IN RECENT YEARS, organizations of all shapes and sizes have begun to embrace design methodologies. People sometimes ask me if this surprises me; and the truth is, not really.

Over the years I’ve had a front-row seat to watch as technology got better and better. In my days at the MIT Media Lab, again and again, Moore’s Law played out before my eyes, as computational systems and networks got faster and faster, cheaper and cheaper. As this continued, we were all told that products and services were going to keep getting better and better; but I just didn’t see that happening. At some point, it became clear to me that technology alone was not going to make products and services any better.

This is when design began to emerge as ‘the way to make a difference’. Not just in products and services, but in addressing questions of how to solve the world’s problems and how to run your organization better as well – to figure out how to combat complexity and to create new value.

The march of technology is definitely tied to the emergence of design. One of the reasons organizations are so chaotic today is because of social media, itself a new technology. A significant side effect of the digital communications revolution is that nowadays, everyone can have a voice. Just a few years ago, front-line workers would never see the CEO or expect to talk to them; but nowadays you can e-mail your CEO – and you sort of expect him or her to write you back! You can even friend him on Facebook.

What this has done is to transform organizations from hierarchies into more of a ‘heterarchy’, where everyone gets to have a say. Make no mistake about it: this represents a major shift for leaders, who are going to have to evolve – and fast! And this is where the radical aspect of design – the ability to rethink things – comes into play. On the one hand, design can still help us create differently-shaped products featuring imaginative solutions; but on the other – and more importantly – design can enable organizations to run better and adapt to changing conditions.

Part of my own function now is to sit on different boards – to function as ‘the person who understands design’ at that level. This makes me optimistic that one day in the not-too-distant future, design will be as much a part of every organization as marketing, accounting or finance. That being said, the fact is, some things don’t need design. There are things that just kind of work already – that have evolved over centuries.

My hope is not that design will be everywhere, but that design will be where it is most needed, which is in creating new kinds of experiences and products, and addressing the challenges organizations are facing as they move from hierarchichal to heterarchichal entities. And from what I have seen, design is up to the task.

John Maeda is president of the Rhode Island School of Design and author of Redesigning Leadership (Design, Technology, Business, Life) (MIT Press, 2011) and The Laws of Simplicity (Design, Technology, Business, Life) (MIT Press, 2006).

of Business

We are on the cusp of a design revolution

in business, and as a result, business people

don’t just need to understand designers

better – they need to become designers.

By

THESE ARE TURBULENT TIMES FOR BUSINESS, as companies struggle to adjust to the globalization of markets and competition, the expansion of the service-based economy, the impact of deregulation and privatization, and the explosion of the knowledge revolution. All of these forces are driving firms to fundamentally rethink their business models and radically transform their capabilities – but an equally important (though less obvious) business transformation is taking place with respect to design.

As we leave behind one economic age and enter another, many of our philosophical assumptions about what constituted competitive success grew out of a different world. Value creation in the 20th century was largely defined by the conversion of heuristics to algorithms. It was about taking a fundamental understanding of a ‘mystery’ – a heuristic – and driving it to a formula, an algorithm – so that it could be driven to huge scale and scope. As a result, many 20th-century organizations succeeded by instituting fairly linear improvements, such as reengineering, supply chain management, enhanced customer responsiveness, and cost controls. These ideas were consistent with the traditional Taylorist view of the company as a centrally-driven entity that creates wealth by getting better and better at doing the same thing.

Competition is no longer in global scale-intensive industries; rather, it’s in non-traditional, imagination-intensive industries. Today’s businesses are sensing an increased demand for speed in product development, design cycles, inventory turns, and competitive response, and there are major implications for the individuals within those organizations. I would argue that in the 21st century, value creation will be defined more by the conversion of mysteries to heuristics – and that as a result, we are on the cusp of a design revolution in business.

Over the course of time, phenomena enter our collective consciousness as mysteries – things that we observe, but don’t really understand. For instance, the mystery of gravity once confounded our forefathers: when they looked around the world, they saw that many things, like rocks, seemed to fall to the ground almost immediately; but others didn’t – like birds, and some seemed to take forever, like leaves. In art, there was the long battle to understand how to represent on a two-dimensional page what we saw in front of us in three dimensions. Music continues to be a mystery that confounds: what patterns of notes and sounds are enjoyable and make listeners feel happy and contented?

We start out with these mysteries, and at some point, we put enough thought into them to produce a first-level understanding of the question at hand. We develop heuristics – ways of understanding the general principles of heretofore mysteries. Heuristics are rules of thumb or sets of guidelines for solving a mystery by organized exploration of the possibilities.

So why do things fall down? We develop a notion of a universal force called ‘gravity’ that tends to pull things down. In art, we develop a notion called ‘perspective’ that guides our efforts to create renderings that appear to the eye to have three-dimensions rather than two. What kind of music do people like to listen to? We learn about chords, and then create song types like ballads, or folk songs, or the blues. If one follows a set of guidelines, one will likely create something that people enjoy listening to.

Heuristics don’t guarantee success – they simply increase the probability of getting to a successful outcome. They represent an incomplete understanding of a heretofore mystery. In any given field, some people barely understand heuristics, while others master them. The difference between them is the difference between one-hit-wonder Don McLean, author of “American Pie”, and Bruce Springsteen, author of scores of hit songs. For McLean, the mystery remained just that: he came up with a single inspiration that created one random event – one of the biggest pop song hits of all time. Yet he failed to produce another hit of any consequence in his entire musical career. In contrast, Springsteen developed a heuristic – a way of understanding the world and the people in it – that enables him to write songs that have great meaning to people and are immensely popular. His mastery of heuristics has allowed him to generate a steady stream of hit albums/CDs over a 30-year period.

In due course, increasing understanding can (though in many cases it never does) produce an algorithm: a logical, arithmetic or computational procedure that, if correctly applied, ensures the solution of the problem. With gravity, great scientists like Sir Isaac Newton studied and experimented long and hard enough to create precise rules for determining how fast an object will fall under any circumstance. In the late 1970s, musical innovators like British techno-music guru Brian Eno experimented with the human heartbeat and determined that songs with a synthesized heartbeat as their rhythm track are instinctively enjoyed by listeners, no matter what you added on top of them. The end result of such algorithms is not always positive, of course: this discovery led to electro-pop and eventually to sham bands like Milli Vanilli, who lip-synched recorded music onstage until caught in the act by an unsuspecting audience. And in art, we eventually got paint by numbers.

In the modern era, a fourth important step has been added to the sequence of mystery to heuristic to algorithm. Eventually, some algorithms now get coded into software. This means reducing the algorithm – the strict set of rules – into a series of 0’s and 1’s – binary code – that enables a computer to produce a result. For example, with gravity, the fact that we had an algorithm for how things fall meant that we could program aircraft with autopilot, enabling a plane to ‘fall’ from the sky in the organized fashion that we want it to, so that it lands in exactly the right spot. At the coding level, there is no longer any judgment involved: the plane lands on the basis of computer instructions that are nothing but a series of 1’s and 0’s, because our understanding of gravity has moved from a mystery to a heuristic to an algorithm to binary code.

The progression of the ‘march of understanding’ described herein has important practical implications for today’s business people. Broadly speaking, value creation in the 20th century was about taking a fundamental understanding of a mystery – a heuristic – and reducing it to a formula, an algorithm – so that it could be driven to huge scale and scope.

Take McDonalds, for instance. In 1955, the McDonald brothers took a mystery – ‘how and what do Californians want to eat’? And they created a format for answering that – a heuristic – which was the quick-service restaurant. Is this heuristic what created enormous value? No, because there were many restaurants in California doing similar things at the time, and all of them were discovering that Californians wanted faster, more convenient food. What made McDonalds different is that Ray Kroc came along and saw that he could drive the McDonald brothers’ heuristic to an algorithm. He bought the store and figured out exactly how to cook a hamburger, exactly how to hire people, exactly how to set up stores, exactly how to manage stores, and exactly how to franchise stores. Under Kroc, nothing was left to chance in the McDonald’s kitchen: every hamburger came out of a stamping machine weighing exactly 1.6 ounces, its thickness measured to the thousandth of an inch, and the cooking process stopped automatically after 38 seconds, when the burgers reached an internal temperature of exactly 155 degrees. By creating an algorithm out of a heuristic, Kroc was able to drive McDonalds to huge size and scope, and to its place today as a global icon.

This move from heuristic to algorithm was repeated over and over throughout the 20th century. Early in the century, Ford developed the algorithm for assembling cars – the assembly line – and with it grew to immense size. Late in the 20th century, Electronic Data Services (EDS) developed algorithms for routinizing systems integration and training COBOL programmers, and with it grew to previously unimagined size in the systems integration business. In between, Procter & Gamble created the algorithm for brand management, Anheuser Busch for making and selling beer, Frito Lay for making and distributing snack chips, and so on. For these companies, as well as Dell and Walmart, success depended not so much on a superior product, but on a superior process, and each is an example of the relentless ‘algorithm-ization’ that paved the way for massive value creation in the 20th century.

This dynamic accelerated in the latter part of the 20th century (1985-2000), when many algorithms were driven to code. Like most things in life, this final step of reducing something to binary code has good and not-so-good aspects to it. While coding enables an incredible increase in efficiency, it is also true that with coding comes the end of judgment: patterns of 0’s and 1’s have no judgment or artistry – they just automatically apply an algorithm. In many respects, the extreme achievement of the 20th century is soulless numbers. Neither all bad or all good, this is simply the result of the combination of the relentless march of understanding (from mystery to heuristic to algorithm) with the relentless march of Moore’s Law (Intel co-founder Gordon Moore’s prediction that data density would double approximately every 18 months, and the resultant diminishing costs of information technology) – all of which lead to binary code.

So where do we go from here? Will there be more relentless algorithm-ization? I don’t think so. I believe that we will look back on the 20th century as a tour de force of producing ‘stuff’ – lots of it, as efficiently as possible. I believe we are transitioning into a 21st century world in which value creation is moving back to the world of taking mysteries and turning them into heuristics. I see the beginnings of a fundamental backlash against algorithmization and the codification of the world around us – a realization that reaching to grab the benefits of economies of scale often involves accepting standardization and soullessness in exchange.

I believe the 21st century will go down in history as the century of producing elegant, refined products and services – products and services that delight users with the gracefulness of their utility and output; ‘goods’ that are produced elegantly – for example, that have the most minimal environmental footprint possible, or that produce the fewest worker injuries, whether it be broken limbs or repetitive stress syndrome.

The 21st century presents us with an opportunity to delve into mysteries and come up with new heuristics. As a society we are faced with major mysteries like, ‘how can big cities actually work’? There are more of them than ever before, and while Toronto works pretty well, many cities around the world don’t, and fixing that is a major mystery. Another big mystery involves how to make health care work, when there’s an infinite demand and a constrained supply. These are the kind of modern mysteries that are being presented to us, and there is no algorithm for them, no coding to magically solve the problems they engender.

There are three major implications of this shift for today’s business people. The first is that design skills and business skills are converging. The skill of design, at its core, is the ability to reach into the mystery of some seemingly intractable problem – whether it’s a problem of product design, architectural design, or systems design – and apply the creativity, innovation and mastery necessary to convert the mystery to a heuristic – a way of knowing and understanding.

But unlike in the 20th century, this time the goal won’t be to develop mass formulas or algorithms. Firms today are desperately trying to find out what each individual customer wants. Kellogg’s cereal and Hershey’s chocolate bars have 1-800 phone numbers printed on them encouraging consumers to call them with feedback. Pepsi has its Web site printed on each can. Information is being gathered and used to cater to and customize solutions to your every need.

I would argue that to be successful in the future, business people will have to become more like designers – more ‘masters of heuristics’ than ‘managers of algorithms’. For much of the 20th century, they moved ahead by demonstrating the latter capability. This shift creates a huge challenge, as it will require entirely new kinds of education and training, since until now, design skills have not been explicitly valued in business. The truth is, highly-skilled designers are currently leading many of the world’s top organizations – they just don’t know they are designers, because they were never trained as such.

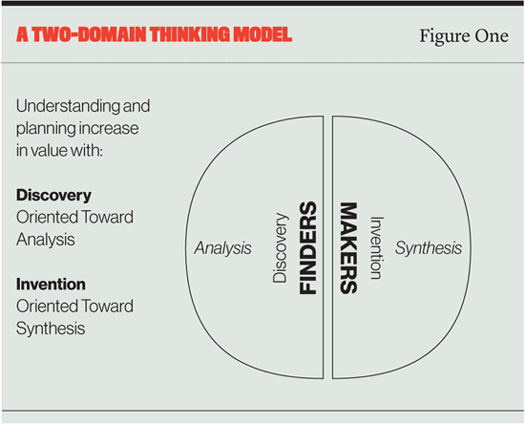

The second implication is that we need a new kind of business enterprise. This new world into which we are delving will require us to tackle mysteries and develop heuristics – and that will require a substantial change in some of the fundamental ways we work. Traditional firms will have to start looking much more like design shops on a number of important dimensions, as shown in Figure One.

MODERN FIRMS MUST BECOME MORE LIKE DESIGN SHOPS |

Figure One |

|

Feature |

From ‘Traditional Firm’ |

To ‘Design shop’ |

Flow of Work life |

• Ongoing tasks • Permanent assignments |

• Projects • Defined terms |

Source of status |

Managing big budgets and large staffs |

• Solving ‘wicked problems’ |

Style of Work |

• Defined roles • Wait until it is “right” |

• Collaborative |

Mode of Thinking |

• Deductive |

• Deductive |

Dominant attitude |

• We can only do what we have budget to do • Constraints are the enemy |

• Nothing can’t be done • Constraints increase the challenge and excitement |

Whereas traditional firms organize around ongoing tasks and permanent assignments, in design shops, work flows around projects with defined terms. The source of status in traditional firms is ‘managing big budgets and large staffs’, but in design shops, it derives from building a track record of finding solutions to ‘wicked problems’ – solving tough mysteries with elegant solutions. Whereas the style of work in traditional firms involves defined roles and waiting for the perfect answer, design firms feature extensive collaboration, focused brainstorming sessions, and constant dialogue with clients.

When it comes to innovation, businesses have much to learn from designers. The philosophy in design shops is, ‘let’s try it, prototype it, and improve it’. Designers learn by doing. The style of thinking in traditional firms is largely inductive – proving that something actually operates – and deductive – proving that something must be. Design shops add abductive reasoning to the fray – which involves suggesting that something may be, and reaching out to it. Designers may not be able to prove that something is or must be, but they nevertheless reason that it may be, and this style of thinking is critical to the creative process. Whereas the dominant attitude in traditional firms is to see constraints as the enemy and budgets as the drivers of decisions, in design firms, the mindset is “nothing can’t be done for sure,” and constraints only increase the excitement level.

The third implication is that we must change the focus of our thinking on design and business. The trends discussed herein have generated increased interest in design by the business world, but it is largely focused on ‘the business of design’: the traditional business world is trying to figure out what designers do, how they do it, and how best to manage them. This misses the point fundamentally, and it won’t save the traditional firm. The focus should actually be placed on ‘the design of business’: We need to think much more about designing our businesses to provide elegant products and services in the most graceful manner possible.

Business people don’t need to understand designers better: they need to be designers. They need to think and work like designers, have attitudes like designers, and learn to evaluate each other as designers do. Most companies’ top managers will tell you that they have spent the bulk of their time over the last decade on improvement. But it’s no longer enough to get better; you have to ‘get different’.

I believe that we are on the cusp of a design revolution in business – a revolution in the purpose of business, the work of business, and the skills required of business people. The challenge of making the transformation to the Design of Business should not be underestimated. The initial goal is to help modern managers understand this new business agenda and become shapers of contexts, to increase the likelihood that their organizations will thrive in the era of design.

Roger Martin is Dean, Premier’s Research Chair in Productivity & Competitiveness and Professor of Strategic Management at the Rotman School of Management. He is the author of eight books, most recently, Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works (Harvard Business Review Press, 2013), co-authored with A.G. Lafley. In 2011, he placed sixth on the Thinkers50 list, a bi-annual ranking of the most influential global management thinkers.

Today’s leaders can apply many of the lessons learned in the world of design to strategy-making in the workplace.

By

AS WE STAND AT THE FRONTIER OF A BUSINESS WORLD in the midst of fundamental change, the field of business strategy is in need of new metaphors. Much of the traditional thinking about strategy formulation and implementation seems ill-suited to escalating imperatives for speed and flexibility. We need metaphors that better capture the challenges of making strategies both real and realizable, metaphors that bring life to the human dimension of creating new futures for institutions, that move us beyond the sterility of traditional approaches to strategic planning. In that spirit, I propose that we resuscitate an old metaphor that I believe offers new possibilities: the metaphor of strategy as a process of design.

The centrality of design skills to the practice of management has long been recognized. In 1969, Nobel Laureate Herbert Simon noted:

“Engineering, medicine, business, architecture, and painting are concerned not with the necessary but with the contingent – not with how things are, but with how they might be – in short, with design. Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones. Design, so construed, is the core of all professional training.”

Early models of the design process describe it as consisting of two phases: analysis and synthesis. In the analytical phase, the problem is decomposed into a hierarchy of problem subsets, which in turn produce a set of requirements. In the ensuing stage of synthesis, these individual requirements are grouped and realized in a complete design. Parallels with the design of business planning processes come to mind here. Unlike in business, however, these early models – with their emphasis on systematic procedures – met with immediate criticism for their lack of appreciation for the complexity of design problems.

Design theorist Horst Rittel first called attention to what he described as the ‘wicked’ nature of design problems. Such problems have a unique set of properties, he argued, the most important of which is that they have no definitive formulation or solution. The definition of the problem itself is open to multiple interpretations, dependent upon the worldview of the observer, and potential solutions are many, with none of them able to be proven to be correct. Writers in the field of business have argued that many issues in strategy formulation are ‘wicked’ as well, and that traditional approaches to dealing with them are similarly incapable of producing intelligent solutions.

The ‘first generation models’, as Rittel referred to them, were ill-suited for dealing with ‘wicked problems’. Rittel saw design as a process of argumentation, rather than merely analysis and synthesis. Through argumentation – whether as part of a group or solely within the designer’s own mind – the designer gained insights, broadened his or her worldview, and continually refined the definition of the problem and its attendant solution. Thus, the design process came to be seen as one of negotiation rather than optimization, fundamentally concerned with learning and the search for emergent opportunities. Rittel’s arguments are consistent with recent calls in the strategy literature for more attention to ‘strategic conversations’, in which a broad group of organizational stakeholders engage in dialogue-based planning processes out of which shared understanding and ultimately, shared choices, emerge.

Studies of the design process frequently suggest a hypothesis-driven approach similar to the traditional scientific method. After studying architects in action, philosopher and academic Donald Schon described design as “a shaping process,” in which the situation “talks back” continually, and “each move is a local experiment which contributes to the global experiment of reframing the problem.” Schon’s designer begins by generating a series of creative “what if” hypotheses, selecting the most promising one for further inquiry. This inquiry takes the form of a more evaluative “if then” sequence, in which the logical implications of that particular hypothesis are more fully explored and tested. The scientific method then, with its emphasis on cycles of hypothesis-generating and testing and the acquisition of new information to continually open up new possibilities, remains central to design thinking.

Yet the nature of ‘wicked problems’ makes such trial and error learning problematic. Rittel makes this point from the perspective of architecture: a building, once constructed, cannot be easily changed, and so learning through experimentation in practice is undesirable. This is the ultimate source of ‘wickedness’ in such problems: their indeterminacy places a premium on experimentation, while the high cost of change makes such experimentation problematic.

As in business, we know that we might be able or be forced to change our strategies as we go along – but we’d rather not. This apparent paradox is what gives the design process – with its use of constructive forethought – its utility. The designer substitutes mental experiments for physical ones. In this view, design becomes a process of hypothesis-generating and testing, whose aim is to provide the builder with a plan that tries to anticipate the general nature of impending changes.

A concern of the design process is the risk of ‘entrapment’, in which a designer’s investment in early hypotheses make them difficult to give up as the design progresses, despite the presence of disconfirming data. Design is most successful, then, when it creates a virtual world, a ‘learning laboratory’, where mental experiments can be conducted risk-free and where investments in early choices can be minimized.

This, I argue, offers a very different perspective from which to think about the creation of business strategies. Traditional approaches have shared the perspective of early design theorists and assumed that planning creates value primarily through a process of controlling, integrating, and coordinating – that the power of planning is in the creation of a systematic approach to problem-solving – decomposing a complex problem into subproblems to be solved and later integrated back into a whole. While integration, coordination, and control are all potentially important tasks, a focus on these dramatically underestimates the value of planning in a time of change. The metaphor of design calls attention to planning’s ability to create a virtual world in which hypotheses can be generated and tested in low-cost ways.

Contemporary design theorists have been attentive to the areas in which design and science diverge, as well as converge. The most fundamental difference between the two, they argue, is that design thinking deals primarily with what does not yet exist; while scientists deal with explaining what is. That scientists discover the laws that govern today’s reality, while designers invent a different future, is a common theme. Thus, while both methods of thinking are hypothesis-driven, the design hypothesis differs from the scientific hypothesis.

Rather than using traditional reasoning modes of induction or deduction, Stanford’s James March argues that design thinking is abductive: “Science investigates extant forms. Design initiates novel forms. A scientific hypothesis is not the same thing as a design hypothesis…A speculative design cannot be determined logically, because the mode of reasoning involved is essentially abductive.”

Underlying this emphasis on conjectural thinking and visualization is an ongoing inquiry into the relationship between verbal and non-verbal mediums. Design theorists accord a major role to the use of graphic and spatial modeling media – not merely for the purpose of communicating design ideas, but for the generation of ideas as well. “Designers think with their pencils” is a common refrain. Gestalt psychologist Rudolf Arnheim asserts that the image “unfolds” in the mind of the designer as the design process progresses. And that it is, in fact, the unfolding nature of the image that makes creative design possible. The designer begins with what Arnheim calls “a centre, an axis, a direction,” from which the design takes on increasing levels of detail as it unfolds.

In addition to the prominent role played by conjecture and experimentation in design thinking, there is also a fundamental divergence between the concern of science for generalizable laws and design’s interest in the particulars of individual cases.

This quality of indeterminacy has profound implications for the design process. First, the tendency to project determinacy onto past choices – ‘prediction after the fact’ – is ever-present and must be avoided, or it undermines and distorts the true nature of the design process.

Secondly, creative designs do not passively await discovery; designers must actively seek them out. Third, the indeterminacy of the process suggests the possibility for both exceptional diversity and continual evolution in the outcomes produced (even within similar processes). And finally, because design solutions are always matters of invented choice, rather than discovered truth, the judgement of designers is always open to question by the broader public.

Each of these implications resonates with business experiences. The need to seek out the future is one of the most common prescriptions in today’s writings on strategy. The risks that the search for the ideal of ‘the one right strategy’ can stifle creativity, cause myopia, and paralyze organizational decision processes have all been recognized.

Yet, the final implication – this notion of the inevitable need to justify to others the ‘rightness’ of the design choices made – is perhaps the most significant implication for the design of strategy processes in business organizations. Because strategic choices can never be proven to be ‘right’, they remain always contestable and must be made compelling to others in order to be realized. This calls into play Rittel’s role of argumentation and focuses attention on others, and the role of rhetoric in bringing them into the design conversation. Participation becomes key to producing a collective learning that both educates individuals and shapes the evolving choices simultaneously. Thus, design becomes a shared process – no longer the province of a single designer.

Participation is critical, in part, because of the role that values, both individual and institutional, play in the design process. Values drive both the creation of the design and its acceptance. Successful designs must embody both existing and new values simultaneously. The ability to work with competing interests and values is inevitable in the process of designing.

The ‘charette’ plays a fundamental role in making design processes participative and making collective learning possible. Charettes are intensive brainstorming/planning sessions in which groups of stakeholders come together. Their intention is to share, critique, and invent in a way that accelerates the development of large-scale projects. One well-known user of charettes is the architectural firm Duany, Plater-Zyberk, who specialize in the design of new ‘traditional towns’ like Seaside, Florida, or Disney’s Celebration. In their charette for the design of a new town outside of Washington, D.C., they brought together architects, builders, engineers, local officials, traffic consultants, utility company representatives, computer experts, architecture professors, shopping mall developers, and townspeople for a discussion that lasted seven days. The more complex the design process, the more critical role the charette plays – and I believe it offers a new model for planning processes in business.

Despite the avowed plurality that design theorists describe in their attempts to define the field, a set of commonalties does emerge from their work about the attributes of design thinking.

First, design thinking is synthetic. Out of the often-disparate demands presented by sub-units’ requirements, a coherent overall design must emerge. The process through which and the order in which the overall design and its sub-unit designs unfold remains a source of debate. What is clear is that the order in which they are given attention matters, as it determines the ‘givens’ of subsequent designs, but ultimately successful designs can be expected to exhibit considerable diversity in their specifics.

Secondly, design thinking is abductive in nature. It is primarily concerned with the process of visualizing what might be, some desired future state, and creating a blueprint for realizing that intention.

Third, design thinking is hypothesis-driven. Primary is the design hypothesis, which is conjectural and, as such, cannot be tested directly. Embedded in the selection of a particular promising design hypotheses, however, are a series of assumptions about a set of cause-effect relationships in today’s environment that will support a set of actions aimed at transforming a situation from its current reality to its desired future state. These explanatory hypotheses must be identified and tested directly. Cycles of hypothesis generation and testing are iterative. As successive loops of “what if” and “if then” questions are explored, the hypotheses become more sophisticated and the design unfolds.

Fourth, design thinking is opportunistic. As the above cycles iterate, the designer seeks new and emergent possibilities. It is in the translation from the abstract/global to the particular/local that unforeseen opportunities are most likely to emerge. Sketching and modeling are important tools in the unfolding process.

Fifth, design thinking is dialectical. The designer lives at the intersection of often-conflicting demands – recognizing the constraints of today’s materials and the uncertainties that cannot be defined away, while envisioning tomorrow’s possibilities.

Finally, design thinking is inquiring and value-driven – open to scrutiny, willing to make its reasoning explicit to a broader audience, and cognizant of the values embedded within the conversation. It recognizes the primacy of the Weltanschauung of its audience. While the architect imbues the design with his or her own values, successful designs educate and persuade by connecting with the values of the audience, as well.

Having developed a clearer sense of the process of design itself, we can now see the possibilities that such a metaphor might hold for thinking about business strategy, in general, and the design of strategy-making processes, in particular.

1. Like design, strategic thinking is synthetic. It seeks internal alignment and understands interdependencies. It is systemic in its focus. It requires the ability to understand and integrate across levels, both horizontal and vertical, and to align strategies across those levels. A strategic thinker has a mental model of the complete end-to-end system of value creation, and understands the interdependencies within it. The synthesizing process creates value not only in aligning the components, but also in creatively re-arranging them. The creative solutions produced by many of today’s entrepreneurs often rest more with the redesign of aspects of traditional strategies in ways that create added value for customers, rather than with dramatic breakthroughs.

2. Strategic thinking is abductive. It is future-focussed and inventive, providing the focus that allows individuals within an organization to leverage their energy, to focus attention, and to concentrate for as long as it takes to achieve a goal. The creation of a compelling intent relies heavily on the skill of alternative generation. Alternative generation has received far less attention in the strategic decision making literature than has alternative evaluation, but it is far more important in an environment of change.

3. Strategic thinking is hypothesis-driven. In an environment of ever-increasing information availability and decreasing time to think, the ability to develop good hypotheses and test them effectively is critical. Strategic thinking is both creative and critical in nature, and figuring out how to accomplish both types of thinking simultaneously has long troubled cognitive psychologists, since it is necessary to suspend critical judgment in order to think more creatively. Strategic thinking accommodates both creative and analytical thinking sequentially in its use of iterative cycles of hypothesis generating and testing. Hypothesis generation asks the question “what if...?”, while hypothesis testing follows with the critical question “if..., then...?” and brings relevant data to bear on the analysis. Taken together, and repeated over time, this sequence allows us to generate ever-improving hypotheses, without forfeiting the ability to explore new ideas. Such experimentation allows an organization to move beyond simplistic notions of cause and effect to provides ongoing learning.

4. Strategic thinking is opportunistic. Within this intent-driven focus, there must be room for opportunism that not only furthers intended strategy but that also leaves open the possibility of new strategies emerging. This requires that an organization be capable of practicing ‘intelligent opportunism’ at lower levels.

5. Strategic thinking is dialectical. In the process of inventing the image of the future, the strategist must mediate the tension between constraint, contingency, and possibility. The underlying emphasis of strategic intent is stretch – to reach explicitly for potentially unattainable goals. At the same time, all elements of the firm’s environment are not shapeable, and those constraints that are real must be acknowledged in designing strategy.

6. Strategic thinking is inquiring and, inevitably, value-driven. Because any particular strategy is invented, rather than discovered, it is contestable and reflective of the values of those making the choice. Its acceptance requires both connection with and movement beyond the existing mindset and value system of the rest of the organization, which relies on inviting the broader community into the strategic conversation. It is through participation in this dialogue that the strategy itself unfolds, both in the mind of the strategist and in that of the larger community that must come together to make the strategy happen.

What would we do differently in organizations today, if we took the design metaphor seriously? A lot, I believe.

The problems with traditional approaches to planning have long been recognized. They include the attempt to make a ‘science’ of planning, with its subsequent loss of creativity; the excessive emphasis on numbers; the drive for administrative efficiency at the expense of substance; and the dominance of single techniques, inappropriately applied. Yet, decades later, strategists continue to struggle to propose clear alternatives to traditional processes.

Design offers a different approach and suggests processes that are more widely participative, more dialogue-based, issue-rather-than-calendar-driven, conflict using rather than conflict avoiding, all aimed at invention and learning, rather than control.

If we were to take design’s lead, we would involve more members of the organization in two-way strategic conversations. We would view the process as one of iteration and experimentation, and pay sequential attention to idea generation and evaluation in a way that attends first to possibilities before moving onto constraints. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we would recognize that good designs succeed by persuading, and great designs by inspiring.

Jeanne Liedtka is the United Technologies Corporation Professor of Business Administration at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business and the former chief learning officer at United Technologies. She is the author of three books, most recently Solving Problems with Design Thinking: Ten Stories of What Works (Columbia University Press, 2013). This article was originally published in California Management Review.

Design has been proclaimed the ‘secret weapon’ for competition in the 21st century. Here’s how today’s managers can start thinking more like designers.

by Jeanne Liedtka

|

|

|

1. |

|

2. |

Jorn Utzon |

|

Frank Gehry |

|

|

|

3. |

|

4. |

Coco Chanel |

|

Golden Gate |

|

|

|

5. |

|

6. |

Pablo Picasso |

|

Ingvar Kamprad |

|

|

|

7. |

|

8. |

New Urbanism |

|

New Urbanism |

|

|

|

9. |

|

10. |

Thomas Jefferson |

|

Antoni Gaudi |

THE PROBLEMS WITH TRADITIONAL APPROACHES to planning have long been recognized. They include the attempt to make a ‘science’ of planning, with its subsequent loss of creativity; the excessive emphasis on numbers; the drive for administrative efficiency at the expense of substance; and the dominance of single techniques, inappropriately applied. Yet, decades later, strategists continue to struggle to propose clear alternatives to traditional processes.

Design offers a different approach and suggests processes that are more widely participative, more dialogue-based, issue-rather than calendar-driven, and conflict-using rather than conflict-avoiding, all aimed at invention and learning, rather than control.

But beneath all the hyperbole, we have to question what it would actually mean for business strategy if managers took the idea of design seriously. What if we tried to think the way designers do? Having studied how various kinds of designers work and create for the past decade, I offer the following ten suggestions as a starting point in the conversation.

1. We would realize that designing business strategy is about invention. For all their talk about the art and science of management, strategists, in the analytic search for ‘the one right strategy’, have mostly paid attention to the science. Taking the design metaphor seriously means acknowledging the difference between what scientists do and what designers do. Whereas scientists investigate today to discover explanations for what already is, designers invent tomorrow to create something that isn’t.

just one story about the future among

We all care about strategy because we want the future to be different from the present. But powerful futures are rarely discovered primarily through analytics. They are, as Walt Disney said, “created first in the mind and next in the activity.” This doesn’t deny analysis an important role, but it does subordinate analysis to the process of invention.

As an example of the tension between invention and analysis, take the Sydney Opera House, whose designer, Jørn Utzon, was awarded architecture’s highest honor, the Pritzker Prize, in 2003. It’s hard now to imagine Australia without the Sydney Opera House, but it’s quite possible that it would never have been built if initial estimates for the project had been accurate. In 1957, when Utzon’s proposal was selected, accountants estimated that the project would take five years to complete and cost $7 million. In reality, it took 14 years and cost more than $100 million. John Lowe, who chronicled the story of the opera house, quotes Ove Arup, an engineer who collaborated with Utzon on the project: “If the magnitude of the task had been fully appreciated… the Opera House would never have been built. And the fact that it wasn’t known…was one of the unusual circumstances that made the miracle possible.” Thank goodness the accountants got the analysis wrong.

2. We’d recognize the primacy of persuasion. If strategy is indeed an invention – just one story about the future among many – then it is always contestable. Leaders must therefore persuade others of the compelling wisdom and superiority of the story they have chosen. They must, in fact, make the story seductive; in selling their strategy, they must, to put it bluntly, treat employees like lovers instead of prostitutes.

It’s not easy to entice people into sharing an image of the future. After all, strategies in most industries today call on people to commit to something new and different, to step away from the security of what has worked in the past. This is never an easy sell, even for the most seasoned leaders. Like venturing into a new relationship, persuading others to share your vision works best when you issue an invitation instead of a command.

Designers understand this. Successful architects, for instance, know that to get their great buildings built, they must persuade clients to pay for them, and that requires helping clients visualize the end result. In fact, the more inventive the architect, the more critical the ability to conjure the image for the client and for what may be a very skeptical public. When Frank Gehry began sketching what would become the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, he already had a profound feel for what would draw a very traditional Basque audience to his stunningly inventive creation. Gehry explains his approach: “You bring to the table certain things…the Basques, their desire to use culture, to bring the city to the river. And the industrial feeling.”

Writing in The Los Angeles Times, architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff describes the result: “Gehry has achieved what not so long ago seemed impossible for most architects: the invention of radically new architectural forms that nonetheless speak to the man on the street. Bilbao has become a pilgrimage point for those who, until now, had little interest in architecture. Working-class Basque couples arrive toting children on weekends. The cultural elite veer off their regular flight paths so they can tell friends that they, too, have seen the building in the flesh.” Gehry’s Guggenheim persuades and seduces by connecting to the Basque’s past and pointing toward a new future. That is how strategies become compelling and persuasive: they show an organization its future without discounting its past. They tell us what we get to keep as well as what we must lose.

3. We’d value simplicity. Think of an object you love. Chances are that it is complex enough to perform its function well, but no more complex than it needs to be. In other words, it’s an elegant solution. No design is a better exemplar of simplicity and elegance than the little black dress, or ‘LBD’. The most striking aspect of the LBD, designed by Coco Chanel in the 1920s, is its simplicity. The LBD does not overprescribe or adorn, but instead offers a black canvas, which its wearer tailors to the function at hand: add pearls and heels to dress up; a bright scarf and flats to dress down. The possibilities are endless, making the LBD one of the most functional items in a woman’s wardrobe. But the LBD goes beyond mere functionality to achieve elegance: it lacks nothing essential and contains nothing extraneous.

What if we used the LBD as a model for business strategy? We would end up with strategies that would be neither incomprehensible to all save their creators, nor banal and self-evident. They would eschew the faddish and focus on enduring elements, incorporating a versatility and openness that invited their ‘wearers’ to add adornments to fit the occasion at hand. Perhaps most importantly, they would emphasize our positives while acknowledging our flaws – all in the service of offering us hope for a better (thinner) tomorrow.

4. We’d aim to inspire. One of the saddest facts about the state of business design is the extent to which we settle for mediocrity. We don’t even attempt to engage our audience at an emotional level, let alone to inspire. Yet the difference between great designs and those that are only ‘okay’ is the way the former call us to something greater.

Consider the differences between the San Francisco Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge. The Bay Bridge offers a route across the water. The Golden Gate Bridge does that, too, but it also sweeps, symbolizes, and enthralls. It has, like the Sydney Opera House, become an icon of the land it occupies. How many of our business strategies are like the Golden Gate Bridge? Too few.

5. We’d master the core skills first. Each of the designs we’ve looked at so far is inventive, persuasive, elegant, and inspiring. Yet all of them succeed because they also work well, and they do this because of the mastery of technical elements. The Sydney Opera House’s sail-shaped roof vaults required expert engineering. The Guggenheim Bilbao’s undulating titanium-clad exterior was possible only with the help of sophisticated computer modeling. And the little black dress worked because Chanel pioneered a synthetic fabric – jersey – that flowed instead of clinging.

If you examine the 1895 painting First Communion, you’ll see evidence of extraordinary technique; the layers of white in the young girl’s dress, in particular, are astonishing. Who was the artist? Pablo Picasso, who, at age 14, had clearly mastered conventional art. Now consider Guernica, which Picasso painted in 1937 to memorialize the Nazi bombing of the Basque village. There is little that is conventional about this painting, considered one of modern art’s most powerful antiwar statements. Picasso, who by this time was recognized as one of the most functional artists of the twentieth century, had moved beyond conventional technique, using his mastery to push the frontiers of art.

6. We’d learn to experiment. How does one move from mastery to brilliance? From technical competence to true innovation? By experimenting. Some design experiments take place in the mind; think of the strategic planning process, in which strategists imagine and test new futures – and some find their expression in physical prototypes. Some experiments are even conducted in the real world, and here I offer my only design story from the business world: IKEA. When the company’s visionary founder, Ingvar Kamprad, started out, he had only a general sense of what would become IKEA’s revolutionary approach to the furniture business. Nearly every element of its now-legendary business model – showrooms and catalogs in tandem, knockdown furniture in flat parcels, and customer pickup and assembly – emerged over time from experimental responses to urgent problems. Customer pickup, for instance, became a central element of IKEA’s strategy almost by chance, when frustrated customers rushed into the warehouse because there weren’t enough employees to help them. The store manager realized the advantages of the customers’ initiative and suggested that the idea become permanent.

7. We’d be more inclusive in our strategic conversations. The image of the solitary genius at work in his atelier is as much a myth in art, architecture, and science as it is in business. Design teaches us about the value of including multiple perspectives in the design process – turning the process into a conversation. The more complex the design challenge, the greater the benefits of multiple voices and perspectives.

Consider, for instance, the complex and political process of urban planning – in particular, the New Urbanism movement, which emerged from the experiences of the developers and architects of the innovative Seaside Community in Florida. What distinguishes New Urbanism from other architectural movements is its emphasis on wide participation. This participation takes the form of a charrette, an interactive design conversation with a long tradition in art and architecture. Derived from the French word meaning ‘little cart’, charrettes were used at the first formal school of architecture, the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, in the 19th century. As students progressed from one level to the next, their projects were placed on small carts, onto which students would leap to make their frantic finishing touches.

The charrette process used in New Urbanism projects is based on four principles: involve everyone from the start who might build, use, sell, approve, or block the project; work concurrently and cross-functionally (architects, planners, engineers, economists, market experts, citizens, public officials); work in short feedback loops; and work in detail. The charrette, I believe, offers a powerful alternative to the traditional strategic planning process by inviting the whole system to participate and by including local knowledge in the conversation.

8. We’d learn to talk differently. Of course, simply putting a variety of people in a room together is not enough. To produce superior designs, we must change the way we talk to one another. Most of us have learned to talk in business settings as if we are in a debate, advocating a position. But within a diverse group, debate is more likely to lead to stalemate than to breakthroughs: breakthroughs come from asking new questions, not debating existing solutions; they come from re-examining what we take as given.

As a case in point, consider the design of New York’s Central Park. In 1857, the country’s first public landscape design competition was held to select the plan for this park. Of all the submissions, only one – prepared by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux – fulfilled all of the design requirements. The most challenging requirement – that cross-town traffic be permitted without marring the pastoral feel of the park – had been considered impossible to meet by all the other designers. Olmsted and Vaux succeeded by eliminating the assumption that the park was a two-dimensional space. Instead, they imagined it in three dimensions, and sank four roads eight feet below its surface.

9. We’d work backwards. Most managers are taught a straightforward problem-solving methodology: define a problem, identify various solutions, analyze each, and choose one. Designers begin at the end of this process, as Stephen Covey has famously admonished, by achieving clarity about the desired outcomes of the design and then working backwards.

I’d like to illustrate this approach with a story that is close to home. Thomas Jefferson, who included education among his many passions and interests, devoted the last decade of his life to founding the University of Virginia. For Jefferson, the link between democracy and education was clear: without an educated populace, there was no hope of protecting the fledgling democracy that he and the other founding fathers had worked so hard to create. Jefferson’s university would produce free-minded graduates, and therefore it would need to differ from prevailing educational institutions in many ways: it would be a community where faculty and students work as partners to create a dialogue that produces the kind of learning that democracy requires. The typical large central building would be replaced with a collection of smaller buildings. This garden-encircled ‘academic village’ would be a community of learning where students would have unprecedented freedom in both the choice of curriculum and in governing their own behaviours.

To the modern observer, Jefferson’s genius may appear to lie in the beauty of the architecture he created. In reality, he took much of his architectural inspiration rather directly from the sixteenth-century Italian architect Palladio. Jefferson’s true genius lies in the power of the space that he created and its ability to evoke so vividly the purpose for which it was designed.

10. We’d start the conversation with possibilities. Great design, it has been said, occurs at the intersection of constraint, contingency, and possibility – elements that are central to creating innovative, elegant, and functional designs. But it matters greatly where you start. In business, we have tended to start strategic conversation with constraints: the constraints of budgets, of ease of implementation, of the quarterly earnings focus that Wall Street dictates. As a result, we get designs for tomorrow that merely tweak today’s. Great design inevitably starts with the question “What if anything were possible?” After all, if strategy is an invention, a product of our imaginations, and our assumptions are bound only by what we can imagine, then removing the assumptions that arise from the belief in constraints is job number one.

For my final example, we will turn to one of my favorite cities, Barcelona, and examine the story of its great unfinished cathedral, Sagrada Familia, designed by Antoni Gaudi. Gaudi was just 32 years in 1884, when he was named principal architect of the church known as the ‘Cathedral of the Poor’, which would be built entirely through donations. From the outset, Gaudi envisioned the cathedral he wanted to create – a ‘Bible in stone’, a soaring interior that evoked a forest and an exterior with towers that reached for the heavens. He resolved to design his cathedral as though anything were possible, even though the constraints he faced were seemingly insurmountable. Gaudi chose to disregard the usual constraints of time and money. “My client is in no hurry,” was his response to skeptics who doubted that the church would ever be completed. When funds became too scarce to continue construction, he went back to designing, building increasingly detailed plaster models and stepping out of his architect-builder role to raise funds personally.

The very real constraints imposed by the construction materials and techniques available at the time were impossible for Gaudi to ignore. Because the natural world served as one of the primary sources of inspiration in all of his designs, he aspired to create soaring spaces with natural light and found himself profoundly encumbered by the need for straight internal load-bearing walls and beams. Without the mathematical knowledge and modeling techniques available today, the physics of the cathedral’s construction were also a challenge as Gaudi sought to avoid the massive arches and buttresses common to the great medieval cathedrals.

occurs at the intersection of constraint,

In order to work around these constraints, Gaudi sought out new tools and techniques. He found two tools, little-used in Barcelona at the time, that would become the foundation of his work. The first was the ‘catenary arch’, a simple arch whose shape could be simulated by suspending a chain upside down. Gaudi was able to calculate the load-bearing demands placed on the massive cathedral towers by suspending small bags of sand from the inverted chain to mimic the weight that the towers would need to bear. This created a perfect model (albeit upside down!) of the possible shapes and dimensions that a real tower could take on. Computer models run on Gaudi’s towers demonstrate the surprising accuracy of his method.

The second tool that he discovered was a new material: cement. Combined with iron beams, brick or stone pillars, and a new roofing approach, cement allowed the exterior walls to bear most of the roof’s weight, giving Gaudi the freedom of interior design that he craved. Gaudi died at the age of 74 (ironically, run over by a streetcar on his way to church) with his cathedral only partially completed. Ten years later, the Spanish civil war came to the city, bringing construction to a halt. Rioters burned his workshop, destroying all of his plans and archives. Fortunately, the plaster models survived the fire and are being used today to guide the final phase of the cathedral’s construction. Completion is expected within the next 20 years.

All of the design stories told here are about possibilities made real, some of them against great odds. In order to achieve such designs, we must first aspire to achieve them, challenging the mediocrity of much of today’s design. We must also learn new skills, including the mastery of core technologies and the ability to persuade, to talk differently, to experiment. Finally, we must embrace new processes – processes that invite a more diverse set of perspectives into the strategic conversation, that work backwards from a clear sense of the outcomes that we want to create. And we must start our conversations with possibilities. The kind of exemplary designs discussed here are rarely achieved even in design – let alone in business. But as we all know, it is that which is hard to do that is most worth doing.

Jeanne Liedtka is the United Technologies Corporation Professor of Business Administration at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business and the former chief learning officer at United Technologies. She is the author of three books, most recently Solving Problems with Design Thinking: Ten Stories of What Works (Columbia University Press, 2013).

Cities, buildings, products, services, systems, and strategies all face the same need to combine expertise, insight, engagement and adaptation. It’s time to confront the tensions of design.

by and

NEARLY 40 YEARS AGO, Nobel Laureate in Economic Sciences Herbert Simon argued that, “everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones. Design, so construed, is the core of all professional training: architecture, business, education, law, and medicine are all centrally concerned with the process of design.”

Given the widespread attention given to design in the business press in recent years, it appears the time has finally come when the business world is taking this message seriously. Yet design is hardly the core of any current management training – or its practice. In fact, it’s not clear that we even agree on what design means. As two business academics long interested in this topic, our purpose here is to show the robustness of the notion of design; to examine the various forms ‘designing’ takes; and to explore its potential for helping people manage more effectively.

Design is both a noun and a verb. As a noun, it refers to an outcome, and some are superior to others: there are great designs, and there are mediocre designs. To appreciate the difference between great and mediocre design, consider a comparison of the Golden Gate and San Francisco Bay bridges. Both offer reliable transport across the water separating San Francisco and its neighbours – but the similarity ends there. The Golden Gate enthralls, sweeps, and symbolizes, inspiring art, music, and myth. The San Francisco Bay Bridge, meanwhile, merely gets the job done. Does this difference matter? We believe that it does – and that business has much to learn from this ‘tale of two bridges’.

Functionality is an insufficient pre-condition for a great design. The personal objects that people cherish do more than just work, they share a number of other characteristics: they seem simple but complete to their users; they contain nothing extraneous, yet lack nothing important; they engage at an emotional level; beyond their ability to serve function without fanfare, they hook their users in an almost sensual way; and finally, great designs manage to be simultaneously enduring and innovative. They connect to the past with a reassuring familiarity, while surprising users with their inventiveness.

The important lessons of ‘design as a noun’ turn out to be reassuringly straightforward: if you want great designs, seek simplicity, emotional engagement, and that sweet spot between the familiar and the new. And, of course, do the job well. And yet, if it’s all that obvious, why are we surrounded by so many mediocre designs?

That brings us to the tricky part: design as a verb. Like most things that are hard to do, this is where the competitive advantage lies. Better designing – of products, organizations, strategies – holds the key to unlocking the real potential of design for business. The basic attributes of successful designing are well-recognized: the process is synthetic, future-focused, hypothesis-driven, and opportunistic. It involves observation, the use of frameworks and prototyping. But peel back from these high-altitude accounts, and you will find that the particulars of designing involve varying approaches.

Consider the revolutionary architectural and social experiment of Brasilia, the most completely- planned city of the modernist movement. Rising from the largely uninhabited central plateau of Brazil in the 1950s and designed in exacting detail to be ‘the model city of the future’, it anchors a position at one extreme of design approaches, whereby the designer is evident, declaring his or her intentions, resisting compromise, and imposing his or her will on users.

At the other extreme are the lovely villages perchés (perched villages) of Provence. Evolving over time and through the participation of many, the hand of any single designer seems hardly visible. Yet these villages retain a sense of symmetry and coherence that suggests intention and conscious forethought – no less so than Brasilia.

Exploring the design continuum from the stark, fixed, and imposed, to the adapted, fluid, and evolving allows us to develop a deeper understanding of what constitutes ‘design as a verb’, and sets up an examination of the challenges of designing for business. To explore their range, we describe four disparate approaches to design.

First, we return to Brasilia, where the design tensions were resolved by coming down heavily in favour of the designer’s global knowledge and expertise, a controlled process, and a fixed design. Architect Oskar Niemeyer used established techniques and official principles to reach what he considered to be an optimal answer. We use the term ‘formulaic’ to describe this approach.

For modernist architects, the crises of the highly-industrialized cities of the world were reflected in their traffic, congestion, and poor standards of living. Only ‘total planning’, they believed, could resolve these problems. By creating a new kind of city, Brasilia’s designers set out to create a new kind of society, using architecture as an instrument of change. The modernist principles driving design included the organization of the city into separate zones for work, living, and recreation; the replacement of traditional streets with high-speed one-way avenues radiating out from the center; and the creation of superquandra – large apartment complexes containing standardized family units intended to break down traditional socioeconomic barriers. The resulting design is specified by a set of pre-existing principles, rather than emerging from a more open-ended process of experimentation. Brasilia’s design consciously resists attempts at adaptation, rather than encouraging them. It is meant to stay true to what it is – a ‘model’ city.

Consider the pronounced similarities and differences between the above process and the story of Ingvar Kamprad and his creation, IKEA. Kamprad’s personal ethic of thrift and simplicity provided the underlying values behind IKEA’s defining intention: “To create a better everyday life for the many by offering a wide range of well-designed, functional home furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them.”

In the IKEA story, we observe a more organic design process at work. Kamprad was more the visionary than the expert, more attuned to learning and adapting than to knowing and controlling. In a sense, he had no choice – he started without the power of bulldozers or a body of principles. He had, at best, the equivalent of a small number of people with shovels and only a general notion of what they were setting out to build. And so he adapted to the constraints he could not eliminate. Nearly every element of IKEA’s now legendary business model – showrooms and catalogs in tandem, knockdown furniture in flat parcels, massive stores readily accessibly by automobile, and customer pick-up and assembly – emerged over time as responses to urgent problems that the struggling furniture company faced. “Regard every problem as a possibility,” was Kamprad’s mantra.

Interestingly, the IKEA story also shares some characteristics of Brasilia. Both are intensely possibility-driven, with the designer’s hand evident and dramatic. Yet Kamprad’s visionary design process parts company with formulaic design by relying upon personal creativity, rather than formulaic technique, affording less control but more responsiveness to opportunity. The resulting design is never really fixed; it is meant to be flexible and adaptive. The fallible person – the visionary – takes over from the ostensibly infallible technique, enhancing the potential to experiment and learn.

This approach opens up the design process – making it a conversation among many people, all of whom should be recognized as designers. Two of today’s leading proponents of involvement in the design process are Andrea Duaney and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, founders of New Urbanism. Their first and best-recognized project, designed more than 20 years ago, was Seaside Florida, an 80-acre beachfront town on the Gulf of Mexico. Architecture Week called it “one of the most influential design paradigms of its era”; and Newsweek, “the most influential resort community since Versailles.”

What distinguishes New Urbanism from other architectural approaches is not only a different set of principles, but also its insistence on wide participation in designing, through the use of a process called a charrette. In the words of Duaney and Plater-Zyberk, “The charrette brings together all interested parties who are invited to offer direction and feedback while the plan is being created. It provides a forum for ideas and offers the unique advantage of giving immediate feedback to the designers while giving mutual authorship to the plan by all those who participate.” By convening a conversation that puts the entire system in the room, the architects control the boundaries, but not the conversation itself. Those involved are not merely consulted; they are engaged, and they become members of the design team. Put differently, all kinds of ‘quiet designers’ enter the process – bringing with them their local knowledge.

With the Seaside charrette, the architects created a context in which experts and users learned together, and out of which the design appeared. This process can be admittedly chaotic, which must be tolerated if creativity and consensus are to emerge. Like Brasilia, however, the design itself is eventually fixed. The charrette ends, and our quiet designers go home. Designing stops and construction starts.

In this approach, designing in the traditional sense – as practiced by identified designers at specific points in time and resulting in fixed designs – disappears. We now enter the world of evolving, or never-ending design, not by experts, but by communities in the course of living their collective lives.

This evolutionary design is found in the Linux operating system and the open source software process it pioneered. Linux is being designed with almost continuous adaptation in mind. In recounting the story of its origins, software designer Eric Raymond opens with a question: “Who would have thought that a world-class operating system could coalesce as if by magic out of part-time hacking by several thousand developers scattered all over the planet, connected only by the tenuous strands of the Internet?”

Linux’s success challenged many of the basic premises of traditional software design – foremost among them, that large projects need to be built like Gothic cathedrals, carefully controlled by a small band of experts who specify every detail and release their design to users only upon completion. Linus Torvalds, the originator of Linux, created this revolution by starting with a basic scaffolding offered by another programmer, sharing the source code, and inviting anyone interested to participate. He released revisions early and often, and above all, treated users as co-developers, building a “self-correcting system of selfish agents” whose pace of ongoing improvement was unprecedented. “The closed-source world cannot win an evolutionary arms race with open-source communities that can put orders of magnitude more skill time into a problem,” Raymond observed, because “given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.”

Like Duaney and Plater-Zyberg, Torvalds leads the conversation rather than writes the code. The ‘community’ does the designing, and designers and users become almost indistinguishable.

The four approaches outlined above reveal some of the core tensions of design and the various trade-offs that each approach makes. Following are four core tensions that hold valuable lessons for business.

Who should drive the design? The expert who knows better, who has the global, explicit knowledge, or the user who understands better, who has the local, tacit understanding? The paradox around deciding who designs involves the apparent trade-off between a reliance on experts and visionaries capable of radically innovative – but potentially difficult to implement – solutions versus a reliance on users with a tendency to produce ‘me-too’ designs that they enthusiastically execute.

Designer-dominated processes can have a clear advantage when it comes to producing designs characterized by radical change. The creation of Brasilia, for instance, was an audacious feat – it is unlikely that engaging a community of potential users would have produced such a futuristic model city. As users, most of us crave familiarity, not novelty; radical designs alienate us.

But at what cost do we exclude user involvement? The extent to which Brasilia actually achieved its designers’ ambitions is mixed. The standardization intended to produce equality produced, for many, a feeling of anonymity instead. In place of gaining an enriched community, many residents felt a loss of privacy. Instead of appreciating the orderliness of the space, they missed the messiness of street life. Despite the homogeneity of the superquandra, the old class distinctions remain. The risks of a design process that relies too heavily on experts are evident here.

If this is reminiscent of strategic planning in business, that is because formulaic design has been the corporate world’s preferred approach. This approach, with its emphasis on the designer’s worldview and its disconnection from local knowledge, represents the ‘yang’ of designing. It is ambitious, aggressive, and intrusive. It relies on techniques and information that, if inaccurate, can be fatal. Its detachment from users – the people who must live with the design – is a potentially fatal flaw. Yet it is capable of great change if the bulldozers are powerful enough and the terrain is reasonably predictable.

To succeed at significant change, either the formulaic or visionary designer must persuade users to accept a radical design, or conversational and evolving designing must engage users in ways that generate more-innovative designs. Designers who persuade others offer novelty and familiarity in tandem because they understand how users see the world.

This involves the tension between controlling a design process to achieve coherence and order versus opening up the conversation and risking some ‘messiness’ to achieve creativity and broader involvement. The inclusion of non-experts brings valuable ownership and local knowledge, but may also bring chaos and mediocre solutions. Getting more-innovative thinking from users themselves involves how this tension is resolved.

Successful leaders in both management and the physical fields of design seem to have an innate sense of when to allow flexibility into the conversation, when to tap the group’s potential for creating better solutions, as well as when to abandon the search for consensus to interject order from above. They have no formulas – just an acute sense of the particular, the potential, and the possible. These leaders/designers seem able to give up enough control to find creativity without losing coherence. Kamprad’s vision seems exemplary in its capacity to hold tight and let loose at the same time, in order to engage the collective creativity of the company’s employees and customers. There are enormous opportunities to bring this kind of conversational design into business.

Business leaders seeking better design thinking should pay careful attention to the challenges of preventing premature consensus emerging in the face of fear of chaos, and of maintaining the fluidity that is a prerequisite for breakthrough designs. Architect Frank Gehry notes that clients are rarely comfortable with the indeterminacy of an iterative process; they almost always push hard to fix the design and ‘end the uncertainty’. Conversational design challenges leaders in ways that formulaic and visionary design do not. Business cultures that centre on hierarchy, expediency, and authoritarian leadership get in the way of good conversations. We all know about opportunities that exist in the white spaces between divisions, regions, and functions of every company; what we do not know is how to tap these opportunities. Recognizing the role of conversations in exploring new possibilities can produce dramatic innovation.

The world does not stand still, but designs must – at least for a time: buildings have to be built, products brought to market, strategies implemented, and structures established. The dilemma in each case is how designs can be built to adapt, yet preserve their integrity. In other words, how can designing deal with change and continuity concurrently?

Former Intel chief Andy Grove has said that his firm’s strategy process evolved in alternating cycles of chaos and single-minded focus – sometimes adapting, sometimes closing. Companies that do nothing but change – constantly reorganizing, always envisioning some new strategy or other, bringing in yet another team of change consultants – never reach closure, and so are no better off than companies that never change. Even the most evolving designs have to be fixed for a time.

The key, we believe, is to get the basics right so that the specifics can easily be changed. As Raymond observed about software design, “You often don’t really understand the problem until after the first time you implement a solution. If you want to get it right, be ready to start over at least once.”