CONCERNING THE ‘OUR FATHER’

This paper which was written in Ardèche, or immediately after Simone’s stay at Gustave Thibon’s house, corresponds with the discovery of the ‘Our Father’ which she had just made in the course of the summer, as related in Letter IV.

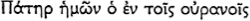

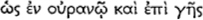

‘Our Father who art in Heaven.’

He is our Father. There is nothing real in us which does not come from him. We belong to him. He loves us, since he loves himself and we are his. Nevertheless he is our Father who is in heaven—not elsewhere. If we think to have a Father here below it is not he, it is a false God. We cannot take a single step towards him. We do not walk vertically. We can only turn our eyes towards him. We do not have to search for him, we only have to change the direction in which we are looking. It is for him to search for us. We must be happy in the knowledge that he is infinitely beyond our reach. Thus we can be certain that the evil in us, even if it overwhelms our whole being, in no way sullies the divine purity, bliss and perfection.

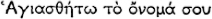

‘Hallowed be thy Name’

God alone has the power to name himself. His name is un-pronounceable for human lips. His name is his word. It is the Word of God. The name of any being is an intermediary between the human spirit and that being, it is the only means by which the human spirit can conceive something about a being that is absent. God is absent. He is in heaven. Man’s only possibility of gaining access to him is through. his name. It is the Mediator. Man has access to this name, although it also is transcendent. It shines in the beauty and order of the world and it shines in the interior light of the human soul. This name is holiness itself; there is no holiness outside it; it does not therefore have to be hallowed. In asking for its hallowing we are asking for something which exists eternally, with full and complete reality, so that we can neither increase nor diminish it, even by an infinitesimal fraction. To ask for that which exists, that which exists really, infallibly, eternally, quite independently of our prayer, that is the perfect petition. We cannot prevent ourselves from desiring; we are made of desire; but the desire which nails us down to what is imaginary, temporal, selfish, can, if we make it pass wholly into this petition, become a lever which will tear us from the imaginary into the real and from time into eternity, and will lift us right out of the prison of self.

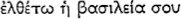

‘Thy Kingdom Come.’

This concerns something to be achieved, something not yet here. The Kingdom of God means the complete filling of the entire soul of intelligent creatures with the Holy Spirit. The Spirit bloweth where he listeth? We can only invite him. We must not even try to invite him in a definite and special way to visit us or anyone else in particular, or even everybody in general; we must just invite him purely and simply, so that our thought of him is an invitation, a longing cry. It is as when one is in extreme thirst, ill with thirst; then one no longer thinks of the act of drinking in relation to oneself, nor even of the act of drinking in a general way. One merely thinks of water, actual water itself, but the image of water is like a cry from our whole being.

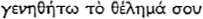

‘Thy will be done!

We are only absolutely, infallibly certain of the will of God concerning the past. Everything which has happened, whatever it may be, is in accordance with the will of the almighty Father. That is implied by the notion of almighty power. The future also, whatever it may contain, once it has come about, will have come about in conformity with the will of God. We can neither add to nor take from this conformity. In this clause, therefore, after an upsurging of our desire towards the possible, we are once again asking for that which is. Here, however, we are not concerned with an eternal reality such as the holiness of the Word, but with what happens in the time order. Nevertheless we are asking for the infallible and eternal conformity of everything in time with the will of God. After having, in our first petition, torn our desire away from time in order to fix it upon eternity, thereby transforming it, we return to this desire which has itself become in some measure eternal, in order to apply it once more to time. Whereupon our desire pierces through time to find eternity behind it. That is what comes about when we know how to make every accomplished fact, whatever it may be, an object of desire. We have here quite a different thing from resignation. Even the word acceptance is too weak. We have to desire that everything which has happened should have happened, and nothing else. We have to do so, not because what has happened is good in our eyes, but because God has permitted it, and because the obedience of the course of events to God is in itself an absolute good.

‘On earth as it is in heaven.’

The association of our desire with the almighty will of God should be extended to spiritual things. Our own spiritual ascents and falls, and those of the beings we love, have to do with the other world, but they are also events which take place here below, in time. On that account they are details in the immense sea of events and are tossed about with the ocean in a way which conforms to the will of God. Since our failures of the past have come about, we have to desire that they should have come about. We have to extend this desire into the future, for the day when it will have become the past. It is a necessary correction of the petition that the kingdom of God should come. We have to cast aside all other desires for the sake of our desire for eternal life, but we should desire eternal life itself with renunciation. We must not even become attached to detachment. Attachment to salvation is even more dangerous than the others. We have to think of eternal life as one thinks of water when dying of thirst, and yet at the same time we have to desire that we and our loved ones should be eternally deprived of this water rather than receive it in abundance in spite of God’s will, if such a thing were conceivable.

The three foregoing petitions are related to the three Persons of the Trinity, the Son, the Spirit, and the Father, and also to the three divisions of time, the present, the future and the past. The three petitions which follow have a more direct bearing on the three divisions of time, and take them in a different order; present, past and future.

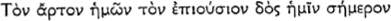

‘Give us this day our daily bread,’ [the bread which is supernatural.]

Christ is our bread. We can only ask to have him now. Actually he is always there at the door of our souls, wanting to enter in, though he does not force our consent. If we agree to his entry, he enters; directly we cease to want him, he is gone. We cannot bind our will today for tomorrow, we cannot make a pact with him that tomorrow he will be within us, even in spite of ourselves. Our consent to his presence is the same as his presence. Consent is an act, it can only be actual, that is to say in the present. We have not been given a will which can be applied to the future. Everything which is not effective in our will is imaginary. The effective part of the will has its effect at once, its effectiveness cannot be separated from itself. The effective part of the will is not effort, which is directed towards the future. It is consent, it is the ‘yes’ of marriage. A ‘yes’ pronounced within the present moment and for the present moment, but spoken as an eternal word, for it is consent to the union of Christ with the eternal part of our soul.

Bread is a necessity for us. We are beings who continually draw our energy from outside, for as we receive it we use it up in effort. If our energy is not daily renewed, we become feeble and incapable of movement. Besides actual food, in the literal sense of the word, all incentives are sources of energy for us. Money, ambition, consideration, decorations, celebrity, power, our loved ones, everything which puts into us the capacity for action is like bread. If anyone of these attachments penetrates deeply enough into us to reach the vital roots of our carnal existence, its loss may break us and even cause our death. That is called dying of love. It is like dying of hunger. All these objects of attachment go together with food, in the ordinary sense of the word, to make up the daily bread of this world. It depends entirely on circumstances whether we have it or not. We should ask nothing with regard to circumstances unless it be that they may conform to the will of God. We should not ask for earthly bread.

There is a transcendant energy whose source is in heaven, and this flows into us as soon as we wish for it. It is a real energy; it performs actions through the agency of our souls and of our bodies.

We should ask for this food. At the moment of asking, and by the very fact that we ask for it, we know that God will give it to us. We ought not to be able to bear to go without it for a single day, for when our actions only depend on earthly energies, subject to the necessity of this world, we are incapable of thinking and doing anything but evil. God saw ‘that the misdeeds of man were multiplied on the earth and that all the thoughts of his heart were continually bent upon evil.’ 1 The necessity which drives us towards evil governs everything in us except the energy from on high at the moment when it comes into us. We cannot store it.

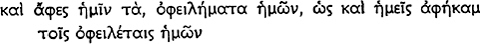

‘And forgive us our debts, as we also forgive our debtors.’

At the moment of saying these words we must have already remitted everything that is owing to us. This not only includes reparation for any wrongs we think we have suffered, but also gratitude for the good we think we have done, and it applies in a quite general way to all we expect from people and things, to all we consider as our due and without which we should feel ourselves to have been frustrated. All these are the rights which we think the past has given us over the future. First there is the right to a certain permanence. When we have enjoyed something for a long time, we think that it is ours, and that we are entitled to expect fate to let us go on enjoying it. Then there is the right to a compensation for every effort whatever its nature, be it work, suffering or desire. Every time that we put forth some effort and the equivalent of this effort does not come back to us in the form of some visible fruit, we have a sense of false balance and emptiness which makes us think that we have been cheated. The effort of suffering from some offence causes us to expect the punishment or apologies of the offender, the effort of doing good makes us expect the gratitude of the person we have helped, but these are only particular cases of a universal law of the soul. Every time we give anything out we have an absolute need that at least the equivalent should come into us, and because we need this we think we have a right to it. Our debtors comprise all beings and all things; they are the entire universe. We think we have claims everywhere. In every claim which we think we possess there is always the idea of an imaginary claim of the past on the future. That is the claim which we have to renounce.

To have forgiven our debtors is to have renounced the whole of the past in a lump. It is to accept that the future should still be virgin and intact, strictly united to the past by bonds which are unknown to us, but quite free from the bonds which our imagination thought to impose upon it. It means that we accept the possibility that no matter what may happen, and that it may happen to us in particular; it means that we are prepared for the future to render all our past life sterile and vain.

In renouncing at one stroke all the fruits of the past without exception, we can ask of God that our past sins may not bear their miserable fruits of evil and error. So long as we cling to the past, God himself cannot stop this horrible fruiting. We cannot hold on to the past without retaining our crimes, for we are unaware of what is most essentially bad in us.

The principal claim which we think we have on the universe is that our personality should continue. This claim implies all the others. The instinct of self-preservation makes us feel this continuation to be a necessity, and we believe that a necessity is a right. We are like the beggar who said to Talleyrand: ‘Sir, I must live,’ and to whom Talleyrand replied. ‘I do not see the necessity for that.’ Our personality is entirely dependent on external circumstances which have unlimited power to crush it. But we would rather die than admit this. From our point of view the equilibrium of the world is a combination of circumstances so ordered that our personality remains intact and seems to belong to us. All the circumstances of the past which have wounded our personality appear to us to be disturbances of balance which should infallibly be made up for one day or another by phenomena having a contrary effect. We live on the expectation of these compensations. The near approach of death is horrible chiefly because it forces the knowledge upon us that these compensations will never come.

To remit debts is to renounce our own personality. It means that we renounce everything which goes to make up our ego, without any exception. It means knowing that in the ego there is nothing whatever, no psychological element, which external circumstances could not do away with. It means accepting that truth. It means being happy that things should be so.

The words ‘Thy will be done’ imply this acceptance, if we say them with all our soul. That is why we can say a few moments later: ‘We forgive our debtors.’

The forgiveness of debts is spiritual poverty, spiritual nakedness, death. If we accept death completely, we can ask God to make us live again, purified from the evil which is in us. For to ask him to forgive us our debts is to ask him to wipe out the evil which is in us. Pardon is purification. God himself has not the power to forgive the evil in us while it remains there. God will have forgiven our debts when he has brought us to the state of perfection.

Until then God forgives our debts partially in the same measure as we forgive our debtors.

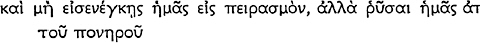

‘And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.’

The only temptation for man is to be abandoned to his own resources in the presence of evil. His nothingness is then proved experimentally. Although the soul has received supernatural bread at the moment when it asked for it, its joy is mixed with fear because it could only ask for it for the present. The future is still to be feared. The soul has not the right to ask for bread for the morrow, but it expresses its fear in the form of a supplication. It finishes with that. The prayer began with the word ‘Father,’ it ends with the word ‘evil.’ We must go from confidence to fear. Confidence alone can give us strength enough not to fall as a result of fear. After having contemplated the name, the kingdom and the will of God, after having received the supernatural bread and having been purified from evil, the soul is ready for that true humility which crowns all virtues. Humility consists of knowing that in this world the whole soul, not only what we term the ego in its totality, but also the supernatural part of the soul which is God present in it, is subject to time and to the vicissitudes of change. There must be absolute acceptance of the possibility that everything which is natural in us should be destroyed. But we must simultaneously accept and repudiate the possibility that the super-natural part of the soul should disappear. It must be accepted as an event which would only come about in conformity with the will of God. It must be repudiated as being something utterly horrible. We must be afraid of it, but our fear must be as it were the completion of confidence.

The six petitions correspond with each other in pairs. The bread which is transcendant is the same thing as the divine name. It is what brings about the contact of man with God. The kingdom of God is the same thing as his protection stretched over us against temptation; to protect is the function of royalty. Forgiving our debtors their debts is the same thing as the total acceptance of the will of God. The difference is that in the first three petitions the attention is fixed solely on God. In the three last, we turn our attention back to ourselves in order to compel ourselves to make these petitions a real and not an imaginary act.

In the first half of the prayer, we begin with acceptance. Then we allow ourselves a desire. Then we correct it by coming back to acceptance. In the second half, the order is changed; we finish by expressing desire. Only desire has now become negative; it is expressed as a fear; therefore it corresponds to the highest degree of humility and that is a fitting way to end.

The Our Father contains all possible petitions; we cannot conceive of any prayer which is not already contained in it. It is to prayer what Christ is to humanity. It is impossible to say it once through, giving the fullest possible attention to each word, without a change, infinitesimal perhaps but real, taking place in the soul.

1 Genesis vi, 5.