0 Introduction

0.1 The language family of Greek (↑Meier-Brügger 2003 E402ff; CAGL: 171ff)

Greek is a member of the Indo-European language family, which includes the majority of European and several Asian languages. The ancestor of these languages is called “Proto-Indo-European” or “Indo-European” (spoken ca. 4000–3500 B.C.).

The major branches of the Indo-European language family are (in roughly east to west order):

1. Indian subcontinent and Chinese Turkestan:

Indo-Iranian with Indic and Iranian; Tocharian.

2. Asia Minor, Greece, and Balkans:

From the 2nd millennium B.C.: Anatolian (best known: Hittite) in the east.

Greek in the west.

From the 1st millennium B.C.: Phrygian in Asia Minor.

From the early centuries A.D.: Armenian in the east and Albanian in the Balkans.

3. Italian peninsula: Italic, best known (and by far best attested):

Latin, ancestor of modern Romance languages (that developed from varieties spoken in the former Roman provinces): Romanian, Romansh, Sardinian, French, Dalmatian, Italian, Provençal, Spanish, Catalan, and Portuguese.

4. Other parts of Europe (particularly areas north of the Alps):

Celtic: Continental Celtic and Insular Celtic (British Isles and, as a result of migrations from there, Brittany).

Germanic: East Germanic (Gothic, Vandalic, Burgundian), North Germanic (Scandinavian), and Northwest Germanic (ancestor inter alia of German, Dutch, and English).

Balto-Slavic:

Baltic: inter alia Lithuanian, Latvian, Old Prussian;

Slavic: South Slavic (Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbian, Croatian, Slovene), East Slavic (Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian; the earliest attested [East] Slavic variety is Old Church Slavonic, used in Bible translations from the 9th century A.D.), West Slavic (inter alia Polish, Sorbian, Czech, and Slovac).

0.2 Overview of the history of Greek

(↑MB: E 304–318; Meier-Brügger 2003 E 417–421; BR: XIV-XV; Nesselrath: 135ff; Adrados 2005; Horrocks [detailed and up-to-date]; CAGL: 169ff, 527ff; BDF §1ff; Debrunner-Scherer; Reiser 2001)

Greek as a distinct language is probably the result of an evolutionary process that began ca. 2000 B.C., when a major wave of immigration set in from the Balkans into the region of modern-day Greece (or Ἑλλάς “Hellas”) where the immigrants eventually merged with the local population. The Greeks (or Ἕλληνες “Hellenes”, as they called themselves from the 8th century B.C.) spread in stages on the Aegean islands and (before the end of the 2nd millennium B.C.) on the west coast of Asia Minor, also in the east as far as the coast of the Black Sea, and (after 800 B.C.) in the west, especially in Southern Italy and Sicily (“Magna Graecia”). As a result of Alexander’s campaigns (334–323 B.C.) they temporarily gained control of most of the Levant and Middle Eastern countries reaching as far as India; so, for centuries the ←1 | 2→whole of the ancient world was thoroughly Hellenized. Hellenism, alongside Christianity, in fact became the principle driving force of Western civilization.

The spread of Hellenism included the spread of the Greek language, so much so that Greek was prominent at all levels even in Rome as in all the larger cities of the West well into the 3rd century A.D.1

After the division of the Roman Empire at the end of the 4th century, in the West Greek was superseded by Latin. In the East it came under increasing pressure as well until the Greek speaking area eventually shrunk to the size of what is modern-day Greece. There, however, the Greek language has held its ground until the present day against every kind of political and cultural threat.

During the Middle Ages the West was largely without the knowledge of Greek. In the 15th/16th century only it was rediscovered and restored to favour with Renaissance humanism calling for a return to the primary sources of Classical Antiquity (↑Latin slogan “ad fontes” [back] to the sources).

The earliest Greek texts available come from a period between ca. 1400 and 1200 B.C. They are written in a syllabic script (“Linear-B”) on clay tablets that were discovered by archaeologists in palaces excavated on the island of Crete (at Knossos) and on the Greek mainland (especially at Mycenae, Pylos, Tiryns, and Thebes). The language of these texts is called “Mycenaean Greek” (or “Mycenaean”). The Mycenaean Greeks had intense trading relations with the Phoenicians (Northwest Semites), which is shown inter alia by the fact that Semitic loanwords are attested already in their variety of Greek, e.g. ku-ru-so = kʰrūsos χρῡσός gold.2 After the fall of the Cretan-Mycenaean civilization ca. 1200 B.C. the Greeks appear to have lost their knowledge of writing almost completely (only in Cyprus a variety of the ancient syllabic script continued to be used for a time).

Later the contacts with the Phoenicians led to an innovation that turned out to be of revolutionary significance: before the end of the 8th century B.C. the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet that had been developed by West Semites in the early 2nd millennium B.C.; it comprised twenty-two letters that primarily represented only consonants (the intended vowels had to be inferred from the context). Since the Greek sound system differs significantly from the West Semitic one, the alphabet needed adjusting. Not only were changes introduced in the way letters represented consonants, letters also began to be used to express vowels, which was a step forward that is not to be underestimated in the history of writing (↑1e,3).3 Due inter alia to differences between the various Greek dialects the Phoenician alphabet was altered differently in different places, until in the 4th century B.C. the Ionic Alphabet (developed in Miletus) with its twenty-four letters was generally accepted as the standard alphabet for writing Greek (↑1).4

Ever since the alphabet was adopted in the 8th century B.C. to this day an ever-increasing number of texts written in Greek have been produced, at first mainly inscriptions, as time went by texts of every type, soon including literary and philosophical-scientific works as well. Many of these texts, ←2 | 3→a considerable number of them ancient ones, are available to us (either directly or in handed down form). These are the primary sources that are so vital to a solid study of the Greek language. Based on these the following varieties may be distinguished within the history of the Greek language:5

1. Mycenaean Greek, ca. 1400 to 1200 B.C. (↑above).

2. Ancient Greek, ca. 800 B.C. to A.D. 550, which may be subdivided as follows:

a) Pre-classical and Classical Greek, ca. 800 to 300 B.C.

A number of dialects have been identified that are marked by more or less extensive differences of sounds, word-forms, syntax, or vocabulary. One usually distinguishes four major dialects that are peculiar to a specific geographical area (termed “epichoric”):

(1) Ionic-Attic:

Ionic (in the middle part of the west coast of Asia Minor and on most of the Aegean islands as well as in the Greek colonies by the Black Sea and in Southern Italy);

Attic (in the district of Attica with Athens as its capital).

(2) Arcado-Cyprian:

Arcadian (various ancient dialects used in the district of Arcadia);

Cypriot (in Cyprus written in a native syllabic script [“Cypriot syllabary”]).

(3) Aeolic (on Lesbos and its environs as well as in the districts of Thessaly and Boeotia).

(4) West Greek (Doric in the wider sense):

Doric (from the town of Megara and the island of Aegina southwards, in most of the Greek colonies in Southern Italy and Sicily; with many local dialects inter alia in Corinth, Argos, Laconia, and on the islands of Rhodes and Crete);

North-West Greek (inter alia in the districts of Locris, Phocis, and Elis);

Pamphylian (in the Southern part of Asia Minor).

Alongside these epichoric dialects there were also literary dialects (originating in certain epichoric ones). These were used across dialect boundaries for composing works of particular literary genres, thus the Ionic dialect for writing the earliest known scientific prose (from the 6th century B.C. on early historians [“logographers”], in the 5th century Herodotus [“Father of History”], in the 5th/4th century Hippocrates [“Father of Medicine”]). The highest rank among the literary dialects, however, was held by the language of the “Homeric” epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, (put to writing from the 8th century B.C. on). This language appears to be an artificial variety developed by ancient Ionians on the basis of Aeolic; it had a sustained impact on the language of poetry (e.g. on Hesiod ca. 700 B.C.) as on Greek literary style in general.

In the second half of the 5th century B.C. Athens enjoyed a period of political and cultural prosperity (“Classical” period). Attic increased in importance among the Ancient Greek dialects, so much so that it rose to the rank of a standard language in which most of the literary works were written: the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides (6th/5th century), as well as the writings of the philosophers Plato (5th/4th century) and Aristotle (4th century), of the historians Thucydides (5th century), and Xenophon (5th/4th century), also of the orators Lysias (5th/4th century), Isocrates (5th/ 4th century), and Demosthenes (4th century). In view of the quality of these and other works, deemed classical, Attic is also called “Classical Greek”. And it is this variety that Greek courses at schools and universities are usually centred on.6

←3 | 4→In later times Attic continued to play an outstanding role: in the movement known as Atticism emerging in the 2nd century B.C., becoming particularly influential in the time of Augustus (1st century B.C./A.D.), and culminating in the 2nd century A.D. This movement declared Attic Greek to be the standard of correct language use; changes of sounds, vocabulary or grammar caused by a natural development of the language were branded as something to avoid. As a result the language split up into two main varieties: a) scholarly Greek, based on ancient usage, and b) popular Greek, subject to a continual natural development, spoken by the general public. This, essentially, is the origin of the rivalry that existed until recently between Katharévusa (Καθαρεύουσα “pure [language]”) and Dhimotikí (Δημοτική “[language] of the people”).7

b) Koine (also “Hellenistic Greek”), ca. 300 B.C. to A.D. 550

Attic was the official language of Alexander’s empire and of those of his successors (the “Diadochi”). During this period (336–30 B.C.), the so-called “Hellenistic” period, on the basis of Attic a supra-regional vernacular evolved as the lingua franca of the entire Hellenistic world, usually called “Koine” (ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος “the common language“). It gradually became the unrivalled standard with the ancient Greek dialects almost completely disappearing. Various sounds and forms characteristic of Attic Greek were replaced by ones more generally used (e.g. -ττ- by -σσ- [↑355a] or ξύν by σύν with [↑184q]); moreover there was an overall tendency towards greater clarity as well as simplicity of expression (something typical of any standard language; ↑p.637).

Apart from this vernacular there was a literary Koine. It was not used for poetry and literature in the narrow sense; for these, authors kept striving after an elevated style of Greek (based on Attic norms). It was, however, the medium on the one hand of technical prose as it is found e.g. in the works of the historian Polybius (2nd century B.C.), of medical writers such as Dioscorides (1st century A.D.), or of astrologers such as Vettius Valens (2nd/3rd century A.D.), on the other hand attested in romance novels such as those of Chariton and Xenophon Ephesius (1st/2nd century A.D.). Other works written in literary Koine are e.g. the “Letter of Aristeas” (“LXX” legend; 2nd century B.C.), the “Tablet of Cebes” (a popularizing philosophical dialogue; 1st century A.D.), and the writings of the Corpus Hermeticum (2nd/3rd century A.D.). A work to be placed at a lower level of style is the “Romance of Alexander” of Pseudo-Callisthenes (available form ca. A.D. 300); it is, however, of considerable interest to New Testament scholars involved in comparative studies, since its narrative style is particularly close to that of many parts of the New Testament. The most important testimony of a more elevated style of the Hellenistic vernacular is found in the philosophical “sermons” (διατριβαί) of Epictetus (1st century A.D.).8

Koine Greek is also the language of the Septuagint (“LXX”; translation of the Old Testament into Ancient Greek, with a variety of linguistic styles; most of it originating in the 3rd/2nd century B.C.),9 of the New Testament and of the “Apostolic Fathers”.10

3. Byzantine Greek (also “Medieval Greek”) is the language of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire, in use from the reign of Emperor Justinian (527–565) till the Fall of Constantinople to Ottoman Turks (1453), divided into the two inherited varieties, the Atticizing Greek of the Church and the scholars on the one hand, and popular Koine Greek on the other.11

4. Modern Greek is the language used by the Greeks under Ottoman (Turkish) rule (1453–1830), above all, however, since the founding of the modern Greek state (1830). The rivalry already men←4 | 5→tioned between the traditionalist “pure language” (Katharévusa) and the “language of the people” (Dhimotikí) was officially ended in the nineteen seventies in favour of the “language of the people”.12

Examples illustrating differences between historically distinguishable varieties of Greek:13

| “they carry into the house”: | “four”: | “when”: | |

| Mycenaean Greek: | woikonde pheronsi | (qetro-) | hote |

| Ancient Greek: | |||

| a) Pre-classical and Classical Greek: | |||

| • East-Ionic: | ἐς τὴν οἰκίην φέρουσι(ν) | τέσσερες | ὄτε |

| • Attic (Classical Greek): | εἰς τὴν οἰκίαν φέρουσι(ν) | τέτταρες | ὅτε |

| • Arcadian: | ἰν ταν ϝοικιαν φερονσι | (τζετρα-) | ὅτε |

| • Aeolic (Boeotian): | ἐν τᾱν ϝυκιᾱν φερονθι | πετταρες | ὅκα |

| • Doric (dialect of Argos): | ἐνς τᾱ̀ν ϝοικίᾱν φέροντι | τέτορες | ὅκα |

| b) Koine (inter alia NT Greek): | εἰς τὴν οἰκίαν φέρουσι(ν) | τέσσαρες | ὅτε |

| Modern Greek: | |||

| • Katharévusa: | στὴν οἰκίαν φέρουσι (stin ikían férussi) | τέσσαρες | ὅτε |

| • Dhimotikí: | στό σπίτι φέρνουν | τέσσερις | σάν |

0.3 New Testament Greek (↑Reiser 2001:29–90; BDF §1–7; Horrocks: 147–152)

The variety of Ancient Greek used in the New Testament is basically the vernacular of the Hellenistic period, Koine Greek. Philologically or linguistically, it is a variety that in most respects may be regarded as literary Koine. The style of language (i.e. the characteristic use of the language) encountered in the New Testament writings is to a large extent comparable to that of technical (particularly including romance) prose (↑p.4).14 Apart from Hebrews15 and parts of Luke and Acts it is, however, at a lower literary level; in some places it clearly approaches the style of the contemporary spoken language (as we know it from literary sources, most particularly from non-literary papyri of the Hellenistic period). In any case, no attempts to meet classical (Atticist) stylistic standards are in evidence within the New Testament.16 ←5 | 6→Because of this disregard of classical standards, the authors of the New Testament have been the object of ridicule to educated people ever since their time, which was dominated by Atticism (↑p.4). The New Testament style of language has often been classified as “vulgar” or as “ordinary street language”. According to Reiser such judgments are unjustified even with regard to the Gospel of Mark and the Book of Revelation. He adds: “The authors of the New Testament consistently demonstrate considerable literary skills and use their Greek with absolute confidence, even though that Greek did not meet the requirements of the educated upper class. […] The Church Fathers, therefore, spoke of the sermo humilis, of the ‘simple’, ‘lowly’ style of the New Testament, at the same time understanding humilis in the sense of ‘humble’.”17

One striking feature characterizing the New Testament variety of Koine Greek are the so-called Semitisms. This term refers to linguistic phenomena that cannot be explained in terms of normal Greek usage, but are thought to go back to Hebrew or Aramaic uses.18 Which of such unconventional phenomena exactly are to be regarded as Semitisms and what factors may have caused their appearance in New Testament Greek, is an issue that has been the subject of scholarly debate for centuries; none of the solutions proposed so far seems to stand up to rigorous philological scrutiny.

In the 17th and 18th centuries the deviations from the Classical Greek within the New Testament idiom were interpreted in different ways. The “Hebraists” explained them as being influenced by Hebrew usage, the “Purists”, apologetically motivated, regarded them as particularly “pure” Greek. Eventually the Hebraist view prevailed in that period.

Towards the end of the 19th century/the beginning of the 20th century there was a “paradigm shift”: A. Deissmann, J. H. Moulton, A. Thumb and others demonstrated by means of non-literary papyri discovered in Egypt and freshly studied Hellenistic inscriptions that most of the peculiarities of New Testament Greek are to be classified as Koine phenomena. In the light of subsequent philological studies the list of “Semitisms” has kept getting shorter and shorter.

There was, however, a counterreaction in the second half of the 20th century, which culminated in a second flowering of a rather extreme version of the “Hebraist” view, defended by several specialists.19 These (as many in the 19th century) thought that the peculiarities of New Testament Greek are best explained by positing the existence of a special “Jewish Greek”, a variety clearly distinguishable from the remainder of Koine Greek. The existence of such a distinct Koine dialect, however, was neither proven nor is it probable.20 The parts of the New Testament with a “Jewish” touch are on the whole, as Reiser convincingly shows, rather influenced by the language of the Septuagint, not unlike many protestant sermons of our time are by the language of the Authorized/King James Version or some other leading Bible translation (Reiser, of course, referring to Luther’s German translation).

←6 | 7→The linguistic phenomena that are usually classified as “Semitisms” are probably to be connected above all with the special content communicated by the New Testament; and this naturally impacted the utilized linguistic form in various ways. A major influence was no doubt exerted by the texts that had a foundational significance, especially by the Septuagint, the standard translation of the Old Testament into Greek (for their many Old Testament quotations the authors of the New Testament usually make use of this version).21 It is particularly the vocabulary that was affected22 by this (though less extensively than is sometimes assumed), almost exclusively a number of religious and theological expressions whose specific meanings arose through semantic borrowing, e.g.:23

| δόξα | profane: | opinion; honour, glory; | – |

| LXX/NT: | –; honour, glory; | concrete glory/splendour | |

(≈ Hebrew  kāḇôḏ) kāḇôḏ) |

|||

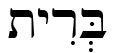

| διαθήκη | profane: | last will/testament; | – |

| LXX/NT: | last will/testament; | mostly agreement/covenant | |

(≈ Hebrew  bərîṯ) bərîṯ) |

|||

| ῥῆμα | profane: | word, saying; | – |

| LXX/NT: | word, saying; | also matter, thing | |

(≈ Hebrew  dāḇār) dāḇār) |

Certain Septuagint idioms, however, are well-attested (e.g. in the language of Luke, inter alia in Lk 1 and 2) being regarded as especially solemn and dignified, e.g.:24

| καὶ ἐγένετο …(↑217e) | And it came about … |

| ἀποκριθεὶς εἶπεν … or the like (↑239) | he answered (and said) … |

| πᾶσα σάρξ | all flesh (= every living/human being) |

| τὰ πετεινὰ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ | the birds of the sky (= the birds) |

Latinisms occur in the New Testament as well, but these are less significant than the Semitisms. A number of direct Latinisms are found inter alia in the following semantic domains: military (e.g. κεντυρίων centurio centurion/captain; outside the Gospel of Mark: ἑκατόνταρχος/ἑκατοντάρχης), ←7 | 8→administration (e.g. κῆνσος census capitation/poll tax), and commerce (e.g. δηνάριον denarius denarius). Furthermore several Latin suffixes are used as well, in the New Testament, however, only in names and comparable words (e.g. πρὸς Φιλιππησίους [< -enses] instead of Φιλιππεῖς or -έας to the Philippians; also ↑358h). There are also various expressions translated from Latin, e.g. terms designating certain offices such as ἀνθύπατος proconsul. Finally, we also find a handful of Latinizing idioms such as συμβούλιον λαμβάνειν consilium capere to come to a decision.25

For a summary of major differences between the Classical and the Koine/New Testament varieties of Ancient Greek ↑355–356.

0.4 On the history of Ancient Greek grammar

↑Schwyzer I: 4–11; LAW: 1129–1133; MB: E101; Nesselrath: 87–132; CAGL: 483ff; Pfeiffer: 1ff.

The earliest grammatical observations known to us were made in the pre-classical period (↑p.3) by people involved in reciting and handing down cultic hymns and the “Homeric” epic poems: they took note of strange looking letters, sounds, forms, words and phrases and tried to explain them.26 As early as the 6th century B.C. one was acquainted with the series of grammatical cases. Towards the end of the 5th century the Sophists (educational elite of the 5th/4th century) came to observe ways in which letters, syllables, rhythms, word-forms, word meanings, and style operate.

Such topics were explored also by Aristotle (384–322) and by Stoic philosophers (from ca. 300 B.C.). And it is these philosophers, essentially, that the grammatical terminology in use today goes back to (it has reached us by way of the Latin tradition). Stoic philosophers also developed sophisticated accounts of inflection and tense.

Scholars at Alexandria, the leading centre of learning of the Hellenistic period (↑p.4), started from these findings further refining them (here was the cradle of the combined study of the classical literature and language, classical scholarship).

Among the Alexandrian grammarians of the Hellenistic period the following are particularly significant: Zenodotus of Ephesus (born ca. 325 B.C.), Aristophanes of Byzantium (ca. 257–180) and, probably the most influential of the three, Aristarchus of Samothrace (ca. 216–144). They described inflection (declension and conjugation including irregularities; ↑23ff and 64ff) in its definitive form regarded as authoritative to this day. A pupil of Aristarchus, Dionysius Thrax (second part of the 2nd century B.C.) wrote down the new findings in a systematic manner in his Τέχνη γραμματική “Grammar”; this work served as a basis for teaching Greek until the 13th century A.D.

←8 | 9→In the period of the Roman Empire (from 27 B.C.) the two most significant ancient grammarians were active: a) Apollonius Dyscolus (first part of the 2nd century A.D.), who wrote numerous, mostly lost, works on the accents, prosody (measuring syllables based on length and pitch), morphology, and (extant in its entirety) syntax; b) his son Herodian (Aelius Herodianus; active in Rome; 2nd century A.D.), who wrote primarily about the accents and morphology; his studies are very accessible and mostly comprehensive and count as the principle source of grammarians’ writings from Late Antiquity.

The main emphasis of grammarians of the Byzantine (Medieval) period (↑p.4), the “National Grammar”, was on preserving and passing on examples of classical usage they considered normative, especially regarding vocabulary and word-forms (↑p.4). The writings that survive from that period do not provide us with additional insights into the grammar of Ancient Greek; still, they enable us to reconstruct a great deal from antiquity that we no longer have any direct access to.27

In the West, where Latin was predominant from the 4th century A.D., knowledge of Greek was lost almost completely (↑p.2). In the age of Renaissance humanism (15th/16th century) with its rediscovery of Classical Antiquity and its interest in studying the sources, a turnaround occurred.28 Guided by scholarly Greeks (many of them had fled their homeland at the fall of the Byzantine empire), a growing number of people learned Ancient Greek, at first in Italy, later, starting from there, north of the Alps as well. In fact, everywhere in the Christian West people began to study the Ancient Greek language and Ancient Greek literature again, and new text editions of ancient authors were produced. This movement was spurred on especially by the advent of movable type printing towards the end of the 15th century. Thus, as early as 1471 the first printed Greek grammar appeared in Venice, the so-called Ἐρωτήματα (“questions”) of Manuel Chrysoloras, which was soon followed by a large number of printed editions of writings in Ancient Greek.

Of the numerous humanists active in that age the following two must not be left unmentioned:

a) Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (1469?–1536), a leading European authority on Latin and Greek, who was active mainly in England, Germany, and Switzerland. With great intensity and exemplary methodology, he devoted himself to studying Ancient Greek writings, inter alia the classical authors, the New Testament, and the “Apostolic Fathers”, which led to a steady flow of publications. His most significant publication was, no doubt, the first printed Greek New Testament to be published (1516 by Froben in Basel); this edition (in a later, slightly revised form) became the authoritative basic text used by theologians and Bible translators for their work on the Greek New Testament until the end of the 19th century. Of special interest to grammarians is Erasmus’ rejection29 of the itacistic (Modern Greek) ←9 | 10→pronunciation of Ancient Greek, as it was taught by Reuchlin and Melanchthon, and his preference for the etacistic one, hence often called “Erasmian” pronunciation (though it was favoured by others before him; ↑1a).

b) Martin Luther’s friend Philipp Melanchthon (1497–1560), who along with others (including his great-uncle Johannes Reuchlin [1455–1522]) contributed substantially to the spread of Greek in German-speaking Europe during that period. Inter alia he published a Greek grammar,30 which was the standard Greek grammar of German-speaking people till the first half of the 19th century.

Well into the 19th century Greek grammars served mainly as tools for language teaching, textual criticism, and text interpretation. Meanwhile scholars had also begun to explore Greek as well as other languages regarding their family relationships and historical development (↑p.1ff). So, until the beginning of the 20th century there were two rival approaches to the study of Greek: a) the historical-comparative (clearly diachronic) approach, and b) the descriptive (more clearly synchronic) approach, specifically geared to the needs of the study of classical authors (classical philology). Already in the 19th century leading specialists such as G. Curtius (1820–1885) and K. Brugmann (1849–1919) realized the two approaches had a complementary role, a view that is regarded as axiomatic by modern representatives of Greek linguistics.31

The four-volume descriptive grammar Kühner-Blass (1890/92) and Kühner-Gerth (1898/1904) with its unsurpassed abundance of examples was produced in that era, likewise the first edition of the comprehensive school grammar of Smyth (1920), where the descriptive approach is predominant.

The historical-comparative approach, on the other hand, determines the large grammar of Brugmann-Thumb31 and its successor Schwyzer (1939/1950; with A. Debrunner as its final editor), which is still the standard historical grammar of Greek (though in the meantime parts of it are in need of revision), as well as the overviews of Greek linguistics of Hoffmann-Scherer (1969) and Debrunner-Scherer (1969) respectively, as well as (the most recent one) of Meier-Brügger (1992).

During the past one and a half centuries there have been a sizable number of further scholars contributing significantly at least to certain domains of Ancient Greek grammar, such as32 J. Wackernagel (1853–1938),33 F. Sommer (1874–1962), P. Chantraine (1899–1974), J. Humbert (1901–1980), E. Risch (1911–1988),34 M. Lejeune (1907–2000), more recently also Y. Duhoux. The following specialists inter alia have contributed towards fruitfully combining previous findings with insights of modern linguistics: F. R. Adrados (Sintaxis, 1992), R. M. Vázquez et al. ←10 | 11→(Gramática I, 1999), G. Horrocks (Greek, 1997/2010), A. Rijksbaron (inter al. in Boas-Rijksbaron, Grammar, 2019).

In most of the works mentioned so far, the primary focus was on Classical (Attic) Greek (↑p.3f). Since the first half of the 19th century Greek scholarship turned its attention specifically to the grammar of New Testament Greek as well. A variety of comprehensive treatments and studies on specific subjects began to appear.35

The most important comprehensive grammars of New Testament Greek36 include those of Winer,37 Buttmann,38 Blass,39 Robertson,40 Moulton-Howard, Radermacher,41 Springhetti42 as well as Blass-Debrunner (“BD”; English version of the 1959 edition: “BDF” [Blass-Debrunner-Funk]) and (its most recent revision) Blass-Debrunner-Rehkopf (“BDR”), today’s standard grammar for detailed exegesis (though parts of it are in need of revision, especially the syntax of the verb).43

Further important titles are referred to throughout the present grammar. Among the most relevant ones are those on syntax (as a whole or on certain parts considered particularly relevant):44 Zerwick (1963), Brooks/Winbery (1979), and Wallace (1995; comprehensive syntax); on discourse grammar: Levinsohn (1992/2000), and Runge (2010); on subjects going beyond these: Porter (1992: mainly on important areas of syntax; e.g. 2015: includes a wide range of subjects relevant to exegesis drawing on recent findings of a variety of linguistic and non-linguistic fields).

←11 | 12→0.5 Levels of text structures and the present grammar (↑inter alia Givón I: 7ff)

The present grammar, as already indicated in the preface, is meant to serve as a tool for theologians and others interested in interpreting the Greek New Testament. It is to help them explain in a reasoned way what the texts or parts of texts of the Greek New Testament (to some extent also of other relevant Ancient Greek writings) communicate linguistically.

Linguistic communication, i.e. the conveying or exchanging of informational content (by persons) for a particular purpose, is the main function of language. This applies to every (natural) language including Ancient Greek. Linguistic communication operates by means of texts45 of diverse types (invitations, requests, inquiries, offers, complaints, protests, appeals, birth and marriage announcements, death notices, anecdotes etc.).46 For a linguistic utterance to count as text (as defined by modern linguists) it needs not only to convey a certain content, it must also have a recognizable (communicative) function. This only makes it a (meaningfully) coherent text.47

The coherence of a text is closely connected with its linguistic structure. Text interpretation is about studying such structures and the elements they are made up of in order to understand as accurately as possible the intended content and objectives.48 And for a correct interpretation of the elements and combination rules of text structures we need to turn to lexicons and grammars, of course.

While lexicons tell us primarily about how words are typically related to content (the lexical meaning of words), grammars mainly deal with the forms, functions, and combination rules found at the various levels of text structures. In the present grammar (as in most other grammars) these levels are treated in separate parts, appearing hierarchically from the lowest to the highest (in most other grammars, the highest level, the textgrammatical one, is not taken into account as yet):49

1 Writing System and Phonology (↑1–20);

2 Structure of Words – Morphology (↑21–125);

3 Syntax (↑126–290; deviations from “norms”: 291–296);

4 Textgrammar (↑297–353; also ↑p.569).

In the appendices there are further matters to help text interpreters:

←12 | 13→Appendix 1: Classical and NT Greek: differences (↑355–356);

Appendix 2: Word-formation (↑357–371).

In the remainder of this introduction we will illustrate briefly the roles the various parts of the grammar may play in text interpretation; our example is the narrative text Mt 13:45f, a parable uttered by Jesus (as reported by Matthew) to point out the outstanding value of the “kingdom of heaven” he proclaimed (text function; main point):

| Πάλιν ὁμοία ἐστὶν ἡ βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν ἀνθρώπῳ ἐμπόρῳ ζητοῦντι καλοὺς μαργαρίτας· εὑρὼν δὲ ἕνα πολύτιμον μαργαρίτην ἀπελθὼν πέπρακεν πάντα ὅσα εἶχεν καὶ ἠγόρασεν αὐτόν. | Again the kingdom of heaven is like a merchant, searching for fine pearls. When he found one pearl of great value, he went away and sold everything that he had and bought it. |

Part 1 Writing System and Phonology (↑1–20) introduces us mainly

a) to the elements of the lowest level of text structure, to the letters of the alphabet, the sounds and syllables they represent, as well as to the diacritical and punctuation marks in use, a level without which the text structure is unlikely to either enter our minds or to make sense to us in any way at all, and

b) to the rules (“sound laws”) that help us to deal with grammatical peculiarities such as ζητοῦντι (< *ζητέοντι) searching (dat. sg.).

Part 2 Structure of Words – Morphology (↑21–125) is about the second level of text structure which is of crucial importance to text interpretation, the level of words (i.e. sound combinations indicating either [lexical] content or [grammatical] functions);50 most importantly it presents us with the various inflectional patterns (“paradigms”) enabling us to identify the specific word-forms of a text and to connect them with the intended functional category (more details are found in the syntax part), in particular

a) with declension forms (↑23–63) like μαργαρίτας, which as an accusative (plural of μαργαρίτης pearl; ↑26) in this text is best connected with the role of a direct object (answering the question “Whom or what [here: was he searching for]?” (↑23), and

b) with conjugation forms (↑64–125) like ἠγόρασεν, which as a finite verb form has the predicator role representing the core information of the sentence/clause (i.e. the action the subject entity [here: the merchant referred to] is said to be doing; ↑22f) and due to its classification as a 3rd person singular aorist indicative active (of ἀγοράζω to buy; ↑76 in combination with 92d and 96.5) points to the person spoken about (3rd person singular [↑64d], the subject entity [here: the merchant ]) who is said to have done something in the past (here: bought [that one pearl of great value]; ↑64–65).

The focus of Part 3 Syntax (↑126–290) is on the grammatical side of the third level of text structures, i.e. the level of sentences/clauses or propositions (content of sentences/clauses, “situations”; these are the most important structural components of a text as text (↑298); one of the greatest challenges of text interpretation is to understand these and to infer from them the overall content to be communicated by the text. This is the reason why the syntax part is as lengthy as it is; it tells us inter alia about

a) the function that words and phrases may have in Ancient Greek sentences (↑129–252), in the syntax of case forms (↑146–182) e.g. about the fact that dative noun phrases like ἀνθρώπῳ ἐμπόρῳ a ←13 | 14→merchant may occur as objects not only of verbs, but also of certain adjectives such as ὅμοιος like (↑179b), or in the section on the syntactic use of participles (↑227–240) about non-articular participles like εὑρών (ptc. aor. act. mask. nom. sg. of εὑρίσκω to find) frequently occurring as adverbial adjuncts (very frequently with a temporal nuance [↑229a–231d], here when he found … or the like [he sold everything …]),

b) the sentences and their constituents in Ancient Greek (↑253–265), e.g. about attributive modifiers of the head of noun phrases answering questions like “What kind of entity is the entity referred to by the head noun?” (↑260b–260n) and in what form it may occur in texts, inter alia as genitive noun phrase like [ἡ βασιλεία] τῶν οὐρανῶν [the kingdom] of heaven, as an adjective phrase showing concord like καλοὺς [μαργαρίτας] fine [pearls], as a participle phrase showing concord like [ἀνθρώπῳ ἐμπόρῳ] ζητοῦντι … [a merchant] searching … or even as a relative clause (↑next paragraph), and

c) the types of sentences/clauses occurring in Ancient Greek and the ways they may be combined (↑266–290), inter alia about independent declarative (main) clauses (↑267) like the ἐστίν-clause in Mt 13:45 and the sentence with the two predicators πέπρακεν (he) sold and ἠγόρασεν (he) bought, also about dependent (subordinate) clauses (serving as sentence constituents or attributive modifiers of a superordinate construction; ↑270ff), e.g. about relative clauses like [πάντα] ὅσα εἶχεν [everything] that he had (↑289a).

Part 4 Textgrammar (↑297–353; also ↑p.569) is about the highest level of text structures, that of the text. It is to show in what ways a text is different from the sum of its sentences/clauses as well as the ways in which the distinctive features of the grammatical (↑316–348) and the content (↑349–353) sides of the text structure relate to the coherence of Ancient Greek texts, here of a NT text, inter alia (for further details on our example ↑301; 303; 307):

a) connectives (↑354) like the adverb πάλιν again/furthermore (↑325c) that joins our text to the larger speech context and helps us towards recognizing its communicative function; or like the conjunctions δέ but (↑338a) and καί and (↑312c; 325c; 327) that serve to join the sentences/clauses or propositions/“situations” in question and help us to infer the intended content relations (↑352); similarly also (clause-like) participle phrases (↑312c) like ζητοῦντι … searching … , εὑρών … finding/ when he found … and ἀπελθών going away/he went away and; moreover, comparable to some extent, function words that refer back, “anaphorically”, or point forward, “cataphorically”, (↑346–348) like the article ἡ the [kingdom of heaven] or the personal pronoun αὐτόν [bought] it, which indicate what exactly (i.e. what specific concepts or entities) the speaker/writer refers to and which within the text establish a dense network of relationships that contributes decisively to the coherence of the text;

b) content words that may be connected with one particular domain of meaning (or “frame”; ↑313) and that relate to one another in a way that is relevant to conveying the text content, like ἔμπορος merchant, πιπράσκω to sell and ἀγοράζω to buy (commerce domain/frame) or also ἡ βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν the kingdom of heaven, an expression that, in the light of the wider context, is to be understood as a technical term; especially, however, the discernible (hierarchical) structure of the propositions/“situations” that the text content is made up of (↑312e for a corresponding display of Mt 13:45f).

1 For details ↑Reiser 2001: 4ff, and especially Horrocks: 124ff.

2 ↑inter alia Ugaritic ḫrṣ, Phoenician ḥrṣ or Biblical Hebrew  ḥārûṣ (↑HALOT s.v.). Also ↑MB: E 201–206; 309f.

ḥārûṣ (↑HALOT s.v.). Also ↑MB: E 201–206; 309f.

3 Most of the alphabetic scripts used in the world today originated here (↑Haarmann chapter 6), hence inter alia the fact that sounds such as /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, and /u/ are widely expressed by letters that originally stood for West Semitic (including Hebrew) consonants: ʾ  ʾ ā́lep̄) > A, h

ʾ ā́lep̄) > A, h  hēʾ) > E, y

hēʾ) > E, y  yôḏ) > I, ʿ

yôḏ) > I, ʿ  ʿáyin) > O, and w

ʿáyin) > O, and w  wāw) > U.

wāw) > U.

4 For details ↑MB: E 208 and Horrocks: viii–xx.

5 For details on the dialects ↑MB: E314–316, Nesselrath: 142–155, and Horrocks: 9–66 (with helpful examples). For a brief grammar of the Homeric language ↑BR §309–315.

6 Often works in other dialects supplementing it: Homer (archaic Ionic), Herodotus (Ionic), the lyric works of Sappho and Alcaeus (both ca. 600 B.C.; Aeolic), choral lyric (e.g. Pindar [6th/5th century], also remainders in the choral parts of Attic tragedies; Doric), the biographies of Plutarch (1st/ 2nd century A.D.; Koine replete with Atticisms), the NT (Koine). – More on Attic ↑Horrocks: 67–78.

7 Also ↑Debrunner-Scherer §154–159, Adrados: 198ff, and Horrocks: 133–141.

8 ↑Reiser 2001: 21–24, in more detail also Horrocks: 78–123 and 141ff.

9 For details on the language of the LXX ↑Reiser 2001: 23f, and Horrocks: 106–108.

10 For details ↑Reiser 2001: 6–28, Debrunner-Scherer §5f/114ff, and Horrocks: 147ff.

11 For details ↑Nesselrath: 162–167, especially Adrados: 226ff, and Horrocks: 189–369.

12 For details ↑Nesselrath: 167f, especially Adrados: 291–311, and Horrocks: 371–470.

13 Based on Risch: 2.

14 According to Horrocks: 147, it is “a reasonably close reflection of the everyday Greek of the majority of the literate population in the early centuries AD, subject, as always, to the influence of the ordinary written language of business and administration learned in school.”

15 Schwyzer I: 126, calls it “the first monument of Christian artistic prose” (original: “das erste Denkmal christlicher Kunstprosa”).

16 In contrast to what we find in several works of the higher type of literary Koine, including those of the Jewish authors Philo (philosopher, active in Alexandria; 1st century B.C./1st century A.D.) and Josephus (historian, active in Palestine and Rome; 1st century A.D.).

17 Original (Reiser 2001: 29f): “Die Autoren des Neuen Testaments zeigen durchweg beachtliche literarische Fähigkeiten und sind sich ihres Griechisch vollkommen sicher, auch wenn dieses Griechisch den Ansprüchen eines Gebildeten der Oberschicht nicht genügte. […] Die Kirchenväter sprachen deshalb vom sermo humilis, dem ‘schlichten’, ‘niedrigen’ Stil des Neuen Testaments; dabei verstanden sie humilis zugleich im Sinn von ‘demütig’.” For more on this topic also ↑Reiser 2001: 31–33, as well as Horrocks: 147–152.

18 One speaks of “Hebraism” or “Aramaism” depending on what specific language the phenomenon in question is thought to go back to, “Semitism” being used as a generic term.

19 Reiser 2001: 35, on details of the Semitism topic 33–49; ↑also Horrocks: 148–152.

20 ↑Reiser 2001: 35.

21 Uses that directly go back to the Septuagint, a version mostly translating “literally”, and uses that imitate its style of language, are termed Septuagintisms. These should not be confused with the (few genuine) Hebraisms in a narrow sense (“Hebraizing” uses that are not attested in the Septuagint) or with the (comparatively rare) Aramaisms (“Semitisms” that cannot be explained as Hebraisms). ↑Reiser 2001: 35.

Thus the transliterated foreign word κορβᾶν (Hebrew  qorbān; a cultic expression) in Mk 7:11 is a Hebraism in a narrow sense (interestingly, it is immediately followed by a translation into Greek: ὅ ἐστι δῶρον that is a gift [for God]). πάσχα passover (Aramaic

qorbān; a cultic expression) in Mk 7:11 is a Hebraism in a narrow sense (interestingly, it is immediately followed by a translation into Greek: ὅ ἐστι δῶρον that is a gift [for God]). πάσχα passover (Aramaic  pasḥā’ /

pasḥā’ /  pisḥā’; Hebrew

pisḥā’; Hebrew  pésaḥ) e. g. may be classified as an Aramaism (used also in the Septuagint).

pésaḥ) e. g. may be classified as an Aramaism (used also in the Septuagint).

22 Textgrammatical or textpragmatic regularities (↑297ff) no doubt were extensively affected, too (research into to these, however, is not sufficiently advanced to permit solid comparative studies). Also ↑Reiser 2001: 38.

23 ↑Reiser 2001: 38ff, where further examples are listed.

24 ↑Reiser 2001: 44ff, where further examples are listed.

25 Also ↑BDF §5, on occasional Coptic and Persian expressions also §6.

26 In the Classical period to such endeavours were joined in by discussions about issues regarding the philosophy of language, e.g. regarding the relationship between a word and the reality it refers to (↑Plato “Cratylus”): is it intrinsic (determined by nature φύσει) or arbitrary (by convention/ institution νόμῳ/θέσει)? – To modern linguistics “arbitrariness” is axiomatic (↑e.g. Bussmann: 32).

27 ↑Nesselrath: 104–116, for more details on this period including bibliography.

28 ↑Nesselrath: 118–121, for more details on this period.

29 In: De recta Latini Graecique sermonis pronuntiatione (1528). ↑Nesselrath: 120.

30 Institutiones Linguae Graecae (1st ed. 1518), later also Grammatica Graeca (↑Hummel: 746).

31 Brugmann-Thumb: VI and 2f; MB: E 101.

32 For particularly important titles ↑bibliography of the present grammar.

33 Wackernagel’s classic on syntax has recently been made available in English by David Langslow who updated the work by adding notes and bibliography.

34 Inter alia the co-author (responsible for the linguistic approach) of the grammar Bornemann-Risch (“BR”), which in many respects served as the basis of the present grammar (↑preface).

35 Note that the first grammar of New Testament Greek appeared much earlier (↑Lee: 62); it is the (785 page) volume of Georg Pasor (1655) Grammatica graeca sacra Novi Testamenti Dom. Nostri Jesu Christi in tres Libros tributa (Groningen: Coellen).

36 Many of these assume that users are familiar with Classical Greek (↑preface).

37 Georg B. Winer (1822) Grammatik des neutestamentlichen Sprachidioms (8th ed., revised by Paul W. Schmiedel; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 1897–1898); variously translated into English, e.g.: W. F. Moulton (1882) A Treatise on the Grammar of the New Testament Greek. (3rd ed. revised; Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark).

38 Alexander Buttmann (1859) Grammatik des neutestamentlichen Sprachgebrauchs. Berlin; translated into English by J. H. Thayer (1873) A grammar of the New Testament Greek. Andover: Draper.

39 Friedrich Blass (1896) Grammatik des neutestamentlichen Griechisch (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht).

40 ↑Bibliography of the present grammar (1st ed. 1914); Robertson’s grammar on pages 3ff contains a well-documented overview of the history of Ancient Greek grammar, with a special focus on the history of New Testament Greek grammar.

41 Ludwig Radermacher (1925) Neutestamentliche Grammatik: Das Griechisch des Neuen Testaments im Zusammenhang mit der Volkssprache (2nd ed. Tübingen: Mohr).

42 Aemilius Springhetti (1966) Introductio historica-grammatica in Graecitatem Novi Testamenti (Rome: Pontificia Universitas Gregoriana).

43 From the 4th edition (1913) Albert Debrunner (1884–1958) was responsible for this work, from the 14th to the 18th edition (1975–2001) Friedrich Rehkopf.

44 For the most important works on verbal aspect ↑192; especially noteworthy (in each case with comprehensive bibliographies) are the ones of Campbell (2007/2008a/b) and most particularly the volume of Runge/Fresch (2016) with its ground-breaking contributions.

45 In the case of living languages by means of written and spoken texts, in the case of “dead” languages (i.e. languages that are no longer spoken) such as Ancient Greek exclusively by means of written texts or (spoken) texts handed down in written form (↑2972).

46 For an overview of text types attested in the NT ↑305 (based on Reiser 2001: 92–194).

47 ↑297–302.

48 ↑308–314 for an overview of factors relevant to text comprehension and text interpretation.

49 Letters of the alphabet/sounds, words/word-forms and (normally) clauses/sentences, in themselves, do not amount to a text. Texts, however, are typically made up of adequately chosen and combined clauses/sentences, the clauses/sentences are (typically) made up of adequately chosen and combined words/word-forms, and the words/word-forms are (always) made up of adequately chosen and combined letters/sounds.

50 (Lexical) content is indicated by (lexical) content words such as the noun μαργαρίτης pearl, the adjective καλός beautiful/good/fine or the verb ζητέω to search, (grammatical) functions by function words such as the article ὁ/ἡ/τό or conjunctions as δέ but and καί and. Information about what may be indicated by content and function words is found in lexicons, information about function words also in the syntax and (if available) textgrammar parts of the grammar.