chapter 2

Who’s Out There?

When a livestock or poultry owner discovers the carcass of an animal, it can be emotionally and financially devastating. Owners ask themselves what they could have done differently to protect their animals. Protection begins with an understanding of what threats exist in the place where you and your animals live.

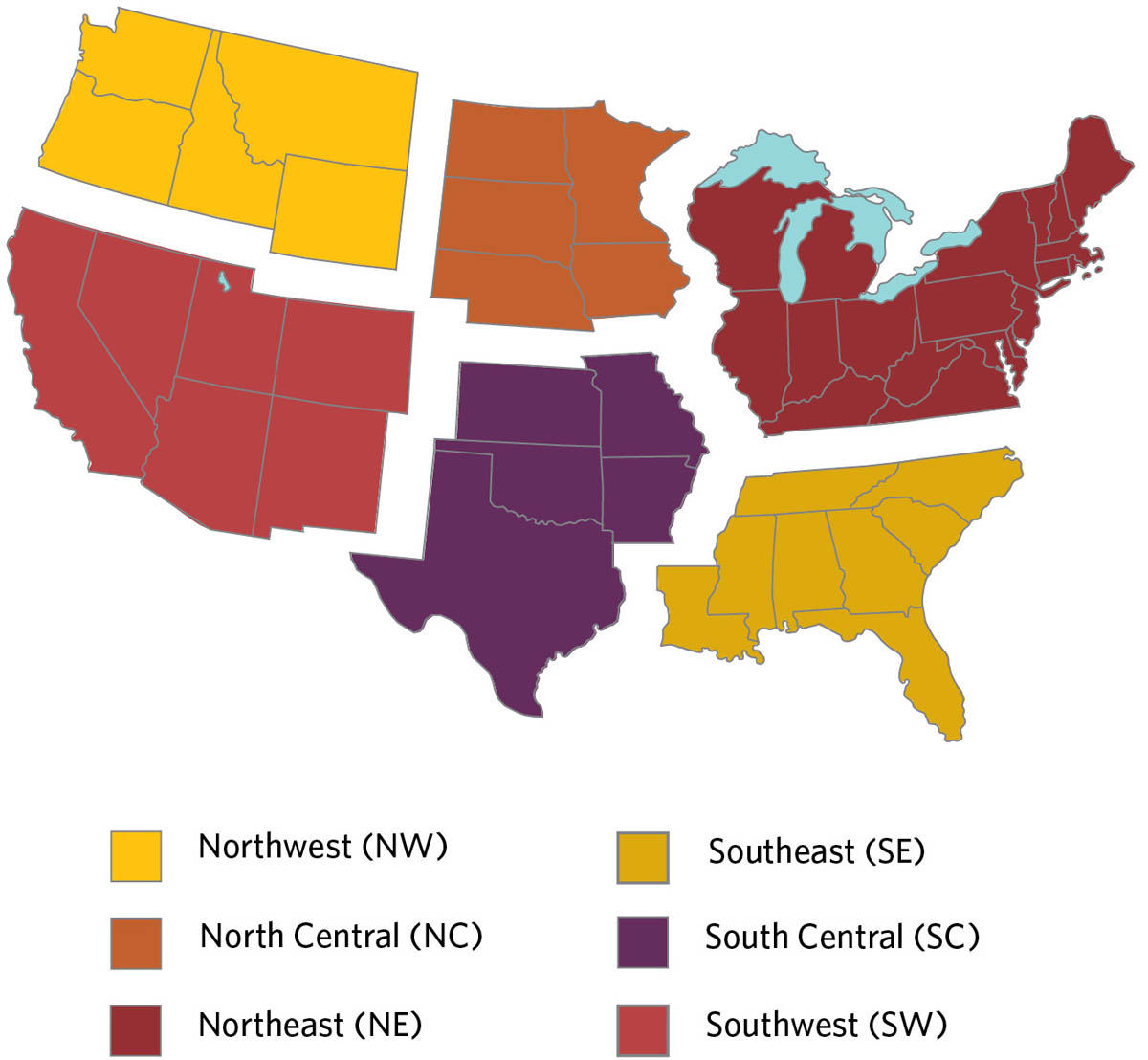

Three factors help to determine your potential threats: the region where you live; your home’s location, from city to suburb to semirural exurb to truly rural area; and finally, the animals you keep, whether large stock or small animals, poultry, or pets. Learning about predator ranges, livestock death statistics, and the migration of predators into suburban and urban environments informs farmers and homeowners alike.

Identifying Likely Culprits

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) tracks adult cattle, calf, adult sheep, and lamb losses through two major reports, with more limited information collected for goats (see box below). This information helps rural and exurban residents determine their predator threats, judge their relative risks according to area of the country, and evaluate the success of various nonlethal predator control methods. It also clearly illustrates the scope and impact of predation on livestock and their owners.

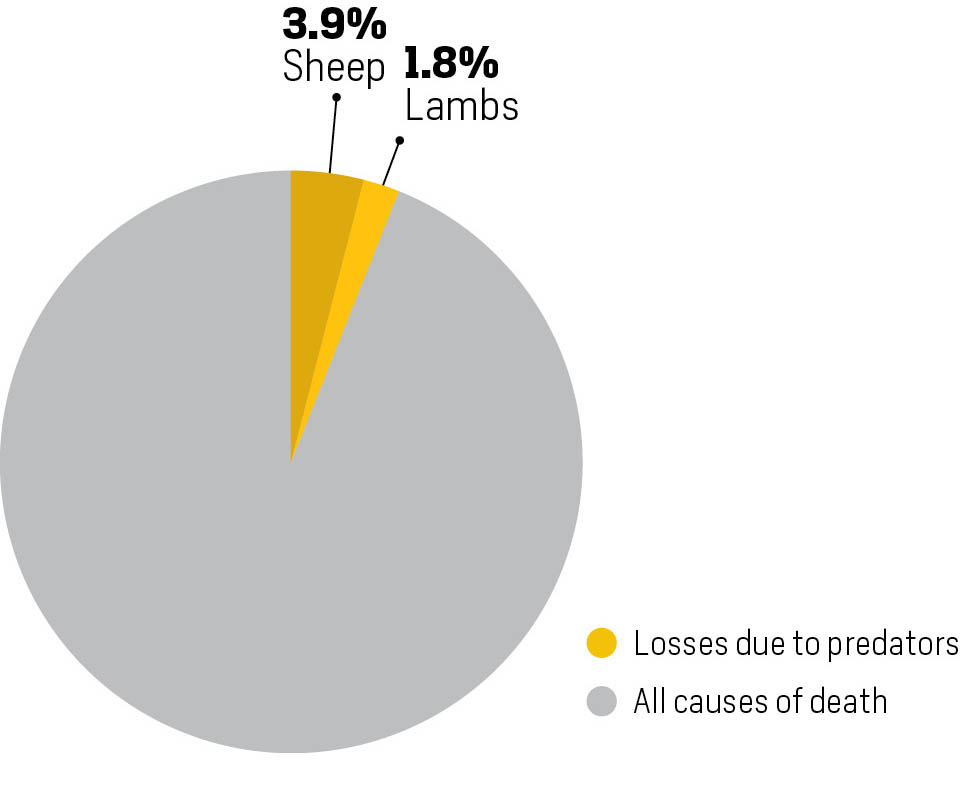

By far, most cattle and sheep are lost in ways that do not involve predators. Predation is responsible for 4 to 6 percent of all cattle and sheep deaths.

- 1.8% of adult sheep lost to predation

- 3.9% of lambs lost to predation

- 2.3% of adult cattle lost to predation

- 8% of calves lost to predation

Other causes of livestock losses include old age, lambing problems, disease, parasites, weather, accidents, poisoning, and theft.

Goat losses are significantly higher, at more than 30 percent of all deaths, a fact that certainly deserves more examination. Coyotes are the foremost predator of goats, as reported by many sources, although a USDA breakdown of predator-caused goat deaths isn’t available.

Overview of Predator Threats

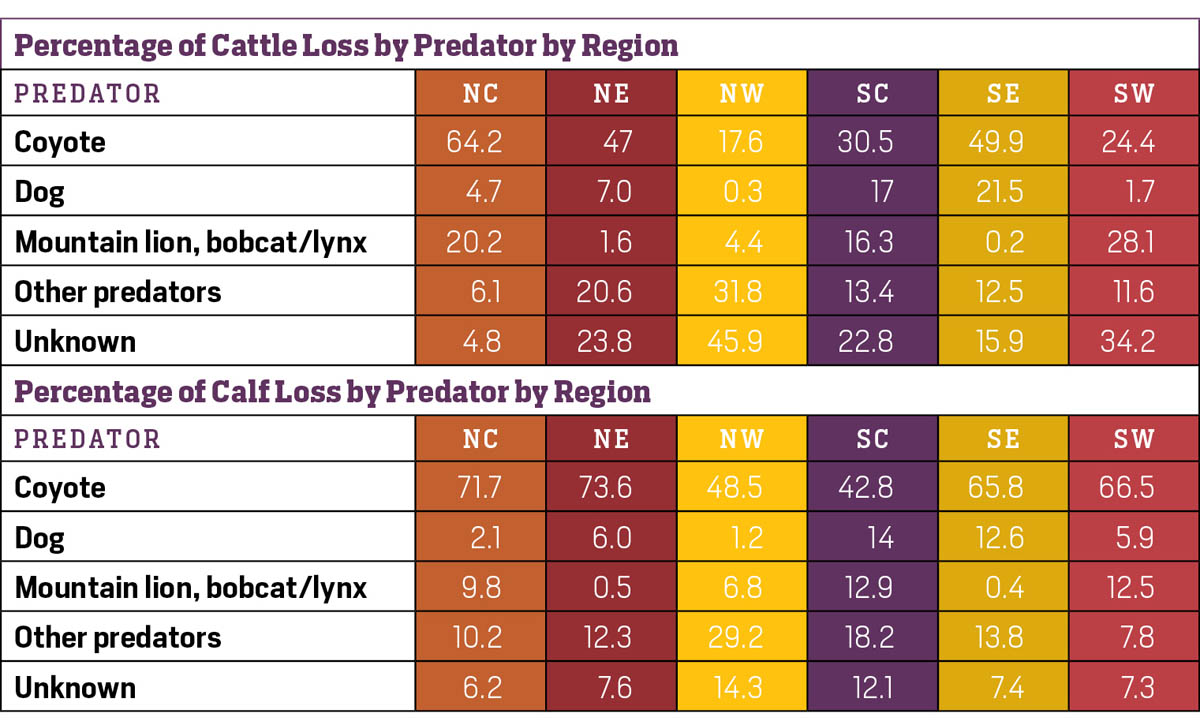

The USDA figures also show us how small and large operations differ and how the predator threats vary across regions of the country.

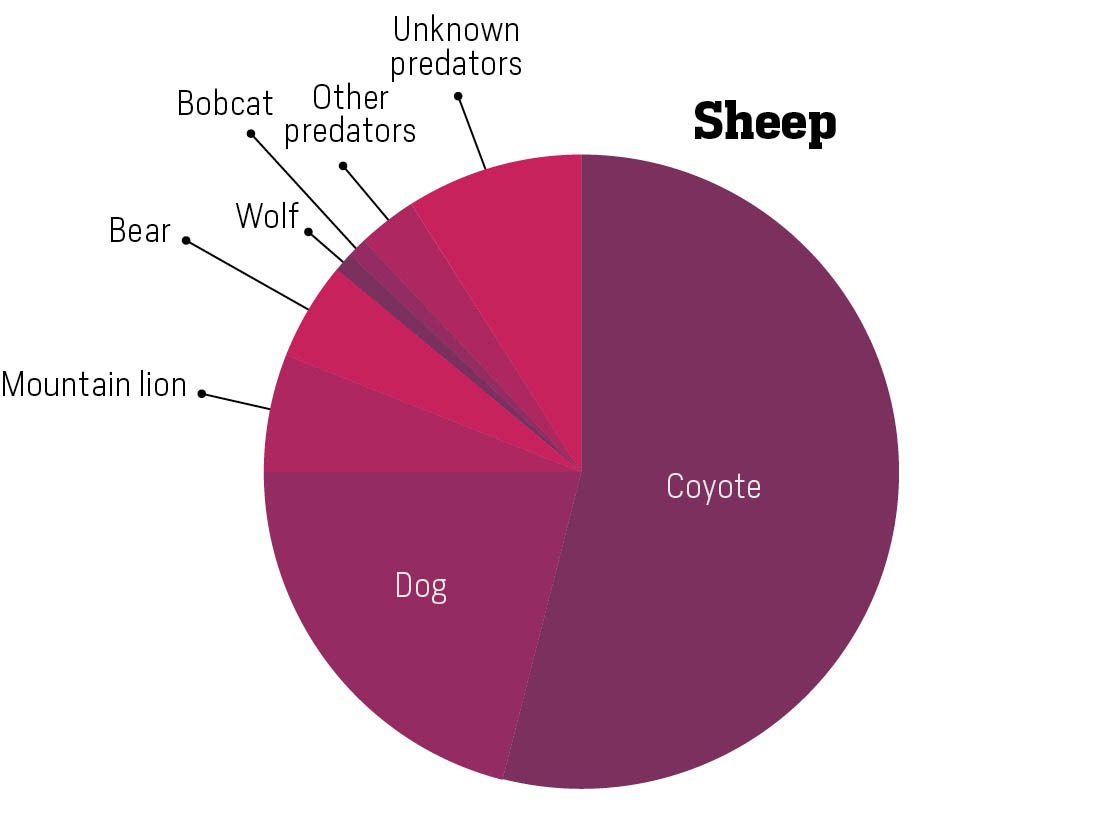

Sheep. In flocks with more than 25 animals, the coyote is the primary killer, while in smaller farm flocks, domestic dogs are the greatest threat. In pastured or range flocks larger than 1,000 sheep, coyotes remain the major predator by far, followed by mountain lions, bears, and wolves. Bears kill more sheep in Colorado, Utah, and Nevada. Dogs cause more deaths than coyotes do in New Mexico.

Cattle. In cattle herds, coyotes are responsible for about 60 percent of all predator losses, but small operations of less than 50 animals lose twice as many animals to predators than do larger operations. The southwestern states have the highest percentage of adult cattle loss to predators, followed by southeastern areas; and the Southeast has experienced the greatest increase in calf losses. The fact that coyotes have recently moved into the Southeast is no doubt very relevant to the situation.

Goats. Almost half of all the goats in the United States are raised in Texas. Across the country there are about 2 million meat goats and 0.5 million dairy and fiber goats. Predator losses are high, especially in the Southeast and Texas.

Intersection of Rural and Urban

Rural areas can vary from wilderness and open range to recreational and suburban use; however, dealing with predators is not just a rural problem by any measure. The altered landscape and the loss of the apex predators (wolves, mountain lions, and grizzly bears) opened the door to the other predators that have adapted and flourished — black bears, coyotes, bobcats, foxes, raccoons, and skunks. These predators have greatly expanded their ranges and numbers in recent decades.

Meanwhile, as housing and recreation have pushed into rural and undeveloped areas, large-predator threats are growing, from coyotes to the large cats, bears, and wolves. At this intersection of rural and suburban, on both small and hobby farms, we now see many such threats to small livestock, poultry, pets, and people. Predators are creeping into backyards and neighborhoods, attracted by bird feeding, garbage, rodents, and feral cats.

Predator |

Sheep |

Lamb |

Coyote |

54.3% |

63.7% |

Dog |

21.4% |

10.3% |

Mountain lion |

5.6% |

4.5% |

Bear |

5.0% |

3.0% |

Wolf |

1.3% |

0.4% |

Bobcat/lynx |

1.1% |

2.8% |

Other Predators |

Black vulture |

0.6% |

1.4% |

Fox |

0.5% |

1.9% |

Feral pig |

0.4% |

0.7% |

Eagle |

0.2% |

3.7% |

Other animals |

0.6% |

0.6% |

Unknown predator |

8.6% |

5.5% |

Assessing Your Predator Risks

As a first step, homeowners, farmers, and ranchers need to arm themselves with knowledge. Specific predator information relevant to your area can be found from the natural resource departments in states and provinces, the USDA extension offices, the Ministry of Agriculture in Canada, and livestock producers’ organizations. The USDA reports on death loss provide further specifics state by state. Stay informed on the current situation by talking to neighbors and following local news stories. Your observations are essential, not only to assess which predator is present but also to pinpoint the time of year and location on your property. Your observations need to be further informed by serious investigation of any predator attacks.

To evaluate your risk of a predator encounter or attack, consider the following:

- Predation statistics from the US National Agricultural Statistics Service or Canada’s Ministry of Agriculture, to determine most likely threats

- Predator identification in your local area, even at your specific farm or home

- Predator pressure changes during the year, including offspring needing food, and weather or season reducing access to prey animals

- Predator movements that are likely in the future as animals migrate into new areas

- Predator attractions, including your terrain, stock, and husbandry

Beware of the Dogs

Clearly, coyotes are the primary predator that livestock raisers face across the continent. In many areas, they are a relatively new threat. The startling revelation, however, is that domestic dogs kill the next-largest number of livestock. Dogs also cause the most emotional upset, because they slaughter animals viciously, in large numbers — and not primarily for food.

Removing free-roaming dogs, most of which are not feral, from the predation statistics would make these charts more accurately represent the threat that true wild predators pose for livestock.

As you analyze your particular situation, pay attention to the terrain as it relates to your husbandry practices.

- Heavily wooded, rough, or very large areas are riskiest for stock.

- Many predators are reluctant to cross large open areas.

- Grazing areas farther removed from human residence are more vulnerable.

- Land with a mosaic of fields and forests and areas with high deer population are attractive to predators.

- Unprotected hay or other crop storage will attract deer and elk, and their predators.

Predator Threat by Region

This detailed information from the USDA will help determine what is likely to be a threat in your region.

Was This an Attack?

Your own observations about predators on your property are essential. When you find a dead animal, you need to determine if it died from natural causes or a predator attack. In most cases animals and poultry die of natural causes rather than a predator attack. Your ability to determine the cause of death is partially determined by how rapidly you find the carcass before scavengers show up and begin to feed.

Try not to disturb the physical evidence of tracks, scat, blood on the ground, drag marks, disturbed vegetation, or a covered carcass. Take photographs, if possible, and record your observations. Wear gloves and protective clothing when examining a dead animal or afterbirth. In many cases, assistance from a veterinarian or wildlife damage expert can be valuable in determining natural causes of death versus a predator attack — especially if you are experiencing multiple deaths.

Questions to consider:

Can you determine the time the attack occurred?

Are there signs of a struggle? Signs may include torn wool, hair, or feathers; blood splatter; drag marks; and damaged vegetation.

How are your other animals behaving? Unusual or unsettled behavior may include nervousness, scattering, and increased vocalization.

Are there bite marks? If so, where are they located and what is their size? Take measurements and photographs to help you identify the predator. Try to identify whether it was a mammal or a raptor. You may need to clip hair or wool to look for puncture marks. When bites are made to a living animal, there will be bruising or hemorrhaging under the skin.

Is there significant blood? Profuse bleeding occurs before death and for a short time after. A death from natural causes, not an accident or attack, may show a loss of bodily fluids such as urine but not much blood.

Is the animal a newborn or a stillborn? Stillborn animals may have soft membranes covering the hooves. A field autopsy can also reveal important information. Pink lungs indicate the animal was breathing before death, while stillborn animals have dark-colored lungs that will not float in water. Milk in the stomach indicates the newborn was able to nurse before death.

Keeping an Eye Out

Trail cameras can help you determine which predators are nearby or threatening your stock, where they are testing or accessing your fences, and whether they have become habituated to other predator protection measures. The newer trail cameras have better resolution, increased memory, and better battery life than older models.

Nighttime flash can be infrared or LED. Other features to consider include the time delay or trigger speed between the motion sensor detecting an animal and the shutter being engaged, and the speed of consecutive photos. Sturdy cases can be very important if predators, especially bears, might investigate the cameras.

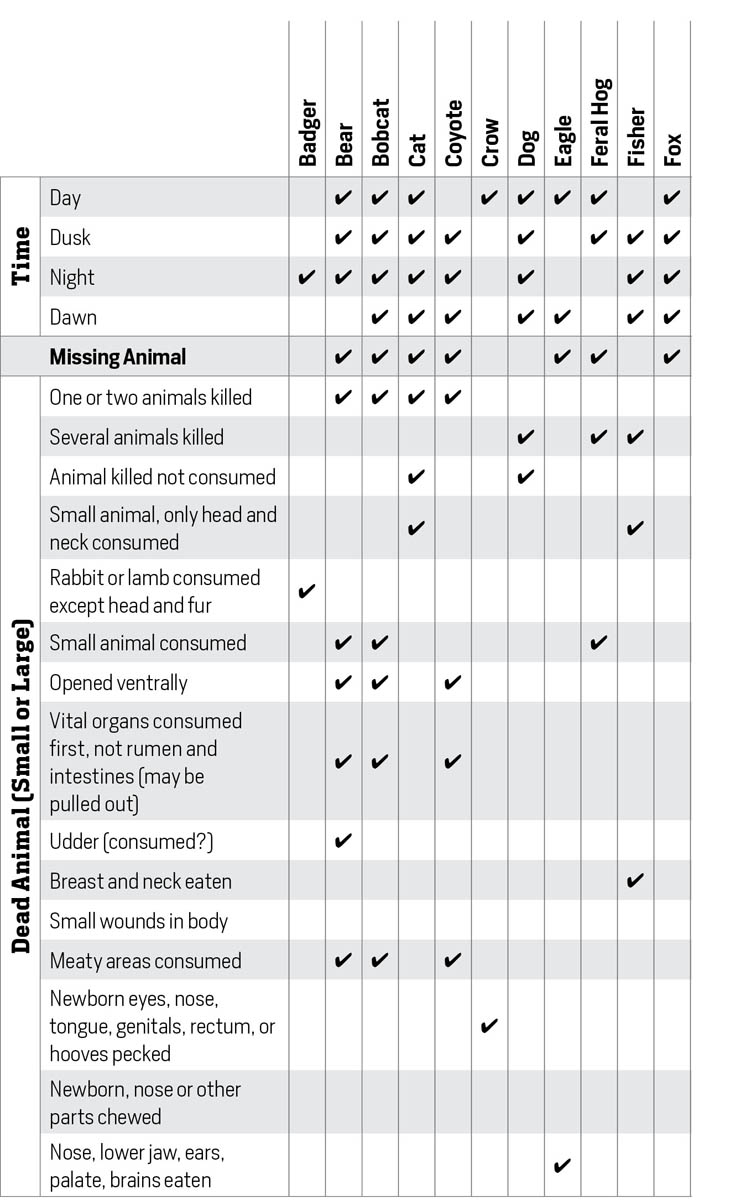

Poultry Damage ID Guide — Common Predators

After identifying potential culprits below, check individual profiles in Part II for additional details, observations, tracks, and scat.

Note: Predators can occasionally be active during nonnormal times or behave in atypical ways.

The charts below may be hard to read. Double-tap the charts to open to fill the screen. Use the two-finger pinch-out method to zoom in. (These features are available on most e-readers.)

|

Other Observations

|

|

Event

|

Cause

|

|

Animal(s) killed and mauled but not eaten

|

Dog

|

|

Bites on legs of live birds

|

Rat

|

|

Dead chicks or birds stuck in tunnels

|

Rat

|

|

Musky smell

|

Skunk, weasel, mink

|

|

Feathers on ground

|

Fox, coyote, hawk, owl

|

|

Wounds or pulled feathers on back and tail of live bird

|

Cannibalization

|

|

Injuries on back, pulled feathers

|

Rooster mounting hen

|

|

Several dead birds piled against fence or in corners, carcasses flattened

|

Fright and panic due to chasing by dogs, wolves, or other larger predators

|

|

Serious damage to coop

|

Bear

|

|

Latches opened

|

Raccoon, human

|

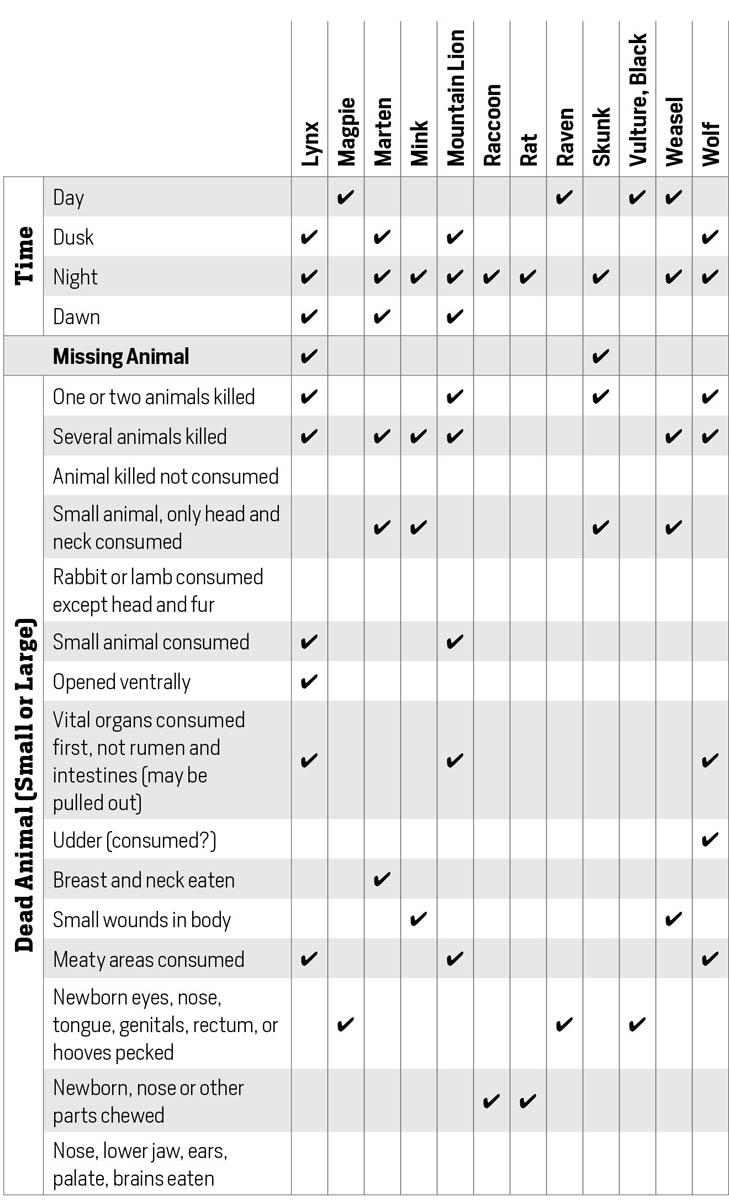

Livestock Damage ID Guide — Likely Suspects

After identifying potential culprits below, check individual profiles in Part II for detailed information, observations, tracks, and scat. Small predators can kill, carry away, or consume only very small livestock — rabbits or small lambs, for example. Predators can occasionally be active during nonnormal times or behave in atypical ways.