For a novel that takes as its central character a most conventional middle- aged, middle-class businessman, the plot of Babbitt is highly unconventional. The novel lacks any high drama, any life-shattering epiphanies, any serious confrontations with self or others. Indeed, one contemporary reviewer observed, “Babbitt simply grows two years older as the tale unfolds” (Mencken 138). In those two years, however, Sinclair Lewis captures in a series of chronological events the mundane realities of an average American life, and thus his unconventional plot perfectly mirrors its subject and becomes the ideal strategy by which to render it. The life of a conventional man such as Babbitt, once in motion, the plot suggests, simply moves forward of its own inertia. That seems definitely the case for George F. Babbitt, the forty-six-year-old realtor from the Midwestern metropolis of Zenith.

The novel’s first seven chapters record the details of a day in the life of such a conventional man. They introduce readers to Babbitt’s family: his devoted wife, Myra, and his three children, Verona, Ted, and Tinka; they enumerate the possessions that provide substance to his existence—his alarm clock, his camp blanket, his Boosters’ club button, for instance—as well as the details of his home that contribute to his assurance that he has achieved success; they record the man at work, dictating letters and planning real estate campaigns with his employees, every bit the “Solid Citizen” that he purports to be. Nothing beyond the ordinary worries of an ordinary man—that Verona, for instance, seems too preoccupied with “socialist” ideas, that Ted lacks direction, that a real estate deal may fall through—seems to bother Lewis’s ordinary hero, and yet as the novel opens, Babbitt has already begun to dream of a fairy girl who makes him feel confident and young, as if life is starting anew and not winding down into an inevitability. That note of discord in Babbitt’s life accounts for all that follows.

In subsequent chapters, Lewis reveals other aspects of Babbitt’s life: his memberships in social clubs and professional organizations that help him make valuable business connections and climb the social ladder; the dinner parties that he hosts (and for which he must scramble to purchase bootleg liquor, despite his support of Prohibition). Most important, they record his friendship with his college roommate, Paul Riesling, an even more dissatisfied citizen of Zenith who, unlike Babbitt, is willing to admit the disappointments in his life. Together the friends occasionally escape into the Maine woods, where they can dream of “what might have beens,” but they inevitably return to their conventional lives, any thoughts of rebellion temporarily quelled.

Life changes for Babbitt on the day that he is elected vice president of the Boosters’ club and discovers that Paul has shot his wife Zilla during another heated argument. When Paul is sentenced to prison for three years, Babbitt loses this important lifeline, and without its steadying influence, he soon finds himself thinking seriously about a fairy girl, someone who will bring change to his routine existence. When he meets an attractive widow, Tanis Judique, Babbitt believes that he has found her.

His affair with Tanis brings Babbitt into contact with her circle of flappers and bohemian friends, and he becomes more and more critical of the conservative views of Zenith’s other “solid citizens.” In fact, he soon voices support for some of the claims of the laborers who threaten a general strike in the city and espouses the liberal views of the socialist litigator Seneca Doane. These opinions as well as a change in his personal habits—he has begun to stay out late and drink to excess with Tanis’s crowd—soon cause him to be ostracized in the community and to lose business. No amount of persuasion on the part of his old friends, however, can convince him to return to his old ways. Only Myra’s return to the family home following a temporary absence nursing her sister helps Babbitt recognize that Tanis’s circle of friends, “the Bunch,” is in its own ways just as conventional as his own circle and to bring him back to his former self.

When Myra falls seriously ill with acute appendicitis, Babbitt nurses his wife to health and, relinquishing all thought of rebellion, rekindles their former intimacy. Soon he has also mended his relationships with his former friends and colleagues and returned to the fold of the Boosters. It is too late, he realizes, for another life. Yet Babbitt’s temporary flirtation with his dreams has subtly changed him. When Ted elopes with the neighbor girl, Eunice Littlefield, Babbitt supports his son’s plan to drop out of college to pursue his dream of working as a mechanic. Confessing to Ted that he had failed to do what he wanted to do with his life, Babbitt urges his son to resist the pressure to conform to others’ expectations and to follow his own path forward. During an era of conformity, such advice from a man whose name would come to signify everything wrong with the utterly conventional must truly have been the most unconventional element of Lewis’s novel.

In 1922, when Sinclair Lewis published Babbitt, the second of his five decade-defining novels, the nation was already cruising to what another chronicler of the era, F. Scott Fitzgerald, would eventually call the “greatest, gaudiest spree in human history” (Crack-Up 87). After a brief, sharp economic downturn in 1920, following the end of World War I, business was booming again in the United States, fueled by the conjunction of historical, economic, and cultural circumstances. That First World War, fought in what was now a devastated Europe, had left strong and intact America’s industrial base, and its factories, geared for efficient mass production, were soon manufacturing the automobiles and radios and other consumer goods that its citizens, who were benefiting from full employment and low inflation, were demanding. Those who could not afford to purchase these goods with cash were increasingly willing to exercise their credit and take advantage of the installment plan to enjoy today what they could pay for tomorrow, for it was difficult to resist the siren’s songs of the sophisticated new advertisers whose slogans promised such satisfaction from their products. The election of two Republican presidents, moreover, Warren G. Harding, who promised an era of “normalcy,” and Calvin Coolidge, who in 1925 famously pronounced that “the chief business of the American people is business,” effectively signaled the end of government regulation of industry and ushered in an era of laissez-faire economics and an unprecedented boom in the stock market that seemed to be embraced by all. Indeed, even the Teapot Dome scandal that began in 1922 did not provoke much outrage in a nation where so many were profiting from prosperity. Nothing, it seemed, not even its own apprehension about taking the world stage, could have derailed America’s political and economic ascendancy in the 1920s.

A four-passenger Ford sedan in 1923, by which time the automobile had become a symbol of the nation’s prosperity as well as the owner’s social status. (Library of Congress)

As if in confirmation of this ascendancy, Lewis created George F. Babbitt, a solid middle-class citizen of Zenith, Winnemac, a fictitious midwestern state adjacent to Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan (as the writer elaborated on its location in Arrowsmith, his subsequent novel). As its name signifies, Zenith, set deep in the nation’s heartland, is the epitome of modernity, the apogee of progress. Indeed, the novel’s first seven chapters, which relate the details of a representative day in the life of its title character, offer a compendium of the material items that define the successful realtor, an overview of the activities that comprise his professional and social lives, an introduction to the people with whom he associates, and insight into his opinions and beliefs, his hopes and dreams. From the novel’s beginning, Lewis clearly intends that both Babbitt and Zenith be types, representatives of the enterprising American businessman and the progressive American city that his work has created. Equally clear in those first seven chapters is Lewis’s satiric intention, for George Babbitt is also a caricature, drawn in broad strokes, a comic counterpoint to the heft of the world that Lewis re-creates in such realistic detail and that created its Babbitts. Something was amiss, in other words, in the Babbitt world, and Sinclair Lewis was determined to expose it.

As a representative of the solid middle class, Babbitt holds all the right ideas and follows all the proper paths, but that, Lewis makes clear, is part of the problem. A firm believer in the gospel of progress, he equates bigger, faster, and newer with all that is right about American society, so he values his alarm clock and electric cigar lighter, symbols of not only cutting-edge technology but also his social status. Driving his automobile gives him a sense of control that soothes away daily tensions: Accelerating from a traffic light, for instance, “he felt superior and powerful, like a shuttle of polished steel darting in a vast machine” (58). He takes pride that his children can get a first-rate education in their local school, which is, after all, “one of the biggest school buildings in the entire country!” (87). His chief satisfaction, however, is Zenith itself.

With its new office buildings, “austere towers of steel and cement and limestone,” aspiring to the heavens and “thrusting” the “fretted structures of earlier generations” from its center (1), Zenith has everything, including “zip” and “zest” and “bang,” that anyone could desire in a prosperous and growing modern American city. Indeed, “a stranger suddenly dropped into the business-center of Zenith could not have told whether he was in a city of Oregon or Georgia, Ohio or Maine, Oklahoma or Manitoba. But to Babbitt every inch was individual and stirring” (57). The city’s very homogeneity in fact inspires Babbitt’s confidence, reassures his beliefs, and confirms his self-importance. After all, he exhorts his audience of boosters at the annual meeting of the Zenith Real Estate Board, “Zenith and her sister-cities are producing a new type of civilization,” one whose “extraordinary, growing, and sane standardization of stores, offices, streets, hotels, clothes, and newspapers throughout the United States show how strong and enduring a type is ours” (203). Yet this very standardization, Lewis makes clear, is one of the perils of the progress and prosperity that effectively define Babbitt’s life.

To achieve this success, Babbitt has had to conform to the values and beliefs of, and cultivate relationships with, the members of his community, whose approval and support will determine his fate. Everything about his life, from the make and model of his automobile to the schools his children attend, from his political affiliation to his choice of church, from his leisure activities to the cut of his coat, is subject to scrutiny and evaluation, so Babbitt chooses the conventional. A member of the Elks, the Boosters’ Club, the Zenith Chamber of Commerce, and the Zenith Athletic Club, Babbitt joins all the influential civic organizations, where he enjoys the camaraderie of other like-minded “Good Fellows” and “Solid Citizens.” He also attends the Chatham Road Presbyterian Church and votes for Republican Party candidates. These memberships and affiliations as well as the editorial opinions expressed in the Advocate-Times, the Evening Advocate, and the Bulletin of the Zenith Chamber of Commerce are crucial to Babbitt’s worldview. Indeed, all of his opinions originate with them, perhaps because his favorite form of art and literature is the comics (83) but more likely because he would not wish to stray from the party line and “until one of [the city’s newspapers] had spoken he found it hard to form an original opinion” (83). Babbitt is without doubt a creation of his world, not of the self. Even “the large national advertisers fix the surface of his life, fix what he believed to be his individuality” (105).

The 1920s, with its jazz and flappers, its bathtub gin and speakeasies, was a decade of unprecedented social change, individual freedom, and intellectual rebellion. It was also an era of peace and prosperity that transformed the nation, creating a consumer culture that promised to keep American manufacturing humming. In the nation’s Zeniths, however, its Babbitts, its solid citizens and boosters, chiefly representatives of the business community, were determined that nothing should interfere with their safe and secure and comfortable lives, even if they had to sacrifice their individuality and conform to society’s expectations. Sinclair Lewis disclosed this dark underside of progress and prosperity in the Jazz Age, as determined as those boosters that they should see the folly in their sacrifice.

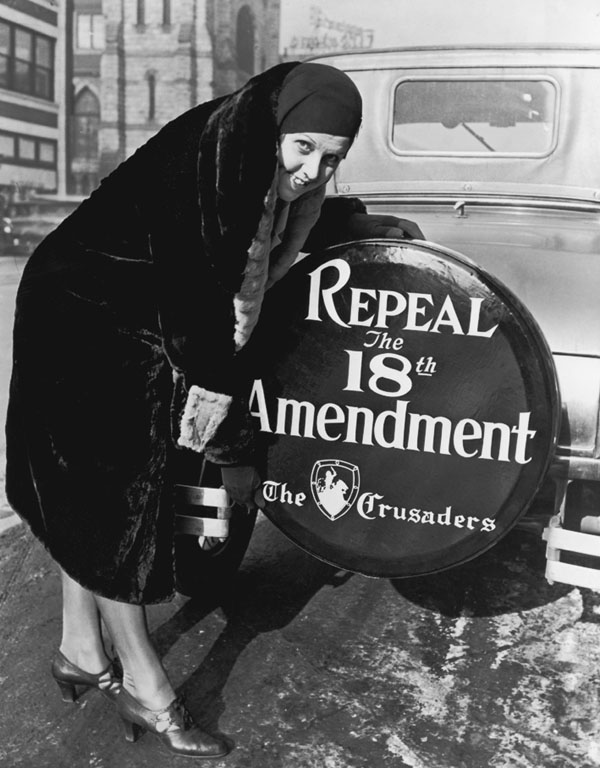

In 1927, a flapper supports the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment authorizing Prohibition, which made illegal the manufacture, transportation, and sale of “intoxicating liquors.” The thirteen-year “noble experiment” ended with passage of the Twenty-First Amendment in 1933. (MPI/Getty Images)

In October 1920, Sinclair Lewis published Main Street, the first of five novels published during the decade that exposed the realities of the Jazz Age in Middle America and propelled their author to the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1930, the first American writer to receive such recognition. If his popularity has waned in the intervening years, that was certainly not the case in the 1920s, when Main Street sold over one million copies in the two years between its release and the publication of his second major work, Babbitt, in 1922, a success that few other writers of the decade would achieve. Born and raised in the Midwest, Lewis clearly understood his native region, the habits of mind and being characteristic of Middle Americans, the quality of the life they lived, and while his re-creation of that world may have dismayed some, it rang true to so many others. Indeed, the writer who created George F. Babbitt added a word to the world’s vocabulary as well, for “Babbittry” became synonymous with the materialistic complacency and the mindless conformity of Lewis’s most famous character, ensuring Lewis’s place in American literary history.

The man who defined “Babbittry” was born Harry Sinclair Lewis on February 7, 1885, in Sauk Centre, Minnesota. Bookish rather than athletic in a region of the country where hunting and fishing and other outdoor pursuits were the standard for young boys, Lewis found it difficult to make friends, and he grew into a lonely and an ungainly young man who dreamed of escaping Sauk Centre. Escape came when his father, a physician, sent him to study at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1903, yet even there he remained friendless, a perpetual outsider who, rather ironically, given George Babbitt’s propensity for joining, found it difficult, if not impossible, to be one of the gang. At Yale, however, he did find support for his love of literature as well as encouragement for his early literary efforts, poems and short sketches that were published in the Yale Courant and the Yale Magazine. At Yale, he was also introduced to some radical socialist ideas, meeting the writer Jack London when he visited campus to lecture on socialism, and in 1906, under the influence of Upton Sinclair, briefly abandoning his studies to join Helicon Home Colony, the commune that Sinclair had founded at Englewood, New Jersey. For two months he fired furnaces to contribute to the joint effort and pursued his writing before returning to Yale, where he earned his degree in 1908.

Following graduation, Lewis set about to become a writer, struggling as most writers do for his first success. He traveled the country working low-paying jobs and even selling short story plots to Jack London, who, unlike Lewis, found it difficult to imagine storylines. Eventually he found work in a New York publishing house as a reader, copywriter, and salesman. He also began to sell his stories to Saturday Evening Post and to publish a syndicated book page carried in newspapers throughout the country. In 1914, Lewis published his first novel, Our Mr. Wrenn, which was well reviewed by the literary establishment. Six years and four minor novels later, he published the work that made him a major voice in American literature, Main Street (1920). Set in Gopher Prairie, Minnesota, the novel focused on Carol Kennicott, a sensitive and artistic young woman trapped in a stultifying and provincial small town in America’s heartland. Its view of life in that heartland deflated one of the nation’s sacred myths, that of the small town, with its industrious and virtuous citizens, its wholesome and nurturing environment, and prompted immediate controversy, propelling the novel to the best-seller list. Lewis’s next four novels, all published during the 1920s, made him one of the writers whose name is synonymous with the decade.

Babbitt, published in 1922, extended Lewis’s satirical critique of his America to its unbridled faith in business, its passionate embrace of materialism, and its mindless acceptance of the conventional and was as controversial as its predecessor. Lewis followed this success with Arrowsmith (1925), a novel that explored the challenges faced by an idealistic doctor and that was awarded the Pulitzer Prize (which Lewis refused to accept). Plunging again into controversy, Lewis published Elmer Gantry in 1927. This tale of a hypocritical evangelical minister was denounced by many religious leaders and banned in many cities. Two years later, Lewis closed out the decade with the last of his most important works, Dodsworth (1929), in which he examined the lives of the most affluent and influential members of American society and found them as empty and unfulfilling as his Middle Americans’. In five novels Lewis had exposed for all the dark underside of a roaring era.

Lewis continued to write in the years following his decade of success, publishing eleven additional novels, the most famous of which, It Can’t Happen Here (1935), imagined the election of a fascist to the American presidency. In the 1940s, he also toured the country with Lewis Browne, a rabbi and popular author, debating such questions as “Has the Modern Woman Made Good?” and “Is the Machine Age Wrecking Civilization?” in crowded lecture halls. But he never reclaimed his previous success, and his personal life was equally disappointing. He had married Grace Livingston Hegger, an editor at Vogue magazine, in 1914, just after the publication of his first serious novel, but they had divorced in 1925. Their only child, Wells Lewis, named after the British author H. G. Wells, whose work Lewis greatly admired, was killed in action during World War II. In 1928, Lewis married the journalist Dorothy Thompson, but by 1937, their relationship had soured. They divorced in 1942, and their only child, a son, Michael, died in 1975. Always a heavy drinker, Lewis had battled alcoholism from the late 1930s but was unwilling to give up drinking. On January 10, 1951, in Rome, Italy, Lewis died from the effects on his heart of advanced alcoholism; he was 65 years old.

The first American writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, Sinclair Lewis satirized American consumer culture, conformity, and the religion of business in his novels of Middle America. (Library of Congress)

In 1930, when Lewis won the Nobel Prize in Literature, punctuating his decade of achievement, the Swedish Academy praised “his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humor, new types of characters” and specifically cited Babbitt in its presentation speech. In his acceptance speech, Lewis praised many of his contemporaries, including Theodore Dreiser, Edith Wharton (to whom he had dedicated Babbitt), and Ernest Hemingway and then proceeded to lament that his nation’s readers and writers were “still afraid of any literature which is not a glorification of everything American, a glorification of our faults as well as our virtues.” In five novels published in the 1920s, Sinclair Lewis had refused to be that kind of writer. He had sought instead to reveal truths about American society, however painful, however unpopular. His Nobel Prize was in part recognition for this achievement.

Babbitt is the perfect antidote to the image of the Jazz Age that exists in the popular imagination. That image, which generally emphasizes the decade’s “roar,” nearly every aspect of which is associated with Prohibition, from its flappers and jazz cabarets to its bathtub gin and bootleggers and its gangsters and speakeasies, is certainly accurate. It does not, however, represent the whole of the 1920s. Indeed, far more representative of the decade is the title character of Sinclair Lewis’s 1922 novel, the genial realtor George F. Babbitt, a forty-six-year-old husband, father, Presbyterian, Republican civic booster in the shining midwestern metropolis of Zenith. He is, as H. L. Mencken asserted in his review of the novel, “America incarnate, exuberant and exquisite” (139), and Lewis renders his physical world, including its social and cultural realities, as well as his inner life (such as it is), including his attitudes toward and beliefs about his world, with such specificity that the 1920s exists in all its complexity and contradictions.

Prohibition, for example, the failed experiment in legislating morality and controlling personal habits, is in 1922 a fact of life, the provisions of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution having gone into effect just seconds after midnight on January 16, 1920, and Babbitt’s attitude about the law is typical of the majority of Americans’: “the way it strikes me is that it’s a mighty beneficial thing for the poor zob that hasn’t got any will-power but for fellows like us, it’s an infringement of personal liberty” (154). Preparing to host a dinner party for other solid citizens, Babbitt makes a pleasantly titillating excursion into criminality when he enters a tawdry speakeasy in Zenith’s Old Town to purchase a quart of gin (116–119), but he does not own a cocktail shaker, which was “proof of dissipation, the symbol of a Drinker, and Babbitt disliked being known as a Drinker even more than he liked a Drink” (121). Prohibition, Lewis’s solid citizens make clear during a discussion of the subject over drinks, was never intended for them, but rather for the irresponsible other guy. They never expected that their support of the law would prevent them from enjoying a convivial glass of wine or beer, and it did not (125–126). Such hypocrisy doomed the “noble experiment” almost from its beginning.

The catalogue of Babbitt’s possessions offers further insight into the era’s lifestyle and values. The Babbitt house, for example, with its concealed electrical plugs capable of powering the family’s electric lamps, electric fan, electric percolator, electric toaster, electric vacuum, and Victrola and decorated in the best of conventional taste, is a perfect example of “Cheerful Modern Houses for Medium Incomes” (116). The Babbitt motor car, moreover, is “poetry and tragedy, love and heroism” to its owner (26), much to the chagrin of his son, who argues the benefits of the new sedans with his more conservative father (80–81). In the modern age, after all, “a family’s motor indicated its social rank as precisely as the grades of the peerage determined the rank of an English family,” and Ted “aspired to a Packard twin-six and an established position in the motored gentry” (81). New and improved, bigger and better, the material goods of the Jazz Age reflected the public’s faith in progress as well as the triumph of consumer culture. If identity were to be represented by one’s possessions, then Babbitt, that Jazz Age Everyman, wanted to be certain that he owned all the right things, and he does.

Lewis’s depiction of Jazz Age youth culture as well as Babbitt’s reaction to it offers additional evidence of the era’s contradictions. He worries a bit about Verona, his Bryn Mawr–educated daughter, who thinks vaguely and ineffectually about “doing something worth while” (18) that sounds too much like socialism to her father (18) and in whose reading of “highly irregular poetry” by Vachel Lindsay and “highly improper essays” by H. L. Mencken “he felt a spirit of rebellion against niceness and solid-citizenship” (297). He worries even more, however, about his “motor-mad” son Ted, whose infatuation with the “movie-mad” (248) Eunice Littlefield and flirtation with correspondence courses threaten Babbitt’s plans for Ted’s own business success (82–95). Eunice, who, Babbitt suspects, smokes cigarettes and wears her hair bobbed and her skirts short and who, according to her father, has “pinned up twenty-one photographs of actors” to her bedroom walls, is clearly a flapper, and Babbitt is “bewildered” by her “worship of new gods” (248), uneasy with provocative behavior. The party Ted throws for his senior class only exacerbates Babbitt’s bewilderment and unease.

Babbitt, of course, “had heard stories of what the Athletic Club called ‘goings on’ at young parties.” Ted’s party confirms those stories. While none of the girls, all of whom have bobbed hair, wear lipstick and eye makeup, and dress in opulent fabrics, appears to have abandoned her corset in an upstairs dressing room, all seem to have arrived without wearing one, and they “danced cheek to cheek with the boys,” provocatively, with Eunice Littlefield a “flying demon” and Ted “maddest of all the boys” (250). Then Babbitt discovers the party’s “annex” (250), the dozen cars lining the street outside the house where the guests disappear to smoke and drink and perhaps engage in other immoral behavior. Appalled by the activities of “these children [who] seemed bold to him, and cold” (250), Babbitt and his wife consider their response and, concerned that they could jeopardize Ted’s status among his friends, decide to do nothing (251). Jazz Age youth culture was without doubt a sign of the revolution in manners and morals transforming the era, and it seemed to be leaving both young and old without a moral compass.

Babbitt may not have been the kind of experimental work of literary Modernism that the American expatriate poet Ezra Pound exhorted his generation of writers to create with his call to “Make It New.” It lacks the technical virtuosity of William Faulkner, the poetic disillusion of F. Scott Fitzgerald, the hard, muscular prose of Ernest Hemingway, the novelists who scholars and critics generally consider the most significant voices of the first half of the twentieth century. In its own way, however, Lewis’s satire of Jazz Age America exposes complex truths about the era. His realistic depiction of an average American in Middle America rings so true to the historical record that contemporary readers would have found it hard to dispute his views (although many businessmen and civic boosters valiantly defended its hero). Indeed, it is just the sort of novel that would have made Babbitt uncomfortable (assuming, of course, that he would have read it).

Prosperity fueled the roar in the Roaring Twenties. Although the decade began in economic depression (and would end there as well), three consecutive Republican presidents, Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover, convinced that promoting the country’s business interests would result in Hoover’s 1928 campaign promise of “A chicken in every pot, and a car in every backyard,” set in motion an era of unprecedented prosperity enjoyed by the vast majority of Americans. Granted, the Republicans’ laissez-faire policies toward commerce and banking and their series of federal income tax cuts, particularly for the wealthy, did little to alleviate the plight of the farmer, particularly those who grew staple crops such as wheat, corn, and cotton. After all, the nation’s dietary habits were changing, and synthetic fabrics such as rayon were transforming the fashion industry. Nor did they ease the depression in coal mining, textile and leather manufacturing, and shipbuilding. But those who worked in the automobile industry and in the various businesses that it spawned, such as gasoline service stations, motels, and diners, or manufactured the latest and most desirable consumer goods, such as the radio, the refrigerator, the washing machine, the telephone, and even cosmetics and cigarettes, suddenly found themselves with the disposable income to purchase these items. According to Frederick Lewis Allen in his groundbreaking history of the 1920s, Only Yesterday, “Between 1922 and 1927, the purchasing power of American wages increased at the rate of more than two per cent annually. And during the three years between 1924 and 1927 alone there was a leap from 75 to 283 in the number of Americans who paid taxes on incomes of more than a million dollars a year” (130). In the wake of World War I, business was clearly booming, and life without doubt was improving for nearly everyone in America. For the novelist Sinclair Lewis, conditions were also ripe for a satire of this world.

The primary focus of Lewis’s satire was the American businessman, the embodiment of the nation’s belief in progress and success and symbol of the triumph of business in the modern era. Whereas previous generations of American leaders had been firmly rooted in the learned professions, especially the law, the pendulum had begun to swing toward bankers, financiers, and industrialists in the aftermath of the Civil War, toward businessmen such as Andrew Mellon, J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and John D. Rockefeller, their millions tangible proof of success, their success worthy of emulation and indicative of a shift in attitudes toward what had previously been considered less distinguished professions. Indeed, in 1924 Henry Ford had even been encouraged to run for the presidency. After all, a man who had parlayed ambition, entrepreneurial spirit, and mechanical genius into an automobile empire must surely be capable of leading the nation to even greater prosperity and stability. The founding of The Wharton School for business studies at the University of Pennsylvania in 1881 and the Harvard Business School in 1903 clearly signified the increasing prominence of the businessman in American society.

By the 1920s, many Americans, like Lewis’s “Solid Citizen” and successful realtor George F. Babbitt, venerated the nation’s business interests. Early in Lewis’s novel, for instance, as Babbitt and his auto mechanic, Sylvester Moon, discuss the potential Republican candidates for the forthcoming presidential election, the realtor, repeating the pronouncement of Dr. Howard Littlefield, the “ ‘Great Scholar’ of the neighborhood” and “employment-manager and publicity-counsel of the Zenith Street Traction Company” (27), asserts that “what we need first, last, and all the time is a good, sound business administration” (32). If its businesses were booming, after all, everything would surely be right with the nation. Few things, moreover, inspire him more than Zenith’s thirty-five-story National Tower, a monument to “integrity” and “strength” and “decision,” qualities that move him to a kind of spiritual renewal. In fact, Lewis writes, Babbitt “beheld the tower as a temple-spire of the religion of business a faith passionate, exalted, surpassing common men” (14). While he may have attended Sunday services at the Presbyterian church, with all of the city’s other enterprising citizens, Babbitt had put his faith in a secular world and its gospels of success and wealth, and in this faith he was not alone.

Frederick Lewis Allen, in fact, asserts that “the association of business with religion was one of the most significant phenomena of the day” (148) and cites a number of compelling examples to support his point. At an annual convention of the National Association of Credit Men, for instance, Dr. S. Parker Cadman delivered a sermon on “Religion in Business” (148), while the Metropolitan Casualty Insurance Company issued a pamphlet on Moses, Persuader of Men, which assured, and reassured its salesmen that “Moses was one of the greatest salesmen and real-estate promoters that ever lived” and that he had conducted “one of the most magnificent selling campaigns that history ever placed upon its pages” (Allen 149). The best-selling nonfiction book of 1925 and 1926, moreover, was the advertising executive Bruce Barton’s The Man Nobody Knows, which argued that Jesus was “the founder of modern business.” After all, Barton observed, “He picked up twelve men from the bottom ranks of business and forged them into an organization that conquered the world,” using parables that were “the most powerful advertisements of all time” (Allen 149). An equally compelling example of this conflation of business and religion is Babbitt’s Reverend Mike Monday, “the Prophet with a Punch,” who sells salvation at “an unprecedented rock-bottom basis.” Indeed, according to his most recent report, “He had converted over two hundred thousand lost and priceless souls at an average cost of less than ten dollars a head” (108). Although some of Zenith’s solid citizens are at first reluctant to invite Monday, an evocation of the era’s famous evangelical preacher Billy Sunday, to preach in their city, when they learn that the evangelist “had turned the minds of workmen from wages and hours to higher things, and thus averted strikes” in other cities where he had erected his tabernacles, they quickly drop all opposition (108). The religion of business reassured all that profit margins and business strategies were sanctioned by a higher power. The businessman was simply part of the plan.

In America’s towns and cities, solid citizens like Babbitt channeled their evangelical faith in business through service clubs such as Rotary, Kiwanis, and Lions. Babbitt, for instance, wears in his lapel his Boosters’ Club button, which “associated him with Good Fellows, with men who were nice and human, and important in business circles” (10–11), and from his watch chain dangles a “large, yellowish elk’s-tooth— proclamation of his membership in the Brotherly and Protective Order of Elks” (10). He is also a member of the Chamber of Commerce and the Zenith Athletic Club, a social organization that marks him as one of the city’s distinguished citizens and gives him access to other equally important movers and shakers. Throughout the 1920s, membership in such organizations increased significantly. The Rotary Club, for instance, founded in 1905 and the most famous of the organizations, boasted 150,000 members by 1930 as well as 3,000 clubs in forty-four countries, evidence of its international influence. From 1920 to 1929, the Kiwanis Club, founded in 1915, grew from 205 to 1,800 chapters, and by the end of the decade, the Lions Club, formed in 1917, numbered 1,200 chapters (Allen 147). At weekly breakfasts, luncheons, or dinners members enjoyed good fellowship and made important connections with like-minded business and civic leaders. They also organized charitable events and social programs that confirmed their faith in the religion of business and supported the view of Rotary founder Paul P. Harris that “he profits most who serves best.” The Lions Club, for instance, began its work for the blind and visually impaired after Helen Keller addressed its international convention in Cedar Point, Ohio, in 1925, and almost from its inception, the Kiwanis Club focused its efforts on children and youth service. Harris firmly believed that business could be “a redemptive and regenerative influence in the lives of men—and nations” and proclaimed, “Honorable business is an elevating influence, making business men stronger, more straightforward, more sincere and purposeful, more humane and charitable than other men; making business nations more progressive, more enlightened, and less murderous than other nations.” In membership to these service clubs, a businessman like Babbitt could thus be assured that he was “the servant of society in the department of finding homes for families and shops for distributors of food” (46). Any profit from such service was merely the reward for vision, a value much admired among the business community (52).

At the forefront of the 1920s religion of business was the salesman and advertising man. American factories may have been churning out all sorts of new products, but their success depended upon the public’s willingness to purchase these goods, many of which, despite the new prosperity, were still expensive luxuries. It was left to the advertiser and the salesman to convince the public of the need for an electric washing machine or a radio or anything “new and improved” and of the ease with which they could have it now. What they needed to and did indeed create was a consumer culture, and they relied on increasingly sophisticated methods and the new psychology to achieve their goal.

Until the 1920s, advertising was largely a matter of announcing the availability of a product and informing the consumer of its use and benefits. During the 1920s, however, as mass production and lower prices resulted in an expanded American marketplace and increased competition for consumer dollars, advertisers shifted to persuasive tactics designed to convince the public that they needed and deserved these products. Consequently, as Frederick Lewis Allen observed, “The copywriter was learning to pay less attention to the special qualities and advantages of his product, and more to the study of what the mass of unregenerate mankind wanted—to be young and desirable, to be rich, to keep up with the Joneses, to be envied. The winning method was to associate his product with one or more of these ends, logically or illogically, truthfully or cynically” (142). A 1920s print advertisement for Lux Toilet Soap, for instance, features images of “Clara Bow, Betty Bronson, Janet Gaynor,” three famous actresses of the period, and “You,” promising in effect that women who washed with Lux would be as lovely as film stars. In other print ads of the period, the baseball hero Babe Ruth endorsed Old Gold cigarettes and claimed that Red Rock Cola was “the finest cola drink I ever tasted!” The appeal of such advertising was psychological, focusing on consumers’ unfulfilled desires or needs, and connecting their fulfillment to a specific product. And if that product were connected to a celebrity, so much the better. After all, in the 1920s, when baseball was the national pastime, most men would have been pleased to be compared to Babe Ruth, and in an era that celebrated youth, most women would have been flattered to look like Clara Bow, the nation’s “It” girl.

The power of advertising to change public perceptions and habits is perhaps best illustrated by the campaign against the social taboo of women smoking in public engineered by Edward Bernays, the father of public relations and nephew of the psychologist Sigmund Freud, in the late 1920s. Throughout the decade, the American Tobacco Company had sought in its print advertisements to make smoking fashionable for women through images of attractive young women, as well as actresses, smoking Lucky Strikes. In one ad, women were also exhorted “to keep a slender figure … Reach for a Lucky.” Legitimizing public smoking, and even smoking itself, for women, however, proved a difficult task, so in 1929, Bernays enlisted a group of models to march in the New York City Easter Parade and alerted reporters to expect a unique event. When the models stopped, lit their Lucky Strikes, and openly smoked their “Torches of Freedom,” cameras captured their bold assertion of independence, and journalists reported the event to a national audience. Soon enough, resistance to change collapsed, and women were enjoying yet another male privilege. Such was the power of advertising and public relations to effect social and economic change and thereby create a consumer culture unique to the Jazz Age.

Lighting their “Torches of Freedom,” women puff at their Lucky Strike cigarettes during the 1929 New York City Easter Parade in a gesture of freedom and absolute equality with men. The demonstration was organized by the “father of public relations,” Edward Bernays, for his client, the American Tobacco Company. (Underwood Archives/Getty Images)

In fact, “consumer culture,” according to Liette Gidlow, “was a defining element of public life in the 1920s, and the 1920s were a defining moment in the development of consumer culture. Though consumer goods and advertising, of course, predated the 1920s, a mature consumer society did not” (163). By the end of the decade, however, the American people had developed new attitudes toward material goods and their consumption as well as consumer credit, and “increasingly, American life,” according to Laurence B. Glickman, “not just economically but culturally, centered on mass consumption” (16). For many, the more conspicuous the consumption, the better.

Sinclair Lewis spends much of Chapter One of Babbitt cataloguing his hero’s possessions and his attitude toward them. “A man whose god was Modern Appliances” (5), he is “proud,” for instance, of being awakened by “the best of nationally advertised and quantitatively produced alarm-clocks, with all modern attachments, including cathedral chime, intermittent alarm, and a phosphorescent dial” (4). He is also relieved, after admitting to himself that his garage is “the only thing on the place that isn’t up-to-date,” to survey his “altogether royal bathroom of porcelain and glazed tile and metal sleek as silver,” complete with clear glass towel bar set in nickel, a tub “long enough for a Prussian Guard,” and a “sensational exhibit of toothbrush holder, shaving-brush holder, soap dish, sponge dish, and medicine-cabinet, so glittering and so ingenious that they resembled an electrical instrument board” (5). After shaving with a new disposable razor blade, he frets that the trousers of his brown suit need pressing and rejects outright his wife’s suggestion that he wear the coat of the brown with the trousers of his blue suit. “What do you think I am? A busted bookkeeper?” he rails. His B. V. D. undershirt, however, which distinguishes him from his father-in-law and partner, who wears “tight, long, old-fashioned undergarments” (9), restores his equilibrium, as does the “donning of his spectacles,” which transform him into the very image of “the modern business man; one who gave orders to clerks and drove a car and played occasional golf and was scholarly in regard to Salesmanship” (9). By the time he has put on his “well cut, well made, and completely undistinguished” suit (9); transferred the contents of his pockets, about which he feels “earnest” and which include a fountain pen and silver pencil; his “loose-leaf pocket note-book”; and his watch-chain, to which are attached a silver cigar-cutter, seven keys, a yellowish elk’s-tooth, and, of course, a good watch, from his brown to his gray suit (10); and stuck in his lapel his Boosters’ Club button (11), George Babbitt looks every bit the “Solid Citizen” he believes himself to be (9).

This catalogue of items that defines George Babbitt not only to himself but also for society captures the profound change in the relationship between the individual and material goods that occurred during the Jazz Age. Whereas previous generations had been defined by relatively objective criteria such as race, religion, class, geographical region, and occupation, the new consumer culture prompted people to identify less with the things they produced and more with the goods they purchased. As Kirk Curnutt observes, “The explosion of consumable goods provided individuals with new tools for packaging their personalities in vibrant and captivating ways, which fell under the general rubric of style” (91). While Babbitt’s style is hardly vibrant or captivating, it does indeed represent him. Everything about his appearance, his house, his car, his amusements and leisure activities, is designed, in fact, to signify his sense of self and confirm his membership in his class, equally important in the 1920s, when success, and especially business success, depended on the individual’s willingness to conform to established patterns, customs, and beliefs. Babbitt’s elk’s-tooth and Boosters’ Club button, emblems of his group identity, are thus as important to his selfhood as his purple knitted scarf, “his only frivolity” (9), into which he inserts a “snake-head pin with opal eyes”(10). “Style,” as Stuart Ewen defines the term, “was a way of saying who one was, or who one wished to be” (79), and, as Lewis makes clear in his initial description of Babbitt, in a consumer culture identity was increasingly a matter of commodities. Ewen confirms this shift, asserting, “The emerging market in stylized goods provided consumers with a vast palette of symbolic meanings, to be selected and juxtaposed in the assembling of a public self” (79).

Advertisers had done their job well. They had created a demand for consumer goods, a demand rooted not only or even primarily in utility and quality but also equally or even more importantly in personal preference and selfhood. Consumer culture, however, also depended on purchasing power, the ability to pay for desired goods, many of which, including the automobiles and electrical appliances that the era’s Babbitts worshipped, were still prohibitively expensive. Granted, wages had risen significantly throughout the twentieth century, increasing the public’s disposable income, but Americans traditionally believed in the value of thrift. They did not replace an item simply because manufacturers had released a new and improved model or they had tired of it, and they saved for a rainy day. If consumers were going to be persuaded to buy, they would first have to accept a newly evolving definition of thrift, one that transformed it, according to Lauren Rule Maxwell, into a “form of consumption” (313). Only by erasing the stigma of debt would the nation’s business and economic interests make credit and installment buying socially acceptable to the public.

To change the buying habits of the American consumer, the 1920s, according to Curnutt, “witnessed a vilification of financial restraint” (105). Newspapers and magazines published editorials and features that challenged traditional concepts of thrift, calling it the “new menace” and a serious “dilemma” (Curnutt 105) and making saving seem an old-fashioned virtue. Some even suggested that it was a form of hoarding (Glickman 17). Consumers were also encouraged to develop a sense of entitlement about the new products on offer in the marketplace. They had worked hard for their money and should not have to deny themselves the pleasure of ownership, especially when installment buying made it easy to enjoy their purchases as they paid for them. Throughout the decade, Americans experienced what the economist Martha L. Olney calls a “consumer durables revolution” that saw savings fall from 7.1 to 4.4 percent between 1898 to 1916 and 1922 to 1929 (“Advertising” 489–91) and overall consumer debt rise to $7 billion (Curnutt 107). In fact, according to Curnutt, debt had become “a badge of bourgeois pride as securing credit meant that one had not only been deemed a reliable borrower but that one possessed value in the marketplace” (107). By the end of the 1920s, when shopping had for the first time become a type of leisure activity, it was clear that Americans had changed their view of debt (even buying stocks on margin) and that yet another cultural shift had occurred in the nation.

One perhaps unintended consequence of prosperity and the changes that resulted from it was a stultifying conformity among the nation’s middle-class majority of which Babbitt was a chief representative. H. L. Mencken, the iconoclastic cultural critic and editor of first the Smart Set and then the American Mercury, two influential magazines whose audience was distinctively highbrow, coined the term “booboisie” to describe this group of uneducated, uncultured mindless boosters and mediocrities who held sway in the nation, and Sinclair Lewis ridiculed them in Babbitt. Having surrendered to the nation’s business interests, embraced commodity culture, and profited in doing so, the middle class sought now to consolidate its position and thus saw as threats any person or ideas that challenged their comfortable existence. Any talk of strikes or unionism, for instance, smacked of socialism and challenged the capitalist system on which the nation’s prosperity had been built. Any talk of natural selection or evolution, such as John Scopes was teaching to impressionable high school students in Dayton, Tennessee, undermined the Christian teachings on which its system of law and justice was built (as well as man’s belief in his superiority). Any failure to contribute to charitable campaigns or join civic organizations was an act of selfish individualism that threatened the good of society. While the 1920s lives in the popular imagination as a “roaring” decade, it was also, rather ironically, an era of social and political conservatism and conformity, of mass consumption and mass culture that some, including Sinclair Lewis, were determined to expose.

Lewis’s representative of middle-class conformity, George Babbitt, is simultaneously the embodiment of its critique, and the writer locates the problem in the “standardization of thought” (110), of which his protagonist is also the epitome. While Babbitt is vaguely aware of some dreams and desires unfilled by his personal and professional lives as well as the material possessions that represent him, he seldom thinks clearly or for long about the reasons for his dissatisfaction and probably lacks the facility of judgment to know himself. Woefully ignorant of literature, history, geography, and anything international, he rarely reads a book, preferring instead popular magazines and the local newspapers, where he can find the comic strips, “his favorite literature and art” (83), and takes all his opinions from these publications or trusted authorities such as his neighbor Dr. Littlefield or his minister or fellow boosters. Asked his opinion on a preacher who takes the oath of mayor wearing overalls, for instance, he “searched for an attitude, but neither as a Republican, a Presbyterian, an Elk, nor a real-estate broker did he have any doctrine about preacher-mayors laid down for him, so he grunted and went on” (23). Later, when his son Ted seeks his advice about correspondence courses, Babbitt finds himself “again without a canon which would enable him to speak with authority. Nothing in motoring or real estate had indicated what a Solid Citizen and Regular Fellow ought to think about culture by mail” (87). (Although the slick brochures advertising the courses initially give him pause, he eventually supports conventional public education, for which he is already paying.) Babbitt speaks in clichés and peppers his conversation with slang phrases such as “by gee, by gosh, by jingo” (14) that suggest an inability to frame an original thought. He also holds all the popular views because ultimately what he wants most is to be a hale and hearty good fellow and one of Zenith’s respected solid citizens. Tempted for a time to pursue the alternate path of Zenith’s few free-thinking bohemians, he feels the weight of the community’s approbation and eventually submits to the pressure, grateful to the point of tears when Vergil Gunch invites him to join the Good Citizens’ League (421).

In his 1922 Smart Set review of Babbitt, H. L. Mencken, who shared Lewis’s views and sensibility, calling himself “an old professor of Babbittry,” praised the novel’s realistic portrayal of Jazz Age America and of Babbitt, “the average American of the ruling minority.” Babbitt, he declared, was not a character but rather “an archetype,” and he represented, so far as Mencken was concerned, everything wrong in the nation: “It is not Babbitt that shines forth most gaudily, but the whole complex of Babbittry, Babbittism, Babbittisimus… . His every act is related to the phenomena of [his] society. It is not what he feels and aspires to that moves him primarily; it is what the folks about him will think of him. His politics is communal politics, mob politics, herd politics; his religion is a public rite wholly without subjective significance; his relations to his wife and children are formalized and standardized; even his debaucheries are the orthodox debaucheries of a sound business man. The salient thing about him, in truth, is his complete lack of originality—and that is precisely the salient mark of every American of his class” (139). Babbitt’s mindless conformity, his inability to think for himself, as Mencken saw it, compromised every aspect of his and the nation’s life, making both inauthentic and fraudulent. It was the underside of the American Dream, the price of prosperity, and Lewis had clearly exposed the truth for all to see.

Business was booming in the 1920s, fueling the nation’s prosperity. The advent of new consumer goods such as the radio and the electric toaster coincided with an increase in both jobs and wages and the public’s pent-up postwar desire for luxuries, or at least modern laborsaving appliances such as the electric vacuum cleaner, to create a consumer-spending spree that reignited America’s faith in capitalism. Businessmen such as Henry Ford embodied the American ideal of the self-made man (Ford was even encouraged to run for president), and the economic policies of the decade’s three Republican presidents signified that protecting America’s business interests was in the best interest of the nation.

Any doubts about those business interests were assuaged by the developing rhetoric of the religion of business. By focusing on the moral and ethical responsibilities of the businessman and engaging the business community in charitable work, business organizations such as the Rotary Club and the Lions Club helped perpetuate the view that the nation’s businessmen were as interested in doing good as in making money. By linking religious metaphors to business interests, the gospel of wealth and the ideal of success were no longer associated with materialism but rather with the good life. The businessman was no longer a shyster but a respected member of the community. Capitalism and Christianity were natural allies.

The following documents reveal the veneration of business, and especially the advertising man, that developed during the Jazz Age. The first document finds the founder of the Rotary Club reflecting on the organization’s success, which he attributes in part to its melding of business and moral principles. The second, an excerpt from Bruce Barton’s The Man Nobody Knows, which topped the nonfiction best-seller lists in 1925 and 1926, makes clear the connection between business and religion that developed during the Jazz Age by arguing that Jesus was the first advertising man and attributing his success to his salesmanship.

… Big dreams of Rotary are gradually coming true, and encouraged by past performances, we dare to dream again and of even bigger things. I sometimes see, or think I see, Rotary the harbinger of a general world wide philosophy of business and of life, with happiness as its goal… .

We need in this world a much better and clearer understanding of the worth of some things and of the worthlessness of others.

Rotary has demonstrated its ability to contribute toward the world’s supply of happiness by elevating business to a companionable standard. Most of us have to live pretty near to business and it is worth while to have taken a part in the great movements of the day tending toward the idealizing of trade. In this respect the advent of Rotary was particularly opportune. It has often seemed to me that we should stop there, lest our fire become too much scattered to be effective. At other more sanguine moments, it has seemed to me, in view of the heart that has evidenced itself in past endeavors, that it would not be presumptuous, were we to look the entire big job right in the face—Life itself, and rise to the task of undertaking its betterment.

If I improve my mode of living, my business will be very likely to be benefited. Many business successes are the direct consequence of right living, outside of business; and many business failures are directly traceable to wrong living. The business life and the home life are not independent of each other; they are interdependent, one upon the other.

We shall have a Rotarian good book some day, a sort of Rotarian bible; not a disconnected product of many and diverse minds, but a carefully evolved compendium of, not a Rotarian philosophy of the day, but of THE Rotarian philosophy of the day—not the Rotarian philosophy for all time to come, because Rotarian philosophy will always be progressive.

Chapter by chapter, I would love to see the great book built up, not rapidly. In my optimistic moments, I can see it take place among the foremost of the world’s productions of its kind. It will fill a long felt want. What a pleasure it will be when we really have something definite to show; when we can hand our book to a friend and say—“There, My Friend, within the covers of that book you will find all that Rotary holds dear. Read it, it will do you good.” “Not a Rotarian? Hush man, every one with the love of the world in his heart is a Rotarian; you mean that you are not a member of any Rotary Club; that is different.”

Source: Paul P. Harris, “Passing Our Tenth Milestone,” The Rotarian, February 1915: 15–16.

The little boy sat bolt upright and still in the rough wooden chair, but his mind was very busy.

This was his weekly hour of revolt.

The kindly lady who could never seem to find her glasses would have been terribly shocked if she had known what was going on inside the little boy’s mind.

“You must love Jesus,” she said every Sunday, “and God.”

The little boy did not say anything. He was afraid to say anything; he was almost afraid that something would happen to him because of the things he thought.

Love God? Who was always picking on people for having a good time and sending little boys to hell because they couldn’t do better in a world which he had made so hard! Why didn’t God take some one his own size?

Love Jesus! The little boy looked up at the picture which hung on the Sunday-school wall. It showed a pale young man with flabby forearms and a sad expression. The young man had red whiskers.

Then the little boy looked across to the other wall. There was Daniel, good old Daniel, standing off the lions. The little boy liked Daniel. He liked David, too, with the trusty sling that landed a stone square on the forehead of Goliath. And Moses, with his rod and his big brass snake. They were winners—those three. He wondered if David could whip Jeffries. Samson could! Say, that would have been a fight!

But Jesus! Jesus was the “lamb of God.” The little boy did not know what that meant, but it sounded like Mary’s little lamb. Something for girls—sissified. Jesus was also “meek and lowly,” a “man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.” He went around for three years telling people not to do things.

Sunday was Jesus’ day; it was wrong to feel comfortable or laugh on Sunday.

The little boy was glad when the superintendent rang the bell and announced, “We will now sing the closing hymn.” One more bad hour was over. For one more week the little boy had got rid of Jesus.

Years went by and the boy grew up and became a business man.

He began to wonder about Jesus.

He said to himself: “Only strong magnetic men inspire great enthusiasm and build great organizations. Yet Jesus built the greatest organization of all. It is extraordinary.”

The more sermons the man heard and the more books he read the more mystified he became.

One day he decided to wipe his mind clean of books and sermons.

He said, “I will read what the men who knew Jesus personally said about him. I will read about him as though he were a new historical character, about whom I had never heard anything at all.”

The man was amazed.

A physical weakling! Where did they get that idea? Jesus pushed a plane and swung an adze; he was a successful carpenter. He slept outdoors and spent his days walking around his favorite lake. His muscles were so strong that when he drove the money-changers out, nobody dared to oppose him!

A kill-joy! He was the most popular dinner guest in Jerusalem! The criticism which proper people made was that he spent too much time with publicans and sinners (very good fellows, on the whole, the man thought) and enjoyed society too much. They called him a “wine bibber and a gluttonous man.”

A failure! He picked up twelve men from the bottom ranks of business and forged them into an organization that conquered the world.

When the man had finished his reading he exclaimed, “This is a man nobody knows!”

“Some day,” said he, “someone will write a book about Jesus. Every businessman will read it and send it to his partners and his salesmen. For it will tell the story of the founder of modern business.” …

… Surely no one will consider us lacking in reverence if we say that every one of the “principles of modern salesmanship” on which businessmen so much pride themselves are brilliantly exemplified in Jesus’ talk and work… .

Jesus taught all this without ever teaching it. Every one of his conversations, every contact between his mind and others, is worthy of the attentive study of any sales manager. Passing along the shores of a lake one day, he saw two of the men whom he wanted as disciples. Their minds were in motion; their hands were busy with their nets; their conversation was about conditions in the fishing trade, and the prospects of a good market for the day’s catch. To have broken in on such thinking with the offer of employment as preachers of a new religion would have been to confuse them and invite a sure rebuff. What was Jesus’ approach?

“Come with me,” he said, “and I will make you fishers of men.”

Fishers … that was a word they could understand … fishers of men … that was a new idea… . what was he driving at … fishers of men … it sounded interesting … well, what is it, anyway?”

He sat on a hillside overlooking a fertile country. Many of the crowd who gathered around him were farmers with their wives and sons and daughters. He wanted their interest and attention; it was important to make them understand, at the very outset, that what he had to say was nothing vague or theoretical but of direct and immediate application to their daily lives.

“A sower went forth to sow,” he began, “and when he sowed some seeds fell by the wayside and the fowls came and devoured them up … ” Were they interested … were they? Every man of them had gone through that experience … the thievish crows … many a good day’s work they had spoiled… . So this Teacher knew something about the troubles that farmers had to put up with, did he? Fair enough … let’s hear what he has to say… . ”

… With his very first sentence he put himself in step with [his audience]; it was invariably a thought in line with their own thinking, easy for even the dullest to understand, and shrewdly calculated to awaken an appetite for more.

… On one occasion, you recall, he stated his recipe for success. It was on the afternoon when [apostles] James and John came to ask him what promotion they might expect. They were two of the most energetic of the lot, called “Sons of Thunder” by the rest, being noisy and always in the midst of some sort of a storm. They had joined the ranks because they liked him, but with no very definite idea of what it was all about; and now they wanted to know where the enterprise was heading, and just what there would be in it for them.

“Master, “they said, “we want to ask what plans you have in mind for us. You’re going to need big men around you when you establish your kingdom; our ambition is to sit on either side of you, one on your right hand and the other on your left.”

Who can object to that attitude? If a man fails to look after himself, certainly no one will look after him. If you want a big place, go ask for it. That’s the way to get ahead.

Jesus answered with a sentence which sounds poetically absurd.

“Whosoever will be great among you, shall be your minister,” he said, “and whosoever of you will be the chiefest, shall be servant of all.”

A fine piece of rhetoric, now isn’t it? Be a good servant and you will be great; be the best possible servant and you will occupy the highest possible place. Nice idealistic talk but utterly impractical; nothing to take seriously in a common sense world. That is just what most men thought for some hundreds of years, and then, quite suddenly, Business woke up to a great discovery. You will hear that discovery proclaimed in every sales convention as something distinctly modern and up to date. It is emblazoned in the advertising pages of every magazine.

Look through these pages.

Here is the advertisement of an automobile company, one of the greatest in the world. And why is it greatest? On what does it base its claim to leadership? On its huge factories and financial strength? They are never mentioned. On its army of workmen or its high salaried executives? You might read its advertisements for years without suspecting that it had either. No. “We are great because of our service,” the advertisements cry. “We will crawl under your car oftener and get our backs dirtier than any of our competitors. Drive up to our service stations and ask for anything at all—it will be granted cheerfully. We serve; therefore we grow.” …

So we have the main points of his business philosophy:

We have quoted some men of conspicuous success, but the same sound principles apply to every walk of life. Great progress will be made in the world when we rid ourselves of the idea that there is a difference between work and religious work. We have been taught that a man’s daily business activities are selfish, and that only the time which he devotes to church meetings and social service activities is consecrated. Ask any ten people what Jesus meant by his “Father’s business,” and nine of them will answer “preaching.” To interpret the words in this narrow sense is to lose the real significance of his life. It was not to preach that he came into the world, nor to teach, nor to heal. These are all departments of his Father’s business, but the business itself is far larger, more inclusive. For if human life has any significance, it is this—that God has set going here an experiment to which all His resources are committed. He seeks to develop perfect human beings, superior to circumstance, victorious over Fate. No single kind of human talent or effort can be spared if the experiment is to succeed. The race must be fed and clothed and housed and transported, as well as preached to, and taught and healed. Thus all business is his Father’s business. All work is worship, all useful service prayer. And whoever works wholeheartedly at any worthy calling is a co-worker with the Almighty in the great enterprise which He has initiated but which he can never finish without the help of men.

Source: Bruce Barton, The Man Nobody Knows, Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1925.

In the following book review, H. L. Mencken, writer, editor, and one of the era’s foremost cultural critics, explores the issue of “standardization” in American society. By “standardization,” Mencken effectively means conformity, one of the chief values that Babbitt espouses and that Sinclair Lewis makes clear is detrimental to the nation. Yet during the Jazz Age, Americans felt a tremendous pressure to conform to societal values and attitudes. A Red Scare early in the 1920s, associated with an influx of immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, and continued political and labor unrest not only in the United States but also in Europe caused people to fear for the stability of their lives, and the era’s rapid pace of change, which is always unsettling, prompted a retreat into old, familiar patterns of behavior and beliefs. Anyone unwilling to conform was looked upon with suspicion and distrust. When Babbitt flirts with socialist ideas, for instance, and associates with Zenith’s bohemian crowd, he soon finds himself ostracized from the city’s “Solid Citizens” and must pay the consequences for his rebellion by a decline in his business. In a nation that prides itself on independence, conformity was the reality of American culture during the Jazz Age. Mencken’s essay reinforces the lessons of Babbitt’s rebellion.

When, a few weeks ago, the clans gathered at Berlin to celebrate the sixth anniversary of the German republic, the prat or [sic] of the day reached the climax of his address in the following sentence:

“We must emancipate ourselves from the mad tendency to permit our national life to become Americanized!”

This remarkable declaration got relatively little attention in the American press; when it was mentioned at all, it was commonly with the declaration that the Germans are still suffering from war wounds, and envy our vast prosperity. But that, I think, was a shallow reading of it. The Germans, as a matter of fact, give very little attention to their war wounds, which, after all, were not fatal; they devote themselves mainly to looking ahead. And our prosperity does not greatly disturb them, for in it they see a guarantee of their own; what we are accomplishing today, with the odds all in our favor, they plan to do tomorrow, with the odds nearly even.

They are, in truth, quite as eager for the dollar as we are, and quite as determined to get it, by fair means or foul. That quest, so nearly universal in the modern world, is not what they have in mind when they speak of the dangers of Americanization. What they think of is something different. It may be described, in general, as the decay of spiritual values that has gone on among us during the past two generations. It may be described, in particular, as our growing impatience with the free play of ideas, our increasing tendency to reduce all virtues to the single one of conformity, our relentless and all pervading standardization. This is what all Europe fears when it contemplates the growing importance and influence of the United States. It hasn’t J. P. Morgan in mind, nor even General Pershing; it has Henry Ford. By Americanization it means Fordization—and not only in industry, but also in politics, art and even religion.

If you want to see how the United States of today looks to a reflective European you can do no better than get a little book called “Americanization; A World Menace,” written by W. T. Colyer… .

… Mr. Colyer is not blind to what we have accomplished. He sees a wilderness broken to the plow and the flivver. But, he sees also a people broken to the yoke.

It is the merciless ironing out of the individual, indeed, that chiefly arrests his attention, and he offers it as a solemn warning to his own countrymen. Americans have got on in the world, he says, by the simple process of sacrificing everything else to getting on. They began as a nation by setting up a table of inalienable human rights, but one by one those rights have gone by the board. No other nation of today is so rigorously policed. The lust to standardize and regulate extends to the most trivial minutae of private life.

It goes even further, passing beyond acts to thoughts. Such and such an idea is virtuous and “American;” its contrary is full of sin. Mr. Colyer believes that that principle is intolerably dangerous—that it is bound, in the long run, to throttle all intelligence and make for a groveling and ignominious stupidity. More, he believes the people of the United States have already made some progress along that depressing way.

… Europe sees Americanism, in brief, as a sort of Philistine uprising against the free spirit of man—as a conspiracy of dull and unimaginative men, fortuitously made powerful, against all the ideas and ideals that seem sound to their betters. Henry Ford, with his discovery that history is bunk and science a fraud, seems to it to be the archetypical American. He is, within his own field, a man of great energy and very respectable talents. He has done useful work, and perhaps earned at least a part of his immense reward. But he insists upon leaving his own field for fields that are strange and impenetrable to him, and upon laying down laws therein for the government of their natural inhabitants. This is what Europe understands by Americanism, by Americanization. And this is what it fears.

The trial of the infidel Scopes, I believe, greatly added to those fears. It got more space in the European papers than the election of Coolidge, even more than the death of Harding. They gave it the place of honor for days running. And what was the lesson that they deducted from it? First, that all ordinary intellectual decency had departed from the American people—that they were willing and even eager to flaunt their contempt for all sound knowledge and sound sense before the world. Second, that a nation cherishing such notions and feelings, and with the money and men to enforce them, deserved to be watched very carefully.

Europe hears relatively little about what is being done, often against cruel difficulties, by American artists and scientists, philosophers and publicists. It has its own supply of such men, and it naturally heeds them first. They have a high position over there, unmatched on this side of the ocean… . We put such men much lower, and so we have fewer of them, and Europe, having more and better ones at home, hears little about the few we have. But Europe has no Henry Fords, or William Jennings Bryans, or Gimlet-Eye Butlers, or Major Hylans, or Wilbur Volivas, and so it is interested by them, instantly and hugely, when they appear in America. It observes that the American people, or, at all events, the great majority of the American people, take them quite seriously, and it concludes, not without reason, that they accurately represent America. It hears that Bryan was thrice within reach of the White House—and then it hears of him denouncing the theory that man is a mammal. It hears that Butler is an officer wearing the American uniform—and then it hears he is engaged in monkey shines to entertain the Anti-Saloon league. It hears that Ford is the richest man of a country in which riches exceed any other worth—and then it hears him reviling learning like a yokel in a cross roads grocery store.

Such phenomena surprise it—and shock it. They violate all notions of propriety, of decency. It cannot imagine a civilized people suffering them without immediate and angry rebellion. So it concludes that the Americans, despite their vast success in collaring dollars, have yet to go some distance before they are fully civilized. And when it hears talk of Americanization it shivers.

Source: H. L. Mencken, “Knowledge in Contempt in America, Believe Europeans,” Chicago Tribune, August 30, 1925.

Allen, Frederick Lewis. Only Yesterday. An Informal History of the 1920s. 1931. New York: Harper Perennial, 1964.

Calder, Lendol G. Financing the American Dream: A Cultural History of Consumer Credit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Curnutt, Kirk. “Fitzgerald’s Consumer World.” In A Historical Guide to F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Ed. Kirk Curnutt. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2004: 85–128.

Dooley, D. J. The Art of Sinclair Lewis. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1967.

Dumenil, Lynn. The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s. New York: Hill and Wang, 1995.

Ewen, Stuart. All Consuming Images: The Politics of Style in Contemporary Culture. New York: Basic, 1988.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Crack-Up. Ed. Edmund Wilson. New York: New Directions, 1945.

Gidlow, Liette. The Big Vote: Gender, Consumer Culture, and the Politics of Exclusion. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

Glickman, Lawrence B. “Rethinking Politics: Consumers and the Public Good in the ‘Jazz Age.’ ” OAH Magazine of History 21.3(2007): 16–20.

Grebstein, Sheldon Norman. Sinclair Lewis. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1962.

Hutchisson, James M. The Rise of Sinclair Lewis, 1920–1930. State College: Penn State University Press, 2001.

Lewis, Sinclair. Babbitt. 1922. New York: Bantam Classics, 1998.

Light, Martin. The Quixotic Vision of Sinclair Lewis. Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1975.

Lingeman, Richard. Sinclair Lewis: Rebel from Main Street. New York: Random House, 2002.

Marchand, Roland. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920–1940. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

Maxwell, Lauren Rule. “Consumer Culture and Advertising.” In F. Scott Fitzgerald in Context. Ed. Bryant Mangum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013: 311–320.

Mencken, H. L. “Portrait of an American Citizen.” The Smart Set 69(October 1922): 138–139.

Olney, Martha L. “Advertising, Consumer Credit, and the ‘Consumer Durables Revolution’ of the 1920s.” Journal of Economic History 47.2(1987): 489–491.

Olney, Martha L. Buy Now, Pay Later: Advertising, Credit, and Consumer Durables in the 1920s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Parrish, Michael E. Anxious Decades: America in Prosperity and Depression, 1920–1941. New York: Norton, 1992.

Schorer, Mark. Sinclair Lewis: An American Life. New York: McGraw- Hill, 1961.

Schorer, Mark, ed. Sinclair Lewis: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1962.

Vidal, Gore. “The Romance of Sinclair Lewis.” The New York Review of Books, October 8, 1992.