Peter Mendelsund

“Lolita discussed by the papers from every possible point of view except one: that of its beauty and pathos.” —Véra Nabokov

“Be an active trader between languages.

Carry precious metals from one to the other.”— Vladimir Nabokov

I was recently asked to judge a book-cover competition. I’ve judged several of these things over the years, but this contest was rather unique; it comprised unpublished covers commissioned expressly for the jury to ponder, rather than ones already sold commercially. More unusually, the style of the covers was set in advance.

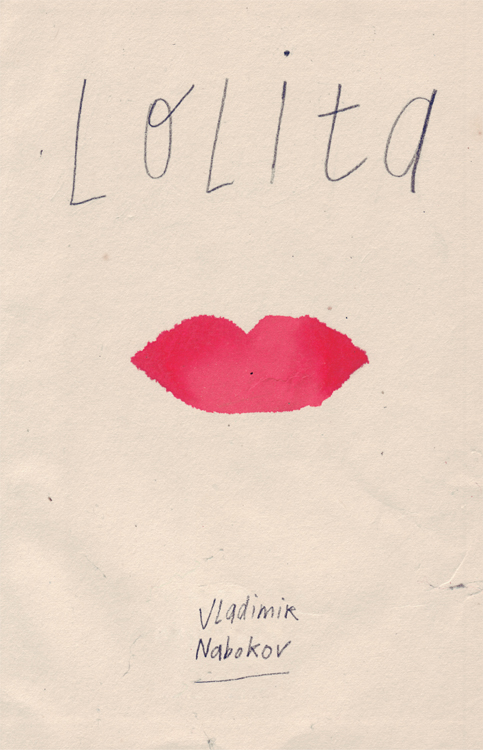

I found myself repeatedly coming back to one particular contestant’s book cover, dwelling obsessively on it. The cover in question (1) was submitted by Emmanuel Polanco, and it’s a proposed jacket for Nabokov’s Lolita.1

1. Proposed cover for Lolita (Emmanuel Polanco).

Is it the crude handwriting that makes it so effective? Doesn’t the entire composition, in its offhandedness, carry the faintest suggestion of the childish about it? It is neither lusting nor leering, nor overly proud of its own wit.2 It seems to eschew the urbane gaze of Nabokov’s old-world narrator in favor of a naive and guileless one. The painted lips hint at an underdeveloped, mythologized understanding of romance; it is the cover, I could imagine, that a young Dolores Haze might have drawn.3

I’m sure the effect is unintentional. And yet, the naïveté suggested by this cover reminds me that the unequal object of Humbert Humbert’s attentions is a child. And this line of thinking, in turn, reminds me that Lolita is, and should continue to be treated as (despite its verbal gymnastics, lasciviousness, and intermittent humor), a shocking and sad book (Dolores, or sorrows). It is not a sexy book; not an erotic book.

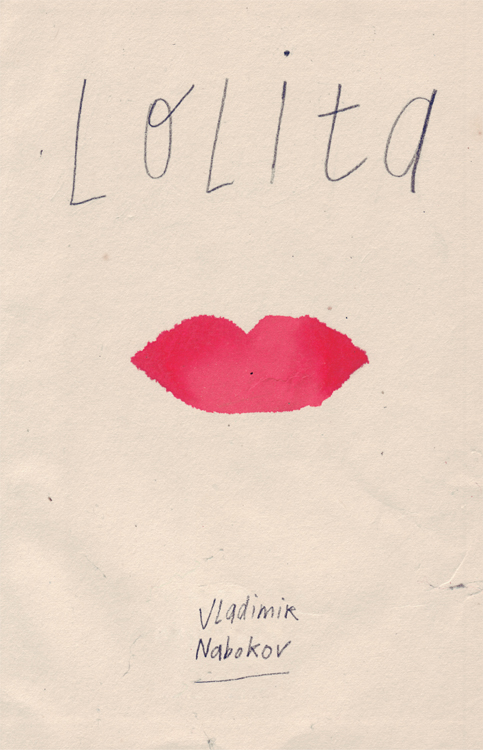

2. Lolita, Dutch-language edition (1970s), Omega Boek.

§

It is easy to forget, especially easy given the soft-core Lolita renderings (book jackets, film adaptations) one has seen through the years. Nabokov’s is a tale of perversion—unequal partnership, corrupted youth, and nonconsent Lolita is, for sure, a tragicomedy, and there are elements of the glib, the sensual, and the pure slapstick in it—but these days we tend to overemphasize these easy aspects of the tale and its telling. Furthermore, we think of the various rejections and bans and the generally shocked reception the book was given upon publication, and we mentally admonish our predecessors for their prudishness. We then make book jackets and other portrayals that are self-congratulatory in their sensuality or lack of gravitas. But are these representations of Lolita truly speaking on behalf of the book or, rather, some modern attitude toward mid-century mores? The more I think on it, the more I feel like this kind of jacketing solution for Lolita is false and pernicious in its own way. It is at best a misrepresentation, at worst a kind of whitewashing, and it does no justice to the text it putatively represents.4

§

“There seemed to be nothing to prevent my muscular thumb from reaching the hot hollow of her groin—just as you might tickle and caress a giggling child.”

Ick. It’s repulsive. But it is wonderfully alliterative. But still: ick. This is a child we are talking about here. Explicitly.

This dialectic is partly the point. If one examines the one sex scene we are privy to in full, this infamous lap scene, what is salient is that only one member of the couple is fully aware that a sexual act is transpiring. Lolita wiggles, squirms on her (soon-to-be) stepfather’s lap, and he achieves “the last throb of the longest ecstasy man or monster had ever known.”

Double ick.

It is the discordant lopsidedness of the encounter, in age as in awareness (in conjunction with the dual resonance of the lap as both the safe seat of childhood—the place where trust is implicit—and the intersection of sexual congress), that makes the scene rich, if still repugnant. This friction incriminates the reader, who is also, for reading the passage, in collusion, and now, like H.H., a “monster.” This incrimination, I would posit, is partly the point. We are complicit, we readers of Nabokov’s Lolita. We are witnesses to a crime; moreover, we are witnesses who are seduced by the crime, by its trappings, by the cadence of its sentences, by Nabokov’s genius, and we just can’t turn away.

Pretty depictions of softly lit Lolitas (anatomized or whole) on book covers seem to perform the opposite function: They downgrade our outrage and our complicity (and in so doing they also lessen the effect of the book’s central metaphor—but I’ll get to that anon). They are the cover-design analogue of porn stars in schoolgirl uniforms—there is no longer anything obviously discordant about them, as they are the fantasy fulfillment of a culture that has long since sexualized its young. We don’t see those plaid skirts and feel the frisson of an unusual juxtaposition. We see merely the vague promise of sex, if even that. The uniform in this case is just another symbol that has lost its original immediacy. And through repeated use it has become meaningless. It no longer represents innocence; thus, it cannot represent fallen innocence either.5

So what’s a designer to do?6 Does a designer attempt a (truly) shocking cover, in order to properly represent the ethical disquiet that Nabokov’s narrative provokes?

“She was shaking from head to toe (from fever) She complained of a painful stiffness . . .and I thought of poliomyelitis as any American parent would. Giving up all hope of intercourse . . .”

Groan.

In surveying the extant editions, I don’t see many that rise to the challenge. Perhaps the first edition had it right: the so-straight-it-must-contain-something-dangerous approach, otherwise known as the “brown-paper-wrapper gambit,” (which in this case is green).

Megan Wilson’s Lolita cover for the 1997 Vintage edition (3) is an interesting case—and stands as one of my all-time favorites. (Though let’s ignore the Vanity Fair quote, shall we? What could “The only convincing love story of our century” possibly mean?) When I first encountered this edition, I assumed our supposed Lolita’s pose was flirtatious. One knee bends in front of the other, almost as if in a curtsy. She seems locked in some sort of stylized sexual demurral. However, as time passed (and my reading of the text evolved), I began to factor in the stark, ominous lighting and the gaze of the photographer became threatening; the pose of the subject one of real discomfiture. The knee crosses protectively. What seemed to me at first as “come hither” has evolved into “please don’t.”

3. Lolita, American paperback edition (1997), Vintage International. Designer: Megan Wilson.

This conceptual cover (4) is satisfying (in its imagery at least) and comes pretty damn close to achieving the requisite unease I’ve been discussing, thanks to a stark visual double entendre. And yet, though clever, the jacket somehow feels too narrow in focus to be a proxy for Nabokov’s striking array of ideas. It performs its circumscribed task well, but it doesn’t capture the book’s gestalt.

4. Proposed cover design for Lolita (Aleksander Bąk).

5. Proposed cover design for Lolita (Peter Mendelsund). “We had breakfast in the township of Soda, pop. 1001.” —Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita.

Which leads me to my next point: Maybe it’s simply impossible to give this book the jacket it deserves, if one believes it deserves a representation of the central sexual relationship between a young girl and an older man.

But, as it turns out, this book is not actually about a deranged pervert lusting after a nymphet.7 I mean, it is, but it is clearly much more than merely that. Lolita’s central argument concerns the young and the old, but the Old World and the New World. As most of you know, Lolita is a book about America: a young, robust, bobby-socked, dewy-eyed, and apple-cheeked America, an America of “sweet hot jazz, square dancing, gooey fudge sundaes, musicals, movie magazines and so forth.” This is an America of license plates, motel-room keys, Coke bottles, chewing gum—a young, fresh, insolent, unaware America.

Lolita is the tale of a gentleman caller, one who hails from an exhausted continent as exhausted in its linguistics as it is in its literature, to adopt, as H.H. adopts his ward, a new language—to inhabit it, fetishize it, tyrannize it.8 Nabokov’s is a book about America and its language. Isn’t it?

§

Every book (or, rather, every good book) contends with a calculus greater than the mere facts of its narrative. If books were only drama-delivery systems, we’d have nothing to talk about in literature classes and Stephen King would be a Nobel Laureate.9 The facts of the narrative may keep us turning the pages, but it’s a book’s greater purpose, as it were, that makes it truly worthy of our attentions. We come for the literal, but we stay for the literary.

This much is obvious, but it raises an important question for designers of book jackets. We book-jacket designers are delegated the responsibility of representing a text—that is, unless we see ourselves as meager decorators of it.10 But assuming for the moment that we’ve taken on the task of representing the text rather than just adorning it, must we designers determine what a book is about before we design a jacket for it? When I’m reading a manuscript, I find I’m constantly on the lookout for images, characters, and ideas that can serve, metaphorically, as proxies for the whole. But a question is constantly emerging in my mind: Is this “whole” the narrative itself, in its literal details, or the thing(s) the narrative is driving toward—its greater underlying significance?11 Which is to say: Is it our job in the case of Lolita to represent “the central sexual relationship between a young girl and an older man”? Or are we being asked to delve deeper?12

Put another way, how impoverished would our book-design jobs be if we didn’t, as a rule, delve deeper? If we didn’t interpret? If we didn’t visually translate that which was most essential in a book? Our jobs would be sad indeed. And our jackets would be too. And Lolita, like all our covered texts, would be ill served.

6. Lolita, Brazilian edition (1994), Companhia das Letras.

1 Directly after I judged this Polish Book Cover competition, I was asked to participate in John Bertram’s excellent Lolita project, which eventually turned into this book. I’m not sure if this particular Lolita cover (1) would have resonated with me quite as much if this second assignment hadn’t come along.

2 These days, book jackets often revel in wit, conceptual deviousness, and unusual clever or droll juxtapositions. We, as a professional community, seem to have elevated the visual bon mot above all other virtues. I won’t delve into the “why” of the matter here for want of space, but suffice it to say that clever work is the work that is celebrated in our community. Not that wit in itself isn’t valuable and doesn’t have an appropriate place in design, but wit is not the same thing as insightfulness, and often insightfulness is what is called for in a book jacket. Our fetishization of cleverness has taken a toll, I believe, in that quite frequently these clever solutions work at cross-purposes to the (more often than not sincere) narratives they represent. A book whose author has gone out considerably on a limb in order to write in a genuine and unaffected fashion does not want a cover that winks at the reader. Wit, when it becomes compulsive (as anyone who has a friend who puns too often knows), quickly becomes its opposite—dullness, or predictability. Are we, as a professional community, that punning guy? I hope not.

3 Or could it be the work of a young H.H.?

4 Christopher Hitchens, describing his (and my own) mutating relationship with the narrative: “When I first read this novel, I had not experienced having a twelve-year-old daughter. . . . I dare say I chortled, in an outraged sort of way, when I first read, ‘How sweet it was to bring that coffee to her, and then deny it until she had done her morning duty.’ But this latest time I found myself almost congealed with shock.” Hitchens also judiciously reminds us that “immediately following each and every one of the hundreds of subsequent rapes, the little girl weeps.” Read that sentence again. Now survey again the treatments this book has been given. Feel the disconnect?

5 The book jacket that always springs to my mind when thinking of exhausted metaphors and their remedies is Chip Kidd’s brilliant design for Richard Lattimore’s translation of the New Testament. In lieu of yet another meaningless cross or crucifixion scene (divorced from any real notion of death, torture, or sacrifice), he gives us a photo of a real, actual, honest-to-goodness dead person. Offensive, you say? I counter that you are inured to the once vibrant meanings that underlie your sacred texts.

6 This is a good a time (i.e., sooner, rather than later) to mention that book designers are only partly responsible for the covers they produce, in the sense that their work has to pass muster with a marketing department as well as an editorial division (not to mention authors, agents, et al., all of whom must be appeased). It bears repeating that in attempting to sell a book, designers must, not always, but sometimes, pander to the very public I was just dressing down—a public that on occasion lacks the interpretive subtlety to parse literary subtext. That is to say, if the general reading public expects a schoolgirl or schoolgirl uniform on a Lolita jacket, then book buyers and book sellers will also be expecting a schoolgirl or schoolgirl uniform on a Lolita jacket; and one can then reasonably assume marketing departments in publishing houses will want them as well. In the end, going backward, upriver toward its source, even editors begin to take their cues from misinformed readers at large. A good friend who is a multiple best-selling author was once told by his editor that his latest work wasn’t up to snuff because it “didn’t seem enough like the kind of thing” he writes. In other words, there are times when even authors cannot beat back the tide of their own marketing expectations. (Dead authors have no say in this process, which is one reason we designers love them as much as we do.) In any case, managing these expectations is, sadly, also part of our jobs as jacket designers.

7 I am aware that about is a tricky word. We’ll get to that in a minute.

8 “Even Lolita, especially Lolita, is a study in tyranny.” —Martin Amis, Koba the Dread

9 For the record, I am a big fan—just not for the same reasons that I am a fan of, say, James Joyce.

10 I often find in my own work that decorating a book jacket is a more efficacious approach than attempting to represent or explain its meaning.

11 ABOUT-NESS: It is extremely complicated to explain what one means when one says that a book is “about” something or other (difficult because the word about is hard to define; difficult in the sense that most good books proffer more than one central argument; and difficult, especially difficult, in the wake of the putative “death of the author,” Barthes, Saussure, Derrida, pluralities of meaning, and nearly fifty years of intertextuality, et cetera).

And yet . . .

What I call “the cover-design test” would be useful in Comp Lit class discussions: i.e., if your theory of meaning (Marxist, post-structuralist, feminist, Freudian, postcolonialist) cannot translate into a commercially viable book cover, then it fails at properly describing your text. (For instance, what would Roland Barthes have envisaged for the cover of Balzac’s Sarrasine, the subject of his structuralist analysis in S/Z? I would posit that this imaginary jacket would be a catastrophe, as his famous interpretation of the text was highly idiosyncratic and personal.) All of which is to say that I believe there is more consensus around what books are “about” than most may think. We designers, with our jackets, attempt to capture meaning that is not exactly consensus driven, but rather that is both true enough, and flexible enough, that most readers won’t find it a stretch to believe it. That is to say, we are trying to maximize understanding. In this sense, jacket design is a kind of interpretational utilitarianism.

explain its meaning.

12 Ultimately, this question—of what we designers ought to be doing on behalf of the reader, the author, and the entire publishing endeavor—is too complex to unpack here.