Outdoor hutches are healthier for rabbits or other small animals as long as they provide weather and predator protection. Hutches should be raised on legs or hung above the ground. Some rabbit raisers use LGDs to patrol the hutch area. Ensure that doors and latches are raccoon proof. Don’t allow vegetation to grow under or next to the hutch. Placing the hutches inside a predator-proof fenced area provides increased protection.

Premade cages or hutches can be reinforced for predator protection. Although the holes in the bottom and sides of the hutch need to be large enough for feces to fall through, they often allow access for rats, weasels, opossums, raccoons, and other predators. Hardware cloth with 1⁄2-inch square holes can be stapled over these areas, but it may necessitate cleaning out the hutch more often.

Combining several hutches or building larger pens can house rabbit colonies or groups of rabbits living together. Concrete is the most secure flooring; however, many owners prefer dirt. To protect dirt colonies, perimeter fencing must run 3 feet underground to accommodate dens and tunnels and to prevent the rabbits from digging out or predators from digging in. The sides and top of the colony need to be predator-proofed as well. Larger colonies kept on pasture are harder to protect from aerial predators, although they can be fenced to prevent other predators. Truly free-roaming rabbits are at the greatest danger.

Rabbit tractors generally have floors constructed of wood or aluminum slats 11⁄2 to 2 inches apart or wire mesh to prevent rabbits from digging out and yet allow for grazing. The sides need to be covered with hardware cloth. Rabbit tractors need to be heavy enough that predators can’t tip them over. Some owners use LGDs in the area of rabbit tractors, or they bring the rabbits into a building or more secure pen at night.

To provide protection from these predators, animals need to be in fully enclosed housing. Free construction plans are available at mountainlion.org.

Permanent poultry housing can be designed for both function and protection from even the largest predators, providing housing for separate groups of birds, easy collection of eggs, and daytime free-ranging.

We know several key points about predator attacks on grazing animals:

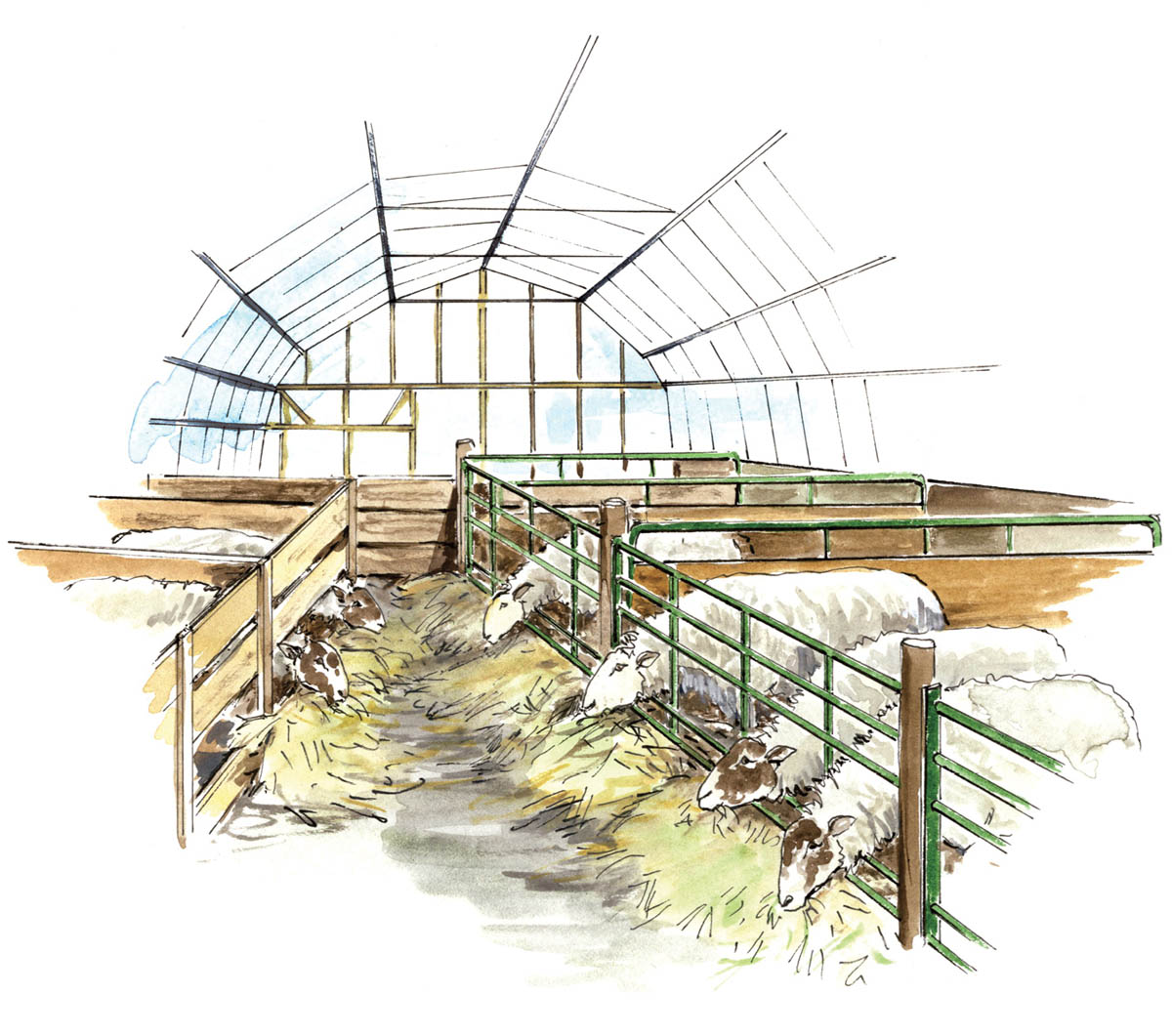

Indoor lambing sheds protect animals at their most vulnerable time.

Thorough recordkeeping will give you insights into time and location of predator attacks on your property. Paddocks and areas closer to the farm center can be made more secure for birthing, nighttime, and winter confinement. Timed or synchronized breeding schedules can make this more manageable. In some cases, stock needs to be securely sheltered every night in predator-proof housing. Some producers move to indoor lambing sheds.

Rotate your pastures to accommodate predator pressure, and choose safer or sheltered areas for vulnerable times such as birthing. Move grazing away from wolf-occupied areas during calving or lambing, if possible. On very large pastures or on open range, create temporary and protected small areas for calving and lambing, especially at night. Remove dead, sick, or injured animals. Move weak lambs and calves and abandoned newborns to jugs or individual pens with their mothers or to more protected areas. Bury and compost afterbirth and stillborn animals, to keep domestic animals from developing a taste for them and to keep scavengers away. Groups of producers can work cooperatively to keep range areas free of carrion.

Plastic protective collars may prevent a predator from biting or grasping the jaw area and under the neck.

The ancient technique of human interaction and supervision of grazing stock is still very valuable and has been proven effective against predators. Wolves and coyotes tend to stay away from areas with a human presence, even if it’s only part-time presence. Either full-time shepherds working with their herding dogs and LGDs or range riders using horses or ATVs can deter predators and allow for the practice of good husbandry.

Humans can patrol at dawn and dusk when predators are active; check for predator signs such as tracks, scat, and upset animals; and even track wolves with radio collars to determine locations. People can support LGDs working with the stock by keeping the animals closer together for grazing rather than widely dispersed. Herders can move stock away from threatened areas as well as monitor range conditions to maintain the health of grazing land. On open range or large pastures, stock can be confined into more protected temporary pens of electric fencing or paddocks at night or at times of great vulnerability such as birthing.

Disruptive methods include visual, auditory, and other repellant techniques. Aversive methods work to condition a predator against engaging in a specific behavior. Both methods are more useful and successful when combined.

Range riders not only deter predators but also gain valuable information on their stock and provide a rapid response to new situations.

Frightening and scare devices are old practices that can be adapted or improved today. A great value of these devices is that they can be used immediately after an attack or predator sighting or during more vulnerable times such as calving or lambing. The greatest disadvantage is habituation, which means the predator becomes used to the stimuli and begins to ignore them. Changing and moving the stimuli increase their usefulness.

Night lighting is useful over corrals or pens, poultry housing, and around buildings. Light is effective in discouraging coyotes and other predators but not as effective with roaming dogs. Night lighting also allows an owner to check on stock with more ease. No proof supports the idea that strobe lights work better than regular lights; however, motion-activated lights are more effective than regular lights, as are novel or changeable patterns. Lighting can include flashing, rotating, regular, or search lights. Lights can be placed on timers for ease of use; that is, they will come on automatically even when you’re not there. Lasers are generally used to deter pest and flocking birds rather than predators.

Nite-Guard lights use flashing red lights that mimic the eye shine of another predator and remain effective in fog and similar conditions. Fox Lights simulate the random pattern of flashlights. Lights like these are useful against nocturnal predators, including owls.

Visual deterrents include Mylar tape and balloons, aluminum pans, and similar materials. Mylar tape moves, flashes, reflects sunlight, and can produce a clicking or humming noise. Mylar tape is available in different widths and can be hung as streamers or stretched between posts. Mylar or plastic balloons can be filled with helium so they float or filled with air and suspended. Some balloons are printed with large eyespots.

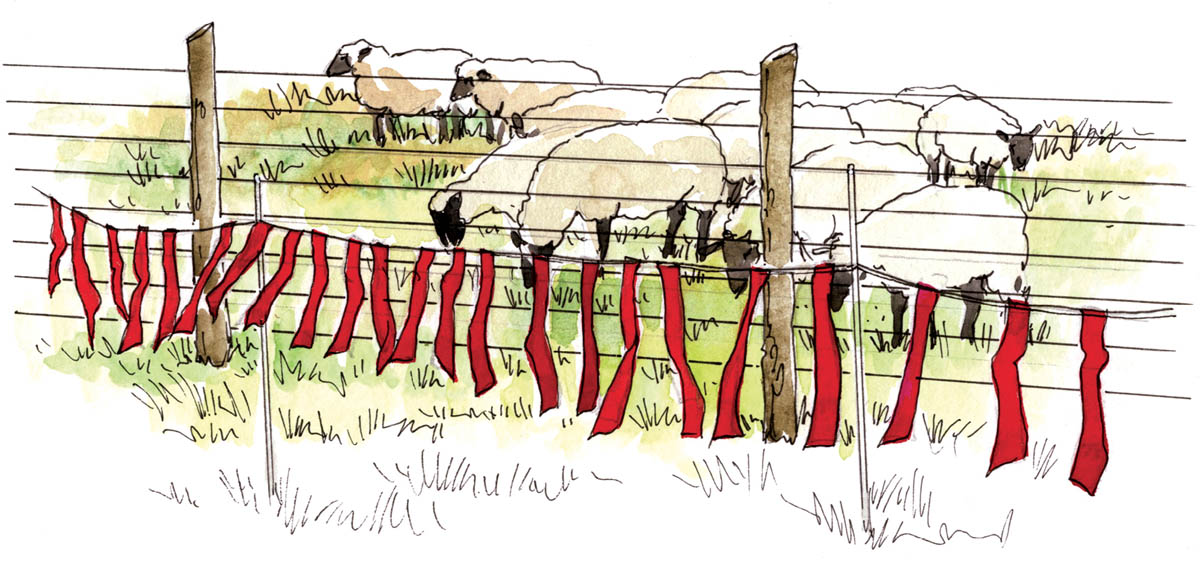

Fladry. A rope line of flags, pendants, or streamers, fladry is used to discourage birds of prey and wolves in particular. Flags moving in the wind add stimuli to an existing fence or function as a temporary fence or barrier against predators. They are very useful around calving or lambing grounds on open range, overnight pens on larger grazing lands, or grazing areas during periods of higher predator pressure.

The recommended installation is outside of the existing fence line on a separate rope line and posts. Since wolves are more likely to go under fladry than to jump it, the bottom of the flags should be 6 to 8 inches off the ground. The rope line itself is generally 15 to 24 inches high. The line needs to be taut, a consistent height, and avoid brush. At times, existing fence, trees, or natural objects can be incorporated into a fladry line. Larger flags or fabric panels may be more effective. Wolf vision is very motion sensitive, but wolves do not see the same range of colors as humans see. Red-, orange-, and gray-colored flags have been tested, but color may not be important. Plastic caution tape or nylon pieces and mason line can be used to create a homemade fladry. Nylon is more durable, and stock may chew the plastic. Fladry is still under development, and improvements should continue.

Turbo or electrified fladry is 2 to 10 times more effective than regular fladry, with a longer period before habituation. It also provides protection at night. The cost is approximately twice that of regular fladry. Installation requires greater care to avoid touching ground, brush, or objects that will ground out the fence. Turbo fladry is especially suited to smaller pastures, overnight penning, and calving or lambing pastures.

Commercial fladry is not yet widely available; fortunately, homemade fladry is also very effective. The fladry rope should be strung as tightly as possible.

Scarecrows and effigies of owls or vultures. Scarecrows can be static, mechanical (they pop up and move), or inflatable with noise and light cycles. Scarecrows that twist in the wind, move their arms, and wear human clothing can be effective for up to 3 weeks, and then you’ll need to move them elsewhere.

Plastic effigies of owls can be static, or the wind can turn the head. Research has shown that effigies of dead vultures hung where damage is occurring will repel black and turkey vultures.

Music, especially with bass or talk radio, has unpredictable rhythms and sounds like human voices. Recorded sounds include alarm or distress calls, dogs barking, gunfire, human screams, music, predator calls, or synthesized sounds. Recorded sounds can be species-specific. Some commercial sonic units are programmable and include lights, and additional speakers can extend coverage.

Horns, sirens, and propane cannons should be set to go off every 8 to 10 minutes or at random intervals, and they should be moved every 3 to 4 days. Gunfire and fireworks are labor-intensive, temporary, and best used only in response to the immediate presence of a predator.

Using bells on livestock is a traditional method of noise deterrence. One study asserts that coyotes and bears do not attack the belled animals in a flock or herd. Some bear specialists assert that bells now attract bears, and they discourage hikers from wearing bear bells. Predators are likely to habituate to belled stock but if combined with other aversive methods, such as LGDs, bells may condition predators to avoid a particular group.

The traditional practice of belling some members of a flock or herd still has merit, especially if the predator also encounters other disruptive or aversive responses to attacking belled stock. The loud noise made by a belled animal in flight may also discourage an attack.

No proven carnivore repellents are available, although several compounds are being tested. The following are some traditional methods:

Various wildlife agencies are testing combination systems in specific situations.

This system uses lights and sound activated by radio-collared wolves, bears, or mountain lions. Tracking these collared animals can also alert owners to the nearby presence of a major predator so that extra precautions can be taken.

This system uses an infrared detector with light and sound response.

Aversive methods condition a specific predator not to perform a behavior, such as stalking or attacking poultry or livestock. Aversive techniques include the use of hazing, multispecies grazing, livestock guardian animals, hard release of problem animals, and bear shepherding with Karelian bear dogs (see box, Karelian Bear Dogs).

The act of disturbing an animal until it leaves, hazing employs multisensory techniques — visual and auditory — as well as threatening or aversive behaviors. While the public is encouraged to haze coyotes, the hazing of bears, mountain lions, or wolves can be more dangerous and is often left to experts, although individuals should employ these techniques if confronted by an animal. See Coyote Hazing Tips.

The use of guardian llamas and donkeys is basically a form of multispecies grazing. Other animals such as cattle or horses can also offer protection to smaller stock, although often the different species are not inclined to graze together.

The term flerd describes a multispecies group that has bonded together through penning for 30 to 60 days. Horned cattle can be especially effective in a flerd. Consider identifying and incorporating a few of the more aggressive and protective ewes or cows, even if they are more difficult to handle or less productive. Rams, bucks, and bulls are naturally more protective and aggressive. Even one or two larger animals will help protect smaller animals, such as sheep or goats.

Livestock guardian animals offer many advantages. They are very alert to potential threats. Predators do not become habituated to their responsive attacks, which are both disruptive and aversive. The use of livestock guardians is also considered a predatory-friendly marketing approach.

In sheep operations, the use of livestock guardian animals is the second most common nonlethal method of predator control, after fencing. Approximately 37 percent of sheep raisers use guardian animals, with LGDs the most popular choice (23.5 percent), followed by donkeys (8.2 percent), and llamas (5.4 percent). The use of both LGDs and donkeys has more than doubled in the last decade, as their value has been proven.

LGDs are a very old partnership dedicated to protecting sheep, goats, or other stock. Selected over hundreds of years, these breeds have a low or nonexistent prey drive, a longer period of social bonding to stock, and a physical appearance that suggests friend not wolf to animals. LGDs possess instinctive responses and behaviors to threats. The specific breeds of LGDs were developed over an area from southern Europe through Central Asia — specially to protect sheep and goats from large predators. The use of LGDs has been shown to reduce predation by 60 to 70 percent or more.

Shepherds lived and worked together with their LGDs in their homelands. All LGDs are raised with human or older dog supervision. It is a myth that livestock guardian animals should be raised with minimal human contact. While they need extensive socialization to stock, all livestock guardians need to be safe to handle and care for. Without regular handling, guardians will become uncontrollable and nearly feral.

Research has shown that LGDs are more effective when farmers or ranchers work directly with the dogs and do not leave them alone to guard stock. Dogs are the least successful when asked to guard stock dispersed over a large area, in very rough or wooded areas, and where owners have spent only minimal time with the dogs. Ideally, LGDs should be established with their stock before peak predator times and before the predators establish a territory. Wolf attacks are more successful when dogs are outnumbered, when the dogs are placed in an already established wolf territory, or when people are not present to provide support during an attack. A single dog is more likely to accept or tolerate a wolf than packs of dogs will be. Most important, livestock or poultry owners need to be proactive and not wait until after an attack to begin looking for a fully trained adult dog. Using LGDs successfully requires the commitment to obtain, raise, and train good dogs as insurance against future needs.

LGDs patrol and mark their territory. They are active at night during the time of greatest predation and will bark to warn off potential threats and to alert their owner. The dogs are self-thinkers and will work cooperatively in pairs or packs to both defend the stock and charge the predator. LGDs employ a graduated response to predators — barking, posturing, and charging usually drives the threat away — and they attack only when the predator does not leave. LGDs can be used in situations with the most dangerous predators. Both females and males are equally effective.

The most important factors in achieving an effective livestock guardian include choosing a dog from working parents who are both recognized LGD breeds, providing good socialization to stock, and giving positive training and supervision until the dogs are reliable. Guarding poultry is the most difficult task for LGDs and not a traditional one in their homelands. Guarding equines can also be problematic if the horses or donkeys have a strong antipathy to dogs.

LGDs have been protecting livestock for more than 2,000 years. In their homelands, LGD pups are never left alone with stock, but are carefully supervised and trained by shepherds and older, experienced dogs.

Karelian bear dogs (KBDs) are hunting and watchdogs originating in a large area of the northern latitudes from Scandinavia into Siberia. They have demonstrated significant value in deterring grizzly bears and other large predators such as mountain lions. Since the 1990s, the nonprofit Wind River Bear Institute, founded by biologist Carrie Hunt, began training handlers and KBDs for both black and grizzly bear conservation and other nonlethal predator control efforts. Karelians are trained for use with bear management specialists, trained volunteers, and people in bear country. KBDs have three essential roles: bear conflict dogs for management specialists, rangers, or wardens; bear protection dogs for biologists, ranchers, or outfitters; and companion dogs for hikers and others.

Trained KBDs and handlers are used in some US and Canadian national parks and in several western states or provinces. KBDs are used to push or shepherd bears out of human conflict areas, both urban and recreational, including camping areas and residences. The dogs are used in conjunction with aversive conditioning techniques such as bells, firecrackers, and pepper spray in structured experiences to teach bears to recognize, fear, and avoid human areas. This conditioning is often used in a “hard release” of a problem animal. KBDs are also used to locate, track, and assist with removal of problem or injured animals.

KBDs bond closely to their owners yet can be quite independent in their decision-making. Karelians have a high prey drive and a strong desire to chase. Owners report that they easily jump 6-foot fences and will do so in order to hunt. Karelians are strongly territorial, protective, and dog aggressive. When working they are courageous, intense, and focused. They are not generally well suited as a pet, especially in urban environments.

Not LGDs, Karelian bear dogs are used to haze bears away from human conflict areas.

LGDs comprise a specific set of breeds, not a job. Only livestock guardian breeds and crosses between these breeds possess the proper instinctual behaviors, protectiveness, nurturing nature, size, and coat to work as full-time livestock guardians. You’ll notice some size, coat, and behavioral differences among breeds, and some breeds are more reactive or defensively aggressive while others are more tolerant of strangers. Crossbred LGDs are also effective, but only if both parents are from recognized LGD breeds. The following breeds are available in North America.

Donkeys are used less frequently than dogs as guardians. Donkeys are very territorial and strongly aggressive to canines, lending their protection to the animals they live with. They are very alert to potential threats. Donkeys may bray loudly at a disturbance, followed by chasing a canine. If they engage in an attack they will kick, bite, and slash at the intruder. Stock may also see the donkey as a protector and gather near it.

Donkeys are less social than llamas and require a longer period of social bonding with potential charges. A foal raised with sheep or goats is more likely to live well with stock. A jenny with foal is the most protective. Either mature jennies or neutered males can be good guardians, while intact males can be dangerous to stock and humans. Guardian donkeys should be standard sized or larger, since miniature donkeys are too small to deal with many North American predators.

Guardian donkeys should be standard sized or larger. Miniature donkeys are inappropriate to use as a guardian against predators.

Llamas are very social. A single llama will tend to associate with other animals and be protective of them. Dominant males naturally guarded groups of females with young. Some llamas will position themselves between the threat and their flock or will attempt to herd them away. They often place themselves on higher ground to scan for predators and are reliably aggressive to canines. Llamas usually alert to a threat by a high-pitched call, followed by posturing or spitting, followed by kicking or pawing at the attacker.

Llamas may be a good choice for some situations, but they are unable to confront more serious predators. Use only mature adult females or neutered adult males. In North America, alpacas are not appropriate guardians because of their diminutive size against the size of our predators.

The following precautions are useful in all situations, although householders in large-predator habitat need to be extra proactive and careful. Be aware of habituated coyotes, bears, mountain lions, and wolves in your area. Practice recommended hazing techniques around your home and neighborhood. Eliminate shelter, water, and food for both predators and prey. Remember that your yard is a habitat.

Landscape plants that attract deer and/or coyotes vary by area, but some common culprits include:

Deer: snow, service, and elderberry shrubs; cherries, plums, persimmons, strawberries; arborvitae, European mountain ash, rhododendrons, azalea, sea holly, yews; tulips, hardy geranium, candy lily, winter creeper, clovers, and many others

Coyotes: strawberries and other berries, watermelons, sarsaparilla, balsam fir, white cedar

Cats and small- to medium-sized dogs are the most vulnerable, as are other backyard pets or poultry.

Never chain or tether a dog, leaving it vulnerable to predators. A doghouse alone is not a safe refuge from a predator. If a dog is left alone outside, it needs to be enclosed in a well-fenced yard or in a completely enclosed kennel or run.

Build the kennel of well-attached chain link, heavy wire mesh, or livestock panels. Lay a livestock panel or wire mesh under dirt or gravel areas to prevent your dog from digging out and a predator from digging in. Cover the entire top of the kennel with chain link or panels, not a tarp, if there is any danger of predators climbing up and into the kennel area.

A doghouse inside the kennel can provide a place to hide, but the best solution would be an access door into a building or the house. Electronic or magnetic doors are available that only open for a small device on a pet’s collar. Lock this door at other times.

Pet cats can be allowed safely outdoors in securely enclosed porches, pens, and cat runs. Some owners construct a safety cat post made of climbable material (such as sisal rope), 7 feet high with a flat platform on the top.

To prevent your cat from climbing out over the fence, install a U-shaped fence topper or overhang out of small-gauge mesh, at least 2.5 inches square. Also use the mesh to cover any openings or as an apron to prevent digging. Tree guards or baffles are also useful to prevent climbing. This fence overhang may keep your cat in, but it won’t prevent other cats or other predators from getting into your yard.

Where predation on small- to medium-sized pets is a threat, covered runs or pens and a safe retreat indoors are the safest option.

In addition to the threats of disease, mites, and other pests, beehives are highly attractive to some animal predators. Bears are the major threat, capable of causing serious destruction and significant economic loss. A clean, well-tended bee yard will discourage predators and reduce temptations; however, good fencing can exclude raccoons, skunks, and bears. Strapping the hive together and weighing down the top will also make it harder for a predator to take it apart or gain access.

Mice. Install mouse guards to prevent mice from entering the hive, especially before winter. Wooden reducers can be enlarged by chewing mice.

Raccoons. Place a heavy rock, brick, or cement block on top of the hive to prevent raccoons from removing top boards.

Skunks. Raise hives higher than a skunk can reach, up to 3 feet. Place plywood with a nail “pincushion” in front of the hives. Predator-proof fencing, chicken wire, and netting will keep skunks away from hives. Bury wire netting, mesh, or hardware cloth 6 inches down and extending out 6 inches.

Bears. Place electric netting or fencing around the hives, and use sturdy livestock panels for the best combination of deterrents.

Backyard beekeepers can prevent predation by grouping their hives together, surrounding them with closely spaced electric fencing, and weighing down the hive top.