Yuri Leving

In 1958, despite his well-known reluctance to autograph his own books, Nabokov gladly signed a copy of Lolita for Mrs. Anita Loos.1 Loos was not the average autograph-seeker: She herself was an acclaimed writer, having authored a runaway bestseller, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, in 1925, the same year Nabokov published his debut novel, Mary. A musical-film version of Loos’s book, starring Marilyn Monroe, was produced in 1953. Loos believed that Monroe was an inspired casting. It is difficult to say for sure what Nabokov thought about the iconic blonde or whether he would have approved of her as Hugh Hefner’s choice for the inaugural cover of Playboy (a magazine he read with pleasure beginning in the early 1960s), but the look of his cover girl certainly mattered for Nabokov.2

How should Lolita, the heroine of Nabokov’s most cherished novel, appear? Is there a precise description of her look anywhere in the novel? Why is her visual representation important? In partial answer to this last question, we should begin by acknowledging that the jacket manipulates the reader’s perception: The cover picture, as Peter Sinnema argues, affects the reader not only at the time of purchase but also during the process of reading.3 These and other questions naturally lead to more fundamental issues concerning the visual design and the politics of illustrating Nabokov’s Lolita; however, for the purposes of the present chapter, I will limit the discussion to the visual aspects of the novel’s marketing strategies as treated specifically by Russian publishers during the past two decades. Using materials from my personal collection—close to thirty Russian-language editions of Nabokov’s novel—I trace the most important stages in the evolution of Lolita’s visual representation in Russia. This study explores how Lolita was commercialized for post-Soviet audiences; it also touches upon some aesthetic differences between the Russian and American versions of the text, and the branding of the Russian Lolita (1).

1. St. Petersburg: Azbooka-klassika, 2009. [Design by Ilya Kuchma and Vadim Pozhidaev. 415 pp., 7,000 copies; hardcover.] Unless otherwise noted, all books shown in this chapter are editions of Lolita.

Most of the cover art decorating Nabokov’s cult novel in the Soviet Union and Russia has hardly been original; it usually has relied on borrowed paintings or photographs with unclear provenance, and the logic of the selections is not always immediately apparent. The visual treatments of Lolita in Russia can be classified into four distinct groups.

The first category consists of direct reproductions of existing works of art. The common denominator of these cover images is the depiction of a young girl, often in a seductive pose or with an intense gaze directed at the reader. As the understanding of Nabokov and his prose evolved in Russia, publishers adapted to attract new potential audiences, often envisioned as refined connoisseurs of an intricate but frolicsome prose. Consequently, book designers opted for imagery that middle-class consumers of mass culture would be familiar with through postcards and office-poster art, such as clichéd works by Gustav Klimt or Edgar Degas.

The second category appeals to an indiscriminate audience, as it triggers the latent erotic messages embedded in the novel. These covers feature seminude or topless models who look approximately the age of the title heroine; that is to say, barely legal.

The third category absorbs and capitalizes on the success of the latest screen adaptation of Lolita, by Adrian Lyne. Publishers rely on the recognizable faces of the two lead actors, thus ensuring that buyers readily establish a connection to a product that has already been widely distributed and received its portion of succès de scandale.

The final, and rarest, category comprises cover art that attempts to employ an original artistic work. This is something less typical for Lolita editions published by the post-Soviet book industry, and primarily manifests as illustrations inside the book rather than on its cover.

At the core of Lolita’s plot is a girl with a graphic (pun intended) biography and face. This sensational, if not sensual, quality has continued to resonate with reading audiences ever since the book’s publication. As a result, Nabokov belongs to both the American and Russian literary canons. However, while much has been written about Lolita’s Western cover design and public reception, the Russian book market’s relationship with Lolita has yet to be analyzed.4 Prior to examining specific examples and illustrations, a few general remarks will help contextualize the problem.

The long-standing connection between covers and marketing is a topic that has come to scholarly attention only fairly recently.5 Contemporary critics argue that book covers are instrumental in shaping the response of readers, markets, and booksellers to the texts within them. In the nineteenth century, if not even earlier, styles of bindings, fonts, and cover illustrations influenced the allocation of cultural value to literary works and helped to shape the popularity of those texts.6 Covers enjoyed even greater influence over book sales after the 1820s, when publishers began to employ cloth bindings that were both cheaper and more easily decorated than leather. Even at this early stage, covers were sometimes used for advertising purposes.7 Some dust jackets, for example, originally conceived as entirely disposable and minimally decorative protective devices, were also used for marketing, although this was not consistently done until the 1890s.8 As Nicole Matthews points out, “If jackets and covers had a role to play in the marketing of books during the nineteenth century, they came to have new forms of significance in the twentieth. Undoubtedly one of the critical shifts in the marketing of books in the twentieth century was the development of the paperback.”9

Even before becoming a bestselling author, Nabokov was genuinely interested in the promotional aspects of publishing his own works. Lolita is a near-ideal case study to test how he balanced concepts of successful market campaigning with his own well-known high demands for ethics and aesthetics in the field of literary production. When Lolita appeared on the literary market during the 1950s, bookshops “were changing their displays such that the front covers, rather than simply book spines, were visible to the browser. Publishers labored to encourage booksellers to display their releases with the appealing front covers clearly visible.”10 Moreover, publishers devoted “significant portions of their promotion budget to shelving which would enable arresting displays of the front covers of their own publications.”11 Nabokov was keenly aware of this trend and attempted to influence the design of his books, especially Lolita. “A hasty piece of cover art might mislead a reader to imagine Dolores Haze as a platinum blond or, at worst, steer a reader away from a book,” writes Paul Maliszewski, insisting that illustration demands “that artists create a pictorial representation of a book; translating words into an image. . . . Both cover artist and translator had to be responsible to and respectful of the original book.”12

In September 1955 Lolita was published in France in the now-famous plain green paperback. After reviewing a few proposed designs for Putnam’s first American hardcover edition of Lolita, Nabokov demanded that no girls be featured on it:13

Who would be capable of creating a romantic, delicately drawn, non-Freudian and non-juvenile, picture of LOLITA (a dissolving remoteness, a soft American landscape, a nostalgic highway— that sort of thing)? There is one subject which I am emphatically opposed to: any kind of representation of a little girl.14

The first American edition, issued in August 1958, bore no images at all (2). Weidenfeld and Nicolson followed suit in 1959 with the same modest cover, featuring only the author’s name and the novel’s title. Around the same time, Nabokov instructed Walter Minton, “If we cannot find that kind of artistic and virile painting”—referring to “melting clouds” and a “receding road”—“let us settle for an immaculate white jacket (rough texture paper instead of the usual glossy kind), with LOLITA in bold black lettering.”15 This raises a question: Why did Nabokov—who was concerned with how his writing was being marketed, at a time when prevailing promotional strategies favored the clear visibility of front covers—insist in this instance on the most minimalist solution possible, “bold black lettering”? To keep Nabokov’s request in perspective, one should recall the cultural context, especially the realities of the literary market of the period. The Penguin Books trend of purely typographic covers was firmly established in the mid-1950s. This was in stark contrast to the general practice of publishers in the United States. In America the lurid cover was “considered essential for securing mass sales of paper backed books.” It had often been suggested that Penguin might succeed commercially if it conformed to this general practice, but “the decision [had] been made, as a matter of taste, to reject the American kind of cover.”16 Penguin instead maintained a lucid and restrained typography: the house’s early look implied high literacy but low graphic response in the reader. As Adrian Wilson asked, “when every vivid paperback cover is outscreaming its neighbor, might not the greatest impact be made by the severely reticent?”17

2. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1958. [Hardcover.]

Nabokov obviously wanted to draw a line between highbrow and lowbrow products, and before Lolita was issued in paperback—a medium that was still strongly associated with crime fiction and modern romance dramas18—he wanted the book’s artistic and literary merits to achieve recognition. Hence, the “Penguin paradox” possibly served as one of his early marketing models. To be sure, starting in the early 1960s Nabokov stopped objecting to pictorial depictions of Lolita on the front covers of international editions of the novel (except the Russian ones), and amusingly commented on the designers’ and publishers’ incongruities or blunt goofs.19 Nabokov allowed this partially out of growing frustration but probably also because he felt he had achieved his initial objective.

The history of Lolita in Russia is mainly a story of curiosities. Firmly believing that there was no one capable of adequately translating his most precious English novel, Nabokov decided to personally take on the task of adapting his American masterpiece to his “docile” native language.20 His own Russian translation of Lolita was published in 1967, twelve years after the book’s maiden voyage, in English, and twenty years before his official comeback in his native land.

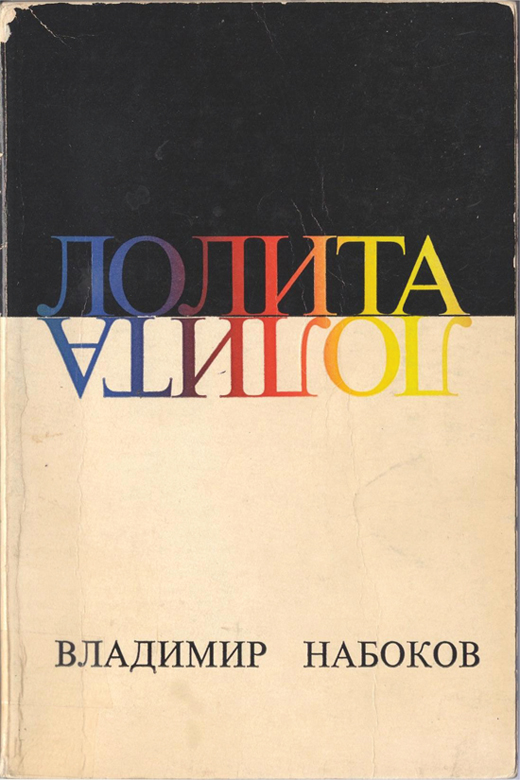

While Nabokov could ensure the best possible quality of translation, exercising actual power over the packaging turned out to be more difficult. Even in the West, Nabokov’s control of the cover imagery rarely extended to the American paperbacks (with the exception of the Parisian Olympia and first several U.S. editions). At a time when all English- and foreign-language publications of the novel were adorned with girls of every type, the two early Russian Lolitas were striking for their modest appearance. At Nabokov’s insistence, the émigré Russian versions offered plain letters: black-on-white (3) and a rainbow-colored title with its reflection (a reversed mirror-image) on the New York edition issued by Phaedra Publishers (4).

3. Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1976. [Second Russian edition of the novel; second printing. 304 pp., paper.]

4. New York: Phaedra Publishers, 1967. [304 pp., paper.]

In the years during and immediately after the Khrushchev thaw, Nabokov hoped to broaden his Russian-language readership beyond the émigré audience, possibly counting on Soviet readers as well. In fact, fans of the banned author had already obtained xeroxed copies of the book and had smuggled them into the USSR; such samizdat circulation of Nabokov’s writings perhaps explains Nabokov’s insistence on publishing more copies of Lolita in Russian even as the Phaedra edition was selling poorly (some of the naturalized Russian Americans could also read his novel in the original English). At a certain point Nabokov even tried to interest Grove Press in a joint publication of the Russian edition with Phaedra, which needed an influx of $5,000 to continue the advertising campaign and to add more copies to the 5,000 Russian-language jackets that were printed initially.21

Nabokov’s novel was not released in Russia until 1989, in what was still the USSR. During that critical year, the total print run of three separate publications of the novel amounted to 600,000 copies. Russian publishers printed twice as many Lolitas in 1990 and 1991.22 The highest one-time print run of Lolita in Russia was half a million;23 the smallest, a “mere” hundred thousand copies. The landing party of Nabokov’s previously outlawed novel was evenly distributed across the Russian-speaking empire under the official rule of the Communist Party: In 1991, the book came out privately in cities ranging from Moscow and Kazan to provincial Voronezh, from the southern town of Krasnodar to the large industrial port of Khabarovsk in Russia’s Far East. Compare these stunning figures with those of a typical Russian book of the late 1990s, when a standard print run of such a commercially low-risk enterprise like Lolita would be no more than 5,000–7,000 copies. With almost three million copies sold in Russia during 1990 and ’91 alone, Nabokov’s Lolita became a national bestseller in the late writer’s home.

Even after the socialist publishing system collapsed along with the state that supported it, the novel was aggressively sold in paperback in response to readers’ unprecedented demand. Lolita was published in post-Soviet Russia by book pirates of all stripes, from small local hackers to big publishing cooperatives. This business naturally thrived without any consent on the part of Vladimir Nabokov’s estate. In the virtual absence of control by Nabokov’s heirs or any self-restraining ethical considerations (not to mention the abandoned mechanisms of censorship), Nabokov’s serious and tragic novel was sold under the “pulp-fiction” category, mostly as paperbacks placed on shelves alongside fantasy works and detective fiction. A consequence of this temporary anarchy was the inauspicious shaping of the book’s reception: The Russian readership during the last decade of the twentieth century mainly perceived Lolita as a semierotic thriller. The early publishing entrepreneurs in Russia issued numerous sleek editions of Lolita to appeal to the mass readership, hungry for former “forbidden fruits.” In an unregulated market, such books were frequently misidentified as frivolous fiction (if not hardcore pornography) or mistaken for dissident anti-Soviet émigré pamphlets (such as those by Alexander Solzhenitsyn or Vladimir Voinovich). Nabokov’s writings were neither.

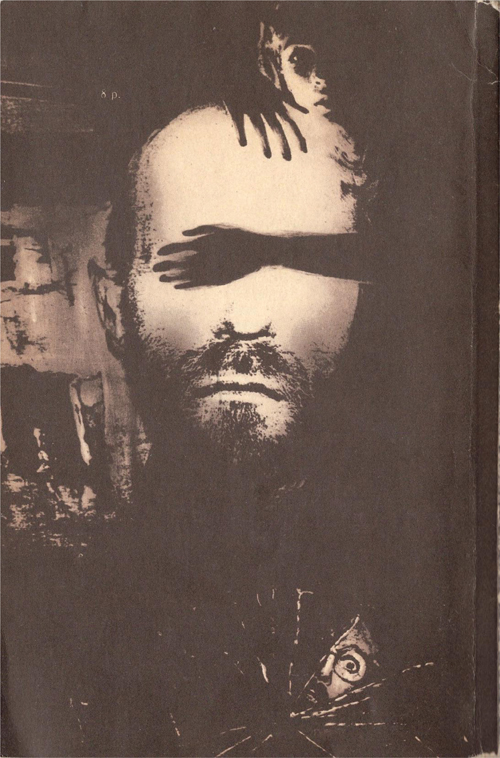

How did the state of affairs of a publishing industry in disarray affect how Nabokov’s novel was visually conveyed? The early days of Lolita in Russia proved to be somewhat artistically fruitful: ideas were daring and inventive, but execution was often poor. Many of the creative solutions for a cover design inevitably resulted from the limitations in polygraph printing technologies of struggling postsocialist publishers, but this unintentional austerity, ironically, often came closest to Nabokov’s original vision as expressed to his American publishers.

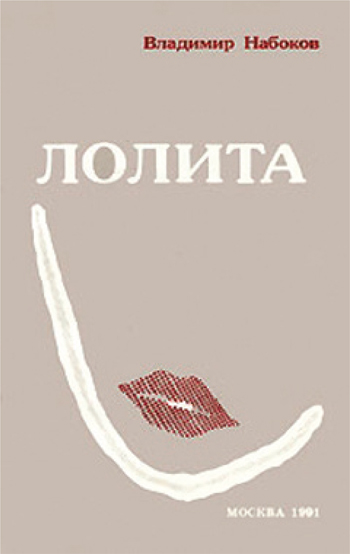

Several of the earliest post-Soviet editions’ designs are grim but remarkable and retain a degree of mystery, which Nabokov probably would have appreciated. In the beginning, the Russian Lolita only had a hint of a face—the back of her head—and a gown unbuttoned from behind. This 1990 edition of the novel features a contrast silhouette against an oppressing, empty black background (5).

5. Vladimir Nabokov. Lolita. Leningrad: Smart, Perspektiva, 1990. [318 pp., 100,000 copies, paperback.]

While this edition conceals Lolita’s face, it emphasizes her name. A simple font chosen for the title features a disproportionately enlarged letter o: the circle of perfection, and the vortex of misery and all-consuming passion. The girl leans her head forward slightly, exposing a vulnerable neck; the upper part of her dress is reminiscent of a hospital gown, which might suggest either the central scene of the novel at the Elphinstone facility or, once again, Lolita as a victim of the predator protagonist. The cover concept serves, therefore, as a kind of invitation to a beheading of a character who suffers physically and emotionally; it invites readers, faced with the difficult moral dilemmas of the novel, to suffer with Lolita.

The 1991 Lesinvest edition’s flowery cover (6) ironically echoes both its publishing firm’s name (literally translated from the Russian, it is “investor in a forest”) and the novel’s enchanted hunters motif. It depicts a seminaked forest nymph playing a trumpet.

6. Krasnodar: Lesinvest, LTD, 1991. [304 pp., 84,100 copies, paper.]

The title font evokes the chic prerevolutionary publications produced by the Russian Silver Age journal The World of Art (Mir Iskusstva) or, later, by the Leningrad-Moscow publisher Academia in the 1920s and ’30s. This Lolita is completely out of tune with the ordinary look of an American teenage girl. Instead, the cover offers something closer to a mythopoetic incarnation of her spirit from Clare Quilty’s play, in which Lolita performs the role of the farmer’s daughter confronting the poet.

Another 1991 edition features only an oval contour of one half of Lolita’s face (7); compare this with a similar technique used fifteen years later for a Russian Lolita cover (8). The later edition deploys the same minimalist outline technique but applies it to the naked body instead of to the face. This shift reflects the audacity—if not the indecency—of the twenty-first century’s approach to visually challenging illustration.

7. Moscow: ANS-Print, 1991. [256 pp., 500,000 copies; paper.]

8. St. Petersburg: Azbooka-klassika, 2006. [447 pp., 7,000 copies; hardcover.]

The 2006 cover, with a figurine in black ink line, was released by the Azbooka publishing house. Since the early 2000s the same publisher has held the official Russian publication rights to Nabokov. In the span between these two covers, Russian consumers had seen a score of much more offensive images. However, the laconic suggestiveness of the early days of the émigré and Russian Lolita editions seems to be gradually returning. It is likely that this will be the case as long as copyright control over Nabokov’s writings continues to be managed by the Nabokov estate and its legal representatives in Russia, or unless the sales of his books drop dramatically, forcing the publisher to reinvigorate the market with stimulating covers once again.

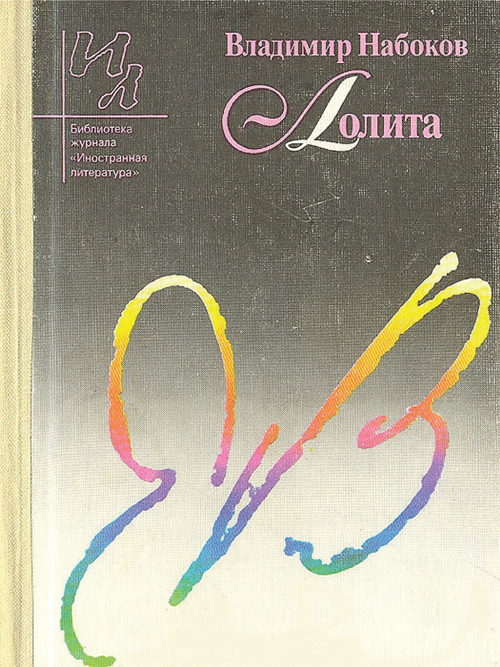

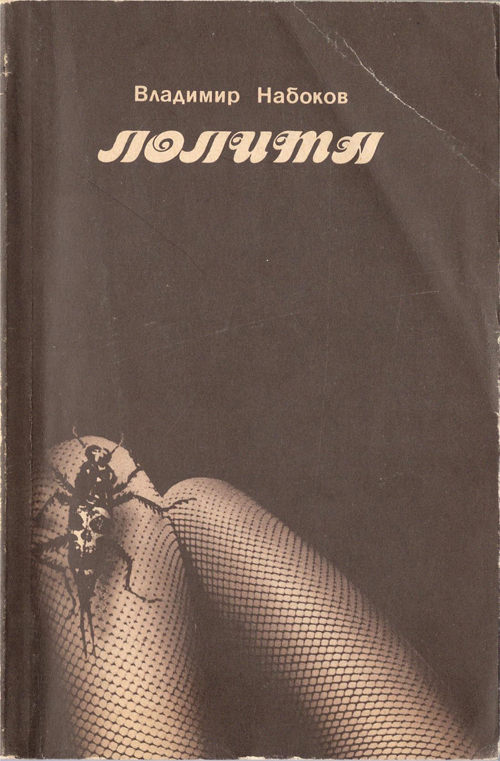

Many interesting black-and-white issues of Lolita appeared during the collapse of the Soviet Union. A dark-green hardcover edition offers elegant calligraphy in the novel’s title (9); the same calligraphic approach is featured in other cover art of the same period, either as an abstract graphic sketch (10) or by rendering Nabokov’s initials in such a way that they resemble a butterfly (11 and 12). A softcover (13 and 14) depicts a metaphoric entrapment of Lolita, whose unseen body and face are suggested by a pair of legs in fishnet nylons. The cover’s eeriness is insinuated through its Kafkaesque motif: a fantastically gigantic bug of the hexapod family climbs up the girl’s thighs, which asymmetrically lean toward the left margin of the cover. Finally, the profile and bare shoulders of an unknown and sad-looking model (who appears to be slightly older than Lolita’s age) are delivered by means of high-contrast photography (15).

9. Moscow: Vodolei, 1991. [Design by V. I. Kharlamov. 317 pp., 300,000 copies; hardcover.]

10. Alma-Ata: Murattas, 1991. [328 pp., 15,000 copies; hardcover.]

11. Moscow: Khudozhestvennaia literatura, 1991. [416 pp., 100,000 copies; hardcover and paper.]

12. Moscow: Izvestiia (series: Biblioteka zhurnala Inostrannaia literatura), 1989. [368 pp., 100,000 copies, paper.]

13. Moscow: Prometei, 1990 [1991]. [Design by Aleksandr Kolomatskii. 284 pp., 300,000 copies printed in 1990; second printing of 70,000 in 1991, paper.]

14. Back cover of 13.

15. Minsk, Belorussya: Moka, 1991. [320 pp., 150,000 copies; hardcover.]

As soon as Nabokov’s scandalous fame gained international dimensions in the mid-twentieth century, a dense collection of intertexts and paratexts began to surround Lolita. Modern readers approach Nabokov’s iconic work with a sense of who and what Lolita is. This Lolita phenomenon functions in the same way as that of the legendary British spy James Bond, a figure who exists across films, books, merchandise, and ads. The James Bond case is an example of a particularly successful para- and intertextual network: The manifestations of Agent 007 work as “textual meteorites, highly condensed and materialised chunks of meaning.”24 Following Tony Bennett and Janet Woollacott’s premise, Jonathan Gray asserts that these “meteorites” influence any interaction we might have with another Bond text via the preexisting network, so that “we will always arrive at any new Bond text with a sense of what to expect, and with the interpretation process already well under way.”25 In a similar way, the Lolita effect spreads far beyond the narrative.26 Even the Nabokovs humorously accepted this “paratextuality” of Vladimir’s creation; on one occasion in 1966, during a photo shoot, a sunbathing Véra sported a pair of plastic heart-shaped sunglasses, almost identical to the pair Sue Lyon wears in the promotional poster for Stanley Kubrick’s film version of Lolita.

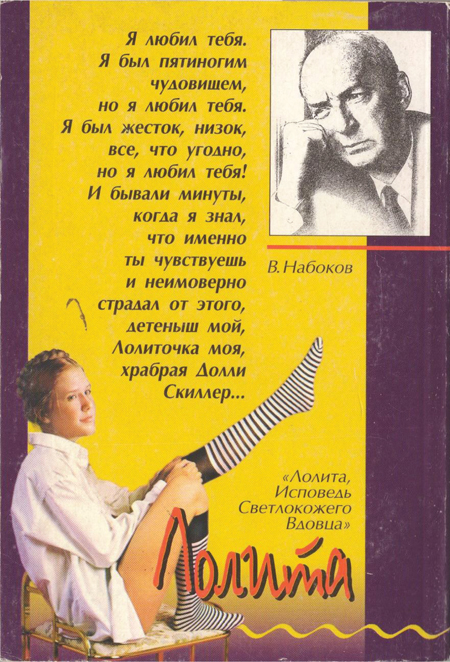

Unhappy with the Swedish edition of Lolita, Nabokov once commented to a prospective U.K. publisher that the cover “has a horrible young whore instead of my nymphet.”27 Several Russian editions have outdone even this assessment, although one could argue that the post-Soviet “young whore” looks “pretty” rather than “horrible” on the back cover of a 1998 edition of Lolita printed in Moscow (16), a city in which more than a thousand children were involved in prostitution in 1993. According to data released by the Russian police, children accounted for 25 percent of all prostitutes taken into custody in 2000. This proportion increased to around 27 percent in 2001, and new recruits are always in high demand.28 In the decade that followed, Russia’s national government demonstrated limited efforts to raise awareness and prevent child sex trafficking.29 It is hard to imagine an image like the 1998 one appearing on the cover of anything in a catalog of a reputable publishing house in the West.

16. Moscow: TF-Progress, 1998. [458 pp.; print run unknown; paper; back cover]

Since Lolita’s paratexts are in large part based on the book’s two Western screen adaptations, it may be argued that such sexual imagery radiates a special allure and hints at certain connections between the Russian Lolita covers and mainstream Hollywood production. To further explore this connection, first the nature of the relationship between a book cover and the materials used to market films (e.g., posters, ads, and cards) needs to be established. Cover images often perform the same role for books as trailers do for movies.30 On the one hand, as Andrew Wernick explains, “a promotional message is a complex of significations which at once represents (moves in place of), advocates (moves on behalf of), and anticipates (moves ahead of) the circulating entities to which it refers.”31 On the other hand, according to Gray, a significant part of that representation, advocacy, and anticipation is “genred by nature.”32 Lolita is not an exception and, therefore, it has been—and most likely will continue to be—exploited by publishers and book-cover designers who overemphasize the sexuality, only one of many themes found in Nabokov’s novel, with crudely enticing imagery or elaborately provocative hints. The latter include close-ups of sensuous lips, the depiction of underage girls in miniskirts, and wet, colorful lollipops. In contrast to Russia, the portrayal of a naturalistically drawn or photographed naked girl under the age of 18 is taboo as a book cover in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia; however, the aforementioned synecdoche of underage sexuality is the norm on many Western covers of Lolita, including those of major publishers such as Random House/Vintage International and Penguin. When designers challenge cultural norms, the results are poor: a number of popular Penguin classics, including Nabokov’s Lolita, were pulled from the shelves of Australia Post retail outlets as recently as 2009.33

The influence of the Hollywood productions of Lolita on the design of Nabokov’s novel in Russia has been lopsided. Except for a few cineasts, the post-Soviet reading public was virtually unaware of Kubrick’s 1962 film. Both the novel and its Western screen adaptation were banned in the country until the end of the 1980s. Therefore, Kubrick’s imagery lacked any cultural significance and could not serve as a frame of reference when marketing Nabokov’s work to audiences of the 1990s. But publishers have successfully made use of Lyne’s 1997 film. Though it was controversial in the U.S., the movie was heavily promoted in Russia and enjoyed wide distribution and many press mentions.34 As a result, most of the Lolita paperback editions published shortly after Lyne’s screen adaptation used the recognizable features of the actors.

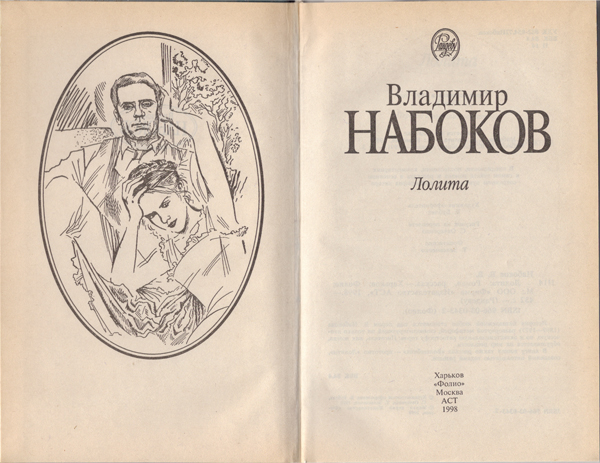

There are at least seven editions in Russia that incorporate Jeremy Irons and Dominique Swain into their cover designs. These covers commonly project innocence and peaceful love between the protagonists; the pain, rift, and dramatic tension remain hidden deep in the text, behind a deceptively romanticized façade (17–22; 24 and 25).

17. Kharkov: Folio; Moscow: AST (Rendezvous series), 1998. [Computer rendering and cover design by A. Kozhanov; 430 pp., 20,000 copies; hardcover.]

18. Flyleaf of 17.

19. Moscow: Tsentrpoligraf, 2002. [478 pp., 7,000 copies; hardcover.]

20. Moscow: AST, 1999. [478 pp., 10,000 copies; paper.]

21. Moscow: Eksmo-Press, 1999. [Design by E. Shamrai; 462 pp., 10,100 copies; paper.]

The back cover of one (22) is a comic example of crude image manipulation by a designer who could not find a suitable still from Lyne’s movie. An image of Swain’s head is attached to the body of an adolescent model (there is no such outfit worn by the actress in the movie, and a closer look at the neck exposes a rather unsophisticated splice of the two images).

22. Back cover of 21.

The popularity of Swain’s face among publishers, readers, and viewers can also be explained in psychological terms. There is ample research suggesting that people ascribe positive characteristics—intelligence, competence, leadership skills, etc.—to nice-looking people.35 Despite the consensus that judging a book by its cover is a risky strategy, readers still rely on signs like smiles, or the signaling properties of characteristics such as the gender, age, race, and ethnicity of those depicted on covers. Attractiveness indicates to us trustworthiness, both in real life and in our judgments of products, books in particular—especially those whose covers incorporate human features.

In the book, Dolores Quine makes her New York debut in Never Talk to Strangers, and Humbert later repeats the same fatherly advice to Lolita,36 but scientists prove that we turn a deaf ear to our parents’ warnings: “Subjects not only trust strangers, but also they choose to trust based on a stranger’s appearance.”37 Average features are found to be attractive. With respect to facial attractiveness, according to Rick Wilson and Catherine Eckel, this does not mean a commonplace visage, but rather one that carries the average features for the population. Numerous studies have shown that “blended” faces (those that are compiled from many different images) are more attractive than actual individual faces.38 Attractiveness remains an important marker, but it is largely a function of clear skin, clear eyes, shiny hair, and symmetry; as a fabricated reincarnation of Nabokov’s Lolita, a rather plain teenage Swain conforms to all these cultural and social expectations.

In partial defense of the cover designs based on Lyne’s film, it should be admitted that to a certain extent they do achieve Nabokov’s desire for “pure colors, melting clouds, accurately drawn details, a sunburst above a receding road with the light reflected in furrows and ruts, after rain” on the cover of Lolita39—with the notable exception, of course, that they feature the girl and her predator, both pensively looking in the same direction somewhere beyond the horizon.

Comparing three different editions of the novel, we find that the size of the fonts used for the author’s name and the novel’s title varies within a brief time span, indicating the evolving cultural significance that publishers assign to either of these two essential cover elements. In 1999, Nabokov, rendered in golden lettering, is still much larger than the title (23); soon, however, it is Lolita that draws the eye’s attention (24). Finally, everything comes to a relative balance on the Eksmo edition five years later (25). Although the fonts achieve a degree of proportionality, the screaming colors now explode any sensible typographic palette. Of course, for a Byzantium-oriented Russian aesthetics, it is hard to compromise on anything that has to do with decorative gold, and, fittingly, with its radiant gold circle inscribed within a square, the cover is reminiscent more of a glazed Orthodox icon than a screenshot from a Hollywood film.

23. Kharkov: Folio; Moscow: AST, 1999. [430 pp., 6,000 copies; hardcover.]

24. Mashen’ka. Zashchita Luzhina. Kamera obskura. Priglashenie na kazn’: Romany. Moscow: Eksmo-Press, 1999. [Designed by A. Yakovlev (Series Russian Classics); 800 pp., 10,000 copies; hardcover.]

25. Moscow: Eksmo-Press, 2006. [544 pp.; 5,100 copies; hardcover.]

As Russian spectators have increasingly absorbed international art-house cinema, particularly Hollywood’s black-and-white legacy, their cultural thesaurus and range of potential visual associations have expanded accordingly. Once this happened, it became possible to count on allusions to Kubrick’s film appearing among the stock of acceptable marketing strategies for Lolita in print. A 2010 edition presents Nabokov’s film script for Lolita translated into Russian for the first time (26). The cover image employs a still from the 1962 movie, but since the screenplay, as is well known, was heavily rewritten by Kubrick,40 the validity of the image of Sue Lyon and James Mason is suspect. The designer also could not resist adding color to the original shot (probably bowing to the trend of colorizing old black-and-white films, a practice that was fashionable in Vladimir Putin’s Russia of the 2000s).

26. Vladimir Nabokov. Lolita: A Screenplay. Moscow: Azbooka-klassika, 2010. [256 pp.; 10,000 copies; hardcover.]

The cover that attempts to capitalize on the proven commercial success of a movie thus presents a curious case of duplicating the same mechanism into an adjacent medium, or essentially bringing the film back to the literary sphere from which it was borrowed for screen adaptation. This effect has significant consequences for readers, especially for new ones who buy the novel in this “fresh old” packaging; the image dictates the novel’s reception and can shape the mental image of the characters—in this case, of Lolita.

After the initial wave of massive distribution of Nabokov’s “morally dubious” book had subsided, Russian publishers focused their attention on a few specific target groups. The segment of readership most suited for Nabokov’s prose, they decided, was the “intelligentsia,” who maintain high standards of cultural self-identification and have demanding reading interests. To be adapted to the needs of this intellectual market, Lolita required some repackaging—or rebranding—in the second half of the 1990s.

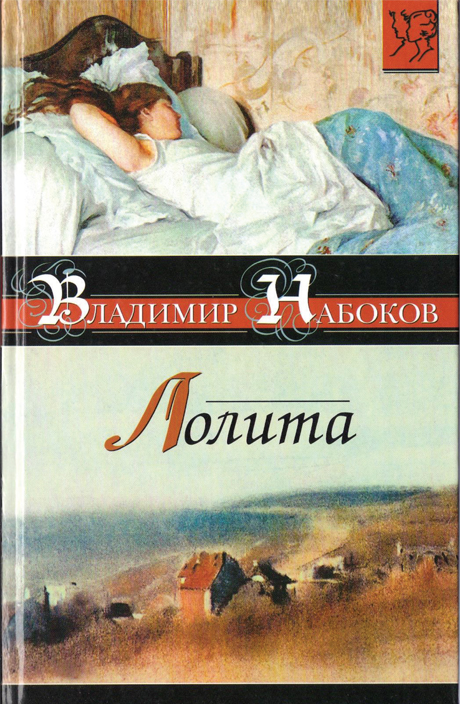

A fragment of Botticelli’s painting The Birth of Venus strikes one as a poor choice for the cover of a 1998 edition of Lolita (27). It depicts the naked Venus emerging from the sea as a fully grown goddess. Botticelli’s tall and slightly plump model is visually quite remote from the mental image of Nabokov’s nymphet that the average reader forms while reading the novel. Botticelli’s Venus appears in the text itself, although the fleeting comparison of petite Lo to the Renaissance beauty offers no direct clue for the layperson.41 However, the cover surely places Nabokov’s novel on the level of a great work of art, to suit its intended audience’s aspirations.

27. Moscow: Tekst, 1998. [448 pp.; 7,000 copies; paper; with credit to Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus for the cover art.]

For a visual representation of Lolita, the Eksmo-Classics edition features Gustav Klimt’s 1912 Portrait of Mäda Primavesi (28).42 Awkwardly positioned on the front cover beneath the title, the girl’s figure is not reproduced in full, and the lower part of her legs is cut off by the bottom edge (the deep-purple background above the girl’s head appears to be artificially attached, as it is not part of the original). The publisher’s logo is thoughtlessly placed over Mäda’s dress, between her thighs.

28. Moscow: Eksmo-Press; Eksmo-Market, 2000. [Design by A. Saukov, with credit to Klimt; 384 pp.; 7,000 copies; paper. Omits fictional foreword.]

When Klimt painted her portrait, the real Mäda (1903–2000), daughter of the banker and industrialist Otto Primavesi, was the age of a young nymphet, according to Nabokov’s own definition. Contemporary interpreters perceive this nine- or ten-year-old girl as being “on the verge of womanhood”:

The arm posed determinedly against the hip, the dead-on expression of neither offering a smile nor soliciting one. These are poses that work on us in the way advertising works on us —they make a nominal elicitation of the subject’s personal strength, but with their stereotyped poses, their glitzy, meaningless decorative backgrounds . . . they seem to be more about the sexual fantasies of the viewer than the viewed (Klimt was an avid Freudist).43

What makes Mäda different from other feminine portrayals by Klimt and his peers is her advertisement-like solicitation of her viewers. This direct appeal transforms the process of scanning a young woman’s image into a complex psychological experience involving the gazer’s self-reflection. As a book cover for Lolita, the classical portrait nolens volens endorses Humbert’s provocative diary, inciting additional ethical considerations in the reader’s experience of Nabokov’s novel.

Designers of post-Soviet Lolita covers often felt obliged to use pictures of girls who, if they were not entirely lecherous, at least promised promiscuity, a quality that was hinted at through the peculiarity of a pose, the ambivalence of a facial expression, or the setting. A number of Russian editions have been inspired by (or simply reproduced) the 1876 painting In Bed, by Federico Zandomeneghi, an artist who often depicted women in their domestic routines. This one shows a sleeping girl in a brightly lit room, unwittingly exposing a red-haired armpit.

At least five editions use the sensuous painting (29–33). One provokes a seemingly undesired effect: Due to the direction of the head in the insert (a photograph of Nabokov in his late thirties), there emerges a strange voyeuristic impression of the author spying on the sleeping beauty below him (30).

29. Moscow: AST, 2000. [Series design by A. Kudriavtsev; 368 pp.; 10,000 copies; paper.]

30. Moscow: AST, 2003.

31. Moscow: AST, 2004. [Print run unknown; 427 pp.; hardcover. Omits fictional foreword.]

A picture of a girl in bed ostensibly embodies the nymphet concept. One of these covers, however, places Zandomeneghi’s image in a stylized picture frame with a red rose beside it (32). In contrast to the crude depictions of a “young whore” used a few years earlier, a flower and an old-fashioned frame attempt to signify that Lolita is part of a venerable cultural and literary tradition. (Two of the editions featuring Zandomeneghi’s painting were released as part of two different series, “Classical and Modern Prose” and “World Classics.”)

32. Moscow: AST; Ermak, 2004. [702 pp.; 4,000 copies; hardcover. This edition also includes Nabokov’s novels Glory and King, Queen, Knave; Lolita omits fictional foreword.]

The 2003 AST cover is an interesting case of the sublimation of two themes from classical paintings (33). The cover’s upper half depicts the already familiar image of Zandomeneghi’s sleeping girl; the lower half presents a view of a serene village.

33. Moscow: AST, 2003. [Print run unknown; 427 pp.; hardcover. Omits fictional foreword.]

The latter is an 1869 landscape by Edgar Degas titled Houses on the Cliff Edge at Villers-Sur-Mer. It is unclear why the designer decided to conflate In Bed and the countryside scene, apart from the fact that Zandomeneghi, whose style was similar to that of the Impressionists, was Degas’s close friend. The red-brick roofs of the French village might also be meant to evoke the description of the landscape in the finale of Lolita: “The road now stretched across open country. . . . One could make out the geometry of the streets between blocks of red and gray roofs, and green puffs of trees, and a serpentine stream.”44 While it is doubtful that such subtle literary allusiveness was intended, the possibility should not be dismissed altogether.

A period photograph was used for an Azbooka edition, depicting a naked woman warming herself by a wood stove (34). As Patrick Cramsie suggests, the image’s unposed, snapshot quality, in addition to its potential for a penetrating degree of detail, harkened back to traditional forms of book illustration: “Realistically painted illustrations had remained popular in America, as elsewhere, despite the compelling novelty of the photograph and the exotic glamour associated with Modernist forms of abstraction.”45 Hence, an American device took root in Russia. Although the woman wears no clothes except for high heels, nothing graphic is actually exposed. The image also provokes a tension in the contrast between the girl’s nakedness and the coldness of the darkly lit room.

34. St. Petersburg: Azbooka-klassika, 2002. [446 pp.; 7,000 copies; paper.]

The source of this cover (as usual with the pirated Russian editions of that period, unacknowledged) is James Abbe’s 1928 photograph Bessie Love. Bessie Love, born in 1898, a year before Nabokov, was an American movie actress who achieved prominence mainly in silent films and early talkies. She was nominated for an Oscar in 1930, and a star bearing her name rests on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. When Lolita was published, the actress was taking part in movies with suggestive titles: Young and Willing (1954), The Barefoot Contessa (1954), and Touch and Go (1955). Abbe (1883–1973) was an American photographer with an interest in Russia, although Nabokov would have definitely disapproved of Abbe’s Soviet voyage. (His book I Photograph Russia appeared in 1934, and included one of the first officially sanctioned Western photographs of the dictator Joseph Stalin.) According to a now legendary account, during costume changes “while Abbe set up the lighting for the next shot, Bessie Love would sit and warm herself at the iron stove in Abbe’s studio. And there, in a moment, Abbe saw an image that would become one of his most famous.”46 For the cover of the Russian Lolita, the picture is cropped on the sides but compensates this loss on the vertical axis: digital retouching extends the iron stove’s chimney and elevates the room’s dark ceiling.

Another Art Nouveau–inspired Russian Lolita cover that takes advantage of a preexisting work of art features a close-up of a young woman’s profile (35). This edition is published in the suggestively titled series “Light Breath” (taken from Ivan Bunin’s famous short story of the same title), with the subtitle “Russian Love Prose of the Twentieth Century.” “Russian-ness” notwithstanding, the image on this allegedly quintessential domestic prose is of clear Western origin: it is actually taken from a poster by Joseph Christian Leyendecker (36), who was born in Germany in 1874, and immigrated with his parents to America eight years later. He took art lessons at the Chicago Art Institute, and after developing a distinct personal style, created over 400 magazine covers between 1896 and 1950. The peak of Leyendecker’s career was in the 1920s, and he became a chief source of inspiration for—and a friend to—Norman Rockwell.

35. Moscow: Infoserv; Forum, 1997. [446 pp.; 5,000 copies; hardcover. Omits fictional foreword.]

36. Advertisement for Cluett, Peabody & Co., year unknown (illustrator: Joseph Leyendecker).

Nabokov did not particularly praise Rockwell’s artistic merits, and his opinion of Leyendecker, this decorator of middle-class coffee tables (the epitome of poshlost or banality, in Nabokov’s view), was probably no better. Further irony derives from the fact that Leyendecker was gay and “attempted to conceal his sexual orientation in his work, which was often characterized by heterosexual female adoration for handsome males depicted in overtly erotic poses.”47 The girl on the cover is actually a fragment from an advertisement promoting the image of a smartly dressed young man. Leyendecker’s style, as in advertisements for detachable shirt collars manufactured by Cluett Peabody & Company, “established the beau ideal for the sartorially savvy American male.”48 The decision of a post-Soviet publisher thus succeeds in unwittingly connecting “the most manifest homosexual artist of the early twentieth century”49 and the novel about the pedophile Humbert Humbert.

Ekphrasis is usually defined as “the verbal representation of visual representation.”50 In the case of illustrating Lolita, we are essentially dealing with a reversed process that constructs visual representation based on a verbal account. If one were to try to re-create Lolita’s face in full accordance with Nabokov’s artistic vision through Identi-Kit principles (composite sketch methods used by police), it would prove to be an onerous task. First of all, although she is the central character of the novel, Lolita is shown through the prism of Humbert Humbert’s perception. The narrator frequently stresses the importance of his mental image of his little nymphet over her appearance in flesh.51 Secondly, when Lolita does appear in certain descriptive passages, her physical features seem elusively disjointed; hence, the reader must resort to accumulating her characteristics as they are described throughout the narrative, which may shed some light on Lolita’s true portrait. Lolita’s bare legs and knees (or even “narrow white buttocks”52) are mentioned much more frequently than her facial features. Whenever the text refers to Lolita’s face, it often limits itself to highlighting her freckles or dimples instead of giving a crystalline portrait in the familiar manner of the classical nineteenth-century novel. Because Lolita is seen largely through Humbert’s romanticizing and aestheticizing perspective, covers that employ renowned artworks actually capture Humbert’s own perspective of Lolita (e.g., the Venus); the fact that in the novel we see Lolita only in pieces—rarely (if ever) as a whole—is conveyed brilliantly in the covers that employ synecdoche or fragments of a girl’s body.

All this is in contrast to Lolita’s abuser, whose own portrait was recently rendered using a contemporary take on Smith & Wesson’s 1960s-era Identi-Kit, a collection of mix-and-match cards showing various types of facial features and hairstyles. Humbert is described in much more detail than Lolita, which allowed the Brooklyn-based artist Brian Davis to simulate the character’s simulated face, part of a project called “The Composites.” To create these portraits, Davis uses software modeled after the methods investigators use to create an image of a suspect.53 We know that Lolita’s face is “snub-nosed” and looks “almost plain, in a rustic, German, Mägdlein-like way”; that her eyes are “gray” and curls range from “brown” to “sunny-brown.”54 But is there enough data for a reliable portrait?

This rhetorical question should be rephrased in a more productive way: Why do cover designers opt for certain types of facial features and not others in re-creating their hypothetical Lolitas? Obviously, their goal is to produce a visual message that would emphasize the cover girl’s attractiveness. According to contemporary psychologists who study human aesthetic preferences, only a brief glance at a face is necessary for judgments of attractiveness to occur:

When people rated the attractiveness of faces they had seen for less than a quarter of a second, their judgments showed strong agreement with those made by others whose viewing time was not constrained. The consensus on attractiveness holds true regardless of the sex or race or age of those being judged. People show agreement on which face is more attractive whether they are judging males or females, people from their own or a different racial background, infants, children, teenagers, young adults, or old adults. . . . People also make more distinctions regarding the attractiveness of female than male faces, and they give more extreme ratings to female faces.55

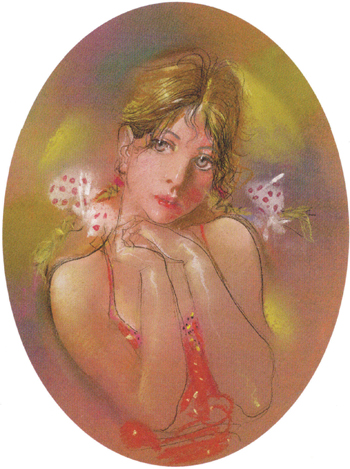

Readers’ brief glances at a cover in a bookstore, especially if they are not familiar with the author or the contents of the novel, are a decisive factor in browsing through a book and, ultimately, buying it; this explains the attempt to maximize the cover’s attractiveness.56 Zebrowitz emphasizes the importance of the perceived youthfulness of a female face in judging her attractiveness: youthfulness provides a possible explanation for the greater appeal of some faces over others, and if “younger looking people are more attractive, babyfaceness should enhance attractiveness.”57 Important when considering publishers’ depictions of Lolita is the argument that specific “babyish” features have been linked to attractiveness: “Among these are large eyes, large pupils, and a small nose. Eyes are particularly influential, typically showing moderate-to-large effects on attractiveness, although these effects are more reliable for judgments of female than male faces.”58 It has also been established that men find youthfulness of the opposite sex more attractive than women do. This study is also applicable to the Humbert-Lolita paradigm, since it suggests “a large and universal tendency for men to prefer younger mates than women do. Although this sex difference in human mate preferences is consistent with the evolutionary hypothesis that men will find youthfulness more attractive than women do, it does not implicate perceived fertility as the most important determinant of attractiveness.”59 If it were, Zebrowitz maintains, one would expect men to prefer women younger than twenty-five years of age, since peak fertility in women occurs in the mid-twenties. Even if men really do prefer younger women, this alone does not establish perceived fertility as the causal factor, nor does it prove that variations in physical attractiveness are crucial to the choice of partners.60 Bearing in mind these scientific findings, let us examine the cover of a Lolita published in 1998 (37).

37. Moscow: TF-Progress, 1998. [458 pp., print run unknown; paper.]

The structure, proportions, configurations, colors, angles of lighting, perspective, and many other components in the picture conform to an ideal image of the fictional heroine, who combines suggested puberty with implied innocence; this innocence is undermined, however, by the bold color of the girl’s lipstick and her décolleté dress. The placement of the girl’s face in such a way as to fill the entire space of the cover brings to mind a similar practice used in popular illustrated magazines, which make their revenues by reporting celebrities’ shocking and intimate news. Cramsie, the author of a book on the history of graphic design, writes that the editors of picture magazines understand the importance of an image in the wider sense of the word: “An important element in defining the image of the magazine to the potential buyer was the photograph that appeared on the cover.”61 Initially, picture magazines showed a variety of subjects, but soon publishers “realized the pulling-power of a recognizable or attractive face, or ideally one in which both characteristics were combined.”62 The preferred cover image evokes female beauty and youth, and these priorities have remained more or less constant. (As Richard Stolly, the first editor of People magazine, put it, “Young is better than old. Pretty is better than ugly. Rich is better than poor. TV is better than music. Music is better than movies. Movies are better than sports. Anything is better than politics. And nothing is better than the celebrity dead.”63) The feature that makes the face so very compelling is the eyes, and indeed Lolita’s viewpoint on this cover succeeds in establishing direct eye contact with the viewer (a potential customer). It is reminiscent of the Identi-Kit approach discussed earlier, not only due to the en face angle but also because the fake Lolita’s face is constructed of a compound of features comprising a set of cultural clichés. And if the buyer of the book with the brazen cover bothers reading the novel to the very end, he will be gratified to discover that the pretty cover girl is no longer alive—“nothing is better than the celebrity dead.”

The image of the girl sporting a short haircut is not an original photograph commissioned by the Russian publisher but comes from the website of a Japanese modeling agency.64 The original face was slightly retouched: the red color of the lips has been intensified, and her eyes have been color-corrected to deep blue from gray (which would have been true to Nabokov’s text), as if to conform to a stock beauty ideal. A modern designer has also erased traces of either acne or birthmarks from her upper chest area.

As seen from the sample illustrations, Lolita is most often represented as a blonde girl with light-colored eyes. This hardly establishes her as belonging to any ethnicity or cultural tradition, but there is a tendency among Russian publishers to use either girls with distinctively Slavic features or reproductions of works made by Russian artists. A Russian model (although belonging to a minority ethnic group called Komi) was used, for example, for a 2005 cover (38). This is a slightly truncated image taken from Portrait of Ria (Portrait of A. A. Kholopova), by the avant-garde artist Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (39). It might represent either Lolita or Mary—the heroines of Nabokov’s novels of the same names—since both books are collected in this edition.

38. Moscow: Eksmo-Press, 2005. [800 pp.; 4,000 copies; hardcover; also includes Mary and The Luzhin Defense.]

39. Portrait of Ria (Portrait of A. A. Kholopova), by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (1915).

The painting was completed in 1915, when the girl, Ariadna (nicknamed Ria), was between ten and eleven years old, which makes her, in Humbert’s terminology, the age of a nymphet. Curiously, this painting was done in Petrograd while Nabokov was still living in the city. To make his young subject sit quietly, Petrov-Vodkin offered a large box of chocolates and told her adventure stories in installments, ending each episode at the climactic moment in order to make Ria want to return and pose for him again.65 According to Ria, the sculptural face that appears in the background was not there at the outset. It was added later, possibly to emphasize her antique name or her slanting eyes and prominent cheekbones, considered typical Komi facial features. To underscore the girl’s sensuality, as many other Lolita covers have done, the designer of this edition intensified the redness of her cheeks and lips. The painter’s signature has been cropped out—it obviously was not needed in an era of unobserved copyright.

Based on his readerly experience, Sergei Dovlatov, a prominent writer of the third émigré wave and a favorite of The New Yorker, once claimed that “all of Nabokov’s Russian personages look alive, while his foreign ones are predictable and decorative. His only live foreigner is Lolita, but even she, judging by her personality, is a typically Russian miss.”66 As if concurring with this definition, another Russian publisher put a teenage schoolgirl with typical Slavic facial features and dressed up as a cheap harlot on its cover of Lolita (40).

40. Rostov-na-Donu: Feniks, 2000. [Design by Iu Kalinchenko. 448 pp. (Series: Classics of the 20th Century); 10,000 copies; hardcover.]

In addition to using faces of a certain type (dubious and subjective criteria), Russian-ness can be suggested via clothing. For instance, a Lolita in a stylized sailor’s jacket (42) echoes a portrait from Nabokov’s own prerevolutionary childhood (41). On the one hand, there is something innocent in her inquisitive gaze; on the other hand, the boyish girl holding a flower to her lips is meant to look seductive. (Nabokov, by the way, probably would not have welcomed this semblance to his own outfit because of the Freudian twist inherent in such transgender photographic conversions.)

42. St. Petersburg: Kristall, 2001. [Design by I. Mosin. 352 pp.; 10,000 copies; hardcover]

41. Vladimir Nabokov in St. Petersburg, 1906. Photograph courtesy of the Estate of Vladimir Nabokov, used by permission of the Wylie Agency LLC.

Among those Russian editions that attempt to recalibrate the image of Lolita as an American teenager by representing her as a young Russian lady is a 2001 edition of the novel, jointly published by St. Petersburg and Moscow presses (43 and 44). In a rare credit, the hired illustrator’s name is listed in the bibliographic record. The artist, A. Vassiliev, places a Slavic-looking face under the Russian title Lolita; the head, tilted to the left, continues the line formed by a large birch branch protruding at an angle from the upper left corner.

43. St. Petersburg: Izdatel’skii Dom “Neva”; Moscow: Olma-press, 2001. [Design by A. Vassiliev. 383 pp. (Series Grammatika liubvi); 5,000 copies; hardcover.]

44. Back cover of 43.

The birch serves as an unmistakable symbol of Mother Russia; the smiling girl with “sunny-brown curls” (in full agreement with Nabokov’s verbal portrait) fading into the background is also of a recognizably Slavonic pedigree. The concept of Russian-ness is reinforced by the back-cover image, which depicts a typical landscape of an unmowed lawn in front of a Chekhovian dacha. It features a middle-aged man offering a small gift box to a girl in a miniskirt who sits above him on a windowsill. Presumably, the couple represents Humbert and Lolita, and the photo was likely staged for the cover.

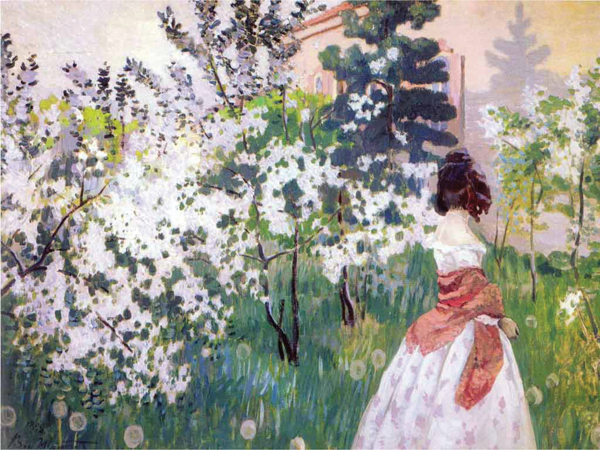

Another allegedly typical Russian floral motif surfaces on the cover of an edition issued in the “Ladies’ Album” (Zhenskii Albom) series (45). An impressionistic image of a lilac bush is positioned on the right half of the cover (the source is Victor Borisov-Musatov’s painting Spring, completed in 1901; 46).67 A vignette of a naked woman lying with her legs crossed, executed in the style of an ancient Greek vase, is on the left in the place of Borisov-Musatov’s chaste, old-fashioned young lady.

45. Moscow: Ripol Klassik, 2002. [Design by K. Salina and V. Borisov-Musatov. 448 pp. (Series Zhenskii al’bom / Ladies’ Album); 5,000 copies; hardcover. Omits fictional foreword.]

46. Spring, by Victor Borisov-Musatov (1898–1901).

The flyleafs in a Neva–Olma edition continue the Garden of Eden theme, suggesting the loss of childhood via an empty rocking chair and an abandoned doll in the grass (47). The second illustration from the same edition (48) shows a close-up of Humbert reclining over his sleeping Lolita. (His profile closely resembles that of Jeremy Irons, the actor from the 1997 film.)

47. St. Petersburg: Izdatel’skii Dom “Neva”; Moscow: Olma-Press, 2001. [Endpapers.]

48. Flyleaf illustration from 47.

The back cover bears a quote from Ovid about suffering from love,68 and the novel is printed in a series called “The Grammar of Love.” But I. Burova, the author of the introductory note, demonstrates her phenomenal ignorance about the book. After a brisk paragraph summarizing Nabokov’s biography she announces: “The most famous of Nabokov’s novels, Lolita was published in English in 1947, and then in the author’s translation into Russian in 1955.” Had Burova bothered to read Nabokov’s postscript (included in the edition), it would have at least spared her from the factual errors. Her wild interpretations would have also benefited from a little bit of restraint: “The novel is structured as the monologue of a hero, whose tumultuous and aggressive passion for a twelve-year-old Lolita pushed him to an abduction. But the girl is far from being irreproachable; in spite of her tender age, she is already marked by vice. It is she who seduces Humbert, and therefore it comes as no surprise that later she escapes to join another lover, mature and impetuously dissolute.”69 The inclusion of Nabokov’s afterword is a generous gesture, considering the fact that some early editions of the Russian Lolita did not even include the fictional John Ray, Jr., Ph.D., foreword. Inattentive and hasty publishers did not regard it as an integral part of Nabokov’s narrative and omitted it as unnecessary! Such misreadings, omissions, and factual errors suggest that they did not understand the product they were marketing.

Though Nabokov’s style often invites bombastic discourse that smacks of a flowery and pathetic style, the cover blurbs found on the Russian Lolita conform to the general trend of adding promotional value. The cover blurb is a relatively recent innovation in publishing. According to Gérard Genette, it came into widespread use during the 1960s, when enormous paperback print runs made the earlier review slip costly and impractical.70 At the same time, the cover praise highlights the book’s status as a commodity. As Alan Powers observes, “a book jacket or cover is a selling device, close to advertising in its form and purpose.”71 The cover blurb thus “represents a key element of the process of the desacralisation of the book, which caused a storm of controversy amongst French intellectuals in the early to mid-1960s in a debate which became known as the ‘querelle du poche.’ ”72 In a similar vein, cinema is also considered a perfect promotional vehicle for prose, as demonstrated by a blurb for Lolita that references Lyne’s film even before introducing the novel: “Adrian Lyne’s famous erotic masterpiece 9½ Weeks was watched by a record number of viewers despite the censorship bans. . . . Ancient Eros knows no morality laws. . . . Humbert’s soul has died in the days of his youth along with Annabel. But his feeling did not vanish.”73 A 1998 edition entices the reader with the following copy: “This is the book that many have dubbed the most scandalous novel of the twentieth century. . . . This is Lolita. The book that once stirred an incomparable commotion and still continues to do so. The book which people hate and admire, the book you can’t afford not to read.”74 And while the blurb is not an invention of the Russian publishing industry, one can certainly credit it for adjusting Nabokov’s émigré prose, with its dazzling style and vocabulary, to the norms of Soviet parlance, disfigured during the years of Bolshevik rule; after all, the same edition bears a warning: “The book, in general, follows the punctuation and orthography of the author.”

Among the few covers that feature original graphics is a 1998 edition made with illustrations by the artists V. Bublik and S. Ovcharenko. Here, Lolita is stylized as a doll in a cagelike crinoline dress (49 and 50).

49. Kharkov: Folio; Moscow: AST (The Rendezvous series), 1998. [Design by B. Bublik, cover art by S. Ovcharenko, frontispiece by T. Zelenchenko. 432 pp.; 15,000 copies; hardcover. Omits fictional foreword. Also includes Volshebnik/The Enchanter.]

50. Back cover of 49.

This cover makes a significant statement regarding the nature of Lolita’s entrapment: she is ensnared by a kind of bodily cage (rather than a cage distinct from her body), as though Humbert’s desires have turned Lolita herself into her own prison; indeed, if she could be someone else, she wouldn’t attract Humbert’s gaze and be trapped by it. These are also much less realistic depictions of Lolita, therefore demanding interpretation via metaphor to understand their meaning.75

One of the only known Russian covers of Lolita to feature a butterfly is an austere Symposium edition (52). Like its forerunner (51), it takes into consideration Nabokov’s own passion for lepidoptery,76 but can also be interpreted as a metaphor of Lolita captured by Humbert the hunter.77

51. Vladimir Nabokov. Lolita. Moscow: Izvestiia, 1990. [Series Biblioteka zhurnala Inostrannaia Literatura / The Library of the Foreign Literature magazine. 368 pp.; 300,000 copies; paper.]

52. Vladimir Nabokov. Lolita. St. Petersburg: Symposium, 2001. [Cover design by Andrei Rybakov. 496 pp.; 10,000 copies; hardcover.]

Every book has a cover, but behind every successful cover there is an even more successful brand. Even e-books are marketed to emphasize their generic proximity to their paper prototypes. Literary works whose brand value gains a cult status frequently become exploited as objets d’art. In Russia, Lolita has undergone a transformation in its reception by readers: from a forbidden book to an acceptable and then desirable item to have in one’s personal library. If a copy of Lolita had been found among a Russian’s belongings in the 1970s and 1980s, it could have meant a prison term for its owner. Owning the book during the years of the Brezhnevian stagnation signified political audacity and liberal aspirations; starting in the early 1990s, having the formerly forbidden novel was regarded as a sign of refined taste and being up-to-date with popular fiction. But today, what makes the real difference in status is the actual quality of the material book one possesses, especially considering the vast selection of paperback editions available.

An emerging trend in publishing Lolita for “New Russians”—or novye russkie, wealthy oligarchs and passionate collectors—is the printing of limited editions of the novel. In 2006 the boutique Moscow publishing house Deitsch issued a “VIP edition” (as its promotional booklet calls it) of the novel as part of its series “Temptation” (Iskushenie; 53). Adorned with an innocuous floral design and baby-faced dragons, this edition is meant to attract the book connoisseur with the quality of its binding and print. Promoted as a “sumptuously illustrated edition in a compound binding, hand-made of leather and silk with 24-carat-gold lettering, and encrusted etching,” it is truly impressive, including the cost: $3,000.78 Compare this with the current asking price of $1,150 for the first American edition of Lolita, a hardcover with near-fine dust jacket.

53. Vladimir Nabokov. Lolita. Moscow: Izdatel’skii dom Deitsch, 2006. [Designed by M. Oreshina, A. Bondarchenko, D. Chernogaev; 423 pp.; 99 copies; leather binding.]

This special edition of Lolita includes over one hundred black-and-white pictures printed on an Italian chalk overlay paper; the binding is made of goat leather. All books by the Deitsch publishing house are printed in either Austria or Italy. The editions are limited (just 99 copies of each), and each book is individually numbered. Those who wonder if a Russian-language Lolita designed for rich Nabokophiles would find enough interested buyers will be interested to learn that this mammoth edition (weighing 3.7 pounds) is no longer available; it is now a bibliographic rarity.

Deitsch’s was not the only deluxe edition of Lolita published in Putin’s Russia. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, an emerging bourgeoisie has learned to appreciate the aesthetic beauty of a bookshelf, complete with volumes with solid bindings, behind a corporate office desk or next to a fireplace at home. Ideally, these shelves contain special editions, such as the Deitsch release discussed, or an even rarer publication, like the 2008 edition released by the St. Petersburg publishing house Vita Nova (54 and 55). This edition is hard to obtain and has no price tag, although it is advertised through the major Russian Internet vendor Ozon.ru, an equivalent of Amazon.com; those interested in this rare and expensive book are encouraged to contact the publisher directly.

54. St. Petersburg: Vita Nova, 2008. [Designer and illustrator: Klim Li. 576 pp.; leather binding.]

55. Front and back covers and spine of 54.

Four artists labored on this hand-made edition of Lolita: Olga Lavrukhina was responsible for the general concept; S. Lotov and E. Nikolaeva crafted the morocco binding, which was imported from Germany, as well as the moiré silk endpapers; and Yuri Panchenko was the edition’s metalsmith, responsible for the silver inlay. The book also contains an original etching by Klim Li.79 This collective enterprise is an interesting example of cooperation among publisher, editor, production manager, and craftsmen. In order to realistically exercise his imagination, the contemporary book designer no longer needs a working knowledge of hundreds of typefaces, but still must have “a familiarity, or even better, a practical skill, with the techniques of book printing, photography, and art; and the ability to render on paper an anticipation of the final appearance of the book. His layouts must be attractive enough to convince the publisher that the design will enhance the text, that it will be appealing in the bookstore as well as satisfying in the reader’s hand.”80

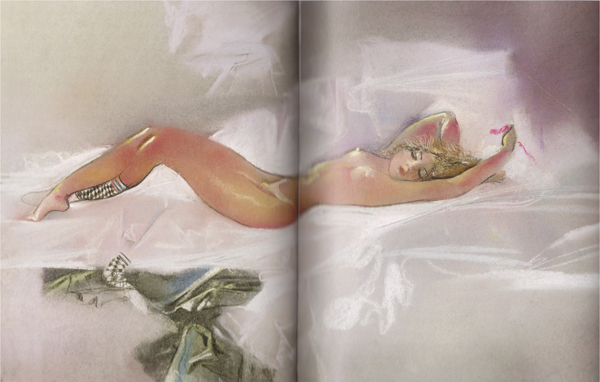

The success of the Vita Nova model is evident, especially considering that this was not its first experience publishing Lolita. The same house issued Nabokov’s novel in 2004, in a print run of 1,500. Li contributed graphic sheets, watercolors, and pastels to this relatively less expensive edition (56–65). In addition to Li’s sixty reproductions (forty of which are color plates), it included extensive academic commentary by Alexander Dolinin, a professor of Slavic languages at the University of Madison-Wisconsin. This edition is bound in natural tumbled goatskin and sells for approximately $60.

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

56–65. St. Petersburg: Vita Nova, 2004. [Designer and illustrator: Klim Li. 576 pp.; 1,500 copies; hardcover.]

Li’s pastels are an interesting take on the problem of illustrating Nabokov’s work. On the one hand, the pictures seem overly staged, and the artist’s interpretation of Lolita hardly captures the essence of Nabokov’s nymphet. On the other hand, it has been stated that “any illustration either interacts with the text or interferes with it. The impact of an illustrated story differs from that of the same story without illustration. Different illustrations for one and the same text result in changed moods and appeals.”81 Whether it is decorative, descriptive (in the sense that it repeats what the text tells), or narrative (in the sense that it interprets, as Joseph and Chava Schwarcz maintain), an illustration reaches beyond the text and may even contradict it.82 In this case, Li’s pictures work on a descriptive level rather than a narrative one, since they do not offer any specific interpretation, but they do affect the reader’s perception by imposing a reflective, romanticized, and languishing mood on Nabokov’s novel.

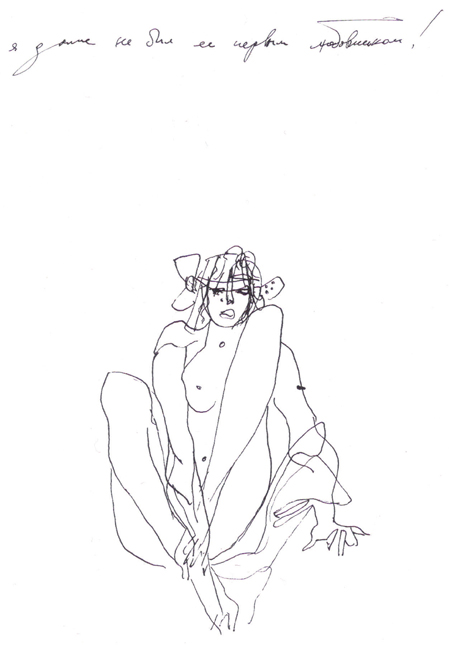

The graphic plates in the Vita Nova edition are more successful and exemplify how illustrations of various types mix in the same book to produce a versatile effect. Li’s expressive lines, executed in a quick, seemingly unfinished manner, render visible the implied eroticism of the novel. His plastic vignettes, mixed with overlaid handwritten notes (presumably, these are samples of Humbert’s diary or Nabokov’s writing), complement the overarching concept of a “manuscript” (the word manuscript is the title of the series in which Vita Nova published Lolita in 2004).

Li’s illustrations can be traced back to the work of Barbara Nessim, a renowned artist, illustrator, and educator whose graphic nude was used in a 1997 Russian edition of Lolita (66). Nessim began her career as a freelance fashion illustrator and over the past several decades has became an influential figure in the art world.

66. Moscow: Infoserv; Forum, 1997. [Illustrator: Barbara Nessim; 446 pp.; 5,000 copies; hardcover. Omits fictional foreword. Title and facing pages.]

Her image, reprinted in the Russian version of Lolita, has nothing to do with Nabokov. It is taken from her “Sketchbook” series, self-published pen-and-ink drawings made in the 1970s (when she also created the sexually provocative “WomanGirl” series, a collection of works rendered mainly in watercolor, pen, and ink). Lolita is not the type of book that should contain only decorative, descriptive, or narrative illustrations. It is likely that future illustrations that accompany Nabokov’s novel will evolve into a complex and exciting art form, combining both realistic and abstract approaches while striving to “overcome cultural boundaries” and “to offer entertainment and enlightenment in a metanational framework.”83

Text and jacket images are interrelated, especially when considering the marketing strategies and social positioning of a book through its intellectual legacy. Nabokov’s Lolita is doomed to struggle with both. It is not so much caught between lowbrow and highbrow literary genres, but rather it is at the mercy of mutating marketing strategies and the changing preferences of readers. As a result of marketing aimed at increasing profit margins and dealing with a totally unexplored niche in the industry, editions of Lolita often represented the exact opposite of what Nabokov himself desired (a noncommercialized version of his literary nymphet). By focusing on the visual aspects of Russian-language editions of Nabokov’s Lolita and surveying their controversial place in the contemporary Russian book market, it has been demonstrated here that Russian publishing institutions often misunderstand the very product they market, especially in the case of the Russian Lolita. But this is not a mere ethical or aesthetic fallacy. Unlike their Western publishing counterparts, who have consciously tried to engage audiences through provocative cover statements, Russian entrepreneurs are in the process of reclaiming a formerly prohibited writer, just as they’re on a path of self-discovery in areas of new economic policies, free trade, and unrepressed book design.

1 Vladimir Nabokov, Selected Letters, 256.

2 On Nabokov and Playboy, see: Leving, “Nabokov, Playboy, and the America of the 1960s,” (forthcoming). Apparently, Marilyn Monroe thought very highly of Nabokov (see: Boyd, 408).

3 Sinnema, Dynamics of the Pictured Page, 30.

4 On Nabokov and cover art in the West, see: Maliszewski, “Paperback Nabokov”; Duncan White, “Dyeing Lolita.” About reflections on Nabokov in popular art, including Russian culture and modern literature, see: Leving, Imperiia N, 125–180.

5 See, for example, the extensive discussion in a collection of articles appropriately titled Judging a Book by Its Cover (Matthews and Moody).

6 Groves, “Judging Literary Books by Their Covers”; McAleer, Popular Reading and Publishing in Britain 1914–1950, 85.

7 Schmoller, “The Paperback Revolution,” 288; Tanselle, “Book Jackets, Blurbs and Bibliographers,” 1971; Matthews and Moody, Judging a Book by Its Cover, xii.

8 Tanselle, “Book Jackets, Blurbs and Bibliographers,” 102–3.

9 Matthews and Moody, Judging a Book by Its Cover, xii.

10 Aynsley, “Fifty Years of Penguin Design,” 120.

11 Matthews and Moody, Judging a Book by Its Cover, xiii.

12 Maliszewski, “Paperback Nabokov,” 2001.

13 Nabokov, Selected Letters, 256.

14 Nabokov to Walter J. Minton, March 1958 (Nabokov, Selected Letters, 250).

15 Ibid., 256.

16 Wilson, The Design of Books, 106.

17 Ibid.

18 Cf.: “In spite of indications both in the United States and in Europe of a considerable increase in well made, well laid-out paperbacks, the bulk of the books are still for the roman policier and the blood and sex markets. Once again we revert to packaging and find some very lively, good looking covers, standing out like flowers amongst all the corn. The use of display letters with no illustrations is still a rarity” (Lewis, The Twentieth Century Book, Its Illustration and Design, 253).

19 See, for example, one such documented instance filmed with the interviewer Robert Hughes for a show called USA Arts: USA the Novel (NET National Educational Television, New York. Broadcast February 3, 1965).

20 See his afterword to the Russian edition.

21 Véra Nabokov to Fred Jordan; November 13, 1966 (the business correspondence files at the Vladimir Nabokov archive, Berg Collection, NYPL).

22 Martynov, Vladimir Nabokov, 89–90.

23 Nabokov, Lolita, (Moscow: ANS-Print, 1991), 256 pp.

24 Bennett and Woollacott, Bond and Beyond, 44.

25 Gray, Show Sold Separately, 34.

26 See Durham, The Lolita Effect.

27 Nabokov, Selected Letters, 274.

28 These and other alarming facts are quoted from “Child Prostitution Becomes Global Problem, With Russia No Exception,” Pravda.ru. October 11, 2006 <http://english.pravda.ru/society/stories/11-10-2006/84991-child_prostitution-0/> (accessed June 12, 2012).

29 This is according to a report by the United States Department of State: “2011 Trafficking in Persons Report—Russia.” June 27, 2011 <http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4e12ee50c.html> (accessed June 12, 2012).

30 One cannot underestimate the importance of a trailer to the film industry. Gray asserts that most Hollywood films make over a third of their box-office earnings in their opening week, and that “high opening-week box office figures have a compounding effect, giving rise to further hype to bring audiences for the rest of the film’s run” (Gray, Show Sold Separately, 49).

31 Wernick, Promotional Culture, 12.

32 Gray, Show Sold Separately, 52.

33 The History of Sexuality, The Delta of Venus, and Lolita were delivered to some of the 4,500 Australia Post stores nationwide, but all were sent back. Most did not make it as far as the shelves. Penguin Australia’s sales director, Peter Blake, said: “I guess there have been complaints from customers and they have reacted by removing them from sale. Retailers can do what they like” (Hawkins and Harvey, “Penguin Classics Prove Too Risque for Australia Post”).

34 About Nabokov’s screen adaptations and their reception, see Vickers, Chasing Lolita, 55–92; Wyllie, Nabokov at the Movies, 2003.

35 Wilson and Eckel, “Judging a Book by Its Cover,” 191.

36 Nabokov, Lolita, 32; 138; 309.

37 Wilson and Eckel, “Judging a Book by Its Cover,” 199.

38 Ibid., 200.

39 Nabokov, Selected Letters, 437.

40 Trubikhina, “Struggle for the Narrative.”

41 When Humbert meets the now-married Lolita after his long searches, he comments: “I definitely realized, so hopelessly late in the day, how much she looked—had always looked—like Botticelli’s russet Venus—the same soft nose, the same blurred beauty” (Nabokov, Lolita, 270).

42 Oil on canvas, 1912 (oil on canvas, 150 × 110 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

43 Tórrez, “A Painter’s Progress.”

44 Nabokov, Lolita, 306–307.

45 Cramsie, The Story of Graphic Design, 224.

46 See Winship, “Bessie Love, James Abbe.”

47 Cutler and Cutler, J. C. Leyendecker, 55.

48 The biographical essay devoted to J. C. Leyendecker (1874–1951) is available at the Haggin Museum <http://www.hagginmuseum.org/leyendecker/biography.shtml> (accessed March 15, 2012).

49 Cutler and Cutler, J. C. Leyendecker, 55.

50 Heffernan, Museum of Words, 3.

51 Cf.: “I see Annabel in such general terms . . . with shut eyes, on the dark innerside of your eyelids, the objective, absolutely optical replica of a beloved face, a little ghost in natural colors (and this is how I see Lolita)” (Nabokov, Lolita, 11); “She was thinner and taller, and for a second it seemed to me her face was less pretty than the mental imprint I had cherished for more than a month” (111); emphasis added.

52 Nabokov, Lolita, 137.

53 See: Edward Moyer, “Police-Sketch Software Puts Faces on Fiction Characters,” CNET TV news report. February 15, 2012 <http://news.cnet.com/8301-17938_105-57377131-1/police-sketch-software-puts-faces-on-fiction-characters/>; also on the personal blog of the artist Brian Joseph Davis: <http://thecomposites.tumblr.com/> (accessed May 18, 2012).

54 Nabokov, Lolita, 48; 120; 162; 180.

55 Zebrowitz, Reading Faces, 118.

56 The owner of a book store, Schmitz likens the process of choosing new titles to speed dating, where singles move from one prospective date to another, trying to analyze one one’s potential in a few short minutes: “When I meet with the publishers’ sales representatives, they have a limited amount of time to present all of their company’s new offerings. Each title is reduced to a few sound bites: title, author, print run, marketing plans, brief plot summary, intended audience. I must size up the contenders for space on my shelves and decide on the spot whether to purchase or skip a title. Just like speed-dating participants, I have to make my decision based on first impressions and gut instincts. Am I picking a winner, or is this book going to be as disappointing as a bad date?” (Schmitz, “Judging a Book by Its Cover,” 616).

57 Zebrowitz, Reading Faces, 127.

58 Ibid.

59 Ibid., 129.

60 Ibid.

61 Cramsie, The Story of Graphic Design, 225.

62 Ibid., 226.

63 Quoted in Cramsie, The Story of Graphic Design, 226; the source is Colacello.

64 Source: <http://www.faxingw.cn/liuxingfaxing/333_2_detail.html>

65 An excerpt from the memoirs of Ria [Ariadna Shmidt (1905–198?)] describing the modeling for Petrov-Vodkin is reproduced in Malysheva, “Portret Rii.”