John Bertram and Yuri Leving

Fifty-eight years after Lolita was first published, Vladimir Nabokov’s most famous novel remains firmly in the public consciousness, but more often for its misunderstood subject than for its masterful and dazzling prose. The character of Lolita, in her innumerable pop-cultural refractions (Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of the book is primary among them, but there are also a failed 1971 musical; a 1992 Russian-language opera; a second film, from 1997; a 1999 ‘retelling’ from Lolita’s point of view; and a recent one-man show1), has come to signify something very different from what Nabokov presumably intended. But although she has acquired this misleading advance guard, the novel itself remains as potent as ever. At turns sad and hilarious, deeply disturbing and insanely clever, Lolita is an immensely rich reading experience. Still, if there ever were a book whose covers have so reliably gotten it wrong, it is Lolita. This book explores why this is so.

Lolita—The Story of a Cover Girl has its genesis in “Covering Lolita,” Dieter E. Zimmer’s online gallery of close to 200 of the novel’s covers, spanning nearly six decades of its international publishing history.2 Though it is intriguing to see them arrayed together, and amusing to follow the choices made by the designers, illustrators, and publishers, it is apparent how few of them ultimately succeeded at communicating the depth and complexity of the novel. Overflowing with powerful, finely wrought imagery, Lolita also strikes with darkness and brutality. Ellen Pifer, editor of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita: A Casebook (Oxford University Press, 2003), describes it starkly as “a threnody for the destruction of a child’s life.”3 It is difficult to think of another book whose cover design has been as fraught with peril.

There are several factors that make Lolita such an instructive case for investigating the art of cover design. First, dozens of existing covers are available for study. Furthermore, Nabokov was not only interested generally in the covers of his books but, in particular, voiced strong opinions about how Lolita’s cover should and shouldn’t appear. (Although, as Zimmer notes in his essay, included in this collection, Nabokov’s opinion evolved over time.) Nabokov wrote with great care and specificity, believing that what may appear to be textual minutiae are often crucial to a full understanding and appreciation. The publisher that chooses for its cover of Lolita a girl with long blond hair or a woman of 21 may not care about such matters. After all, “fidelity to the novel’s narrative has not been high on the list of publishers’ concerns.”4 This is one reason why misunderstandings and misinterpretations of Lolita still persist. It’s easy to see why a prospective reader, even at this late date, would assume that the titular character is the precocious seductress that her name has popularly (and unfortunately) come to signify.

Duncan White writes that “Lolita has been repeatedly misread on the cover of Lolita, and frequently in a way to make her seem a more palatable subject of sexual desire.”5 Kubrick’s 1962 film, with its maddeningly indelible image of Lolita (played by the actress Sue Lyon), is arguably the primary source of this interpretation. Ellen Pifer calls it “a blatant misrepresentation of Nabokov’s novel, its characters, and its themes. Not only does it betray the nature of the child featured in its pages; it disregards the way that the narrator, Humbert Humbert, comes to terms with his role in ruining her life.”6 But however misleading it was, the movie—along with Adrian Lyne’s 1997 film adaption—influences our understanding of the novel to this day, especially since its images have been used unsparingly for decades to promote the book.

Playboy’s Miss November 2012, Britany Nola, was born in 1991, and the book she loves most, the magazine reveals, is Lolita. One presumes that she has read it and not simply watched Lyne’s film, made before Nola herself was of nymphet age. (“[The] man of my dreams is Jeremy Irons,” Nola is quoted as saying in the magazine. Irons, of course, played Humbert in that 1997 movie.)

What makes Nabokov’s novel immortal and its subjects perpetually relevant, especially in popular culture? In recent years there has been an explosion of Lolitamania in pop music. While putting together a Nabokov syllabus for the 2012 semester, a colleague of ours decided on a whim to compile a Spotify playlist of songs that have “Lolita” in the title. He gave up after the playlist reached nearly a hundred songs—over five hours of music.7 The most commercially successful of the current crop of Lolita-inflected artists is Lana Del Rey (born Lizzy Grant, in 1986), whose 2012 debut album, Born to Die, sold over two million copies worldwide within six months of its release. This American singer-songwriter’s carefully constructed public image is a blend of nymphet and femme fatale transported from the 1950s and 1960s into today. Several of Del Rey’s songs pay homage to Nabokov. Critics have noted that “Off to the Races,” for instance, “cleverly combines tropes straight out of Nabokov with those straight outta gangsta rap. . . . ‘Light of your life, fire of your loins,’ Del Rey purrs, just like Lolita’s Humbert Humbert, mixing the old-school Hollywood glamour of her vocal with mixtape-ready nods to cocaine and Riker’s Island.”8 Significantly, Del Rey visually models herself on the Lolita from Kubrick’s movie (or, rather, from its iconic poster, which visually influenced subsequent print editions of Nabokov’s Lolita; 1 and 2).

1 and 2. Lana Del Rey evoking Lolita.

Del Rey appears to be the latest in a line of recent female pop-culture figures whom Meenakshi Gigi Durham described in her 2008 book, The Lolita Effect, as “promoting inappropriately hypersexualized clothing to grade-school girls over the world.” Durham examines a long list of “Lolitas” of our time, whom she defines as “deliberate sexual provocateurs, turning adults’ thoughts to sex and thereby luring them into wickedness, wantonly transgressing our basic moral and legal codes.”9 These girls are commonly presented as consenting participants in their own sexual exploitation.

In Chasing Lolita, Graham Vickers writes that “Lolita herself was eventually to become an enduring object of interest for reasons that were rarely literary.”10 Take, for instance, the “counterfeit Lolita fashion,” which Vickers argues was a media creation; heart-shaped sunglasses “had nothing whatever to do with the Lolita that Nabokov had realized in such precise detail and diligently accoutred with all those faded blue jeans, plaid shirts, tartan skirts, gingham frocks and sneakers.”11 This does not prevent fashion companies and their marketing departments from exploiting imagery indebted to Kubrick’s Lolita in selling their products to a young audience (3 and 4).

3. A 2010 Aldo campaign with a teenage model in suggestive poses.

4. A 2012 Aldo campaign used Kubrick-style Lolita imagery.

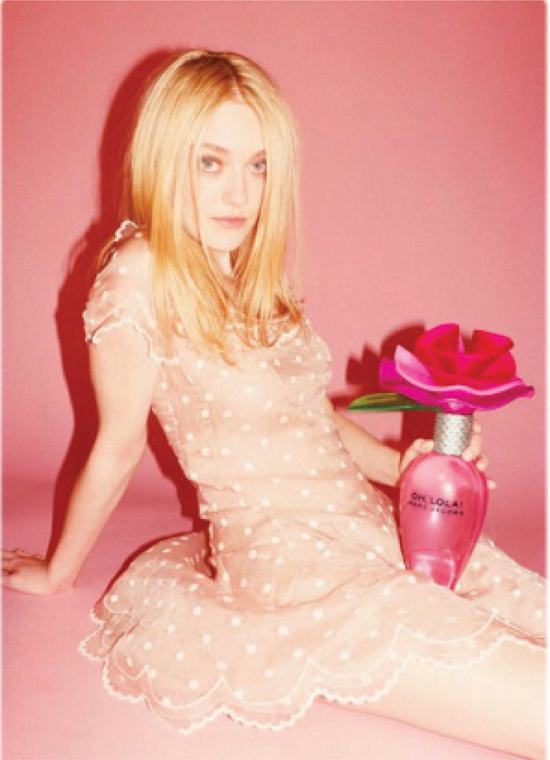

Sue Lyon’s heart-shaped sunglasses have become a “loose trademark”12 that signify a young, sexually available girl. Her image is everywhere, in television programs, movies, magazine stories, and especially in advertising. Debra Merskin has noted a number of consumer products “named after the literary vixen and celluloid coquette: ‘Lolita Lempicka’ fragrance, ‘Lolita’ leggings in a recent Nordstrom catalogue, or playing on words, ‘Nolita’ hair care products with the subheading ‘no limits, no boundaries.’ ”13 Although Lolita Lempicka is named after a French fashion designer and perfume creator, the link to its literary namesake is implied in its prurient ads (5). Among the latest manifestations of the trend is the Marc Jacobs perfume Oh, Lola! An advertisement for it, featuring a then seventeen-year-old Dakota Fanning, was banned in the U.K. in 2011 (6).

5. An advertisement for Lolita Lempicka fragrance.

6. A 2011 advertisement for the Marc Jacobs Oh, Lola! perfume.

The sexualization of children, particularly of girls, in fashion advertising is disturbing, but here Nabokov’s art continues to be confused with its imitations. Take “Hello, Dolly,” a Cosmopolitan fashion feature from 2005. “Little-girl-playing-dress-up frocks are rocking fashion right now,” the magazine copy reads. “They’re playful and whimsical—with the perfect amount of tongue-in-cheek naughtiness.” The painting hanging above the frolicsome young model features—of course!—butterflies (7).

7. A page from a 2005 Cosmopolitan fashion feature.

Recently, a stage version of Lolita by the American playwright Richard Nelson planned for St. Petersburg—Russia’s second-largest city and Nabokov’s hometown—was canceled over concerns that it could provoke public disorder. The performance was withdrawn following a letter signed by a handful of residents protesting the show and alleging that it ran afoul of a new antipedophilia law.14 Russians threatened to picket the show if it went ahead, and the theater’s administration succumbed to the pressure. The law, which penalizes “the propaganda of homosexuality and pedophilia among minors,” imposes fines of approximately $16,000 on individuals and $160,000 on organizations found to have breached it. But this absurd Puritanism is hardly a uniquely post-Soviet phenomenon. Only three years ago, a number of popular Penguin titles were pulled from Australia Post retail outlets—including The History of Sexuality, The Delta of Venus, and Lolita—after customers complained.15 To look at the books’ covers, it was likely the provocative design of the Penguin series that alarmed the consumers more than the books’ content.

By now, the cultural turmoil surrounding Lolita has little to do with Nabokov’s golem-like creation. But authors have been struggling for control over how their work is visualized since at least the early twentieth century, when pictorial editions became popular. And once writers entered the consumer-driven market of popular magazines, their aesthetic preferences became largely irrelevant. According to Edith Thornton’s study, “their texts slid into a vast network of visual cues, sales strategies, and competing discourses whose aims and intentions were under no one’s sole control. Magazine professionals intervened in established reading practices by exploiting parts of this network, and their maneuvers demonstrate how the reading experience changes with its context.”16 For this reason, Lolita—The Story of a Cover Girl is more than just an account of one novel’s visual history. It is a book about the publishing industry and advertising, about art and design, about creativity and inspiration.

Is a cover responsible for fairly representing the book? Taking it a step further, can a cover be said to have a responsibility to a fictional character, particularly one who has been abused and victimized as Lolita has? When might a cover incorporate images that are not supported by the text, and what problems could arise with such an approach?

These questions are complicated because what we know of Lolita comes from Humbert, the epitome of the unreliable narrator, charming and devious in the masterful subterfuge that is his “confession.” Many have noted that Humbert, preferring the idealization of his obsession, is largely oblivious to Lolita’s qualities as an autonomous human being—and, since she is a child, these are qualities that are still being formed. We, in turn, dependent on Humbert’s words, ultimately learn little about Lolita. Perhaps the alternate title—“Confession of a White Widowed Male”—mentioned in the fictional John Ray, Jr.’s, foreword should have been the primary title of the book. Or perhaps there is no woman in the text at all. One sophisticated response would be to create a cipher instead of depicting a girl, which is what Hilary Drummond has done—a synesthetic translation of cover text into color, based on the chromatic alphabet that Nabokov described in Speak, Memory and the colors that Jean Holabird assigned them in Vladimir Nabokov: Alphabet in Color (Berkeley: Gingko Press, 2005). In Drummond’s design, the colors (placed against a flesh-tone background) spell out “Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov” (8).

8. A design by Hilary Drummond that translates the cover text into Nabokov’s chromatic alphabet.

In various ways, the essays in this collection address issues of design and explore deeper avenues of investigation into Nabokov’s novel based on visual perception. As the designer Peter Mendelsund argues:

In attempting to sell a book, designers must, not always, but sometimes, pander to . . . a public that on occasion lacks the interpretive subtlety to parse literary subtext. That is to say, if the general reading public expects a schoolgirl or schoolgirl uniform on a Lolita jacket, then book buyers and booksellers will also be expecting a schoolgirl or schoolgirl uniform on a Lolita jacket; and one can then reasonably assume that marketing departments in publishing houses will want them as well. In the end, going backward, upriver toward its source, even editors begin to take their cues from misinformed readers at large.17

Dieter E. Zimmer’s essay “Dolly as Cover Girl” explores decades of Lolitas in the publishing world. Ellen Pifer brings clarity to Lolita the child, drawing her youth and helplessness into sharpest relief while uncovering the novel’s theme of democracy and its ideals: the freedom, equality, and justice of which Lolita is herself deprived. Duncan White concentrates on the importance of defining Lolita and argues that misrepresenting her poses the risk of misunderstanding the book to the point that we “ignore the essentially elegiac quality of the novel.”18 Further afield, Paul Maliszewski reconstructs the cover iconography of the multitude of paperback editions of Nabokov’s work that have appeared over the years, noting not only the writer’s interest in the details of the covers but also the influence of his late son, Dmitri Nabokov. Stephen H. Blackwell focuses on Nabokov’s brilliance in marketing his works as well as himself, presenting a picture of the author as an acutely aware and savvy PR man—“a brilliant actor” who succeeded, to a great extent, in shaping his own public image by controlling “texts, book covers, and translations as fully as possible.”19 Blackwell notes that “Lolita served as [Nabokov’s] best publicity coup—perhaps to a greater extent than even he could have imagined.”20 Yuri Leving discusses material from his personal collection of pirated Russian-language editions of Lolita. Alice Twemlow reflects on the covers that were commissioned for this book from the point of view of design criticism. The art director and graphic designer John Gall, perhaps best known for his own Nabokov covers (including that of the current American version of Lolita), discusses the challenges of designing a cover for such a complicated and controversial book. Peter Mendelsund, also a noted art director and book designer, wrestles with how to represent difficult books visually, Lolita chief among them. In a graphics-based essay, the Women’s Design + Research Unit (Siân Cook and Teal Triggs) considers Lolita from a design standpoint, comparing imagery from the novel with that of the film and a promotional photo shoot for the film. Barbara Bloom examines the use of book covers in her own work as an artist. These essays frame the larger milieu in which Lolita appeared and trace the many forces that acted on the visual representation of the novel.

The gallery of commissioned covers that comprises the heart of this book explores Lolita in original ways through a variety of lenses. Beyond the need to identify its contents and protect its pages, the contemporary book cover is a marketing tool enlisted by the publisher to sell a book, using typography and imagery to woo potential readers. The book cover is also paratextual material that has the potential to influence the reading of a text: It may distort or illuminate, editorialize, and even invent subjects and situations that do not exist in the text. In recent years, graphic design has become a subject of keen interest and exploration, expanding well beyond those in the field and the small population of aficionados. As a result, more people are paying close attention to design, placing significantly more emphasis on book covers. By extension, this puts more responsibility on designers and publishers to provide covers with a greater degree of fidelity to their books’ contents.

The designers of these mock covers for Lolita were given no instructions and had no requirements other than the dimensions and orientation. (Even these were arbitrary, intended only to regularize the display of covers and to facilitate the design of this book.) Freed from marketing constraints and the need for the covers to actually sell books, the designers were able to delve into the novel’s subject matter, pursue more obscure avenues, and, in some cases, take approaches of visual commentary. The resulting glosses and marginalia illuminate the novel in clever ways. Subtle and coarse, reverent and sly, sometimes (but not always) following Nabokov’s oft-cited and later rescinded “no girls” dictum, arguably, they present a fuller picture of the book than the covers that have been chosen by its publishers throughout the years. As Twemlow notes in her essay, “Lolita is irresistible and frustrating to designers,”21 for many of the reasons that have been discussed already; tone is an important part of the equation. After all, how can one design a cover for “a tale that hovers between alarming depravity and slapstick?”22 Or, for that matter, how can one represent a character who remains elusive but also is, or desperately wants to be, just a normal twelve-year-old girl?

The most informed covers offer cogent and sympathetic views into Nabokov’s complex world while gingerly sidestepping egregious stereotypes, unless it’s to use them for different ends. (Remarkably, the designer of one of the most compelling covers subsequently admitted that he had in fact never read the book.) If some of the covers fall prey to the misconceptions that have plagued the published versions, the strength of the invented gallery lies in the wide range of responses. Taken as a whole, the gallery acts as a kind of barometer: a series of likely stories and hypotheses, each of which may be tested by the reader’s own criteria. No single cover stands out as definitive or can be taken as representative; rather, the images and the essays are intended to work in concert instead of providing a unified response. Ultimately, it remains for informed readers to determine how well the designs satisfy the criteria they themselves bring to the book.

1 The musical Lolita, My Love, by John Barry and Alan Jay Lerner, opened and closed in 1971. The Russian composer Rodion Shchedrin’s opera Lolita was composed in 1992 and premiered in 1994 in a Swedish-language version. Pia Pera’s novel Lo’s Diary was published in 1999. In 2009, Brian Cox portrayed Humbert Humbert in Richard Nelson’s stage adaptation.

2 Zimmer’s gallery engendered a competition of conceptual Lolita covers sponsored by the arts-and-literature blog Venus Febriculosa, and from the results of the contest emerged an essay that was published in the Nabokov Online Journal. Taken together, the gallery, contest, and essay suggested that the covers of Nabokov’s novel would be a springboard for further serious exploration.

3 Page 145 of the present book.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid., 154.

6 Ibid., 145.

7 Matthew Roth admits that he has not listened to nearly all of these tracks and that the diversity seems to be great (there are a surprising number of German-language songs). See Matthew Roth, “Lolita in Popular Music,” posting on Nabokv-L listserv (August 24, 2012).

8 Hogan, Marc. “Lana Del Rey Plays a ’Hood Lolita in ‘Off to the Races,’” December 20, 2011. <http://www.spin.com/articles/lana-del-rey-plays-hood-lolita-races>

9 Durham, M. Gigi. The Lolita Effect: The Media Sexualization of Young Girls and What We Can Do About It (New York: Overlook Press, 2008), 25; 28–29.

10 Vickers, 148.

11 Ibid., 150–151.

12 Ibid., 150.

13 Merskin, Debra. “Reviving Lolita?: A Media Literacy Examination of Sexual Portrayals of Girls in Fashion Advertising,” American Behavioral Scientist, (Vol. 48, No. 1, September 2004), 119.

14 “Lolita Show Scrapped Over Pedophilia Concerns,” Report by RIA Novosti, St. Petersburg, (October 22, 2012). <http://en.ria.ru/russia/20121022/176821446.html>

15 The Penguin Australasia sales director Peter Blake commented: “I guess there have been complaints from customers and they have reacted by removing them from sale. Retailers can do what they like.” See, Hawkins, Peter and Ellie Harvey, “Penguin Classics Prove Too Risque for Australia Post,” The Sydney Morning Herald (October 15, 2009). <http://www.smh.com.au/news/entertainment/books/penguin-classics-prove-too-risque-for-australia-post/2009/10/14/1255195830490.html>

16 Thornton, Edith. “‘Innocence’ Consumed: Packaging Edith Wharton with Kathleen Norris in Pictorial Review Magazine, 1920–21,” European Journal of American Culture (Vol. 24, No. 1, 2005), 44.

17 Page 33 of the present book.

18 Ibid., 157.

19 Ibid., 235.

20 Ibid., 234.

21 Ibid., 39

22 Ibid., 37.