Duncan White

In 1963, Umberto Eco collected some of the pastiches and parodies he had written for his column in the literary magazine Il Verri into a book. This book, named Diario Minimo, after the column, was translated into English as Misreadings in 1993 and opened with “Granita,” a parody of Lolita. Eco writes in the preface that the piece was “not so much a parody of Nabokov as of the Italian translation of his novel.” As a result, Lolita—and Lolita—underwent some remarkable changes on the journey. In Eco’s version, Umberto Umberto, in high Humbertian tones, describes his obsession not with nymphets but with “nornettes”:

What can you know of the subdued, shadowy, grinning hunt that the lover of nornettes may conduct on the benches of old parks, in the scented penumbra of basilicas, on the gravelled paths of suburban cemeteries, in the Sunday hour at the corner of the nursing home, at the doors of the hospice, in the chanting ranks of parish processions, at charity bazaars: an amorous, intense, and—alas—inexorably chaste ambush, to catch a closer glimpse of those faces furrowed by volcanic wrinkles, those eyes watering with cataract, the twitching movement of those dry lips sunken in the exquisite depression of a toothless mouth, lips enlivened at times by a glistening trickle of salivary ecstasy, those proudly gnarled hands, nervously, lustfully tremulous, provocative, as they tell a very slow rosary!

Eco’s mischievous heresy is cut short (his narrator’s manuscript, found in a Piedmont prison, has been eaten by rats) immediately after Umberto’s moment of revelation: the appearance of Granita with her “lasciviously white locks.”1 To call this a “misreading” of Lolita is something of an understatement, but within the playfulness of the exercise Eco has a serious point, as all good parodists do. In perverting the perversion, he takes us back to our original resistance to what is a lyrical description of the sexual abuse of a child.

Eco’s parody is particularly astute in how Umberto itemizes the physical temptations of his ideal nornette, reflecting Humbert’s own descriptions of Lolita. The first forty pages of Nabokov’s novel work up to Humbert’s first meeting with Lolita, on Charlotte Haze’s “piazza.” Until then, the reader’s expectations are guided by vague descriptions of Lolita’s precursor, Annabel Leigh, who is remembered indistinctly:

There are two kinds of visual memory: one when you skillfully recreate an image in the laboratory of your mind, with your eyes open (and then I see Annabel, in such general terms as: “honey-colored skin,” “thin arms,” “brown bobbed hair,” “long lashes,” “big bright mouth”); and the other when you instantly evoke, with shut eyes, on the dark innerside of your eyelids, the objective, absolutely optical replica of a beloved face, a little ghost in natural colors (and this is how I see Lolita).

This optical replica can only be painted on the inner side of Humbert’s eyelids. He, famously, has “only words to play with”; in prison he regrets not having kept any photographs of Lolita and, more keenly, not having filmed her while she played tennis. No matter how Humbert tries to evoke Lolita, the limitations of language prevent him from recalling her completely. Here is his description of that first meeting on the piazza:

Without the least warning, a blue sea-wave swelled under my heart and, from a mat in a pool of sun, half-naked, kneeling, turning about on her knees, there was my Riviera love peering at me over dark glasses.

It was the same child—the same frail, honey-hued shoulders, the same silky supple bare back, the same chestnut head of hair. A polka-dotted black kerchief tied around her chest hid from my aging ape eyes, but not from the gaze of young memory, the juvenile breasts I had fondled one immortal day. And, as if I were the fairy tale nurse of some little princess (lost, kidnapped, discovered in gypsy rags through which her nakedness smiled at the king and his hounds), I recognized the tiny dark-brown mole on her side. With awe and delight (the king crying for joy, the trumpets blaring, the nurse drunk) I saw again her lovely indrawn abdomen where my southbound mouth had briefly paused; and those puerile hips on which I had kissed the crenulated imprint left by the band of her shorts—that last immortal day behind the “Roches Roses.” The twenty-five years I had lived since then, tapered to a palpitating point, and vanished.

Humbert is imprisoned by syntax, forced to map out Lolita’s body one part at a time in what Jenefer Shute has called “the cartography of desire” (“So Nakedly Dressed”). If Shute is correct in arguing that Lolita has “not yet constituted herself as an object of visual consumption,” then her sexuality must be in the eye of the “aging ape” who beholds her. An objective Dolores Haze cannot exist in the novel; she is only ever seen through Humbert’s solipsistic prism, only ever constructed through his language. Even the name Lolita is Humbert’s distortion of the “real” Dolores, a rhetorical strategy he uses to stake a proprietary claim over her. As Humbert writes after molesting her for the first time: “What I had madly possessed was not she, but my own creation, another fanciful Lolita—perhaps, more real than Lolita; overlapping, encasing her; floating between me and her and having no will, no consciousness—indeed no life of her own.”2

Accordingly, representing Lolita on the cover of the novel becomes an ethical challenge. If we give her a life of her own, we are asking that she no longer be read through Humbert. For instance, do we believe Humbert’s claim of the first time they have sex, that “it was she who seduced me”? The way she is depicted on the cover can influence our reading—the book exerts an influence on the novel.

Lolita has been repeatedly misread on the cover of Lolita, and frequently in a way to make her seem a more palatable subject of sexual desire. Take, for example, the color of her hair. When Nabokov gave exams to his students at Cornell, this was exactly the kind of question he would ask. In his exam on Madame Bovary, he would ask them to “describe Emma’s eyes, hands, sunshade, hairdo, dress, shoes.” That hairdo, Nabokov felt, had been “so dreadfully translated in all versions that the correct description must be given else one cannot visualise her correctly.”). For a translator to dishevel Emma Bovary’s hairdo was, for Nabokov, an act of aesthetic vandalism, distorting the details out of which the work is constructed. What, then, of visualizing Lolita correctly? Humbert describes twelve-year-old Lolita as sporting a bob of “chestnut brown hair”; this is a very different creature from the paratextual representation of Lolita as a late-adolescent blonde.3 In the novel, Lolita is first corrupted by Humbert, forced eventually into a kind of domestic prostitution, before running off with Clare Quilty and undergoing a second corruption at his ranch.

Lolita undergoes still another corruption on the cover of the novel. The dyeing of her hair is emblematic of the transformation she has undergone in what one might call the book’s public imagination. (I have in mind here Gérard Genette’s definition of a book’s “public” being wider than its actual readership.) The point of departure was clearly Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film and its poster, depicting Sue Lyon in heart-shaped sunglasses enjoying a lollipop. This Lolita has not been shaped by the eye of Humbert or Nabokov but by extratextual forces and, over the last five decades, has beckoned as a false siren from the cover of numerous editions of the novel.

Why should this matter? After all, the textual Lolita would not seem to be altered in any way, and very few of Nabokov’s contemporaries had any sort of influence over the cover of their books.4 The use of book jackets dates to the 1820s, but “until late in the century they had only been used as protective packaging and tended to be non-pictorial, labelled wrappers with little focus on design,” Ned Drew and Paul Sternberger relate in By Its Cover, their 2005 history of American book-cover design. In the 1890s blockings of books began to be decorated, a practice that moved to dust jackets in the early twentieth century and finally to the covers of paperbacks. The first books to consistently use cover decoration were children’s books, which were often illustrated by the same artist as the books themselves were; Nabokov’s Russian translation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, Anya v Strane Chudes, which was released in 1923 by the Gamaiun Publishing House, in Berlin, had a cover design and illustrations by A. S. Zalshupin. Nabokov’s Russian novels had, with the exception of the film-strip-illustrated Kamera Obskura (1933), been published with standard, unadorned paper covers.

The situation changed when Nabokov moved to the United States. As shown by his correspondence with his various publishers, Nabokov cared about how his books were put together and would fight to get as much control as possible of what Genette calls a book’s “peritext”—the paratexts that are physically part of the book. This was partly to do with his personal aesthetics (he could not bear to see his book encased in “vulgar” covers) but also because, from Despair and The Gift through to his American work, he created novels that mimicked books. Lolita, with its fictional foreword by John Ray, Jr., Ph.D., is no exception. Nabokov used as much of his books as possible for his artistic purposes—the index of Pale Fire, the family tree and blurb of Ada—and often trespassed on the territory of the publisher in the process. When he could, he would demand to see jacket illustrations before publication and frequently vetoed those he thought to be unsuitable. For the 1963 Penguin edition of Invitation to a Beheading and the 1966 Panther edition of The Gift, Nabokov persuaded his publishers to use the designs he had collaborated on with his son, Dmitri. This fuzzed the lines between what was Nabokov’s composition and what was not, and made him complicit in the production of the book as a whole.

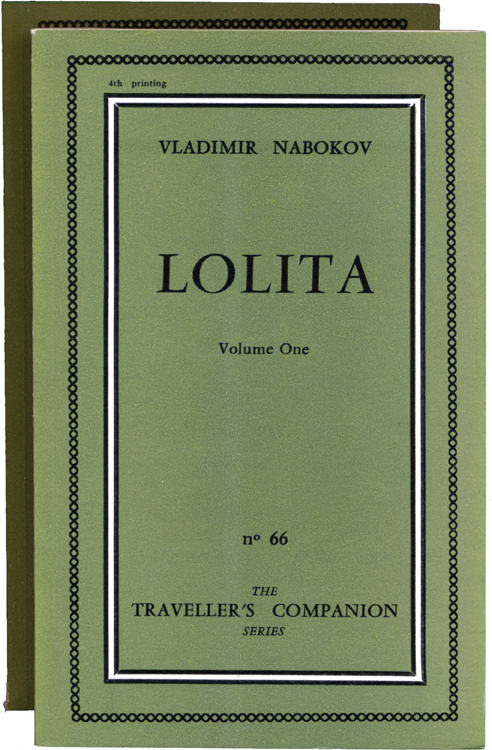

While one must take into account Nabokov’s desire to avoid censorship, his dealings with Lolita’s American publisher suggest that he was sensitive to the problem of authorial complicity in any depiction of Lolita. When Maurice Girodias published Lolita in 1955 in Paris, it came out with the characteristic green covers of the Olympia Press, without illustration (1). Three years later, when it came to the American edition, Nabokov repeatedly insisted to Walter Minton of Putnam’s that there be no girls in the cover art. In a March 1, 1958, letter, Nabokov wrote:

1

What about the jacket? After thinking it over, I would rather not involve butterflies. Do you think it could be possible to find today in New York an artist who would not be influenced in his work by the general cartoonesque and primitivist style jacket illustration? Who would be capable of creating a romantic, delicately drawn, non-Freudian and non-juvenile, picture for LOLITA (a dissolving remoteness, a soft American landscape, a nostalgic highway—that sort of thing)? There is one subject which I am emphatically opposed to: any kind of representation of a little girl.

That emphatic opposition is repeated in a letter of April 23, after Nabokov had received some sample cover art:

I have just received the five designs and I quite agree with you that none of them is satisfactory. . . . I want pure colours, melting clouds, accurately drawn details, a sunburst above a receding road with the light reflected in furrows and ruts, after rain. And no girls. If we cannot find that kind of artistic and virile painting, let us settle for an immaculate white jacket (rough texture paper instead of the usual glossy kind), with LOLITA in bold black lettering.

It is clear from these two letters that Nabokov wanted a depiction of an American landscape on the cover. Alfred Appel writes in his annotations to the novel that when he asked Nabokov about reviewers who found anti-American aspects to Lolita, Nabokov urged him to note the “tender landscape details.” Not only did this resonate with Nabokov’s attitude to his novel but it also solved the ethical problem of using an image of Lolita.5 Putnam’s did not share Nabokov’s enthusiasm for a landscape on the cover and instead opted not to use any kind of illustration. Brian Boyd writes that on receiving an advance copy of the Putnam’s edition, Nabokov “was pleased with the book’s discreet cover—lettering only, no picture of a little girl—and Putnam’s discreet publicity” (2).

2

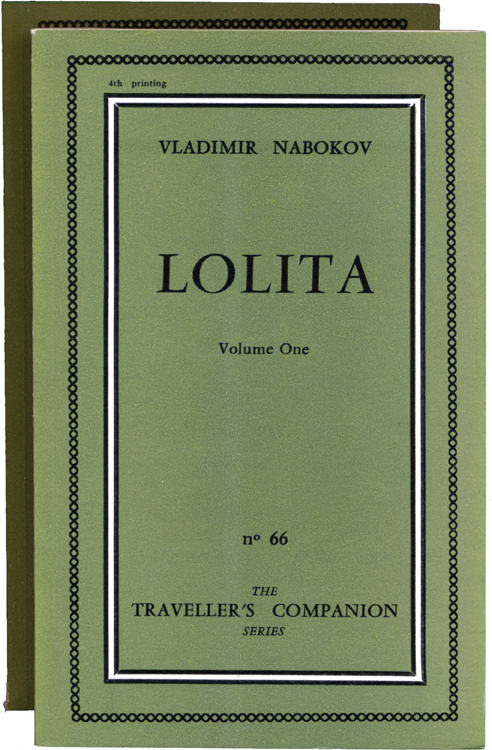

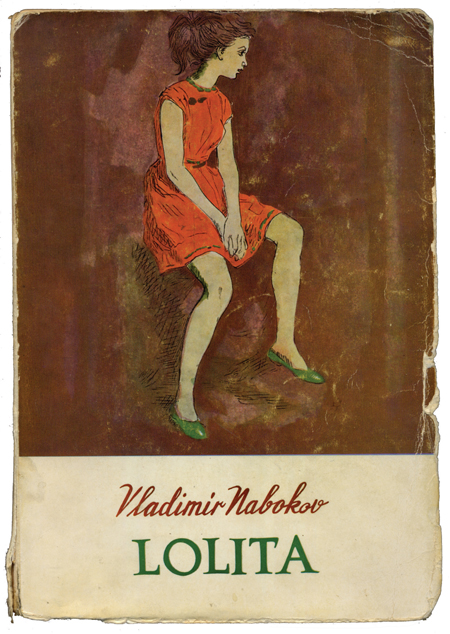

Nabokov’s ability to control the way Lolita was published would not last. In a 1965 documentary, Nabokov is shown perusing his bookshelf of various translations of Lolita. One of his favorites is the “remarkably pretty edition” produced by Gallimard’s Livre de Poche series in 1963, which he finds “delightful” for how it playfully depicts Lolita on the front cover, with the back of her head on the back cover (3). Elsewhere, Nabokov praised the “perfectly enchanting” Dutch first edition, which has Humbert’s ominous presence in the foreground (4).6

3

4

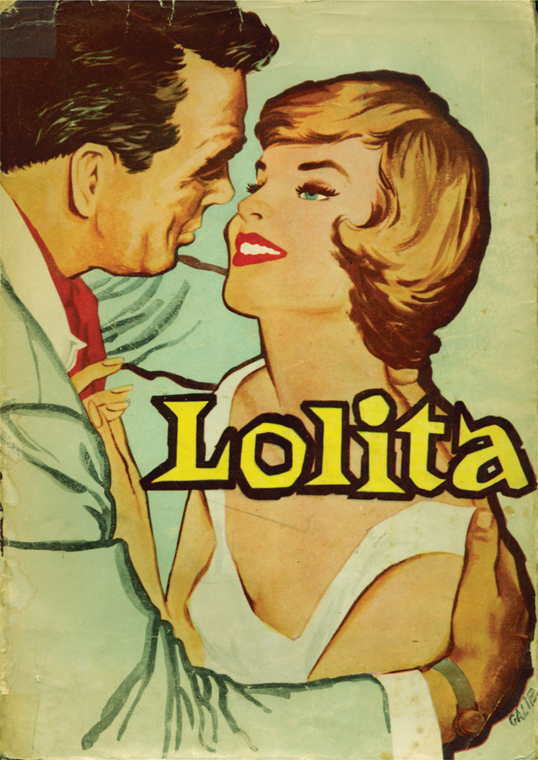

But for the most part, Nabokov despaired of the way Lolita was depicted on subsequent covers of his novel. In the 1959 letter to George Weidenfeld in which he praised the Dutch design, Nabokov also expressed his horror at the “horrible young whore” on the cover of the Swedish edition (5). In the documentary, he seems baffled but amused by the “extraordinary” 1959 Turkish edition (6). (“I am not sure who is older,” he says as he holds up a cover showing Humbert and Lolita embracing.)

5

6

In the afterword to Lolita, Nabokov writes that pornography “connotes mediocrity, commercialism and certain strict rules of narration,” all of which surely apply to the conventional misreading the book has gotten through its covers. Publishers found it difficult to resist cashing in on the novel’s salacious reputation, even if it meant a kind of self-censorship, transforming Lolita into a more acceptably desirable figure. With the novel’s success, Nabokov soon felt himself losing control of how Lolita appeared. In a 1976 letter to Philip Oakes about a new English edition, the year before his death, Nabokov’s resignation is clear:

The pictures by Ovenden of that young sea-cow posing as my Lolita are, of course, preposterous, and the Academy Editions’ plan to publish them has not received my blessing. Yet there is nothing much I can do about it. Recently I was shown an advert in an American rag offering a life-size Lolita doll with “French and Greek apertures.”7

In this light, Eco’s misreading of Lolita is no more preposterous than many others. In 1992, a 17-year-old named Amy Fisher shot her older lover’s wife and swiftly became known by the New York Post as the “Long Island Lolita.” Alexander Dolinin has shown that the real case of the abduction of Florence Sally Horner by Frank LaSalle in 1948 informed Nabokov’s composition of Lolita, but through the looking glass, victim has become perpetrator. In Nabokov’s novel, Humbert exploits Dolores Haze to create his Lolita, abducting her, bullying her, raping her. Yet outside the novel, the extratextual Lolita image has not just been exploited to sell books but has reached the depressing consummation of its trajectory as a sex toy and media shorthand for a teenage murderer.

It is Humbert, of course, who casually informs the reader that “you can count on a murderer for a fancy prose style,” and there is much misdirection in the novel, leading the reader to suspect that Humbert will murder Lolita at its conclusion. Humbert makes it clear that if we are reading the manuscript and his wishes have been met, then Lolita is dead—he made it a condition of publication. In Ray’s foreword, Nabokov reveals to the second-time reader the death of “Mrs Richard F. Schiller” during childbirth. Martin Amis writes that “the presiding image of Lolita, so often missed by the first-time reader (I know I missed it, years ago), is adumbrated in its foreword: Lolita in childbed, dead, with her dead daughter.” In the final paragraph of his manuscript, Humbert explains his motive for killing Clare Quilty and writing his “confession”:

One had to choose between him and H. H., and one wanted H. H. to exist at least a couple of months longer, so as to have him make you live in the minds of later generations. I am thinking of aurochs and angels, the secret of durable pigments, prophetic sonnets, the refuge of art. And this is the only immortality you and I may share, my Lolita.

As the history of the covers of Lolita attests, not all pigments are durable and one cannot be too careful when anticipating one’s immortality. Perhaps the illustrators of the more gaudy covers were unaware that they were adding a few years to make Lolita a more palatable age, or that they were dyeing her hair to match Hollywood’s tastes, but there is no question that these covers ignore the essentially elegiac quality of the novel. Lolita would never live to the age of Granita. The girl or woman staring out of the cover with her chestnut bob or blonde bangs is, in Amis’s words, “dead on arrival, like her child.”

1 Eco gives a précis of the rest of the action, derived from surviving fragments, including Umberto’s abduction of Granita on the handlebars of his bicycle and the climactic shoot-out with his Quiltyesque rival at a Boy Scout camp.

2 Humbert has a point; the only time a different voice has the opportunity to describe Lolita is in John Ray’s preface, and he simply tells us that she “died in childbed, giving birth to a stillborn girl.”

3 See for example the 1966 and 1969 Mondadori (Italy) editions and the 1969 and 1973 Corgi (U.K.) editions. Many more have reproduced the iconic movie-poster photograph of Sue Lyon. The less said about the 1970 Dutch Omega edition and the 1974 German Gutenberg editions the better.

4 Powers notes a few exceptions. T. S. Eliot with Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (1939) and Evelyn Waugh with Love Among the Ruins (1962) sketched designs for their covers while the cover of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1927) was designed by her sister Vanessa Bell, and published by Woolf herself, in partnership with her husband Leonard, for the Hogarth Press. For The Hobbit, J.R.R. Tolkien “drew his own jacket, with a stylized art nouveau landscape and runic lettering around the border.”

5 Nabokov’s choice for an American landscape has its source within the novel itself. For Lolita’s fourteenth birthday, Humbert buys her A History of Modern American Painting, trying to “refine [her] pictorial qualities,” and recommends the work of Peter Hurd. Hurd’s painting The Dry River strongly resembles the kind of landscape Nabokov recommended to Minton. Boswell’s book is also exploited by Nabokov to deepen the narrative allusions to Quilty. When consulting the book, Lolita, unimpressed by Hurd and Grant Wood, demands “to know if the guy noon-napping on Doris Lee’s hay was the father of the pseudo-voluptuous hoyden in the foreground.”

6 Alan Powers illustrates the transition from discretion to titillation on Lolita covers in Front Cover.

7 After Nabokov’s death, jacket designers have tried to push the limits of the taboo about depicting the sexuality of a young girl. The initial design of the Penguin fiftieth anniversary edition of the novel by the art director John Gall had a pair of lips rotated to the vertical axis. If the paratext is, as Borges would have it, the vestibule to the book, one wonders what exactly one is being invited to enter. While the image was still used in promotional material, the design was felt too explicit and the lips were rotated back to the horizontal for publication.

Bibliography

Amis, Martin. Introduction. Lolita. London: Everyman, 1992.

Boyd, Brian. Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1991.

Dolinin, Alexander. “What Happened to Sally Horner: A Real-Life Source of Nabokov’s Lolita.” Times Literary Supplement, September 9, 2005, pp. 11–12.

Eco, Umberto. Misreadings. Trans. William Weaver. London: Picador, 1993.

Genette, Gerard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997.

Nabokov, Vladimir. The Annotated Lolita. Ed. with preface, intro., and notes by Alfred Appel, Jr. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 2000.

_______. Lectures on Literature. Ed. Fredson Bowers. New York: Harvest/HBJ, 1980.

_______ . Selected Letters: 1940-77. Eds. Dmitri Nabokov and Matthew J. Bruccoli. New York: HBJ/BCL, 1989.

Powers, Alan. Front Cover: Great Book Jacket and Cover Design. London: Octopus Publishing Group Ltd, 2001.

Shute, Jenefer. “ ‘So Nakedly Dressed’: The Text of the Female Body in Nabokov’s Novels.” Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita: A Casebook. Ed. Ellen Pifer. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.